Abstract

Determining the developmental consequences of activated RAS and its downstream effectors is critical to understanding several congenital conditions caused by either germline or somatic mutations of the RAS pathway. Here we demonstrate that embryonic activation of BRAF in mouse ectoderm triggers both craniofacial and skin defects, including hyperproliferation, loss of spinous and granular keratinocyte differentiation, and cleft palate. RNA-sequencing reveals that despite an apparent block in spinous and granular differentiation, the epidermis continues to mature, expressing >80% of EDC genes and forming a hydrophobic barrier, both characteristic of later stages in epidermal development. Spinous and granular differentiation can be restored by pharmacologic inhibition of MEK or BRAF; however, in tissue recombination studies, phenotypic reversion was found to be non-cell autonomous and required dermal tissue to be present. These studies indicate that early activation of the RAF signaling pathway in the ectoderm has specific effects on progressive differentiation of the epidermis, which may be amendable to treatment using existing pharmacologic inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

In addition to its well-known involvement in cancer, mutations in the RAS pathway can also be found as germline or early somatic mosaic mutations (Hafner and Groesser, 2013; Rauen, 2013). These early mutations occur in spectrum of congenital diseases, which affect internal organ, skin and hair development, several types of neoplasms and constitutional maturation. Understanding the pathogenesis and timing of these defects is critical to implementing the use of widely available RAS pathway inhibitors in the treatment of these children early in the course of disease.

The genetics of RAS/MAPK-associated diseases suggest that mutations trigger RAS paralog and effector-specific developmental and pathologic responses. HRAS mutations are far more common in Costello syndrome than KRAS mutations (95% HRAS; 5% KRAS; 0% NRAS) (Aoki et al., 2008). Mutations in BRAF and RAF1 are exclusively involved in cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Rodriguez-Viciana et al., 2006) and Noonan syndrome (RAF1) (Razzaque et al., 2007), respectively. Germline mutations in parallel RAS effector pathways, AKT/PTEN, cause yet other distinct diseases (Liaw et al., 1997; Pilarski et al., 2013). Lastly, early post-zygotic mutations also disproportionately involve specific RAS paralogs (HRAS, KRAS) and RAS effectors (AKT1) in diseases such as epidermal nevus, nevus sebaceous, Schimmelpennig, and Proteus syndromes (Groesser et al., 2012; Levinsohn et al., 2013; Lindhurst et al., 2011).

The spectrum of skin disease in RAS/MAPK syndromes suggest that the ectoderm discriminates between mutations in specific effectors and paralogs. In HRAS-associated Costello syndrome, children develop redundant skin folds and papillomas, whereas BRAF/MEK-associated disease is associated with flaky skin (ichthyosis), perifollicular hyperkeratosis (keratosis pilaris), and lack papillomas (Siegel et al., 2011; Turnpenny et al., 1992). RAF1 mutations in Noonan syndrome children trigger neither of the above cutaneous features (Roberts et al., 2006). The mechanisms that are responsible for differences in cutaneous responses to paralogs and downstream effectors of RAS are not known.

To study the effects of congenital BRAF activation of epidermal development, we used a knock-in model to activate BRAF (BrafV600E) in the ectoderm during embryogenesis. BRAF activation induces hyperplasia and interferes with progressive differentiation of the embryonic epidermis, where intermediate steps in differentiation are lost. Through RNA sequencing, in situ hybridization and barrier assay, we find that maturation of the epidermis and barrier formation continues. Inhibitors of MEK or BRAF both show efficacy in rescuing spinous and granular keratinocyte differentiation in explants of K14-cre; BrafV600E mice, demonstrating continued plasticity and responsiveness of affected epidermis. These findings reveal that congenital activation of BRAF causes specific cell identity defects in epidermal development and provides insights into the mechanisms and application of BRAF/MEK inhibition in the treatment of skin disease.

