Abstract

Objectives

To identify cognitive predictors of geriatric depression treatment outcome.

Method

Older participants completed baseline measures of memory and executive function, health, and baseline and posttreatment Hamilton Depression Scales (HAM-D) in a 12-week trial comparing psychotherapies (problem-solving vs. supportive; n = 46). We examined cognitive predictors to identify treatment responders, i.e., HAM-D scores reduced by ≥50%, and remitters, i.e., posttreatment HAM-D score ≤ 10.

Results

Empirically-derived decision trees identified poorer performance on switching (i.e. Trails B), with a cut-score of ≥82” predicting psychotherapy responders. No other cognitive or health variables predicted psychotherapy outcomes in the decision trees.

Conclusions

Psychotherapies that support or improve the executive skill of switching may augment treatment response for older patients exhibiting executive dysfunction in depression. If replicated, Trails B has potential as a brief cognitive tool for clinical decision-making in geriatric depression.

Mood disorders, particularly major depressive disorder, afflict 2.6% of older Americans (1) and are associated with cognitive impairment, particularly executive dysfunction (2). The ubiquity of acute and persistent cognitive deficits in late-life depression and the high rate of treatment resistant depression among older patients has led to concern regarding the negative impact of cognitive deficits on treatment outcome (3). Problem solving therapy (PST), a behavioral intervention adapted to target depression in older individuals with executive dysfunction demonstrates efficacy in these patients (4). In addition, supportive therapy (ST), a person-centered psychological intervention, shows efficacy for late-life depression with executive function deficits, but to a lesser degree than PST (4).

It is imperative for geriatric clinicians to identify older patients who may have a better response to psychological treatments for depression and those requiring more intensive or qualitatively different treatment approaches. Previous studies have derived useful clinical decision-making trees that identified factors such as early treatment response and other psychiatric symptoms to predict posttreatment response in older patients with depression enrolled in pharmacotherapy (5). Using this same approach, we investigated baseline cognitive abilities as predictors of posttreatment response and remission of late-life depression in a psychotherapy trial (6).

Method

The current study examined data from a subset of participants selected to complete baseline neuropsychological tests in a previously described 12-week randomized control trial for late-life depression. Psychotherapy (PST and ST) in the Collaborative Psychotherapy study for Executive Dysfunction and Depression (COPED) (6) COPED was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). All participants provided their written informed consent.

Selection criteria and measures for the trial are described elsewhere (6). In brief, participants were 60 or older and met criteria for Major Depression as established by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (7). The study excluded individuals with the following histories: substance use disorders, bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, dementia or a positive screen for dementia. The trial also excluded individuals currently enrolled in psychotherapy or antidepressant treatment; at high risk for suicide; with an Axis I disorder other than unipolar depression and generalized anxiety disorder; current use of drugs known to cause depression; history of head trauma; and current acute and severe medical illness. The study measured depression from baseline to 12-weeks with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; 8). Forty-nine participants randomized to psychotherapy (ST or PST) were selected to complete additional neuropsychological testing than was done in the parent trial. Three partipants were missing HAM-D scores at week 12, leaving a total of 46 participants.

Participants completed measures of mental and physical health (The Quality Metric Short Form 36-item Health Survey; SF-36; 9), learning and memory (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised or HVLT-R; 10) and executive functioning. Executive functioning measures assessed abstract reasoning (Wisconsin Card Sorting Task; 11), attention (Trail Making Test; TMT, Part A; 12), switching (TMT, Part B; 12), and verbal fluency (Controlled Oral Word Association Test; 13 and animal naming; 14).

Statistical Analysis

We derived decision trees to identify cognitive and therapeutic predictors of treatment response and remission for psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy using signal detection software for Receiver Operator Characteristics (15, 16, 17). The software examines multiple predictor variables of a single outcome variable using an iterative analysis. This produces a hierarchical output of subgroups based on empirically derived cut-scores with the best sensitivity and specificity for detecting the target outcome using a p-value of 0.01. The process repeats, resulting in additional subgroups until predictors are no longer significant. We defined treatment response as a 50% or more decrease in the 25-item HAM-D total score from baseline to post-treatment (yes/no), and treatment remission as a total score of 10 or less on the 25-item HAM-D at post-treatment (yes/no). A post-hoc analysis examined whether predictors of remission remained significant using more stringent definition of remission based on recent studies (HAM-D total score of 6 or less). Baseline variables examined as predictors of response and remission in the ROC analyses included: demographic (age, sex, education, ethnicity), treatment type (PST vs. ST or nortriptyline vs. paroxetine), depression (HAM-D), health (SF-36 mental and physical health functioning), and cognition (memory and executive functioning).

