Abstract

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to investigate the colorectal cancer (CRC) incidence and mortality prevention achievable in clinical practice with an optimized colonoscopy protocol targeting near-complete polyp clearance. The protocol consisted of: a) telephonic reinforcement of bowel preparation instructions; b) active inspection for polyps throughout insertion and circumferential withdrawal; and, c) timely updating of the protocol and documentation to incorporate the latest guidelines. Of 17,312 patients provided screening colonoscopies by 59 endoscopists in South Carolina, USA from 09/2001 through 12/2008, 997 were excluded using accepted exclusion criteria. Data on 16,315 patients were merged with the South Carolina Central Cancer Registry and Vital Records Registry data from 01/1996 – 12/2009 to identify incident CRC cases and deaths, incident lung cancers and brain cancer deaths (comparison control cancers). The standardized incidence ratios (SIR) and standardized mortality ratios (SMR) relative to South Carolina and US SEER-18 population rates were calculated. Over 78,375 person-years of observation, 18 patients developed CRC vs. 104.11 expected for an SIR of 0.17, or 83% CRC protection, the rates being 68% and 91%, respectively among the adenoma- and adenoma-free subgroups (all p<0.001). Restricting the cohort to ensure minimum 5-year follow-up (mean follow-up 6.58 years) did not change the results. The CRC mortality reduction was 89% (p<0.001; 4 CRC deaths vs. 35.95 expected). The lung cancer SIR was 0.96 (p=0.67), and brain cancer SMR was 0.92 (p=0.35). Over 80% reduction in CRC incidence and mortality is achievable in routine practice by implementing key colonoscopy principles targeting near-complete polyp clearance.

INTRODUCTION

The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) in Western populations is about 5-6%, with annual incidence rates of 48-50 per 100,000 population.1 Screening colonoscopy holds great promise for primary prevention of CRC by enabling direct visualization and removal of precancerous polyps. The National Polyp Study (NPS), a prospective clinical trial documented 76% CRC incidence reduction among 1,418 patients provided colonoscopic polypectomy over 5.9 years of mean follow-up, and a CRC mortality reduction of 53% over 15.8 years of follow-up relative to the general population. 2, 3 One academic medical center reported zero CRC incidence among persons without adenomas at initial colonoscopy over 5.34 years of mean follow-up. 4

The outcomes of community-based colonoscopy programs have shown much lower cancer protection rates. The most recent study using pooled data from the Nurses Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study reported CRC risk reductions of 43% and 56%, respectively, among persons with and without adenomas at baseline. 5 Claims-based studies from Canada reported CRC incidence reductions of 41% and 29%, respectively among males and females following a negative colonoscopy, and a 37% CRC mortality reduction among all colonoscopy recipients relative to those without a colonoscopy. 6, 7 The latter study noted that low CRC protection rates were partly accounted for by non-gastroenterologist endoscopists, which was attributed to potentially higher neoplasm miss rates by this group relative to gastroenterologist providers. 7 The US Dietary Polyp Prevention Trial documented a 26% incidence reduction among 2079 persons following colonoscopic polypectomy performed by community-based practicing endoscopists. 8 A study from Germany documented 48% prevention of advanced neoplasms among colonoscopy recipients in the previous ten years. 9 A recent meta-analysis of observational studies of community-based colonoscopy series with widely varying CRC prevention rates showed an estimated 69% CRC incidence reduction with a 95% confidence interval of 23-88%. 10 Highly variable CRC prevention rates among community-based cohorts have significantly eroded the credibility of screening colonoscopy as a CRC prevention tool.

Assuming that most CRCs develop from polyps over a decade or longer, then truly clearing the colon of all precancerous lesions should lead to excellent CRC prevention. Recent studies show that CRC prevention is indeed contingent upon the thoroughness of adenoma clearance. A recent retrospective study of 314,872 screening colonoscopy patients of 136 endoscopists classified patients into quintiles based on their endoscopists’ adenoma detection rates (ADR). The highest ADR quintile (mean endoscopist ADR 38.9%) was associated with half the adjusted interval cancer hazard (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.52, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.69) as the lowest quintile (mean ADR 16.6%). 11 Another retrospective follow-up study of 45,026 persons provided colonoscopies by 186 endoscopists reported that provider ADRs of less than 11% were associated with an interval cancer hazard ratio of 12.5 (95% CI 1.51, 103.43) relative to provider ADRs over 20%. 12 Our study adds to the literature by reporting the population-based standardized incidence and mortality ratios following colonoscopies by high-ADR endoscopists using data from an endoscopy center in South Carolina. It also presents the colonoscopy protocol used at this center.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study design

An independent, retrospective cohort study was conducted to determine CRC incidence and mortality following screening colonoscopies provided at an endoscopy center in South Carolina (SC), USA. Probabilistic matching was performed of patients provided screening colonoscopies from September 4, 2001through December 31, 2008 with the SC Central Cancer Registry's (SCCCR) cancer data from January 1, 1996 through December 31, 2009 (the last available year of complete Registry data). Appendix 3 (presented in the online supplemental materials) describes the data linkage and cancer case identification procedure used. The SCCCR is gold-certified by the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) with a consistent case completeness of at least 95%, achieved by active data collection within South Carolina, and augmented by reciprocal reporting agreements with cancer registries of 20 states.

