Abstract

Objectives

It has been suggested that statins have an effect on the modulation of the cytokine cascade and on the outcome of patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The aim of this prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was to determine whether statin therapy given to hospitalised patients with CAP improves clinical outcomes and reduces the concentration of inflammatory cytokines.

Setting

A tertiary teaching hospital in Barcelona, Spain.

Participants

Thirty-four patients were randomly assigned and included in an intention-to-treat analysis (19 to the simvastatin group and 15 to the placebo group).

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to receive 20 mg of simvastatin or placebo administered in the first 24 h of hospital admission and once daily thereafter for 4 days.

Outcome

Primary end point was the time from hospital admission to clinical stability. The secondary end points were serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) at 48 h after treatment administration.

Results

The trial was stopped because enrolment was much slower than originally anticipated. The baseline characteristics of the patients and cytokine concentrations at the time of enrolment were similar in the two groups. No significant differences in the time from hospital admission to clinical stability were found between study groups (median 3 days, IQR 2–5 vs 3 days, IQR 2–5; p=0.47). No significant differences in PaO2/FiO2 (p=0.37), C reactive protein (p=0.23), tumour necrosis factor-α (p=0.58), interleukin 6 (IL-6; p=0.64), and IL-10 (p=0.61) levels at 48 h of hospitalisation were found between simvastatin and placebo groups. Similarly, transaminase and total creatine kinase levels were similar between study groups at 48 h of hospitalisation (p=0.19, 0.08 and 0.53, respectively).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the use of simvastatin, 20 mg once daily for 4 days, since hospital admission did not reduce the time to clinical stability and the levels of inflammatory cytokines in hospitalised patients with CAP.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN91327214.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES, IMMUNOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The treatment was assigned on a random basis.

Another unique feature of this trial was that it addressed the question of de novo statin use only in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

The trial did not achieve its recruitment target for determining the effects of statins on time to reach clinical stability.

The exclusion criteria, such as patients receiving certain drugs that are metabolised by the CYP3A4 enzyme system, are limitations to the external validity of the results.

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is one of the most important public health problems worldwide.1 Although mortality in patients with CAP fell dramatically with the introduction of antibiotics in the 1950s, it has changed very little over the past 50 years. Recent studies have found overall mortality rates of 8–15%,2 3 and mortality in patients with CAP requiring intensive care unit (ICU) admission can be as high as 30% despite prompt and appropriate antibiotic therapy.4

The concept of clinical stability is a key component of CAP management. It allows decision-making concerning hospital discharge and treatment length. Physicians are well aware that the evolution of hospitalised patients with CAP within the first days is crucial. In fact, once stability was achieved, clinical deterioration occurred in 1% of cases or fewer.5 6 Studies have shown that excessive inflammatory response is a major cause of treatment failure and mortality in patients with CAP.7 8 Therefore, there is a growing interest in identifying drugs that can modulate the inflammatory response in these patients. Recently, it has been demonstrated that hydroxymethylglutaryl (HMG)-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, commonly known as statins, have immunomodulatory, antioxidative and anticoagulant effects. Experimental studies have shown their effect on the modulation of the cytokine cascade and on the organisation of the immunological response to respiratory infection.9 In addition, most observational studies published to date support the idea that the use of statins may improve the prognosis of CAP.10–12 However, randomised trials are lacking.

In this study, we hypothesised that statin therapy given to hospitalised patients with CAP would reduce the time to clinical stability and the concentration of inflammatory cytokines. The primary end point of this trial was the time from hospital admission to clinical stability, as defined elsewhere.5

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge—IDIBELL, a 700-bed public hospital in Barcelona, Spain, between December 2009 and June 2011. It was registered at International Standard Randomised Control Trial Registry (ISRCTN91327214) before initiation. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reported in agreement with the key methodological items of the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) statement.

Patient eligibility and recruitment process

All patients included in the study were at least 18 years of age, had received a diagnosis of CAP in the emergency department and had required hospital admission according to the following criteria: patients classified in groups I–III of the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI)13 with absolute criteria for hospitalisation (need for oxygen therapy or haemodynamic support, pulmonary cavitation, septic metastasis, lack of response to outpatient antibiotic therapy, uncontrollable vomiting). All patients in groups IV and V of the PSI were also included.

