Abstract

Background

Prehospital care provided by specially trained, physician-based emergency services (P-EMS) is an integrated part of the emergency medical systems in many developed countries. To what extent P-EMS increases survival and favourable outcomes is still unclear. The aim of the study was thus to investigate ambulance runs initially assigned ‘life-saving missions’ with emphasis on long-term outcome in patients treated by the Mobile Emergency Care Unit (MECU) in Odense, Denmark

Methods

All MECU runs are registered in a database by the attending physician, stating, among other parameters, the treatment given, outcome of the treatment and the patient's diagnosis. Over a period of 80 months from May 1 2006 to December 31 2012, all missions in which the outcome of the treatment was registered as ‘life saving’ were scrutinised. Initial outcome, level of competence of the caretaker and diagnosis of each patient were manually established in each case in a combined audit of the prehospital database, the discharge summary of the MECU and the medical records from the hospital. Outcome parameters were final outcome, the aetiology of the life-threatening condition and the level of competences necessary to treat the patient.

Results

Of 25 647 patients treated by the MECU, 701 (2.7%) received prehospital ‘life saving treatment’. In 596 (2.3%) patients this treatment exceeded the competences of the attending emergency medical technician or paramedic. Of these patients, 225 (0.9%) were ultimately discharged to their own home.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that anaesthesiologist administrated prehospital therapy increases the level of treatment modalities leading to an increased survival in relation to a prehospital system consisting of emergency medical technicians and paramedics alone and thus supports the concept of applying specialists in anaesthesiology in the prehospital setting especially when treating patients with cardiac arrest, patients in need of respiratory support and trauma patients.

Keywords: INTENSIVE & CRITICAL CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study demonstrates that the competences required to perform lifesaving interventions in a large urban population to a large extent are competences outside the competences of an ordinary emergency medical technician or paramedic but inside the curriculum of an attending anaesthesiologist.

A considerable strength of the present study is the sample size and the small number of patients lost to follow-up.

This paper demonstrates that the survivors are distributed within two distinct groups: One group containing patients, who, following a lifesaving intervention are discharged to their own homes in good condition and one group containing patients who, following an initial lifesaving effort die at the hospital. Only a small amount of patients recover in poor or moderately disabled condition.

A considerable weakness of the study is that there is no formal validation whether the ‘life-saving intervention’ was truly needed. It is possible that some of the patients would have survived transport to the hospital without intubation and controlled ventilation, without repetitive injections of vasopressors or without removal of foreign bodies in the airways.

Introduction

Physician-based prehospital emergency services (P-EMS) are established in many developed countries.1 2 The value of such services is debated and is difficult to assess scientifically.3 4 Although no-one questions the value of physicians inside the hospital, ideally, the value of P-EMS should be addressed based on the context in which the service operates, both demographically, geographically and economically, as it has proven difficult to ascertain a positive relationship between the emergency care providers’ level of competence and the outcome of the patient.5 In the region of Southern Denmark, the competences of the emergency medical technicians (EMTs) are restricted to inhalational therapy with broncholytics, rectal administration of benzodiazepines, administration of intravenous glucose, intramuscular administration of naloxone, initial treatment of patients with myocardial infarction (thrombolytic agents, opioids, nitroglycerine), intramuscular adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis as well as fluid administration and defibrillation. The competences of the paramedics (PM) mainly exceeds those of the EMT in the possibility of intravenous administration of epinephrine and amiodarone in ventricular fibrillation as well as intravenous administration of furosemide. The basic response to a request for prehospital assistance is an ambulance manned with two EMTs. According to the perceived severity of the task presented to the dispatch centre, in lesser populated areas of the region, a paramedic is dispatched along with the ambulance in order to supplement the treatment. On 1 May 2006, a Mobile Emergency care Unit (MECU) was initiated in Odense, Denmark. This consists of a rapid-response car operating all year round. It is manned with a physician specialist in anaesthesiology and an EMT. It operates as a part of a two-tiered system, in which the MECU supplements an ordinary ambulance manned with two EMTs.

