Abstract

Objectives

This paper aimed to systematically evaluate the mental health and well-being outcomes observed in previous community-based obesity prevention interventions in adolescent populations.

Setting

Systematic review of literature from database inception to October 2014. Articles were sourced from CINAHL, Global Health, Health Source: Nursing and Academic Edition, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES and PsycINFO, all of which were accessed through EBSCOhost. The Cochrane Database was also searched to identify all eligible articles. PRISMA guidelines were followed and search terms and search strategy ensured all possible studies were identified for review.

Participants

Intervention studies were eligible for inclusion if they were: focused on overweight or obesity prevention, community-based, targeted adolescents (aged 10–19 years), reported a mental health or well-being measure, and included a comparison or control group. Studies that focused on specific adolescent groups or were treatment interventions were excluded from review. Quality of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcomes were measures of mental health and well-being, including diagnostic and symptomatic measures. Secondary outcomes included adiposity or weight-related measures.

Results

Seven studies met the inclusion criteria; one reported anxiety/depressive outcomes, two reported on self-perception well-being measures such as self-esteem and self-efficacy, and four studies reported outcomes of quality of life. Positive mental health outcomes demonstrated that following obesity prevention, interventions included a decrease in anxiety and improved health-related quality of life. Quality of evidence was graded as very low.

Conclusions

Although positive outcomes for mental health and well-being do exist, controlled evaluations of community-based obesity prevention interventions have not often included mental health measures (n=7). It is recommended that future interventions incorporate mental health and well-being measures to identify any potential mechanisms influencing adolescent weight-related outcomes, and equally to ensure interventions are not causing harm to adolescent mental health.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was the first to systematically review mental health outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions among adolescents.

This study ensured rigorous methodology by following PRISMA guidelines and evaluated quality of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines to allow findings to be interpreted with respect to the quality of studies in which they are found.

A limitation of this review was that a meta-analysis was not possible due to study heterogeneity in differing components of the interventions and different measures of mental health outcomes at follow-up.

Study biases may be present due to interventions having the primary outcome of weight reduction; therefore, mental health measures at outcome may have been under-reported or not reported at all.

Background

Adolescent obesity prevention remains a high priority given negative health consequences of overweight/obesity both during adolescence and later in life. It has been suggested that prevention efforts should be community-based to meet the complex and multidimensional nature of obesity.1 2 Importantly, recent research also suggests that there is a high comorbidity between poor mental health and obesity and this may reflect some shared underlying mechanisms and common potentially modifiable risk factors.3 4 Changes in physical activity and diet patterns have been linked to mental health outcomes and compelling evidence suggests that unhealthy weight-related risk factors are bi-directionally associated with common mental health disorders.5 There is potential then that interventions aiming to promote healthy weight among adolescents may also impact on mental health and well-being outcomes.

Overweight and obesity treatment programmes appear to have positive psychological impacts for children and adolescents; a systematic review examining the impact of weight management programmes on self-esteem found that despite variance in methodology and treatment design, there were overall positive effects for self-esteem following weight treatment programmes in paediatric overweight populations.6 This review highlighted the importance of considering both physical and emotional health outcomes from weight-based treatment for overweight adolescents. A second review examined the psychological outcomes of weight loss following behavioural and diet interventions in overweight/obese populations7 finding that improvements in body image and health-related quality of life were consistently associated with weight loss.

Given weight-related stigma and particular sensitivity to body image concerns during adolescence, it is also important to ensure overweight/obesity focused programmes are not causing psychological harm to participants. O'Dea8 identified the importance of prevention versus treatment for obesity, emphasising that prevention initiatives must encompass all the dimensions of a child's health and that other healthy behaviours should not be forfeited in place overweight and obesity prevention. Care must be taken to avoid further stigmatising overweight and obese young people, and to ensure the health messages delivered in obesity prevention interventions do not damage any other domains of health, such as normal eating behaviours, or self-esteem.

One systematic review9 examined prevention of mental disorders in children, adolescents and adults, with studies included if they included interventions aimed at positively affecting mental health outcomes. Interventions were mostly based on cognitive behavioural therapy/counselling sessions, drug therapy or prosocial behaviour management programmes. This review did not examine obesity prevention interventions. One other review10 examined mental health and wellness in relation to the prevention of childhood obesity in studies from January 2000 to January 2011. This review identified that psychosocial emotional health is one of the most neglected areas of study in childhood overweight/obesity and that many recommendations focus on physical outcomes such as body mass index, ignoring the impact on psychological or social well-being. Three systematic reviews have examined community-based obesity prevention studies in children and adolescents; however, none of these reviews investigated mental health and well-being outcomes either as intentional effects or side effects of the interventions.11–13

Currently, our understanding of mental health outcomes in obesity prevention interventions is limited because existing systematic reviews are limited to specific high-risk groups such as individuals classified as overweight or obese,7 10 individuals undergoing weight management6 or mental health treatment programmes.9 For community-based obesity prevention interventions, previous reviews have focused solely on weight status outcomes, and none have reported mental health and well-being outcomes.11–13 It remains unknown whether positive mental health effects have been achieved following such interventions and whether obesity prevention interventions protect mental health and well-being to ensure no harm has been done.

Despite emerging empirical evidence highlighted above, there is not yet a clear synthesis of the literature relating to the effect of obesity prevention interventions on mental health outcomes. Without this understanding, efforts to target and protect mental health in such interventions are limited. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the mental health outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions among adolescents, and develop a set of recommendations for future interventions. This review is limited to controlled studies.

The specific questions addressed in this review were:

What mental health and well-being outcomes have been examined in community-based obesity prevention interventions for adolescents and what do the findings reveal?

What limitations exist in the research to date and what recommendations can be made for future interventions?

