Abstract

Introduction

The treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) involves different care providers across care sites. This fragmentation of care increases the morbidity and mortality burden, as well as acute health services use. The COPD-Integrated Care Pathway (ICP) was designed and implemented to integrate the care across different sites from primary care to acute hospital and home. It aims to reduce the prevalence of COPD among the population in the catchment, reduce risk of hospital admissions, delay or prevent the progression of the disease and reduce mortality rate by adopting a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach to the management of the patients’ medical conditions. This study on the COPD-ICP programme is undertaken to determine the impact on processes of care, clinical outcomes and acute care utilisation.

Methods and analysis

This will be a retrospective, pre-post, matched-groups study to evaluate the effectiveness of the COPD-ICP programme in improving clinical outcomes and reducing healthcare costs. Programme enrolees (intervention group) and non-enrolees (comparator group) will be matched using propensity scores. Administratively, we set 30% as our target for proportion admission difference between programme and non-programme patients. A sample size of 62 patients in each group will be needed for statistical comparisons to be made at 90% power. Adherence with recommended care elements will be measured at baseline and quarterly during 1-year follow-up. Risk of COPD-related hospitalisations as primary outcome, healthcare costs, disease progression and 1-year mortality during 1-year follow-up will be compared between the groups using generalised linear regression models.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol describes the implementation and proposed evaluation of the COPD-ICP programme. The described study has received ethical approval from the NHG Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB Ref: 2013/01200). Results of the study will be reported through peer-review publications and presentations at healthcare conferences.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, RESPIRATORY MEDICINE (see Thoracic Medicine)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will use a retrospective pre-post matched-groups design to evaluate the effectiveness of the programme in terms of adherence with processes of care, clinical outcomes, healthcare costs and quality of life.

This study will use propensity score matching to reduce selection bias due to the lack of randomisation.

It is envisioned that through this study, the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-Integrated Care Pathway team will be able to identify potential gaps in the programme implementation and design, and implement necessary changes to improve care. This is in line with the organisation's aim to deliver patient-centred care.

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of chronic disease morbidity and mortality worldwide. The disease is a global health problem with a worldwide prevalence of 10.1%.1 In Singapore, COPD is the seventh principal cause of death and the seventh most common condition for hospitalisation.2 COPD patients with complications spent 7.7 days or 79% longer in hospital than patients with COPD without complications.3 The COPD 30-day readmission in JurongHealth is around 30%, which is higher than the all-cause national 30-day readmission rate of 11.6% and other condition-specific readmission rates.4

The GOLD international standards for COPD advise spirometry for the gold standard for accurate and repeatable measurement of lung function.5 However, in Singapore, most solo general practice clinics do not offer the spirometer services necessary for early diagnosis of COPD and for the staging of COPD severity to enable appropriate disease management. Patients with COPD in the community experience poor quality of life due to lack of convenient access to pulmonary rehabilitation.6 Therefore, most patients are diagnosed in the acute care setting and those who experienced repeated exacerbations also obtain care in the specialist outpatient settings.

In response to the need for a cost-effective care model, JurongHealth launched a COPD-Integrated Care Pathway (COPD-ICP) programme in April 2012. This was funded by the Singapore Ministry of Health (MOH). The programme seeks to coordinate care across different healthcare settings. It aims to provide comprehensive care for patients with COPD at different stages of the disease, involving primary, hospital-based, community-based and palliative care.

Similar to other COPD integrated care programmes,7 the programme envisages coordination of care across different sites from primary to home and hospital care. The objectives of the programme are to:

Reduce the prevalence of COPD among the population residing in the Western part of Singapore (catchment area of JurongHealth).

Reduce risk of hospital admissions and healthcare costs.

Delay or prevent the deterioration of disease condition of patients with COPD.

Reduce mortality of patients with COPD.

The programme adopts a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach to the management of patients’ medical conditions. Case managers work with JurongHealth's multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, respiratory technologists, pharmacists, physiotherapists and medical social workers to develop a customised care plan for each patient, empower patients towards self-management through education and help coordinate referrals and patients’ appointments across care sites.

