Abstract

Background

Although pentavalent antimony compounds are used as antileishmanial drugs but they are associated with limitations and several adverse complications. Therefore, always effort to find a new and effective treatment is desired. In this study, the effect of ZnO nanoparticles with mean particle size of 20 nanometers (nm) on Leishmania major promastigotes and amastigotes was evaluated.

Methods

Viability percentage of promastigotes after adding different concentrations of ZnO nanoparticles (30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml) to the parasite culture was evaluated by MTT assay. In the flow cytometry study, Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis detection Kit was used to study the induced apoptosis and necrotic effects.

Result

IC50 after 24 hours of incubation was 37.8 μg/ml. ZnO nanoparticles exert cytotoxic effects on promastigotes of L. major through the induction of apoptosis. A concentration of 120 μg/ml of ZnO nanoparticles induced 93.76% apoptosis in L. major after 72 hours.

Conclusion

ZnO NPs can induce apoptosis in L. major by dose and time-depended manner in vitro condition.

Keywords: Leishmania major, Amastigote, Promastigote, ZnO nanoparticles, Apoptosis, MTT assay

Introduction

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis is a major public health problem caused by the genus Leishmania and is transmitted by the bite of a sand fly (1). It is endemic in 98 countries and the incidence of this disease is 0.7 to 1.2 million cases annually in the world (2). Cutaneous lesions resulted from development of nodules that converse to ulcerative lesions (3). The drugs which World Health Organization (WHO) recommends for cutaneous leishmaniasis are antimonial compounds (4). These drugs have different side effects; also the recrudescence may occur (5). Also, drug resistance to pentavalent antimonials which have been recommended for the treatment of leishmaniasis has been reported in endemic countries (6). Whereas, there is not any effective vaccine against leishmaniasis; so, investigation to find effective drugs is taken into consideration (5). During the last two decades, many attempts have been made to develop effective new compounds for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) that would be economical, applicable topically to lesions and could avoid development of resistance (7). Cosmetically unacceptable lesions, chronic lesions, large lesions, lesions in immunosuppressed patients, lesions over joints, multiple lesions, nodular lymphangitis and worsening lesions are reasons to treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis (7).

Nanoparticles have unique physicochemical properties such as tiny size, great surface area, electrical charge and shape (8). Metal oxide nanoparticles have different usage in the various sciences (9). The nanoparticles are commonly used in medicine in drug delivery and cancer therapy (10). ZnO is one of the five zinc compounds that are currently listed as generally recognized as safe by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (11). This nanoparticle has an antibacterial effect on gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11, 12). Antibacterial activity of ZnO is attributed to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on the surface of these oxides (13,14). Zinc oxide increases fat oxidation in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell membranes (11) and it is effective on resistant microorganisms (15). Wang et al. (2008) have investigated the fatality rate of zinc oxide, aluminium oxide and titanium oxide on Caenorhabditis elegans nematode eggs (8). Torabi et al. (2011) and Mohebali et al. (2009) have investigated antileishmanial activity of gold and silver nanoparticles on Iranian strain of L. major (16,17).

The present investigation was aimed to evaluate the antileishmanial activity of ZnO nanoparticles on L. major in vitro condition.

Materials and Methods

Nanoparticle

ZnO nanoparticle powder with mean particle size of 20 nanometers (nm) was purchased from Selekchem Company, USA. The stock of ZnO nanoparticle was dispersed in ultrapure water by sonication at 100W and 40 kHz for 40 min for forming homogeneous suspensions. The NPs were then serially diluted in sterile ultrapure water and additionally sonicated for 40 min. Small magnetic bars were placed in the suspensions for stirring during dilution to avoid aggregation and deposition of particles.

Parasite culture

L. major parasites (MRHO/IR/75/ER) prepared from Razi vaccine and serum research institute of Iran. The promastigotes were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 100 units/ml penicillin, streptomycin 100 μg/ml and 20% FBS in a 25 ± 1 °C incubator. The infectivity of the parasites was maintained by serial subcutaneous passage in BALB/c mice.

