Abstract

Purpose.

Mutations in the same gene can lead to different clinical phenotypes. In this study, we aim to identify novel genotype–phenotype correlations and novel disease genes by analyzing an unsolved autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa (ARRP) Han Chinese family.

Methods.

Whole exome sequencing was performed for one proband from the consanguineous ARRP family. Stringent variants filtering and prioritizations were applied to identify the causative mutation.

Results.

A homozygous missense variant, c.724G>A; p.V242I, in NEUROD1 was identified as the most likely cause of disease. This allele perfectly segregates in the family and affects an amino acid, which is highly conserved among mammals. A previous study showed that a homozygous null allele in NEUROD1 causes severe syndromic disease with neonatal diabetes, systematic neurological abnormalities, and early-onset retinal dystrophy. Consistent with these results, our patients who are homozygous for a less severe missense allele presented only late-onset retinal degeneration without any syndromic symptoms.

Conclusions.

We identified a potential novel genotype–phenotype correlation between NEUROD1 and nonsyndromic ARRP. Our study supports the idea that NEUROD1 is important for maintenance of the retina function and partial loss-of-function mutation in NEUROD1 is likely a rare cause of nonsyndromic ARRP.

Keywords: retinitis pigmentosa, NEUROD1, genotype–phenotype correlation, next-generation sequencing, retina

We identified a potential novel genotype–phenotype correlation between NEUROD1 and nonsyndromic ARRP.

Introduction

It has been observed that different mutations in the same gene can lead to distinct clinical phenotypes in human patients. This is particularly common for genes that play important roles during multiple developmental stages and/or in different tissues. In these cases, complete loss-of-function (LOF) mutations often cause syndromic phenotypes involving multiple organ systems or showing earlier onset of disease, while partial LOF mutations might lead to a milder phenotype or a subset of the phenotypes caused by complete LOF mutations. For example, human CLN3 plays an important role in lysosome function in brain and retina. Homozygous deletion of a 1.02 kb genomic region, including two coding exons, in CLN3 gene is a major cause of juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, which is characterized by early-onset photoreceptor degeneration, severe neurological impairment, and premature death.1 By contrast, missense mutations in CLN3 can cause late-onset retinal degeneration without any syndromic involvements.2 Uncovering these phenotype-genotype correlations is of clinical importance for molecular diagnosis. Furthermore, a mutation spectrum with corresponding phenotypes can provide structural and functional insights about this gene/protein.

NEUROD1, also known as neurogenic differentiation factor 1, is a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor. Human patients with a homozygous frameshift mutation in NEUROD1 developed early-onset diabetes and neurological abnormalities including retinal dystrophy, suggesting NEUROD1 plays an essential role in early development.3 Neurod1 deficient mice also show severe neonatal diabetes.4 By contrast, the retinal degeneration in Neurod1 knockout mice is relatively late-onset indicating that Neurod1 is also required for adult photoreceptors maintenance.5,6 These findings highlighted the potential diverse function of NEUROD1 in multiple tissues and at different stages.

In this study, we identified a homozygous missense mutation in NEUROD1 associated with nonsyndromic retinitis pigmentosa in a consanguineous family by whole exome sequencing (WES). This finding suggests NEUROD1's essential function in maintaining adult photoreceptors in human and also supports the hypothesis that diverse clinical phenotypes can be caused by mutations in the same gene.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Diagnosis of RP

Written consent was obtained from all participating individuals. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH), and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. Blood samples were obtained from five family members, including two affected siblings, and DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit as instructed by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The proband was identified at the Ophthalmic Genetic Clinic, PUMCH in Beijing, China. Detailed ophthalmic evaluations included best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) tests, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, dilated indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus photography, and visual field tests (Octopus; Interzeag, Schlieren, Switzerland). Optical coherence tomography (OCT; Topcon, Tokyo, Japan) was applied to scan the retina structure. Electroretinography (ERG) with corneal “ERGjet” contact lens electrodes was carried out (RetiPort ERG system; Roland Consult, Wiesbaden, Germany). The ERG protocol complied with the standard published by the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (www.iscev.org, provided in the public domain by the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision).

