Abstract

Objective

To investigate whether common infection foci (pulmonary, intra-abdominal and primary bacteraemia) are associated with variations in mortality risk in patients with sepsis.

Design

Prospective, observational cohort study.

Setting

Three surgical intensive care units (ICUs) at a university medical centre.

Participants

A total of 327 adult Caucasian patients with sepsis originating from pulmonary, intra-abdominal and primary bacteraemia participated in this study.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The patients were followed for 90 days and mortality risk was recorded as the primary outcome variable. To monitor organ failure, sepsis-related organ failure assessment (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SOFA) scores were evaluated at the onset of sepsis and throughout the observational period as secondary outcome variables.

Results

A total of 327 critically ill patients with sepsis were enrolled in this study. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the 90-day mortality risk was significantly higher among patients with primary bacteraemia than among those with pulmonary and intra-abdominal foci (58%, 35% and 32%, respectively; p=0.0208). To exclude the effects of several baseline variables, we performed multivariate Cox regression analysis. Primary bacteraemia remained a significant covariate for mortality in the multivariate analysis (HR 2.10; 95% CI 1.14 to 3.86; p=0.0166). During their stay in the ICU, the patients with primary bacteraemia presented significantly higher SOFA scores than those of the patients with pulmonary and intra-abdominal infection foci (8.5±4.7, 7.3±3.4 and 5.8±3.5, respectively). Patients with primary bacteraemia presented higher SOFA-renal score compared with the patients with other infection foci (1.6±1.4, 0.8±1.1 and 0.7±1.0, respectively); the patients with primary bacteraemia required significantly more renal replacement therapy than the patients in the other groups (29%, 11% and 12%, respectively).

Conclusions

These results indicate that patients with sepsis with primary bacteraemia present a higher mortality risk compared with patients with sepsis of pulmonary or intra-abdominal origins. These results should be assessed in patients with sepsis in larger, independent cohorts.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to evaluate mortality risk among patients with sepsis with primary bloodstream infections compared with those with respiratory or intra-abdominal infections over an observational period of 90 days.

The strengths of our study include that it is the first to investigate organ-specific manifestations associated with common sepsis infection sites (respiratory, intra-abdominal and bloodstream) by quantifying Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores and evaluating the requirements for organ support in the intensive care unit.

One potentially uncontrolled confounder that was not adjusted for is appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Introduction

Sepsis is defined as a systemic inflammatory response that occurs during severe infection.1–3 Sepsis affects more than 750 000 patients in the USA each year and remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide.4 Although the incidence of this major healthcare problem has been increasing, the implementation of early goal-directed therapy in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock has in part successfully reduced mortality.5 Guidelines for disease control have been written by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC), a joint collaboration between the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine committed to reducing mortality from severe sepsis and septic shock worldwide.6 These guidelines contain clear recommendations for improving disease outcomes (eg, guidelines for resuscitation and recommendations pertaining to infections, including the use of diagnostics, haemodynamic support and adjunctive therapy, and supportive therapy for severe sepsis).6

Respiratory, intra-abdominal, urinary and primary bloodstream infections (BSIs) make up 80% of all infection sites.7 According to epidemiological data, the lung is the most common site of infection, followed by the abdomen and the blood.2

Pneumonia, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) and subsequent sepsis remain important causes of morbidity and mortality in critically ill patients despite advances in antimicrobial therapy, better supportive care modalities and a wide range of preventive measures.8–10

Intra-abdominal infections are a common cause of sepsis. These infections comprise a markedly heterogeneous group of infectious processes that share an anatomical site of origin between the diaphragm and the pelvis.11 Their clinical course is dictated by a number of infection-related factors, including the microbiology of the infection, the anatomical location, the degree of localisation and the presence of correctable anatomical derangements involving intra-abdominal viscera.12 13