RESULTS

Congenital activation of BRAF in the embryonic ectoderm

To activate BRAF in the ectoderm, we utilized a mouse model, where expression of a mutant allele (BrafV600E) remains under the control of its endogenous locus and produces mutant product following Cre-mediated deletion of a transcription stop cassette (Dankort et al., 2007). BrafV600E floxed females were bred to Keratin 14 (K14)-cre) transgenic males, which express Cre in the epidermis at embryonic day (E) 14.5 (Vasioukhin et al., 1999). K14-cre-positive, BrafV600E-positive (K14-cre; BrafV600E) offspring were produced at near expected Mendelian frequency when assessed prior to birth (25.6% observed; 25% expected from 167 late stage embryos). Postnatally, the majority of K14-cre; BrafV600E newborns were cannibalized by adults, and at the time of weaning, only 3 K14-cre; BrafV600E mice out of > 20 litters were detected at the time of weaning. In litters observed at the moment of birth, K14-cre; BrafV600E newborns showed severe ectodermal defects, including thick, fissured scale overlying translucent edematous skin and displayed rhythmic ventilation and pink oxygenation. Further examination of K14-cre; BrafV600E newborns also revealed lack of ingested milk in their stomachs and cleft palate defects in >84% (Fig. 1b). The latter defect may result from Cre expression in the palate epithelium of K14-cre animals (Okubo et al., 2009). Histologic analysis of the skin revealed a thickened epidermis, basaloid cells, cytolysis and loss of keratohyalin granules (Fig. 1c). Although a stratified epithelium was present in K14-cre; BrafV600E mice, immunofluorescent analysis revealed loss of K10+ spinous and LOR/FLG+ granular keratinocytes (Fig. 1c). The K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis was hyperproliferative as evidenced by increased BrdU-staining and the overexpression of K6 protein.

Figure 1. Phenotype of K14-cre; BrafV600E neonatal and perinatal mice.

(a) Appearance of normal neonatal (upper row) and K14-cre; BrafV600E (bottom row) littermates. The K14-cre; BrafV600E skin appeared flaky and fissured overlying areas of translucent skin. (b) Cleft palate defects in K14-cre; BrafV600E whole mount preparations were counterstained with toluidine blue. (c) Histologic and immunofluorescent analysis of K14-cre; BrafV600E (BrafV600E) neonatal skin. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained sections demonstrate thickened epidermis, separation of individual cells, and severe reduction in cytoplasmic keratohyalin granules. Immunofluorescent staining for K10, BrdU, loricrin (LOR), filaggrin (FLG) and K6 are shown for perinatal wildtype littermate and K14-cre; BrafV600E E18.5-P0 mouse skin. Note the absence of K10pos-spinous keratinocytes and LOR/FLGpos granular keratinocytes in the K14-cre; BrafV600E mouse skin. K6, a marker for hyperproliferative skin, is increased in the K14-cre; BrafV600E mouse skin. Scale bars, 20 µm.

Congenital BRAF activation does not prevent continued differentiation

To characterize differentiation and fate of the K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, high-throughput sequencing of transcripts was performed from the E17.5 epidermis, when the skin was phenotypically abnormal but lacked extensive signs of cytolysis seen at later stages. Pooled total RNA from four control littermate and mutant E17.5 epidermis were used to generate 48.4 and 56.3 million read libraries, respectively, and unique reads were aligned to the genome and annotated (Fig. 2). 2,189 coding genes were differentially expressed in the K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, of which many participate in epidermal differentiation and keratinization (Fig. 2a). Due to the heterogeneity of epidermal tissue, gene expression data may also reflect the presence of other cell types and follicular tissues. This data was used to study the activity of genes representing specific epidermal lineages (Fig. 2b; Suppl. Fig. S1), including late steps in differentiation, which involve activation of >70 epidermal differentiation complex (EDC) genes (de Guzman Strong et al., 2010). Read coverage within the 3.3 MB interval of conserved gene cluster was analyzed and identified 63 transcriptional units, which can be categorized into five physical groups (Fig. 2c). Loss of EDC gene expression was most prominent in the LCE-like group III, where the majority of these genes were decreased by 2-fold; however, four outliers in this group representing Lce3 paralogs were upregulated (Fig. 2d). In the remaining four EDC groups, >85% (41 genes) were expressed at normal or higher levels in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis (Suppl. Fig. S2). These findings confirm that despite the loss of early and intermediate gene differentiation, the vast majority of transcriptional features of late differentiation remain active.

Figure 2. RNA-sequencing identifies the fate of epidermis in BrafV600E mutant mice and persistence of EDC gene expression.

(a) Functional classification of genes differentially expressed in E17.5 K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, demonstrating number of genes and statistical significance of their association. (b) Read coverage of wildtype vs. K14-cre; BrafV600E transcripts across the mouse Krt14 and Krt10 loci. (c) Intermediate and late differentiation genes clustered in the EDC locus and close proximity of closely related paralogs. (d) Volcano plots of relative expression of all EDC group genes from pooled wildtype vs. K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos. Specific groups of EDC genes, LCE-like (green), SPRR-like (red), and S100 family genes (blue), are colored and shown as balloons in respective cluster III, IV and V. The levels of gene expression in RNA-seq are estimated from (b) and have associated log2 q-values or FDRs (vertical axis) for this estimate. Note: this q-value does not reflect sample variance since specimens have been pooled.

