Abstract

Objective

To investigate associations of giving birth with morbidity in terms of hospitalisation and social consequences of morbidity in terms of sickness absence (SA), while taking familial (genetics and shared environmental) factors into account.

Design

Prospective register-based cohort study. Estimates of risk of hospitalisation and SA were calculated as HRs with 95% CIs.

Setting

All female twins, that is, women with a twin sister, born in Sweden.

Participants

5118 Swedish female twins (women with a twin sister), born during 1959–1990, where at least one in the twin pair had their first childbirth (T0) during 1994–2009 and none gave birth before 1994.

Main outcome measures

Hospitalisation and SA during year 3–5 after first delivery or equivalent.

Results

Preceding the first childbirth, the mean annual number of SA days increased for mothers, and then decreased again. Hospitalisation after T0 was associated with higher HRs of short-term and long-term SA (HR for short-term SA 3.0; 95% CI 2.5 to 3.6 and for long-term SA 2.3; 95% CI 1.6 to 3.2). Hospitalisation both before and after first childbirth was associated with a higher risk of future SA (HR for long-term SA 4.2; 95% CI 2.7 to 6.4). Familial factors influenced the association between hospitalisation and long-term SA, regardless of childbirth status.

Conclusions

Women giving birth did not have a higher risk for SA than those not giving birth and results indicate a positive health selection into giving birth. Mothers hospitalised before and/or after giving birth had higher risks for future SA, that is, there was a strong association between morbidity and future SA.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH, childbirth, sick leave, hospitalization

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strengths of the study include the population-based prospective design, using national registers with high completeness and validity.

With a twin study design, we were able to take familial influences into account.

As inpatient care to a great extent has been replaced by outpatient treatment, some of the decrease in hospitalisation over the years is a result of a shift in the responsibility for inpatient care from hospitals to outpatient care facilities.

Introduction

In most countries with high labour force participation, women have higher levels of sickness absence (SA) than men.1–4 Many theories and mechanisms regarding this have been suggested, for example, women having higher morbidity, higher workload (when combining paid and unpaid work), tougher situation on the labour market, men being the norm for how the labour market is organised, gender bias in healthcare and social insurance systems, discrimination, domestic violence, etc.5–9 Another hypothesis behind this gender difference in SA focuses on SA during pregnancy and after childbirth.6 10–13 Several studies show that women have higher SA during pregnancy10 14 and that pregnancy-related SA explains half of the gender differences in SA in fertile ages.15

One of the changes in society that may affect health after childbirth is that the mean age for having the first child has increased over the past years and that women with a higher level of morbidity now give birth. Further, nowadays, the proportion of caesarean sections has increased as well as vacuum extraction deliveries, leading to a risk of later health problems.16 17

In this study, the focus is on childbirth, morbidity and SA among women, to get a better understanding of mechanisms behind SA among women in fertile ages. There are hardly any studies on the associations between giving birth and morbidity and SA, and those conducted have focused on a relatively short time period right after childbirth, most often within the first year following the child delivery,18 19 while prospective studies with longer follow-up of mothers are rare.6 12 20

Pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period may imply large physical, mental and social changes during a short period of time, increasing the risk for disease and injury.21 22 Different types of physical and mental disorders are common during pregnancy and after childbirth—and can in some cases be long standing or even permanent—however, this is hardly studied at all.19 Giving birth may be associated with a higher risk of certain diseases demanding hospitalisation, such as cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, mental disorders and different types of injuries.23–26 For women with a disease present before the childbirth, the disorder might deteriorate after childbirth.23 24 Regarding symptoms related to childbirth, high prevalence has been shown 6 months after childbirth for, for example, low back pain, fatigue, headache and sleep disorders.19 27 Most of these symptoms seem to remain up to 1 year after childbirth.17 Besides physical health effects, depression and other mental disorders have also been linked to childbirth,26 28 but again prospective studies with longer follow-up are lacking.27 Even though having children has been shown to contribute to an overall well-being, this is not the case for everybody and especially not among single mothers whose economic situation and thereby possibilities for good healthcare might be worse.29–31

Morbidity can be measured in different ways, for example, through self-reports or visits to healthcare. We will use data on more severe morbidity that involves assessments from physicians, that is, morbidity that has led to hospitalisation, a measure that has so far not been used in this type of studies. SA is not a good measure of morbidity—most people with morbidity are not on SA.4 Instead, SA is considered a very good measure of social consequences of morbidity, in terms of not being able to support yourself from work.4 Yet there are surprisingly few studies on the association between morbidity and SA, and in media and among some researchers sometimes the level of morbidity among sickness absentees even is questioned, especially for female sickness absentees—their SA is rather considered related to attitudes than to morbidity.12 32 33

Studies examining the role of familial factors (ie, genetic and shared (mainly childhood) environment) on morbidity have shown that genetics tends to explain a moderate to large extent of the variability in most of the chronic diseases.34 35 For example, heritability for mental disorders varies between 30% and 90%,36 whereas genetic factors have been shown to explain 30–60% of the total variation in musculoskeletal disorders.37 38 Taken together, familial factors are important to account for when studying the association between morbidity (here in terms of hospitalisation) and SA as studies otherwise could lead to erroneous conclusions. Twin settings provide a powerful tool for studies of these aspects in research of SA, a research area where different selection biases otherwise might have an impact on results. Twins in a pair are optimally matched on genetic (100% for MZ pairs and on average 50% for DZ pairs) and common environmental factors through childhood (100% for both MZ and DZ twin pairs when reared together) in addition to age and sex (for the same-sexed pairs). An experimental design, which can control for these familial influences, is to examine discordant twin sisters, that is, where one twin sister has given birth and the other has not. If discordant twin sisters show similar associations as the analyses of the whole cohort, this would indicate that the childbirth may actually be a contributing cause of the future SA. If instead the association found among the whole cohort cannot be replicated within discordant twin sisters, then familial factors are of importance. Influence of familial factors (genetic and common environment) is indicated if the association found in the analyses of the whole cohort disappears or changes considerably in the analyses of discordant twin pairs.39