Methods

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The search was designed to identify studies that were community-based obesity prevention interventions, targeting adolescent populations. Community-based interventions were defined as those that target a group of individuals or a geographic community but are not aimed at a single individual. This included cities, schools and community healthcare centres. It did not include clinical settings. Adolescence was defined as the period including and between 10–19 years as defined by the WHO. Studies that were randomised control trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental and natural experiments were eligible for selection. Inclusion criteria were (1) primary research; (2) overweight or obesity prevention interventions; (3) community-based; (4) targeted adolescent population; (5) mental health measure reported at baseline and follow-up; (6) included a comparison or control group and (7) were published through October 2014. Exclusion criteria were (1) obesity treatment/management interventions; (2) targeted children or adult populations and (3) focused on specific high risk (such as overweight/obese adolescents), or that were designed to suit specific demographics such those living in rural areas. Studies were not excluded based on ethnicity. This review was focused on interventions to prevent overweight and obesity, and therefore studies examining eating disorders and underweight management were not eligible for review. Exclusion criteria were set to ensure studies examining adolescents who were representative of the broader population were sourced.

Definitions of outcomes

Mental health and well-being outcomes included any diagnosed psychopathologies, or symptoms of psychopathologies (eg, depression or depressive symptoms). Given that obesity prevention interventions have rarely investigated psychological and cognitive mediators,14 studies that included health-related quality of life, self-efficacy and other psychosocial factors were eligible for inclusion. Owing to outcome measures utilising different measurement tools, there were no principle summary measures set. The overall findings in relation to mental health and well-being were summarised individually and combined.

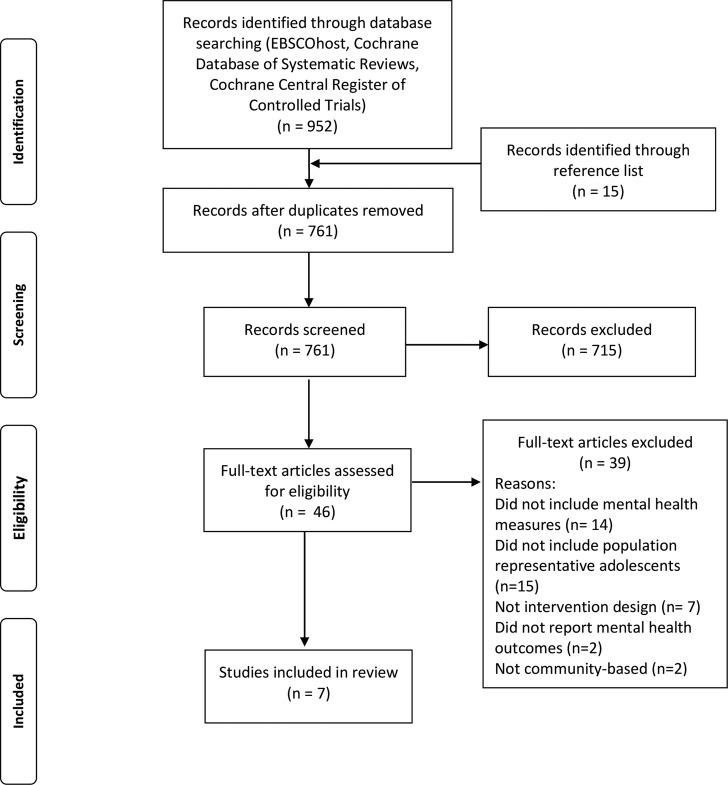

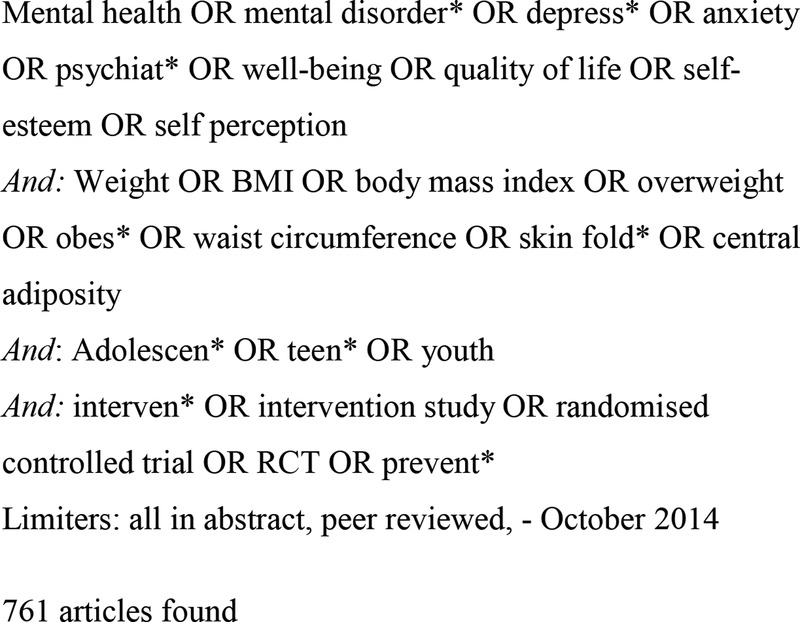

Search strategy

Articles for this review were sourced from CINAHL, Global Health, Health Source: Nursing and Academic Edition, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES and PsycINFO, all of which were accessed through EBSCOhost. In addition, the same search was also performed on the Cochrane Database to ensure all relevant articles were screened for eligibility. The search was limited to peer-reviewed paper published from database inception through October 2014. A range of search terms was used to maximise the yield of the search for studies that conducted a community-based obesity prevention intervention among adolescents and included a mental health or well-being measure. Search terms were selected based on components of obesity prevention interventions, community settings and mental health/well-being outcomes. Mental health and well-being outcomes are described in more detail in the following section. The full search strategy including search terms can be found in figure 1. The reference lists of selected articles and reference lists of other systematic reviews were screened by two independent authors to identify all relevant articles for potential study selection. Disagreements in study selection were resolved by a third reviewer. The studies included in the previously mentioned systematic reviews10–13 examining community-based obesity preventions were scanned to determine whether they included adolescent samples, and if so, the original article was sourced and the full text was assessed for eligibility.

Figure 1.

Search terms and strategy used in CINAHL, Global Health, Health Source: Nursing and Academic Edition, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES and PsycINFO, all of which were accessed through EBSCOhost. In addition, the same search was also performed on the Cochrane Database to ensure all relevant articles were screened for eligibility.

Data extraction and data synthesis

Two authors (EH and LM) screened titles, abstracts and reference lists for potential inclusion in this review. Forty-one articles were selected for full-text review to assess eligibility for inclusion. A standardised form for data extraction was created for study aim, characteristics, participants, intervention type, outcome measures and main findings (table 1). Data were synthesised by categorising the components of the obesity prevention intervention and by the mental health outcome the study examined (table 2). Mental health outcomes at follow-up were extracted and used as the main findings for this review. The quality of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (table 3).15

Table 1.