BSIs are a major cause of death due to nosocomial events in intensive care units (ICUs).14 Immunosuppression and invasive healthcare procedures act together to create a high risk of nosocomial BSIs in critically ill patients.15 The outcomes of BSIs have been the focus of many case–control and cohort studies.15–17 BSIs lead to poor patient outcomes,16 18 prolonged patient stays in the ICU and in the hospital,16 19 20 and substantial extra medical costs.21 22

Whether the characteristics of the infection, infection site and pathogenic organism independently affect the outcome in patients with sepsis remains a subject of debate. Whereas previous studies have shown an independent, significant contribution of the infection site and the pathogenic organism to the survival of patients with sepsis,23 recent investigations have not found any significant impact of the infection site on mortality among patients with sepsis.24

This study aimed to explore whether common origins of sepsis infections, particularly the respiratory, intra-abdominal and BSI sites, are associated with changes in the 90-day survival rate among patients with sepsis in a representative university medical centre, where patients are treated according to the most recent sepsis guidelines.

Materials and methods

Patients

Adult Caucasian patients admitted to ICUs at the University Medical Center-Goettingen (UMG) between April 2012 and May 2013 were screened daily according to the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine (ACCP/SCCM) criteria for sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock.25 26 For each patient, written and informed consent was obtained from either the patient or their legal representative. Patients were enrolled if they presented sepsis of a respiratory, intra-abdominal or primary bloodstream origin. Since inter-racial genetic differences may affect the clinical course of infectious diseases, we have exclusively recruited Caucasians, who form the majority of patients admitted to our surgical ICUs, into this clinical investigation. Caucasian origin was assessed by questioning the patients, their next of kin or their legal representatives.

Definitions

In this study, patients with sepsis of respiratory origin had HAP or VAP. HAP is the most frequent infection in surgical ICUs and is defined as a pulmonary infection that was not incubating at the time of admission and that occurred at least 48 h after hospital admission.27 VAP is defined as either a pulmonary infection arising more than 48 h after tracheal intubation with no evidence of pneumonia at the time of intubation or the diagnosis of a new pulmonary infection if the initial ICU admission was due to pneumonia.27

Typically, patients with intra-abdominal infections in the surgical ICU develop secondary peritonitis as a result of microbial infection of the peritoneal space following perforation, abscess formation, ischaemic necrosis or a penetrating injury of the intra-abdominal contents.11

Primary BSI comprises BSI of unknown origin in patients without an identifiable focus for the infection and intravascular catheter-related BSI (catheter, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator or pacemaker related) according to the International Sepsis Forum Consensus Conference on Definitions of Infection in the Intensive Care Unit.11

Exclusion criteria

As described previously,28 29 the patient exclusion criteria were the following: (1) age less than 18 years; (2) being pregnant or nursing an infant; (3) immunosuppressive therapy (eg, cyclosporine or azathioprine) or cancer-related chemotherapy; (4) documented or suspected acute myocardial infarction within the previous 6 weeks; (5) a history of New York Heart Association functional class IV chronic heart failure; (6) HIV infection; (7) a do not resuscitate or do not treat order or the patient and/or his or her legal representative not being committed to aggressive management; (8) not being expected to survive the 28-day observation period or not being likely to be placed on life support because of an uncorrectable medical condition, including a poorly controlled neoplasm or end-stage lung disease; (9) a chronic vegetative state or a similar long-term neurological condition; (10) current participation in any interventional study (of a drug or device); (11) inability to be fully evaluated during the study period and (12) being a study-site employee or a family member of a study-site employee involved in conducting this study.

