Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to determine if shRNA constructs targeting insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 can rehabilitate decreased serum testosterone concentrations in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats.

Material/Methods

After 12 weeks of intracavernous administration of IGFBP-3 shRNA, intracavernous pressure responses to electrical stimulation of cavernous nerves were evaluated. The expression of IGFBP-3 at mRNA and protein levels was detected by quantitative real-time PCR analysis and Western blot, respectively. The concentrations of serum testosterone and cavernous cyclic guanosine monophosphate were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Results

After 12 weeks of intracavernous administration of IGFBP-3 shRNA, the cavernosal pressure was significantly increased in response to the cavernous nerves stimulation compared to the diabetic control group (p<0.01). Cavernous IGFBP-3 expression at both mRNA and protein levels was significantly inhibited. Both serum testosterone and cavernous cyclic guanosine monophosphate concentrations were significantly increased in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group compared to the diabetic control group (p<0.01).

Conclusions

These results suggest that IGFBP-3 shRNA may rehabilitate erectile function via increases of concentrations of serum testosterone and cavernous cyclic guanosine monophosphate in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats.

MeSH Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1; Erectile Dysfunction; Methyltestosterone

Background

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) for all age groups worldwide was estimated to be 2.8% in year 2000 and it is quite clear that male patients with DM are 3 times more likely to develop erectile dysfunction (ED) than those who do not have DM [1,2]. In streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, hypogonadism was often observed [3]. Thus, the erectile process has been shown to be strongly androgen-sensitive, at least in the rat model [4]. Testosterone substitution can reverse hypogonadism and diabetes-induced penile hyporeactivity to cavernous nerve stimulation in vivo in rats, along with increased neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) expression [4]. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) is a member of the growth factor family and it is generally believed that the increased expression of IGFBP-3 is associated with ED in diabetic rats [5,6], while IGFBP expression is suppressed by androgens [7].

It is well known that short hairpin RNA (shRNA) is emerging as a technology to silence gene expression by inhibiting mRNA translation and/or inducing its degradation, including in the penis [8]. In the current study, we investigated whether short hairpin ribonucleic acid constructs targeting IGFBP-3 (IGFBP-3 shRNA) can rehabilitate decreased testosterone concentrations in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

Material and Methods

IGFBP-3 shRNA Constructs

To design IGFBP-3 shRNA construct, the rat IGFBP-3 gene sequence (GI: M31837) was analyzed for a potential siRNA target using the web-based siRNA target finder and design tool provided on the Ambion website (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). Double-stranded siRNAs (nucleotide position: 611) were transcribed in vitro using the Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The inhibitory siRNA (5′-GCGCTACAAAGTTGACTATGA-3′, nucleotide position 611) was then cloned into the pGPU6/GFP/Neo plasmid vector (2nd version, Ambion) as a short hairpin DNA sequence (5′ sense strand: 5′-CACCGCGCTACAAAGTTGACTATGATT CAAGAGATCATAGTCAACTTTGTAGCGCTTTTTTG-3′) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pGPU6/GFP/Neo- IGFBP-3 shRNA plasmid was purified using the Endo-free Maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Plasmids were quantitated by spectrophotometry and prepared in 0.9% saline solution at a concentration of 1.0 μg/μL.

Experimental animals

Twenty-seven adult SPF male Wistar rats (age 3 months, weight 310–330 g, certificated No. scxk[E]2008-0005) were obtained from Hubei Laboratory Animal of Research Center (Wuhan, China). The Wuhan University Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures in the current study. All rats were randomly divided into 3 groups with 9 rats each. Group 1 included 9 age-matched control rats that received i.p. injections of citrate buffer (100 mmol/L citric acid and 200 mmol/L disodium phosphate, pH 7.0). The other 18 rats all received i.p. injection of STZ at a dose of 65 mg/kg. Rats were considered diabetic if blood glucose levels were greater than 200 mg/dL (Table 1). Animals received 60 μl citrate buffer (Group 1 and 2) and 60 ul lipofectamine-plasmid complex (10 μg/kg) (Group 3) into the corpus cavernosum 12 weeks after STZ induction. Half the dose was administered in each crus. During intracavernosal injection, a constriction band was applied at the base of the penis, and the needle was left in place for 5 min to allow the medication to diffuse throughout the cavernous space [9].