Since September 2001 the center has implemented a polyp detection-maximizing clinical protocol (updated regularly consistent with professional society guidelines and published studies); 57 endoscopists consistently complied with the center's protocol, but two endoscopists did not comply for a period of one year. The protocol has the following features: a) An endoscopy technician manipulates the endoscope shaft and provides torque while the endoscopist manipulates the endoscope tip for polyp search and removal; b) At least two additional persons (endoscopy technician and note-taker assistant) view the video screen for abnormalities; all persons are encouraged to actively participate in the procedure; c) Polyp search and removal during both the insertion and withdrawal phases; d) Gradual insertion and circumferential withdrawal to maximize mucosal inspection; e) Active endoscope torque by the assisting technician to straighten flexures and folds, and tip manipulations by the endoscopist to maximize mucosal visualization; and, f) Retroflexion in the rectum during insertion. All patients received sedation: midazolam-meperidine up to March 2006, and thereafter, intravenous propofol administered by a nurse-anesthetist. Patients received a phone call reinforcing bowel preparation instructions two days prior to colonoscopy. All but 338 colonoscopies were performed by physicians specialized in general internal medicine, family medicine or general surgery and trained in screening colonoscopy, and 338 procedures were done by a colorectal surgeon during a one-year period. The training process, technical assistance and on-site availability of expert backup are documented. 13 Patients with histologically significant findings, multiple large hyperplastic polyps, or a carpet-like patch (despite the lack of adenomatous features), were advised to return for surveillance colonoscopy one to five years later, per prevailing professional consensus and the US MultiSociety Task Force guidelines when they became available. 14, 15 Patients with polyp tissue not adequately destroyed at initial colonoscopy or an incomplete colonoscopy for any reason (including inadequate bowel preparation) were advised to return for a repeat procedure within 6-12 weeks. The remaining patients were advised to return for screening after ten years. 14, 15 Compliance and timing of repeat/surveillance colonoscopy was at the patient's discretion (i.e., no active follow-up).

Patients

The study sample was drawn from 17,312 persons provided initial colonoscopies by 59 endoscopists between September 4, 2001 and December 31, 2008. All polyps were removed except invasive, very large, or highly vascular polyps, which were referred for surgical excision. Histopathology examination was done for all polyps except for clusters of morphologically similar small polyps <2 mm, or a carpet-like patch, in which case a sample was collected for histopathology, and the remaining lesion(s) excised or destroyed. Multiple polyps with similar gross appearance from the same colorectal segment were submitted in a single jar to the pathology laboratory. Villous/tubulovillous-appearing polyps were submitted separately. All histopathology assessments were done by four community-based laboratories using pathologists with gastrointestinal subspecialty training since 2006. Bowel preparation status was documented as excellent, good, fair or poor. 16 Data quality within the center's colonoscopy and polyp databases was verified by sample chart review as previously reported. 13 Missing/discrepant data were rectified based on chart review.

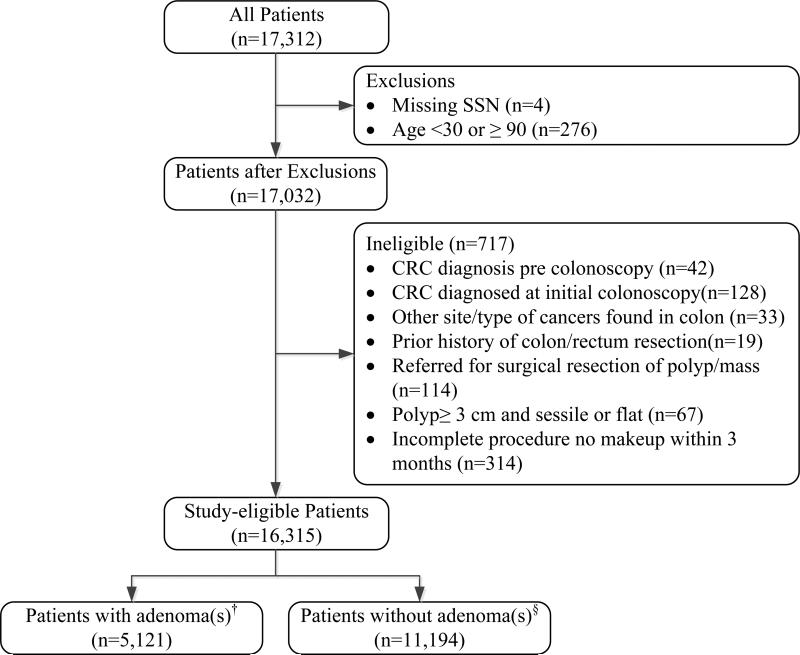

Standard exclusion criteria used in previous cohort studies were applied, as follows: CRC predating or diagnosed at initial colonoscopy; other cancers (e.g. carcinoids, cancers infiltrating into the colon); sessile polyps greater than 3 cm in diameter; patient referred for surgical resection of clinically determined invasive polyp or obstructing mass; history of prior bowel resection; or incomplete initial colonoscopy without repeat colonoscopy within three months. 3, 17 Figure 1 shows the study cohort selection protocol.

Figure 1.