Patients who did not provide prior written consent, who had immunosuppression (HIV/AIDS, solid organ transplant, stem cell transplantation, antineoplastic chemotherapy in the previous 30 days, neutropaenia, prior use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants) and pregnant women were excluded. Similarly, patients receiving statins, antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, azoles, macrolides, niacin, fibric acid and derivatives, protease inhibitors and grapefruit juice were not eligible. Finally, patients who received antibiotic therapy or had been admitted more than 24 h prior to enrolment were also excluded.

Definitions and follow-up

CAP was defined as the presence of an infiltrate on chest radiography plus at least two of the following: fever (temperature ≥38°C) or hypothermia (temperature ≤35°C), new cough with or without sputum production, pleuritic chest pain, dyspnoea, or altered breath sounds on auscultation. The chest radiograph was interpreted by the infectious disease consultant.

Clinical and laboratory data (demographic characteristics, comorbidities, causative organisms, antibiotic susceptibilities, biochemical analysis, empirical antibiotic therapy and outcomes) on all patients were collected using a computer-assisted protocol. Patients were seen daily during their hospital stay by one or more of the investigators. Pathogens in blood, normally sterile fluids, sputum and other samples were investigated using standard microbiological procedures. Urine antigen tests were performed for the detection of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (Binax-Now; Binax, Portland, Maine, USA) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Binax-Now; Binax, Portland, Maine, USA). In addition, real-time PCR was used for the detection of influenza A and B.

Antibiotic therapy was initiated in the emergency department in accordance with hospital guidelines.

Interventions and randomisation

Patients were randomly assigned to receive 20 mg of simvastatin or placebo, which were administered orally in the first 24 h of hospital admission and once daily thereafter for 4 days. A 4-day duration of simvastatin therapy was chosen because of plasma mevalonic acid, the substance being related to pleiotropic effects, drop up to 70% within 1–2 h after the first administration of statins, and because of previous studies having administered immunomodulatory therapies between 3 and 7 days and the median time to clinical stability in our patients is nearly 4 days. Trial packs of identical capsules were prepared by the hospital pharmacy and contained either simvastatin or matched placebo.

Randomisation was performed by using a computer-generated random code with a block size of 10. The random code was held centrally by the clinical epidemiologist and was delivered directly to the pharmacist in charge of the preparation of the masked capsules. All clinical and study personnel, and patients, remained blinded to the study group assignment throughout the trial.

End points

Primary end point of the trial was the time (days) from hospital admission to clinical stability, as described elsewhere.5 Clinical stability was measured daily during hospitalisation. Secondary end points were serum concentrations of inflammatory cytokines (C reactive protein, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and IL-10) and partial pressure of arterial oxygen/fractional inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) at 48 h after treatment administration. Similarly, aminotransferases and total creatine kinase were determined at 48 h after admission to evaluate the potential toxicity of treatment.

To determine the cytokine concentrations, 10 mL of venous blood was obtained within 24 h of hospital admission and after 48 h. Samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature. The serum was separated, divided into aliquots and frozen at −80°C within 6 h of extraction. For analysis, serum was thawed and TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 serum concentrations quantified by Invitrogen Human ELISA kits (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

In the original analysis, we calculated the sample size on the hypothesis that simvastatin could reduce the time to reach clinical stability by 1.5 days. With a reference time to reach clinical stability of 5 days, we calculated that 175 patients were needed in each group to detect this difference with a power of 80% and a type 1 error of 5% (two sided).

Categorical variables were described using counts and percentages. Continuous variables were expressed as the median and IQR. Baseline data between the two study groups were compared by means of the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data and by the χ2 test for categorical data. For 2×2 tables in which cells contained fewer than five observations, Fisher's exact two-tailed test for categorical data was used. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare two related measurements. In addition, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the cytokines values at 48 h in the two groups, adjusting for baseline values.

Data for the end point was analysed on intention-to-treat analysis. A p Value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All reported p values are two tailed. All statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS (V.15.01s) for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

