Abstract

Objectives

To assess the prevalence of awareness and use of massive open online courses (MOOCs) among medical undergraduates in Egypt as a developing country, as well as identifying the limitations and satisfaction of using these courses.

Design

A multicentre, cross-sectional study using a web-based, pilot-tested and self-administered questionnaire.

Settings

Ten out of 19 randomly selected medical schools in Egypt.

Participants

2700 undergraduate medical students were randomly selected, with an equal allocation of participants in each university and each study year.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were the percentages of students who knew about MOOCs, students who enrolled and students who obtained a certificate. Secondary outcome measures included the limitations and satisfaction of using MOOCs through five-point Likert scale questions.

Results

Of 2527 eligible students, 2106 completed the questionnaire (response rate 83.3%). Of these students, 456 (21.7%) knew the term MOOCs or websites providing these courses. Out of the latter, 136 (29.8%) students had enrolled in at least one course, but only 25 (18.4%) had completed courses earning certificates. Clinical year students showed significantly higher rates of knowledge (p=0.009) and enrolment (p<0.001) than academic year students. The primary reasons for the failure of completion of courses included lack of time (105; 77.2%) and slow Internet speed (73; 53.7%). Regarding the 25 students who completed courses, 21 (84%) were satisfied with the overall experience. However, there was less satisfaction regarding student–instructor (8; 32%) and student–student (5; 20%) interactions.

Conclusions

About one-fifth of Egyptian medical undergraduates have heard about MOOCs with only about 6.5% actively enrolled in courses. Students who actively participated showed a positive attitude towards the experience, but better time-management skills and faster Internet connection speeds are required. Further studies are needed to survey the enrolled students for a better understanding of their experience.

Keywords: Computer-Assisted Instruction , Medical Education , Distance Education , MOOCs, Egypt

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to assess the prevalence of awareness and use of massive open online courses (MOOCs) among medical students in Egypt.

This study includes a large representative sample of 10 Egyptian institutions covering nearly the entire geographic area of Egypt.

Data are obtained from students in all six undergraduate years.

There was a relatively low number of respondents who enrolled or successfully completed a MOOC, which makes the analysis of limitations and satisfaction less reliable.

The study results cannot be generalised to all developing countries.

Introduction

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) have recently been proposed as a disruptive innovation, with high expectations to meet challenges facing higher education.1 The idea behind MOOCs is to offer world-class education to a (massive) number of students around the globe with Internet access (online) for low, or no fees (open). The courses consist of pre-recorded video lectures, computer-graded tests and discussion forums to review course materials or to get help.2 These courses have gained immense popularity over a short period of time, attracting millions of participants and crossing the barriers of location, gender, race and social status; making 2012 the year of MOOCs according to the New York Times.3 In its latest infograph in October 2013, Coursera (which is the largest MOOCs provider) demonstrated an extraordinary growth, reaching more than 100 institutional partners, offering more than 500 courses and enrolling more than five million students.4

In medical education, the number of related MOOCs is steadily increasing. In a recent study, it was found that 98 free courses were offered during 2013 in the fields of health and medicine, with an average length of 6.7 weeks.5 These courses were introduced as a possible solution to the great challenges facing medical education.6 These challenges include the issue of quality, cost and the ability to deliver education to an adequate number of students to cover the healthcare system's needs.7 Nowadays, there are ongoing discussions aimed at determining the role of MOOCs in medical education. However, information about how medical students perceive such courses is still limited, especially in developing countries where high-quality learning is often scarce.

MOOCs are considered as a solution to providing developing countries with high-quality education. However, the current demographic data reveals that most of the MOOCs’ participants are from developed countries, with very low participation rates from low-income countries, especially in Africa.4 This low participation rate was thought to be due to various complicated conditions, such as the lack of access to digital technology, linguistic and cultural barriers and poor computer skills.8 In addition, the lack of awareness of this newly-introduced concept may be considered to be another problem.

To our knowledge, there are no available cross-sectional studies that have assessed the awareness and use of MOOCs among medical communities in developing countries, including Egypt. Our study primarily aims to assess the prevalence of awareness and use of these courses among undergraduate medical students in Egypt, as an example of a developing country. Second, our study aims to assess the limitations that hinder students from enrolling in and completing the courses, as well as assessing the satisfaction level of using MOOCs to better understand the role these courses play in medical education.