Anti-promastigote assay

Promastigotes of L. major was cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 15% FBS in 96-well plates in density of 2× 106 cell/ml as triplicate in the presence of 30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml of ZnO nanoparticles and were incubated at 24 °C. In order to evaluate the parasite survival, the multiplication of the promastigotes was determined by counting the cells by hemocytometer chamber (Neubauer chamber) before and after adding the nanoparticles after 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation. In negative control group, promastigotes were cultured as triplicate without ZnO nanoparticles. GraphPad prism5 was used to determine the IC50.

MTT assay

The promastigotes viability was estimated by MTT assay. Leishmania major promastigotes were cultured in 96-well plates (2 × 105 parasites/well) in the presence of 30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml of ZnO nanoparticles and were incubated at 24 °C. Promastigotes without NPs with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% FBS were considered as a control group. Three wells also were considered as blank wells which only contained 100 μl culture medium. After 24, 48 and 72h incubation periods of the wells, 20 μl MTT (5mg/ml) reagent was added per well, then they incubated for 4h at 24 °C in dark room. The cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min and 100 μl DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) was added to pellets and incubated again. After 10 min optical density (OD) of plate was read by an ELISA reader at 540 nm.Viability percentage was calculated by:

Where, AB is OD of blank well, AC is OD of negative control and AT is OD of treated cells.

Anti-amastigote assay

The peritoneal macrophages were isolated from the peritoneum of BALB/c mice by injection the cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and re-aspiration. Isolated macrophages were seeded on a glass coverslip in tissue culture 12-well plates (18) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h.

Non-adherent cells were removed by two washes PBS. Adherent macrophages were infected with the stationary growth phase of promastigotes at a parasite/macrophage ratio of 10:1, then plate incubated for 24h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Non-internalized promastigotes were removed by washing with cold PBS. Infected macrophages were further incubated in the presence or absence (negative control group) concentrations of the ZnO NPs for 24 h and 48 h. Infected macrophages in coverslip were stained with Giemsa stain, and the amastigotes inside the macrophage (100 macrophages per cover slip) were counted under a light microscope.

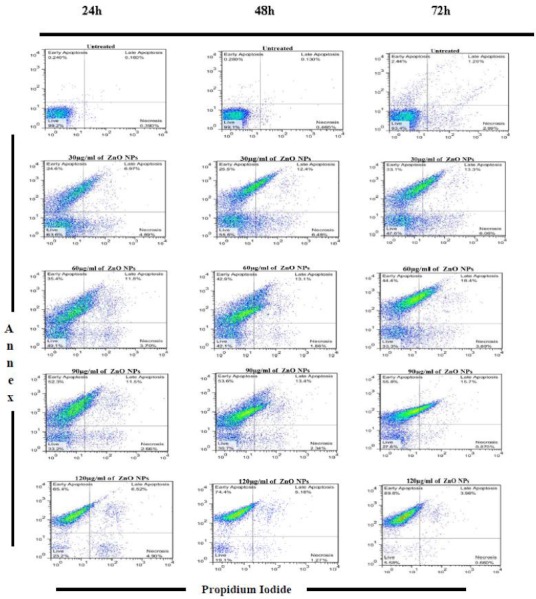

Flow cytometry analysis for inducing apoptosis

The Annexin-V FLUOS Staining Kit (Biovision, USA) was used for the detection of apoptotic and necrotic cells. The promastigotes were cultured in in 24well plates (3 × 105 parasites/well) in the absence (negative control group) and the presence of 30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml of ZnO nanoparticles and were incubated at 24 °C. According to the kit instruction, the promastigotes were collected after 24, 48 and 72h incubation and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min, then supernatant was discharged, and 500μl binding buffer, 5μl annexing and 5μl propidium iodide (PI) were added to the residue. The samples incubated at room temperature and dark situation for 5min. Then they were obtained by BD FACSCanto II and were analysed by FlowJo Software.