The aim of the study was to investigate the associations of giving birth with subsequent morbidity in terms of hospitalisation and SA. Familial factors (genetics and shared/early environmental) were taken into account in order to assess if familial factors explain a potential association between childbirth and future hospitalisation and SA.

Methods

Participants and data sources

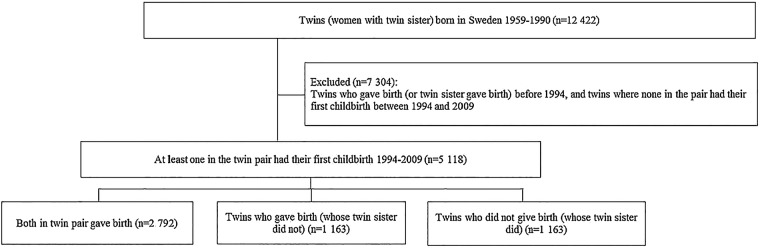

We performed a prospective population-based cohort study of female twins. All female twins, that is, women with a twin sister, born in Sweden between 1959 and 1990 were selected from the Swedish Twin Registry (STR).40 After excluding women who delivered their first child before 1994 or whose twin sister had her first delivery before 1994, and twins where none in the pair had their first delivery between 1994 and 2009 (n=7304), the final cohort comprised 5118 women of which 95% had income from work, the others had income from parental benefits, unemployment benefits, student benefits, different types of sickness benefits or a mixture of those (in the year prior to the birth year, ie, T(−1). All had some of those types of income, all granting rights to SA benefits. The STR is the largest population-based register of twin births in the world, with information such as birth date, sex, zygosity and pair identification.40 41 The selection of the study population is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the study population.

The unique personal identity number assigned to each Swedish resident42 was used to link information from several nationwide population-based registers at an individual level up until 2009 as follows. The Causes of Death Register was used to obtain information on date of death.43 This register contains information on all deceased Swedish residents since 1952. Information on all deliveries (including stillbirths) was derived from the Medical Birth Register, which was established in 1973 and includes information on almost all births in Sweden.44 In order to increase the coverage on delivery, we also used the National Patient Register (NPR) to obtain information on all deliveries. This register was founded in 1964 and includes all individuals admitted to any psychiatric or general hospital.45 Information on hospitalisation with a principal diagnosis for delivery (as defined by the International Classification of Disease (ICD): ICD-9: 650, 651.9, 652.2, 669.5-8; and ICD-10: O80-84) was obtained. The NPR was also used to obtain annual information on other hospitalisations, that is, inpatient care. Annual information on educational level and on SA days was obtained from Statistics Sweden.

Time in relation to childbirth

The studied women were followed in relation to year of first childbirth, referred to as T0. In order to compare those who gave birth with those who did not, T0 for the women who did not give birth was defined as the year of her twin sister's first childbirth.

Hospitalisation

Data on hospitalisation covered the period 6 years prior to, and 6 years after, the year of the first childbirth (T0) or equivalent. For descriptive purposes, the total and the average number of hospitalisation days per year were calculated.

In order to examine if hospitalisation prior to (or after) childbirth increases the risk for future hospitalisation, the first part of the regression analyses considered hospitalisation as both exposure and outcome. We created one dichotomous variable for hospitalisation before T0 (ie, exposure), and two dichotomous outcome variables for hospitalisation during year 3–5 after T0: one for hospitalisation with any diagnosis and one excluding hospitalisation with diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.

In order to answer the research question “Does hospitalization prior to (or after) childbirth increase the risk for future SA?”, we created two dichotomous hospitalisation exposure variables: one for hospitalisation before T0 and one variable: hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0 (excluding diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period).

Sickness absence

SA can be measured in several ways, related to duration and incidence.46 We used the following four measures: total and average number of SA days per year; number of SA days during year 3–5 after T0; and number of SA days >90 sick leave days during year 3–5 after T0.

Sickness insurance in Sweden

In Sweden, all residents aged 16–65 years who have income from work, unemployment benefits, parental benefits or student benefits are entitled to sickness benefits from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, if unable to work due to disease or injury. Among employed individuals, sick pay was in most cases paid by the employer during the first 14 days of a sick leave spell, which means that we do not have data on most of the short sick leave spells. In most of the years studied, there was no limitation to duration of a sick leave spell. Sickness benefits covered 80% of lost income, up to a certain level. All were covered by a healthcare insurance covering the right to hospital care when needed, at a much reduced cost of less than €10 a day. Care during pregnancy and delivery was free.

Potential confounding factor

As research has shown socioeconomic disparities in age at first birth (eg, the higher the education, the later the first birth),47 48 we adjusted for educational level at T0. Years of education was classified into four categories: <9 years of compulsory school, 10–12 years of education (senior high school), ≥13 years of education (college/university), missing.