Interventions designed to prevent overweight/obesity that include mental health outcomes in adolescents

| Study | Sample and setting | Design and intervention | Measures | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fotu et al16 Tonga Aim: to evaluate the outcomes of a 3-year, quasi-experimental study of community-based obesity interventions among Tongan adolescents in three districts. MYP. Study length: 3 years |

Sample: Tongan secondary students, baseline overweight/obesity 46%, Tongan 100% Intervention group: n=815, mean age (baseline) 14.4±2.0 years, male 46% Control group: n=897, mean age (baseline) 15.2±1.8, male=41%. follow-up rate: 75% |

Formed part of the Pacific OPIC study. Quasi-experimental design, longitudinal cohort follow-up, baseline (2006) and follow-up (2008). Intervention group: The intervention group were exposed to social marketing approaches, community capacity building and grass roots activities to promote healthy behaviours Control group: Did not receive the MYP project, but anthropometry measures and QoL were taken at baseline and follow-up |

Mental health: Two instruments measured health-related QoL, AQoL-6D, PedsQoL 4.0 Anthropometry: Objectively measured height and weight. The 2007 WHO Reference standards for age/gender specific body mass index centiles and cut-offs were used to determine weight status |

One of the measures of QoL (PedsQoL) showed a smaller increase in the adolescents from the intervention group, compared with the less urbanised comparison group (p<0.001). Lower levels of weight gain were observed in male adolescents compared with female, indicating the importance that gender plays in values behaviours, and lifestyle |

| Huang et al17 USA Aim: to examine the effect of a 1-year intervention targeting PA, sedentary and diet behaviours among adolescents on self-reported body image and self-esteem. PACE+ intervention Study length: 1 year |

Sample:657 adolescents, age range 11–15 years, baseline 26% overweight/obesity, 53% female Intervention group: female n=175, boys n=166 Control group: female=174, boys n=142 |

RCT, 1 year longitudinal follow-up, data collections occurred at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Intervention group: the PACE+ included a tailored interactive computer program for assessment and goal setting, and counselling in relation to PA and sedentary behaviours. Control group: received computer assessment and counselling in relation to sun protection |

Mental health: Body image was measured via self-report Body Dissatisfaction subscales of the Eating Disorders Inventory Self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Anthropometry: Height and weight were objectively measured. BMI was determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention national norms |

There were no intervention effects on body image or self-esteem for either boys or girls. Self-esteem and body dissatisfaction did not worsen as a result of participating in the intervention.Girls in the intervention group who experienced weight reduction of maintenance at 6 and 12 months reported improvements in body image satisfaction (p=0.02) over time compared with participants who experienced weight gain |

| Kremer et al18 Fiji Aim: to evaluate a community-based obesity intervention (HYHC) in Fijian adolescents, designed to strengthen community capacity to promote healthy eating and regular PA to reduce overweight and obesity in Fijian adolescents. Study length: 2 years |

Sample: Fijian secondary school students aged 13–18 years. Baseline overweight/obesity 21% Intervention group: secondary school students from 7 schools, mean age 15.4±0.9 (baseline), 17.6±0.9 (follow-up); n=879 (follow-up), male=46% Control group: Secondary school students from 11 comparison schools, mean age 15.2±1.1 (baseline), 17.3±0.9 (follow-up); n=2069 (follow-up), male=43% Follow-up rate: 33% for intervention group, 45% for control group |

Formed part of the OPIC study. Quasi-experimental design, with the intervention being applied over three school years (2006–2008). Intervention group: the HYHC intervention was delivered over three school years, via school events, canteen, awareness programmes, healthy lunches, promotion of activities such as walking to school, and training of physical education teachers. Control group: did not receive the HYHC programme, but completed questionnaires and anthropometric measuring at baseline and follow-up |

Mental health: Two instruments measured health-related QoL: AQoL-6D and PedsQoL. Anthropometry: Height, weight and body fat percentage were objectively measured by trained researchers. The 2007 WHO Reference standards for age/gender specific BMI centiles and cut-offs were used |

At follow-up the intervention group had lower percentage body fat (p<0.001) and smaller increase in QoL (PedsQoL: p<0.001, AQoL: p<0.05) than the comparison group (controlled for age, gender and ethnicity) |

| Melnyk et al19 USA Aim: to evaluate the preliminary efficacy of a manualised educational and cognitive behavioural skills-building programme, on Hispanic adolescents’ healthy lifestyle choices as well as mental and physical health outcomes. Study length: 9 weeks |

Sample: 19 Hispanic adolescents enrolled in health classes in a South-western US high school, Mean BMI baseline 27.1 (8.88), Hispanic 100% Intervention group: mean age 15.67±0.65; n=12, male=42% Control group: mean age 15.28±0.53; n=7, male=14% Follow-up rate: 89% |

RCT Intervention group: Received the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN programme; based on educational information on healthy lifestyles, strategies to build self-esteem, stress management, goal setting, communication, nutrition and PA, delivered over 9 weeks. Students wore pedometer everyday over 9-week period. Control: control group received instruction in health topics that were not contained in the intervention group, such as acne, first aid. No PA component, but students did wear pedometers |

Mental health: Beck Youth Inventory. Measures; depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, anger, disruptive behaviour and self-concept. Anthropometric measures: Height and weight measured at baseline and follow-up. BMI reported however criteria for percentile cut-off were not reported |

Adolescents in the intervention group reported a significant decrease in anxiety symptoms (d=−0.56, p<0.05) from baseline to post-intervention follow-up. The was a decrease in depressive symptoms (d=0.27) in overweight adolescents (BMI≥85th percentile) in the intervention group, however this decrease was not significant (p=0.35). No gender differences were reported. |

| Millar et al20 Australia Aim: to evaluate the outcome results of a 3-year obesity prevention intervention (IYM) study implemented in secondary schools in Australia. Study length: 3 years |

