Abstract

Objectives. We examined smoking cessation rate by education and determined how much of the difference can be attributed to the rate of quit attempts and how much to the success of these attempts.

Methods. We analyzed data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS, 1991–2010) and the Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS, 1992–2011). Smokers (≥ 25 years) were divided into lower- and higher-education groups (≤ 12 years and > 12 years).

Results. A significant difference in cessation rate between the lower- and the higher-education groups persisted over the last 2 decades. On average, the annual cessation rate for the former was about two thirds that of the latter (3.5% vs 5.2%; P < .001, for both NHIS and TUS-CPS). About half the difference in cessation rate can be attributed to the difference in quit attempt rate and half to the difference in success rate.

Conclusions. Smokers in the lower-education group have consistently lagged behind their higher-education counterparts in quitting. In addition to the usual concern about improving their success in quitting, tobacco control programs need to find ways to increase quit attempts in this group.

It is well established that smoking prevalence is much higher among those with lower education than among those with higher education.1–6 However, the literature on the difference in cessation rate by education level is inconsistent.7,8 Given that the smoking prevalence of any group is determined by the rate at which nonsmokers take up cigarettes and current smokers quit smoking, it is important to understand if the disparity in smoking prevalence comes from uptake or cessation or both.9 This study examined cessation.

Some studies have reported that smokers with less education find it more difficult to quit smoking.4,10–13 It has also been suggested that the disparity in cessation rate by education has increased over time.4 Other studies, however, have suggested that the smoking cessation rates are not significantly different between education groups.8,14–18 These studies suggest that once people have become established smokers, they find it equally difficult to quit regardless of education level. One study even reported the reverse association between education and cessation; smokers with less education were more successful at quitting than were those with more education.19

The inconsistency in these reports may stem partly from the use of different samples. Some studies were based on clinical samples13,20,21 and others on population surveys.11,14,15 Some had larger samples,10,16 and others had relatively small samples.4,17 In addition, some studies adjusted for covariates such as family or personal income11,19 and motivation14,15 in their analysis, whereas others did not.13,17 These adjustments may help researchers understand what factors are correlated with education level, but they divert attention from the simpler question of whether a difference in the cessation rate is seen between education groups. In short, heterogeneity in study samples and analytical approaches contributed to inconsistencies in reports of whether cessation rates differed between groups with different levels of education.

This study attempted to resolve this issue by analyzing data from 2 US nationally representative surveys with very large samples collected over 2 decades. The strength of large, nationally representative samples is the ability to provide statistically reliable estimates. Also, the long period of study allowed us to check for trends in the difference between education groups over time. We used 2 national surveys to determine whether the difference found in 1 survey can be replicated in the other. In addition, we separately examined the quit attempt rates and success rates of those quit attempts. We further quantified the difference in cessation rates, if any, by partitioning the difference into the difference in the rate of making quit attempts and the difference in the success of these quit attempts.

METHODS

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is an ongoing survey of a nationally representative sample of the noninstitutionalized US population. The survey has assessed smoking cessation annually since 1991 (except 1993 and 1996); we used data from 1991 to 2010. A detailed description of the survey methodology can be found on the NHIS Web site.22

The Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS) is another nationally representative survey of tobacco use, administered by the US Census Bureau. The TUS has been conducted periodically as part of the CPS for the years 1992 to 1993, 1995 to 1996, 1998 to 1999, 2001 to 2002, 2003, 2006 to 2007, and 2010 to 2011. The TUS-CPS collects more information on smoking cessation than does the NHIS. Details about the sampling design can be found on the TUS-CPS Web site.23

This study included self-respondents (no proxies) aged 25 years and older. The age restriction was used to avoid bias among young age groups who may not have had sufficient time to complete their intended education. The average sample size for the surveys used in this study was 5669 from NHIS and 34156 from TUS-CPS.

Measures

For both NHIS (1991–2010) and TUS-CPS (1992–2011), ever smokers were defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. We focused on annual cessation rate, which was defined as the percentage of those who were smokers 12 months prior to the survey who, at the time of survey, had quit smoking for at least 3 months.