Statistical analysis

First, Cox proportional hazard models with constant time-at-risk49 were applied to estimate HRs with 95% CIs for having at least one hospitalisation after childbirth (T0). In a first model (model a), adjustments were made for age. Second (model b), additional adjustments were made for delivery year and educational level at time of T0. Thereafter, twin pairs who were discordant with respect to outcomes, that is, having at least one hospitalisation after T0, were analysed using Conditional Cox regression. In the next step, we analysed the associations between childbirth, hospitalisation and SA by fitting three Cox regression models (table 3). The first (model a) was adjusted for birth year. In the second model (model b), additional adjustments were made for delivery year and educational level at time of T0. In the third model (model c), previous hospitalisation was included. Thereafter, twin pairs who were discordant (Conditional Cox regression) with respect to outcomes, that is, having had SA or long-term SA (>90 days), were analysed.

Table 3.

Cox proportional HR with 95% CI for the association between childbirth, hospitalisation and new sickness absence (SA) in year 3–5 after T0, in twins where at least one in the pair had their first childbirth during 1994–2009

| Status childbirth and hospitalisation | SA in year 3–5 after T0 (regardless of the number of days) |

Long-term SA (>90 days) in year 3–5 after T0 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs§, ‡ | Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs¶, ‡ | |

| All women (n=5118) | ||||||||

| No childbirth, no hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) |

| No childbirth, hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 2.7 (1.8 to 4.1) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.4) | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.9) | 4.5 (2.5 to 8.2) | 3.5 (1.9 to 6.2) | 2.8 (1.5 to 5.1) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.3) |

| Childbirth, no hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.5) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.2) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.2) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| Childbirth, hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 3.0 (2.5 to 3.6) | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.9) | 2.4 (2.0 to 2.9) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.6) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.2) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5) | 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

| Women who had at least one childbirth (n=2792) | Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs††,* | Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs‡‡, ‡ |

| No hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) |

| Hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0** | 1.3 (1.2 to 1.5) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.6) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.4) | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) |

Three models for adjustments as well as for discordant twin pairs.

*Adjusted for birth year.

†Model a, and additional adjustments for delivery year and educational level.

‡Model b, and additional adjustments for earlier hospitalisation.

§Twin pairs where one had an SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=835 pairs).

¶Twin pairs where one had a long-term SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=277 pairs).

**Diagnoses O00-O99 excluded.

††Twin pairs where one had an SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=542 pairs).

‡‡Twin pairs where one had a long-term SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=184 pairs).

Finally, in the step where we analysed the association between hospitalisation before and after first childbirth, and subsequent SA (table 4), we adopted the first two models (model a–b) from table 3. In a third model (model c), we fitted an additional model in which adjustments were made for subsequent deliveries.

Table 4.

Cox proportional HR with 95% CI for the association between hospitalisation before and after the first childbirth, and new sickness absence (SA) in year 3–5 after T0, in twins who had their first childbirth during 1994–2009 (n=2792)

| Hospitalisation status before and after childbirth | SA in year 3–5 after T0 (regardless of the number of days) | Long-term SA (>90 days) in year 3–5 after T0 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs§, † | Model a* | Model b† | Model c‡ | Discordant twin pairs¶,† | |

| No hospitalisation either before T0** or during year 1–2 after T0†† | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) |

| Hospitalisation before T0** but not during year 1–2 after T0†† | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.4) | 2.1 (1.5 to 3.1) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.1) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) |

| No hospitalisation before T0** but during year 1–2 after T0†† | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 2.0 (1.5 to 2.8) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.7) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.7) | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.1) |

| Hospitalisation before T0** and during year 1–2 after T0†† | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.5) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.2) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.2) | 4.2 (2.7 to 6.4) | 3.5 (2.3 to 5.3) | 3.5 (2.3 to 5.4) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) |

Three models for adjustments as well as for discordant twin pairs.

*Adjusted for birth year.

†Model a, and additional adjustments for delivery year and educational level.

‡Model b, and additional adjustments for subsequent deliveries.

§Twin pairs where one had an SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=542).

¶Twin pairs where one had a long-term SA during the follow-up and the other did not (n=184).

**During the period 1–5 years prior to T0.

††Diagnoses O00-O99 excluded.

The proportional hazards assumption was checked by including time-dependent versions of all the covariates in the models. This did not indicate a violation of the proportionality assumption.

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS V.9.3 and STATA V.12.1.

The STROBE checklist was used in designing and reporting the study.

Results

Of the 5118 women included in the study, 77% had given birth at least once between 1994 and 2009 (table 1). Of these women, nearly 70% also had given birth later, at least once. A majority of the women who gave birth had their first delivery before the age of 30 (61%). The educational level distribution was rather similar when comparing those who gave birth with those who did not. When hospitalisations with diagnoses for pregnancy and childbirth were excluded, 30% of the women, that is, the 1183 where both in a pair gave birth and the 407 twins where only one in the pair gave birth had at least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years prior to and 6 years after their first delivery (the delivery year excluded). The corresponding rate for the women who had not given birth was 27%. Half of the women who gave birth had at least 1 day of SA during the period 6 years prior to or the 6 years after first delivery, when the year for childbirth was excluded. The majority of the women had no SA at all in the 6 years following childbirth.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics for twins (women with a twin sister) born in Sweden during 1959–1990 (excluding those who gave birth before age 16 and those who died before age 16), where at least one in the pair had their first childbirth during 1994–2009 and none before 1994

