Abstract

Background & Aims

Fewer than 20% of patients with cirrhosis undergo surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), so these tumors are often detected at late stages. Although primary care providers (PCPs) follow 60% of patients with cirrhosis in the US, little is known about their practice patterns for HCC surveillance. We investigated factors associated with adherence to guidelines for HCC surveillance by PCPs.

Methods

We conducted a web-based survey of all 131 PCPs at a large urban hospital. The survey was derived from validated surveys and pretested among providers; it included questions about provider and practice characteristics, self-reported rates of surveillance, surveillance test and frequency preference, and attitudes and barriers to HCC surveillance.

Results

We obtained a clinic-level response rate of 100% and provider-level response rate of 60%. Only 65% of respondents reported annual and 15% reported biannual surveillance of patients for HCC. Barriers to HCC surveillance included not being up-to-date with HCC guidelines (68% of PCPs), difficulties in communicating effectively with patients about HCC surveillance (56%), and more important issues to manage in clinic (52%). About half of PCPs (52%) reported using ultrasound or measurements of α-fetoprotein in surveillance; 96% said that this combination was effective in reducing HCC-related mortality. However, many providers incorrectly believed that clinical examination (45%), or levels of liver enzymes (59%) or α-fetoprotein alone (89%), were effective surveillance tools.

Conclusions

PCPs have misconceptions about tests to detect HCC that contribute to ineffective surveillance. Reported barriers to surveillance include suboptimal knowledge about guidelines, indicating a need for interventions, including provider education, to increase HCC surveillance effectiveness.

Keywords: AFP, screening, liver cancer, early detection

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and has an increasing incidence in the United States1. Prognosis for patients with HCC depends on tumor stage at diagnosis, with curative options only available for patients diagnosed at an early stage2. Patients with early HCC achieve 5-year survival rates near 70% with resection and transplantation, whereas those with advanced HCC have a median survival of less than one year3, 4.

HCC surveillance has been demonstrated to improve early detection and survival in patients with hepatitis B infection5. Although there is not a randomized controlled trial in patients with cirrhosis, HCC surveillance is associated with early tumor detection, receipt of curative treatments, and improved survival in several cohort studies6. Based on this evidence, several societies, including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), recommend surveillance using ultrasound, with or without AFP, at six-month intervals in patients with cirrhosis7. Although surveillance is efficacious for detecting HCC at an early stage8, its effectiveness in clinical practice is impacted by several factors, including low utilization rates9-11. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that fewer than 20% of patients with cirrhosis in the United States undergo surveillance12. Rates of guideline-consistent surveillance every 6 months are even lower at less than 5%. Although there are multiple potential reasons for surveillance underutilization, provider recommendation is one of the strongest predictors for receipt of HCC surveillance13.

Currently, primary care providers (PCPs) follow most patients with cirrhosis in the United States, with only 20-40% being followed by gastroenterologists/hepatologists14. By recommending HCC surveillance to their patients, PCPs play a central role in implementing guidelines. Low surveillance rates may relate to poor provider knowledge or negative attitudes regarding the benefits of surveillance. However, data on PCP knowledge, attitudes, and practice patterns regarding HCC surveillance are sparse. An understanding of these attitudes and barriers can facilitate the development and implementation of interventions to improve HCC surveillance effectiveness. The aim of our study was to explore provider- and practice-level factors associated with guideline-consistent recommendations for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis.

METHODS

Study Population

The Parkland Health and Hospital System (Parkland), the safety net health system of Dallas County, includes a network of 12 primary care clinics and cares for over 2000 patients with cirrhosis. Eligible respondents were any PCP who reported seeing at least one patient with cirrhosis per week. We selected providers practicing the primary care specialties of general practice, family practice, and general internal medicine. We excluded providers who were in residency training, retired, or those whose major professional activity was teaching, research, or administration. Overall, we sampled 131 PCPs from this safety net health system. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Survey Development and Administration