Methodology

This is a multicentre, cross-sectional study using a structured, web-based, pilot-tested and self-administered questionnaire.

Study population and sample

Our target population was undergraduate medical students across Egypt, enrolled in 19 medical schools during the 2013–2014 academic year. We selected 10 out of the 19 medical schools to be our study settings using a simple random sampling technique. Selected institutions included Ain Shams, Al-Azhar medical school in Cairo, and medical schools in Alexandria, Assiut, Benha, Beni Suef, Cairo, Menoufia, Suez Canal and Tanta.

Students in these schools were enrolled in a 6-year MBBCh programme, in which the first 3 years are called academic years and the last 3 years are called clinical years. To achieve a 99% CI, 3% margin of error and 50% response distribution, 1784 students were required to represent the study population. We used a stratified simple random technique to select our sample with an equal allocation of participants in each university and in each study year. Accordingly, using the registered students’ names lists, we randomly selected 270 students from each faculty (45 for each study year) for a total of 2700 participants. We excluded non-Egyptian students and those who changed their enrolment school at the time of data collection.

Data collection

Selected participants were invited by email and social media websites to participate in our survey using a unique code for each participant during the period of March–April 2014. In each university, a team of data collectors were recruited (two active members from each class), which was led by a local study coordinator (LSC). This team received standardised training on how to approach selected students either online or offline. Each LSC was responsible for obtaining the students lists for each class through official channels. The two principle investigators selected the students randomly from these lists according to the planned sampling technique. Initially, participants from two universities were invited using their official emails. However, there was a very low response rate as many students do not check their emails regularly, which is partially explained by the fact that this email service was not introduced into Egyptian universities until recently. Therefore, we shifted our data collection plan to the use of social media websites (mainly Facebook). The majority of Egyptian medical students have Facebook accounts, and each class has a Facebook group, including all students of that class, for study-related discussions. The two data collectors of each class were responsible for obtaining the personal account of each selected student. To confirm that the collected account belonged to the selected student, a personal message was sent first to this account to confirm his or her personal details. After receiving the confirmation, a Facebook message was sent containing a cover letter with the study's aims, the participant's special code and a link to the online questionnaire. The student was to first fill out a voluntary consent form after reading the study aims and instructions. We sent up to five reminder messages to participants, prompting them to complete the survey. If we did not get a response in two to 3 weeks, non-responders were approached in lecture rooms and training sessions to ask them to complete the questionnaire. If any of them informed us of a lack of Internet access, and if the respondent agreed to partricipate, a paper version of the questionnaire (same questions and format as the online version) was provided for immediate completion. LSCs were responsible for entering the data into our online system. We used an online survey program to administer the questionnaire (Survey Gizmo; Boulder, Colorado, USA).

Questionnaire Development

The study questionnaire was developed by the research team through group discussions after an extensive literature review. The draft was then reviewed by two experts in the fields of medical education and biostatistics. The questionnaire was then piloted on 175 students, from all participating medical schools. Detailed feedback about the format, clarity and completion time was collected and used to make minor changes. We did not include the pilot responses in our analysis.

