Abstract

Osteopetrosis is a rare inherited bone disease where bones harden and become abnormally dense. While the diagnosis is clinical, it also greatly relies on appearance of the skeleton radiographically. X-ray, radionuclide bone scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging have been reported to identify characteristics of osteopetrosis. We present an interesting case of a 59-year-old man with a history of bilateral hip fractures. He underwent 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate whole body scan supplemented with single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of spine, which showed increased uptake in the humeri, tibiae and femora, which were in keeping with osteopetrosis.

Keywords: Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, osteopetrosis, single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography

INTRODUCTION

Osteopetrosis, translated as “stone bone,” is a rare inherited bone disease. It is also known as marble bone disease where bones harden and become abnormally dense, opposite to osteoporosis where bones become less dense and more brittle, or osteomalacia where bones soften. Various modalities of imaging have been shown to be useful in detecting and diagnosing osteopetrosis.

CASE REPORT

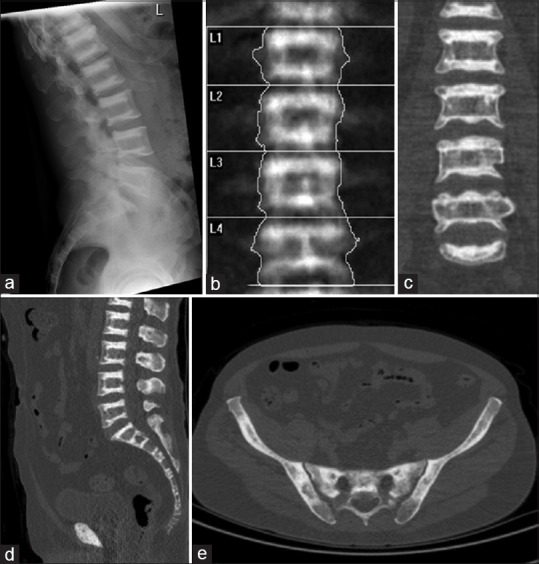

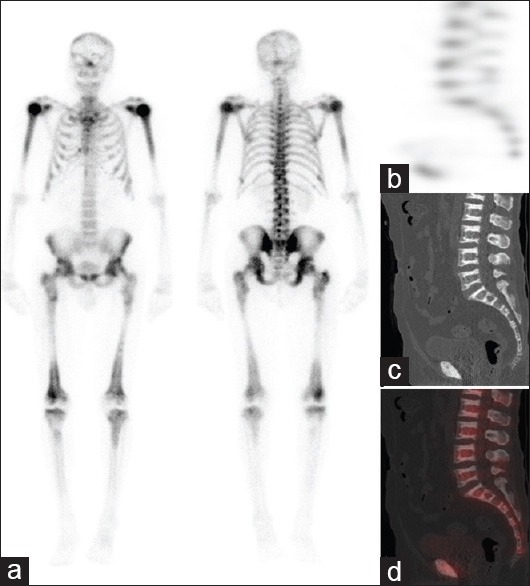

A 59-year-old man with the previous history of bilateral hip fractures was referred for a bone scan to rule out osteopetrosis and assess site of increased metabolic activity. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan revealed high bone density [Figure 1b and c]. Patient underwent 99mTc-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) whole body scan supplemented with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/computed tomography (CT) of the spine. 99mTc-MDP bone scan showed increased tracer uptake at the proximal ends of humeri and tibiae, proximal and distal ends of femora [Figure 2a]. Linear uptake in the proximal femora and several lower ribs bilaterally was also noted and suggestive of fractures. SPECT images of the spine were unremarkable [Figure 2b]. CT scan showed dense sclerosis at the margins of the vertebral bodies (bone-in-bone appearance) and within the pelvic bones [Figure 1d and e]. The overall bone scan and SPECT/CT appearances were in keeping with osteopetrosis.

Figure 1.

(a) X-ray of spine shows dense and sclerosis at the margins of the vertebral bodies in alternating parallel sclerotic and lucent bands (sandwich vertebrae or “rugger-jersey” spine). (b) Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan shows dense sclerosis at the margins of the vertebral bodies and the T-score was high at +6.5 (b and c). On computed tomography (CT) component of single-photon emission computed tomography/CT, there is dense sclerosis at the margins of the vertebral bodies (bone-in-bone appearance) and within the pelvic bones (d and e)

Figure 2.