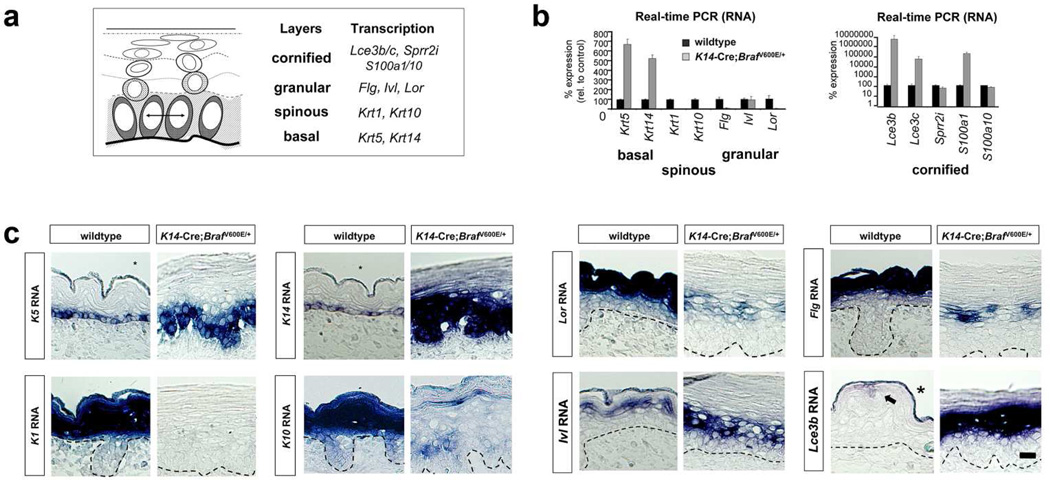

To confirm transcriptional changes identified by RNA-seq of pooled samples, real-time quantitative PCR (real-time PCR) for select differentiation markers was performed on individual embryos (Fig. 3 and Suppl. Table S1). K14-cre; BrafV600E consistently demonstrated high levels of basal lineage gene expression (K5, K14), while spinous (K1, K10) and granular (Lor, Flg) specific gene expression was markedly reduced (Fig. 3b). Late epidermal differentiation genes, Lce3b, Lce3c, S100a1, S100a10, and Sprr2i, were still expressed in the K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos and in some cases, expressed at higher levels than in wildtype littermates.

Figure 3. Expression of intermediate and late stage epidermal differentiation genes in K14-cre; BrafV600E mice.

(a) Differentiation markers used to identify basal (SB), spinous (SS), granular (SG), and cornified envelope (SC) keratinocytes. (b) Real-time PCR for gene expression at E17.5 skin reveals loss of spinous and granular differentiation markers in K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos and presence of late differentiation markers (Lce3b, Lce3c, Sprr2i, S100a1, S100a10). Error bars represent SD of four animals of each genotype. (c) E17.5 in situ hybridization of basal K5/K14, spinous K1/K10, granular Lor/Flg, involucrin (Ivl), and cornified envelope Lce3b keratinocyte gene expression. These studies show the loss of spinous and granular keratinocyte gene expression and pattern of Ivl and cornified envelope genes in upper layers. Suppl. Fig. S3 further localize gene expression by tyramide signal amplification. Scale bars, 20 µm.

To determine the pattern of differentiation in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, RNA in situ hybridization was performed (Fig. 3c). The patterns of early, intermediate, and late terminal differentiation gene expression in wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos demonstrated that late terminal differentiation gene expression remain restricted to the most distal layers. Localization of gene expression was further confirmed by tyramide-based detection, which produces a non-diffusible signal (Suppl. Fig. S3). Thus, a spatial or temporal mechanism persists in the K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis allowing for layer-specific gene expression in the upper epidermis.

Terminal steps in epidermal differentiation are critical for generating a hydrophobic barrier. This barrier becomes evident between embryonic day (E) 16.5 and 17.5 and can be detected by exclusion of water-soluble dyes, such as toludidine blue (Hardman et al., 1998). Between E14.5 to E17.5 (Suppl. Fig. S4.), K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos were more opaque than littermates at E16.5 and showed widespread hyperkeratosis at E17.5 (Suppl. Fig. S4a). Cornified sheets from K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos at E18.5 appeared to be more brittle than wildtype littermates (Suppl. Fig. S4b). Dye exclusion was visible in wildtype littermates at E16.5 as a partial (lightblue) barrier in the dorsal skin (Suppl. Fig. S4b). A similar dorsal pattern of dye exclusion was present in K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos but dye exclusion was more complete (white). By E17.5 and just prior to birth, wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos demonstrated similar barrier dye staining. Thus, in the presence of BrafV600E, the epidermis is still capable of producing a hydrophobic barrier.