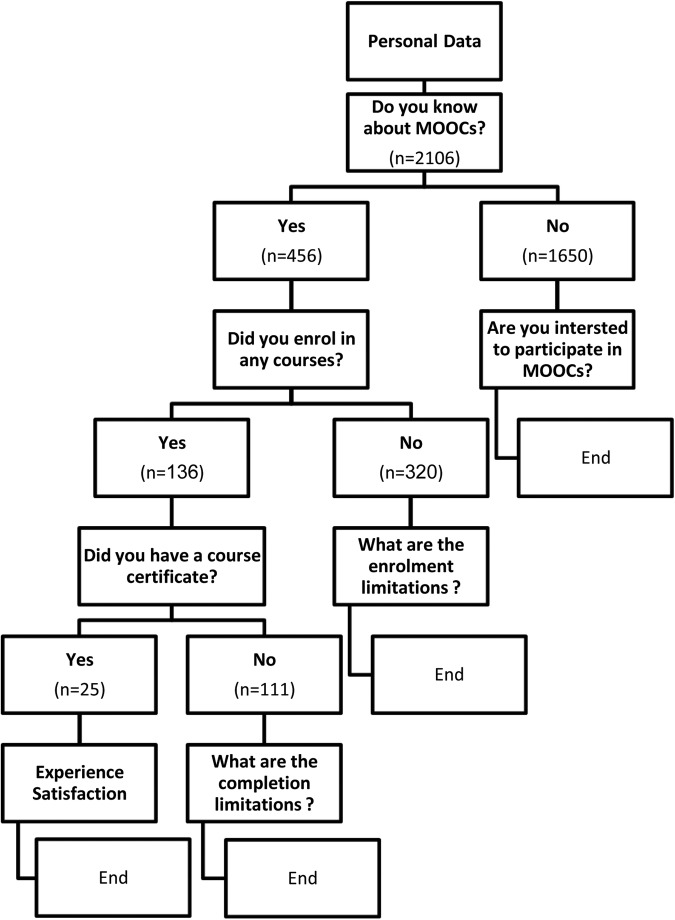

The questionnaire was in Arabic, the participants’ native language, and it included 29 questions in four sections using a branching logic function (figure 1). The first section addressed study aims, consent and participants’ personal information. This section was followed by a main question asking if the student had heard about the new open online educational system (MOOCs) provided in websites, including Coursra, Edx, Udacity and FutureLearn, among others. Based on his or her answer, the participant was directed to different sections. Students who knew about MOOCs were asked how they heard about it and their state of enrolment. If the participant was not enrolled in any course, respondents were asked about the limitations to their use and then the questionnaire ended.

Figure 1.

Questionnaire branching logic questions and the number of responders to each one.

Enrolled students were directed to the next section, which assessed their perspectives and experiences with MOOCs. For students who gained certificates, further questions were asked regarding their level of satisfaction as well as any obstacles they might have faced. Finally, four questions were asked to assess students’ opinions about the integration of MOOCs into the medical field.

Most of the questions were in a single-answer multiple-choice format. However, there were three multiselection check-box questions. For the assessment of limitations, satisfaction and opinions, a five-point Likert scale between one (strongly agree/satisfied) and five (strongly disagree/unsatisfied) was used.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as numbers and percentages with the CI at 99%. The significance of the association between qualitative variables of interest was analysed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests, as indicated. To focus on clear opinions, the five-point Likert scale of limitations, satisfaction and opinions was collapsed into three categories (agree/satisfied, neutral and disagree/unsatisfied). Class year was recoded as a dichotomous variable in order to compare results for students in academic versus clinical education. The acknowledgment of the importance of getting a certificate before enrolment was also recoded as a dichotomous variable (important/very important vs limited importance/not important). This was to test the significance of association between the primarily reported importance of acquiring a certificate and the actual possession of the certificate by McNemar test. All tests were bilateral and a p value of 0.01 was used as the limit of statistical significance. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS statistical software package V.22.

Results

Respondent characteristics

Of 2700 total participants, 62 (2.3%) were excluded for being non-Egyptians or having changed their enrolment school, in addition to 111 (4.1%) students who could not be reached, resulting in a final eligible cohort of 2527 students. During the data collection phase, 2357 (93.3%) online questionnaire invitations and 170 (6.7%) paper versions were sent out. Out of these distributed questionnaires, 2106 responses were received (response rate 83.3%). Table 1 shows participants’ demographics regarding school, class and gender.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and their state of knowledge, enrolment and certificate attainment

| Knowledge about MOOCs |

p Value | Enrolment in courses |

p Value | Certificate attainment |

p Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%) (n=2106) |

Yes (%) (n=456) |

No (%) (n=1650) |

Total (n=456) |

Yes (%) (n=136) |

No (%) (n=320) |

Total (n=136) |

Yes (%) (n=25) |

No (%) (n=111) |

||||

| Faculty | ||||||||||||

| Ain shams | 207 (9.8) | 38 (18.4) | 169 (81.6) | 0.04 | 38 | 13 (34.2) | 25 (65.8) | 0.13 | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | 0.02 |