99mTc-methylene diphosphonate bone scan shows increased tracer uptake at the proximal ends of humeri and tibiae along with proximal and distal ends of femora. Linear uptake at the proximal femora and several lower ribs bilaterally is suggestive of fracture at these sites

DISCUSSION

Etiology

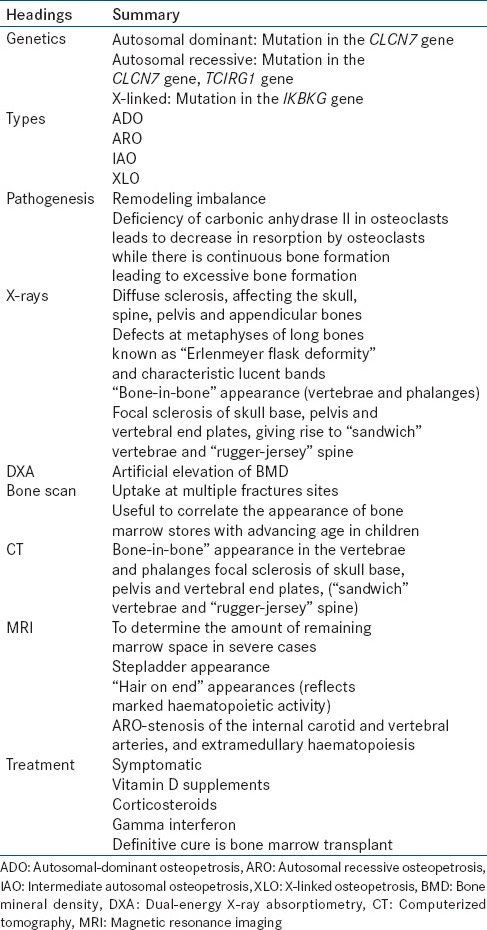

Several different types of osteopetrosis have been described, distinguished by the pattern of inheritance – autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked.[1] [Table 1].

Table 1.

Autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (ADO) is also known as Albers-Schönberg disease after first being described in 1904. Typically in the mildest form of the disorder, affected individuals may show no symptoms. The incidence is 1:20000, and a mutation in the CLCN7 gene is responsible for 75% of ADO.[2] Due to its benign symptoms, ADO is usually discovered by accident when X-ray is done for another reason. Clinical manifestations become apparent in late childhood or adolescence; symptoms include: Multiple bone fractures, scoliosis, arthritis, and osteomyelitis.

Autosomal recessive osteopetrosis (ARO) has an incidence of 1:250000. CLCN7 gene was identified in 10–15% of ARO cases, and TCIRG1 gene in 50% of cases.[3] It is of a more severe form and usually happens in early infancy. Dense skull bones compress on nerves in the head and neck, resulting in vision loss, hearing loss, dental abnormalities and paralysis of facial muscles. Dense bones can also impair bone marrow function, causing haematological complications such as abnormal bleeding, anaemia and recurrent infections, which in turn results in hepatosplenomegaly.

Intermediate autosomal osteopetrosis (IAO) is a spectrum that ranges between severe ARO and mild ADO. The affected individual can have either autosomal-dominant or autosomal-recessive pattern inheritance. Signs become noticeable in childhood and include increased risk of bone fracture. In general, they do not have life-threatening bone marrow abnormalities, but calcifications in the brain can cause intellectual disability, and patients may also present with renal tubular acidosis.

X-linked osteopetrosis is rare and is due to mutation in the IKBKG gene.[4] It is characterized by lymphedema and anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. Individuals with this condition also have immunodeficiency, which allows severe and recurrent infections to develop.

Pathogenesis

Normal bone growth is regulated by a balance between bone formation by osteoblasts and bone resorption by osteoclasts. In osteopetrosis, gene mutations cause failure of the resorptive process and hence a remodeling imbalance. The exact mechanism is unknown, however deficiency of carbonic anhydrase II is noted in osteoclasts of affected patients. Carbonic anhydrases catalyze the formation of carbonic acid from carbon dioxide and water. Carbonic acid then dissociates to produce protons, which makes the resorption lacunae acidic. Absence of this enzyme causes defective hydrogen ion pumping, which reduces resorption by osteoclasts, as an acidic environment is required for dissociation of calcium hydroxyapatite from bone matrix.[3] Hence, bone resorption fails while there is continuous formation, forming excessive bone.

Imaging

Diagnosis of osteopetrosis is clinical, based on history and physical examination showing bone defects. It also relies greatly on appearance of the skeleton radiographically [Table 1].

On plain radiographs, osteopetrosis can present as osteosclerosis or dense bones [Figure 1a]. Four classic features appear in radiographs of patients with ADO: (1) Diffuse sclerosis, affecting the skull, spine, pelvis and appendicular bones; (2) Metaphysic long bone defects known as “Erlenmeyer flask deformity,” and characteristic lucent bands; (3) “bone-in-bone” appearance of the vertebrae and phalanges; and (4) sclerosis of skull base, pelvis and vertebral end plates, giving rise to “sandwich” vertebrae, and “rugger-jersey” spine.[2] The appearance on radiographs can further differentiate ADO into two subtypes. Type I shows pronounced sclerosis of the skull with enlarged thickness of the cranial wall, and type II shows more sclerosis at the base.[5]

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry is a method of measuring bone mineral density (BMD). It gives quantitative measures and shows elevation of BMD in patients with osteopetrosis[6] [Figure 1b]. It is considered a safe and noninvasive means of assessing disease progression and response after treatment.