Patients with initial screening colonoscopy eligible for study

No information was available on family history or CRC-predisposing conditions such as Lynch syndrome or familial polyposis. However nearly all cases were screening colonoscopies. Patients with documented colorectal pathology in the referral notes were excluded (19 cases).

Comparison groups

The South Carolina general population and the US SEER-18 population were the comparison groups. The expected number of incidence cases in the study cohort each year was generated by applying the published population-wide, age-, sex-, race- specific annual incidence rates from 2001 through 2009 for the comparison populations to the study cohort person-years of observation (PYO). 18, 19 The population incidence rates do not reflect a screening- or surveillance-naïve population, but instead reflect the observed incidence including the effects of existing CRC prevention efforts. The standardized incidence ratio (SIR) was the observed divided by the expected number of incident cases.

End points

Incident CRC was the primary end point, determined by linking patient data with the SCCCR cancer database for 1996-2009 which allowed for identification of pre-existing CRC in patients. This was accomplished using LinkPlus®, a probabilistic record linkage program developed by the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. A second censoring end point was death from any cause ascertained from the South Carolina Division of Vital Records database. All persons with a CRC diagnosis or CRC cause of death, the latter cross-verified with the SCCCR database were defined as interval CRC cases. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of South Carolina and of the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control.

Statistical analysis

PYOs contributed by all study-eligible patients to each calendar year were summarized by age group and the total number of expected CRC cases was calculated. We calculated the SIRs relative to the reference population rates along with 95% confidence intervals assuming a chi-squared distribution for the SIR, and using a two-sided p-value of 0.05 for statistical significance.19 SIRs were calculated for the total cohort, and separately for the adenoma- and adenoma-free subgroups. For interval CRC cases, we report the demographic characteristics, adenoma status at initial colonoscopy, colonoscopy-to-cancer interval, diagnosed at surveillance colonoscopy (or otherwise), SEER summary stage, tumor anatomic location, and presence of additional primary cancers at other sites.

The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was calculated based on CRC deaths certified in the Vital Records Registry and cross-verified with the Cancer Registry (to exclude cancer site-misclassified deaths). Additionally we compared the SIR and SMR for CRC with two “control” cancers unlikely to be affected by a CRC prevention program: primary lung cancer, a high volume cancer (control cancer SIR), and primary brain cancer, a low volume cancer with a known stable incidence and mortality, and unlikely to be misclassified on death certificates (control cancer SMR).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of the 16,315 study-eligible patients at baseline. The sample mean age was 57.5 years (SD 10.3 years), 53.3% were female, and 49.4% were African American. Colonoscopy was complete in 98.3% of cases (cecum intubated, determined by either or both of two criteria, visualizing the appendiceal orifice and/or both cusps of the ileo-cecal valve or crow foot in the cecum (with photo-documentation in all cases), and intubating the ileal tip followed by identifying lymphoid follicles in the ileum). The mean insertion and withdrawal times were 14.2 and11.5 minutes, respectively (median 11.0 and 10.0 minutes). Of total patients, 5,121 had adenoma(s) at initial colonoscopy, an adenoma detection rate (ADR) of 31.4% (36.6% among males, 27.0% among females). The advanced adenoma rate was 5.2% (>=1 cm in size, villous/tubulovillous histology, or high-grade dysplasia), 4.0% of patients had three or more adenomas, and 7.8% had an advanced adenoma or three or more adenomas. The median follow-up period was 4.91 years for a total of 78,375 PYOs (mean 4.80 years, range 1.0 – 8.3 years, except for three patients with less than one year of follow-up due to attaining the exclusion age group).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and adenoma status of the study cohort at initial colonoscopy

| Characteristics | Total (n=16,315) | Adenoma (n = 5,121) | No adenoma* (n = 11,194) | P value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 57.7(10.3) | 60.2(10.0) | 56.6(10.2) | P<0.001 |

| Age group | Number of patients (%) | P<0.001 | ||

| 30-49 years | 2,925 (17.9) | 607 (11.9) | 2,318 (20.7) | |

| 50–59 years | 7,275 (44.6) | 2,113 (41.3) | 5,162 (46.1) | |

| 60–69 years | 3,978 (24.4) | 1,480 (28.9) | 2,498 (22.3) | |

| 70–79 years | 1,753 (10.8) | 738 (14.4) | 1,015 (10.9) | |

| 80–89 years | 384 (2.4) | 183 (3.6) | 201 (1.8) | |

| Gender | P<0.001 | |||

| Male | 7,525 (46.1) | 2,756 (53.8) | 4,769 (42.6) | |

| Female | 8,699 (53.3) | 2,348 (45.9) | 6,351 (56.7) | |

| Missing | 91 (0.6) | 17 (0.3) | 74 (0.7) | |

| Race*** | P<0.001 | |||

| Whites | 7,577 (46.4) | 2,539 (49.6) | 5,038 (45.0) | |

| African American | 8,051 (49.4) | 2,384 (46.6) | 5,667 (50.6) | |

| Other | 596 (3.7) | 181 (3.5) | 415 (3.7) | |

| Missing | 91 (0.6) | 17 (0.3) | 74 (0.7) | |

| Cohort distribution by presence of adenomas | ||||

| Patients with at least one polyp | 9,918 (60.8) | 5,121 | 4,797 | P<0.001 |

| Patients with at least one adenoma† | 5,121 (31.4) | 5,121 | - | - |

| Patients with at least one advanced adenoma†‡ | 850 (5.2) | 850 | - | - |

| Patients with advanced adenoma and/or ≥3 non-advanced adenomas | 1,279 (7.8%) | 1,279 | - | - |

