Abstract

Pre-coccygeal ganglioneuroma is a rare clinical entity that presents incidentally or with non-specific symptoms. We present a case of a 25 year old housewife who was incidentally diagnosed with pre-coccygeal ganglioneuroma while getting investigated for primary infertility. The patient had no specific complaints except for irregular menstruation which had started 8 months back. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was suggestive of a presacral and pre-coccygeal lesion. Resection of the tumor was done through the anterior approach using the da Vinci Si robotic system. Two robotic arms and one assistant port were used to completely excise the tumor. Robotic excision of such a tumor mass located at a relatively inaccessible area allows enhanced precision and 3-dimentional (3D) view avoiding damage to important surrounding structures.

Keywords: Broad ligament, da Vinci surgery, pre-coccygeal ganglioneuroma, retro-rectal space, robotic surgery

INTRODUCTION

Robotic surgical systems have swiftly developed in the recent past. The high definition three-dimensional (3D) optics, enhanced ergonomics, autonomy of camera control and finer precision of the da Vinci surgical system have made dissections in some of the most inaccessible places in the human body easily accessible.[1] A retro-rectal tumor close to the ureters and iliac vessels usually requires a wide exposure and retraction of the peritoneal organs. Robotic surgery makes these complex dissections simpler than conventional laparoscopy. We report the use of the daVinci surgical system for the minimally invasive surgical treatment of a pre-coccygeal tumor mass. The aim of this case report is to present the advantages of robotic excision of such a deep-seated retro-rectal tumor mass.

CASE REPORT

A 25 year old housewife was being investigated for primary infertility and a large solid heterogenous hypoechoic mass with smooth walls posterior to uterus was found on ultrasonography (USG). The treating gynecologist referred her to a tertiary care center for further investigations. She presented to our hospital on 13th November 2013. She was a known case of hypothyroidism on treatment and had irregular menstruation for the last 8 months.

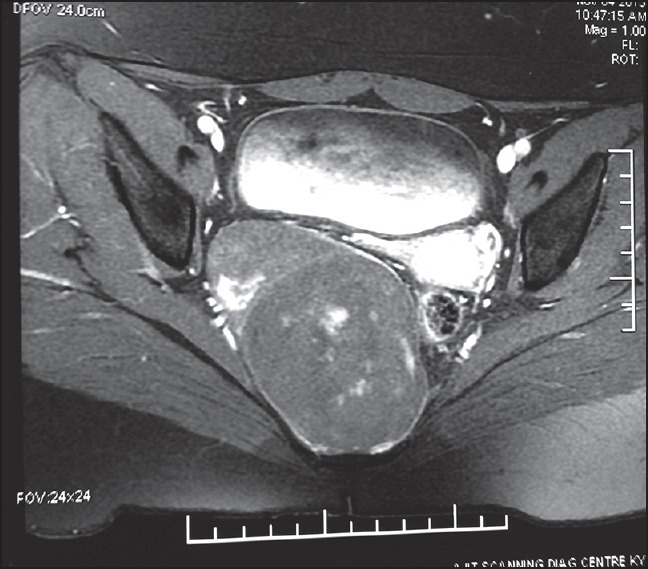

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was advised for further evaluation, which revealed a 9.4 cm × 6.5 cm × 5.7 cm, well-defined thin-walled lesion in the pre-sacral and pre-coccygeal region in the pelvis in midline extending towards the right with displacement of rectum and uterus to the left. It appeared benign on MRI and differential diagnosis of Schwannoma and ganglioneuroma were given [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

MRI- coronal view showing a pre-coccygeal tumor

Figure 2.