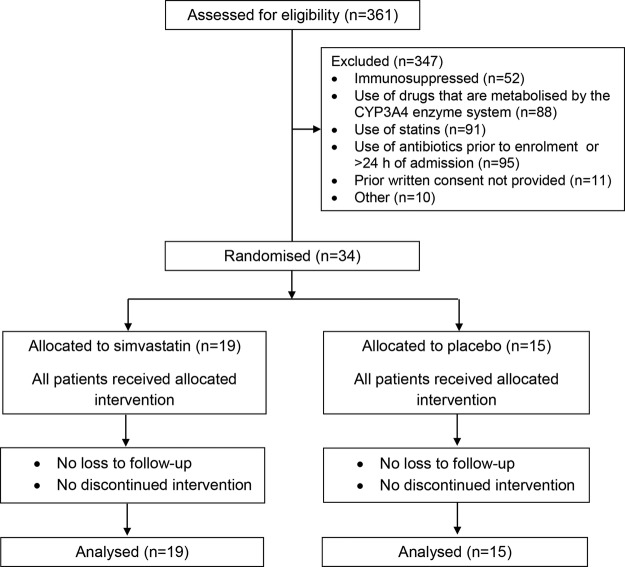

The screening for inclusion criteria was started in December 2009 and ended in June 2011 due to slow recruitment because of the exclusion criteria of the study. Most excluded patients were receiving statins, other drugs that are metabolised by the CYP3A4 enzyme system or antibiotic therapy prior to enrolment. Thirty-four patients were randomly assigned and included in an intention-to-treat analysis for the end point (19 to the simvastatin group and 15 to the placebo group). Figure 1 shows the study profile. The baseline characteristics of the patients at the time of enrolment were similar in the two groups and are detailed in table 1. No significant differences between groups were documented in the clinical features and severity of patients, the aetiology of CAP, and the type of empirical antibiotic therapy and the time since hospital admission to antibiotic administration.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to study groups

| Simvastatin n=19 |

Placebo n=15 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||

| Age, median (IQR), years | 63 (44.5–79) | 76 (45.5–78) |

| Male sex | 14 (73.7) | 12 (80) |

| Current smoker | 4 (21.1) | 4 (26.7) |

| Comorbidities* | 12 (63.2) | 9 (60) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1 (0–1.5) | 1 (0–1) |

| Clinical features | ||

| Impaired consciousness | 2 (10.5) | 2 (13.3) |

| Hypotension | 1 (5.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Hypoxaemia | 12 (63.2) | 9 (60) |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 6 (31.6) | 5 (33.3) |

| Leucocytosis (leucocytes >12 109/L) | 14 (73.7) | 8 (53.3) |

| IDSA/ATS criteria for ICU admission1 | 4 (21) | 5 (33.3) |

| CAP-specific scores | ||

| High-risk PSI classes | 8 (42.1) | 8 (53.3) |

| Aetiology† | ||

| All | 11 (57.9) | 11 (73.3) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 8 (42.1) | 8 (53.3) |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 0 (0) | 2 (13.3) |

| Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (6.7) |

| Time to antibiotic administration, median (IQR), hours | 5.5 (3–8) | 5 (4–7.5) |

| Treatment at admission | ||

| Corticosteroids | 8 (42.1) | 4 (26.7) |

| β-lactams | 15 (78.9) | 12 (80) |

| Quinolones | 15 (78.9) | 9 (60) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

Data are reported as n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

*Comorbidities included chronic pulmonary diseases, chronic heart diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, dementia and cerebrovascular disease.

†Other aetiologies in the simvastatin group were Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae (one case of each).

ATS, American Thoracic Society; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; PSI, pneumonia severity index.

No significant differences in the time from hospital admission to clinical stability were found between study groups (median 3 days, IQR 2–5 vs 3 days, IQR 2–5; p=0.47).