| Persons without any polyps | 6,397 (39.2) | - | 6,397 | - |

| Cohort distribution by number of adenomas found† | ||||

| 1 | 3,198 (19.6) | 3,198 | - | - |

| 2 | 1,146 (7.0) | 1,146 | - | - |

| ≥3 | 650 (4.0) | 650 | - | - |

| No adenoma | 11,194 (68.8) | - | 11,194 | - |

| Cohort distribution by number of colonoscopies during the study period | P<0.001 | |||

| 1 (initial colonoscopy only) | 12,764 (78.2) | 3,032 (59.2) | 9,732 (86.9) | |

| 2 procedures | 3,002 (18.4) | 1,650 (32.2) | 1,352 (12.1) | |

| ≥3 procedures | 549 (3.4) | 439 (8.6) | 110 (1.0) | |

| Polyp characteristics | ||||

| Most advanced polyp† | ||||

| Non-advanced | 8,951 (54.9) | 4,154 (81.1) | 4,797 (42.9) | P<0.001 |

| Advanced‡ | 850 (5.2) | 850 (16.6) | - | |

| No polyp | 6,397 (39.2) | - | 6,397 (57.2) | |

| Polyp anatomic location — number (%)¶ | ||||

| Distal colon only | 4,954 (30.4) | 1,519 (29.7) | 3,435 (30.7) | P<0.001 |

| Any in proximal colon | ||||

| - Proximal only | 2,297 (14.1) | 1,551 (30.3) | 746 (6.7) | P<0.001 |

| - Distal and proximal | 2,543 (15.6) | 1,975 (38.6) | 568 (5.1) | P<0.001 |

| No polyp | 6,397 (39.2) | - | 6,397 (57.2) | |

| Missing data on polyp location | 124 (0.8) | 76 (1.5) | 48 (0.4) | P<0.001 |

| Person-years of observation | ||||

| Total for cohort | 78,375 | 24,539 | 53,836 | |

| Median follow-up duration in years (range) | 4.91(0.27,8.33) | 4.94(0.41,8.33) | 4.88(0.27,8.33) | |

| Mean | 4.80 | 4.79 | 4.81 | |

Includes patients without polyps and non-adenomatous polyps.

Student's t-test used for age and chi-square tests for count variables.

Race was self-reported.

Includes 95 patients with missing pathology reports.

Advanced adenomas were those >=1.0 cm in diameter, tubulovillous/villous histology, or high-grade dysplasia. Of 850 patients with advanced adenomas, 401 (47.2%) had tubular adenomas ≥1.0 cm. (Because patients with cancer at initial colonoscopy were excluded, we report advanced adenoma rates, not advanced neoplasm rates.)

Defined as proximal if located in the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon, and distal if located in the splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, or rectum.

Colorectal and control cancer incidence/mortality and Standardized Incidence/Mortality Ratios

Table 2 presents the SIRs and SMRs for the study cohort. A total of 18 persons developed interval CRC vs. 104.1 expected (per South Carolina incidence rates) for an SIR of 0.17 (95% CI, 0.10, 0.27). The SIR was 0.32 among persons with adenoma(s) at baseline (12 cases vs. 37.6 expected; p<0.001), and 0.09 among those without adenomas (6 cases vs. 66.6 expected; p<0.001). SIRs based on SEER-18 rates were almost identical. The cohort SIRs translate to a CRC incidence prevention rate of 82-83%. Four CRC deaths were observed vs. 36.0 expected for a SMR of 0.11 (95% CI 0.03, 0.26), translating to a CRC mortality prevention rate of 89%.The study cohort had an SIR for lung cancer of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.81, 1.13; p=0.67; 143 observed cases vs. 149.5 expected). The SMR for brain cancer was 0.92 (95% CI 0.30, 2.02; p=0.35), 5 observed deaths vs. 5.4 expected. Figure 2 shows the annual observed vs. expected incidence for CRC and lung cancer, and the observed vs. expected CRC deaths for the periods 2002-2005 and 2006-2009.

Table 2.

Standardized incidence and mortality ratios for colorectal cancer and control cancers relative to the South Carolina general population

| Study cohort | Standardized incidence/mortality ratios vs. South Carolina general population rate (2001-2009)* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Person-years of observation | Observed | Expected** | Ratio (95% CI) | Reduction achieved, % (95% CI) | P value*** | |

| Colorectal cancer | |||||||

| All patients | 16,315 | 78,375 | 18 incidence cases | 104.11 | SIR 0.17 (0.10,0.27) | 83 (73, 90) | P<0.001 |

| a) Adenoma(s) present | 5,121 | 24,539 | 12 incidence cases | 37.56 | SIR 0.32 (0.17, 0.55) | 68 (45, 83) | P<0.001 |

| b) No adenoma(s) | 11,194 | 53,836 | 6 incidence cases | 66.55 | SIR 0.09 (0.03, 0.18) | 91 (82, 97) | P<0.001 |

| Colorectal cancer deaths | 16,315 | 78,230 | 4 deaths | 35.95 | SMR 0.11 (0.03, 0.26) | 89 (74, 97) | P<0.001 |

| Control cancers | |||||||

| Lung cancer incidence (control cancer to compare incidence reduction) | 16,315 | 78,375 | 143 incidence cases | 149.52 | SIR 0.96 (0.81,1.13) | 4 (−13, 19) | P=0.67 |

| Brain cancer deaths (control cancer to compare mortality reduction) | 16,315 | 78,230 | 5 deaths | 5.42 | SMR 0.92 (0.30,2.02) | 8 (−102, 70) | P=0.35 |

SCCCR= South Carolina Central Cancer Registry, CI=confidence interval

Based on SEER-18 rates, the SIR for CRC was 0.18 (expected cases: 102.6), and the SMR was 0.11 (expected cases: 36.0).