Table 1.

Total body weight and blood glucose level in rats of three groups (n=9).

| Normal control | Diabetes | IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | |||

| Initial | 319±3 | 314±2 | 319± 4 |

| Final | 540±4* | 258±7* | 267±8* |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | |||

| Initial | 93±6 | 103±8 | 107±5 |

| Final | 105±2 | 307±11* | 318±14* |

Data were expressed as mean ±SD.

p<0.01, compared to initial.

Measurement of erectile responses

At 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA administration, erectile function was evaluated by measuring intracavernous pressure (ICP) following electrostimulation of the cavernous nerves, as previously described [9]. The ratio of maximal ICP-to-mean arterial pressure (MAP) (ICP/MAP) and total ICP (area under curve) were recorded for each rat. All rats were the sacrificed with an i.p. overdose of pentobarbital (80 mg/kg). The penile shaft was collected for further analyses and whole blood samples from both systemic and penile shaft were also collected with serum obtained after clotting for 30 min at room temperature following centrifugation. All the serum samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen after collection and stored at −80°C for further analyses.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from rat penile samples using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen, Merelbeke, Belgium) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and re-suspended in RNAse-free water. Total RNA was stored at −80°C until analysis of IGFBP-3 mRNA levels by MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad laboratories, Hercules, CA) with the following primers:

IGFBP-3, forward 5′-AGCCGTCTCCTGGAAACACC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCCGCTTTCTGCCTTTGG-3′;

Quantitative mRNA measurements were performed in triplicate and normalized to an internal control of GAPDH. After the PCR program, data were analyzed with ABI 7300 SDS software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Western blot analysis

The rat penile samples were lysed in RIPA buffer (1×TBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.004% sodium azide, 10 μl/ml PMSF, 10 μl/ml protease inhibitor cocktail, 10 μl/ml sodium orthovanadate). Protein concentration was measured using the Coomassie Plus Protein Assay Reagent™ (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Equal quantities (30 μg) of lysates were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate gradient polyacrylamide gels and electro-blotted onto PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The membranes were blocked and then incubated with rabbit anti-IGFBP-3 antibody (Sc-9028) at 1:1000 dilutions (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Chemiluminescence was detected using ECL Western blotting detection reagents (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). The expression of IGFBP-3 protein was visualized by densitometry using the Mivnt Image analysis system (Shanghai Institute of Optical Instruments, Shanghai, China).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The measurement of serum testosterone concentration in penile tissue was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testosterone detection kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Similarly the measurement of cGMP concentration in penile tissue was performed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) cGMP detection kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ±SD. Differences among normal control group, diabetic control group, and IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group were considered significant at the level of p<0.05 using the 2-tailed unpaired t test.

