Abstract

Background:

The reports on efficacy of oral hydration treatment for the prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CIAKI) in elective radiological procedures and cardiac catheterization remain controversial.

Aims:

The objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the use of oral hydration regimen for prevention of CIAKI.

Materials and Methods:

Comprehensive literature searches for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of outpatient oral hydration treatment was performed using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Systematic Reviews, and clinicaltrials.gov from inception until July 4th, 2014. Primary outcome was the incidence of CIAKI.

Results:

Six prospective RCTs were included in our analysis. Of 513patients undergoing elective procedures with contrast exposures,45 patients (8.8%) had CIAKI. Of 241 patients with oral hydration regimen, 23 (9.5%) developed CIAKI. Of 272 patients with intravenous (IV) fluid regimen, 22 (8.1%) had CIAKI. Study populations in all included studies had relatively normal kidney function to chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 3. There was no significant increased risk of CIAKI in oral fluid regimen group compared toIV fluid regimen group (RR = 0.94, 95% confidence interval, CI = 0.38-2.31).

Conclusions:

According to our analysis,there is no evidence that oral fluid regimen is associated with more risk of CIAKI in patients undergoing elective procedures with contrast exposures compared to IV fluid regimen. This finding suggests that the oral fluid regimen might be considered as a possible outpatient treatment option for CIAKI prevention in patients with normal to moderately reduced kidney function.

Keywords: Contrast-induced Nephropathy, Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury, Elective cardiac catheterization, Meta-analysis, Oral Hydration

Introduction

Contrast-induced nephropathy or contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CIAKI) is a well-recognized complication of radiological interventions, cardiac catheterization, or minimally invasive procedures that require iodinated contrast administration. A commonly used definition for CIAKI is as serum creatinine (SCr) elevation of 0.5 mg/dL or an increase of more than 25% from the baseline SCr value in the absence of an alternative cause.[1]

CIAKI is a common cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) in an inpatient setting.[2] Its incidence has been reported from 2% in the general population without risk factors to more than 40% in high-risk patients.[3,4,5,6,7,8] The incident rate of CIAKI is approximately 150,000 patients each year in the world, and at least 1% requires renal replacement therapy (RRT).[9]

In the outpatient setting, Kim et al. demonstrated that CIAKI occurred in 2.5% of chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients after contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT). The development of CIAKIwas associated with poor kidney survival in the long-term and also increased the risk of RRT, especially in patients with CKD stage 4-5 (glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2),[10] The risk of CIAKI is also associated with the type of procedures, with 14.5% overall in patients undergoing coronary interventions compared to 1.6-2.3% for radiological diagnostic intervention.[11]

The efficacy of oral hydration or oral sodium chloride loading for the prevention of CIAKI in patients who receive contrast as outpatients or elective radiological procedures is still conflicting. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) study found a higher rate of AKI in patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization who received oral fluid regimen than those who received intravenous (IV) normal saline.[12] Conversely, a few studies demonstrated no difference in the incidence of CIAKI between oral fluid hydration group and IV fluid regimen group.[13,14,15,16,17]

The objective of this meta-analysis was to assess the use of oral hydration regimen for prevention of CIAKI in patients after electively radiological procedures with contrast exposures.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

Two investigators (W.C. and C.T.) independently searched published RCTs indexed in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials Systematic Reviews, and clinicaltrials.gov from inception to July 4th, 2014 using the terms “oral hydration” and “oral fluid” combined with the terms “contrast nephropathy,” “contrast-induced nephropathy,” and “contrast-induced acute kidney injury.” A manual search for additional relevant studies using referencesfrom retrieved articles was also performed. Conference abstracts and unpublished studies were excluded.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

RCTs published as original studies to evaluate the incidence of CIAKI in patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization or any radiological procedures with contrast exposures,

Data for analysis for relative risks, hazard ratios, standardized incidence ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were provided,

Reference group composed of participants who used IV fluid regimen and,

Only studies in humans.