Radiotracers have also been used to assess osteopetrosis. 99mTc-sulfur colloid scintigraphy is best used to show bone marrow distribution of the disease. 99mTc-MDP is used to show uptake at multiple fracture sites and at splayed metaphyses of long bones. Elster et al. also showed that it is possible to use 99mTc-MDP to correlate the appearance of bone marrow stores with advancing age in children[7] [Figure 2a]. Further, the bone scan is useful to assess fracture sites and SPECT/CT, help in accurate localisation, and to confirm or exclude any abnormal sites of increased metabolic activity.

99mTc-human serum albumin (HSA), microspheres are used to demonstrate absence of bone marrow activity, hepatosplenomegaly and sites of extramedullary haematopoiesis, and may be helpful in monitoring effectiveness of therapy after treatment.[8]

Computed tomography scan often shows increased area of bone density [Figure 1d and e], “bone-in-bone” appearance in the vertebrae and phalanges, and sometimes focal sclerosis of skull base, pelvis and vertebral end plates, giving rise to “sandwich” vertebrae, and “rugger-jersey” spine [Figure 1d].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used in more severe cases of osteopetrosis to determine the amount of remaining marrow space. The characteristic appearance shows alternating lack of signal with signal similar to intervertebral discs in the marrow, giving a “stepladder appearance.” There may also be “hair on end” appearances that reflect marked haematopoietic activity.[7] A recent MRI study with 47 affected patients showed sclerosis and thickening of the calvaria in all patients. However, there were two features that showed exclusively in patients with ARO – stenosis of the internal carotid and vertebral arteries, and extramedullary haematopoiesis, which is probably due to the earlier age of onset in ARO and greater severity in this form of the disease.[9]

Treatment

Treatment of this disease is largely based on symptoms.[2] While some may be asymptomatic, many of these patients require orthopaedic surgery at some point in their lives for fractures. The only definitive cure for osteopetrosis is bone marrow transplant,[10] but other medications are also used in nonsurgical management. Vitamin D supplements can be used to stimulate dormant osteoclasts, increasing bone resorption. Corticosteroids are recommended to stimulate bone resorption and to treat anaemia,[11] along with erythropoietin. Gamma interferon has also been shown to be effective in improving immunity, increasing bone resorption and enlarging marrow space.[12]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balemans W, Van Wesenbeeck L, Van Hul W. A clinical and molecular overview of the human osteopetroses. Calcif Tissue Int. 2005;77:263–74. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stark Z, Savarirayan R. Osteopetrosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frattini A, Pangrazio A, Susani L, Sobacchi C, Mirolo M, Abinun M, et al. Chloride channel ClCN7 mutations are responsible for severe recessive, dominant, and intermediate osteopetrosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1740–7. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Döffinger R, Smahi A, Bessia C, Geissmann F, Feinberg J, Durandy A, et al. X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-kappaB signaling. Nat Genet. 2001;27:277–85. doi: 10.1038/85837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bollerslev J, Andersen PE., Jr Radiological, biochemical and hereditary evidence of two types of autosomal dominant osteopetrosis. Bone. 1988;9:7–13. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(88)90021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaste SC, Kasow KA, Horwitz EM. Quantitative bone mineral density assessment in malignant infantile osteopetrosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:181–5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elster AD, Theros EG, Key LL, Stanton C. Autosomal recessive osteopetrosis: Bone marrow imaging. Radiology. 1992;182:507–14. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.2.1732971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thelen MH, Eschmann SM, Moll-Kotowski M, Dopfer R, Bares R. Bone marrow scintigraphy with technetium-99m anti-NCA-95 to monitor therapy in malignant osteopetrosis. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1033–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curé JK, Key LL, Goltra DD, VanTassel P. Cranial MR imaging of osteopetrosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1110–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerritsen EJ, Vossen JM, Fasth A, Friedrich W, Morgan G, Padmos A, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for autosomal recessive osteopetrosis. A report from the Working Party on Inborn Errors of the European Bone Marrow Transplantation Group. J Pediatr. 1994;125:896–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohn A, Capanna R, Delli Pizzi C, Morgese G, Chiarelli F. Autosomal malignant osteopetrosis. From diagnosis to therapy. Minerva Pediatr. 2004;56:115–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Key LL, Jr, Rodriguiz RM, Willi SM, Wright NM, Hatcher HC, Eyre DR, et al. Long-term treatment of osteopetrosis with recombinant human interferon gamma. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1594–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]