Expected incidence cases are based on 2001-2009 Cancer Registry data (http://www.scdhec.gov/administration/phsis/scccr/AboutRegistry.htm Accessed on February 15 2013); expected deaths are based on 2002-2009 data from the SC Division of Vital Records.

Significance relative to (an SIR of) 1.0 (zero rate reduction)

Figure 2.

Cumulative observed incidence of, and deaths from colorectal cancer vs. expected per South Carolina population rates, and comparison with lung cancer incidence vs. expected

Additional analysis was carried out, restricting the sample to those with a minimum follow-up period of 5 years (cohort accrual period 2001-2004; n=7,896 patients). The mean follow-up periods were 6.64 years overall, 6.58 years for the adenoma group, and 6.67 years for the nonadenoma group). The CRC protection rates remained the same, 85% overall (95% CI 74%, 93%), 81% in the adenoma group (95% CI 57%, 94%), and 87% in the adenoma-free group (95% CI 73%, 95%), all p<0.001 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) Incidence cases and standardized incidence ratios among the 2001-2004-accrued cohort (minimum 5-year follow-up for all patients)

| Study cohort | Standardized incidence ratios | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vs. South Carolina general population rate 2001-2009 | |||||||

| Number | Person-years of observation | Observed CRC cases | Expected | Ratio (95% CI) | Reduction achieved % (95% CI) | P value** | |

| 2001-2004 cohort | |||||||

| All patients* | 7,896 | 52,418 | 11 | 74.55 | SIR 0.15 (0.07,0.26) | 85 (74,93) | P<0.001 |

| a)Adenoma present | 2,507 | 16,521 | 5 | 26.89 | SIR 0.19 (0.06,0.43) | 81 (57,94) | P<0.001 |

| b) No adenoma | 5,389 | 35,897 | 6 | 47.66 | SIR 0.13 (0.05,0.27) | 87 (73,95) | P<0.001 |

CI=confidence interval

Median follow-up 6.60 years, mean 6.58 years (range 1.86 – 8.33; follow-up less than 5 years is due to patients attaining study exclusion age.)

Significance relative to (an SIR of) 1.0 (zero rate reduction)

Characteristics of interval CRC cases

The observed 18 interval CRC cases were diagnosed 13-93 months following initial colonoscopy; half of them were diagnosed at a surveillance colonoscopy (Table 4). None were diagnosed at anatomic locations of polyps found at prior colonoscopy. Eight patients were African American and eight were female. Seven cases occurred in the left colon (including rectum), two in the appendix, and nine in the remainder of the right colon. One case was a malignant rectal carcinoid. Three patients were diagnosed with distant metastasis (at 29, 43, and 51 months following initial colonoscopy).

Table 4.

Characteristics of 18 patients with incident colorectal cancer following initial colonoscopy*

| At baseline colonoscopy | Patient serial number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Gender | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | |

| Race | African American | White | African American | White | White | African American | |

| Age(years) | 40 | 66 | 66 | 63 | 61 | 65 | |

| Procedure year | 2001 | 2005 | 2002 | 2005 | 2001 | 2007 | |

| Number of adenomas/Histology/Largest adenoma(cm) | 0/-/- | 2/Tubular/0.3 (+1 polyp) | 4/Tubular/0.3 | 1/Tubular/0.5 | 0/-/- | 1/Tubular/0.5 (+3 polyps) | |

| Adenoma locations | - | Mid-transverse | Mid-ascending, Mid-transverse, Proximal-transverse |

Mid descending | - | Proximal-transverse | |

| At colorectal cancer diagnosis | Age(years) | 45 | 69 | 68 | 66 | 66 | 66 |

| Time to cancer since colonoscopy (months) | 63 | 38 | 29 | 43 | 63 | 13 | |

| Detected at surveillance colonoscopy? | Yesa | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | |

| Cancer grade | Grade II | Grade II | Grade missing | Grade IV | Grade II | Grade missing | |

| Cancer anatomic location(s) | Cecum | Ascending | Splenic flexure | Sigmoid | Cecum | Rectum, NOS | |

| Histology | AdenoCa | AdenoCa | Carcinoma | ** | AdenoCa | Carcinoid, Malignant | |

| SEER stage | Local | Local | Distant metastasis | Distant metastasis | Regional, DE and LN | Local | |

| Additional primary cancer(s) and site(s) | No | No | Yes (Corpus Uteri cancer,) | No | Yes-3(Sites not known) | No | |