For TUS-CPS (2001–2011), the quit attempt rate was calculated as the percentage of those who were smokers 12 months prior who made any quit attempt that lasted at least 24 hours in the previous 12 months. The success rate of these quit attempts was estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Six-month Kaplan–Meier survival curves were plotted for those quit attempts. This analysis included quit attempts made by both current and former smokers at the time of survey. For current smokers, their self-reported longest length of quit was included. For former smokers, their length of quit was censored because they were not smoking at the time of survey.

The smoking and quitting measures for this study were all based on self-report. This is a limitation because it might involve biases, although self-report of smoking behavior generally has been shown to be accurate for population surveys when compared with biochemical data.24

To simplify the analysis on disparity, we divided respondents into 2 groups: lower education (≤ 12 years) and higher education (> 12 years). We adopted this dichotomy after preliminary analyses that used more educational categories showed that the cessation rate of those who completed 12 years of education was much lower than the rate of those who had some postsecondary education.

Analysis

To avoid potential confounding as a result of the changing ethnic composition of the United States over the last 20 years, all analyses were performed twice: once using all smokers and then separately for non-Hispanic White smokers. By contrast, age was not controlled for in the analysis. Age is usually an important variable to consider because older ever smokers have more time to quit smoking and thus are more likely to have quit smoking compared with younger ever smokers, as in the case when calculating the quit ratio.1,9 However, this study analyzed annual cessation rates, not quit ratios. The quit ratio refers to the accumulated quit rate among ever smokers, which would lead to older smokers having a higher quit ratio. Annual cessation rates do not use all ever smokers in the denominator—instead, the denominators include only those who were smokers 12 months prior to each survey. Because only those ever smokers who were still smoking 12 months prior to the survey were included in the analysis, the effect of age was minimized.25 We analyzed the trend of annual cessation rates across several age groups. After confirming no difference in trend, we decided not to present the data by age groups to keep the Results section manageable.

For each of the 18 NHIS surveys and the 7 TUS-CPS surveys, we estimated the overall cessation rate by education and computed the difference between education groups. To adjust for multiple comparisons (retaining an overall 95% family-wise error rate), we computed confidence intervals (CIs) at 99.72% for NHIS (18 tests) and 99.27% for TUS-CPS (7 tests).26 Furthermore, we constructed a confidence band by computing CIs for the estimated regression curve of differences in the cessation rate at each survey year with locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing.26,27

The relevant data to compute the quit attempt rate and the survival curves separately were available from only TUS-CPS (2001–2011). From 2001 to 2011, all TUS-CPS surveys assessed the duration of the longest quit attempt, which could lead to overestimating the success rate of quit attempts. The 2003 and 2010 to 2011 surveys also assessed for the duration of the most recent quit attempt. The data from these years provided an opportunity to study differences between the 2 measures. We found that the shape of the relapse curves was similar with either measure, although the abstinence rate at the earlier stage tended to be higher when using the longest quit attempt. Because the longest quit attempt was assessed in all years, we used the longest quit attempt data to combine data from all years. Any overestimation for the earlier stage of quitting was assumed to occur at similar levels for both education groups.

The cessation rate in each education group is the product of the attempt and success rates for that group. This implies that the ratio of cessation rates in the 2 groups, which we call the cessation ratio,

|

can be computed as a product of attempt and success ratios. Here, C is the cessation rate, A is the quit attempt rate, S is the success rate, and the subscripts l and h correspond to the low- and high-education groups, respectively. To assess how much of the cessation ratio is caused by differences in the quit attempt rates versus differences in the success rates between the 2 groups, we calculated that proportion of the ratio that is a result of quit attempts  versus successes

versus successes  . The sum of these ratios is always 1, and they reflect the relative contribution of differences in attempt and success rates in determining the difference in cessation rates, all expressed as ratios.

. The sum of these ratios is always 1, and they reflect the relative contribution of differences in attempt and success rates in determining the difference in cessation rates, all expressed as ratios.

All analyses were weighted to adjust for the unequal probability of selection. The weights were adjusted to sum to the observed sample size for each of the survey years, when the data from 1991 to 2011 or from 2001 to 2011 were combined in the same analysis. Variance estimates were computed using SUDAAN 11.0 statistical software.28 Locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing analysis was conducted with R 3.0.1.29

RESULTS

Figure 1 presents NHIS data from 1991 to 2010. The annual cessation rates by education for all smokers and non-Hispanic White smokers were very similar throughout the 20-year period. The cessation rates among lower-educated smokers were consistently lower than among higher-educated smokers, although the differences in some years did not reach statistical significance.