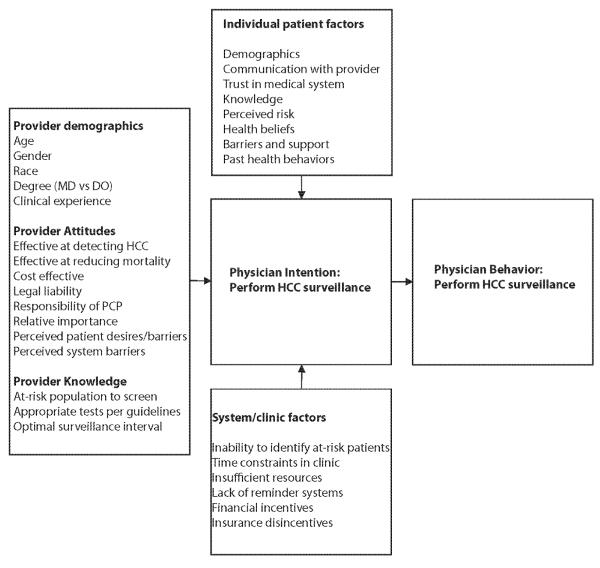

Eligible physicians were sent an anonymous web-based survey between August 2012 and March 2013. Providers who did not respond to the initial survey were sent a follow-up web-based survey and given an opportunity to complete the survey at a PCP clinic meeting. The survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete and included questions about self-reported surveillance rates, surveillance test and frequency preference, attitudes and barriers to HCC surveillance, and provider and practice characteristics. We used a theoretical model of physician behavior (Figure 1), based on Social Cognitive Theory15 and the Theory of Reasoned Action16, to guide selection of relevant physician and practice variables. This model includes domains of provider background and experience, perceptions of screening, physician influences, and practice environment and practice patterns. As it has been successfully applied to colorectal cancer screening17, we hypothesized that these factors would be associated with guideline-consistent HCC surveillance recommendations. Questions were adapted from earlier validated surveys when available18-21. After initial development of the survey, it was pretested among 10 providers, with each provider completing a cognitive interview about the survey after completion22, 23.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model for Primary Care Provider HCC Surveillance Recommendations

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

Our primary outcome of interest was guideline-consistent HCC surveillance recommendations based on AASLD guidelines7, 24. This outcome was assessed in two independent manners. First, providers were asked to provide self-reported annual and biannual surveillance rates for patients with cirrhosis. Second, providers were provided six patient vignettes and asked if they would recommend HCC surveillance. Potential surveillance choices included ultrasound alone, AFP alone, ultrasound and AFP, CT and/or MRI, and no surveillance. Four cases warranted HCC surveillance, whereas two cases did not necessitate surveillance. Surveillance recommendations were categorized into three possibilities: overuse, underuse, and appropriate use (i.e. guideline-consistent). Secondary outcome of interests were provider-reported surveillance test choice (ultrasound alone, AFP alone, ultrasound and AFP, CT and/or MRI, or no surveillance) and surveillance interval (every 3 months, every 6 months, every 12 months, or other).

Distributions of provider characteristics and perceptions of screening were reported with descriptive statistics. Fisher exact and Mann-Whitney rank-sum tests were performed to identify factors associated with guideline-consistent HCC surveillance recommendations for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Independent variables included perceived test effectiveness and influence of factors such as guidelines, financial reimbursement, practice patterns of colleagues, and patient preferences. We assessed potential barriers to surveillance including difficulty in identifying patients with liver disease and/or cirrhosis, time constraints in clinic, lack of patient interest, difficulty communicating with patients, poor patient compliance, and a shortage of facilities to provide HCC surveillance. Physician and practice demographics included age, gender, race and ethnicity, number of years in practice, provider type, and number of patients seen during a typical week. Statistical significance was defined as p-value less than 0.05. All data analysis was performed using Stata 11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Provider and Clinic Characteristics

We had a provider-level response rate of 59% (n=77 of 131 providers) and clinic-level response rate of 100% (n=12 of 12 clinics). Provider characteristics are provided in Table 1. Nearly one-third (30%) of providers were over age 50, 60% between 35-50 years old, and 10% were younger than 35 years old. The majority (56%) of providers were female. Most providers (90%) were board certified in Internal Medicine or Family Practice and 63% were full-time clinical faculty. All respondents routinely cared for patients with cirrhosis, with 50% seeing more than 10 patients per year.

Table 1.