| Additional primary predated CRC? | - | - | No | - | *** | - | |

| Survival status as of December 31, 2009 | Alive | Alive | Alive | Died (Cancer cause) | Alive | Alive | |

| At baseline colonoscopy | Patient serial number | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | |

| Race | White | African American | White | Other | African American | African American | |

| Age (years) | 68 | 52 | 78 | 62 | 63 | 68 | |

| Procedure year | 2002 | 2002 | 2002 | 2001 | 2003 | 2008 | |

| Number of adenomas/Histology/Largest adenoma(cm) | 1/Tubular/0.4 | 0/-/- | 3/Tubulovillous/0.5 | 0/-/- | 1/Tubular/1.0 (+1 polyp) | 1/Tubular/0.3 | |

| Adenoma location(s) | Rectum | - | Mid-transverse, Mid-descending | - | Proximal-ascending | Cecum | |

| At colorectal cancer diagnosis | Age (years) | 74 | 57 | 81 | 70 | 67 | 69 |

| Time to cancer since colonoscopy (months) | 81 | 63 | 40 | 93 | 60 | 17 | |

| Detected at surveillance colonoscopy? | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Cancer grade | Grade I | Not stated | Grade II | Grade II | Grade II | Grade II | |

| Cancer anatomic location(s) | Transverse | Rectum, NOS | Cecum | Ascending | Appendix | Rectum, NOS | |

| Histology | AdenoCa | Stromal sarcoma | AdenoCa | Mucinous AdenoCa | AdenoCa | AdenoCa | |

| SEER stage | Local | Regional, DE | Local | Regional, LN | Local | Local | |

| Additional primary cancer(s) and site(s) | Yes*** | Yes (Prostate cancer) | Yes (Kidney, Renal Pelvis) | No | No | Yes (Chronic lymphocytic leukemia) | |

| Additional primary predated CRC? | *** | No | No | - | - | Yes | |

| Survival status as of December 31, 2009 | Alive | Died (Non-cancer cause) | Alive | Alive | Alive | Alive | |

| At baseline colonoscopy | Patient serial number | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Male | |

| Race | White | African American | White | White | White | African American | |

| Age (years) | 78 | 63 | 54 | 61 | 80 | 63 | |

| Procedure year | 2005 | 2008 | 2004 | 2002 | 2004 | 2005 | |

| Number of adenomas/Histology/Largest adenoma(cm) | 1/Tubular/0.3 | Missing histology/-/2.5 (4 polyps) | 0/-/- | 1/Tubulovillous/0.8 | 0/1 Normoplastic polyp/0.3 | 1/Tubular/0.8 | |

| Adenoma locations | Proximal-ascending | Sigmoid, Mid-ascending, Proximal-descending | - | Missing | Distal-ascending | Mid-descending | |

| At colorectal cancer diagnosis | Age(years) | 80 | 65 | 57 | 68 | 81 | 65 |

| Time to cancer since colonoscopy (months) | 32 | 21 | 51 | 81 | 18 | 22 | |

| Detected at surveillance colonoscopy? | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | |

| Cancer grade | Grade II | Grade II | Grade II | Grade II | Not stated | Grade III | |

| Cancer anatomic location(s) | Hepatic flexure, ascending | Cecum | Appendix | Splenic flexure | Sigmoid, cecum | Rectosigmoid junction | |

| Histology | AdenoCa | AdenoCa | Mucinous AdenoCa | AdenoCa | Villous AdenoCa | AdenoCa | |

| SEER stage | Local | Regional, DE | Distant metastasis | Regional, DE and LN | Local | Regional, DE | |

| Additional primary cancer (s) and site(s) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (Prostate cancer) | |

| Additional primary predated CRC? | - | - | - | - | - | Yes | |

| Survival status as of December 31, 2009 | Died (Non-cancer cause) | Alive | Alive | Alive | Died (Non-cancer cause) | Alive |

Surveillance colonoscopy was provided early because of patient family history.

Surveillance colonoscopy was provided early because of poor bowel preparation at the first procedure.

AdenoCa=adenocarcinoma, DE=direct extension, NOS=not specified, LN=lymph node

ICD-O-3 codes C180, C182-C189, C199, C209 and C260, used to identify colon and rectum cancer, C181 for appendix cancer.

Histology terminology used by reporting facility not used in the ICD-O-3 dictionary (http://seer.cancer.gov/icd-o-3/sitetype.icdo3.d20121205.pdf).

Other primaries site not specified because they were diagnosed either pre-1996 (before the study linkage period) or in a state without a data exchange agreement with the SC Central Cancer Registry.

Note:”+ x number of polyps” indicates the additional polyp(s) were either normoplastic or hyperplastic.

DISCUSSION

The patients in our cohort experienced CRC incidence and mortality reductions of 83% and 89%, respectively, when compared to the expected rates in the SEER-18 and South Carolina populations. These rate reductions are the largest ever reported for incidence and mortality by colonoscopy. Because colonoscopy screening rates among the comparison populations ranged between 13.4% in 2005 and 36.4% in 2010,20 the results represent an underestimate of the full protective effect of screening colonoscopy; i.e., the true CRC protective effect of colonoscopy compared to no screening may exceed 90%.