Study eligibility was independently determined by the two investigators noted above. Differing decisions were resolved by mutual consensus. The quality of each study was independently evaluated by each investigator using Jadad quality assessment scale.[18]

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was used to extract the following information: last name of the first author, study design, year of study, country of origin, year of publication, sample size, characteristics of included participants, definition of CIAKI, definition of oral fluid and IV fluid regimens, type of contrast, and relative risk with 95% CI. The two investigators mentioned above independently performed this data extraction.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.2 software from the Cochrane Collaboration was used for data analysis. Point estimates and standard errors were extracted from individual studies and were combined by the generic inverse variance method of DerSimonian and Laird.[19] Given the high likelihood of between study variances, we used a random-effect model rather than a fixed-effect model.[20,21,22] Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran's Q test. This statistic is complemented with the I2 statistic, which quantifies the proportion of the total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of I2 of 0-25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, 26-50% low heterogeneity, 51-75% moderate heterogeneity, and >75% high heterogeneity.[23,24]

Results

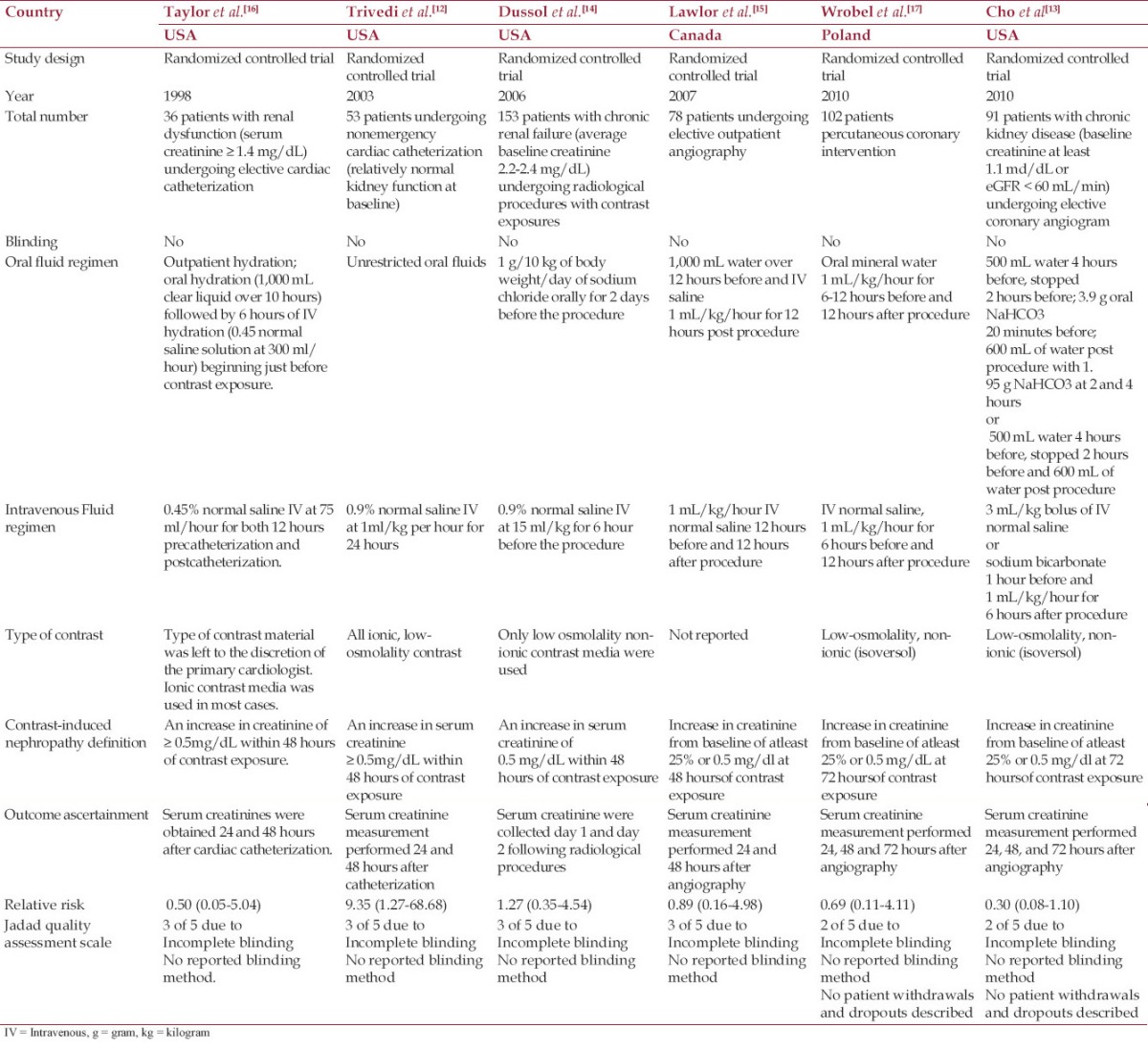

Our search strategy yielded 774 potentially relevant articles. Seven hundred and thirty-six articles were excluded based on title and abstract for clearly not fulfilling inclusion criteria on the basis of the type of article, study design, population, or outcome of interest. Thirty-seven articles underwent full-length-article review. Thirty-one articles were excluded (23 articles used only IV fluid regimen, and eight articles did not report the outcomes of interest). Six RCTs were identified and included in the data analysis.[12,13,14,15,16,17] Table 1 describes the detailed characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included in this meta-analysis

The overall incidence of CIAKI

Of 513 patients who had elective cardiac catheterization or radiological procedures with contrast exposures, 45 patients (8.8%) developed CIAKI. Of 241 patients with oral hydration regimen, 23 (9.5%) developed CIAKI. Of 272 patients with IV fluid regimen, 22 (8.1%) had CIAKI.