| Al-azhar | 216 (10.3) | 42 (19.4) | 174 (80.6) | 42 | 11 (26.2) | 31 (73.8) | 11 | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Alexandria | 222 (10.5) | 48 (21.6) | 174 (78.4) | 48 | 19 (39.6) | 29 (60.4) | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | |||

| Assuit | 180 (8.5) | 33 (18.3) | 147 (81.7) | 33 | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) | 6 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | |||

| Benha | 205 (9.7) | 57 (27.8) | 148 (72.2) | 57 | 16 (28.1) | 41 (71.9) | 16 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (100.0) | |||

| Beni Suef | 220 (10.4) | 38 (17.3) | 182 (82.7) | 38 | 6 (15.8) | 32 (84.2) | 6 | 0 (0.0) | 6 (100.0) | |||

| Cairo | 188 (8.9) | 39 (20.7) | 149 (79.3) | 39 | 12 (30.8) | 27 (69.2) | 12 | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | |||

| Menoufia | 248 (11.8) | 53 (21.4) | 195 (78.6) | 53 | 22 (41.5) | 31 (58.5) | 22 | 10 (45.5) | 12 (54.5) | |||

| Suez Canal | 199 (9.4) | 59 (29.6) | 140 (70.4) | 59 | 20 (33.9) | 39 (66.1) | 20 | 2 (10.0) | 18 (90.0) | |||

| Tanta | 221 (10.5) | 49 (22.2) | 172 (77.8) | 49 | 11 (22.4) | 38 (77.6) | 11 | 1 (9.1) | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Class | ||||||||||||

| Academic | 1076 (51.2) | 176 (16.4) | 900 (82.6) | <0.001 | 176 | 40 (22.7) | 136 (77.3) | 0.01 | 40 | 4 (10.0) | 36 (90.0) | 0.1 |

| Clinical | 1024 (48.8) | 280 (27.3) | 744 (72.7) | 280 | 96 (34.3) | 184 (65.7) | 96 | 21 (21.9) | 75 (78.1) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 926 (44.1) | 199 (21.4) | 730 (78.6) | 0.83 | 199 | 71 (35.7) | 128 (64.3) | 0.02 | 71 | 17 (23.9) | 54 (76.1) | 0.08 |

| Female | 1174 (55.9) | 257 (21.8) | 920 (78.2) | 257 | 65 (25.3) | 192 (74.7) | 65 | 8 (12.3) | 57 (87.7) | |||

Knowledge about MOOCs

We found that 456 (21.7% (99% CI 19.4% to 24%)) students had heard about MOOCs or websites providing such courses. There was no statistically significant difference in knowledge between males and females (43.6% vs 56.4%, 99 CI p=0.8). However, clinical year students had higher rates of knowledge than students in the academic years (p<0.001; table 1). Additionally, there was no difference between medical schools in the students’ knowledge about MOOCs (p=0.04).

After informing the students who did not know about MOOCs that this system provides scientific courses in different disciplines given by specialists from top universities worldwide for no or low fees through the Internet, 1342 (81.3% (99% CI 78.8% to 83.8%)) students showed an interest in participating with a significant difference among different medical schools (p<0.001).

Enrolment and certificate attainment

Of those who knew about MOOCs, 136 (29.8% (99% CI 24.3% to 35.3%)) were enrolled in at least one course. Most students (125; 91.9%) registered in 1–5 courses, with 113 (83.1%) students reporting having watched at least one video lecture. Home (109; 99%) was the primary place where they watched these videos. There was no statistically significant difference in enrolment between males and females (52.2% vs 47.8%, 99% CI p=0.016). However, there was a significant difference between students’ class and their enrolment (p=0.009; table 1). Coursera was the most commonly used website (99; 72.8%), followed by Edx (14; 10.3%).

Only 25 students (18.4% (99% CI 9.8% to 26.9%)) completed courses and attained one certificate or more with an 81.6% dropout rate. Interestingly, more than half the students who earned certificates (13; 52% (99% CI 26.3% to 77.7%)) have used the signature track to obtain verified certificates from the universities that offered the courses. The vast majority of enrolled students stated that getting a certificate was important to them (32 (23.5%) very important, 37 (27.2%) important, 50 (36.8%) important to some extent and 17 (12.5%) not important). Out of the 69 students who assumed that getting a certificate is important before enrolment (important/very important), 17 (24.6%) were finally certified, as compared to only 8 (11.6%) certified students out of the 67 who were not concerned about receiving a certificate at the time of enrolment (important to some extent/not important; 11.9%); p<0.001.