| Variables | Both gave birth | Twin pairs where only one in the pair gave birth |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twin 1 (gave birth) | Twin 2 (did not give birth) | |||

| N | 2792 | 1163 | 1163 | 5118 |

| Number of deliveries | ||||

| One delivery | 711 (25%) | 501 (43%) | ||

| Two or more deliveries | 2081 (75%) | 662 (57%) | ||

| Age at T0 (years) | ||||

| 16–19 | 47 (2%) | 33 (2%) | ||

| 20–24 | 511 (18%) | 239 (21%) | ||

| 25–29 | 1150 (41%) | 444 (38%) | ||

| 30–34 | 847 (30%) | 323 (28%) | ||

| 35–39 | 207 (7%) | 109 (9%) | ||

| >40 | 30 (1%) | 15 (1%) | ||

| Zygosity | ||||

| Monozygotic | 1726 (62%) | 608 (52%) | 608 (52%) | 2942 (57%) |

| Dizygotic | 1066 (38%) | 555 (48%) | 555 (48%) | 2176 (43%) |

| Highest attained education* (years) | ||||

| ≤9 | 179 (6%) | 74 (6%) | 55 (5%) | 308 (6%) |

| 10–12 | 1434 (51%) | 608 (52%) | 621 (53%) | 2663 (52%) |

| ≥13 | 1173 (42%) | 474 (41%) | 422 (36%) | 2069 (40%) |

| Information on education missing | 6 (0%) | 7 (1%) | 65 (6%) | 78 (2%) |

| Hospitalisation† | ||||

| At least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years prior through 6 years after T0 | 2161 (77%) | 703 (60%) | 325 (28%) | 3189 (62%) |

| At least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years prior through 6 years after T0 (excluding hospitalisations with a diagnosis for pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium) | 865 (31%) | 315 (27%) | 314 (27%) | 1494 (29%) |

| At least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years prior through 6 years after T0 (excluding hospitalisations with a diagnosis for pregnancy, and childbirth) | 1183 (42%) | 407 (35%) | 325 (28%) | 1915 (37%) |

| At least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years prior to T0 | 679 (24%) | 251 (22%) | 217 (19%) | 1147 (22%) |

| At least one hospitalisation during the period 6 years after T0 | 1965 (70%) | 585 (50%) | 168 (14%) | 2718 (53%) |

| At least one hospitalisation both before and after T0 | 483 (17%) | 133 (11%) | 60 (5%) | 676 (13%) |

| SA‡ | ||||

| At least one SA during the period 6 years prior through 6 years after T0 | 1526 (55%) | 530 (46%) | 365 (31%) | 2420 (47%) |

| At least one SA during the period 6 years prior to T0 | 690 (25%) | 274 (24%) | 224 (19%) | 1188 (23%) |

| At least one SA during the period 6 years after T0 | 1245 (45%) | 382 (33%) | 221 (19%) | 1848 (36%) |

T0 is defined as the year for first childbirth for women who gave birth, and as the year of the twin sister's childbirth for those who did not give birth.

*At the time of T0.

†Excluding hospitalisations occurring during T0.

‡Excluding SA occurring during T0.

SA, sickness absence.

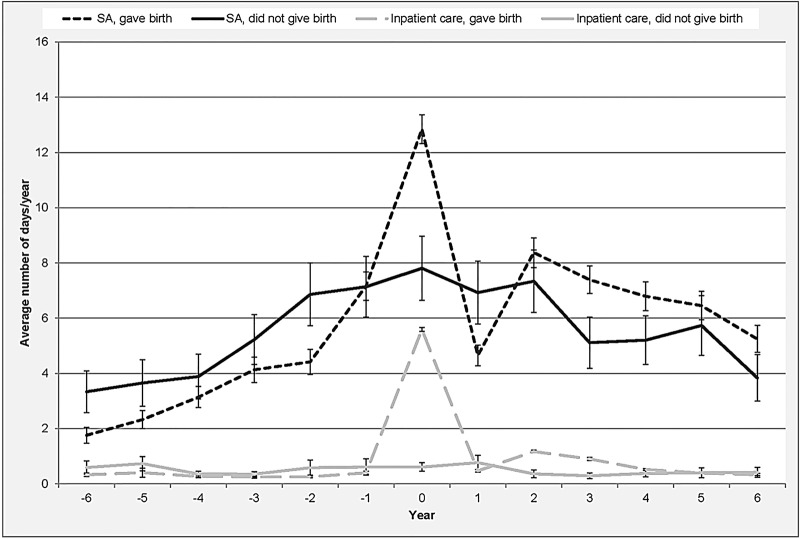

The average annual number of days with inpatient care and SA, respectively, is presented in figure 2. Up to year T0, women who did not give birth had a higher average number of hospitalisation days and SA days compared with those who gave birth. Women who gave birth had approximately 0.3 hospitalisation days per year, whereas those who did not give birth had around 0.5 hospitalisation days per year. The average number of SA days for women giving birth was 3.8 days/year and for those not giving birth 5.0 days/year. SA differences between those giving birth and those not giving birth were statistically significant with the exception of year (−4) and (−3). For inpatient care, the differences between those giving birth and those not giving birth were not statistically significant. The average number of inpatient days increased rapidly during T0 for women who gave birth, especially because of hospitalisation due to pregnancy and childbirth. After T0, the number of SA days decreased quickly among these women. For women who gave birth, days with inpatient care and SA in the years following T0 were to a large extent associated with subsequent childbirths.