On inauguration of the MECU in Odense, Denmark in 2006, two questions were posed:

Does the attendance of a specialised physician at the scene make a difference to the patients’ survival compared with the survival procured by the attending EMT or PM?

and

Does a presumed increase in patients resuscitated prehospitally as a result of the presence of a physician manned emergency care unit lead to a large number of resuscitated patients suffering from cerebral sequelae?

The aims of the present study were to investigate these two questions in relation to patients attended to by the MECU in Odense, Denmark, in whom the mission outcome was registered as lifesaving.

In order to study this subject, in each lifesaving mission we investigated whether the competences required to resuscitate the patient or prevent the patient from dying fell within the competences of the attending EMT or PM or whether the competences applied lay within the competences of the attending physician. In each mission, the final outcome of the patient was also sought in order to establish whether the patient's outcome was good, moderate or poor.

Methods

Description of study context

The MECU covers an area of approximately 2.500 square km and serves a population of 250000 to 400000 depending on time of day.

In a typical year, the MECU handles 4900 calls (13.5 calls per day). Owing to apparent overtriage at the dispatch centre, in 13–20% of the calls, the patient can be adequately treated within the competences of the EMT and the ambulance thus waives the MECU en route following initial contact with the patient. As a result of coincident requests for MECU assistance, 3.2–6.1% of the requests are left unanswered.

The MECU is dispatched either by the dispatch centre on the basis of the information given by the caller or by request from the EMTs on the primary ambulance. From its inauguration in 1 May 2006 to 30th April 2011, the dispatch of the MECU was based on the criteria for dispatching the MECU along with an ambulance as seen in box 1. From 1 May 2011 and during the rest of the study period, a criteria-based nationwide Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) system was used.6

Box 1. MECU (Mobile Emergency Care Unit) Dispatch criteria in parts of the observation period.

Ambulance+MECU

Life-threatening conditions

Sudden loss of consciousness

Absence of breathing

Noisy or otherwise impaired breathing

Possible life-threatening conditions

Dyspnoea

Severe chest pain

Sudden onset of serious headache

Impaired breathing in infants and children

Suspected serious illness in children or infants

Sudden onset of severe oral or rectal bleeding

Sudden onset of bleeding in pregnant women beyond 20th gestational week

Accidents implying a risk of life-threatening conditions

Motorway accidents

On highways

High-velocity car crash

Entrapment

Roll-over

Lorry or bus involved

Motorcycle involved

Pedestrian against car/motorcycle

Other accidents

Fall from heights

Entrapped persons

Accidents with bleeding victims

Accidents involving horses

Gunshot or stab wounds towards torso, neck, head

Hanging

Drowning

Burns involving face or exceeding 20% (adults) or 10% (infants and children) of body surface area

Accidents involving trains or airplanes

Fire implying a risk of damage to people

Chemical exposure

Following each MECU run, patient characteristics (including the patient's Civil Registration System number (or Social Security Number), forming a unique identification of the patient),7 the tentative patient diagnosis and the treatment administered, are entered into the MECU database. The physician responsible for the treatment also assesses the immediate prehospital outcome of the patient. This assessment is graded into seven categories:

Patient's condition improved during treatment;

Patient's condition significantly improved during treatment;

Patient undergoing lifesaving procedures;

Patient unchanged;

Patient deteriorating;

Patient dead during treatment;

Others.

Design

The study is a retrospective, descriptive study approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal numbers 2010-41-5097 and 2013-41-2439). Within an 80 month period (1 May 2006 to 31 December 2012), all records at the MECU concerning patients with the outcome ‘Patient undergoing life-saving procedures’ were sought. The medical records and the discharge letters from Odense University Hospital pertaining to these patients were then sought in the hospital's patient registry database according to the patients’ Civil Registration System number.