Primary Care Provider and Practice Characteristics

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (% Male) | 29 (44.0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity Non-Hispanic Caucasian Black Asian Hispanic Caucasian |

19 (28.8%) 8 (12.1%) 30 (45.5%) 4 (6.1%) |

| Primary Clinic Practice Location Hospital-based clinic Outpatient Clinic |

22 (33.8%) 43 (66.2%) |

| Type of Practitioner MD, internal medicine MD, family practice MD, not board certified Mid-level provider (NP or PA) |

38 (55.9%) 23 (33.8%) 2 (2.9%) 4 (5.9%) |

| Years in Practice Less than 10 years 11 - 25 years More than 25 years |

6 (9.8%) 37 (60.7%) 18 (29.5%) |

| Time Spent on Patient Care (%) Less than 50% 50-80% Greater than 75% |

12 (17.7%) 13 (19.1%) 43 (63.2%) |

| Number patients per week Fewer than 25 patients 26 - 50 patients 51 - 75 patients More than 75 patients |

14 (18.4%) 16 (21.1%) 21 (27.6%) 25 (32.9%) |

| Number patients with cirrhosis per year Fewer than 10 patients 11 - 25 patients 26 - 50 patients More than 50 patients |

38 (50.0%) 22 (29.0%) 11 (14.5%) 5 (6.5%) |

Approximately two-thirds of the providers reported their primary practice location was in PHHS community-oriented primary care (COPC) clinics, whereas the other one-third practiced in hospital-based clinics. Although 78% of providers reported having systems-level reminders, such as computer-based prompts, for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, none reported similar reminder systems for HCC surveillance. As expected, providers reporting seeing a racially and socioeconomically diverse cohort of patients. Over 40% of providers reported the majority of their patients were African American and/or Hispanic. Similarly, nearly 50% of providers reported the majority of their patients were uninsured and only covered by Parkland Health Plus, a healthcare assistance program for Dallas County residents.

Provider Attitudes and Barriers Regarding HCC Surveillance

Provider attitudes are detailed in Table 2. Most PCPs believed HCC surveillance is effective for early tumor detection (85%) and cost-effective (79%); however only half (52%) believed it reduces all-cause mortality. Nearly all (96%) providers reported ultrasound +/− AFP are effective HCC surveillance tests. However, providers incorrectly believed clinical exam (45%), liver enzyme testing (59%), and AFP alone (89%) are also effective HCC surveillance tests. Despite a lack of evidence, 92% of providers believed CT and/or MRI are also effective as HCC surveillance tests.

Table 2.

Primary Care Provider Attitudes regarding HCC Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis

| Attitude regarding HCC Surveillance | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of HCC surveillance for early stage tumor detection Strongly agree Agree Disagree Strongly disagree |

16 (21.6%) 47 (63.5%) 9 (12.2%) 2 (2.7%) |

| Effectiveness of HCC surveillance for reducing mortality Strongly agree Agree Disagree Strongly disagree |

8 (11.0%) 30 (41.1%) 29 (39.7%) 6 (8.2%) |

| Cost-effectiveness of HCC surveillance Strongly agree Agree Disagree Strongly disagree |

25 (34.2%) 33 (45.2%) 14 (19.2%) 1 (1.4%) |

| Provider legally liability if not performing HCC surveillance Strongly agree Agree Disagree Strongly disagree |

6 (8.1%) 22 (29.7%) 29 (39.2%) 17 (23.0%) |

| Providers responsibility for HCC surveillance Primary care provider alone Both primary care provider and gastroenterologist Gastroenterologist alone |

4 (5.3%) 68 (89.4%) 4 (5.3%) |

Providers reported several influential factors including evidence in published literature (93%), out-of-pocket costs to patients (82%), and practice patterns of colleagues (70%). Many providers reported a positive influence from AASLD (64%) and NCCN (54%) guidelines on their surveillance practices; however, 87% reported being less likely to perform surveillance given a lack of US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations. Interestingly, one-fourth of providers (26%) reported patient preferences are not important in determining their HCC surveillance recommendations. Only 38% of providers were concerned about potential legal ramifications for not performing HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis.

Most PCPs (90%) reported HCC surveillance is the responsibility of both PCPs and gastroenterologists, and only 5% believed it is the responsibility of gastroenterologists alone. However, providers reported several barriers to performing HCC surveillance, including not being up to date with current guidelines (68%), difficulty with effective communication with patients about HCC surveillance (56%), and having more important issues to manage in clinic (52%) (Table 3). Other potential issues such as identifying the at-risk population (36%) and radiologic capacity (23%) were not perceived as major barriers to surveillance. Providers also expressed little concern about patient barriers to effective surveillance. Two-thirds (66%) of respondents believed patients with cirrhosis want to discuss HCC surveillance and less than 10% were concerned about patient non-compliance when ordering surveillance.