Sample: 2054 secondary school students, percentage overweight/obese baseline 29%, ethnicity not reported Intervention group: 5 secondary schools, mean age=14.5±1.40 at baseline, n=1276, male=60% Control group: 7 secondary schools (4 government, 1 catholic, 2 Christian), mean age 14.7±1.45 at baseline, n=778, male=46% Follow-up rate: 69% (intervention), 66% (comparison) |

Formed part of the OPIC study. Quasi-experimental, longitudinal cohort design, baseline measurements were collected from 2005 to 2006 and follow-up in 2008. Intervention group: Received IYM 3-year programme targeting secondary school students aged 12–18 years. Programme focused on building capacity of families, schools and communities to promote healthy eating and PA. Control group: Completed questionnaires at baseline and follow-up but did not receive IYM programme |

Mental health: Two instruments measured health-related QoL: AQoL-6D and PedsQoL. Anthropometric measures: Height and weight objectively measured to determine BMI based on WHO Reference 2007 |

Adolescents in the intervention group had a relative reduction in body weight (p<0.05) compared with the comparison group. No significant difference in QoL was found between comparison group and intervention group. This intervention demonstrated success in reducing unhealthy weight gain in adolescents through a community-based intervention |

| Simon et al21 France Aim: to evaluate the outcomes of the ICAPS, aimed at preventing excessive weight gain and cardiovascular risk in adolescents by promoting PA Study length: 4 years |

Sample: 954 secondary school students from France. Age range 11.7 years±0.6, 24% overweight prevalence at baseline Intervention group: N=255 females (mean age 11.51±0.03) 220 males (mean age 11.58 years±0.04) Control group: N=231 females (mean age 11.68 years±0.04) 248 males (mean age 11.77±0.04) |

RCT Intervention group: received the ICAPS programme, a multilevel programme aimed at modifying the personal, social and environmental determinants of PA. ICAPS included school setting, and numerous partnerships at different levels (teachers, parents, community agencies). Control group: students in control schools follow their usual school curriculum and physical education classes |

Mental health: Stanford Adolescent Heart Health Program assessed self-efficacy, social influence and intention toward PA. Anthropometric measures: Objectively measured height and weight by trained researchers. International Obesity Task Force age-based and sex-based cut-offs. Waist and hip circumference were objectively measured |

No significant intervention effects were found between intervention and control for self-efficacy, intention and social support. Six-month results showed increased PA and decreased sedentary behaviour |

| Utter et al22 New Zealand Aim: to evaluate the effectiveness of the Living 4 Life study, a youth-led, school-based intervention to reduce obesity in New Zealand, by improving nutrition and increasing PA. Study length: 3 years |

Sample: Secondary school students aged 9–13 years at baseline, New Zealand. 1634 students at baseline, 1612 at follow-up. Mean BMI baseline 25.36 Intervention group: 4 schools, mean age not reported, n=953, male=50% (baseline), n=1023, male=43% (follow-up) Control group: Two comparison schools, mean age not reported, n=681, male=46% (baseline), n=589, male=47% (follow-up) Follow-up rate: Cross-sectional comparison, participation rate 66% |

Formed part of the OPIC study. Quasi-experimental, comparisons made by two cross-sectional samples within schools. Baseline data including anthropometry and questionnaires were completed at baseline (2005) and follow-up (2008). Intervention group: The intervention aimed to create opportunities for meaningful participation, quality relationships, and to create opportunities for student training and development. Control group: Did not participate in the Living 4 Life intervention, however did complete questionnaires and anthropometric measurements at baseline and follow-up |

Mental health: Two instruments measured health-related QoL: AQoL-6D and PedsQoL. Anthropometric measures: Height, weight and body fat percentage, were collected by trained researchers. The 2007 WHO Reference standards for age/gender specific body mass index centiles and cut-offs were used. |

There were no significant differences in findings of weight or QoL in intervention or comparison from base line to follow-up. Results adjusted for gender and no gender differences in outcomes were reported. |

AQoL-6D, Assessment of Quality of Life inventory; BMI, body mass index; HYHC, Health Youth Healthy Communities; ICAPS, Intervention Centres on Aolescents’ Physical activity and Sedentary behaviour; IYM, It's Your Move; MYP, Ma'alahi Youth Project; OPIC, Obesity Prevention in Communities; PA, physical activity; PACE, Patient-Centred Assessment and Counseling for Exercise Plus Nutrition Project; PedsQoL, Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 2.

Mental health outcomes (shaded) and community-based obesity prevention components of reviewed studies

| n | Setting | Community capacity building | Increased opportunity for PA or HE | Educational/curriculum component | Environmental component | Counselling/psychology component | MH disorders/symptoms | HRQoL | Self-perception | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fotu et al16 | 1712 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Huang et al17 | 657 | C | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Kremer et al18 | 2948 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Melnyk et al19 | 19 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Millar et al20 | 2054 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Simon et al21 | 954 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Utter et al22 | 1612 | S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

C, community; HE, healthy eating; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MH, mental health; PA, physical activity; S, school.

Table 3.

Assessment of quality of studies based on mental health and well-being outcome using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system

| Outcome Number of studies (number of participants) |

Study limitations | Consistency | Directness | Precision | Publication bias | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health disorder/symptoms 1 (19) | ||||||

| Serious limitations (−1) Quasi-randomised design. Concealment of allocation and blinding not described.19 Loss to follow-up: 11% Did not report intention to treat analysis. Sparse data (<200) |

Important inconsistency (−1) Decrease in depressive symptoms in obese adolescents only19 |

Indirectness (−1) Sample of Hispanic adolescents enrolled in a South-Western US high school |

No important imprecision | Unlikely Study reported both positive and negative results |

Very low | |

| Health-related quality of life 4 (8326) | ||||||

| Serious limitations (−1) Quasi-randomised design. Concealment of allocation and blinding not described. Loss to follow-up: 25–35%,16 20 22 55–67%.18 Did not report intention to treat analysis |

Important inconsistency (−1) Important gender differences in mental health and weight-related measures, although not consistent20 |

Indirectness (−1) Interventions taken place in western/high-income countries |

No important imprecision | Unlikely Studies reported both positive and negative results |