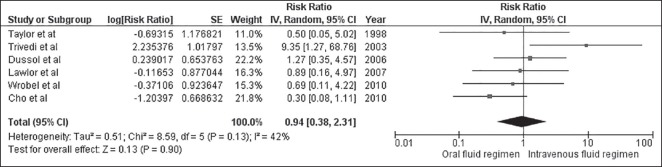

The risk of CIAKI in oral hydration and IV fluid regimens

The pooled risk ratio (RR) of CIAKI in oral hydration regimen versus IV fluid treatment was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.38-2.31). The statistical heterogeneity was moderate with an I2 of 42%. [Figure 1] shows the forest plot of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the included studies comparing the risk of CIAKI in oral hydration and IV fluid regimens

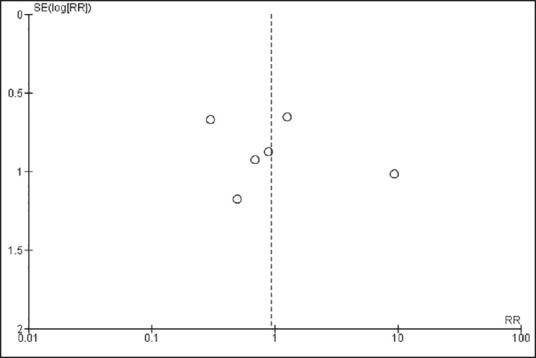

Evaluation for publication bias

Funnel plot to evaluate publication bias for the risk of CIAKI in patients receiving oral hydration regimen versus IV fluid regimenis summarized in [Figure 2]. The graphshows no obvious asymmetry and, thus, provide a suggestion to the absence of publication bias.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of 6 studies to evaluate publication bias for the risk of CIAKI in patients receiving oral hydration regimen versus IV fluid regimen

Discussions

Our meta-analysis showed an overall incidence of CIAKI of 8.8% in patients undergoing elective cardiac catheterization or radiological procedures with contrast exposures. Our study also demonstrated no significant difference between oral fluid hydration and IV fluid hydration regimens in the prevention of CIAKI.

Although there have been heterogeneities of the reported incidence of CIAKI among studies, due to differences in definition, study population, imaging procedure[11], all included studies in our analysis used the same definition of CIAKI (an increase in serum creatinine ≥0.5mg/dL within 48 hours of contrast exposure).[1] Our meta-analysis found higher incident rate of CIAKI of 8.8% in the outpatient setting, compared to 2.5% from the study by Kim et al. in 2010.[10] The higher incidence could be explained by the use of both intra-arterial and IV contrast in our included studies in the analysis compared to the main use of IV contrast in study by Kim et al.[10] .

The underlying pathogenesis of CIAKI is not completely explained. It has been observed that a combination of direct toxic injury to the renal tubular cells and ischemic injury (hemodynamic changes of renal blood flow), mediated by increase in free radicals, adenosine and endothelin-induced vasocontriction as well as decrease in nitric oxide and prostaglandin-induced vasodilation.[25]

Although the reported need for RRT in the setting of CIAKI is low as 0.44%[11], patients developing CIAKI have longer hospitalization and higher mortality rates.[3,11] Solomon et al. showed that the long-term adverse event rate was higher in patients developing CIAKI after adjustment for baseline comorbidities.[26] Since no specific treatments are currently available when AKI has occurred, studies have focused on the prevention of CIAKI.

Acetylcysteine has been studied for CIAKI prevention as it potentially reduces both vasoconstriction and oxygen-free radical generation after contrast exposure.[27] However,studies have suggested that hydration is still the most effective treatment to prevent CIAKI.[28] Hydration increases urine flow rates,[29] decreases the concentration of contrast media in the tubule, and expedites excretion of contrast media.[30]

For inpatient setting or individuals who require emergent coronary angiography or radiological procedures with contrast exposures, intravenous hydration has been studied and used as first-line treatment for prevention of CIAKI.[31,32] Isotonic saline is preferred to hypotonic solution because isotonic saline is a more efficient volume expander.[32] The use of IV sodium bicarbonate compared to IV isotonic saline has been examined in a number of randomized trials and meta-analyses[33] since alkalinization may protect against free radical injury. However, the results remain conflicting.