Table 3.

Primary Care Provider Reported Barriers to Effective HCC Surveillance

| Barriers to Effective HCC Surveillance | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Insufficient time in clinic Often Sometimes Rare to never |

9 (13.8%) 18 (27.7%) 38 (58.5%) |

| Competing interests in clinic Often Sometimes Rare to never |

10 (15.2%) 24 (36.4%) 32 (48.4%) |

| Not being up-to-date with surveillance guidelines Often Sometimes Rare to never |

12 (18.2%) 33 (50%) 21 (31.8%) |

| Difficulty identifying at-risk population Often Sometimes Rare to never |

5 (7.7%) 18 (27.7%) 42 (64.6%) |

| Insufficient radiologic capacity Often Sometimes Rare to never |

6 (9.2%) 9 (13.8%) 50 (76.9%) |

| Difficulty arranging follow-up diagnostic testing for patients Often Sometimes Rare to never |

14 (21.5%) 14 (21.5%) 37 (57.0%) |

| Difficulty arranging treatment for patients with HCC Often Sometimes Rare to never |

11 (15.5%) 23 (32.4%) 37 (52.1%) |

| Difficulty communicating with patients Often Sometimes Rare to never |

4 (6.3%) 32 (50%) 28 (43.7%) |

| Patients are not interested in discussing HCC surveillance Often Sometimes Rare to never |

6 (9.2%) 16 (24.6%) 43 (66.2%) |

| Concerns about patient non-compliance Often Sometimes Rare to never |

2 (3.1%) 4 (6.2%) 59 (90.7%) |

Provider Surveillance Practices

Self-reported surveillance rates

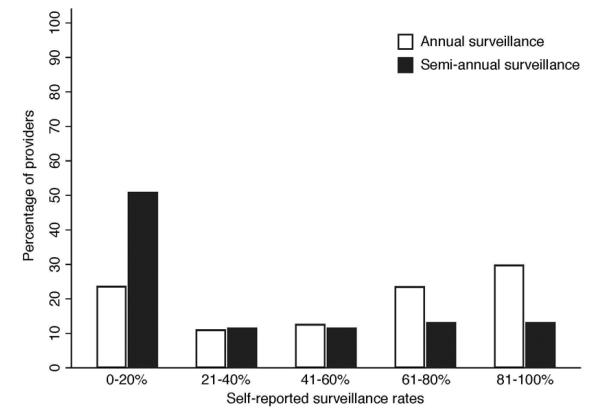

Providers had median self-reported annual ultrasound surveillance rates of 65% (range 0-100%) in patients with cirrhosis (Figure 2), although median biannual surveillance rates were only 15% (range 0-100%). Gender and provider type were associated with self-reported annual surveillance rates. Female providers reported significantly higher HCC surveillance rates than males (75% vs. 45%, p=0.04), and mid-level providers reportedly higher surveillance rates than other providers (85% vs. 55%, p=0.03).

Figure 2.

Primary Care Provider Self-Reported HCC Surveillance Recommendations

Patient clinical vignettes

We also assessed guideline-consistent HCC surveillance recommendations using six clinical vignettes (Supplemental Table). Although 83% of providers would perform ultrasound-based surveillance in 50-year old patients with compensated cirrhosis, reported rates were lower in patients with ascites (68%), those with morbid obesity (63%), and otherwise healthy elderly patients (50%). Nearly one-fifth of providers would instead perform surveillance with CT and/or MRI in those with ascites (19%) and those with morbid obesity (22%). The only predictor of surveillance underuse in clinical vignettes was a belief that ultrasound and AFP were not effective at reducing HCC-related mortality (p=0.04).

With regard to surveillance overuse, many providers would perform surveillance in patients with non-cirrhotic hepatitis C infection (77%) and those with significant comorbid conditions precluding any survival benefit (55%). In fact, 53% of respondents felt that HCC surveillance was cost-effective in patients with non-cirrhotic hepatitis C.