Very low | |

| Self-perception 2 (1611) | ||||||

| Serious limitations (−1) One study was randomised,17 one study was quasi-randomised.21 Concealment of allocation and blinding not described. Loss to follow-up: between 25% and 35%,17 one study did not report loss to follow-up.21 Did not report intention to treat analysis |

Important inconsistency (−1) Mental health changes linked to weight change inconsistently17 |

Indirectness (−1) Interventions taken place in western/high-income countries |

No important imprecision | Unlikely Studies reported both positive and negative results |

Very low | |

Results

Summary of included studies

The search strategy yielded 621 abstracts through EBSCOhost and 140 studies through Cochrane Database which were screened by authors for possible inclusion. After screening, 46 full-text articles were selected and examined in detail to determine eligibility. A further 39 articles were excluded at this stage; 14 studies did not include mental health outcome measures,23–36 14 studies sampled specific adolescent groups such as those at risk or already overweight/obese,37–45 disadvantaged or sedentary adolescents,46 47 or younger or older age groups,48–50 six studies did not include an intervention design with a comparison or control group,51–56 two studies failed to report mental health measures at follow-up,29 57 two studies sampled from specific communities such a rural58 or low-income schools,59 and one study focused on disordered eating behaviours60 leaving seven eligible studies for review. See figure 2 for flow chart process of article inclusion. A list of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion can be found in online supplementary table S1.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of studies that were identified using the search terms and strategy, articles screened for eligibility, included/excluded with reasons, following PRISMA guidelines.

Quality of evidence according to the GRADE rating system is summarised in table 3. Owing to significant limitations in study design, inconsistency, lack of directness and sparse data for outcome of mental health disorders/symptoms the overall quality of evidence was very low. A full description of the GRADE rating system is described in Balshem et al15

Two interventions took place in the USA,17 19 and one each in France,21 Australia,20 Tonga,16 Fiji18 and New Zealand.22 The details pertaining to study aim, intervention, design and outcomes are outlined in table 1. The mental health domains measured in each study are summarised in table 2. Six of the seven reviewed studies had samples consisting of close to half (40–55%) males.16–18 20–22 One study had higher proportions of females at 72%.19

Community-based obesity prevention interventions

Design methodology of the reviewed interventions included RCTs17 19 21 and quasi-experimental studies.16 18 20 22 Four of the reviewed studies had interventions that lasted 2–3 years,16 18 20 22 and the other studies lasted 1 year,17 6 months21 and 9 weeks.19 The interventions took place in schools16 18–22 and in the general community17 and shared similar specific intervention components; increased opportunities for adolescents to engage in physical activities and healthy eating behaviours; included educational sessions in relation to physical activity, nutrition and behaviours promoting healthy weight; targeted environmental aspects such as increased water fountains in school or improved canteen quality, and incorporated counselling or psychology sessions in relation to healthy living (see table 2). Community capacity building for obesity prevention was an explicit component in four of the reviewed studies. Four of the interventions17–20 successfully reduced or prevented unhealthy weight in adolescents based on significant changes in weight from preintervention to postintervention. Two studies resulted in no significant effect in anthropometry postintervention.16 22 One study21 did not report anthropometric outcomes at follow-up.

Each of the seven interventions included a mental health measurement as an outcome, which fell into one or more of the following categories: mental health disorders (including depression and anxiety), health-related quality of life and self-perception referring to one's beliefs about oneself including self-concept, self-worth, self-esteem, body satisfaction and physical self-worth. Findings for each mental health outcome are discussed in detail below. Owing to heterogeneity in population characteristics, intervention components, outcome measures and duration of interventions, it was not possible to complete a meta-analysis.

Mental health outcomes measured in community-based obesity prevention interventions

Mental health disorders/symptoms

Mental health disorders were examined as outcomes in one of the reviewed studies.19 Melnyk et al 19 reported a moderate decrease in anxiety symptoms, as indicated by the Beck Youth Inventory (BYI)61 from preintervention to postintervention (d=−0.56, p<0.05) in adolescents following a 9-week healthy lifestyles programme. The intervention consisted of 15 50 min sessions based on educational information on healthy lifestyles, strategies to build self-esteem, nutrition and physical activity. No significant mean difference was observed for depressive symptoms (Cohen's d=−0.32, p=0.11).

Health-related quality of life

All four of the Pacific Obesity Prevention in Communities (OPIC) studies16 18 20 22 measured health-related quality of life by the Adolescent Quality of Life Inventory (AQoL)62 and Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQoL).63 Fotu et al16 found that health-related quality of life increased in the intervention group at follow-up according to one measure (PedsQoL), however, remained significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the comparison group (p<0.001). Similarly, Kremer et al18 found the intervention group had smaller increase in health-related quality of life compared with the comparison group (p<0.05) following a 3-year comprehensive school-based obesity prevention project. The other two OPIC studies, set in Geelong, Australia,20 and Auckland, New Zealand,22 did not find significant changes in HRQoL from baseline to follow-up in either measure.

Self-perception

Two obesity prevention intervention studies among adolescents have included self-perception as an outcome measure.17 21 Huang et al17 assessed self-esteem using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale64 and found no significant differences between intervention and control groups following a 1-year intervention targeting physical activity, sedentary and diet behaviours. Simon et al21 assessed self-efficacy with self-reported questions scored on a six-point Likert scale, and found no significant differences in self-efficacy between comparison and intervention groups following a 6-month programme aimed at preventing excessive weight gain by promoting physical activity.

Discussion

What mental health and well-being outcomes have been examined in community-based obesity prevention interventions for adolescents and what do findings reveal?

An examination of the literature on obesity prevention interventions targeting adolescents in community settings reveals that the following mental health outcomes have been reported: anxiety and depressive symptoms, health-related quality of life, body image, self-worth and self-esteem. Obesity prevention interventions that have included mental health measures as outcomes have taken place most commonly in school settings (n=7) and have had the primary focus on anthropometry at follow-up. The GRADE quality of evidence assessment revealed very low quality of evidence for mental health disorders or symptoms, and low quality of evidence for health-related quality of life and self-perception.