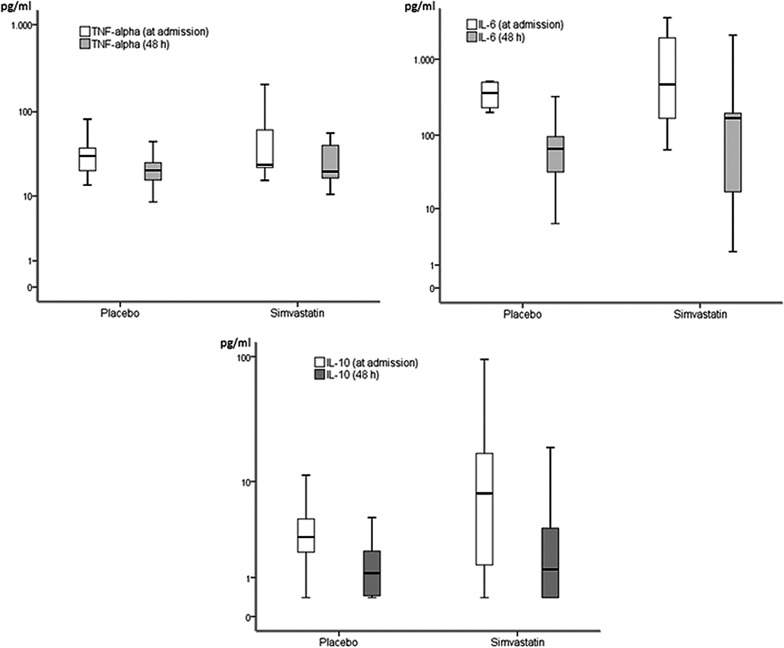

Table 2 compares serum cytokine concentrations and PaO2/FiO2 in the two groups. No significant differences in TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10, C reactive protein and PaO2/FiO2 levels at admission and at 48 h of hospitalisation were found between simvastatin and placebo. However, there were significant changes in cytokine levels at admission compared with those at 48 h during hospitalisation in each group (figure 2). The median change from baseline to 48 h of PaO2/FiO2 and cytokines between study groups did not differ significantly (table 3). A post hoc subgroup analysis in patients with and without corticosteroids did not find significant differences among cytokines in the study groups (data not shown).

Table 2.

Serum cytokine concentrations and PaO2/FiO2 on enrolment and at 48 h during hospitalisation according to study groups

| Simvastatin n=19 |

Placebo n=15 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within 24 h of admission | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 | 276.1 (261–299) | 276.3 (243–320) | 0.90 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 24 (22.3–61.7) | 30.6 (20.5–38) | 0.96 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 700 (171–1908) | 362 (239–515) | 0.91 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 8.35 (1.5–38.8) | 3.2 (2.4–8.3) | 0.17 |

| At 48 h during hospitalisation | |||

| PaO2/FiO2* | 300 (285–374) | 338.1 (314–401) | 0.37 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 151.2 (59.5–243.6) | 69.4 (27.5–212.2) | 0.23 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL)* | 19.9 (16.7–40.8) | 20.6 (15.8–25.5) | 0.58 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL)* | 141 (8–192) | 66 (37.5–97) | 0.64 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL)* | 1.31 (0.4–3.8) | 1.16 (0.45–2.2) | 0.61 |

CRP levels at baseline were not available.

*p Values for ANCOVA analysis for PaO2/FiO2, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-10 were 0.33, 0.97, 0.31 and 0.55, respectively. Data are reported as median (IQR).

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CRP, C reactive protein; FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; IL, interleukin; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Figure 2.

Changes in the cytokine concentrations at admission compared with those at 48 h during hospitalisation in each study group. Concentrations are shown in a logarithmic scale (y axis). All cases, Wilcoxon signed-rank test p<0.001 (IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor).

Table 3.

Median change of serum cytokine concentrations and PaO2/FiO2 from baseline to 48 h between study groups

| Simvastatin n=19 |

Placebo n=15 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PaO2/FiO2 | −25.4 (0 to −68.6) | −64.7 (15.5 to −173.3) | 0.37 |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 5.1 (3.9–14.4) | 10.2 (3.2–13.9) | 0.64 |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 463 (45.5–1579.5) | 354 (169.5–413.5) | 0.87 |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 4.1 (1.1–12.5) | 1.8 (0.6–2.9) | 0.14 |

Data are reported as median (IQR).

FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen; IL, interleukin; PaO2, partial pressure of arterial oxygen; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Transaminase (alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase) and total creatine kinase levels were similar in the simvastatin and placebo groups at 48 h of hospitalisation (table 4). One patient (in the simvastatin group) required ICU admission and one patient died (in the placebo group).

Table 4.

Adverse events during hospitalisation according to study groups

| Adverse event | Simvastatin n=19 |

Placebo n=15 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST level, median (IQR), (ukat/L) | 0.25 (0.22–0.36) | 0.7 (0.3–0.94) | 0.08 |

| AST>2 times upper reference limit | 1 (5.2%) | 3 (20%) | 0.30 |

| ALT level, median (IQR), (ukat/L) | 0.28 (0.22–0.43) | 0.68 (0.3–1.0) | 0.19 |

| ALT>2 times upper reference limit | 2 (10.5%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 |

| CK level, median (IQR), (ukat/L) | 0.87 (0.51–2.22) | 0.60 (0.32–2.7) | 0.53 |

| CK>2 times upper reference limit | 1 (5.2%) | 1 (6.6%) | 1 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CK, creatine kinase.

Discussion

This is a prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the use of statins in patients with CAP. We were unable to find that the use of 20 mg of simvastatin, once daily for 4 days in addition to the usual care, reduces the time from hospital admission to clinical stability and the concentrations of inflammatory cytokines in hospitalised patients with CAP.