The current scope of our study will focus on the evaluation of the hospital-based segment of the ICP programme. We will use a propensity-score matching method to select a suitable comparator group. Specifically, the aim of our study will be to assess whether the intervention group compared with comparator group has (1) primary outcome: lower risk of COPD-related hospitalisation and (2) secondary outcomes: better adherence to the recommended processes of care, lower overall healthcare and COPD-related inpatient costs, slower disease progression and lower 1-year mortality rate. We will use the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) score to measure patients’ experience of chronic care delivery in congruence with the Chronic Care Model (CCM).8 In addition, we will also use the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score to measure COPD control and hence the quality of life of patients with COPD.

Methods/design

The regional healthcare system

In Singapore, public healthcare is provided by six regional healthcare systems (RHSs): Alexandra Health, Eastern Health Alliance, National Healthcare Group (NHG), National University Health System (NUHS), JurongHealth and Singapore Health Services (SHS). Together, these RHSs provide 80% of all acute care service. The government primary care clinics under NHG and SHS provide approximately 20% of primary care services consumed.

Target patients

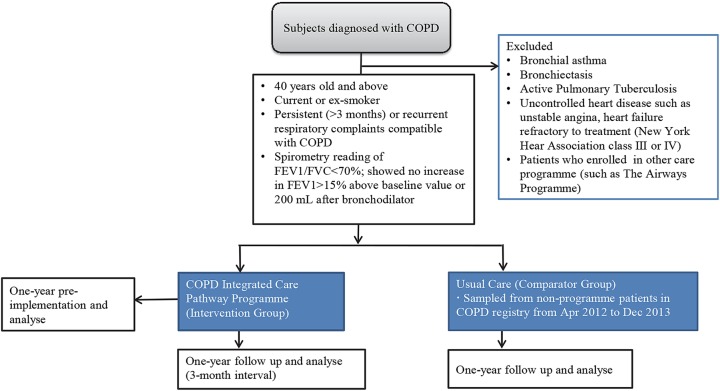

Figure 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients’ enrolment into the COPD-ICP programme. We will exclude patients who have medical conditions other than COPD that are likely to result in death within the next 2 years.

Figure 1.

Identification of the study cohort. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

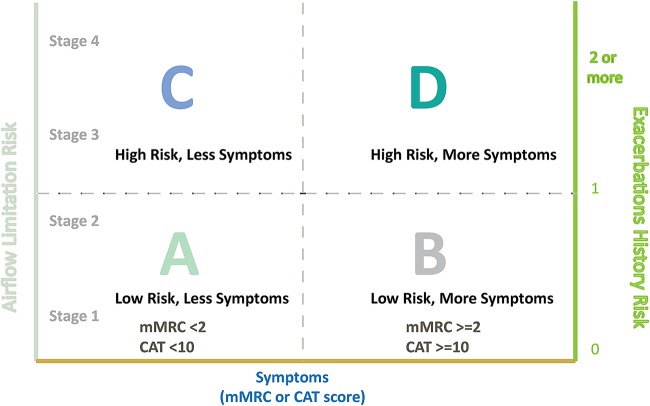

We classify each patient enrolled into the programme based on the Patient Group Classification from updated GOLD guidelines (figure 2).9 10

Figure 2.

Patient classification based on symptoms and risk of exacerbations from GOLD guidelines.9 10 Symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are assessed using mMRC or COPD Assessment Tool (CAT) score. Patient's risk of exacerbations is assessed based on the patient's stage of airflow limitation and/or number of exacerbations that the patient has had over previous 12 months.

Intervention

Table 1 shows the recommended key care elements for each group of patients. Various healthcare team members are responsible for administering the respective key care elements (table 2).

Table 1.

Key care elements for group A, B, C and D patients

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key care elements | At risk | Low risk, less symptoms | Low risk, more symptoms | High risk, less symptoms | High risk, more symptoms | In exacerbation |

| 1. Smoking prevention | ✓ | |||||

| 2. Smoking cessation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 3. Differential diagnosis | ✓ | |||||

| 4. Spirometric diagnosis | ✓ | 18–24 monthly or when clinician suspects patient grouping has changed | ||||

| 5. Patient education | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 6. Drug optimisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| 7. Influenza vaccination (yearly) | Only for elderly (≥65 years old) and those who have concomitant | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 8. BMI assessment (yearly) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| 9. CAT | 6–12 monthly | 6–12 monthly | 6–12 monthly | 3–4 monthly | ||

| 10. Acute ventilation (Invasive/Non-invasive) | ✓ | |||||

| 11. Supported restructured hospital/emergency department discharge | ✓ | |||||

| 12. Home oxygen | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 13. Advance care planning | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

BMI, body mass index; CAT, COPD assessment Tool; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 2.