Plasticity and requirements for layer identity in response to BRAF and MEK inhibition

Therapeutic inhibition of c-RAF, BRAF, and MEK1/2 is a major target of cancer drug discovery and, in rare childhood disorders, could provide potential therapies. To explore this possibility, a mouse embryonic explant system was tested in which E17.5–E18.5 skin biopsies were cultured for 24 hours in media containing inhibitors of BRAF or MEK1/2 (Fig. 4). PLX4720 is an inhibitor of BRAF and demonstrates ten-fold higher affinity for BRAFV600E than wildtype BRAF (Bollag et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2008). Paradoxically, low doses of PLX4720 (<1 µM) lead to compensatory activation of c-RAF and MEK1/2 and proliferative responses including keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinomas (Chapman et al., 2011). High doses (>10µM) of PLX4720 and other BRAF inhibitors are necessary to suppress RAF paralogs and MEK(Poulikakos et al., 2010). To assess BRAF inhibition in small amounts of explanted tissues, we assessed the levels of a downstream target gene, Dusp6, which is regulated by RAS/MAPK signaling. Dusp6 was elevated in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, and downregulated in the presence of high dose (>50µM) PLX7420 (Fig. 4a, left panel) (Bloethner et al., 2005). We next assessed the effect of BRAF inhibition on early differentiation (Fig. 4a, right panel) and found increased K1, K10, and Lor expression in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis (P=0.006) and in wildtype littermate epidermis.

Figure 4. Rescue of spinous and granular keratinocyte expression by pharmacologic inhibition of BRAF or MEK.

Wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E explants were treated with PLX4720, U0126 or vehicle for 24 hrs. (a) Real-time qPCR of Dusp6, a transcriptional target of RAS/MAPK signaling, and differentiation markers (Krt1, Krt10, Lor) in E17.5 skin after treatment with varying doses of PLX4720. (b) Real-time PCR of Dusp6, Krt 1, Krt10, and Lor gene expression in wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E skin explants with U0126. (c, d) Immunostaining of (c) K10 and K14 or (d) LOR and K14 prior to culture and after culture in vehicle, 100 µM PLX4720 or U0126. Error bars represent SD of a minimum of 3 samples for each condition. Scale bars, 20 µm.

To confirm that inhibition of BRAF and downstream effectors, MEK1/2, are responsible for the reversal of the K14-cre; BrafV600E phenotype, we also treated explants with U0126, which is a non-competitive inhibitor of MEK1 and MEK2 (Sebolt-Leopold, 2008). MEK inhibition resulted in decreased Dusp6 (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2012), and re-activation of spinous and granular layer gene expression (K1, K10, Lor) (Fig. 4b) and partial correction of other genes (Suppl. Fig. S7). These studies indicated that continuous BRAF activity via MEK activation is necessary for skin defects and that plasticity remains in the K14-cre; BrafV600E mice. To determine which layers of the epidermis respond to BRAF/MEK inhibition, we performed immunofluorescent and in situ hybridization studies on PLX4720 treated explants (Fig. 4 and not shown). PLX4720 and U0126 restored K10-positive staining of cells in layer number 2 through 4 of K14-cre; BrafV600E explants but did not activate K10 in more distal layers. In contrast, the distal layers of the wildtype epidermis express both K10 and granular layer proteins, e.g. LOR. In K14-cre; BrafV600E mice, this distal layer is however able to respond to BRAF or MEK inhibition in its expression of LOR (Fig. 4).

Plasticity in the above studies could arise from basal keratinocytes responding to BRAF/MEK inhibition or keratinocytes already residing in distal layers. To label these populations, we performed a pulse-chase labeling to follow the fate of proliferating basal keratinocytes after BRAF inhibition (Fig. 5 and Suppl. Fig. S8). BrdU was introduced in utero to pregnant females, and embryos and skin explants were isolated 2 hrs later to identify pulse-labeled cells. In K14-cre; BrafV600E explants, 47.3 ± 4.4% of basal keratinocytes vs. 29.8 ± 4.7% in wildtype basal keratinocytes were BrdU-labeled at t=2 hours (Fig. 5a). After a 24-hour chase in BrdU-free culture, we found that the majority of K10- and LOR-positive keratinocytes in PLX4720-treated explants do not arise from label-retaining keratinocytes cells. These observations suggest that PLX4720 inhibition triggers post-mitotic layers to express K10 and Lor gene expression.

Figure 5. Fate of pulse-labeled basal keratinocytes in wildtype and BrafV600E explants.