Data Analysis

One-way ANOVA were used to analyse the obtained results with SPSS (version 16) software, and a probability (P) value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The effect of ZnO NPs on promastigotes growth

Growth inhibitory effect of four concentrations (30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml) of ZnO NPs on the promastigotes was evaluated at 24, 48 and 72 h (Table 1). The result showed that the growth inhibitory effect is dose dependent where the concentration of 30μg/ml after 24h incubation and the concentration of 120 μg/ml after 72h incubation show minimum and maximum percent of mortality rate, respectively. Statistically significant difference was found between test and control groups. The IC50 of ZnO NPs was measured 37.8 μg/ml.

Table 1.

Mean number (Cell/ml) and percentage of viable parasites after adding different concentrations of ZnO NPs

| ZNO NPs (μg/ml) | Viable parasites | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After 24h | After 48h | After 72h | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 30 | 653750 | 52.3 | 637050 | 46.5 | 600000 | 40 |

| 60 | 473750 | 37.9 | 465800 | 34 | 435000 | 29 |

| 90 | 387500 | 31 | 369900 | 27 | 352500 | 23.5 |

| 120 | 350000 | 28 | 315100 | 23 | 292500 | 19.5 |

| Control | 1250000 | 1370231 | 1505000 | |||

Numbers of promastigotes were counted by hemocytometer chamber (Neubauer chamber) before and after adding the nanoparticles. Viability percentage obtained using number of parasites in test and control groups.

Cytotoxic effect of ZnO NPs on L. major by MTT assay

The cytotoxic effect of ZnO NPs on promastigotes of L. major was evaluated at four concentrations (30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml) for 24, 48 and 72 h. The concentration of 120 μg/ml of ZnO NPs after 72h shows maximum cytotoxic effect on promastigotes of L. major. Result shows, by increasing the NPs concentration, the viability of promastigotes will decrease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Viability percentage of promastigotes following treatment with different concentrations of ZnO NPs

| ZNO NPs | Percent viability of promastigotes after adding Nanoparticles | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrations (μg/ml) | 24h | 48h | 72h |

| 30 | 55 | 50 | 47.8 |

| 60 | 45.3 | 43 | 38.9 |

| 90 | 37.1 | 36 | 31 |

| 120 | 33 | 29.5 | 22 |

Antiamastigote assay

The anti-amastigote activity of ZnO NPs was evaluated in infected macrophage. Result shows, by increasing the NPs concentration, the number of amastigotes in infected macrophage will decrease. Mean number of amastigotes /macrophage after 48h in the negative control group were 4.8 and in 30 μg/ml and 120 μg/ml of ZnO NPs groups were 1.5 and 0.8, respectively (Table 3). These results showed the significant reduction of mean number of amastigotes in test groups compared to the control groups.

Table 3.

Mean numbers of amastigote /macrophage at 24 and 48h after treatment with different concentrations of ZnO NPs

| ZNO NPs | Mean number of amastigote/macrophage | |

|---|---|---|

| Concentrations(μg/ml) | 24h | 48h |

| 30 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| 60 | 1.47 | 1.3 |

| 90 | 1.2 | 1.12 |

| 120 | 0.95 | 0.8 |

| Control | 4.3 | 4.8 |

Induced apoptosis by ZnO NPs

Flow cytometric analysis shows, following treatment of promastigotes with four concentrations (30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml) of ZnO NPs for 24, 48 and 72 h, necrotic and apoptotic effects in the parasite were emerged. The percent of apoptosis (Early and Late Apoptosis) in promastigotes induced by 30, 60, 90 and 120 μg/ml of ZnO NPs after 24 h was 31.57%, 47.2%, 63.8% and 71.92%, respectively. Induced apoptosis (Early and Late Apoptosis) in promastigotes after 48h was 37.9%, 56%, 67% and 79.58% respectively, and after 72h was 46.4%, 62.8%, 71.5% and 93.76% respectively, (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Flow cytometry result. Promastigotes staining with Annexin V and Propidium Iodide after treatment with different concentrations of ZnO NPs in three periods of time (24, 48 and 72 h)