Results

Evaluation of erectile function

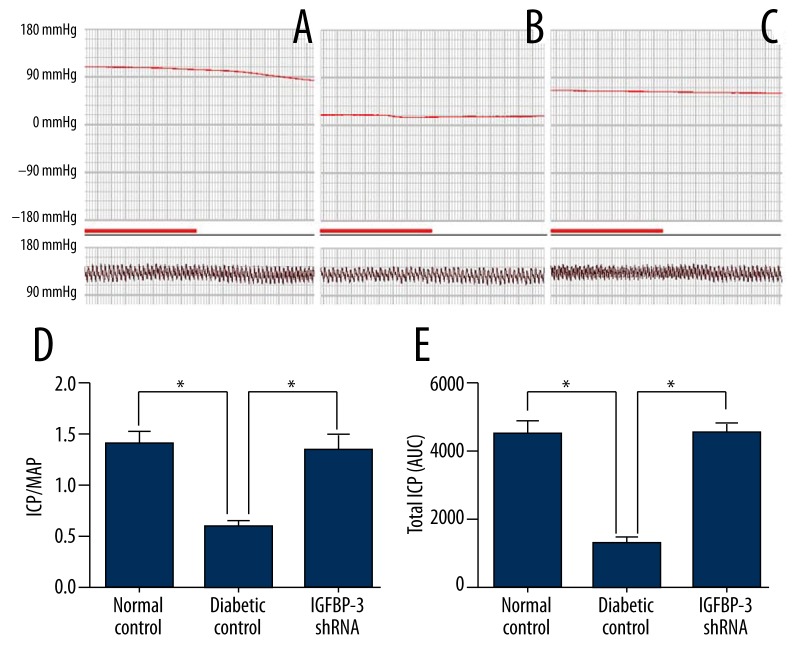

We determined the ratio of ICP/MAP and the total ICP (area under curve) during electrostimulation of the cavernous nerves at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA administration. The representative ICP tracing in response to electrostimulation of the cavernous nerves is shown in Figure 1(A–C). Electrostimulation elicited significantly increased ICP/MAP ratio (Figure 1D) and total ICP (Figure 1E) in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group compared to those in the diabetic control group (p<0.01, respectively). These data suggest that IGFBP-3 shRNA administration rehabilitated erectile function in diabetic rats.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of erectile function. Representative ICP responses to cavernous nerves electrical stimulation at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment in the normal control group (A), diabetic control group (B) (n=9), and IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group (C). The bold line indicates 1 min of electrical stimulation to the cavernous nerves. The data on ICP/MAP (D) and total ICP (the area under curve) (E) were collected from 9 rats in each group. * p<0.01, compared to diabetic control. MAP: mean arterial pressure; ICP: intracavernous pressure.