Findings of mental health outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions were mixed. A significant decrease in anxiety symptoms was found in the intervention group compared with controls following a 9-week healthy lifestyle intervention; however, no significant differences were found in depressive symptoms.19 Of the four studies that examined health-related quality of life, two16 18 found significant increases postintervention; however, these increases were smaller than increases observed in the control groups. The other two studies20 22 that examined health-related quality of life did not find any significant changes in health-related quality of life following 3-year obesity prevention interventions in school settings. Two studies found no significant differences in self-esteem or self-efficacy following a 1-year17 and 6-month21 intervention. Common characteristics across the interventions that demonstrated positive mental health outcomes were: inclusion of a physical exercise component, education components targeting healthy living behaviours (specifically healthy eating and physical activity), group-based sessions aimed at both healthy living and provision of opportunities for adolescents to engage in meaningful activities that promote personal development (such as mastery, friendships, leadership). Mechanisms contributing to significant findings are difficult to identify due to heterogeneity in interventions delivered to adolescents.

Interventions that included a cognitive behavioural component, or that were theoretically based on cognitive behavioural theory,21 65 showed positive findings in promotion of mental health and well-being. Cognitive behavioural approach refers to the thoughts and beliefs in relation to behaviour, and this approach is widely accepted as a beneficial therapy for mental health disorders.66–68 Research suggests that adolescents who have stronger beliefs/confidence about their ability to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviours and perceive them as less difficult to perform are more likely to engage in more healthy choices.19 Similarly, opportunities for adolescents to participate in physical activity or diet-related activities provide mastery experience. Bandura69 outlined mastery experience as key in the theory of self-efficacy as this experience builds beliefs about capabilities to produce behaviours that exercise influence over events that affect their lives. Adolescents with greater perceived self-efficacy may be better equipped to maintain healthy lifestyles and deal with adversity such as mental health problems.

Importantly, there were some findings that suggested that intervention groups experienced poorer mental health following obesity prevention interventions compared with control groups.16 18 Authors in one study acknowledged a potential explanation being that the schools that made up the intervention sample were located in a more urbanised main island in Tonga.16 These students may have been exposed to more pressure in terms of achieving high examination results and obtaining employment or overseas tertiary education, compared with the less-urbanised outer island that made up the comparison sample. This may have been a result of biases in sampling technique, however exposes the need for targeted interventions to suit the specific needs of communities, as previously identified as a priority in obesity prevention.70 Additionally, these findings may reflect negative consequences of the obesity prevention interventions. Potential psychological harm due to obesity interventions has been raised in previous research.8 These results demonstrate the need to assess mental health to ensure no harm is being done to adolescents, and also highlights the importance of incorporating explicit aims to protect mental health of participants involved in such interventions.

What limitations exist in the research to date and what recommendations can be made for future interventions?

As identified in this review, there is evidence for positive mental health outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions; however, the number of interventions incorporating mental health measures is few (n=7). The findings of this systematic review demonstrate the dearth of evidence: there were 14 studies excluded from this review for not including a mental health measure, and two studies that included a measure but failed to report the mental health outcomes at follow-up. Given the comorbidity between overweight/obesity and obesogenic behaviours with mental and emotional health,4 5 71 and the increased vulnerability to both unhealthy weight and mental health problems during adolescence,72 73 future interventions should aim to include mental health measures to assess the impact such interventions are having on participant's mental health and well-being. In addition, the issue of directionality still remains in relation to changes in obesogenic behaviours and mental health, and risk factors that may be common to both conditions. Sample biases exist in the reviewed studies with majority of interventions taking place at school16 18–22 and consequently overlooking those adolescents who do not attend school and may represent a population in need of mental health support. Additionally, two16 22 of the seven reviewed studies did not find significant improvements in weight status postintervention, and therefore were not successful in meeting their primary obesity-related aims. The implications of these null findings are outside the scope of this review, however may limit the extent to which mental health can be evaluated as an outcome of the reviewed interventions, given that the effectiveness of interventions’ obesity prevention was varied.

Finally, the current review categorised mental health outcomes by disorders, health-related quality of life or self-perception. The extent to which results can be compared is limited by use of different mental health instruments. Mental disorders, for example, have been measured by diagnostic tools indicating presence of a disorder and also symptomatic measures that indicate suspected presence of disorder symptoms. Such differences affect findings as outcomes vary greatly depending on mental health measures being used.

This review has some limitations. As discussed in the GRADE quality of evidence assessment, many studies published have included less than optimal study designs and this may have biased the findings presented here. As the primary aim of obesity prevention interventions is to reduce or prevent weight gain, this may have led to mental health outcomes being under-reported or not reported at all. Eligible interventions may therefore have not been included in the analysis because of a lack of published data. A further limitation of this review was that a meta-analysis could not be performed due to heterogeneity in the reviewed studies.

This systematic review was also limited in focusing solely on obesity prevention interventions that were community-based. Studies conducted in clinical settings were excluded from this review and these studies may have provided important insight into the mental health and well-being. Previous research examining mental health in clinical settings have discussed psychosocial issues such as weight stigmatisation, and the negative impact this has on client's emotional health.74 Within clinical settings, there also appears to be psychological benefits such as improved body image and health-related quality of life, however these issues have been under-reported due to being considered secondary to the primary aim of obesity prevention,75 which reflects the findings found in the current review.

Despite limitations this study has a number of strengths. There was a range of obesity prevention interventions included in this review including differences in duration, components and country where the intervention took place. The review process was systematic and all studies included were assessed based on strict eligibility and exclusion criteria and robust review methods were used including the searching of multiple databases to ensure all relevant articles were included in this review. The inclusion of the GRADE quality of evidence assessment ensured that the findings presented here could be considered in relation to the quality of research in which they are found.

Future research needs to build on what is already known about the effect of community-based obesity prevention interventions on mental health outcomes in adolescents, as the mechanisms affecting these outcomes are yet to be clearly defined. Mental health is strongly recommended to become a primary outcome of obesity prevention interventions, as potential benefits do exist, however rarely have mental health measures been evaluated (or reported) in community-based interventions. Additionally, two of the reviewed interventions were not successful in reducing or preventing unhealthy weight gain and future research should evaluate the mental health and well-being of adolescents alongside the efficaciousness of obesity prevention initiatives, to highlight potential shared underlying mechanisms.