Discussion

Antimonial compounds are the drugs of choice for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis, whereas amphotericin B and pentamidine or miltefosin is being used as alternative drugs (4, 19). Use of pentavalent antimonials to treat leishmaniasis is associated with a range of cardiac, biochemical and blood factors adverse effects (20, 21). The result of a study conducted on an Iranian strain of L. major showed that miltefosine has a good activity against L. major and it is suggested as effective anti-leishmanial agent (19). Also, miltefosine effectiveness in treating cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. major compared to meglumine antimoniate was evaluated in a clinical trial (22) in 2007. The results showed that miltefosine is apparently at least as good as meglumine antimoniate in cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment (22). But, all of these medicines have different toxic effects and show some resistance to the infection. Therefore, there is an urgent need to find a new anti-leishmaniasis drug (4).

Since the nanoparticles have potential in the search for new agents against different microorganisms. In the present study, we examined leishmanicidal activity of ZnO NPs on the Iranian strain of L. major. To our knowledge, based on a search on the literature, no studies have been conducted on the cytotoxity effects of ZnO NPs on L. major in vitro. In this work, a relevant viability test (MTT) was used to evaluate the cytotoxic effect of ZnO NPs on L.major promastigotes.

Results of this study showed that ZnO NPs have dose-dependent anti-leishmanial activities. Counting number of parasites indicated statistically significant difference between test and control groups. Other nanoparticles such as nanogold, nanosilver and nanoselenium similarly have been reported possess antileishmanial activities on L. major and L. infantum (16,17,23). Based on the previous studies, ZnO NPs have many effects on the vast amount of microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. Furthermore ZnO nanoparticles as one of the multifunctional inorganic nanoparticles has many significant features such as chemical and physical stability, high catalysis activity, with varied applications as semiconductors, sensors, solar cells, etc. (12).

Some other anti-Leishmania drugs like Miltefosine can induce apoptosis in Leishmania. Miltefosine induces apoptosis in L. donovani through increasing cytochrome c releasing, followed by mitochondrial membrane permeability reduction (24). But antileishmanial mechanism of ZnO NPs is yet unknown. According to other studies, the drug has lethal effects against cancer cells and fibroblasts. According to the Ahamed et al. results, ZnO nanorod induces apoptosis in human alveolar adenocarcinoma cells via p53, surviving and Bax/bcl-2 pathways (9). However, ZnO NPs have been reported that can induce apoptosis in human dermal fibroblasts (25) and cell death in human mesothelioma and rodent fibroblasts (26).