In the outpatient setting, our analysis suggests that the oral fluid regimen is not significantly inferior to IV fluid regimen. A recent systematic review raised a very important point that oral hydration may be as effective as IV fluid for CIAKI prevention.[34] Even in patients with CKD stage 3, studies by Talor et al.[16] and Dussol et al.[14] showed that outpatient hydration and oral salt loading prior to the contrast exposures are similar in term of CIAKI prevention compared with IV hydration. However, unrestricted oral fluids only, without encouraged oral fluid hydration or additional salt intake, may not be enough, and could potentially increase the risk of CIAKI compared to IV fluid hydration with isotonic saline.[12]

Although almost all included studies were of moderate to high quality[12,14,15,16] (as evaluated by Jadad quality assessment scale), there are some limitations. Firstly, study populations in all included studies had relatively normal kidney function to CKD stage 3. Therefore, the finding of our study can notbe generalized to the individuals with moderate to severe CKD (stage 4-5). Secondly, all included studies used fixed rates of chloride based IV fluid as the control groups [Table 1]. Therefore, we could not demonstrate the comparison with other IV solutions, such as IV sodium bicarbonate, or with a higher rate of IV isotonic saline. Recently, the POSEIDON randomized controlled trial[35] showed that the use of different IV isotonic saline rates guided by end-diastolic pressure for CIAKI prevention is effective in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization. Although, our study could not compare oral fluid hydration regimen to IV isotonic saline guided by end-diastolic pressure for CIAKI prevention, oral fluid hydration is a reasonable strategy for patients with low risks[36] for CIAKI undergoing radiological procedures with IV contrast that do not have central venous catheter to assess end-diastolic pressure.