All records were thoroughly read by the investigators and an audit was performed in each case to validate the immediate prehospital outcome determined by the treating physician. Patients were followed until either discharge to home, discharge to nursing home or death at hospital. On the basis of the information available in the MECU record and the in-hospital medical records and discharge letter, all authors independently agreed on the validity of the claim Patient undergoing ‘life-saving procedures’.

In case of disagreement, agreement was obtained following closer examination of each case.

In case of missing discharge letter from the hospital, or transfer to another hospital the patient was considered lost-to-follow-up.

In all cases registered as ‘Patient undergoing life-saving procedures’, the competences required to save the patient's life was assessed by the authors. On this assessment it was decided whether the competences required to save the patient lay within the competences of the attending PM or EMT or whether the competences required exceeded the competences of the PM or EMT.

Criteria for denoting a case ‘Patient undergoing life-saving procedures’ within the competences of the physician were:

Explicit criteria

Intubation or other airway procedure exceeding the competences of PM or EMTs.

Advanced medical treatment exceeding the competences of PM or EMTs in cardiac arrest and/or defibrillation when indicated by the attending physician.

Implicit criteria

Advanced medical treatment exceeding the competences of the attending PM in severe shock states.

Fluid resuscitation exceeding the competences of the EMT or PM in cases of severe hypovolaemia.

In assessing the criteria and denoting a case ‘life saving within the competences of an EMT or paramedic’ no account was taken whether the interaction saving the patient's life or preventing death had in fact been carried out by the EMT or PM or an attending physician. If the interaction deemed necessary to save the patient's life lay within the curriculum of the EMT or PM, the life-saving effort was considered within the competences of the EMT or PM. Even if a physician had performed bag-mask ventilation and administrated naloxone to a patient with an opioid overdose, the effort was registered as ‘life saving within the competences of the EMT or PM’ as both of these competences lie within the curriculum of the EMT and PM. Likewise, the administration of oxygen, furosemide and nitroglycerine in a patient with severe pulmonary oedema was considered within the competences of an EMT or PM. Only if intubation or non-invasive ventilation with continuous positive airway pressure had been applied, the effort was considered lifesaving requiring competences exceeding the competences of the EMT or PM.

All data were categorised using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA).

Statistical methods

Demographic data are presented as mean and range. All other data were analysed using non-parametric statistics (χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis; IBM SPSS Statistics V.22, Armonk, New York, USA). Differences were considered significant when p<0.05. Bonferroni's correction for repeated measurements was performed comparing physician supervised resuscitation with EMT-directed resuscitation and PM-directed resuscitation.