MRI- saggital view showing a pre-coccygeal tumor

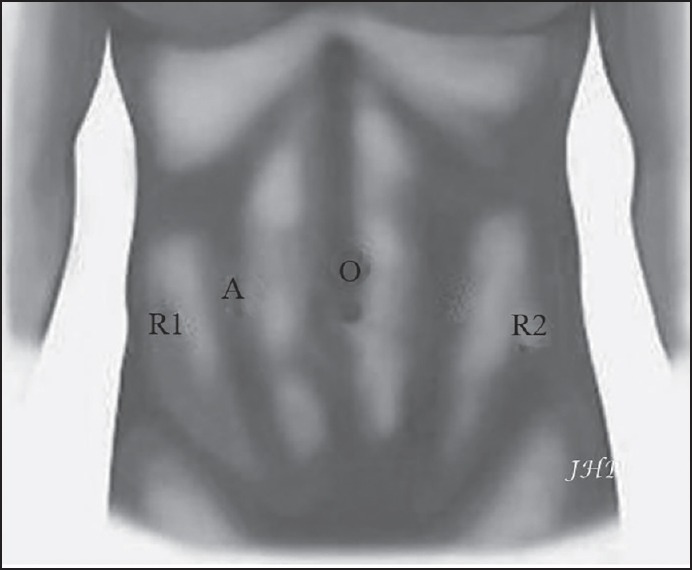

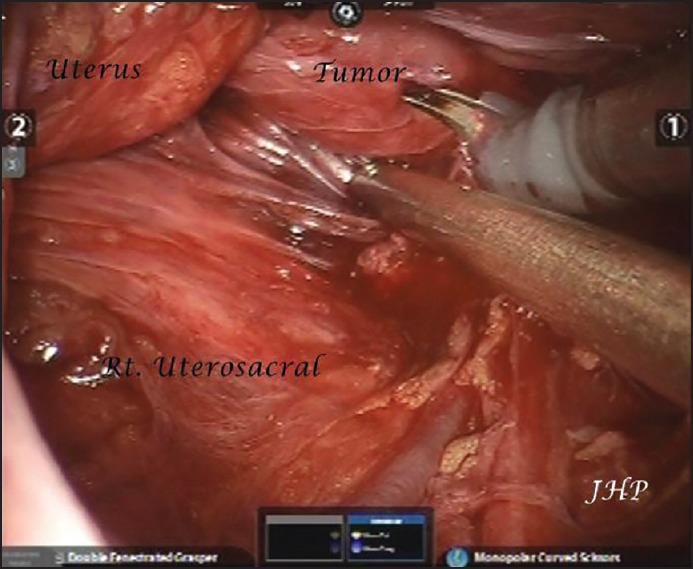

After adequate pre-operative work-up and consultation with a Spine-Neurosurgeon, the patient underwent robotic excision of the tumor on 21st November 2013. The patient was placed in modified Lloyd Davis position. A 12mm supra-umbilical incision was taken and 12mm trocar was introduced. Carbon dioxide pneumo-peritoneum was created. Two da Vinci 8mm ports were introduced, one in the left and other in the right lower quadrants each about 8 cm away from the optic port on either side. Once the trocars were placed, a steep Trendelenberg position with a slight left side downward tilt was given and the robot was docked. The retroperitoneum was accessed by incising the peritoneal fold on the right side of the rectum. The presacral area was dissected and the right parametrium and broad ligament were dissected to identify the tumor mass. An intraoperative laparoscopic USG was done and tumor was localized entering into the fold of the broad ligament on the right side in between the uterosacral ligament, uterus and rectum; and pushing the uterus anteriorly and the rectum laterally as seen on the MRI [Figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3.

Port Position O- Optic port (12 mm) R1- Robotic right arm (8 mm) R2- Robotic left arm (8 mm) A- Assistant port (12 mm)

Figure 4.