Figure 2.

Average annual number of days on sickness absence (SA) and hospitalisation, respectively (with 95% CI), 6 years prior through 6 year after T0 for women who gave birth/did not give birth (n=5118).

Table 2 presents HR for the association between childbirth and hospitalisation for all diagnoses and for diagnoses where those related to pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period were excluded. When these diagnoses were removed, women who did not give birth and who had been hospitalised at least once before T0 had twice the risk of future hospitalisation compared with those not hospitalised prior to T0 (HR=2.3; 95% CI 1.6 to 3.3) after adjustments for birth year, delivery year and educational level. The association was explained by familial factors in the analysis of discordant twin pairs (HR 1.2; 0.8 to 1.9).

Table 2.

Cox proportional HR with 95% CI for the association between childbirth, hospitalisation before T0, and subsequent hospitalisation (ie, during year 3–5 after T0) in twins where at least one in the pair had her first childbirth during 1994–2009 and none before 1994, both including and excluding hospitalisation related to pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium

| Status childbirth and hospitalisation | All diagnoses |

Diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium excluded* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model a† | Model b‡ | Discordant twin pairs§,‡ | Model a† | Model b‡ | Discordant twin pairs¶,‡ | |

| All women (n=5118) | ||||||

| No childbirth, no hospitalisation before T0** | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) |

| No childbirth, hospitalisation before T0** | 2.5 (1.7 to 3.6) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.3) | 2.4 (1.3 to 4.5) | 2.7 (1.8 to 3.9) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.4) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Childbirth, no hospitalisation before T0** | 6.1(5.0 to 7.5) | 5.5 (4.5 to 6.8) | 8.3 (5.8 to 11.8) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Childbirth, hospitalisation before T0** | 6.5 (5.2 to 8.1) | 5.6 (4.4 to 7.1) | 7.9 (5.4 to 11.5) | 1.9 (1.4 to 2.5) | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.2) |

| Model a† | Model b‡ | Discordant twin pairs††,‡ | Model a† | Model b‡ | Discordant twin pairs‡‡,‡ | |

| Women who had at least one childbirth (n=2792) | ||||||

| No hospitalisation before T0** | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) | 1 (REF) |

| Hospitalisation before T0** | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.2) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.3) | 1.5 (1.2 to 2.0) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) |

Two models for adjustments as well as for discordant twin pairs.

*Diagnoses O00-O99.

†Adjusted for birth year.

‡Model a, and additional adjustments for delivery year and educational level.

§Twin pairs where one had a hospitalisation during the follow-up and the other did not (n=1016 pairs).

¶Twin pairs where one had a hospitalisation during the follow-up and the other did not (n=456 pairs).

**During the period 1–5 years prior to T0.

††Twin pairs (both giving birth) where one had a hospitalisation during the follow-up and the other did not (n=508 pairs).

‡‡Twin pairs (both giving birth) where one had a hospitalisation during the follow-up and the other did not (n=271 pairs).

When restricting the analyses to women who gave birth, a total of 2792 women were studied, that is, 1396 complete pairs in which both twins had given birth. The reference group constituted of mothers who had not been hospitalised prior to their first childbirth. Mothers who had been hospitalised before their first childbirth had a slightly higher HR for future hospitalisation when diagnoses related to pregnancy and childbirth were excluded (HR 1.5; 1.2 to 2.0). This association disappeared in the analyses of discordant twin pairs, suggesting an influence of familial factors (HR 1.0; 0.8 to 1.3).

Regardless of childbirth status, hospitalisation year 1–2 after T0 was a predictor of having a new SA in year 3–5 after T0 (table 3). Compared with women who did not give birth and who were not hospitalised in the first 2 years after T0, mothers hospitalised after their first childbirth had an HR of 2.4 (2.0–2.9) for a new SA after adjustments for birth year, delivery year and educational level. Hospitalisation after T0 was also associated with a new long-term SA (>90 days) in year 3–5 after T0 (table 3). Women who did not give birth had a nearly threefold risk of a new long-term SA in year 3–5 after T0 (HR 2.8; 1.5 to 5.1), whereas women who gave birth had an HR of 1.8 (1.3 to 2.5). The analyses of twin pairs discordant for having a new long-term SA in year 3–5 after T0 showed attenuated point estimates, hence suggesting that familial effects may play a role.

Table 4 presents results from the analyses in which we considered hospitalization before and after first childbirth as exposure, and new SA year 3–5 after T0 as outcome. Mothers who had been hospitalised at least once both before and after their first childbirth had a higher risk of future SA (HR 1.8; 1.4 to 2.2). These women also had a higher risk of long-term SA; however, these risk estimates were not statistically significant. After controlling for familial confounding, the estimated risk for long-term SA for those who had been hospitalised before T0 was in the same direction but the HR was reduced, which suggests that familial factors may also have an influence on the studied association.

Discussion

In this register study of a population-based Swedish cohort of female twins born between 1959 and 1990, the associations of delivery with hospitalisation and SA were examined, as well as whether familial (ie, genetic and shared, mainly childhood, environmental) factors were contributing to these associations. Just before the first childbirth, the SA days increased much for mothers, an increase that gradually decreased during the years after the delivery. We found hospitalisation prior to T0 to be a risk factor for future hospitalisation, regardless of childbirth status, as well as when excluding hospitalisation due to childbirth. Furthermore, hospitalisation after the first childbirth was associated with a higher HR of both short-term and long-term future SA. An additional analysis focusing solely on the women who gave birth showed that hospitalisation both before and after the first childbirth was associated with a higher risk of future SA. Familial factors seemed to have an influence on the association between hospitalisation and long-term SA, regardless of childbirth status.