To determine the origin of spinous and granular layer revertants in wildtype and BrafV600E explants, proliferating basal keratinocytes were labeled in utero with BrdU and after embryo harvest and explant culture for 24 hrs in the presence of vehicle or PLX4720, BrdU was localized. (a) Double staining for K10 and pulse-chase BrdU demonstrate the labeling at time 0 hr and retention in post-mitotic cells 24 hrs after vehicle vs. PLX4720 treatment. (b) Double staining for loricrin and pulse-chase BrdU demonstrate lack of BrdU-labeled cells in loricrin-positive cells. In all panels, dotted lines indicate epidermal junction with dermis. Scale bars, 20 µm.

Non-cell autonomous requirements of BrafV600E-explants

The persistence of spatial patterning in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis, suggested that spinous and granular cell identities may still be present in the epidermis despite the lack of layer-specific gene expression. To demonstrate the retention or memory of spinous and granular layer identity, we tested the cell autonomy of keratinocytes in response to BRAF inhibition. Using dissociated keratinocytes from K14-cre; BrafV600E embryos, cells were treated with BRAF inhibitor for 24 hours and tested for K10 and LOR re-activation (Suppl. Fig. S5). However, under these conditions, neither K10 nor LOR expression were re-activated even though cells remain transcriptionally active. These observations suggest that re-emergence of spinous and granular layer identity in the K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermis is not a cell-autonomous process.

Because re-activation of spinous and granular keratinocyte identities appeared to be non-cell autonomous, we further tested whether surrounding tissues contribute to the epidermal response to BRAF inhibition. Previous tissue recombination studies have suggested an important role for the dermis in the histogenesis of the epidermis (Sengel, 1976). Therefore, we tested the response of epidermal sheets from wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E mouse embryos to PLX4720 after removal of the dermis (Fig. 6). Neither K10 nor LOR expression were restored by PLX4720 in K14-cre; BrafV600E epidermal sheets (Fig. 6a, b). As a control, we also tested the response of epidermal sheets after re-attached to dermis (Fig. 6a, b). Re-attachment of the epidermis to dermis restored the capacity of the epidermis to respond to BRAF inhibition and demonstrates the dermis directly or indirectly provides cues necessary for specification of spinous and granular keratinocyte identity.

Figure 6. Reversion of BrafV600E-explants is not cell autonomous, requiring a dermal signal.

(a) Schematic of preparation of explants, epidermis-only vs. epidermis with dermis reattached. (b) Spinous K10 expression in epidermis-only explants vs. epidermis re-attached to dermis from wildtype and K14-cre; BrafV600E E17.5 embryos treated with BRAF inhibitor, PLX4720. Right panels demonstrate single channel of K10 expression. (c) Granular LOR expression was examined in wildtype and BrafV600E epidermis, demonstrating the requirement for dermal reattachment for proper re-activation of LOR protein expression. Right panels demonstrate single channel of LOR expression. Scale bar, 20 µm.

Discussion

Epidermal differentiation is thought to occur in a linear manner in order to form the stratified layers of the skin. Progressive differentiation can been seen throughout other systems, including early embryongenesis, hematopoiesis, neurogenesis, T- and B-cell selection, and other tissues (Lanzavecchia and Sallusto, 2002; Morrison et al., 1997). Based on genome-wide expression profiling of the K14-cre; BrafV600E mice, we show that the skin may be more malleable than other models of progressive differentiation (Caplan and Ordahl, 1978; MacLean, 1987).

Evidence from previous studies suggests that the intermediate stages of epidermal differentiation can have alternative identities. During embryogenesis, a transient population of K10pos suprabasal keratinocytes, known as the stratum intermedium, has been shown to display continued proliferative potential (Koster and Roop, 2007; Sengel, 1976). In addition, changes in keratinocyte identity and potential have been noted after engraftment (Mannik et al., 2010). Further evidence of alternative keratinocyte identities has also been observed in the postnatal tail epidermis. Suprabasal keratinocytes can be identified in the alternating scale and interscale epidermis, which are K10neg and K10pos, respectively (Gomez et al., 2013). These examples and the results of the K14-cre; BrafV600E mouse indicate that spinous and granular keratinocyte differentiation may not be a required step in epidermal differentiation. The loss of a cell type or stage is a common dilemma in stem cell biology, where the loss of a lineage marker could signify either a change in cell identity or a more limited change, e.g. downregulation of specific markers (Spivakov and Fisher, 2007). To determine if a 'silent' spinous and granular keratinocyte cell identity is maintained in BRAF-activated keratinocytes, we tested the cell autonomy of the BRAF/MEK inhibitor response. In both assays, isolated keratinocytes and epidermal sheets, BRAF and MEK inhibition failed to rescue spinous and granular keratinocyte gene expression. The results of these studies indicate that spinous and granular keratinocyte identities are not properly maintained in the presence of activated BRAF. Whether the K14-cre; BrafV600E mice adopt an alternative intermediate epidermal identity remains to be determined.