Library Preparation and WES

The Illumina paired-end DNA library (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) preparation followed the standard manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, DNA was quantified using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). One microgram of total DNA was sheared into fragments of 300 to 500 bp, end-paired, and had a 3′ Adenosine base added. Then Illumina Y-shaped adapters were added to the DNA fragments, and 10 cycles of PCR reactions were applied to amplify the libraries. The library DNA was further quantified using a picogreen assay. Six library DNA samples were pooled together before the capture step. In total 3 μg of pooled DNA was enriched by the NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Hybridization and Wash kit (Nimblegen SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library version 2.0; NimbleGen, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's protocols. After that, the postcapture libraries were quantified using picogreen assay and then sequenced on an Illumina Hiseq2000 machine.

Bioinformatics Analysis

Data were processed using an in-house bioinformatics pipeline as previously described.2,7,8 In particular, raw variants were called using Atlas2 Suite.9 Considering the rareness of RP, variant with a frequency of >0.5% in any of the variant databases queried, including 1000 Genome,10 dbSNP135,11 National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing database,12 National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Exome Sequencing database,13 an internal control database of 11,000 exomes, and an ethnicity-matched control database (approximately 4000 exomes) from Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)14 was filtered out. dbNSFP version 2.3 was used to functionally predict the effects of missense variants.15,16

Validation of Variants by Dideoxy Sequencing

For each identified mutation, a 500-bp flanking sequence at both sides was obtained from the University of California, Santa Cruz, genome browser (hg19 assembly). RepeatMasker was used to mask the repetitive sequence in human genome.17 Primer 3 was used to design a pair of primers for generating a 400 to 600 bp PCR product to sequence the mutation site and at least 50 bp surrounding it.18 After PCR amplification, the amplicons were sequenced on an ABI 3730xl or 3500XL Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Results

Clinical Diagnosis Revealed a Typical Adult-Onset RP Phenotype With No Syndromic Involvements

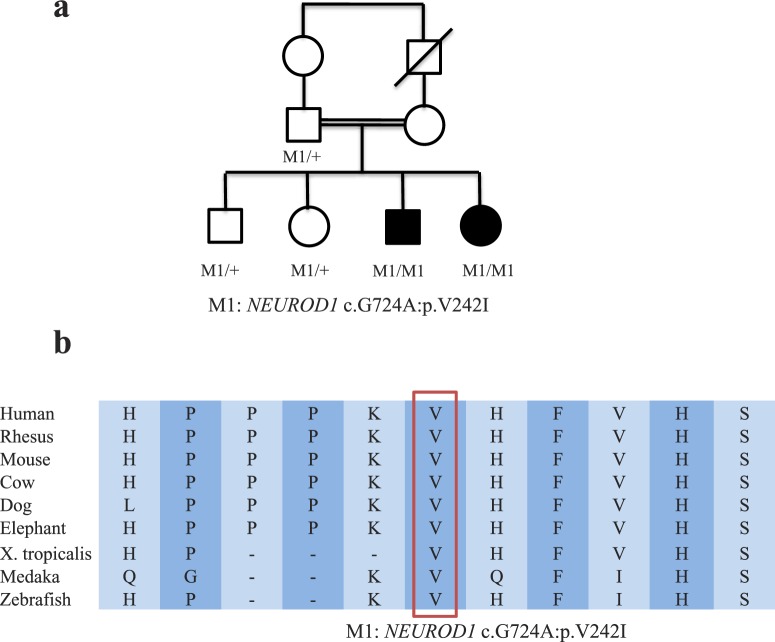

The pedigree is originated from Liaoning province of Northern China. All the family members are Han Chinese. The pedigree shows a typical autosomal recessive inheritance pattern with third-degree consanguinity (first-cousins; Fig. 1a). The proband was a 33-year-old male complaining about night blindness for 15 years and exhibited a progressive decline in visual acuity for 8 years. His BCVA was 0.6 (Snellen decimal chart) for both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed no obvious abnormalities of the anterior segment. His fundus showed bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery region with attenuated retinal vessels (Figs. 2a, 2b). Optical coherence tomography illustrated increased retinal thickness in the macular region with discontinuous inner segments/outer segments junction signal, and loss of foveal pit (Figs. 2e, 2f). Visual field test showed symmetrically loss of upper and temporal visual field with conserved central visual field in both eyes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Electroretinography displayed significantly reduced amplitudes and prolonged implicit time for both rod and cone reactions, which reflected widespread rod and cone degeneration (Supplementary Fig. S2). The proband's affected elder sister was 40 years old and suffered night blindness since childhood. Her BCVA was 0.1/0.15 (right/left). The slit-lamp examination revealed severe subcapsular cataract in both eyes. Diffused retinal pigment epithelial and choroidal atrophy with characteristic bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery was recorded (Figs. 2c, 2d). Vitreous membrane was observed in her right eye. No clear OCT image was obtained due to her cataract. No systemic abnormality was found for both patients. All of the ophthalmic and neurological clinical data was taken at ages 33 and 40, respectively. Detailed clinical phenotypes of the two affected members are listed in the Table.