Results

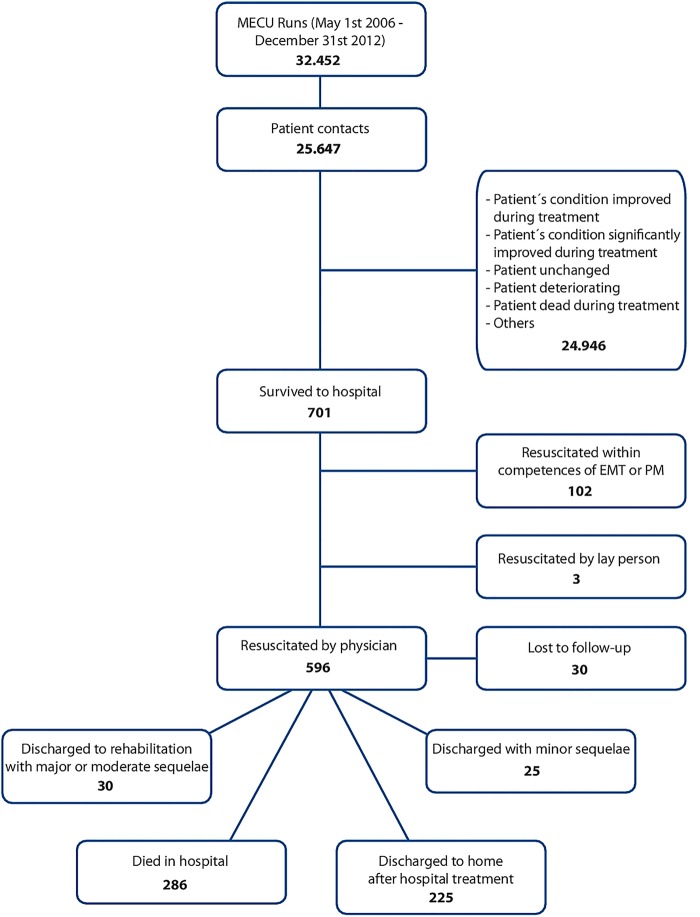

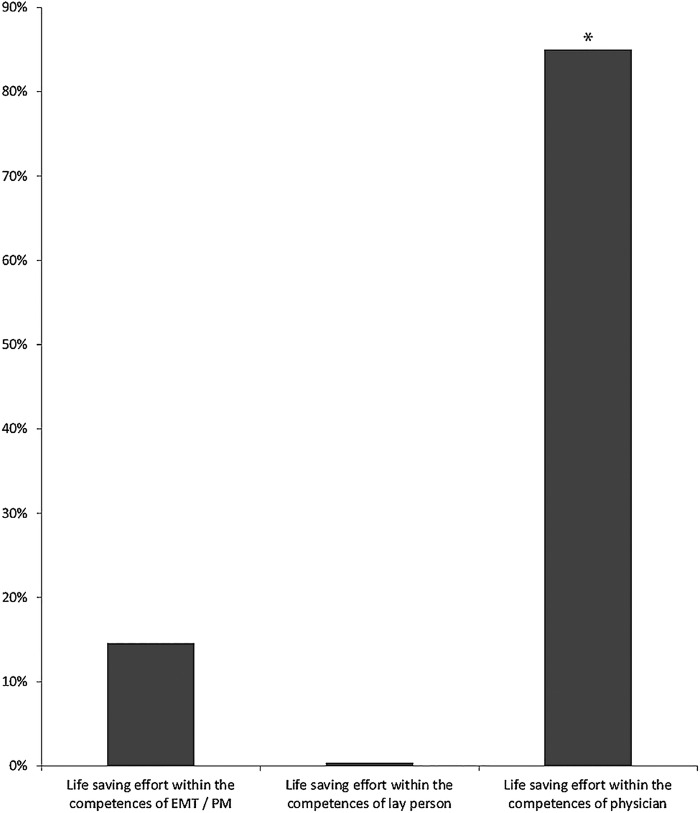

A total of 32 452 runs were recorded for the MECU during the study period; 25 647(79%) of these runs resulted in contact with a patient. 701 of these patients received prehospital ‘life saving treatment’. In 102 patients the treatment necessary to save the patient's life was administered within the competences of the attending EMT or PM (typical treatment modalities: mask ventilation followed by injection of naloxone, injection of glucagon or intravenous glucose, administration of defibrillation with return of spontaneous circulation and breathing). Three patients were resuscitated within the competences of lay persons (in all three cases administration of defibrillation using an automatic external defibrillator resulting in return of spontaneous circulation, breathing and return of consciousness). A total of 596 patients were subjected to lifesaving interventions performed by the attending physician. This difference from the number of patients resuscitated within the competences of the EMT or PM is highly significant (p<0.001).