Conclusions

Comorbidity between poor mental health and poor physical health is well established76 and evidence for successful community-based obesity prevention strategies among adolescents is growing. A focus now needs to be placed on mental health of adolescents in these interventions. It is recommended that obesity prevention interventions incorporate mental health measures to monitor the mental health and well-being of adolescents. This review supports a shift in thinking around mental health, from a secondary outcome of these interventions to a primary outcome alongside overweight and obesity, to ensure that the mechanisms leading to comorbidity can be identified and outcomes can be improved through these interventions. In addition, including such measures can allow care to be taken to ensure that community-based obesity prevention initiatives do not have adverse effects on adolescents’ mental health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EH contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed the literature search, extracted and analysed data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. MF-T and HS contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysed data, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final draft. LM screened articles for eligibility for review. LM and MN were involved in drafting the manuscript, critically revising the piece and approved the final draft. SA critically revised the manuscript and approved the final draft for publication.

Funding: SA is supported by funding from an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council/Australian National Heart Foundation Career Development Fellowship (APP1045836). SA is a researcher on the US National Institutes of Health grant titled Systems Science to Guide Whole-of-Community Childhood Obesity Interventions (1R01HL115485-01A1). SA is a researcher within a NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Obesity Policy and Food Systems (APP1041020).