Care elements administered by the various healthcare team members

| Key care elements | Doctor | Case manager | ICP coordinator | Spirometry technologist | Pharmacist | Physiotherapist | Medical social worker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Smoking prevention | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2. Smoking cessation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 3. Differential diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 4. Spirometric diagnosis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 5. Patient education | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 6. Drug optimisation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 7. Influenza vaccination | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 8. BMI assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 9. CAT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 10. Acute non-invasive ventilation | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 11. Supported RH/ED discharge | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 12. Home oxygen | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 13. Advance care planning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

BMI, body mass index; CAT, COPD assessment tool; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; RH, restructured hospital.

With the implementation of the programme, care plans are designed to cater to each patient's disease severity. Patients are followed up by case managers regularly to ensure that the care elements as aforementioned are strictly adhered to. Case managers will also call the patient 48 h post discharge to reinforce patient education and drugs optimisation, where they play a pivotal role in linking patients to community resources. Hence, with the coordination by case managers, the programme will make care delivery a more seamless and integrated process as compared to when such an initiative is absent.

Evaluation design

A retrospective pre-post, matched-groups design will be implemented for this study. Such a design will be utilised instead of the randomised controlled trial design, as the COPD-ICP programme has been implemented in JurongHealth for almost 2 years. Care resources may also be unnecessarily stretched if two care programmes (usual care and COPD-ICP) are run concurrently.

The study cohort will include individuals diagnosed with COPD who had at least one specialist outpatient visit record in the COPD Registry from April 2012 to December 2013. For our study, we will use the same inclusion and exclusion selection criteria as those for the COPD-ICP programme enrolment (figure 1). Patients with COPD will be identified based on the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10-AM) diagnostic codes (J40.xx and J47.xx).

Patients in the intervention group will be sampled from programme patients in the COPD Registry who received care from JurongHealth from April 2012 to December 2013. A comparator group will be formed from non-enrolees using the matching method described in later sections. Patients for the comparator group will be sampled from non-programme patients in the COPD Registry who received care from non-JurongHealth institutions from April 2012 to December 2013. All data will be collected over 1-year pre-enrolment and 1-year follow-up postenrolment (3-month interval) for enrolees, and over a 1-year period for non-enrolees. The outcomes will be compared between enrolees and non-enrolees (figure 1).

Sample size

Administratively, we set 30% as our target for proportion admission difference between programme and non-programme patients. Thus, a sample size of 56 patients in each group will be needed for statistical comparisons to be made at 90% power. Hence, 62 enrolees (to account for 10% missing data) will be sampled from among those who were enrolled into the programme during the study period and their matching group will be drawn from the comparator group COPD management registry.

Data sources and data

The three main sources of data are (1) COPD Registry: patient demographics; clinical information and outcome variables for enrolees as well as non-enrolees; (2) Patient Case Management (PCM) system database: case managers capture entered data on all recommended key care elements (table 1) common among the four patient groups; and (3) Health System administrative databases: healthcare utilisation cost. Data for 1-year mortality rate will be captured from National Registry of Diseases Office (NDRO).

Covariates include patient demographics and socioeconomic indicators (age, race, gender, nationality, Medisave/Medifund and Medical social worker referral); programme enrolment date; smoking history; medication; comorbidities; severity of COPD (GOLD classification) and CAT score.

The parameters and outcomes of interest for which data shall be collected have been summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Overall of assessments used in COPD-ICP implementation study

| Domain | Type of assessment/outcomes | Pre-ICP implementation | Post-ICP implementation | Concurrent comparator group in COPD disease management registry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | Age, race, gender, nationality, postal code | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Disease | Disease type, disease duration | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Social-economics | Medisave, Medifund, Medical social worker referral | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Programme management | Programme enrolment date | ✓(baseline) | x | x |

| Quality of life | CAT score | ✓(baseline) | ✓ | x |

| Smoking history | Smoking status, number of years of smoking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Key care elements | Refer to table 1 | ✓(baseline) | ✓ | ✓ |

| Disease severity (based on medication use) | Refer to the 2011 GOLD guidelines summary9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Comorbidities and complication | Asthma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Depression | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Congestive heart failure | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Diabetes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hypertension | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CKD stage 3–5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Stroke | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dyslipidaemia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Obesity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Others | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| COPD-related health service utilisation | Hospitalisation, average length of stay | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Number of encounters | Emergency department attendance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Specialist outpatient visit | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Primary care visit | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| COPD-related cost (DRG) | Direct cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Indirect cost | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Mortality | Rate of mortality | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Qualitative measures | Patient assessment of chronic illness care | ✓ | ✓ | x |

CAT, COPD assessment test; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD-ICP, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-integrated care pathway; DRG, diagnosis-related group.