In line with some previous studies,10 20 50 51 we found that SA increased in women during the time before the first childbirth. Giving birth was also associated with a future somewhat higher risk for SA, in line with that of those not giving birth. However, this higher risk could be due to subsequent pregnancies. A recent Norwegian study found that the increased SA risk in women in the years after pregnancy disappeared when SA during subsequent pregnancies were accounted for.20 Several explanations have been suggested for such higher levels of SA, among others the double burden hypothesis.20 52–54 This hypothesis has been questioned, as research has indeed shown that women who occupy multiple roles tend to be healthier than those who enact fewer roles.55–57 Thus, on the contrary, the combination of employment and parenthood does not seem to imply worse health. In our study, the annual rates of SA decreased steadily after the first childbirth, speaking in favour of this hypothesis. Further studies of this are warranted.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine long-term associations between childbirth, hospitalisation and both short-term and long-term SA. Women who gave birth did not have a higher risk for long-term SA or for hospitalisation (besides hospitalisation due to subsequent pregnancy and childbirth) when compared with women who did not give birth.

Those who did not give birth had a more stable pattern of SA during the studied period, however, with a slight increase in annual SA days over the years. This is in line with a Swedish study that examined whether family obligations influence the risk of SA in publicly employed women and found a slight risk increase for SA among women without children.58 Further, a broad systematic literature review published in 2004 provided no evidence of an association between having children in the household and an increased risk of SA.59 It is important to consider family situation when examining the association between having children and morbidity, as single women with children have been shown to have worse health30 31 60 and higher levels of SA.6 58

Even though pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period may increase the risk for disease and injury,25 27 our findings do not suggest that women who gave birth are more likely to be hospitalised after their first childbirth, except for hospitalisations related to subsequent deliveries. We found no differences in risk for future hospitalisation when comparing those who gave birth with those who did not. Thus, giving birth does not have to be associated with subsequent health problems. The fact that we found no differences in future hospitalisation between those who gave birth and those who did not may have different explanations. As mentioned above, one could expect that there is a health selection, where women who do not give birth may have worse health and choose not to have or cannot have a child. Also, giving birth is in itself a risk factor for future morbidity.16 19 22 Further, during the past decades, the number of women who voluntarily do not want to become parents has increased worldwide.61

Hospitalisation prior to the first childbirth or equivalent (T0) was a risk factor for future SA for all women, regardless of childbirth status. In particular, women who had been hospitalised both before and after T0 were at risk for future SA. Furthermore, we found an association between hospitalisation and future long-term SA.

When comparing women who gave birth with those who did not, with respect to exposure to hospitalisation and risk of SA, mothers hospitalised at least once after the first childbirth had a slightly higher risk for future SA regardless of duration, whereas those who did not give birth but were hospitalised after T0 had a higher risk for long-term SA.

Hospitalisation both before and after the year T0 seems to be the strongest indicator, that is, these individuals had the highest risk for future SA. Consequently, the women who had been hospitalised both before and after T0 had the highest risk for future SA. Our analyses of women who gave birth revealed a graded association between hospitalisation and SA, where those who only were hospitalised before or after their first childbirth had a higher risk of SA, whereas those who were hospitalised both before and after the first childbirth had even higher risks. Thus, we found a strong association between morbidity and future SA among women who gave birth—an association that often has been questioned regarding women with children.

Familial factors seemed to contribute to the association between hospitalisation before and after T0 among those who did not give birth. The influence of familial factors may relate to morbidity among women not giving birth—morbidity that might be more severe and potentially also being relatively strongly influenced by genetics. Familial factors also played a role in the associations between hospitalisation and future long-term SA. This could be related to the fact that the hospitalisation usually is required for severe conditions that may have a strong genetic component. However, since genetics has been shown to influence the risk of disability pension (DP)62 and some indications exist that genetics also plays a role in long-term SA and mortality, it can be suspected that the effects of familial factors on SA can be either direct or through other influential factors.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the population-based prospective cohort study design, including all in the study population, not a sample, using nationwide registers with high completeness and validity.43–45 Further, we used a large study cohort without loss to follow-up. With a twin study design, we were able to take familial influences into account. When measuring both exposure and outcome with register-based data, we avoid problem with recall bias.

This study, however, has some limitations. First of all, we do not know whether the women who did not give birth were childless voluntarily or not. Differences in health between voluntary and involuntary childlessness have been shown, where voluntarily childless women showed higher levels of overall well-being61 63 which might be related to hospitalisation and/or SA. Using inpatient care as a measure of morbidity has both its strengths and limitations. One limitation is that we thus selected more severe types of morbidity, and hence that does not include morbidity treated in outpatient care. Also, having had other types of morbidity data might have given another picture, and hopefully future studies will have such information. Another limitation is that the terms for inpatient care have changed during the studied period. In Sweden, inpatient care has over the years, to a great extent, been replaced by outpatient treatment. Therefore, some of the decrease in hospitalisation over the years is a result of a shift in the responsibility for inpatient care from hospitals to outpatient care facilities64; however, this affected all women equally, and is to some extent handled by adjusting for birth year. The CIs are wider in the years far from T0, for example, T6, due to fewer follow-up years for some—for example, for those who gave birth late during the studied period. Also, we lack information on the shorter SA spells among those employed. Further, the STR contains all twin births in Sweden; hence, immigrants are not included in this study, and as a consequence the external validity might be lower for women born outside Sweden.