The K14-cre; BrafV600E mouse model exhibits a model for epidermal hyperproliferation in addition to the absence of intermediate layers. The overexpression of RAF1-ER fusion protein similarly displays basal hyperproliferation and impairs epidermal differentiation (Tarutani et al., 2003). Hyperproliferation of the epidermis, however, is not always linked to a block in differentiation. For example, both overexpression of TGF-alpha or conditional activation of KrasG12D lead to hyperproliferation but do not block epidermal differentiation (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2011; Vassar and Fuchs, 1991). Thus, the inhibitory effects of RAS/MAPK signaling may be more specific to BRAF or RAF activation.

Mouse models of activated Hras, Kras, Raf1 and Braf have previously been reported. These mice surprising exhibit major differences in skin phenotypes and even lack of skin phenotypes (Chen et al., 2009; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2011; Schuhmacher et al., 2008; Tarutani et al., 2003; Urosevic et al., 2011). A previously reported BrafV600E /BrafV600E germline mutation in mouse does not lead to major epidermal differentiation defects (Urosevic et al., 2011). The knock-in targeting strategy used to generate the conditional BrafV600E allele used in our study differs from the germline BrafV600E /BrafV600E mouse model which express the mutant allele at different levels (80% of wildtype levels in the conditional BrafV600E model vs. ~30% in the germline BrafV600E /BrafV600E) (Suppl. Fig. S6). These differences in expression levels of BrafV600E likely account for differences in skin phenotypes. Neither mouse model (BrafV600E allele) completely recapitulate alleles found in human CFC; however, species differences including relative resistance of rodent models to RAS (Kakumoto et al., 2006; Muto et al., 2006) may complicate future studies.

Our findings may have medical relevance as the manipulation of the BRAF/MEK pathway could be applied to treating various epidermal disorders. In the human skin, defects during intermediate stages of epidermal differentiation are often seen. In psoriasis, loss or reduction of granular keratinocyte differentiation has been observed (Chowaniec et al., 1981). Similarly, in the wound response, spinous and granular keratinocyte markers are downregulated (Ortonne et al., 1981; Patel et al., 2006). In both settings, increased RAS/MAPK signaling has been observed (Lin et al., 1999; Sosnowski et al., 1993). Our findings support the model that RAS/MAPK signaling may be responsible some aspects of these epidermal changes; however further studies are needed to determine whether human skin conditions are responsiveness to BRAF/MEK inhibition.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies

Conditional BrafV600E (Dankort et al., 2007) and K14-cre mice (Vasioukhin et al., 1999) were maintained on a mixed genetic background, including outcrosses to Swiss Black. Intercrosses were performed using K14-cre males and floxed hemizygous BrafV600E females. Embryonic age, beginning at noon E0.5, was based on the day of post-coital plug detection. Animals were genotyped using primers in (Dankort et al., 2007). Wildtype littermates were used as controls. Expression of Braf in wildtype and BrafV600E mice are shown in Suppl. Fig. S4. All experiments were performed and approved according to the institutional guidelines established by the University of California, San Diego, Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Assays for barrier function

Embryos were collected from E15.5 to E17.5. Dye exclusion assays were performed as essentially as described (Hardman et al., 1998). Briefly, embryos were transferred through a methanol gradient and stained in 1% toluidine blue for 10 minutes and destained. To isolate cornified sheets, frozen embryonic skin was thawed and treated with Dispase II (Roche) for 1 hr at 37C, trypsinized, washed and isolated. Darkfield images of cornified sheets were observed with Olympus MVX10 stereomicroscope.

Tissue collection, storage, and RNA extraction

Tissue for immunostaining and histology were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C or flash frozen in OCT. Isolated epidermal sheet were obtained from embryonic skins incubated with Dispase II (Roche) and separated from the underlying dermis. RNA was extracted from epidermal sheets that were placed in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and disrupted with 1 mm zirconia beads (BioSpec Products). Prior to use, RNA was treated RNase-free DNase and further concentrated using a RNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research).

Histology, immunofluorescence, in situ hybridization

For immunofluorescent staining, the primary and secondary antibodies used in this study are described in Supplemental Methods. In situ hybridizations were performed essentially as described (Etchevers et al., 2001). Riboprobes were generated using T7 or SP6-modified oligos (Suppl. Table S1) and amplified by PCR.