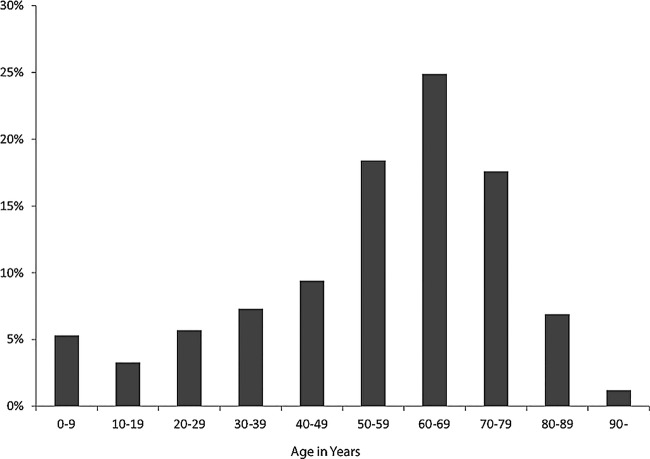

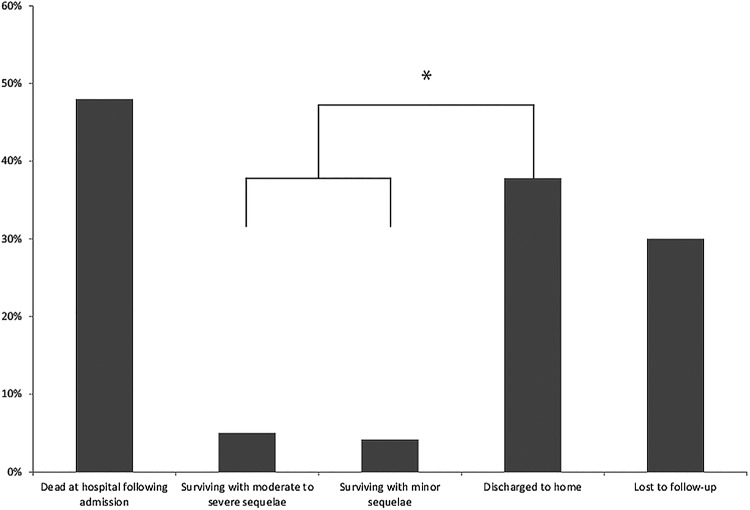

Of the 596 patients subjected to lifesaving interventions performed by the attending physician, 286 patients (48%) died at the hospital during the admission. Thirty patients were discharged to rehabilitation clinics or other hospitals with major or moderate sequelae, these sequelae consisting primarily of cerebral impairment. Twenty-five patients were discharged with minor sequelae stemming primarily from the musculoskeletal system requiring occupational therapy. Compared with patients surviving with sequelae, a significant majority—225 patients in all (37.8%)—were discharged to their own homes following in-hospital treatment (p<0.001). The mean age of patients resuscitated within the competences of an anaesthesiologist was 54.3 years (range 0–91). The number of patients suffering minor or moderate sequelae or severe sequelae did not differ (p=0.39) (figures 1–4). No differences in the number of survivors were found comparing each year (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the patients.

Figure 2.

Distribution of patients resuscitated within the competences of emergency medical technician/paramedic, lay person and anaesthesiologist. *p<0.001 (Patients resuscitated within the competences of anaesthesiologists vs patients resuscitated within the competences of the emergency medical technician/paramedic).

Figure 3.

Age distribution of survivors discharged to home following resuscitation by anaesthesiologist.

Figure 4.

Outcome of patients resuscitated at the scene by anesthesiologists. *p<0.001 (Discharged to home vs Surviving with minor or moderate to severe sequelae).

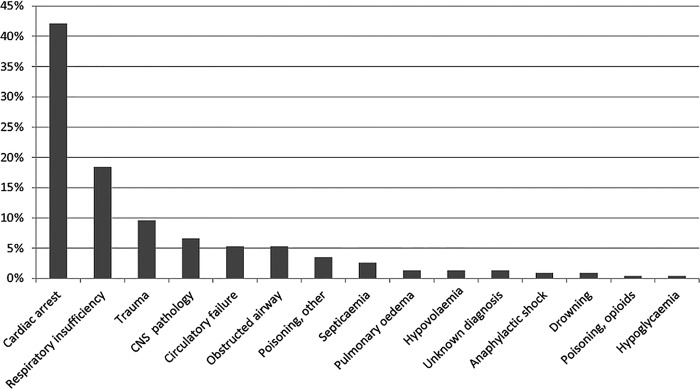

The diagnoses of the patients that were discharged to their own homes following an incident requiring lifesaving competences exceeding the competences of an attending EMT or PM are shown in figure 5.