It is important to be aware that giving birth is in focus here, irrespective of whether the child survived or not. Some of the women who did not give birth might be mothers, for example, due to adoption. Other studies in this area have ‘being mother’ or ‘living with child’ as an exposure term, rather than ‘giving birth’.

Conclusion

Women giving birth did not have a higher future SA risk than those not giving birth and results indicate a positive health selection into giving birth. Mothers with different types of morbidity, in terms of hospitalisation before and/or after giving birth, had higher risks for future SA. Most women had no SA in the 6 years following childbirth and those who had SA generally had that for shorter periods. Among the few women who had severe morbidity, in terms of hospitalisation, the future risk for SA was, as expected, higher. Hospitalisation prior to T0 was strongly associated with later hospitalisation and later SA. The high levels of inpatient care in women who did not give birth suggest that there is a health selection in giving birth, where the women who give birth have better health initially. However, most women had no hospitalisation and no SA.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KA and PS originated the idea. EB analysed the data in consultation with KA, LK, JN, AR and PS. EB wrote the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript, with important intellectual input from all the coauthors. All authors contributed in designing the study and to the interpretation of the results and to the writing and approval of the final article.

Funding: This study was financially supported by the Karolinska Institutet Strategic Research Program in Epidemiology (Dnr 7340/2012), the Swedish Society of Medicine (Dnr SLS-250931 and SLS-171611), the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (S2012/7938/SF), and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (2007-1762). The Swedish Twin Registry is supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Ministry for Higher Education, and AstraZeneca.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm, Sweden (2007/524-31).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Parrukoski S, Lammi-Taskula J. Parental leave policies and the economic crisis in the Nordin countries. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svedberg P, Ropponen A, Alexanderson K et al. Genetic susceptibility to sickness absence is similar among women and men: findings from a Swedish twin cohort. Twin Res Hum Genet 2012;15:642–8. 10.1017/thg.2012.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ugreninov E. Can family policy reduce mothers’ sick leave absence? A causal analysis of the Norwegian paternity leave reform. J Fam Econ Issues 2012;34:435–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 1. Aim, background, key concepts, regulations, and current statistics. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;32(Supplement 63):12–30. 10.1080/14034950410021808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexanderson K. Measuring health. Indicators for working women. In: Kilbom Å, Messing K, Bildt Thorbjörnsson C, eds. Women's health at work. Stockholm: National Institute for Working Life, 1998:121–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mastekaasa A. Parenthood, gender and sickness absence. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1827–42. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00420-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messing K, Östlin P. Gender equality, work and health: a review of the evidence. In: WHO , ed. Montreal, Stockholm: GWH, FCH, PHE, SDE, 2006:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen G, Östlin P, eds. Gender equity in health. The shifting frontiers of evidence and action. New York: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Härenstam A, Lindberg G. Gender inequalities in health: a Swedish perspective. Östlin P, Danielsson M, Diderichsen F, et al, eds. Harvard University Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexanderson K, Hensing G, Carstensen J et al. Pregnancy-related sickness absence among employed women in a Swedish county. Scand J Work Environ Health 1995;21:191–8. 10.5271/sjweh.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexanderson K, Hensing G, Leijon M et al. Pregnancy-related sickness absence in a Swedish County in 1985, 1986 and 1987. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:464–70. 10.1136/jech.48.5.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E. Gender differences in sickness absence and the gender division of family responsibilities. Uppsala: Institute for Evaluation of Labour market and Education Policy (IFAU), 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vistnes JP. Gender differences in days lost from work due to illness. Ind Labor Relat Rev 1997;50:304–23. 10.2307/2525088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sydsjo A, Sydsjo G, Kjessler B. Sick leave and social benefits during pregnancy—a Swedish-Norwegian comparison. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:748–54. 10.3109/00016349709024341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexanderson K, Sydsjo A, Hensing G et al. Impact of pregnancy on gender differences in sickness absence. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekeus C, Nilsson E, Gottvall K. Increasing incidence of anal sphincter tears among primiparas in Sweden: a population-based register study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008;87:564–73. 10.1080/00016340802030629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schytt E, Lindmark G, Waldenstrom U. Physical symptoms after childbirth: prevalence and associations with self-rated health. BJOG 2005;112:210–17. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazener CM, Abdalla M, Stroud P et al. Postnatal maternal morbidity: extent, causes, prevention and treatment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:282–7. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09132.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Lelong N et al. Women's health after childbirth: a longitudinal study in France and Italy. BJOG 2000;107:1202–9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rieck K, Telle K. Sick leave before, during and after pregnancy. Acta Sociologica 2013;56:117–37. 10.1177/0001699312468805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schytt E. Women's health after childbirth [Doctoral]. Karolinska Institutet, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schytt E, Hildingsson I. Physical and emotional self-rated health among Swedish women and men during pregnancy and the first year of parenthood. Sex Reprod Healthc 2011;2:57–64. 10.1016/j.srhc.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckmann CRB, Ling FW, Barzansky BM et al. Obstetrics and gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacker NF, Gambone JC, Hobel CJ. Essentials of obstetrics and gynecology: Saunders Elsevier, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaaja RJ, Greer IA. Manifestations of chronic disease during pregnancy. JAMA 2005;294:2751–7. 10.1001/jama.294.21.2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubertsson C, Wickberg B, Gustavsson P et al. Depressive symptoms in early pregnancy, two months and one year postpartum-prevalence and psychosocial risk factors in a national Swedish sample. Arch Womens Ment Health 2005;8:97–104. 10.1007/s00737-005-0078-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C, Li Q. Integrative review of research on general health status and prevalence of common physical health conditions of women after childbirth. Womens Health Issues 2008;18:267–80. 10.1016/j.whi.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milgrom J, Gemmill A, Bilszta J et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord 2008;108:147–57. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G et al. Work status, work hours and health in women with and without children. Occup Environ Med 2009;66:704–10. 10.1136/oem.2008.044883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burstrom B, Diderichsen F, Shouls S et al. Lone mothers in Sweden: trends in health and socioeconomic circumstances, 1979–1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:750–6. 10.1136/jech.53.12.750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burstrom B, Whitehead M, Clayton S et al. Health inequalities between lone and couple mothers and policy under different welfare regimes—the example of Italy, Sweden and Britain. Soc Sci Med 2010;70:912–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 3. Causes of sickness absence: research approaches and explanatory models. Scand J Public Health 2004;32(Suppl 63):36–43. 10.1080/14034950410021835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Englund L, Tibblin G, Svärsudd K. Variations in sick-listing practice among male and female physicians of different specialities based on case vignettes. Scand J Prim Health Care 2000;1:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plomin R, DeFries J, McClean GE et al. Behavioral genetics. New York: Worth Publishers, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plomin R, Owen MJ, McGuffin P. The genetic basis of complex human behaviors. Science 1994;264:1733–9. 10.1126/science.8209254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bienvenu OJ, Davydow DS, Kendler KS. Psychiatric ‘diseases’ versus behavioral disorders and degree of genetic influence. Psychol Med 2011;41:33–40. 10.1017/S003329171000084X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Battie MC, Videman T, Levalahti E et al. Heritability of low back pain and the role of disc degeneration. Pain 2007;131:272–80. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacGregor AJ, Snieder H, Rigby AS et al. Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Modifiable risk factors as predictors of all-cause mortality: the roles of genetics and childhood environment. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:985–93. 10.1093/aje/kwf151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lichtenstein P, De Faire U, Floderus B et al. The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J Int Med 2002;252:184–205. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL et al. The STAGE cohort: a prospective study of tobacco use among Swedish twins. Nicotine Tob Res 2008;10:1727–35. 10.1080/14622200802443551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Board of Health and Welfare. Causes of death 2010. Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cnattingius S, Ericson A, Gunnarskog J et al. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Soc Med 1990;18:143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hensing G, Alexanderson K, Allebeck P et al. How to measure sickness absence? Literature review and suggestion of five basic measures. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heck KE, Schoendorf KC, Ventura SJ et al. Delayed childbearing by education level in the United States, 1969–1994. Matern Child Health J 1997;1:81–8. 10.1023/A:1026218322723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mills M, Rindfuss RR, McDonald P et al. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod Update 2011;17:848–60. 10.1093/humupd/dmr026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bratberg E, Naz G. Does paternity leave affect mothers’ sickness absence? Working papers in Economics University of Bergen, 2009.