Ways of knowledge and students’ motivations

To assess how students found out about MOOCs and what their motivations were, two multiselection questions were asked. Social media was the primary way through which 206 (45.2%) students were introduced to MOOCs, while knowledge through a friend was the second (184; 40.4%). Web-search engines (87; 19.1%) took the third place, followed by extracurricular activities (46; 10.1%). MOOC providers’ advertisements played a very small role (27; 5.9%) in reaching students as did the official websites of medical schools (15; 3.3%). Notably, there was no association between the method through which students learnt about MOOCs and their enrolment. Nevertheless, students who were introduced through extracurricular activities were found to enrol more frequently (p=0.005).

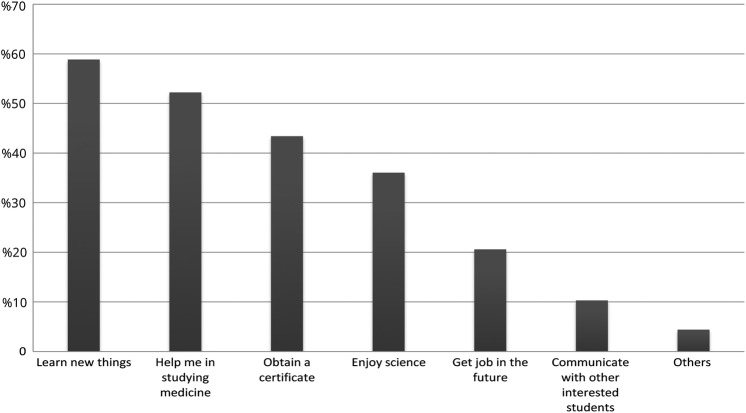

Concerning students’ motives, most students reported that their main motivation was “to learn new things” followed by “to help me study medicine” (figure 2). Interestingly, the students who enrolled aiming to have a certificate or to help them in obtaining a future job were significantly more likely to complete the courses (p=0.001 and p=0.008, respectively).

Figure 2.

Student's motives for enrolment in massive open online courses (MOOC's) reported by 136 students.

MOOCs and medicine

By asking the enrolled students (n=136) about their experience and attitude toward medical MOOCs, 103 (75.7% (99% CI 66.2% to 85.2%)) declared participation in at least one medical course. Of them, 24 students (17.6% (99% CI 7.9% to 27.3%)) had completed medical courses and earned certificates. Regarding their medical MOOC experience, 102 (75%) students agreed that MOOCs helped them in developing their theoretical background about the topic discussed. However, there was less agreement (68; 50%) on the role of MOOCs in developing their practical skills. Most students (89; 65.4%) agreed that MOOCs helped in studying medicine, while 83 (61%) believed that MOOCs will help them in securing a more desirable, better job opportunity in the future.

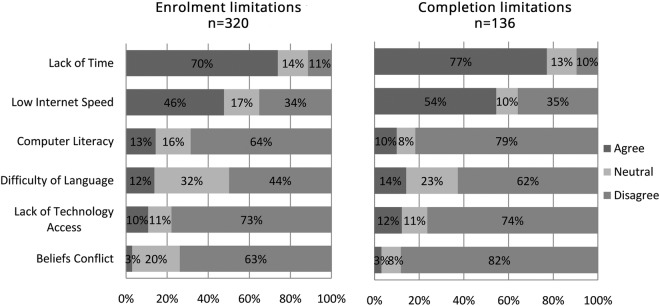

Limitations of MOOCs

Our study reported two types of limitations: enrolment and completion. Students who knew about MOOCs, but did not enrol in any courses (n=320) were asked about their enrolment limitations. The majority of students (226; 70.6%) agreed that a lack of time was the main limitation, while 147 (45.9%) agreed that slow Internet speed was another cause (figure 3). Enrolled students (n=136) were asked to assess the limitations that made them drop out of courses. Similar to the enrolment limitations, lack of time (105; 77.2%) and slow Internet speed (73; 53.7%) were the main obstacles. Lack of technology access, computer literacy, language difficulty and culture conflicts were less frequently selected as a limiting factor to completion of the course (figure 3). Only 16 (11.8%) students agreed that the scientific content was difficult for them to comprehend. In addition, 93 (68.4%) students disagreed that ‘lower content than expected’ was a limitation.