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science). Circulation 2008;118:428–64. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeMattia L, Denney SL. Childhood obesity prevention: successful community-based efforts. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 2008;615:83–99. 10.1177/0002716207309940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:220–9. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoare E, Skouteris H, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M et al. Associations between obesogenic risk factors and depression among adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2013;15:40–51. 10.1111/obr.12069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacka FN, Kremer PJ, Leslie ER et al. Associations between diet quality and depressed mood in adolescents: results from the Australian Healthy Neighbourhoods Study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:435–42. 10.3109/00048670903571598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowry KW, Sallinen BJ, Janicke DM. The effects of weight management programs on self-esteem in pediatric overweight populations. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32:1179–95. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasikiewicz N, Myrissa K, Hoyland A et al. Psychological benefits of weight loss following behavioural and/or dietary weight loss interventions. A systematic research review. Appetite 2014;72:123–37. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Dea J. School-based interventions to prevent eating problems: first do no harm. Eat Disord 2000;8:123 10.1080/10640260008251219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carolyn D. The effectiveness of mental health promotion, prevention and early intervention in children, adolescents and adults. NZHTA Report 2005;8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell-Mayhew S, McVey G, Bardick A et al. Mental health, wellness, and childhood overweight/obesity. J Obes 2012;2012:281801 10.1155/2012/281801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaya FT, Flores D, Gbarayor CM et al. School-based obesity interventions: a literature review. J Sch Health 2008;78:189–96. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y et al. Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics 2013;132:e201–10. 10.1542/peds.2013-0886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ickes MJ, Sharma M. A systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention programs. J Obes Weight Loss Ther 2013;3:188. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safron M, Cislak A, Gaspar T et al. Effects of school-based interventions targeting obesity-related behaviors and body weight change: a systematic umbrella review. Behav Med 2011;37:15–25. 10.1080/08964289.2010.543194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fotu KF, Millar L, Mavoa H et al. Outcome results for the Ma'alahi Youth Project, a Tongan community-based obesity prevention programme for adolescents. Obes Rev 2011;12:41–50. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00923.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JS, Norman GJ, Zabinski MF et al. Body image and self-esteem among adolescents undergoing an intervention targeting dietary and physical activity behaviors. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:245–51. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer P, Waqa G, Vanualailai N et al. Reducing unhealthy weight gain in Fijian adolescents: results of the Healthy Youth Healthy Communities study. Obes Rev 2011;12(Suppl 2):29–40. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00912.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly S et al. Improving the mental health, healthy lifestyle choices, and physical health of Hispanic adolescents: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Sch Health 2009;79:575–84. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millar L, Kremer P, de Silva-Sanigorski A et al. Reduction in overweight and obesity from a 3-year community-based intervention in Australia: the ‘It's Your Move!’ project. Obes Rev 2011;12(Suppl 2):20–8. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon C, Wagner A, Platat C et al. ICAPS: a multilevel program to improve physical activity in adolescents. Diabetes Metab 2006;32:41–9. 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70245-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Utter J, Scragg R, Robinson E et al. Evaluation of the Living 4 Life project: a youth-led, school-based obesity prevention study. Obes Rev 2011;12(Suppl 2):51–60. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00905.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Osganian SK et al. Effects of decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption on body weight in adolescents: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Pediatrics 2006;117:673–80. 10.1542/peds.2005-0983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiegel SA, Foulk D. Reducing overweight through a multidisciplinary school-based intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:88–96. 10.1038/oby.2006.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh AS, Paw MJMCA, Brug J et al. Dutch obesity intervention in teenagers: effectiveness of a school-based program on body composition and behavior. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:309–17. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L et al. Evaluation of a 2-year physical activity and healthy eating intervention in middle school children. Health Educ Res 2006;21:911–21. 10.1093/her/cyl115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ et al. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE+ for adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:128–36. 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peralta LR, Jones RA, Okely AD. Promoting healthy lifestyles among adolescent boys: the Fitness Improvement and Lifestyle Awareness Program RCT. Prev Med 2009;48:537–42. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pott W, Albayrak Ö, Hebebrand J et al. Treating childhood obesity: family background variables and the childs success in a weightcontrol intervention. Int J Eat Disord 2009;42:284–9. 10.1002/eat.20655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh AS, Paw MJMCA, Brug J et al. Short-term effects of school-based weight gain prevention among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:565–71. 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webber LS, Catellier DJ, Lytle LA et al. Promoting physical activity in middle school girls: trial of activity for adolescent girls. Am J Prev Med 2008;34:173–84. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gortmaker SL, Cheung LW, Peterson KE et al. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:975–83. 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Killen JD, Telch MJ, Robinson TN et al. Cardiovascular disease risk reduction for tenth graders. A multiple-factor school-based approach. JAMA 1988;260:1728–33. 10.1001/jama.1988.03410120074030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenzie TL, Stone EJ, Feldman HA et al. Effects of the CATCH physical education intervention: teacher type and lesson location. Am J Prev Med 2001;21:101–9. 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00335-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMurray RG, Harrell JS, Bangdiwala SI et al. A school-based intervention can reduce body fat and blood pressure in young adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2002;31:125–32. 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00348-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pate RR, Ward DS, Saunders RP et al. Promotion of physical activity among high-school girls: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1582–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jelalian E, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Mehlenbeck RS et al. Behavioral weight control treatment with supervised exercise or peer-enhanced adventure for overweight adolescents. J Pediatr 2010;157:923–8.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotte EMW, de Groot JF, Winkler AMF et al. Effects of the fitkids exercise therapy program on health-related fitness, walking capacity, and health-related quality of life. Phys Ther 2014;94:1306–18. 10.2522/ptj.20130315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staiano AE, Abraham AA, Calvert SL. Adolescent exergame play for weight loss and psychosocial improvement: a controlled physical activity intervention. Obesity 2013;21:598–601. 10.1002/oby.20282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mellin LM, Slinkard LA, Irwin CE. Adolescent obesity intervention: validation of the SHAPEDOWN program. J Am Diet Assoc 1987;87:333–8. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/769/CN-00046769/frame.html [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster GD, Sundal D, McDermott C et al. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a scalable, community-based treatment of childhood obesity. Pediatrics 2012;130:652–9. 10.1542/peds.2012-0344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ et al. New moves: a school-based obesity prevention program for adolescent girls. Prev Med 2003;37:41–51. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrel AL, Clark RR, Peterson SE et al. Improvement of fitness, body composition, and insulin sensitivity in overweight children in a school-based exercise program: a randomized, controlled study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:963–8. 10.1001/archpedi.159.10.963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen B, Shrewsbury VA, O'Connor J et al. Twelve-month outcomes of the loozit randomized controlled trial: a community-based healthy lifestyle program for overweight and obese adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:170–7. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H et al. Efficacy trial of a selective prevention program targeting both eating disorders and obesity among female college students: 1- and 2-year follow-up effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:183–9. 10.1037/a0031235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan PJ, Saunders KL, Lubans DR. Improving physical self-perception in adolescent boys from disadvantaged schools: psychological outcomes from the Physical Activity Leaders randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Obes 2012;7:e27–32. 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00050.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jamner MS, Spruijt-Metz D, Bassin S et al. A controlled evaluation of a school-based intervention to promote physical activity among sedentary adolescent females: project FAB. J Adolesc Health 2004;34:279–89. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blissmer B, Riebe D, Dye G et al. Health-related quality of life following a clinical weight loss intervention among overweight and obese adults: intervention and 24month follow-up effects. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:43 10.1186/1477-7525-4-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robertson W, Thorogood M, Inglis N et al. Two-year follow-up of the ‘Families for Health’ programme for the treatment of childhood obesity. Child Care Health Dev 2012;38:229–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Verhaeghe N, De Maeseneer J, Maes L et al. Health promotion intervention in mental health care: design and baseline findings of a cluster preference randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2012;12:431 10.1186/1471-2458-12-431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loth KA, Mond J, Wall M et al. Weight status and emotional well-being: longitudinal findings from project EAT. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:216–25. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toumbourou JW, Olsson CA, Rowland B et al. Health psychology intervention in key social environments to promote adolescent health. Aust Psychol 2014;49:66–74. 10.1111/ap.12043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Olds T et al. BMI, health behaviors, and quality of life in children and adolescents: a school-based study. Pediatrics 2014;133:e868–74. 10.1542/peds.2013-0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berkey CS, Rockett HRH, Gillman MW et al. One-year changes in activity and in inactivity among 10- to 15-year-old boys and girls: relationship to change in body mass index. Pediatrics 2003;111(4 Pt 1):836–43. 10.1542/peds.111.4.836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kimm SYS, Glynn NW, Obarzanek E et al. Relation between the changes in physical activity and body-mass index during adolescence: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet 2005;366:301–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66837-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prosper MH, Moczulski VL, Qureshi A et al. Healthy for life/PE4ME: assessing an intervention targeting childhood obesity. Californian J Health Promot 2009;7(Special Issue):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonsergent E, Agrinier N, Thilly N et al. Overweight and obesity prevention for adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial in a school setting. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:30–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hawley SR, Beckman H, Bishop T. Development of an obesity prevention and management program for children and adolescents in a rural setting. J Community Health Nurs 2006;23:69–80. 10.1207/s15327655jchn2302_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coleman KJ, Tiller CL, Sanchez J et al. Prevention of the epidemic increase in child risk of overweight in low-income schools: the El Paso coordinated approach to child health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:217–24. 10.1001/archpedi.159.3.217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heinicke BE, Paxton SJ, McLean SA et al. Internet-delivered targeted group intervention for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2007;35:379–91. 10.1007/s10802-006-9097-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1999;8:209–24. 10.1023/A:1008815005736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care 1999;37:126–39. 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melnyk BM, Kelly S, Jacobson D et al. The COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN randomized controlled trial with culturally diverse high school adolescents: baseline characteristics and methods. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;36:41–53. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clcentral/articles/758/CN-00904758/frame 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alavi A, Sharifi B, Ghanizadeh A et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in decreasing suicidal ideation and hopelessness of the adolescents with previous suicidal attempts. Iran J Pediatr 2013;23:467–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnan P, Yeo LS, Cheng Y. School-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for academically underachieving Singaporean adolescents with aggressive and rule-breaking behaviour. Asia Pac J Couns Psychother 2013;4:3–17. 10.1080/21507686.2012.722553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Compton SN, March JS, Brent D et al. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;43:930–59. 10.1097/01.chi.0000127589.57468.bf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bandura A. Self efficacy toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 1977;84:191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allender S, Nichols M, Foulkes C et al. The development of a network for community-based obesity prevention: the CO-OPS Collaboration. BMC Public Health 2011;11:132 10.1186/1471-2458-11-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cornette R. The emotional impact of obesity on children. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2008;5:136–41. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00127.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Merikangas KR, He J-P, Burstein M et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:980–9. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A et al. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care 2008;31:2211–21. 10.2337/dc08-9024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1019–28. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc 2007;107:1755–67. 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanna L, Stuart AL, Pasco JA et al. Physical comorbidities in men with mood and anxiety disorders: a population-based study. BMC Med 2013;11:1–9. 10.1186/1741-7015-11-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.