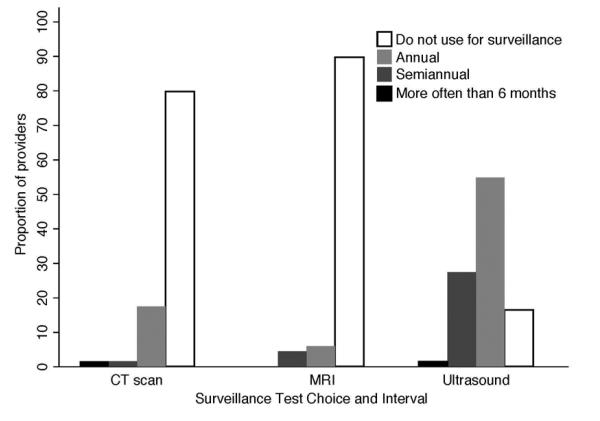

Test Choice and Surveillance Interval

Most (83%) PCPs reported using ultrasound, with or without AFP, for surveillance in patients with cirrhosis seen in clinic, although one-fourth (20-30%) of providers reported also using CT and/or MRI for surveillance (Figure 3). Providers were more likely to use ultrasound-based surveillance if they believed ultrasound and AFP were effective at reducing mortality in cirrhosis (p=0.003), did not overuse surveillance in those without cirrhosis (p=0.002), reported their practice patterns were influenced by published literature (p=0.04) or patient preference (p=0.04), and were interested in CME activities about HCC surveillance (p=0.04). Two-thirds of providers who use ultrasound-based surveillance do so on an annual basis, and only one-third reported performing surveillance every 6 months (Figure 3). One-fourth (25%) of providers reported an increased frequency of ultrasound use over the past few years, although most (62%) reported no change in their ultrasound use.

Figure 3.

Primary Care Provider Surveillance Test Choice and Interval

DISCUSSION

Given the growing literature highlighting the underuse of HCC surveillance in clinical practice, a better understanding of provider knowledge and attitudes is needed. Most prior surveys were conducted among gastroenterologists and/or focused on HBV patients25-27, and there are few studies evaluating PCP attitudes and practice patterns for HCC surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Our study fills an important void in current literature given PCPs follow over 60% of patients with cirrhosis nationally. We found over 90% of PCPs believe HCC surveillance is their responsibility; however, they have misconceptions about how best to perform surveillance and report several barriers to effective implementation. These findings highlight the need for provider education and systems-level interventions to optimize HCC surveillance effectiveness in clinical practice.

A key finding of our study is that several HCC surveillance recommendations and practices reported by PCPs were inconsistent with current guidelines. Nearly 90% of providers believed AFP is an effective surveillance test when used alone, and two-thirds of providers reported performing annual, instead of biannual, surveillance. This is consistent with studies highlighting misconceptions among providers caring for chronic hepatitis B patients, in whom many providers use liver enzymes and HBV viral load as HCC surveillance tests26. The choice of surveillance tests and intervals from our study also reflect practice patterns seen in SEER, in which many patients receive inconsistent surveillance using AFP alone28. The use of inappropriate surveillance tests and intervals is concerning given that poor test sensitivity is an important reason for late stage tumor detection in clinical practice29. Biannual surveillance significantly increases sensitivity for detecting tumors at an early stage, when curative options exist, compared to annual surveillance30. Similarly, surveillance with AFP alone is not recommended given poor sensitivity and specificity when used in isolation31.

The majority of PCPs reported believing CT and MRI were effective as HCC surveillance tests, and one-fourth of providers reported using CT/MRI intermittently as surveillance tests in their patients. This is consistent with other reports suggesting these tests are increasingly being used for surveillance purposes, particularly in liver transplant centers. However, the one study evaluating cross-sectional imaging found annual CT was marginally less sensitive (67% vs. 71%) and more costly for detection of early HCC than biannual ultrasound32. Similarly, three-fourths of providers reported performing surveillance in patients with HCV but no cirrhosis. Although surveillance may be reasonable in some patients with stage 3 fibrosis given the possibility of sampling error on biopsy, this would account for the minority of noncirrhotic patients. Overall, this cohort remains at low risk for HCC and surveillance is not cost-effective in those without cirrhosis. Studies are needed to further assess the magnitude and potential harms of surveillance overuse in those without cirrhosis.