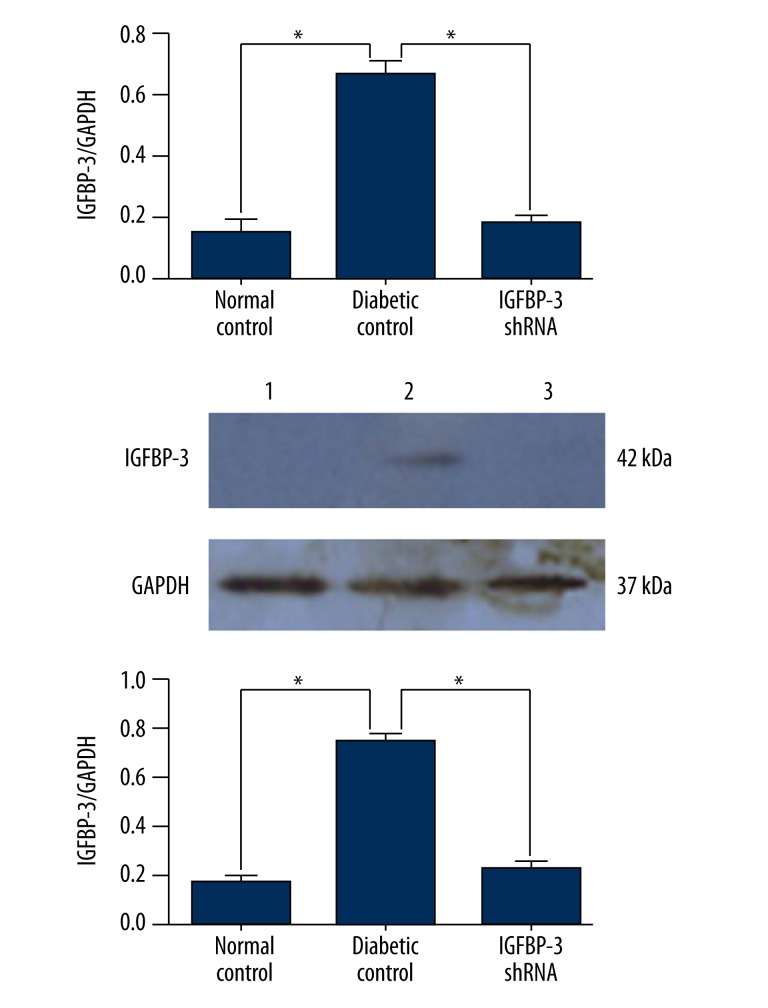

IGFBP-3 shRNA inhibits IGFBP-3 expression in rat cavernous tissue

Real-time qPCR analysis using GAPDH as a housekeeping gene showed that cavernous IGFBP-3 mRNA level in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group was significantly lower than in the diabetic control group (P<0.01, Figure 2). Accordingly, Western blot analysis showed that cavernous IGFBP-3 protein level in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group was significantly lower than in the diabetic control group (P<0.01, Figure 3, lower). These results are consistent with the results of real-time qPCR analysis and prove that IGFBP-3 shRNA inhibits IGFBP-3 expression in rat cavernous tissue.

Figure 2.

IGFBP-3 shRNA inhibits IGFBP-3 mRNA and protein expression in rat cavernous tissue. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of IGFBP-3 mRNA level in rat cavernous tissue at 12 weeks after intracavernous administration of IGFBP-3 shRNA. Western blot analysis of IGFBP-3 protein level in rat cavernous tissue of normal control (lane 1), diabetic control (lane 2), and IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group (lane 3) at 12 weeks after intracavernous administration of IGFBP-3 shRNA. The data were collected from 9 rats in each group. * P<0.01, compared to diabetic control, respectively.

Figure 3.

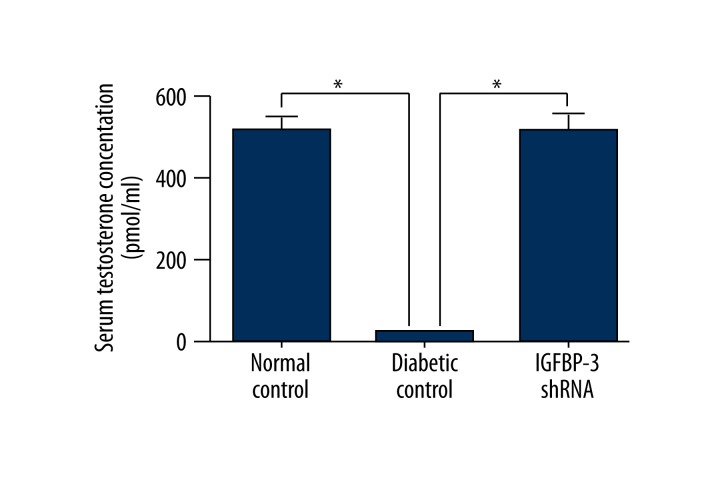

Testosterone concentrations in rat serum. Testosterone concentrations in rat serum at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment were determined by ELISA. The data were collected from 9 rats in each group. * p<0.01, compared to diabetic control.

Testosterone and cGMP concentrations in rat serum

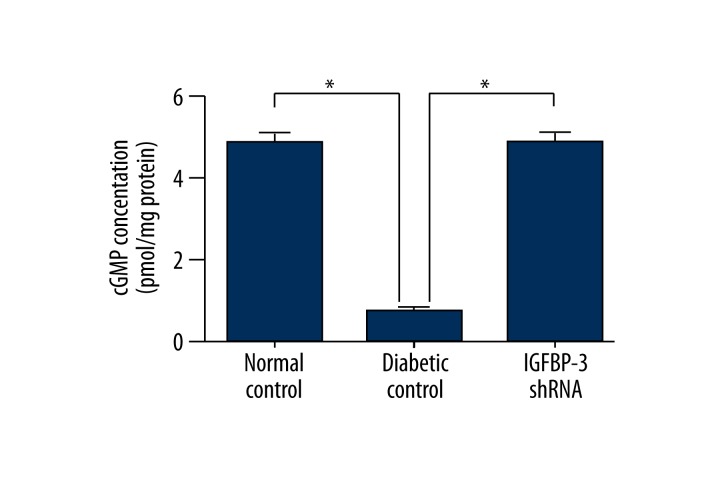

Both serum testosterone and cavernous cGMP concentrations were measured by ELISA and we found that serum testosterone and cavernous cGMP concentrations were both significantly increased in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group compared to those in the diabetic control group at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA administration (p<0.01, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