Intra-operative image of tumor

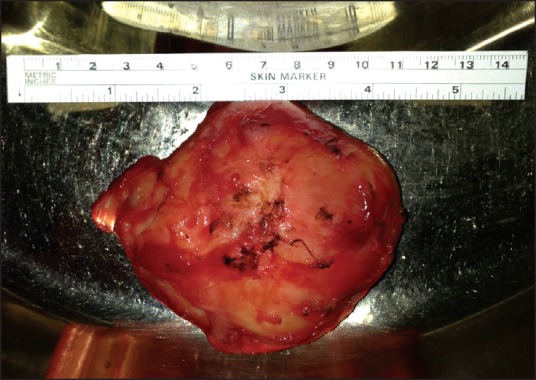

Dissection was done circumferentially around the tumor mass with help of Myoma screw for traction. The base of the tumor was firmly adherent and originated from the nerve root. The specimen was dissected free and removed en masse with help of Endocatch bag after extending the assistant port incision. The console time was 195 min and total blood loss was 40 ml. Pelvic drain was placed. Patient was discharged on post-operative Day 3 after drain removal. Histopathology report confirmed the lesion as a benign ganglioneuroma [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Excised tumor

DISCUSSION

Ganglioneuromas are tumors arising from the sympathetic nervous system and originating from the neural crest cells. These are rare, well-differentiated benign tumors that contain mature ganglion cells, Schwann cells, fibrous tissue and nerve fibers.[2] As ganglioneuromas arise along the sympathetic chain, they are commonly localized in the posterior mediastinum followed by retroperitoneum, cervical region and adrenal gland.[3]

The presacral location is very rare. They are common in young females and present as benign abdominal masses. They are usually asymptomatic until they reach a large size when they cause compressive symptoms and displace adjacent structures. Moreover, several patients can present with constipation or pain due to local mass effect on the rectum, sacral root and lumbosacral plexus.[4] In this patient, the tumor was causing compression on the uterus. Ganglioneuromas usually have a mean diameter of 7 cm. Thus, this patient is a rare case for both its location (presacral and pre-coccygeal) and size, which could be the reason for her infertility. Pelvic ganglioneuromas are not easily diagnosed. The clinical signs and symptoms are not pathognomonic for this pathologic situation. Radiography is essential in evaluating these lesions to determine the optimal surgical approach and the extent of resection.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment as it establishes diagnosis and is therapeutic. The aim of surgery is complete excision of the lesion without damaging the surrounding structures while ensuring minimal morbidity. Posterior surgical approach to manage such lesions is involved with high morbidity and painful recovery, as it requires disarticulation of the coccyx. Anterior approach appears safer as the rectum can be dissected from the anterior aspect of the lesion and then posterior aspect of the lesion is dissected off the presacral fascia.[5,6] Traditional laparoscopy has its limitations due to its 2 dimensional (2D) view and restricted range of movements of laparoscopic instruments. It requires conversion to open surgery if there is an injury to the great vessels or ureters. On the contrary, the use of robotic system to excise such tumors is easy and safe. The features of the da Vinci Surgical System include seven degrees of freedom, movement instrumentation and 3D vision. These features allow uncomplicated surgery without damage to important structures, which is a challenge in open or laparoscopic surgery.[7] Owing to benefits of the da Vinci Surgical System, the resection of the tumor in this patient was safely achieved and successfully completed.

Choosing to use a robotic-assisted-laparoscopic approach should be determined on an individual basis, with thorough evaluation of the risk: Benefit ratio. Robotic surgery is an already well-established technology being used across the globe; however, the learning curve is long but achievable at specialized centers with a high volume of cases. Further research and clinical studies must be done to explore its advantages.[1]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palep JH. Robotic assisted minimally invasive surgery. J Min Access Surg. 2009;5:1–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.51313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roganovic J. Pelvic ganglioneuroma- case report. Coll Antropol. 2010;34:683–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlig BE, Johnson RL. Presacral tumors and cysts in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:581–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02587141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerullo G, Marrelli D, Rampone B, Miracco C, Caruso S, Di Martino M, et al. Presacral ganglioneuroma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:2129–31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i14.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan I, Wietfeldt DE. Presacral tumors: Diagnosis and management. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:84–93. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1223839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agorastos S, Alex A, Feldman J, Kuncewitch M, Deutsch G, Siskind E, et al. Robotic resection of retro-rectal tumor: An alternative to the Kraske procedure. J Solid Tumors. 2013;3:13–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei TC, Chung HJ, Lin AT, Chen KK. Robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of a retroperitoneal paracaval tumor. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76:724–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]