No prior randomised study has evaluated the effect of statins on inflammatory cytokine levels or clinically relevant outcome parameters in hospitalised patients with CAP. Observational studies including prior users of the drug have related statin therapy with better outcomes in patients with CAP.10–12 However, an observational study14 suggested that the healthy user bias has a significant role as a confounding factor in the results. Certainly, the limitations of studies of this kind do not allow the application of their findings in clinical practice.

In a recent study involving adult intensive care patients with different infections and severe sepsis (mainly lung, urinary and intra-abdominal infections), the investigators did not find differences in IL-6 concentrations between atorvastatin (20 mg daily) and placebo groups.15 Importantly, another study did not support a beneficial effect of continuing pre-existing statin therapy (atorvastatin 20 mg daily) on sepsis and inflammatory parameters in patients with presumed infection16; no significant differences in IL-6 and C reactive protein decreases were documented at any follow-up time-point in either study group. However, a randomised study in patients with acute bacterial infections found that statin therapy (40 mg of simvastatin, followed by 20 mg of simvastatin) was associated with a reduction in the levels of inflammatory cytokines.17 A post hoc analysis of the subgroup of 48 patients with pneumonia revealed a significant decrease in IL-6 levels, but not in TNF-α levels. Nevertheless, it should be noted that IL-6 levels increased at 72 h in the placebo group. Moreover, a randomised trial found that the acute administration of 40 mg of atorvastatin daily in patients with sepsis may prevent sepsis progression.18 The authors postulated that statins may modulate the pathophysiology of sepsis, thereby restoring endothelial integrity and thus blocking one of the mechanisms in the development of multiorgan failure. Notably, inflammatory cytokines were not evaluated. Finally, a recent study documented that rosuvastatin did not improve clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome.19

Our study suggests that simvastatin does not exert an effect on inflammatory cytokine levels in hospitalised patients with CAP. We evaluated the change in cytokine concentrations within the patient, and between simvastatin and placebo groups. The cytokine concentrations decreased rapidly during the first days of hospital admission in both study groups, and no significant differences were documented at 48 h in cytokine levels between simvastatin and placebo groups. However, cytokine levels were quantified only at baseline and at 48 h, which limits the assessment of statin effects on the further course of the inflammatory response. In addition, it is possible that higher doses of simvastatin17 or the use of other statins18 could have produced different results. A 20 mg dosage was selected to address concerns regarding potential toxicity. Interestingly, in a caecal ligation and perforation model of sepsis in mice, Merx et al20 documented that anti-inflammatory properties vary between individual statins.

Among the strengths of this study is the fact that the treatment was assigned on a random basis. Another unique feature of this trial was that it addressed the question of de novo statin use only in hospitalised patients with CAP. In this regard, a recent study documented major differences in the early status of the immune system in relation to the underlying type of infection and concluded that therapeutic immunointerventions may be directed by the nature of infection.21 In addition, importantly, our study suggest the safety profile of simvastatin in this context. However, it should be noted that patients receiving certain drugs that are metabolised by the CYP3A4 enzyme system were excluded. This is because of the increased risk of rhabdomyolysis during concomitant use of simvastatin, a CYP3A4 substrate statin and CYP3A4 inhibitors,22 and legal aspects related to the responsibility insurance of the study.

Moreover, there are certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the trial did not achieve its recruitment target for determining the effects of statins on time to reach clinical stability. Nevertheless, previous studies faced similar recruitment problems when conducting sepsis-related searches. Second, only systemic cytokine measurements were performed in our study, and this response might differ from that encountered in the lung. Similarly, biomarkers for evaluating coagulation or cardiovascular dysfunction were not evaluated. In addition, other potential benefits of statins in CAP were not assessed in the present study, including stabilisation of the cardiovascular system to avoid acute cardiac events and their potential antiviral and antibacterial effects. Third, some baseline characteristics, such as corticosteroid use and long time to first antibiotic dose may complicate analysis of cytokine levels. However, no significant differences were observed between study groups regarding these topics. Finally, although our study population is representative of patients hospitalised with CAP since the clinical features were similar to those reported in other studies, the exclusion criteria are important limitations to the external validity of the results. In addition, a clinical trial designed with the exclusion criteria used in the present study is likely difficult, mainly due to the need to recruit an adequate number of patients.