RNA analysis by real-time PCR and high throughput sequencing

Primer sequences are detailed in Suppl. Table S3 using Primer3 (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000), and real-time qPCR performed with Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis and SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Kits (Thermo Fermentas) in triplicate on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche). A comparative CT method was used for analysis using Gapdh or Beta-actin for mouse mRNAs (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

For RNA sequencing, total RNA was pooled from four wildtype and mutant E17.5 epidermal sheets. NuGEN Ovation RNASeq v1 was used to generate cDNA, fragment, end repair and polyA-tail following the TruSeq (Illumina) protocol. Raw data was processed using BOWTIE, FASTX-Toolkit and aligned to the mouse genome (mm9) (Trapnell et al., 2009). For assembly and quantification, Cufflinks (Trapnell et al., 2012) was used and differentially expressed genes identified by Cufflinks were expressed as log2-fold changes of mean FPKM of mutant and wildtype RNAs. Benjamini-Hochberg corrected q-values were reported in volcano plots. RNAseq data will be accessioned at NCBI SRA Archive, SUB373241.

Explant assay and drug treatment

Explant cultures were performed as previously described with small modifications (Halprin et al., 1979). In brief, embryonic skin was isolated, cut into 4×2 mm strips, placed on gelatin-coated 10µm Isopore membrane filter (Millipore), and floated over DMEM, 10% FCS (Invitrogen) with antibiotics at 37°C for 0 to 24 hours, 7% CO2. Explants were treated with vehicle, U0126 (Promega), or PLX4720 (EMD Chemicals) solubilized in DMSO (<0.2% final). RNA was isolated from samples as described above except that whole skin was used, and immunostained sections were obtained from fixed explant tissue. For pulse-chase studies, 50Kg BrdU/g was injected intraperitoneally in pregnant mice 2 hours prior to isolation of embryos. Explants were fixed×1 hr, blocked in OCT and 8 µm sections were cut, rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of ethanol, denatured in 4N HCl, neutralized, trypsinized and inactivated. The tissues were stained with anti-BrdU (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich) with secondary detection using MOM kit (Vector labs) and Strepavidin-Alexa 488 (Life Technologies).

Epidermal sheets prepared from Dispase II (Roche)-treated embryonic skin. For dissociation, epidermal sheets were further treated with Accutase (Chemicon/Millipore), inactivated, and placed in the same media and growth conditions as described above. Viability of epidermal sheets and keratinocytes were validated by the presence of active transcription assessed at the end of 24 hour culture with 2 hr actinomycin treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. McMahon, D. Dankort, and C. Jamora for generously sharing animals carrying the conditional BrafV600E allele and K14-cre; C. Jamora and R. Gallo lab for contributing reagents and helpful discussions. We thank that UCSD Skin Genomics Core for RNA-seq analysis. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number AR056667, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine RN2-00908, Joseph A. Stirrup Skin Cancer Foundation, R. Hotto Transdermal Research and institutional funds for B.D.Y. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other supporters.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflicts of interest.

References Cited

- Aoki Y, Niihori T, Narumi Y, et al. The RAS/MAPK syndromes: novel roles of the RAS pathway in human genetic disorders. Human Mutation. 2008;29:992–1006. doi: 10.1002/humu.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloethner S, Chen B, Hemminki K, et al. Effect of common B-RAF and N-RAS mutations on global gene expression in melanoma cell lines. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1224–1232. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, et al. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Ordahl CP. Irreversible gene repression model for control of development. Science. 1978;201:120–130. doi: 10.1126/science.351805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Mitsutake N, LaPerle K, et al. Endogenous expression of Hras(G12V) induces developmental defects and neoplasms with copy number imbalances of the oncogene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:7979–7984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900343106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowaniec O, Jablonska S, Beutner EH, et al. Earliest clinical and histological changes in psoriasis. Dermatologica. 1981;163:42–51. doi: 10.1159/000250139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankort D, Filenova E, Collado M, et al. A new mouse model to explore the initiation, progression, and therapy of BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors. Genes & development. 2007;21:379–384. doi: 10.1101/gad.1516407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman Strong C, Conlan S, Deming CB, et al. A milieu of regulatory elements in the epidermal differentiation complex syntenic block: implications for atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19:1453–1460. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchevers HC, Vincent C, Le Douarin NM, et al. The cephalic neural crest provides pericytes and smooth muscle cells to all blood vessels of the face and forebrain. Development (Cambridge, England) 2001;128:1059–1068. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez C, Chua W, Miremadi A, et al. The Interfollicular Epidermis of Adult Mouse Tail Comprises Two Distinct Cell Lineages that Are Differentially Regulated by Wnt, Edaradd, and Lrig1. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groesser L, Herschberger E, Ruetten A, et al. Postzygotic HRAS and KRAS mutations cause nevus sebaceous and Schimmelpenning syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44:783–787. doi: 10.1038/ng.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner C, Groesser L. Mosaic RASopathies. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:43–50. doi: 10.4161/cc.23108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halprin KM, Lueder M, Fusenig NE. Growth and differentiation of postembryonic mouse epidermal cells in explant cultures. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;72:88–98. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12530303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardman MJ, Sisi P, Banbury DN, et al. Patterned acquisition of skin barrier function during development. Development (Cambridge, England) 1998;125:1541–1552. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.8.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakumoto K, Sasai K, Sukezane T, et al. FRA1 is a determinant for the difference in RAS-induced transformation between human and rat fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5490–5495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601222103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster MI, Roop DR. Mechanisms regulating epithelial stratification. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2007;23:93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Progressive differentiation and selection of the fittest in the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:982–987. doi: 10.1038/nri959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinsohn JL, Tian LC, Boyden LM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals somatic mutations in HRAS and KRAS, which cause nevus sebaceus. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:827–830. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw D, Marsh DJ, Li J, et al. Germline mutations of the PTEN gene in Cowden disease, an inherited breast and thyroid cancer syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;16:64–67. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin P, Baldassare JJ, Voorhees JJ, et al. Increased activation of Ras in psoriatic lesions. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol. 1999;12:90–97. doi: 10.1159/000029850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhurst MJ, Sapp JC, Teer JK, et al. A mosaic activating mutation in AKT1 associated with the Proteus syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:611–619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean NaH, B K. Cell commitment and differentiation. Cambridge: University Press; 1987. p. 247. [Google Scholar]