Although most PCPs believe HCC surveillance is at least partly their responsibility, we were unable to determine how providers believe this responsibility should be shared between PCPs and gastroenterologists. In fact, this may contribute to underuse of surveillance if both providers assume the other will order the appropriate testing. Furthermore, they reported several barriers to implementation, including not being up-to-date with current guidelines and having more important issues to manage in clinic. These barriers are similar to those reported by providers for other cancer-screening efforts, such as CRC screening33, 34. Lessons learned from other cancers can likely be applied to optimize HCC surveillance uptake in clinical practice35. In CRC screening, provider-focused reminders and systematic mass screening programs have been successful strategies to bypass or increase provider recommendations for screening; however, similar interventions have yet to be attempted for HCC surveillance among patients with cirrhosis36. In our study, three-fourths of providers reported systems-level reminders, such as computer-based prompts, for CRC screening, none reported similar reminder systems for HCC surveillance.

Many providers reported difficulty with effective communication with patients about HCC surveillance and one-fourth reported not accounting for patient preferences when considering HCC surveillance. In an age where patient involvement is being increasingly recognized as being important, this finding is both surprising and concerning. Patients with cirrhosis have high levels of concern regarding HCC, desire information about HCC surveillance from their providers, and want to be more involved in their care37. Furthermore, involvement of patients in their care has been previously shown to be an independent predictor of HCC surveillance completion37. Patient communication and engagement should be considered as an important target for future interventions to optimize surveillance rates.

It is important to note that our study had limitations. Our study was performed in a single large safety-net hospital and may not be generalized to other practice settings. For example, our results might not be generalizable to PCPs associated with transplant centers given most patients in our center are not eligible for liver transplantation given social and/or financial barriers38. However, most PCPs at Parkland are well aware of our large multidisciplinary HCC clinic, which evaluates all patients with HCC for treatment (including liver transplantation as applicable)39. A national survey is needed to see if our data are representative of PCPs practicing in other settings. Additionally, surveillance rates were self-reported and may not reflect actual practice. Survey studies are inherently limited by response bias, in which respondents answer questions how they should practice instead of how they actually practice. Although we had a high provider-lever response rate of 59% and clinic-level response rate of 100%, there is also the possibility of non-response bias, in which providers who routinely perform surveillance are more likely to respond.

Overall, our study provides important insights into PCP knowledge, attitudes and barriers regarding HCC surveillance among patients with cirrhosis. Despite over 90% of PCPs believing HCC surveillance is their responsibility, they have misconceptions about how best to perform surveillance and report several barriers to implementation. These misconceptions and barriers might partly explain the gap between the efficacy of HCC surveillance and its effectiveness in clinical practice. Overall, these findings highlight the need for provider education and systems-level interventions to optimize HCC surveillance effectiveness in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table: Survey Clinical Vignettes

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was conducted with support from UT-STAR, NIH/NCATS Grant UL1-TR000451, and the ACG Junior Faculty Development Award awarded to Dr. Singal. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of UT-STAR, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and its affiliated academic and health care centers, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose

Author Contributions:

Eimile Dalton-Fitzgerald – acquisition of data and drafting of manuscript

Jasmin Tiro – study concept, administrative support, and design and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content

Pragathi Kandunoori – acquisition of data

Ethan A. Halm – study concept, administrative support, and design and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content

Adam Yopp – interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content

Amit G. Singal – study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content, obtained funding, and study supervision.