Despite no significant publication bias, there are moderate degrees of heterogeneity in our complete analysis. The potential sources of these heterogeneities include the difference in oral fluid regimen, IV fluid regimen and rate of IV fluid, and the type of contrast media. Moreover the definition of acute kidney injury[37,38,39] also varies among included studies. However, the strength of our meta-analysis is only RCTs were included, which minimized the potential confounders.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates no statistical significance in increased risks of CIAKI in oral fluid treatment in patients undergoing elective procedures with contrast exposures compared with IV fluid regimen. This finding suggests that the oral fluid regimen might be considered as a possible outpatient treatment option for CIAKI prevention in patients with normal to moderately reduced kidney function.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Harjai KJ, Raizada A, Shenoy C, Sattur S, Orshaw P, Yaeger K, et al. A comparison of contemporary definitions of contrast nephropathy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and a proposal for a novel nephropathy grading system. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pires de Freitas do Carmo L, Macedo E. Contrast-induced nephropathy: Attributable incidence and potential harm. Crit Care. 2012;16:127. doi: 10.1186/cc11327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marenzi G, Lauri G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, De Metrio M, Marana I, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briguori C, Airoldi F, D'Andrea D, Bonizzoni E, Morici N, Focaccio A, et al. Renal Insufficiency Following Contrast Media Administration Trial (Remedial): A randomized comparison of 3 preventive strategies. Circulation. 2007;115:1211–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.687152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Marana I, Lauri G, Campodonico J, Grazi M, et al. N-acetylcysteine and contrast-induced nephropathy in primary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2773–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tepel M, van der Giet M, Schwarzfeld C, Laufer U, Liermann D, Zidek W. Prevention of radiographic-contrast-agent-induced reductions in renal function by acetylcysteine. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:180–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AM, Jones AE, Tumlin JA, Kline JA. Incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy after contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the outpatient setting. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:4–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05200709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huber W, Eckel F, Hennig M, Rosenbrock H, Wacker A, Saur D, et al. Prophylaxis of contrast material-induced nephropathy in patients in intensive care: Acetylcysteine, theophylline, or both. A randomized study? Radiology. 2006;239:793–804. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2393041456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldkamp T, Kribben A. Contrast media induced nephropathy: Definition, incidence, outcome, pathophysiology, risk factors and prevention. Minerva Med. 2008;99:177–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SM, Cha RH, Lee JP, Kim DK, Oh KH, Joo KW, et al. Incidence and outcomes of contrast-induced nephropathy after computed tomography in patients with CKD: A quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:1018–25. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCullough PA, Wolyn R, Rocher LL, Levin RN, O'Neill WW. Acute renal failure after coronary intervention: Incidence, risk factors, and relationship to mortality. Am J Med. 1997;103:368–75. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi HS, Moore H, Nasr S, Aggarwal K, Agrawal A, Goel P, et al. A randomized prospective trial to assess the role of saline hydration on the development of contrast nephrotoxicity. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;93:C29–34. doi: 10.1159/000066641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho R, Javed N, Traub D, Kodali S, Atem F, Srinivasan V. Oral hydration and alkalinization is noninferior to intravenous therapy for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Interv Cardiol. 2010;23:460–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2010.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dussol B, Morange S, Loundoun A, Auquier P, Berland Y. A randomized trial of saline hydration to prevent contrast nephropathy in chronic renal failure patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2120–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawlor DK, Moist L, DeRose G, Harris KA, Lovell MB, Kribs SW, et al. Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in vascular surgery patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 2007;21:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor AJ, Hotchkiss D, Morse RW, McCabe J. PREPARED: Preparation for angiography in renal dysfunction: A randomized trial of inpatient vs outpatient hydration protocols for cardiac catheterization in mild-to-moderate renal dysfunction. Chest. 1998;114:1570–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wrobel W, Sinkiewicz W, Gordon M, Wozniak-Wisniewska A. Oral versus intravenous hydration and renal function in diabetic patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Kardiol Pol. 2010;68:1015–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, O'Corragain OA, Edmonds PJ, Ungprasert P, Kittanamongkolchai W, et al. The risk of kidney cancer in patients with kidney stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 2014 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcu195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ungprasert P, Srivali N, Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Knight EL. Is the incidence of malignancy increased in patients with sarcoidosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis? Respirology. 2014;19:993–8. doi: 10.1111/resp.12369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ungprasert P, Charoenpong P, Ratanasrimetha P, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, Suksaranjit P. Risk of coronary artery disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:1099–104. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2681-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, O Corragain OA, Edmonds PJ, Kittanamongkolchai W, Erickson SB. Associations of sugar and artificially sweetened soda and chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2014 doi: 10.1111/nep.12343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katholi RE, Woods WT, Jr, Taylor GJ, Deitrick CL, Womack KA, Katholi CR, et al. Oxygen free radicals and contrast nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:64–71. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon RJ, Mehran R, Natarajan MK, Doucet S, Katholi RE, Staniloae CS, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy and long-term adverse events: Cause and effect? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1162–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00550109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birck R, Krzossok S, Markowetz F, Schnulle P, van der Woude FJ, Braun C. Acetylcysteine for prevention of contrast nephropathy: Meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;362:598–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14189-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson PB, Hansell P, Liss P. Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stevens MA, McCullough PA, Tobin KJ, Speck JP, Westveer DC, Guido-Allen DA, et al. A prospective randomized trial of prevention measures in patients at high risk for contrast nephropathy: Results of the P.R.I.N.C.E. Study. Prevention of Radiocontrast Induced Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano G, Briguori C, Quintavalle C, Zanca C, Rivera NV, Colombo A, et al. Contrast agents and renal cell apoptosis. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2569–76. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueller C, Buerkle G, Buettner HJ, Petersen J, Perruchoud AP, Eriksson U, et al. Prevention of contrast media-associated nephropathy: Randomized comparison of 2 hydration regimens in 1620 patients undergoing coronary angioplasty. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:329–36. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weisbord SD, Palevsky PM. Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy with volume expansion. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:273–80. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02580607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoste EA, De Waele JJ, Gevaert SA, Uchino S, Kellum JA. Sodium bicarbonate for prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:747–58. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hiremath S, Akbari A, Shabana W, Fergusson DA, Knoll GA. Prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: Is simple oral hydration similar to intravenous. A systematic review of the evidence? PLoS One. 2013;8:e60009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brar SS, Aharonian V, Mansukhani P, Moore N, Shen AY, Jorgensen M, et al. Haemodynamic-guided fluid administration for the prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: The POSEIDON randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1814–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60689-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, Fahy M, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: Development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thongprayoon C, Spanuchart I, Cheungpasitporn W, Kangwanpornsiri A. Idiopathic retroperitoneal fibrosis: A challenging case in a rare disease. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:237–8. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.132945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheungpasitporn W, Horne JM, Howarth CB. Adrenocortical carcinoma presenting as varicocele and renal vein thrombosis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:337. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheungpasitporn W, Jirajariyavej T, Howarth CB, Rosen RM. Henoch-schonlein purpura in an older man presenting as rectal bleeding and IgA mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:364. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]