Data collection

Patients were followed up for 90 days and mortality risk was recorded as the primary outcome variable. Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA),30 and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II31 scores were evaluated at the onset of sepsis. Organ function was reassessed over 28 days in the ICU to monitor morbidity as previously described.28 Organ failure, organ support requirements and the length of ICU stay were recorded as secondary outcome variables. All relevant clinical data were extracted from the electronic patient record system (IntelliSpace Critical Care and Anesthesia (ICCA); Philips Healthcare, Andover, Massachusetts, USA); all medical records, including microbiology reports, can be found in this system. We sought to determine whether patients suffered from pre-existing conditions, for example, comorbidities by examining physicians’ notes, administering an anamnestic questionnaire to the patients or their legal representatives and consulting each patient's family doctor.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software (V.10; StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA). Based on contingency tables, significance was calculated using two-sided Fisher's exact test or χ2 test, as appropriate. Two continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Time-to-event data were compared using the log-rank test from the Statistica package for Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. For variables identified as significant in univariate survival analyses (respiratory infections, intra-abdominal infections and primary bacteraemia) and the potential confounders (age, gender and body mass index (BMI)) and covariates that varied at baseline (diabetes mellitus (insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, IDDM), history of cancer and ‘No history of surgery’), we performed multivariate Cox regression analysis to examine survival times. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 327 adult Caucasian patients with sepsis were enrolled in this study. At enrolment, 61% of the patients had a pulmonary infection; 32% suffered from an intra-abdominal infection and 7% presented with a primary BSI (table 1). Patients’ ages ranged from 19 to 91 years (median, 65 years). At baseline, patients’ SOFA and APACHE II scores, which measure disease severity, were 9.3±4.0 and 21.5±7.3, respectively (table 1). Comorbidities included hypertension, myocardial infarction history, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal dysfunction, non-IDDM, IDDM, chronic liver diseases, history of cancer and a history of stroke (table 1). Many patients were discharged before 90 days. We were able to follow all of these patients. If the patient or legal representative could not be reached by telephone or mail, we confidentially contacted the local registry office and inquired whether the patient was still alive (still registered).

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics with regard to the infection site

| All n=327 |

Pulmonary n=198 |

Intra-abdominal n=105 |

Bloodstream n=24 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 62±15 | 61±15 | 65±13 | 60±16 | 0.2426 |

| Male (%) | 67% | 70 | 61 | 62 | 0.2614 |

| Body mass index (mean±SD) | 27±6 | 27±7 | 27±5 | 29±5 | 0.0885 |

| SOFA score (mean±SD) | 9.3±4.0 | 9.4±3.6 | 8.9±4.7 | 10.5±5.1 | 0.3099 |

| APACHE II score (mean±SD) | 21.5±7.3 | 21.8±6.8 | 20.6±8.1 | 22.8±7.6 | 0.3538 |

| Organ support (%) | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 85 | 90 | 74 | 87 | 0.0008 |

| Use of vasopressor | 64 | 62 | 65 | 70 | 0.6778 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 8 | 7 | 9 | 20 | 0.0781 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 57 | 55 | 59 | 66 | 0.5395 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 0.9087 |

| COPD | 17 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 0.9880 |

| Renal dysfunction | 11 | 10 | 9 | 25 | 0.0857 |

| Diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 0.8928 |

| Diabetes mellitus (IDDM) | 11 | 8 | 11 | 33 | 0.0015 |

| Chronic liver diseases | 5 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 0.1538 |

| History of cancer | 18 | 15 | 30 | 0 | 0.0003 |

| History of stroke | 6 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0.2192 |

| Recent surgical history (%) | |||||

| Elective surgery | 30 | 27 | 37 | 25 | 0.1730 |

| Emergency surgery | 48 | 45 | 56 | 42 | 0.1401 |

| No history of surgery | 21 | 28 | 7 | 33 | <0.0001 |

The data are presented as the means±SDs or percentages.

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; NIDDM, non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Disease severity at the onset of sepsis

No differences in age, gender, or BMI were found among the three groups of study participants. Moreover, no differences were found in the SOFA and APACHE II scores with respect to the infection sites at the onset of sepsis. The patients in the group with intra-abdominal infections required significantly less mechanical ventilation compared with the other groups with pulmonary and BSIs (74%, 90% and 87%, respectively). The patients with BSIs suffered significantly more from IDDM compared with patients with pulmonary or intra-abdominal infections (33%, 8% and 11%, respectively). In contrast, none of the patients with BSIs had a history of cancer, unlike the patients with pulmonary and intra-abdominal infections (15% and 30%, respectively; table 1).