FIGURE 1—

Smoking cessation rates by education groups among (a) all smokers from the NHIS, (b) all smokers from the TUS-CPS, (c) non-Hispanic Whites from the NHIS, and (d) non-Hispanic Whites from the TUS-CPS: NHIS, 1991–2010, and TUS-CPS, 1992–2011.

Note. high = high education; low = low education; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; TUS-CPS = Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey. The confidence intervals are 95%, pointwise. The denominator for each cessation rate is the number of current and recent former smokers, and the numerator is the number of recent former smokers who have quit for 3 months. The 1992 NHIS data were adjusted to account for missing data caused by a skip pattern error in survey implementation.

Figure 1 also presents data from TUS-CPS. Estimates have smaller SEs than do those for NHIS because of a larger sample size. Thus, the differences in cessation rate between lower- and higher-education groups in each survey year were all statistically significant among all smokers and non-Hispanic White smokers.

The average cessation rates across the total study period were very similar for these 2 surveys. For NHIS, the average cessation rates for all smokers for the period from 1991 to 2010 were 3.5% (95% CI = 3.2%, 3.8%) and 5.2% (95% CI = 4.8%, 5.5%) for the low- and high-education groups, respectively. For TUS-CPS, the average cessation rates for the period from 1992 to 2011 were 3.5% (95% CI = 3.1%, 3.8%) and 5.2% (95% CI = 4.7%, 5.6%) for low- and high-education groups, respectively. A similar pattern was found in the analysis of non-Hispanic White participants. In the NHIS, the average cessation rates were 3.6% (95% CI = 3.3%, 3.9%) and 5.4% (95% CI = 5.0%, 5.7%) for low- and high-education groups, respectively; and in the TUS-CPS, the rates were 3.6% (95% CI = 3.2%, 4.0%) and 5.3% (95% CI = 4.8%, 5.7%), respectively.

Figure 2 displays the data from Figure 1 in a different way, to check whether the difference between the 2 education groups has grown over time. The difference in the cessation rate between the 2 groups has not changed significantly over time: the 95% confidence bands for the difference in cessation rate include the mean rates over the years, whether the analysis included all smokers or only non-Hispanic White smokers. This is true for both NHIS and TUS-CPS. The picture is even clearer for the latter because its larger sample sizes render the curves more stable.

FIGURE 2—

Difference in annual smoking cessation rates by education groups among (a) all smokers from the NHIS, (b) all smokers from the TUS-CPS, (c) non-Hispanic Whites from the NHIS, and (d) non-Hispanic Whites from the TUS-CPS: NHIS, 1991–2010, and TUS-CPS, 1992–2011.

Note. NHIS = National Health Interview Survey; TUS-CPS = Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey. The smoothed confidence band is shown in light gray, the estimated trend in solid line, and the overall mean in dashed line. To reach an overall 95% confidence level, estimates in each year were adjusted to the level of 99.72% in the NHIS and 99.27% in the TUS-CPS.

To address how much of the difference in the cessation rate comes from the quit attempt rate and how much comes from the successful quit rate, we examined the TUS-CPS data from 2001 to 2011. We did not analyze NHIS data because the surveys did not assess the relapse rate directly. Table 1 shows the quit attempt rates by education among all smokers and non-Hispanic White smokers. The quit attempt rate varied between the years. However, the difference between education groups was similar across the years and was statistically significant in each year. On average, the quit attempt rate among all smokers was 35.6% for lower-educated smokers and 42.9% for higher-educated smokers. In the analysis focused on the non-Hispanic White smokers only, the mean quit attempt rates were 33.9% and 41.7% for lower- and higher-educated smokers, respectively. The difference was statistically significant. Thus, the quit attempt rate for the lower-educated smokers was 82.9% of that of higher-educated smokers. In the analysis focused on non-Hispanic White smokers only, it was 81.3%.