Study outcomes

Hospital admissions and healthcare costs

The primary outcome of this study is hospital admission. Hospital admission refers to inpatient episodes at acute care hospitals managed by three regional health clusters (JurongHealth, NHG and NUHS). Total annual healthcare costs refer to the cost of resources utilised at the primary care clinics, emergency departments, specialist outpatient clinics and inpatient wards of these regional health clusters. To define specific COPD-related hospitalisations and inpatient costs, we have adopted the COPD-related hospitalisation ICD-10-codes used in Jiang et al.11

Disease progression and 1-year mortality rate

Different medications are used during different disease progression stages.9 Owing to the absence of GOLD guidelines in measuring disease progression, we will utilise medication usage to determine the disease progression of patients with COPD. This will be compared between the intervention group and the comparator group. One-year mortality rate is defined as the proportion of patients who died (all causes) during 1-year follow-up for intervention and comparator groups.

Adherence with recommended processes of care and PACIC score

We will use an all-or-none care bundle to monitor adherence with the recommended key care elements for group A, B, C and D patients (table 1) at baseline and 3-month interval. All-or-none care bundle is a process indicator which measures the percentage of patients who adhere with all of the recommended key care elements according to each patient group.12 In addition, we will use the PACIC score to measure patients’ experience of chronic care delivery. The PACIC score is a 20-question survey used to measure patients’ perception on the congruency of the service with the CCM.8 CCM is a guideline that recognises six aspects as key to improving quality of chronic disease management.8 13 The score obtained from the PACIC assessment tool will allow us to assess if the COPD-ICP programme is aligned with CCM.

Quality of life

As there is no locally validated tool to measure quality of life in patients with COPD and the COPD-specific version of St George's Respiratory Questionnaire is too long to administer, we will use the CAT score, which is an eight-question health survey, to measure COPD control in individuals.14 Scores range from 0 to 40 and lower scores indicate better control. Owing to its strong correlation with the COPD-specific version of the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire, it has been used as an alternative tool for assessing quality of life of patients with COPD.14 15–18 Enrolees’ CAT score will be measured at baseline and during their follow-up visits within the first year of enrolment. A CAT score difference of 2 or more (or ≥10%) suggests clinically significant changes in the quality of life.19 The CAT score difference is taken as the difference between the baseline and the best reading within 1 year. This outcome is only available for programme enrolees as CAT score is not routinely collected for non-enrolees.

Statistical analysis

Key recommended processes of care (table 1) will be monitored quarterly to track the adherence and progress of the COPD-ICP programme. Patient baseline characteristics from enrolees and non-enrolees will be described with mean and SD for continuous variables and number and percentage for categorical variables. Differences between COPD-ICP enrolees and non-enrolees will be compared using χ2 statistics for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables.

Since patients are enrolled into the programme based on the institution that they were seen in, there is likely to be imbalance in baseline characteristics between enrolees and non-enrolees. Hence, we will use propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics across enrolees and non-enrolees.20 We will start off by estimating the propensity score, which is the conditional probability of each patient enrolling into the programme given their baseline characteristics, by using multivariate logistic regression.20 Covariates to be included in the regression are: age, gender, race, hospital, subsidy term, the number of hospitalisation or emergency attendances in the past year, number and severity of comorbid conditions, and COPD severity based on medication use. We will then form pairs of enrolee and non-enrolee by using the caliper matching method, within a range of 0.2 of the SD of propensity score.21

Hospital admissions, healthcare costs and mortality

We will compare healthcare costs using a generalised linear model with log link function and γ distribution. For odds of hospital admission and 1-year mortality, we will compare using logistic regression.22

CAT score comparison

To evaluate the quality of life improvement of the patients with COPD using the CAT score as the outcome, the change in CAT score over the 1-year post enrolment time frame will be examined. A paired-sample t test will be used to compare baseline CAT score and the best achieved CAT score over the 1-year time frame.