Mortality analysis

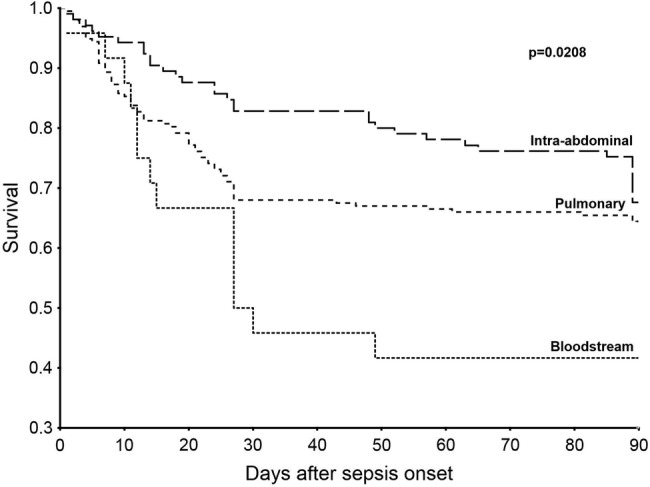

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the 90-day mortality risk was significantly higher among patients with primary bacteraemia than among those with pulmonary and intra-abdominal foci (58%, 35% and 32%, respectively; figure 1). Analysis of the 28-day mortality data similarly revealed that the patients with BSIs had a significantly increased risk of death compared with the patients with pulmonary and intra-abdominal infections (50%, 32% and 17%, respectively; table 2). Moreover, 90-day mortality analysis suggested a higher incidence of death among the patients with BSIs, although this finding was not significant (p=0.0544; table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. The Kaplan-Meier curve shows the survival curves until day 90 for the three infection site groups. The mortality risk among the patients under study was higher among the patients with bloodstream infections compared with those in the pulmonary and intra-abdominal infection groups (p=0.0208, log-rank test).

Table 2.

Disease severity with regard to infection site

| All n=327 |

Pulmonary n=198 |

Intra-abdominal n=105 |

Bloodstream n=24 |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOFA | 6.9±3.6 | 7.3±3.4 | 5.8±3.5 | 8.5±4.7 | 0.0002 |

| SOFA subscores | |||||

| SOFA-respiratory | 1.9±0.7 | 2.2±0.6 | 1.5±0.7 | 1.9±0.9 | <0.0001 |

| SOFA-cardiovascular | 1.5±0.9 | 1.5±0.9 | 1.3±0.9 | 1.7±1.2 | 0.4567 |

| SOFA-central nervous system | 1.8±1.1 | 2.1±1.0 | 1.4±1.0 | 2.0±1.2 | <0.0001 |

| SOFA-renal | 0.8±1.1 | 0.8±1.1 | 0.7±1.0 | 1.6±1.4 | 0.0028 |

| SOFA-coagulation | 0.3±0.5 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.2±0.5 | 0.6±0.8 | 0.4662 |

| SOFA-hepatic | 0.4±0.7 | 0.3±0.6 | 0.5±0.8 | 0.5±0.6 | 0.0030 |

| Organ support* (%) | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 85 | 62 | 76 | <0.0001 | |

| Use of vasopressor | 54 | 45 | 49 | 0.8355 | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 11 | 12 | 29 | 0.0069 | |

| Length of stay in ICU (days) | 18±15 | 17±14 | 20±16 | 16±13 | 0.5061 |

| Mortality analysis (%) | |||||

| Death by day 28 | 94 (28) | 64 (32) | 18 (17) | 12 (50) | 0.0012 |

| Death by day 90 | 118 (36) | 70 (35) | 34 (32) | 14 (58) | 0.0544 |

The data are presented as means±SDs or percentages.

*Based on the total number of observations during the follow-up period.

ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Multivariate analysis

To exclude the effects of several baseline variables on survival among the three groups being investigated, we performed multivariate Cox regression analysis. BSI remained a significant covariate for mortality in the multivariate analysis (HR 2.10; 95% CI 1.14 to 3.86; p=0.0166; table 3). This finding indicates that, despite baseline differences in some variables (ie, IDDM, cancer and ‘No history of surgery’), the presence of a primary BSI remains a prognostic variable with a significant effect on the outcome (90-day survival; table 3).

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis

| Infection site | Variable | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.03 | 0.0009 | |

| Gender | 1.19 | 0.80 to 1.76 | 0.3803 | |

| BMI | 1.00 | 0.97 to 1.03 | 0.7058 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (IDDM) | 1.29 | 0.75 to 2.19 | 0.3450 | |

| History of cancer | 1.26 | 0.81 to 1.95 | 0.2921 | |

| No history of surgery | 1.37 | 0.87 to 2.14 | 0.1634 | |

| Pulmonary infection | 1.05 | 0.72 to 1.55 | 0.7675 | |

| Intra-abdominal | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.03 | 0.0007 | |

| Gender | 1.17 | 0.79 to 1.73 | 0.4302 | |

| BMI | 1.00 | 0.97 to 1.03 | 0.6497 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (IDDM) | 1.28 | 0.75 to 2.16 | 0.3534 | |

| History of cancer | 1.33 | 0.85 to 2.06 | 0.2036 | |

| No history of surgery | 1.25 | 0.80 to 1.97 | 0.3209 | |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 0.71 | 0.46 to 1.08 | 0.1142 | |

| Bloodstream | ||||

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | 0.0007 | |

| Gender | 1.18 | 0.80 to 1.75 | 0.3956 | |

| BMI | 1.00 | 0.97 to 1.03 | 0.7930 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (IDDM) | 1.07 | 0.61 to 1.88 | 0.7877 | |

| History of cancer | 1.36 | 0.87 to 2.12 | 0.1719 | |

| No history of surgery | 1.30 | 0.84 to 2.02 | 0.2290 | |

| Bloodstream infection | 2.10 | 1.14 to 3.86 | 0.0166 | |

BMI, body mass index; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus.

Disease severity

During the observational period, patients with BSIs presented significantly higher mean SOFA scores compared with patients in the other groups (8.5±4.7, 7.3±3.4 and 5.8±3.5, respectively; table 2). Four of the six organ-specific SOFA scores (respiratory, central nervous system (CNS), renal and hepatic) varied significantly among the study groups. The patients with pulmonary infections presented higher SOFA-respiratory scores than did patients with intra-abdominal and BSIs (2.2±0.6, 1.5±0.7 and 1.9±0.9, respectively; table 2). The patients with pulmonary and BSIs required more mechanical ventilation than patients with intra-abdominal infections (85%, 76% and 62%, respectively; table 2). Patients with mechanical ventilation usually received lung-protective ventilation (tidal volume of 6–8 mL/kg predicted body weight) and were treated according to structured weaning protocols of the ICUs. Weaning protocols included daily trials of spontaneous breathing, gradual reduction in pressure support and use of non-invasive mechanical ventilation for extubated patients. The patients with pulmonary and BSIs presented higher SOFA-CNS scores than those of the patients with intra-abdominal infections (2.1±1.0, 2.0±1.2 and 1.4±1.0, respectively; table 2). Analysis of the SOFA-renal scores indicated that the patients with BSIs presented higher SOFA-renal scores over the study period in the ICU compared with the patients with pulmonary and intra-abdominal infections (1.6±1.4, 0.8±1.1 and 0.7±1.0, respectively; table 2). These patients also required significantly more renal replacement therapy (29%, 11% and 12%, respectively; table 2). The SOFA-hepatic score was significantly higher in the patients with intra-abdominal and BSIs compared with the patients with pulmonary infections (0.5±0.8, 0.5±0.6 and 0.3±0.6, respectively; table 2). Additional results regarding disease severity were added to the online supplementary data, table S1.