Results

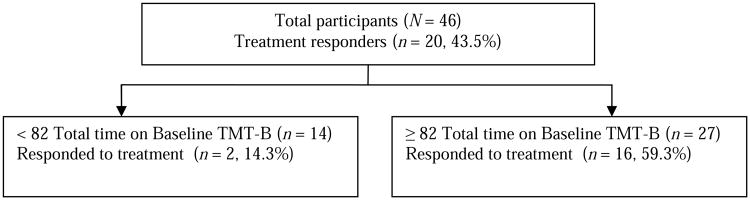

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of participants in the treatment trial. Figure 1 shows the clinical decision tree generated from the ROC analyes.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 46 older participants enrolled in psychological treatment for depression, M (±SD) or N (%).

| Participant Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age in Years | 70.78 (7.3) |

| Education in Years | 15.78 (2.5) |

| Female Sex | 30 (65.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 3 (6.5) |

| Asian | 5 (10.9) |

| Black | 5 (10.9) |

| Pacific Islander/Hawaiian | 1 (2.2) |

| White | 32 (69.6) |

| Mental Health (SF-36) | 33.10 (9.4) |

| Physical Health (SF-36) | 41.16 (12.3) |

| Memory (HVLT; # of words) | 7.27 (3.3) |

| Executive Functioning | |

| Animal fluency (Animals; # of words) | 16.41 (5.4) |

| Letter fluency (COWAT; # of words) | 36.85 (14.3) |

| Attention (TMT-A; time in sec) | 46.83 (24.3) |

| Shifting (TMT-B; time in sec) | 125.90 (68.8) |

| Abstract reasoning (WCST; # of categories) | 1.83 (1.6) |

| Depression Severity (HAM-D) | |

| Baseline | 22.54 (2.7) |

| 12-week | 12.76 (6.1) |

Note: SF-36 = The Quality Metric Short Form 36-item Health Survey; HVLT = Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised; Animals = Animal Naming task; COWAT = Controlled Oral Word Association Test; TMT-A = Trail Making Test, Part A; TMT-B = Trail Making Test, Part B; WCST= Wisconsin Card Sorting Task; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Scale. SF-36 Mental and Physical Health component summary scores have a possible range of 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher functioning. Due to missing data, the sample size for the HVLT = 45 and for the TMT-A, TMT-B, WCST = 41.

Figure 1. Clinical Decision Tree for Psychotherapy Treatment Response by week 12.

Note: TMT-B = Trail Making Test, Part B; Treatment responders were classified as having a 50% or greater decrease in baseline total score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression by week 12. A total of 43.5% responded to treatment by week 12. A total time of 82 seconds or greater, indicative of worse performance on the TMT-B at baseline predicted a 59.3% chance of responding to treatment. The total sample with a completed TMT- B was 41 due to missing data.

Clinical Decision Trees of Treatment Response and Remission

A cut-score of 82 seconds on the TMT Part B provided the best clinical validity for detecting psychotherapy treatment response for late-life depression, χ2(40) = 7.57, p < .01 (see Figure 1). Specifically, worse performance using the empirically derived cut-score of ≥ 82 on the TMT, Part B detected 16 treatment responders, or 59.3%, of the 27 participants who obtained this score, whereas only 2 out of 14, or 14.3%, of those scoring < 82 on the TMT, Part B responded to treatment. No additional variables, such as psychotherapy type (PST or ST) or the other cognitive measures, emerged as predictors of response in the decision tree at the p < 0.01 level. No decision tree was computed for psychotherapy remission by week 12 because none of baseline predictor variables were significant at the level of p < 0.01. The software, however, identified a cut-score of ≥ 82 on the TMT, Part B as predictive of increased likelihood of remission in psychotherapy in 13 out of 27 cases, χ2(1) = 4.56, p < 0.05. This finding was no longer significant in a post-hoc analyses using a more stringent definition of remission (HAM-D score ≤ 6), χ2(1) = 0.00, NS.

ROC Sensitivity and Specificity for the Empirically Derived Cut-Scores

A cut-score of 82 on the TMT, Part B offered good sensitivity but poor specificity for detection of psychotherapy treatment response and remission (see Table 2).

Table 2. Validity for the Empircally Derived Cut-scores for Psychotherapy Treatment Response and Remission.

| Cut-Score | Sens | CI | Spec | CI | PPV | CI | NPV | CI | Kappa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | ||||||||||

| TMT-B ≥ 82** | 0.89 | 0.79 – 0.98 | 0.54 | 0.39 – 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.44 – 0.74 | 0.93 | 0.85 – 1.01 | 0.39 | |

| Remission | ||||||||||

| TMT-B ≥ 82* | 0.87 | 0.76 – 0.97 | 0.46 | 0.31 – 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.33 – 0.63 | 0.86 | 0.75 – 0.96 | 0.28 |

Note: Sens = Sensitivity. CI = 95% Confidence Interval. Spec = Specificity. PPV = Positive Predictive Value. NPV = Negative Predictive Value. TMT-B = Trail Making Test, Part B time in seconds. df = 1;

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05.