Figure 3.

Enrolment and completion limitations.

For further assessment of Internet speed, we asked the enrolled students to rate their Internet speed. Sixty students (44.1%) reported that the speed was reasonable, while 55 (40.4%) reported slow speed, and only 21 (15.4%) had a high connection speed. When we compared the students’ evaluation of Internet speed and determined whether they watched video lectures, we did not find a significant association (p=0.69).

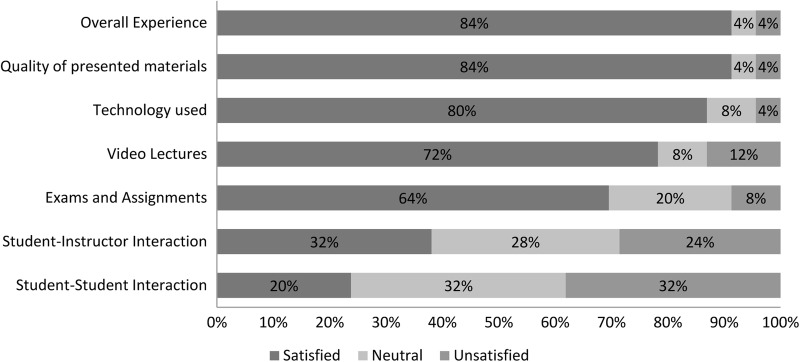

Students’ satisfaction of MOOCs

The 25 students who obtained certificates were asked to report their opinions about each part of the MOOCs experience. The results showed that most students (21; 84%) were satisfied with the overall experience, including video lectures (18; 72%), exams and assignments (16; 64%), quality of the presented materials (21; 84%) and the technology used (20; 80%). However, there was less satisfaction regarding student–student (5; 20%) and student–instructor (8; 32%) interactions (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Student satisfaction regarding massive open online courses (MOOC's) experience.

Discussion

Available information regarding MOOC participants is primarily data obtained from course-end demographics, which usually demonstrate a heterogeneous population of varying age groups, educational levels and countries globally. These data show that most MOOC users are well-educated males with low participation from developing countries, and undergraduates.9–11 To our knowledge, this study is the first in the medical field and from a developing country to use a cross-sectional study design in a homogeneous population for the assessment of prevalence and uptake of such courses among undergraduate medical students.

Knowledge and enrolment

Our results demonstrate a funnel-shaped participation pattern, with 21.7% of the respondents knowing about MOOCs and 6.5% actually enrolled. Moreover, only 5.4% watched the offered video lectures and 1.2% obtained certificates of completion. Although there are no similar cross-sectional studies with which our results can be compared, the knowledge that approximately one-fifth of Egyptian medical students are familiar with MOOCs is considered promising in a developing country that depends mainly on traditional education. Additionally, these courses are still new, and MOOC providers’ advertisements had little effect in reaching students. Also, there was no medical MOOC offered by an Egyptian institution to date. Social media and the sharing of personal experiences among friends played a vital role in the spread of the MOOCs, raising students’ awareness to its current level. This is in line with the increasing role of social media websites in medical students’ lives, with more than 90% of medical students in the USA using social media.12

Notably, it was obvious that there was a gap between knowledge of MOOCs and enrolment in them, with only one-third of students who knew about MOOCs actually registering in courses. Students reported a lack of time and low Internet speed as the main limitations for MOOC use. Out of these students, 18.4% (23.3% when looking at those enrolled in a medical course) completed the courses and earned certificates. These completion rates are higher than the reported average completion rates in the course demographics. In 2013, The Chronicle of Higher Education suggested an average of 7.5% completion rate,13 while a recent study in 2014 reported a rate of about 6.5%.14 This may be explained by the importance reported by students that obtaining certificates has in terms of adding to their résumés in the hope of improving future employment opportunities. It is interesting to note that about half of them paid to verify their certificates, although there is no academic credit for undergraduates for any MOOCs from any medical school in the USA15 or Egypt at this time.