TABLE 1—

Difference in Percentage of Smokers Making a Quit Attempt by Education Groups Among All Smokers and Non-Hispanic White Smokers: Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS), United States, 2001–2011

| All Smokers |

Non-Hispanic White Smokers |

|||||

| Year | No. | Low Education, % (95% CI) | High Education, (95% CI) | No. | Low Education, % (95% CI) | High Education, % (95% CI) |

| 2001–2002 | 34 159 | 34.5 (33.7, 35.2) | 43.1 (42.1, 44.0) | 27 838 | 32.6 (31.7, 33.5) | 42.0 (40.9, 43.1) |

| 2003 | 30 074 | 35.8 (34.8, 36.8) | 42.6 (41.5, 43.8) | 24 147 | 34.4 (33.3, 35.6) | 41.3 (40.1, 42.6) |

| 2006–2007 | 28 095 | 35.0 (34.0, 36.1) | 42.5 (41.4, 43.6) | 22 611 | 33.2 (32.1, 34.2) | 41.1 (39.9, 42.2) |

| 2010–2011 | 24 638 | 37.7 (36.7, 38.7) | 43.6 (42.4, 44.9) | 19 227 | 36.2 (35.1, 37.3) | 42.7 (41.3, 44.1) |

| Mean | 35.6 (34.3, 36.9) | 42.9 (41.5, 44.4) | 33.9 (32.5, 35.4) | 41.7 (40.0, 43.4) | ||

Note. CI = confidence interval. The denominator for the quit attempt rate is the number of current and recent former smokers; the numerator is the number of current smokers who made a quit attempt and number of recent former smokers.