Figure 5.

Diagnoses in patients discharged to their homes following anaesthesiologist supervised resuscitation.

No valid account of the age distribution of patients receiving prehospital lifesaving treatment within the competences of the EMT or PM can be given. Within this group of patients a large number of drug addicts are found. These patients generally left the scene following successful treatment with naloxone by the EMT or PM and were not always identified.

In all, 17 patients were lost to follow-up. These patients were primarily foreign citizens transferred to hospitals outside of Denmark. Thirteen patients were transferred to other Danish hospitals before the patients’ final outcome could be established.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the presence of an anaesthesiologist manned mobile emergency care unit results in a large number of patients receiving prehospital life-saving treatment exceeding the competences of the EMTs or PMs.

When a traumatised or critically ill patient is brought to the emergency room within the hospital, a specialist is usually called on to treat the patient. However, the benefit gained by utilising specialised physicians in the prehospital service is still somewhat disputed,4 5 8–10 and some countries do not offer advanced prehospital treatment as performed by physicians but rely on EMTs or PMs with varying competences.11 However, while PMs possess a considerable number of competences allowing them to treat a variety of conditions, prehospital physicians possess some additional critical care competences which are potentially lifesaving but are required infrequently and can carry significant risks.12

The availability of advanced prehospital life support (ALS) and basic life support (BLS) differ between countries—as such rendering comparison difficult. Although endotracheal intubation of patients in cardiac arrest recently has been disputed,13 ALS however, seems to improve survival in patients with myocardial infarction while BLS may be the proper level of care for patients with penetrating injuries.8 Papers describing both gains in quality-adjusted life-years as well as increased survival with physician treatment in trauma and, based on more limited evidence, cardiac arrest, have been published.9 10

Some studies indicate a beneficial effect of ALS administered by physicians in patients with blunt head trauma.14–16 All these studies are retrospective in character and further high-quality research in this area would be welcome.17

However, pending results from an ongoing randomised study on the effect on an attending physician versus a PM in treating traumatised patients,18 the best evidence regarding the possible impact of physician-assisted prehospital treatment comes as yet from retrospective studies.

The concept of advanced prehospital treatment should be not attributed to intubation alone, as studies have suggested that advanced life support interventions (eg, intubation) performed by PMs may have harmful effects compared to in-hospital treatment.19 20 Apart from intubation, control of end-tidal CO2 and administration of carefully titrated doses of inotropic agents also forms a part of advanced prehospital treatment. In sepsis, early administration of antibiotics have proven valuable21 and there is no reason to believe that timing of therapy does not also apply to the prehospital scene.

In the present study, we have found that the presence an anaesthesiologist-staffed MECU significantly improves patients’ survival based on an evaluation of the competences required to resuscitate or prevent a critically ill or injured patients from dying. Few patients recovered with moderate or severe sequelae. Our results are probably generalisable to all of Scandinavia as the level of competence of the EMTs or PMs does not differ markedly in the Scandinavian countries and as all Scandinavian countries provide anaesthesiologist-staffed prehospital services.22 All of these services apply advanced emergency medical procedures in critically ill or injured patients, the lowest incidence of these procedures being exercised in Denmark.1 Direct comparison between the USA and Europe, however, is difficult, as the prehospital concept differs. In the USA, the primary prehospital resource is an EMT supported by a PM while the general European prehospital resource consist of a P-EMS supporting a general ambulance.