PACIC score

To evaluate patients’ perception on the programme's congruency with CCM, the average PACIC score for programme enrolees will be computed and benchmarked with PACIC results of other integrated care programmes in the present literature that have showed substantial congruency to the CCM. At present, recommended cut-offs for CCM concordance is set at ≥3.5 in a study with veterans and at ≥4 in another study with older adults at risk of high healthcare costs.23 24

Software

All analyses will be conducted using Stata V.12.

Discussion

In designing the COPD-ICP programme, three key principles have been adopted: right-siting, integration and patient-centredness. It also involves the five standards of care: COPD prevention, early diagnosis, management of stable patients with COPD, treatment and support during acute exacerbations, and care and support at end of life. The model of care concept plan is drafted with reference to various evidence-based guidelines such as the GOLD standard, American College of Physicians guideline on diagnosis and management of stable chronic COPD, and MOH COPD Clinical Practice Guidelines (2006).25 26

This programme serves to close current service gaps to provide comprehensive integrated care along the care continuum in the following ways. Training for primary care physicians in the management of COPD has the potential to enhance care standards at their care setting. A multidisciplinary care team comprising of the clinician, case manager, coordinator and other relevant allied health members has been shown to improve clinical outcomes and life expectancy of patients with COPD.27 Patients admitted for exacerbations are contacted within 48 h from discharge to reinforce patient education and to increase their confidence in self-managing their own condition. Lastly, the case manager plays the role of the liaison between step-down care partners, primary care physicians and patients. This may lower the risk of readmission and reduce the frequency of exacerbation. From an international perspective, similar integrated care models around the world have also shown similar positive results.28 29 These evidences further support JurongHealth in launching and maintaining the COPD-ICP programme.

The rationale behind this programme evaluation stems from the motivation to bolster support for the programme and to identify care gaps for improvement. As such, adherence with processes of care and outcomes such as risk of hospitalisation, CAT score and PACIC score will be used by the team to identify any care gaps, so as to improve the COPD-ICP programme. In addition, healthcare costs, disease progression and 1-year mortality rate will also be used to assess the practicality of sustaining the programme. Furthermore, this study can also potentially add to the mounting evidence in support of integrated care in the healthcare literature.

This study protocol has several strengths. The PACIC survey will be used to assess patients’ experience of the congruency of care to CCM. This is in line with the organisation’s aim to deliver patient-centred care.

The choice of the matched-group patients using propensity scores will replicate the balance in baseline characteristics between compared cohorts achieved through randomisation. This will in turn reduce the effect of selection bias due to the lack of randomisation.21 This step will be vital for making valid conclusions from the economic effectiveness analysis.

This study protocol is limited in several areas. First, even though we will use propensity score matching to reduce the selection bias due to non-randomisation, there might be unmeasured confounders that can affect our results. Second, the data collection process will only account for enrolees and non-enrolees who choose to have their follow-up medical appointments at JurongHealth, NHG or NUHS. Owing to the non-captive nature of the healthcare system in Singapore, patients in Singapore are free to choose healthcare providers outside these clusters on an episodic basis. Hence, such exclusion might lead to underestimation. However, these limitations affect the evaluation of the programme only, but not the quality of care provided at any institution.

In conclusion, the COPD-ICP programme aims to equip primary care partners with the adequate knowledge and skills for managing stable patients with COPD and to right-site patients in order to provide excellent and appropriate care while optimising available healthcare resources. With the support from case managers, the programme does so by discharging patients to primary care doctors so that the clinically stable patients can be managed without the need to see a specialist if not clinically necessary. We believe that this evaluation study can provide an evidence-based assessment of the impact and effectiveness of the COPD-ICP programme. The lessons learnt from this study will be fed back to the COPD-ICP programme team and be useful in informing the design evaluations of other ICP programmes nationally.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol describes the implementation and proposed evaluation of the COPD-ICP programme. The described study has received ethical approval from the NHG Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB Ref: 2013/01200). Results of the study will be reported through peer-review publication and healthcare conference presentations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Ainie Tan (Medical Affairs Department) for her assistance in statistical methods and manuscript review and Mr Kai Pik Tai (Medical Affairs Department) for his suggestions on the statistical analysis portion. The authors would also like to acknowledge Ms Lin Jen Lee and Ms Thaung Yin Min (Information Management, NHG) for their advice and assistance in the study. The authors wish to acknowledge the project team that contributed to the whole implementation of this programme, in particular Nurse Xu Meng and Bariah Rahman (both Case Managers), Ms Rubiah Bte Rahman, Ms Meixian Huang and Ms Siti Mahfuzah Azman (all from Clinical Operations), Dr Muhammad Rahizan, Mr Kian Chong Lim and Ms Ang Hong Koh (all physiotherapists), Mr Timothy Chua and Ms Krutika Menon (both Social Workers), Ms Kimmy Liew (Head, Pharmacy), Mr Chee Chong Ong (Spirometry Technologist) and Dr Thomas Soo (Clinical Director, JMC). They would also like to thank Dr Frederick James Bloom Jr (Geisinger Health Services) for his advice on the implementation strategy of this programme. Special thanks to Dr Chi Hong Hwang and Ms Joanna Chia (Medical Affairs Department) for their support.