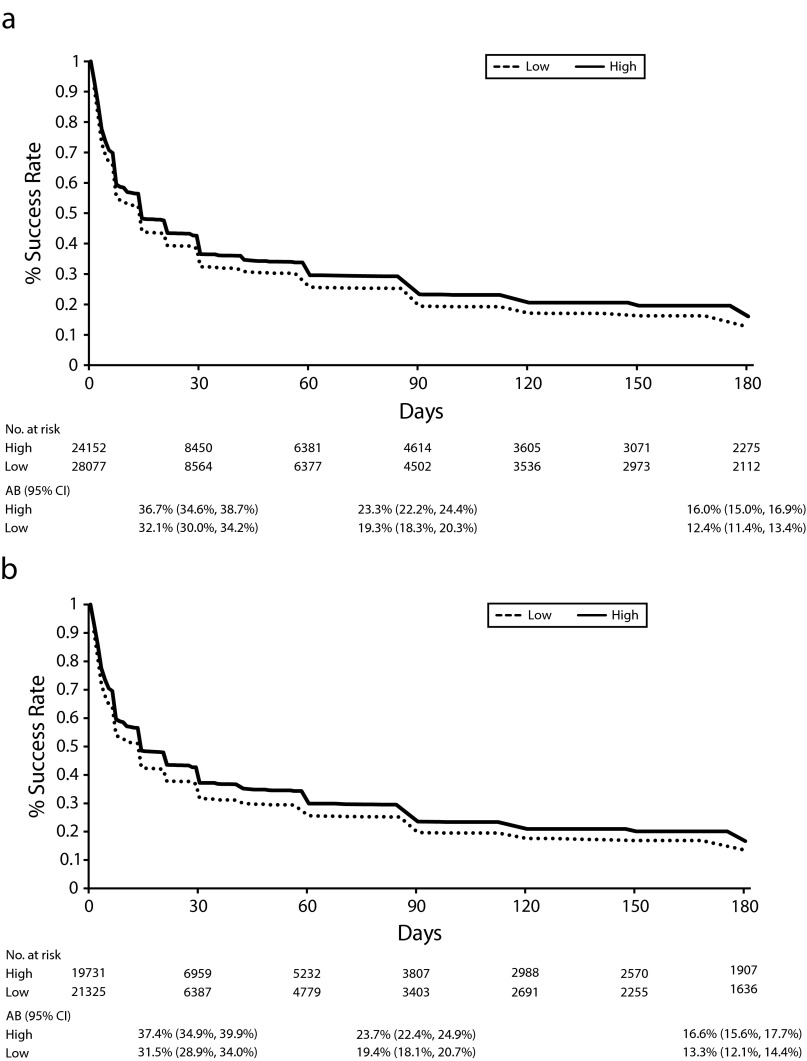

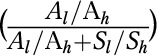

Figure 3 shows the relapse curves for smokers who made quit attempts in the previous 12 months from 2001 to 2011. These curves show that more than half of smokers failed in their quit attempts within 1 month. This is true for both the lower- and the higher-education groups, although lower-educated smokers were more likely to relapse than higher-educated smokers. The average 3-month success rate was 19.3% (95% CI = 18.3%, 20.3%) for lower-educated smokers and 23.3% (95% CI = 22.2%, 24.4%) for higher-educated smokers among all smokers. In the analysis focused on non-Hispanic White smokers only, the average 3-month success rate was 19.4% (95% CI = 18.1%, 20.7%) and 23.7% (95% CI = 22.4%, 24.9%) for lower- and higher-educated smokers, respectively. The differences in the success rates between education groups were all statistically significant (P < .001). For all smokers, the 3-month success rate from a given attempt among the lower-education group was 82.7% of that among higher-educated smokers. In the analysis focused on only non-Hispanic White smokers, it was 82.0%.

FIGURE 3—

Success rate of given quit attempts by education groups among (a) all smokers and (b) non-Hispanic Whites: Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey, United States, 2001–2011.

Note. AB = percentage abstinent; CI = confidence interval; high = high education; low = low education.

The cessation ratio between the 2 education groups was calculated with Equation 1 (Methods section). The cessation rate among lower-educated smokers was 68.5% (82.9% × 82.7%) that of higher-educated smokers from the TUS-CPS (2001–2011; 66.7% [81.3% × 82.0%] for non-Hispanic White smokers). Furthermore, the cessation ratio was partitioned into 2 components: quit attempt rate and success rate. For all smokers, 50.1% (82.9%/[82.9%+82.7%]) of the educational difference ratio in the cessation rate came from the quit attempt rate, and 49.9% (82.7%/[82.9%+82.7%]) came from the success rate. For non-Hispanic White smokers, 49.8% (81.3%/[81.3%+82.0%]) and 50.2% (82.0%/[81.3%+82.0%]) of the difference in cessation rate came from the quit attempt and success rates, respectively.

With the more stringent criterion of 6-month success, 51.7% (82.9%/[82.9%+77.6%]) and 48.3% (77.6%/[82.9%+77.6%]) of the cessation ratio came from the quit attempt and success rates, respectively, among all smokers. Among non-Hispanic White smokers, 50.5% (81.3%/[81.3%+79.8%]) and 49.5% (79.8%/[81.3%+79.8%]) of the difference in the cessation rate came from the quit attempt and success rates, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study, based on 2 large national surveys over 2 decades, found that smokers with less education had lower cessation rates than did smokers with more education, and this disparity persisted over the whole study period. The magnitude of disparity, about one third, was substantial. However, it has not increased in the last 2 decades.

This study had several methodological strengths. First, it provided population estimates of cessation rate difference by education groups from population surveys instead of clinical samples. Second, the sample size was very large. The combined sample was more than 340 000 smokers. Third, the study examined the population difference over an extended period and found that the difference persisted. In fact, the 2 decades under consideration was a period in which many smoking cessation interventions were developed and implemented,25 and yet the difference remained. Finally, the results found in 1 national survey were verified with another national survey. In fact, the second survey provided almost a perfect confirmation of the findings, both in pattern and in magnitude of difference. This study, therefore, provided conclusive evidence that a significant difference in cessation rate existed and persisted between the 2 education groups in the United States. From a methodological perspective, such a study provides a more definitive answer to the question of whether there is a difference between the 2 groups than if we had attempted to use meta-analysis to synthesize the results from different studies with heterogeneous designs.30

The current study, however, does not explain why there is such a difference. It went only so far as to quantify 2 aspects of quitting. Approximately half of the difference between the 2 groups was a result of the fact that smokers in the low-education group were less likely to make a quit attempt in any given 12-month period. The other half of the difference came from the fact that they were less likely to succeed in quitting after they made a quit attempt.