cGMP concentrations in rat cavernous tissue. cGMP concentrations in rat penile tissue at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment were determined by ELISA. The data were collected from 9 rats in each group. * p<0.01, compared to diabetic control.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that concentration of serum testosterone was significantly higher in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group compared to that in the diabetic control group (p<0.01) at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA administration. These results suggest that IGFBP-3 shRNA may rehabilitate erectile function via increases of concentrations of serum testosterone and cavernous cGMP in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

The possibility that hypogonadism might contribute to diabetes mellitus (DM)-related ED has been reconsidered recently, because of a higher prevalence of low testosterone in diabetic than in nondiabetic individuals [10–12], and even in animal models of chemical diabetes, overt hypogonadism is often reported [4,13].

Essentially, androgens play a dual role in the erectile process by controlling both pro-erectile and anti-erectile signaling pathways [14,15]. On the one hand, androgens exert a positive role in the maintenance of the general architecture of the penile contractile structure. Castration induces cavernous smooth muscle atrophy and contributes to structural alteration of erectile tissue, with a relative increase in connective tissue content [16–18]. Furthermore, castration reduced nitric oxide (NO) and its generating enzyme NO synthase (NOS), as well as NOS-containing nerve fibers [19]. Thus, in castrated rats, erectile response is markedly impaired, but testosterone (T) reverses this deficiency [16,17]. A recent study reported that testosterone may prevent impaired erectile function by maintaining at the control level the expression of the key enzymes involved in the erectile process, such as nNOS [20]. On the other hand, it has been recently demonstrated that androgens up-regulate the major mechanism responsible for cGMP degradation, phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) [19], and PDE5 regulates the amount of cGMP available for cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation and penile erection. A clinical report demonstrated a null effect of hypogonadism on penile erection [21], probably because androgen reduction produces both decreased cGMP formation (effect on NO) and degradation (effect on PDE5) [20]. The major subcellular mechanism by which erection occurs involves NO-induced activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and increased cGMP concentration [22]. A significantly decreased level of cGMP in diabetes rats was associated with ED in our previous study [23]. Here, we found that serum testosterone and cavernous cGMP concentrations were both significantly increased in the IGFBP-3 shRNA treatment group compared to those in the diabetic control group at 12 weeks after IGFBP-3 shRNA administration These results suggest that IGFBP-3 shRNA may rehabilitate erectile function via increased concentration of serum testosterone and improvement of NO-cGMP signaling activities in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

IGFBP-3, conventionally thought to inhibit growth through ligand sequestration, might also be antiproliferative and proapoptotic through actions independent of the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor [19,24]. A previous study has shown that IGFBP-3 is significantly correlated with erectile function in the diabetic rat model [25]. The increased expression of IGFBP-3 might lead to depletion of the smooth muscle density and elicit ED in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) [26]. Since IGFBP expression is suppressed by androgens, an increase of concentration of serum testosterone might decrease the expression of IGFBP-3 (the most abundant IGFBP) [7]. Thus, hyperglycemia in combination with increased IGFBP-3 expression may have a role in the development of ED [5].

Conclusions

The current study indicated that IGFBP-3 shRNA may rehabilitate erectile function via increased concentration of serum testosterone and improvement of NO-cGMP signaling activities in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Further investigation of the mechanisms by which increased concentration of serum testosterone leads to activation of NO-cGMP signaling will enrich our understanding of the pathogenesis of ED of STZ-induced diabetic rats.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of support: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30872572) and Hubei Province’s Outstanding Medical Academic Leader Program