These excellent results are most likely explained by the high ADRs of the endoscopists, and complement the findings of recent studies with similarly high ADRs, as well as the long-term outcome results of the NPS. 2,3,11,12 The study center's ADR of 31.4% (36.6% among men and 27.0% among women) is higher than typical community-based ADRs of 9.8% to 19.3% in the US. 5, 21 Our follow up also is comparable to those of most recent studies. 11, 12 While the recent studies investigated the relative cancer hazard ratios among patients classified by their endoscopists’ ADR, our study goes one step further and documents the long-term patient outcomes following high-ADR endoscopy compared to the general population. Our finding of 91% CRC prevention among patients with a negative screening colonoscopy is similar to an earlier study reporting a zero incidence.4

The completeness of the South Carolina cancer registry (99.7% completeness certified in 2012) allowed us to use the general population for comparison. Lung cancer incidence and brain cancer mortality rates in the study population were indistinguishable from those in the general population, and therefore rule out potential “healthy population” bias, as well as strongly support our conclusion that the observed large CRC reduction is attributable to colonoscopy. Other facts that argue against a healthy population bias are the high ADR and large proportion of African Americans, a racial group documented to have higher adenoma rates than Whites. 22

This study has several of the limitations of a retrospective study, including the lack of data on CRC risk factors and family history, as well as the lack of active follow up. However, as in prospective trials all endoscopists were required to comply with clearly specified endoscopy technique (two endoscopists who did not comply for one year left the center), all patients received personal instructions reinforced by a phone call prior to colonoscopy, and all colonoscopy data were documented in real-time, although not by the research investigators. As a result, the findings support the concept that reductions in CRC incidence and mortality that are comparable to those produced in clinical trials are attainable by colonoscopy screening under routine practice conditions.

Patients with CRC at initial colonoscopy were excluded from this study, consistent with published studies. Thus CRC deaths among cases found at screening colonoscopy were excluded from the observed cohort mortality, while the comparison population's mortality rate included such deaths. Excluding cancer cases found at screening is essential, because the efficacy of screening colonoscopy represents future mortality reductions among screened beneficiaries who are protected from incident CRC by removal of premalignant lesions (i.e., polyps). Examining the profile of excluded patients (outcomes shown in Appendix Table 1), it is observed that the mean age of patients with cancer at initial colonoscopy (n=128) was 61.4 years (SD 10.3), compared to the study cohort's mean age of 57.5 years (SD 10.3), p<0.0001, with 73.4% of the former being over 55 years of age. These data support that timely initiation of first screening colonoscopy (at 50 years of age), followed by surveillance, over time, could produce >80% CRC incidence reduction year after year resulting in a population-wide CRC mortality reduction of >90%.

A high ADR alone is not enough to reduce CRC mortality. The acronym CLEAR represents the three critical steps required to realize the full potential of CRC prevention in practice: Clean the colon, Look Everywhere, and Abnormality Removal. 23 Weaknesses in any of these links decrease the effectiveness of colonoscopy. The South Carolina endoscopy group has diligently minimized the weak links through protocolized elements implemented early on, which are documented to improve polyp detection rates. Increased ADRs are documented with: gradual colonoscope withdrawal, 24 having more observers/assistant watching the video-screen, 25-27 and, limited number of procedures per day per endoscopist. 28 Other literature also supports the study group's emphasis on gradual spiral withdrawal to work the folds, which maximizes mucosal exposure including inter-haustral areas. 29 In the study cohort all interval CRCs occurred at anatomic locations other than the polypectomy sites at baseline colonoscopy, validating the completeness of polypectomies performed by the group's endoscopists. The major adverse event rate of the group is low and comparable to those of others. 13,30, 31

To realize similar outcomes in other community-based settings, certain hurdles must be overcome. First, most endoscopy centers appear to benchmark their ADRs to the ACG/ASGE's overall 20% ADR guideline, first established in 2006, 16 and likely reinforced by the 20% cut-off used by Kaminski et al. 12 Recent literature and the present study indicate the need to revisit this guideline. Our findings and those of Corley et al suggest the need for a maximalist approach to polyp detection as each 1% increase in ADR is associated with a 3% decrease in interval CRC. 11 Second, more individualized or in-person colon cleansing instructions along with ensuring an undisturbed two-day preparation by the patient will improve bowel preparation.32, 33 Third, the unrealistic fixed time slot schedule irrespective of findings, e.g., 30 minutes, applied in most endoscopy centers should be revisited. 34 Fourth, self-developed colonoscopy protocols focused on quality maximization rather than patient through-put will encourage adherence by endoscopists and overcome resistance to perceived loss of clinical autonomy. The United Kingdom's (UK) National Health Service (NHS) limits screening colonoscopy to NHS-certified endoscopists adhering to a predefined protocol verified in person, 35 which has greatly improved colonoscopy quality in the UK.

In summary, a group of 59 endoscopists collectively delivered 82-83% CRC prevention, comparable to the results of the only randomized clinical trial with long-term follow-up. 2, 3 These encouraging results support the potential of well-performed colonoscopy to prevent nearly all CRC, and call for further research into the technical aspects of the protocol as related to ADR, completeness of polypectomy, patient safety, and cost-effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and impact.