In summary, we did not find that adding simvastatin, at a dose of 20 mg daily for 4 days, to the usual treatment of hospitalised patients with CAP decreases the time from hospital admission to clinical stability and the inflammatory cytokine levels. Owing to the difficulty of recruiting patients without exclusion criteria, multicentre randomised studies are needed to determine the precise role of statins on clinically relevant outcome parameters in patients with this infection.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JC designed the study. DV, CG-V, AFS, JD and FL conducted the patient inclusion, reviewed all cases, collected patient information and compiled the data files. MM and FM-R collected, processed and compiled the laboratory data. DV, CG-V and AFS performed the statistical analyses. JC, DV and AFS drafted the paper. JD, MM and FM-R contributed to critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript. JC and DV are the guarantors.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria de la Seguridad Social (grant 07/0864) and Spain's Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad, Instituto de Salud Carlos III—cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund ‘A way to achieve Europe’ ERDF, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (REIPI RD12/0015).

Competing interests: DV is the recipient of a research grant from the REIPI. CG-V is the recipient of a Juan de la Cierva research grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. AFS is the recipient of a research grant from the IDIBELL—Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Hospital Research Ethics Committee (AC099/08) and The Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. IDSA/ATS consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72. 10.1086/511159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA et al. Prognosis and outcomes of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1996;275:134–41. 10.1001/jama.1996.03530260048030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosón B, Carratalà J, Dorca J et al. Etiology, reasons for hospitalization, risk classes, and outcomes of community-acquired pneumonia in patients hospitalized on the basis of conventional admission criteria. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:158–65. 10.1086/321808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez A, Lisboa T, Blot S et al. Mortality in ICU patients with bacterial community-acquired pneumonia: when antibiotics are not enough. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:430–8. 10.1007/s00134-008-1363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA 1998;279:1452–7. 10.1001/jama.279.18.1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menéndez R, Martinez R, Reyes S et al. Stability in community-acquired pneumonia: one step forward with markers? Thorax 2009;64:987–92. 10.1136/thx.2009.118612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellum JA, Kong L, Fink MP et al. Understanding the inflammatory cytokine response in pneumonia and sepsis. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1655–63. 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Serrano S, Dorca J, Coromines M et al. Molecular inflammatory responses measured in blood of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003;10:813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Gudiol F et al. Statins for community-acquired pneumonia: current state of the science. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:143–52. 10.1007/s10096-009-0835-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalmers JD, Singanayagam A, Murray MP et al. Prior statin use is associated with improved outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2008;121:1002–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomsen RW, Riis A, Kornum JB et al. Preadmission use of statins and outcomes after hospitalization with pneumonia: population-based cohort study of 29,900 patients. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2081–7. 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mortensen EM, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA et al. Impact of statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality of subjects hospitalised with pneumonia. Eur Respir J 2008;31:611–7. 10.1183/09031936.00162006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243–50. 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Eurich DT et al. Statins and outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with community acquired pneumonia: population based prospective cohort study. BMJ 2006;333:999 10.1136/bmj.38992.565972.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kruger P, Bailey M, Bellomo R et al. ; The ANZ-STATInS Investigators—ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. A multicentre randomised trial of atorvastatin therapy in intensive care patients with severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:743–50. 10.1164/rccm.201209-1718OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruger PS, Harward ML, Jones MA et al. Continuation of statin therapy in patients with presumed infection: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:774–81. 10.1164/rccm.201006-0955OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novack V, Eisinger M, Frenkel A et al. The effects of statin therapy on inflammatory cytokines in patients with bacterial infections: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1255–60. 10.1007/s00134-009-1429-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel JM, Snaith C, Thickett DR et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 40 mg/day of atorvastatin in reducing the severity of sepsis in ward patients (ASEPSIS Trial). Crit Care 2012;16:R231 10.1186/cc11895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Truwit JD, Bernard GR, Steingrub J et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Trials Network. Rosuvastatin for sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2191–200. 10.1056/NEJMoa1401520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merx MW, Liehn EA, Graf J et al. Statin treatment after onset of sepsis in a murine model improves survival. Circulation 2005;112:117–24. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gogos C, Kotsaki A, Pelekanou A et al. Early alterations of the innate and adaptive immune statuses in sepsis according to the type of underlying infection. Crit Care 2010;14:R96 10.1186/cc9031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowan C, Brinker AD, Nourjah P et al. Rhabdomyolysis reports show interaction between simvastatin and CYP3A4 inhibitors. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:301–9. 10.1002/pds.1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.