References

- 1.Ponholzer A, Temml C, Mock K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in 2869 men using a validated questionnaire. Eur Urol. 2005;47(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mesples A, Majeed N, Zhang Y, et al. Early immunotherapy using autologous adult stem cells reversed the effect of anti-pancreatic islets in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus: Preliminary results. Med Sci Monit. 2013;19:852–57. doi: 10.12659/MSM.889525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang XH, Filippi S, Morelli A, et al. Testosterone restores diabetes-induced erectile dysfunction and sildenafil responsiveness in two distinct animal models of chemical diabetes. J Sex Med. 2006;3(2):253–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang XH, Morelli A, Luconi M, et al. Testosterone regulates PDE5 expression and in vivo responsiveness to tadalafil in rat corpus cavernosum. Eur Urol. 2005;47(3):409–16. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soh J, Katsuyama M, Ushijima S, et al. Localization of increased insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in diabetic rat penis: implications for erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2007;70:1019–23. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang Z, Zhou Z, Wang X, et al. Short hairpin ribonucleic acid constructs targeting insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 ameliorates diabetes mellitus-related erectile dysfunction in rats. Urology. 2013;81(2):464 e11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moschos SJ, Mantzoros CS. The role of the IGF system in cancer: From basic to clinical studies and clinical applications. Oncology. 2002;63:317–32. doi: 10.1159/000066230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magee TR, Kovanecz I, Davila HH, et al. Antisense and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) constructs targeting PIN (Protein Inhibitor of NOS) ameliorate aging-related erectile dysfunction in the rat. J Sex Med. 2007;4:633–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pu XY, Wang XH, Gao WC, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 restores erectile function in aged rats: modulation the integrity of smooth muscle and nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling activity. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1345–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corona G, Mannucci E, Mansani R, et al. Organic, relational and psychological factors in erectile dysfunction in men with diabetes mellitus. Eur Urol. 2004;46(2):222–28. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corona G, Mannucci E, Petrone L, et al. Association of hypogonadism and type II diabetes in men attending an outpatient erectile dysfunction clinic. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18(2):190–97. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corona G, Mannucci E, Schulman C, et al. Psychobiologic correlates of the metabolic syndrome and associated sexual dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2006;50(3):595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballester J, Munoz MC, Dominguez J, et al. Insulin-dependent diabetes affects testicular function by FSH- and LH-linked mechanisms. J Androl. 2004;25(5):706–19. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2004.tb02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maggi M, Filippi S, Ledda F, et al. Erectile dysfunction: from biochemical pharmacology to advances in medical therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;143:143–54. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1430143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morelli A, Filippi S, Mancina R, et al. Androgens regulate phosphodiesterase type 5 expression and functional activity in corpora cavernosa. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2253–63. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shabsigh R. The effects of testosterone on the cavernous tissue and erectile function. World J Urol. 1997;15:21–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01275152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aversa A, Isidori AM, Greco EA, et al. Hormonal supplementation and erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2004;45:535–38. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traish AM, Park K, Dhir V, et al. Effects of castration and androgen replacement on erectile function in a rabbit model. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1861–68. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Firth SM, Baxter RC. Cellular actions of the insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:824–54. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vignozzi L, Morelli A, Filippi S, et al. Testosterone regulates RhoA/Rho-kinase signaling in two distinct animal models of chemical diabetes. J Sex Med. 2007;4(3):620–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corona G, Mannucci E, Mansani R, et al. Aging and pathogenesis of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(5):395–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghalayini IF. Nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway with some emphasis on cavernosal contractility. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(6):459–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Z, Zhou Z, Wang X, et al. Short Hairpin Ribonucleic Acid Constructs Targeting Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein-3 Ameliorates Diabetes Mellitus-related Erectile Dysfunction in Rats. Urology. 2013;81:464.e11–464.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Minder C, et al. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3, and cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1346–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdelbaky TM, Brock GB, Huynh H. Improvement of erectile function in diabetic rats by insulin: possible role of the insulin-like growth factor system. Endocrinology. 1998;139(7):3143–47. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Lin CS, Spencer EM, Lue TF. Insulin-like growth factor-I promotes proliferation and migration of cavernous smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280(5):1307–15. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]