Recent studies suggest that the promise of screening colonoscopy to prevent colorectal cancer is contingent upon the thoroughness of adenoma clearance. These studies presented the relative cancer hazard risks of patients categorized by their endoscopists’ adenoma detection rates (ADR). Our study completes the “other half” of the picture by quantifying the population-based cancer protection rate achieved by very high-ADR endoscopists. It contributes key evidence that a high rate of colorectal cancer protection is achievable in routine practice.

Acknowledgements

This work was primarily supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R15 CA156098-01, Sudha Xirasagar, Principal Investigator) and by the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota, as well as a NCI Established Investigator award (K05 CA136975; Hebert, JR, PI) and grant U54 CA153461 (Hebert JR, PI) from the NCI's Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. We are grateful to the South Carolina Medical Endoscopy Center, Columbia, South Carolina for providing access to the data, facilitating data collection from primary records by the study team, and facilitating the South Carolina Central Cancer Registry to perform the data linkages. None of the authors have any conflict of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. GLOBOCAN Estimated Colorectal Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, Stewart ET, Waye JD. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imperiale TF, Glowinski EA, Lin-Cooper C, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Five- year risk of colorectal neoplasia after negative screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1218–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Imamura Y, Willett WC, et al. Long-Term Colorectal-Cancer Incidence and Mortality after Lower Endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095–105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of colonoscopy and death from colorectal cancer. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150:1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh H, Nugent Z, Mahmud SM, Demers AA, Bernstein CN. Predictors of colorectal cancer after negative colonoscopy: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:663–73. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.650. quiz 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung K, Pinsky P, Laiyemo AO, Lanza E, Schatzkin A, Schoen RE. Ongoing colorectal cancer risk despite surveillance colonoscopy: the Polyp Prevention Trial Continued Follow-up Study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2010;71:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms after colonoscopy: population-based study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:89–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner H, Stock C, Hoffmeister M. Effect of screening sigmoidoscopy and screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2467. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, de Boer J, Fireman BH, Schottinger JE, Quinn VP, Ghai NR, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795–803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xirasagar S, Hurley TG, Sros L, Hebert JR. Quality and safety of screening colonoscopies performed by primary care physicians with standby specialist support. Medical care. 2010;48:703–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e358a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Levin TR, Pickhardt P, Rex DK, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2008;58:130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for colorectal cancer Recommendation statement. 2014:2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, Safdi MA, Faigel DO, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pabby A, Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Burt R, Kikendall JW, Lance P, Shike M, Lanza E, Schatzkin A. Analysis of colorectal cancer occurrence during surveillance colonoscopy in the dietary Polyp Prevention Trial. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2005;61:385–91. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02765-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.South Carolina Community Assessment Network Cancer Incidence: Full (Research) File. 2013:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Registries Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases. 2010 Nov; Sub (2000-2008) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Health Interview Survey. 2013;2005:2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S, Halm EA, Rockey DC, Hammons M, Koch M, Carter E, Valdez L, Tong L, Ahn C, Kashner M, Argenbright K, Tiro J, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Fecal Immunochemical Test Outreach, Colonoscopy Outreach, and Usual Care for Boosting Colorectal Cancer Screening Among the Underserved: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieberman DA, Holub JL, Moravec MD, Eisen GM, Peters D, Morris CD. Prevalence of colon polyps detected by colonoscopy screening in asymptomatic black and white patients. Jama. 2008;300:1417–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Groen PC. Advanced systems to assess colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:699–716. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Greenlaw RL. Effect of a time-dependent colonoscopic withdrawal protocol on adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1091–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchner AM, Shahid MW, Heckman MG, Diehl NN, McNeil RB, Cleveland P, Gill KR, Schore A, Ghabril M, Raimondo M, Gross SA, Wallace MB. Trainee participation is associated with increased small adenoma detection. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011;73:1223–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters SL, Hasan AG, Jacobson NB, Austin GL. Level of fellowship training increases adenoma detection rates. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:439–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogart JN, Siddiqui UD, Jamidar PA, Aslanian HR. Fellow involvement may increase adenoma detection rates during colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2841–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanaka MR, Deepinder F, Thota PN, Lopez R, Burke CA. Adenomas are detected more often in morning than in afternoon colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1659–64. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.249. quiz 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HN, Raju GS. Bowel preparation and colonoscopy technique to detect non-polypoid colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010;20:437–48. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arora G, Mannalithara A, Singh G, Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Risk of perforation from a colonoscopy in adults: a large population-based study. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2009;69:654–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rabeneck L, Paszat LF, Hilsden RJ, Saskin R, Leddin D, Grunfeld E, Wai E, Goldwasser M, Sutradhar R, Stukel TA. Bleeding and perforation after outpatient colonoscopy and their risk factors in usual clinical practice. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1899–906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, Shemesh I, Morad I, Plaut S, Weiss E, Sulkes J, Fraser G, Niv Y. A patient education program is cost-effective for preventing failure of endoscopic procedures in a gastroenterology department. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1786–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kakkar A, Jacobson BC. Failure of an Internet-based health care intervention for colonoscopy preparation: a caveat for investigators. JAMA internal medicine. 2013;173:1374–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boroff E, Crowell M, Leighton J, Faigel D, Gurudu S, Ramirez F. The relationship between withdrawal time and intubation time in colonoscopy: correlation with adenoma detection rate (ADR). Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:s806–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy Accreditation of Screening Colonoscopists, BCSP guidelines. The JAG. 2013;2013 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.