Footnotes

Contributors: CXW contributed to study design, data analysis method and writing up of manuscript. WST contributed to study design, statistical analysis and the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. RCKS participated as the project manager of this programme and contributed to the write-up of the manuscript. WY contributed to statistical methods and manuscript review. LSLK participated in the implementation of the model of care and inputs into the manuscript. MPHST contributed to study design and manuscript review. GSWC and TGC are the clinician lead and operational lead of this programme and participated in the design of the COPD model of care. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Ministry of Health (MOH), Singapore Health Services Development Programme (HSDP) grant number MH 36: 18/95.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet 2007;370:741–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Health facts 2011. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teo WS, Tan WS, Chong WF et al. Economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respirology 2012;17:120–6. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lim E, Matthew N, Chong WF, et al. BMC Health Serv Res 2011; 11(Suppl 1):A16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soriano JB, Zielinski J, Price D. Screening for and early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2009;374:721–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61290-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spruit MA. Pulmonary rehabilitation. Eur Respir Rev 2014;23:55–63. 10.1183/09059180.00008013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruis AL, Smidt N, Assendelft WJJ et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;10:CD009437 10.1002/14651858.CD009437.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Improving Chronic Illness Care. The Chronic Care Model. http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Model_Elements&s=18 (accessed 19 Jun 2014).

- 9.Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Proceedings of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; November 2011, Shanghai. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; 2005, Bethesda. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang JH, Andrews R, Stryer D et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in potentially preventable readmissions: the case of diabetes. Am J Public Health 2005;95:1561–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolan T, Berwick DM. All-or-none measurement raises the bar on performance. JAMA 2006;295:1168–70. 10.1001/jama.295.10.1168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002;288:1775–9. 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P et al. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J 2009;34:648–54. 10.1183/09031936.00102509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones PW, Quirk FH, Baveystock CM. The St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire. Resp Med 1991;85:25–31. 10.1016/S0954-6111(06)80166-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherall M, Marsh S, Shirtcliffe P et al. Quality of life measured by the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire and spirometry. Eur Respir J 2009;33:1025–30. 10.1183/09031936.00116808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li X, Zhou Y, Chen S et al. Early intervention with tiotropium in Chinese patients with GOLD stages I–II chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Tie-COPD): study protocol for a multicentre, double-blinded, randomised, controlled trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003991 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weldam SWM, Schuurmans MJ, Liu R et al. Evaluation of quality of life instruments for use in COPD care and research: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:688–7027. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kon SSC, Canavan JL, Jones SE et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:195–203. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert MH, Dalal AA. Clinical and economic outcomes in an observational study of COPD maintenance therapies: multivariable regression versus propensity score matching. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2012;7:221–33. 10.2147/COPD.S27569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cochran WG, Rubin DB. Controlling bias in observational studies: a review. Sankhya Ser A 1973;35:417–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelder J, Wedderburn R. Generalized Linear Models. J R Stat Soc Series B 1972;135:370–84. 10.2307/2344614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jackson GL, Weinberg M, Hamilton NS et al. Racial/ethnic and educational-level differences in diabetes care experiences in primary care. Prim Care Diabetes 2008;2:39–44. 10.1016/j.pcd.2007.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K et al. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:235–42. 10.1007/s11606-009-1192-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health, Singapore. COPD Clinical Practice Guidelines 4/2006. Singapore: Ministry of Health, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a Clinical Practice Guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:179–91. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eeden SF, Burns J. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BCMJ 2008;50:143–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thistlethwaite P. Integrating health and social care in Torbay. Improving care for Mrs Smith. London: The King's Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM et al. Comparison of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:938–45. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-12-200412210-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.