Our primary finding in this retrospective study is that the vast majority of the life-saving procedures carried out in the MECU in Odense, Denmark is performed within the competences of the attending anaesthesiologist. Another important finding in this study is the outcome pattern of the patients resuscitated within the competences of the physician: approximately half of the patients that survive the incident are discharged to their own homes without major or even moderate sequelae. Another half of the patients die at the hospital. Only a minute fraction of patients that survive a critical incident requiring resuscitation by the anaesthesiologist manning the MECU experience sequelae.

The subject of the present study was the life-saving interventions. However, the MECU is not only a life-saving service: both supervision of EMTs and PMs and clinical decision-making might add value to the combined emergency system. Moreover, utilising a physician in the prehospital environment may actually enable withholding of futile advanced interventions, such as withholding intubation for ethical reasons in patients where such a treatment could be contraindicated is probably beneficial for ethical reasons.23 As such, advanced medical care including intensive care unit admittance might be avoided in futile cases.

Strengths and limitations

Two different criteria systems for dispatch used within the study period. However, the main characteristics of the patient population presumably remained unchanged throughout the study period. First, as the general activity of the MECU was constant throughout the period, and second, because the principles applied in the region are that any ambulance meeting demands that cannot be covered by the EMTs manning the ambulance are requested to summon the MECU for help. Any patient requiring advanced medical assistance thus would presumably be seen by the MECU.

The strength of the present study is the sample size and the small number of patients lost to follow-up. All data have been entered by the anaesthesiologist on call immediately following the mission. All missions assigned the outcome ‘life saving’ have been audited by the authors of whom three are independent of the MECU. The validity of data thus is acceptable. Weaknesses of the present study however, are that the study is a retrospective study. In Scandinavia at the present time, it is not feasible to perform a prospective randomised study on the presence of an anaesthesiologist at the scene. In this study, no comparison has been made with a period without a MECU. The present private ambulance operator in the area does not carry databases extensive enough to support such a study. Follow-up of patients have been reduced to establishing whether the patient was discharged to his/her own home. The study would have benefitted from assessing the patients using post hoc interviews to evaluate their status. However, given our large material and the time span of the investigation making post hoc interviews difficult, in this study, we assumed that a patient being discharged to his/her own home was a patient with favourable outcome.

An important limitation of the present study is the application of a subjective measure of life-saving intervention. This may have given rise to reporting bias as the physician responsible for the mission performed was the one who made the initial assessment of the mission. In our study we have subjected each self-reported case of ‘life saving mission’ to an audit applying both explicit criteria and implicit criteria in order to assess, to what extent any given mission indeed correctly had been determined a lifesaving mission. Furthermore, the large numbers of missions not classified as lifesaving missions indicate a reliable reporting culture.

Finally, one might argue that all therapeutic interventions have been carried out by a specialist in anaesthesiologist at the scene following best standard of care. By definition, the specialist would be deemed negligent if he failed to use his level of skill, knowledge, and care in diagnosis and treatment of patients. Furthermore, it is impossible to validate the claim ‘life saving intervention’ in a formal way: Should one withhold the intervention, the patient would die if the claim that the life-saving intervention was indeed correct.