In addition, the Gram-negative infection rate was significantly higher among the patients with pulmonary infections (75%) compared with those whose sepsis had intra-abdominal and BSI origins (57% and 54%, respectively; table 4). Additional results regarding microbiological findings and anti-infective therapy were added to the online supplementary data, tables S2 and S3, respectively.

Table 4.

Infection types over the observational period

| Infection site | Pulmonary (%) | Intra-abdominal (%) | Bloodstream (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infection type | ||||

| Gram-negative bacteria | 75 | 57 | 54 | 0.0026 |

| Gram-positive bacteria | 78 | 84 | 79 | 0.5142 |

| Fungus | 52 | 76 | 42 | <0.0001 |

| Virus | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.4941 |

Furthermore, patients with sepsis with intra-abdominal infections presented a higher incidence of fungal infections (76%) compared with the patients with pulmonary and BSIs (52% and 42%, respectively; table 4). In this study, blood cultures and cultures of samples from other sites, such as urine, cerebrospinal fluid, surgical wounds, respiratory secretions or other body fluids that may be the source of infection, were taken at sepsis onset and over the observational period in the ICU in accordance with clinical judgement, as indicated. The bacteraemia findings were only cultural.

Sometimes, infection foci could not be microbiologically verified, especially if the patients were pretreated with antibiotics on normal wards before they were admitted to the ICU.

Discussion

The present study addressed whether common infection sites among patients with sepsis are associated with the survival rate.

The primary end point, the mortality risk within 90 days of the onset of sepsis, was higher in patients with primary BSIs compared with those with respiratory or intra-abdominal infections (58%, 35% and 32%, respectively; figure 1). Primary bacteraemia remained a significant covariate for mortality in the multivariate analysis (table 3).

According to the SOFA and APACHE II scores, the infection site was not associated with the acute illness severity at the onset of sepsis (table 1). We believe that the similarity in SOFA and APACHE II scores at sepsis onset among the three groups can be attributed to the phenotypic heterogeneity of sepsis. This heterogeneity is affected by several factors, including the causative organism of the infection and the amount of time that elapsed since the infection began, as well as by individual patient characteristics, such as comorbidities and genetic makeup.28

The most significant result of this study with respect to the 90-day mortality risk was that the mortality rate (58%) was higher among patients with primary BSIs; this result is in agreement with the results of several previous investigations that found similar mortality rates in patients with nosocomial BSIs; for example, Garrouste-Orgeas et al15 found that patients with nosocomial BSI had a mortality rate of 61.5%.14 Our study also goes beyond previous investigations by evaluating a longer term end point (90 days); this endpoint was investigated because patients with sepsis continue to face an increased risk of mortality even after ICU and hospital discharge.32

Severe morbidity, quantified by the SOFA mean score in patients with primary BSIs, resulted in an increased 28-day mortality rate compared with the patients with pulmonary and intra-abdominal infections (50%, 32% and 17%, respectively; table 2).

The strengths of our study include that it is the first to investigate organ-specific manifestations associated with common sepsis infection sites (respiratory, intra-abdominal and bloodstream) by quantifying SOFA scores and evaluating the requirements for organ support in the ICU (table 2). The more pronounced types of respiratory failure, which are quantified by the SOFA-respiratory score and the need for mechanical ventilation (table 2), among patients with pulmonary infections are plausible because these patients frequently present comprised pulmonary function. Patients with primary bacteraemia are also at a high risk of respiratory failure due to systemic inflammatory response syndrome, release of proinflammatory cytokines (such as tumour necrosis factor, interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-633), and recruitment of neutrophils to the lungs which induces the release of toxic mediators, such as reactive oxygen species and proteases, thus contributing to lung damage and respiratory failure.34

We believe that the difference in the SOFA-CNS score between the genotypes (with higher scores in the respiratory and the bloodstream groups) occurred because patients in these groups required much more mechanical ventilation causing them to be treated more frequently with sedating medication; this impacts the CNS and thus affects the SOFA-CNS score.