Discussion

This investigation suggests that poorer baseline executive functioning in switching ability may predict treatment response to psychological interventions for late-life depression. Notably, the type of psychological treatment (PST vs. ST) and other demographic and cognitive variables were not reliable predictors of psychological treatment response or remission. It has been hypothesized that executive dysfunction is part of late-life depression syndrome (18); these executive problems may in fact drive depression in some older adults. This study suggests that interventions that either do not rely heavily on executive control (e.g., Supportive Therapy) or are focused on improving executive function (e.g., PST), may be particularly suited for patients with executive dysfunction. The fact that a cognitive flexibility task (TMT, Part B) was more predictive of outcomes than other executive tests (i.e., WCST, COWAT) suggests that people who have trouble shifting their attention between two simultaneous tasks may reap the greater benefit from these therapies.

This finding is in line with recent work which found that reduced activation of prefrontal brain regions during set shifting predicted response to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (19). Our findings are also in line with a recent investigation of behavioral predictors in late-life depression, which found performance on the Stroop Color and Word Test measure of speed-of-processing and inhibitory mechanisms improved following PST and that improved performance was associated with a significant reduction in depressive symptoms post PST (20). Together, these studies implicate a core attentional/inhibitory deficit as a significant predictor of positive response to psychotherapies for late-life depression. If our findings are further confirmed in other studies, a cut-score of 82 seconds on the Trail Making Test, Part B could potentially inform clinical decision making by providing a brief cognitive tool to identify older patients needing more structure and cognitive support in psychological treatment for depression. Albeit not a predictor in the empirically-derived decision tree, psychotherapy remission was also associated with this same cut-score on this task suggesting this cut-score is potentially meaningful and useful to predict both response and remission in older patients with depression.

Limitations

Although the results from this study are suggestive, they also should be interpreted with caution, largely because of the small sample sizes. This study is indeed an exploratory one, that provides potential targets and hypotheses for future research studies. The sensitivity of detecting treatment response using this cut-score was good, but it should be noted that specificity was poor. Further, the cut-score detected for treatment remission was no longer significant using a more stringent threshold for defining remission. Thus, the exploration of which executive tasks should be used in treatment decision-making still requires confirmation.

In summary, executive functioning as measured by set-shifting might offer a useful clinical tool to match older patients with depression to psychotherapy. These patients might benefit from highly structured and less cognitively intensive psychological treatments to support executive abilities that are impaired and interwined with depressive symptoms. Our findings are intriguing in light of research implicating executive dysfunction as part of late-life depressive syndromes.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms. Claudine Catledge for her assistance with data management in support of this study. The UCSF study was funded by MH074717 (PI: Arean).

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gum AM, King-Kallimanis B, Kohn R. Prevalence of mood, anxiety, and substance-abuse disorders for older Americans in the national comorbidity survey-replication. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:769–81. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ad4f5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butters MA, Whyte EM, Nebes RD, et al. The nature and determinants of neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:587–95. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Kanellopoulos D, et al. Problem solving therapy for the depression-executive dysfunction syndrome of late life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:782–8. doi: 10.1002/gps.1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexopoulos GS, Raue PJ, Arean PA. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreescu C, Mulsant BH, Houck PR, et al. Empirically derived decision trees for the treatment of late-life depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:855–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arean PA, Raue P, Mackin RS, et al. Problem-solving therapy and supportive therapy in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1391–98. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams MB, Janet BW, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M. Biometrics Research. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2007. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Clinical Trials Version (SCID-CT) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), I: conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt J, Benedict RHB. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised. Odessa, Fla.: PAR; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lineweaver TT, Bond MW, Thomas RG, Salmon DP. A normative study of Nelson's (1976) modified version of the Wisonsin Card Sorting Test in healthy older adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;13:328–47. doi: 10.1076/clin.13.3.328.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neurpsychological Test Battery: Therapy and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, Ariz: Neuropsychological Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benton AL, Hamsher K, Sivan AB. Multilingual aphasia examination. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller RB, Dobbs AR. Age differences in word finding in discourse and nondiscourse situations. Psychology and Aging. 1993;8:443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Hara R, Thompson JM, Kraemer HC, et al. Which Alzheimer patients are at risk for rapid cognitive decline? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002 Winter;15(4):233–8. doi: 10.1177/089198870201500409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yesavage JA, Jo B, Adamson MM, et al. Initial cognitive performance predicts longitudinal aviator performance. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(4):444–53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraemer HC. Evaluating medical tests: objective and quantitative guidelines. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. Vascular depression hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:915–22. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallagher Thompson D, Kessler SR, Sudheimer K, et al. fMRI activation during executive function predicts response to cognitive behavioral therapy in older, depressed adults. Amer J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;15:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackin RS, Nelson JC, Delucchi K, et al. Cognitive outcomes after psychotherapeutic interventions for major depression in older adults with executive dysfunction. Amer J Geriatr Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.11.002. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]