Conclusion

ZnO NPs can induce apoptosis in L. major by dose and time-depended manner in vitro condition. Search for the antileishmanial mechanism of ZnO NPs can be an interesting subject for study in the future.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of PhD thesis supported financially by Tarbiat Modares University. The authors wish to thank the Research Department as well as Dr Pirestani for their assistance. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Makwali JA, Wanjala FME, Kaburi JC, Ingonga J, Byrum WW, Anjili CO. Combination and monotherapy of Leishmania major infection in BALB/c mice using plant extracts and herbicide. J Vector Borne Dis. 2012;49(3):123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35671. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garnier T, Croft SL. Topical treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3(4):538–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minodier P, Parola P. Cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2006;5(3):150–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma NK, Dey CS. Possible Mechanism of Miltefosine-Mediated Death of Leishmania donovani. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3010–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3010-3015.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Natera S, Machuca C, Padron-Nieves M, Romero A, Diaz E, Ponte-Sucre A. Leishmania spp.: proficiency of drug-resistant parasites. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29(6):637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markle WH, Makhoul K. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Recognition and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:455–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Wick RL, Xing B. Toxicity of nanoparticulate and bulk ZnO, Al2O3 and TiO2 to the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ Pollut. 2008;157:1171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahamed M, Akhtar JM, Raja M, Ahmad I, Siddiqui MKJ, AlSalhi MS, Alrokayan SA. ZnO nanorod induced apoptosis in human alveolar adenocarcinoma cells via p53, survivin and bax/bcl-2 pathways: role of oxidative stress. Nanomedicine :NBM. 2011;7:904–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nair S, Sasidharan A, Divya RVV, Menon D, Nair S, Manzoor K, et al. Role of size scale of ZnO nanoparticles and microparticles on toxicity toward bacteria and osteoblast cancer cells. J Mater Sci. 2008;20:235–41. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Premanathan M, Karthikeyan K, Jeyasubramanian K, Manivannan G. Selective toxicity of ZnO nanoparticles toward Gram-positive bacteria and cancer cells by apoptosis through lipid peroxidation. Nanomedicine. 2011;7:184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emami-Karvani Z, Chehrazi P. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticle on gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:1368–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawai J. Quantitative evaluation of antibacterial activities of metallic oxide powders (ZnO, MgO and CaO) by conductimetric assay. J Microbiol Meth. 2003;54:177–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(03)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawai J, Yoshikawa T. Quantitative evaluation of antifungal activity of metallic oxide powders (MgO, CaO and ZnO) by an indirect conductimetric assay. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:803–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirota K, Sugimoto M, Kato M, Tsukagoshi K, Tanigawa T, Sugimoto H. Preparation of zinc oxide ceramics with a sustainable antibacterial activity under dark conditions. Ceram Int. 2010;36:497–506. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torabi N, Mohebali M, Shahverdi AR, Rezayat SM, Edrissian GH, Esmaeili J, et al. Nanogold for the treatment of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER): an animal trial with methanol extract of Eucalyptus camaldulensis. J Pharm Sci. 2011:113–16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohebali M, Rezayat MM, Gilani K, Sarkar S, Akhoundi B, Esmaeili J, Satvat T, Elikaee S, Charehdar S, Hooshyar H. Nanosilver in the treatment of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major (MRHO/-IR/75/ER): an in vitro and in vivo study. Daru. 2009;17(4):285–289. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love DC, Esko JD, Mosser DM. Heparin-binding Activity on Leishmania Amastigote Which Mediates Adhesion to Cellular Proteoglycans. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:759–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.3.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmaeili J, Mohebali M, Edrissian GH, Rezayat SM, Ghazi-Khansari M, Charehdar S. Evaluation of miltefosine against Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER): In vitro and In vivo studies. Acta Med Iranica. 2008;46(3):191–196. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanehsaz SM, Ishkhanian S. Electrocardiographic and biochemical Adverse Effects of Meglumine Antimoniate during the Treatment of Syrian Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Patients. EDOJ. 2013;9(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayatollahi J, Modares mosadegh M, Halvani A. Effect of Glucantime on blood factors in patients with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Iran J Ped Hematol Oncol. 2011;1(2):57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohebali M, Fotouhi A, Hooshmand B, Zarei Z, Akhoundi B, Rahnema A, et al. Comparison of miltefosine and meglumine antimoniate for the treatment of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) by a randomized clinical trial in Iran. Acta Tro. 2007;103(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soflaei N, Dalimi A, Abdoli A, Kamali M, Nasiri V, Shakibaie M, et al. Anti-leishmanial activities of selenium nanoparticles and selenium dioxide on Leishmania infantum. Comp Clin Pathol. 2012 DOI 10.1007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verma NK, Singh G, Dey CS. Miltefosine induces apoptosis in arsenite-resistant Leishmania donovani promastigotes through mitochondrial dysfunction. Exp Parasitol. 2007;116:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer K, Rajanahalli P, Ahamed M, Rowe JJ, Hong Y. ZnO nanoparticles induce apoptosis in human dermal fibroblasts via p53 and p38 pathways. Toxicol in Vitro. 2011;25:1721–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner TJ, Wick P, Manser P, Spohn P, Grass RN, Limbach LK, et al. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Oxide Nanoparticles: Comparison to Asbestos, Silica, and the Effect of Particle Solubility. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:4374–81. doi: 10.1021/es052069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]