REFERENCES

- 1.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singal AG, Marrero JA. Recent advances in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:189–95. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283383ca5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, Vilana R, Ayuso Mdel C, Sala M, Bru C, Rodes J, Bruix J. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang BH, Yang BH, Tang ZY. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:417–22. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singal AG, Pillai A, Tiro J. Early Detection, Curative Treatment, and Survival Rates for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Update. Hepatology. 2010;53:1–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, Salgia R, Higgins P, Rogers MA, Marrero JA. Meta-analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:37–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, Kanwal F, Richardson PA, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:85–93. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-2-201101180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singal AG, Conjeevaram HS, Volk ML, Fu S, Fontana RJ, Askari F, Su GL, Lok AS, Marrero JA. Effectiveness of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:793–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singal AG, Marrero JA, Yopp A. Screening process failures for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:375–82. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singal AG, Yopp A, C SS, Packer M, Lee WM, Tiro JA. Utilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:861–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singal AG, Yopp AC, Gupta S, Skinner CS, Halm EA, Okolo E, Nehra M, Lee WM, Marrero JA, Tiro JA. Failure Rates in the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance Process. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:1124–1130. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanyal A, Poklepovic A, Moyneur E, Barghout V. Population-based risk factors and resource utilization for HCC: US perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:2183–91. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.506375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michels TC, Taplin SM, Carter WB, Kugler JP. Barriers to screening: the theory of reasoned action applied to mammography use in a military beneficiary population. Mil Med. 1995;160:431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yabroff KR, Klabunde CN, Yuan G, McNeel TS, Brown ML, Casciotti D, Buckman DW, Taplin S. Are physicians’ recommendations for colorectal cancer screening guideline-consistent? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:177–84. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1516-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klabunde CN, Jones E, Brown ML, Davis WW. Colorectal cancer screening with double-contrast barium enema: a national survey of diagnostic radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1419–27. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.6.1791419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, Jones E, Nadel M, Vernon SW. A national survey of primary care physicians’ colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med. 2003;36:352–62. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, Breen N, Seeff LC, Brown ML. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43:939–44. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nadel MR, Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Seeff LC, Uhler R, Smith RA, Ransohoff DF. A national survey of primary care physicians’ methods for screening for fecal occult blood. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:86–94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beatty P, Willis G. Research synthesis: the practice of cognitive interviewing. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2007;71:287–311. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willis G. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–36. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalasani N, Said A, Ness R, Hoen H, Lumeng L. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis in the United States: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2224–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khalili M, Guy J, Yu A, Li A, Diamond-Smith N, Stewart S, Chen M, Jr., Nguyen T. Hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma screening among Asian Americans: survey of safety net healthcare providers. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1516–23. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1439-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saab S, Nguyen S, Ibrahim A, Vierling JM, Tong MJ. Management of patients with cirrhosis in Southern California: results of a practitioner survey. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:156–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000196189.65167.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, Du XL, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:132–41. doi: 10.1002/hep.23615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singal AG, Nehra M, Adams-Huet B, Yopp AC, Tiro JA, Marrero JA, Lok AS, Lee WM. Detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at advanced stages among patients in the HALT-C trial: where did surveillance fail? Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:425–32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trevisani F, De NS, Rapaccini G, Farinati F, Benvegnu L, Zoli M, Grazi GL, Del PP, Di N, Bernardi M. Semiannual and annual surveillance of cirrhotic patients for hepatocellular carcinoma: effects on cancer stage and patient survival (Italian experience) Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:734–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta S, Bent S, Kohlwes J. Test characteristics of alpha-fetoprotein for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C. A systematic review and critical analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:46–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-1-200307010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pocha C, Dieperink E, McMaken KA, Knott A, Thuras P, Ho SB. Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer with ultrasonography vs. computed tomography -- a randomised study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:303–12. doi: 10.1111/apt.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlandi MA. Promoting health and preventing disease in health care settings: an analysis of barriers. Prev Med. 1987;16:119–30. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pommerenke FA, Dietrich A. Improving and maintaining preventive services. Part 1: Applying the patient path model. J Fam Pract. 1992;34:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singal AG, Tiro JA, Gupta S. Improving hepatocellular carcinoma screening: applying lessons from colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:472–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levin TR, Jamieson L, Burley DA, Reyes J, Oehrli M, Caldwell C. Organized colorectal cancer screening in integrated health care systems. Epidemiol Rev. 2011;33:101–10. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singal A, Volk M, Rakoski M, Fu S, Su G, McCurdy H, Marrero J. Patient Involvement is Correlated with Higher HCC Surveillance in Patients with Cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:727–732. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820989d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singal AG, Chan V, Getachew Y, Guerrero R, Reisch JS, Cuthbert JA. Predictors of liver transplant eligibility for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a safety net hospital. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:580–6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, Arenas J, Trimmer C, Reddick M, Pedrosa I, Khatri G, Yakoo T, Meyer JJ, Shaw J, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Establishment of a Multidisciplinary Hepatocellular Carcinoma Clinic is Associated with Improved Clinical Outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1287–95. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table: Survey Clinical Vignettes