The observed distinct renal failure among patients with BSI indicated by the SOFA-renal score, which was accompanied by frequent renal replacement therapy (table 2), was in accordance with former observations indicating that BSIs are associated with a higher incidence of renal failure.35 The frequent utilisation of renal replacement therapy suggests persistent organ dysfunction, which is a well-known contributor to sepsis-related mortality and may explain the higher mortality among patients with BSI observed in our study (table 2 and figure 1).36

The SOFA-hepatic score was higher among patients with intra-abdominal and primary BSIs compared with patients with pulmonary infections (table 2). This result can be attributed to the fact that Kupffer cells release several cytokines able to induce hepatocellular dysfunction in response to endotoxaemia in patients with BSIs.37

There are some limitations to this study along with potential confounding. One limitation to this study is the possibility of selection bias; for example, the patients in this study may have had a higher mortality rate in general than patients with sepsis in other ICUs (eg, in secondary medical care centres) because patients admitted to our surgical ICUs frequently had more severe coexisting diseases than did patients in other ICUs (non-tertiary care centre ICUs). A second potential limitation to this study is measurement bias. For example, many clinical parameters (eg, blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory frequency) were registered automatically in the electronic patient record system, and we cannot guarantee that all registered clinical parameters were always correct because of potential measurement errors. However, we did check all clinical records for plausibility before conducting our statistical analysis. Finally, one uncontrolled confounder that was not adjusted for is appropriate antibiotic therapy. Although patients with clinical signs of infection were routinely promptly given antibiotic therapy, data regarding the exact times at which patients received antibiotic doses after sepsis onset are unavailable.