- 51.Sydsjo A, Sydsjo G, Alexanderson K. Influence of pregnancy-related diagnoses on sick-leave data in women aged 16–44. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001;10:707–14. 10.1089/15246090152563597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blank N, Diderichsen F. Short-term and long-term sick-leave in Sweden: relationships with social circumstances, working conditions and gender. Scand J Soc Med 1995;23:265–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lidwall U, Marklund S, Voss M. Work-family interference and long-term sickness absence: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:676–81. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vaananen A, Kevin MV, Ala-Mursula L et al. The double burden of and negative spillover between paid and domestic work: associations with health among men and women. Women Health 2004;40:1–18. 10.1300/J013v40n03_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fokkema T. Combining a job and children: contrasting the health of married and divorced women in the Netherlands? Soc Sci Med 2002;54:741–52. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00106-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lahelma E, Arber S, Kivela K et al. Multiple roles and health among British and Finnish women: the influence of socioeconomic circumstances. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:727–40. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McMunn A, Bartley M, Hardy R et al. Life course social roles and women's health in mid-life: causation or selection? J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:484–9. 10.1136/jech.2005.042473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voss M, Josephson M, Stark S et al. The influence of household work and of having children on sickness absence among publicly employed women in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:564–72. 10.1177/1403494807088459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave—general studies. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:49–108. 10.1080/14034950410021853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weitoft GR, Haglund B, Hjern A et al. Mortality, severe morbidity and injury among long-term lone mothers in Sweden. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:573–80. 10.1093/ije/31.3.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agrillo C, Nelini C. Childfree by choice: a review. J Cult Geography 2008;25:347–63. 10.1080/08873630802476292 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Narusyte J, Ropponen A, Silventoinen K et al. Genetic liability to disability pension in women and men: a prospective population-based twin study. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e23143 10.1371/journal.pone.0023143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeffries S, Konnert C. Regret and psychological well-being among voluntarily and involuntarily childless women and mothers. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2002;54:89–106. 10.2190/J08N-VBVG-6PXM-0TTN [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silfverhielm H, Kamis-Gould E. The Swedish mental health system. Past, present, and future. Int J Law Psychiatryz 2000;23:293–307. 10.1016/S0160-2527(00)00039-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.