Although there was no association between gender and students’ knowledge or enrolment, class year had a significant association. Clinical year students were found to have higher knowledge and enrolment rates. This may be due to the high level of stress and pressures experienced by early-year medical students adapting to new academic systems with little time available for extracurricular activities.16 In contrast, students in their final years were reported to have less stress,16–18 with more concern about their career plans and searching for new learning channels to increase their competitiveness.

MOOCs and medicine

Of the enrolled students, 75.7% participated in at least one medical course with a 23.3% completion rate. They strongly agreed that these courses helped them to develop theoretical backgrounds on the topics discussed, with less agreement on their role in developing their clinical skills. This raises questions about the effectiveness of MOOCs with the current lecture-based teaching style in covering the different aspects of medical education, including its clinical part, which requires student–patient interaction. However, in the new and evolving era of online learning, the question of whether or not to waste precious class time on a lecture arises. Students can watch the instructor's lecture remotely in their homes and use class time for learning clinical skills.19 Most current opinions anticipate a complementary role for MOOCs in undergraduate education, with an increasing role in educating those students after their graduation in continuing medical education.15

MOOC limitations in Egypt

Lack of time and slow Internet speed were the two main limitations reported for causing low MOOC enrolment and course completion rates. MOOCs, being a self-learning educational system, requires a considerable amount of time to choose courses, watch videos, take exams and interact through discussions. This imposes a significant time burden on students, leading to the need for an increased commitment beyond their busy regular medical education. Time management, either in the design of courses or from participants, is critical to the enhancement of their performance and increased completion rates.

Low Internet speed is a commonly reported problem facing online education in developing countries.20 This problem prolongs the time needed to watch high-quality videos or to download course content, rendering students less adherent and more susceptible to dropout. The main solution to this problem is enhancing Internet infrastructure in Egypt. Liyanagunawardena et al8 suggested allowing lower resolution versions of the videos as an alternative solution to help engaging students with limited bandwidth. Interestingly, we did not find computer literacy, language or culture as barriers, although it was expected that they would represent problems in Egypt, being a developing country.

MOOC experience satisfaction

Encouragingly, most of the participants who completed MOOCs (n=25) were satisfied with the overall experience. However, there was obvious dissatisfaction regarding student–student and student–instructor interactions. This problem is common in online education in general, with a lack of face-to-face interaction leading to some feelings of isolation and disconnectedness, which are thought to be two main factors affecting dropout rates.21 Some MOOC providers, such as Coursera, support efforts beyond the usual discussion forums to help overcome this issue. These efforts include more peer assessments, social media involvment, Google+ hangouts and real in-person meet-ups. Despite that, more involvement of participants is needed to ensure the full psychological presence.

Study strengths and limitations

The strength of our study is that it included participants from all study years in 10 institutions, covering nearly the entire geographic area of Egypt with a high CI (99%) and high response rate (83.3%). However, our main limitation was the relatively low returned number of participants who enrolled (n=136) and who had certificates (n=25), which makes the analysis of limitations and satisfaction of MOOCs less reliable. However, these results provide an important contribution as a first step in gathering evidence about the prevalence of perception and use of MOOCs in Egypt. In addition, these results will facilitate the ability of future studies to build on our findings and select samples that are representative of students with prior knowledge of MOOCs, leading to a better understanding of their experience.