To the best of our knowledge, this investigation is the first to evaluate 90-day survival rates with respect to common sepsis infection sites (respiratory, intra-abdominal and primary bloodstream). This study revealed a significantly higher mortality rate among patients with primary BSIs (58%) compared with patients with respiratory and intra-abdominal infections, although all patients were treated according to current guidelines for the treatment of sepsis (Surviving Sepsis Campaign).6 Owing to this dramatically higher mortality rate among patients with primary bloodstream sepsis, we believe that future sepsis trials should focus on this vulnerable group of high-risk patients. More appropriate interventions and further improvements in prevention and care are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the ICUs of the Department of Anesthesiology and the Department of General and Visceral Surgery, all of whom were involved in patient care. The authors also thank Benjamin Liese, Simon Wilmers, Chang Ho Hong, Sebastian Gerber and Maximillian Steinau for their dedicated help with the data collection for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the study design, data acquisition (clinical and experimental), or the analysis and interpretation of data. Specifically, YK collected clinical data and participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the data. AFP, JE, MG and MB contributed to the study design, supervised patient enrolment and clinical data monitoring and interpreted data. TB contributed to the study design and conception and performed and approved the statistical analyses. AM and JH designed the study, supervised the sample and data collection, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved either in the writing or revising of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Funds of Göttingen University.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the University of Goettingen Ethics Committee in Goettingen, Germany (1/15/12) and conformed to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (Seoul, 2008).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 2009;302:2323–9. 10.1001/jama.2009.1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:344–53. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000194725.48928.3A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien JM Jr, Ali NA, Aberegg SK et al. Sepsis. Am J Med 2007;120:1012–22. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–10. 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1368–77. 10.1056/NEJMoa010307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580–637. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alberti C, Brun-Buisson C, Burchardi H et al. Epidemiology of sepsis and infection in ICU patients from an international multicentre cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2002;28:108–21. 10.1007/s00134-001-1143-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.No authors listed]. Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventive strategies. A consensus statement, American Thoracic Society, November 1995. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1711–25. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craven DE, Kunches LM, Kilinsky V et al. Risk factors for pneumonia and fatality in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;133:792–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niederman MS. Guidelines for the management of respiratory infection: why do we need them, how should they be developed, and can they be useful? Curr Opin Pulm Med 1996;2:161–5. 10.1097/00063198-199605000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calandra T, Cohen J; International Sepsis Forum Definition of Infection in the ICU Consensus Conference. The international sepsis forum consensus conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2005;33:1538–48. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000168253.91200.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans HL, Raymond DP, Pelletier SJ et al. Diagnosis of intra-abdominal infection in the critically ill patient. Curr Opin Crit Care 2001;7:117–21. 10.1097/00075198-200104000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall JC, Innes M. Intensive care unit management of intra-abdominal infection. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2228–37. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000087326.59341.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timsit JF, Laupland KB. Update on bloodstream infections in ICUs. Curr Opin Crit Care 2012;18:479–86. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e328356cefe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Tafflet M et al. ; OUTCOMEREA Study Group. Excess risk of death from intensive care unit-acquired nosocomial bloodstream infections: a reappraisal. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:1118–26. 10.1086/500318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pittet D, Tarara D, Wenzel RP. Nosocomial bloodstream infection in critically ill patients. Excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA 1994;271:1598–601. 10.1001/jama.1994.03510440058033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renaud B, Brun-Buisson C; ICU-Bacteremia Study Group. Outcomes of primary and catheter-related bacteremia. A cohort and case-control study in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1584–90. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.9912080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL Jr et al. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep 2007;122:160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Digiovine B, Chenoweth C, Watts C et al. The attributable mortality and costs of primary nosocomial bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:976–81. 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9808145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rello J, Ochagavia A, Sabanes E et al. Evaluation of outcome of intravenous catheter-related infections in critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1027–30. 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9911093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perencevich EN, Stone PW, Wright SB et al. Raising standards while watching the bottom line: making a business case for infection control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:1121–33. 10.1086/521852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin MY, Hota B, Khan YM et al. ; CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Quality of traditional surveillance for public reporting of nosocomial bloodstream infection rates. JAMA 2010;304:2035–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J, Cristofaro P, Carlet J et al. New method of classifying infections in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2004;32:1510–26. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000129973.13104.2D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zahar JR, Timsit JF, Garrouste-Orgeas M et al. Outcomes in severe sepsis and patients with septic shock: pathogen species and infection sites are not associated with mortality. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1886–95. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821b827c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB et al. ; ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest 2009;136(5 Suppl):e28 10.1378/chest.09-2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1250–6. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:388–416. 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansur A, von Gruben L, Popov AF et al. The regulatory toll-like receptor 4 genetic polymorphism rs11536889 is associated with renal, coagulation and hepatic organ failure in sepsis patients. J Transl Med 2014;12:177 10.1186/1479-5876-12-177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansur A, Hinz J, Hillebrecht B et al. Ninety-day survival rate of patients with sepsis relates to programmed cell death 1 genetic polymorphism rs11568821. J Investig Med 2014;62:638–43. 10.231/JIM.0000000000000059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vincent JL, de Mendonca A, Cantraine F et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 1998;26: 1793–800. 10.1097/00003246-199811000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985;13:818–29. 10.1097/00003246-198510000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khamsi R. Execution of sepsis trials needs an overhaul, experts say. Nat Med 2012;18:998–9. 10.1038/nm0712-998b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin TR. Lung cytokines and ARDS: Roger S. Mitchell Lecture. Chest 1999;116(1 Suppl):2S–8S. 10.1378/chest.116.suppl_1.2S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Windsor AC, Mullen PG, Fowler AA et al. Role of the neutrophil in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Br J Surg 1993;80:10–17. 10.1002/bjs.1800800106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shmuely H, Pitlik S, Drucker M et al. Prediction of mortality in patients with bacteremia: the importance of pre-existing renal insufficiency. Ren Fail 2000;22:99–108. 10.1081/JDI-100100856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent JL, Nelson DR, Williams MD. Is worsening multiple organ failure the cause of death in patients with severe sepsis? Crit Care Med 2011;39:1050–5. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eda29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koo DJ, Chaudry IH, Wang P. Kupffer cells are responsible for producing inflammatory cytokines and hepatocellular dysfunction during early sepsis. J Surg Res 1999;83:151–7. 10.1006/jsre.1999.5584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.