Whether the reasons for the lower quit attempt rate and the lower success rate are the same is not clear. One possible explanation is that the persistent difference in cessation rate between the groups reflects the marked difference in smoking prevalence between the groups. Smokers with lower education are more likely to live in neighborhoods or homes where tobacco is more accessible and acceptable compared with smokers with higher education.31–33 As a result, they are more likely to be surrounded by family, friends, or coworkers who smoke and more likely to perceive smoking as normative.34 This affects their likelihood of making attempts to quit smoking. Even if they attempt to quit, they are more likely to relapse because of the greater exposure to smoking cues.35,36

Another possible explanation for the persistent difference in cessation rate between the groups is that smokers with lower education tend to have fewer financial and psychological resources to support them in their efforts to quit smoking compared with those with higher education.37,38 For example, although all smokers have access to free cessation services such as a quitline,39 smokers with lower education are less likely to spend money on effective cessation aids.40 Additionally, even when lower-educated smokers want to quit smoking, they may be less likely to have sufficient psychological resources (e.g., self-efficacy) to do so.41,42 This may diminish their number of quit attempts and limit their capability to reduce their stress or anxiety and cope with withdrawal symptoms.43,44

Whatever the explanation may be, the fact that the difference in cessation rate between education groups has not changed over the past 2 decades suggests that the gap is intrinsically difficult to narrow. This is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future unless smoking norms among those with a lower level of education shift or significant resources are made available to support quitting among those with low education levels. Nevertheless, the finding that the quit attempt rate and the success rate contribute equally to the group difference in cessation suggests that future interventions could approach these problems either by promoting quit attempts among smokers with a lower level of education or by improving the success rate of their quit attempts. The smoking cessation field tends to emphasize the need to provide cessation service to prevent relapse because the relapse rate is so high. However, most quit attempts on the population level are unaided, even with the increasing availability of cessation aids in the last 20 years.25,45 Moreover, this emphasis on relapse prevention is often done at the expense of neglecting the other obvious fact that many smokers do not even make a quit attempt.25,46,47 For example, this study showed that more than 60% of the smokers in the low-education group did not make a serious quit attempt in any given 12-month period. Given that boosting quit attempt rates often has been neglected in the cessation field,25 future interventions aiming to improve the cessation rate of the low-education group may do well to place more emphasis on increasing the quit attempt rate.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the State and Community Tobacco Control Initiative (award U01CA154280); University of California, San Diego (principal investigator: S.-H. Z.).

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

Approval for this study was granted by the institutional review board at the University of California, San Diego (IRB protocol 140821).

References

- 1.Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Hatziandreu EJ, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States: educational differences are increasing. JAMA. 1989;261(1):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escobedo LG, Peddicord JP. Smoking prevalence in US birth cohorts: the influence of gender and education. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(2):231–236. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iribarren C, Luepker RV, McGovern PG, Arnett DK, Blackburn H. Twelve-year trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Minnesota Heart Survey: are socioeconomic differences widening? Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):873–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: initiation, regular use, and cessation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(10):802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanjilal S, Gregg EW, Cheng YJ et al. Socioeconomic status and trends in disparities in 4 major risk factors for cardiovascular disease among US adults, 1971–2002. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2348–2355. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu SH, Hebert K, Wong S, Cummins S, Gamst A. Disparity in smoking prevalence by education: can we reduce it? Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1 suppl):29–39. doi: 10.1177/1757975909358361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaap MM, Kunst AE. Monitoring of socio-economic inequalities in smoking: learning from the experiences of recent scientific studies. Public Health. 2009;123(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maralani V. Educational inequalities in smoking: the role of initiation versus quitting. Soc Sci Med. 2013;84:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns DM, Anderson CM, Johnson M . Population-Based Smoking Cessation: Proceedings of a Conference on What Works to Influence Smoking in the General Population. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2000. Cessation and cessation measures among adult daily smokers: national and state-specific data. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph, No. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillard DR, Plassmann V, Kenkel D, Mathios A. Who kicks the habit and how they do it: socioeconomic differences across methods of quitting smoking in the USA. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2504–2519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid JL, Hammond D, Boudreau C, Fong GT, Siahpush M. ITC Collaboration. Socioeconomic disparities in quit intentions, quit attempts, and smoking abstinence among smokers in four western countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(suppl):S20–S33. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wetter DW, Cofta-Gunn L, Irvin JE et al. What accounts for the association of education and smoking cessation? Prev Med. 2005;40(4):452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviours among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 3):iii83–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009;34(4):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6(suppl 2):S57–S62. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellman R, Cummings KM, Haughey BP, Zielezny MA, O’Shea RM. Predictors of attempting and succeeding at smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 1991;6(1):77–86. doi: 10.1093/her/6.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McWhorter WP, Boyd GM, Mattson ME. Predictors of quitting smoking: the NHANES I followup experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(12):1399–1405. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rafful C, García-Rodríguez O, Wang S, Secades-Villa R, Martínez-Ortega JM, Blanco C. Predictors of quit attempts and successful quit attempts in a nationally representative sample of smokers. Addict Behav. 2013;38(4):1920–1923. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey SR, Bryson SW, Killen JD. Predicting successful 24-hr quit attempt in a smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(11):1092–1097. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caponnetto P, Polosa R. Common predictors of smoking cessation in clinical practice. Respir Med. 2008;102(8):1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the National Health Interview Survey. June 13, 2012. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 23.Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey: What is the TUS-CPS? January 13, 2014. Available at: http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/studies/tus-cps. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 24.Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(7):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu SH, Lee M, Zhuang YL, Gamst A, Wolfson T. Interventions to increase smoking cessation at the population level: how much progress has been made in the last two decades? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):110–118. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardle W. Applied Nonparametric Regression: Econometric Society Monographs. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleveland WS, Devlin SJ. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(403):596–610. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 11. Vol. 1 and 2. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2012.