- Mannik J, Alzayady K, Ghazizadeh S. Regeneration of multilineage skin epithelia by differentiated keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:388–397. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Shah NM, Anderson DJ. Regulatory mechanisms in stem cell biology. Cell. 1997;88:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81867-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Krishnaswami SR, Cowing-Zitron C, et al. Negative regulation of Shh levels by Kras and Fgfr2 during hair follicle development. Dev Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Krishnaswami SR, Yu BD. Activated Kras alters epidermal homeostasis of mouse skin, resulting in redundant skin and defective hair cycling. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:311–319. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto S, Katsuki M, Horie S. Rapid induction of skin tumors in human but not mouse c- Ha-ras proto-oncogene transgenic mice by chemical carcinogenesis. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:842–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo T, Clark C, Hogan BL. Cell lineage mapping of taste bud cells and keratinocytes in the mouse tongue and soft palate. Stem Cells. 2009;27:442–450. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortonne JP, Loning T, Schmitt D, et al. Immunomorphological and ultrastructural aspects of keratinocyte migration in epidermal wound healing. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1981;392:217–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00430822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel GK, Wilson CH, Harding KG, et al. Numerous keratinocyte subtypes involved in wound re-epithelialization. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:497–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, et al. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, et al. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauen KA. The RASopathies. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2013;14:355–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaque MA, Nishizawa T, Komoike Y, et al. Germline gain-of-function mutations in RAF1 cause Noonan syndrome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/ng2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 2006;43:833–842. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.042796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science (New York, NY. 2006;311:1287–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1124642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmacher AJ, Guerra C, Sauzeau V, et al. A mouse model for Costello syndrome reveals an Ang II-mediated hypertensive condition. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:2169–2179. doi: 10.1172/JCI34385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebolt-Leopold JS. Advances in the development of cancer therapeutics directed against the RAS-mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3651–3656. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengel P. Morphogenesis of Skin. UK: Cambridge University Press; 1976. p. 277. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowski RG, Feldman S, Feramisco JR. Interference with endogenous ras function inhibits cellular responses to wounding. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:113–119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spivakov M, Fisher AG. Epigenetic signatures of stem-cell identity. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:263–271. doi: 10.1038/nrg2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarutani M, Cai T, Dajee M, et al. Inducible activation of Ras and Raf in adult epidermis. Cancer research. 2003;63:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, et al. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3041–3046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711741105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnpenny PD, Dean JC, Auchterlonie IA, et al. Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome with new ectodermal manifestations. Journal of medical genetics. 1992;29:428–429. doi: 10.1136/jmg.29.6.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urosevic J, Sauzeau V, Soto-Montenegro ML, et al. Constitutive activation of B-Raf in the mouse germ line provides a model for human cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5015–5020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016933108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Wise B, et al. The magical touch: genome targeting in epidermal stem cells induced by tamoxifen application to mouse skin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:8551–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R, Fuchs E. Transgenic mice provide new insights into the role of TGF-alpha during epidermal development and differentiation. Genes Dev. 1991;5:714–727. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.