Conclusion

This retrospective study demonstrates that anaesthesiologist administrated therapy increases the level of treatment modalities leading to an increased survival in relation to a prehospital system consisting of emergency medical technicians and paramedics alone without an unacceptably high number of patients suffering severe sequelae. The present study thus lends firm support to the concept of applying physician specialists in anaesthesiology in the prehospital setting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SM contributed to this manuscript with idea and design as well as acquisition of data, analysis of data and drafting and revising of the manuscript. AJK contributed to this manuscript with idea, design, analysis of data, drafting and revision of the manuscript. STZ contributed to this manuscript with acquisition and analysis of the data, drafting and revising of the manuscript. ACB contributed to this manuscript with idea and design as well as acquisition of data, analysis of data and drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Krüger AJ, Lossius HM, Mikkelsen S et al. Pre-hospital critical care by anaesthesiologist-staffed pre-hospital services in Scandinavia: a prospective population-based study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013;57:1175–85. 10.1111/aas.12181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gries A, Zink W, Bernhard M et al. Realistic assessment of the physician-staffed emergency services in Germany. Anaesthesist 2006;55:1080–6. 10.1007/s00101-006-1051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner EB, Maio RF, Garrison HG et al. Economic value of out-of-hospital emergency care: a structured literature review. Ann Emerg Med 2006;47:515–24. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakalos G, Mamali M, Komninos C et al. Advanced life support versus basic life support in the pre-hospital setting: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2011;82:1130–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stiell IG, Nesbitt LP, Pickett W et al. The OPALS Major Trauma Study: impact of advanced life-support on survival and morbidity. CMAJ 2008;178:1141–52. 10.1503/cmaj.071154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen MS, Johnsen SP, Sørensen JN et al. Implementing a nationwide criteria-based emergency medical dispatch system: a register-based follow-up study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:53–61. 10.1186/1757-7241-21-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen CB. The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:22–5. 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryynänen O-P, Iirola T, Reitala J et al. Is advanced life support better than basic life support in prehospital care? A systematic review. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2010;18:62 10.1186/1757-7241-18-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lossius HM, Søreide E, Hotvedt R et al. Prehospital advanced life support provided by specially trained physicians: is there a benefit in terms of life years gained? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2002;46:771–8. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.460703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bøtker MT, Bakke SA, Christensen EF. A systematic review of controlled studies: do physicians increase survival with prehospital treatment? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2009;7:12 10.1186/1757-7241-17-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer M, Kamp J, Riesgo LGC et al. Comparing emergency medical service systems—a project of the European Emergency Data (EED) Project. Resuscitation 2011;82:285–93. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Vopelius-Feldt J, Benger J. Who does what in prehospital critical care? An analysis of competencies of paramedics, critical care paramedics and prehospital physicians. Emerg Med J 2014;31:1009–13. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg RA, Bobrow BJ. Cardiac resuscitation: is an advanced airway harmful during out-of-hospital CPR? Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10:188–9. 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abbott D, Brauer K, Hutton K et al. Aggressive out-of-hospital treatment regimen for severe closed head injury in patients undergoing air medical transport. Air Med J 1998;17:94–100. 10.1016/S1067-991X(98)90102-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner AA. The role of physician staffing of helicopter emergency medical services in prehospital trauma response. Emerg Med Australas 2004;16:318–23. 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2004.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis DP, Peay J, Serrano JA et al. The impact of aeromedical response to patients with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Ann Emerg Med 2005;46:115–22. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Vopelius-Feldt J, Wood J, Benger J. Critical care paramedics: where is the evidence? A systematic review. Emerg Med J 2014;31:1016–24. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garner AA, Fearnside M, Gebski V. The study protocol for the Head Injury Retrieval Trial (HIRT): a single centre randomised controlled trial of physician prehospital management of severe blunt head injury compared with management by paramedics. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:69 10.1186/1757-7241-21-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bochicchio GV, Ilahi O, Joshi M et al. Endotracheal intubation in the field does not improve outcome in trauma patients who present without an acutely lethal traumatic brain injury. J Trauma 2003;54:307–11. 10.1097/01.TA.0000046252.97590.BE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankema SP, Ringburg AN, Steyerberg EW et al. Beneficial effect of helicopter emergency medical services on survival of severely injured patients. Br J Surg 2004;91:1520–6. 10.1002/bjs.4756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al. Early Goal-Directed Therapy Collaborative Group. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krüger AJ, Skogvoll E, Castrén M et al. Scandinavian pre-hospital physician-manned Emergency Medical Services—Same concept across borders? Resuscitation 2010;81:427–33. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rognas L, Hansen TM, Kirkegaard H et al. Refraining from pre-hospital advanced airway management: a prospective observational study of critical decision making in an anaesthesiologist-staffed pre-hospital critical care service. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:75 10.1186/1757-7241-21-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.