- 29.An introduction to R. March 6, 2014. Available at: http://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/R-intro.html. Accessed March 25, 2014.

- 30.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahern J, Galea S, Hubbard A, Syme SL. Neighborhood smoking norms modify the relation between collective efficacy and smoking behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100(1-2):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chuang YC, Cubbin C, Ahn D, Winkleby MA. Effects of neighbourhood socioeconomic status and convenience store concentration on individual level smoking. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(7):568–573. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stimpson JP, Ju H, Raji MA, Eschbach K. Neighborhood deprivation and health risk behaviors in NHANES III. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(2):215–222. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(21):2249–2258. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiffman S, Paty JA, Gnys M, Kassel JA, Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(2):366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen PH, White HR, Pandina RJ. Predictors of smoking cessation from adolescence into young adulthood. Addict Behav. 2001;26(4):517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aneshensel CS. Toward explaining mental health disparities. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(4):377–394. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honjo K, Tsutsumi A, Kawachi I, Kawakami N. What accounts for the relationship between social class and smoking cessation? Results of a path analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(2):317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu SH, Gardiner P, Cummins S et al. Quitline utilization rates of African-American and White smokers: the California experience. Am J Health Promot. 2011;25(5 suppl):S51–S58. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100611-QUAN-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorndike AN, Biener L, Rigotti NA. Effect on smoking cessation of switching nicotine replacement therapy to over-the-counter status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):437–442. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiviruusu O, Huurre T, Haukkala A, Aro H. Changes in psychological resources moderate the effect of socioeconomic status on distress symptoms: a 10-year follow-up among young adults. Health Psychol. 2013;32(6):627–636. doi: 10.1037/a0029291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siahpush M, McNeill A, Borland R, Fong GT. Socioeconomic variations in nicotine dependence, self-efficacy, and intention to quit across four countries: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 3):iii71–iii75. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kowalski SD. Self-esteem and self-efficacy as predictors of success in smoking cessation. J Holist Nurs. 1997;15(2):128–142. doi: 10.1177/089801019701500205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carey MP, Kalra DL, Carey KB, Halperin S, Richards CS. Stress and unaided smoking cessation: a prospective investigation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(5):831–838. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chapman LS. Meta-evaluation of worksite health promotion economic return studies: 2012 update. Am J Health Promot. 2012;26(4):TAHP1–TAHP12. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.26.4.tahp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu SH, Nguyen QB, Cummins S, Wong S, Wightman V. Non-smokers seeking help for smokers: a preliminary study. Tob Control. 2006;15(2):107–113. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roeseler A, Anderson CM, Hansen K, Arnold M, Zhu S. Creating Positive Turbulence: A Tobacco Quit Plan for California. Sacramento: California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program; 2010. [Google Scholar]