Conclusions

About one-fifth of undergraduate medical students in Egypt have heard about MOOCs. Students who actively participated showed a positive attitude towards the experience, but better time management skills and faster Internet connection speeds are required. Further studies are needed involving enrolled students in large representative samples, to assess their experiences using MOOCs. In addition, more effort is needed to raise awareness among students of such courses, as most students who had not heard about MOOCs did show interest in participating once they became aware of the courses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Hadeer Alsayed, Islam Shedeed (Menoufia University), Zyad Abdelaziz, Dina Maklad, Ahmed Gebreil, Mahmoud Medhat (Alexandria University), Mohammed Alhendy, Aya Sobhy, Omar Azzam (Al-Azhar University in Cairo), Hassan AboulNour, Sara Elganzory (Tanta University), Mohamed Eid, Aya Talaat, Mohamed Emad (Beni Suef University), Mohamed Abdelzaheer, Ahmed Abdelhamed, Ahmed Saleh (Suez Canal University), Ahmed Zain, Khaled Ghaleb, Yossri Mohamed (Benha University), Ahmed Alaa, Mohamed Gamal (Assuit University), Marina Nashed, Ibrahim Abdelmone’m (Ain Shams University), and Bassant Abdelazeim and Ramadan Zaky (Cairo University) for their highly-valued assistance in data collection. In addition, we acknowledge Bishoy Gouda (Canada), Susannah L Bodman (USA), Melanie Haines, Marion Mapham (Australia), Mohamed Aleskandarany (UK) and Mohamed Alaa (Egypt) for their much-appreciated help in the English revision of our paper. None of them received compensation for their assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: OAA, AER and AH were responsible for the conception and design of the study. OAA and AER coordinated the study and managed the data collection. OAA, AER, ARE, AA, AAA, SYD, HAH, RS, ONK, AMA, AMN and DSS collected the data. Hassouna carried out the analyses; OAA, AER, AH, ARE, ONK and AAA contributed to interpretation of the findings. OAA, ARE and AA wrote the first draft of the manuscript while AER, AH, AAA, ONK, HAH, RS, SYD, DSS, AMA and AMN made a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: All funding required was provided by Aboshady and Radwan at their own expense.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board at Menoufia University, Faculty of Medicine, Egypt.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gooding I, Klaas B, Yager JD et al. Massive open online courses in public health. Front Public Health 2013;1 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy MB. MOOCs 101: an introduction to massive open online courses. Med Ref Serv Q 2014;33:85–91. 10.1080/02763869.2014.866490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappano L. The year of the MOOC. The New York Times 2013.

- 4.A Triple Milestone: 107 Partners, 532 Courses, 5.2 Million Students and Counting!Coursera Blog: Coursera 2013.

- 5.Liyanagunawardena TR, Williams SA. Massive open online courses on health and medicine: review. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e191 10.2196/jmir.3439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB et al. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med 2013;88:1418–23. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36a07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooke M, Irby DM, ÒBrien BC. Educating physicians: a call for reform of medical school and residency. John Wiley & Sons, 2010;25:193–5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liyanagunawardena T, Williams S, Adams A. The impact and reach of MOOCs:a developing countries’ perspective. eLearning Papers 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emanuel EJ. Online education: MOOCs taken by educated few. Nature 2013;503:342–2. 10.1038/503342a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Group ME. MOOCs @ Edinburgh 2013: Report #1. The University of Edinburgh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huhn C. UW-Madison massive open online courses (MOOCs): preliminary participant demographics: Academic Planning and Institutional Research, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosslet GT, Torke AM, Hickman SE et al. The patient-doctor relationship and online social networks: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1168–74. 10.1007/s11606-011-1761-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolowich S. The professors who make the MOOCs. The Chronicle of Higher Education 2013. http://chronicle.com/article/The-Professors-Behind-the-MOOC/137905/#id=overview [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jordan K. Initial trends in enrolment and completion of massive open online courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 2014;15:133–60. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harder B. Are MOOCs the future of medical education? BMJ 2013;346:f2666 10.1136/bmj.f2666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlin M, Joneborg N, Runeson B. Stress and depression among medical students: a cross-sectional study. Med Educ 2005;39:594–604. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guthrie E, Black D, Bagalkote H et al. Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: a five-year prospective longitudinal study. J R Soc Med 1998;91:237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassols AM, Okabayashi LS, Silva AB et al. First- and last-year medical students: is there a difference in the prevalence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms? Rev Bras Psiquiatr 2014;36:233–40. 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frehywot S, Vovides Y, Talib Z et al. E-learning in medical education in resource constrained low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health 2013;11:4 10.1186/1478-4491-11-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angelino LM, Williams FK, Natvig D. Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. J Educators Online 2007;4:n2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prober CG, Heath C. Lecture halls without lectures-a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1657–9. 10.1056/NEJMp1202451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.