Figure 1.

(a) Pedigree of the consanguineous ARRP family. The V242I mutation in NEUROD1 segregates perfectly among the family. (b) Multispecies alignment around the amino acid affected by the V242I mutation in NEUROD1. The affected amino acid is highly conserved among mammals.

Figure 2.

Fundus photograph and OCT of the affected family members. Right (a) and left (b) fundus of the proband. Widespread retinal pigment epithelial and choroidal atrophy with pigments in the inferior periphery fundus was observed. Right (c) and left (d) fundus of the proband's elder sister. Defused retinal pigment epithelial and choroidal atrophy with typical bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery was observed. Vitreous membrane was observed in her right eye. Right (e) and left (f) eye OCT of the proband. Loss of foveal pit with increased retinal thickness in the macular region was observed. The inner segments/outer segments signal was discontinuous.

Table. .

Clinical Features of Patients With NEUROD1 Mutations

|

Proband |

Proband's Affected Sister |

|

| Sex/age | M/33* | F/40* |

| Age of onset | 18 | 10 |

| BCVA, OD/OS | 0.6/0.6 | 0.1/0.15 |

| Anterior segment | NA | Dense subcapsular cataract |

| Fundus | Bone-spicule pigmentation in the mid-periphery | Diffused RPE and choroidal atrophy with bone-spicule pigmentation |

| OCT | Increased retinal thickness in the macular region with discontinuous IS/OS junction | No clear image because of cataract |

| VF | Loss of upper and temporal visual field | NA |

| ERG | Moderately decreased rod and cone responses | Nonrecordable |

| BMI | 20.2 | 18.4 |

| FBG, mmol/L | 5.4 | 5.1 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Neurological abnormality | ||

| Developmental delay | No | No |

| Ataxia | No | No |

| Sensorineural deafness | No | No |

| Seizure | No | No |

VF, visual field; BMI, body mass index; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin.

All of the ophthalmic and neurological clinical data were taken at age 33 and 40, respectively. BMI, FBG, and HbA1c were taken 2 years later.

Whole Exome Sequencing Identified a Homozygous Variant c.724G>A; p.V242I in NEUROD1 as the Top Candidate Disease-Causing Mutation

As a prescreening step, customized capture sequencing of 186 known retinal disease-causing genes was performed for the male proband as described before.2 No clear pathogenic mutations in any known retinal disease genes were identified, suggesting mutations in a novel gene might be the cause of disease. Whole-exome capture sequencing of the male proband was then performed to identify the potential novel disease gene. A total of 56.6 million reads were generated, 97.8% of which were mapped to human reference genome hg19, achieving a mean coverage of 59X across the whole exome. Over 180,000 different variants were initially called by Atlas suite.9 After extensive filtering and annotation to exclude common polymorphisms,2,8 only 549 rare and coding-change variants remained. Among them, 16 were in the homozygous state, and 14 were in compound heterozygous state.

Considering the fact of consanguinity, we first focused on the 16 homozygous variants and performed a series of exclusions and prioritizations based on integrative analysis of various sources of information in order to identify the causative mutation (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table S1). Specifically, four variants on chromosome X were given low priority as the inheritance model is not likely to be X-linked. Two variants were excluded because homozygous LOF variants in the same genes were observed in multiple control samples. Two variants were excluded because previous studies indicated recessive mutations in the same genes did not cause retinal phenotype in humans. Three variants were considered low priority since no retinal phenotype was reported in the knockout mouse model of the respective genes. Examination of human RNA-seq data showed four additional variants occurred in genes with little or no expression in the retina making it unlikely they can cause retinal disease.19 In addition, we also performed the same exclusions and prioritizations for all 14 compound heterozygous variants and found no promising candidates (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3.

Flow chart showing that a series of exclusions and prioritizations based on integrative analysis of various sources of information was performed on 16 homozygous variants.

As a result, a homozygous missense variant (NM_002500: c.724G>A; p.V242I) in NEUROD1 was identified as the top candidate disease-causing mutation. The mutation was never found in any control database with a total of over 20,000 samples (1000 Genome, ESP6500, internal exome sequencing database of 11,000 individuals, 4000 ethnicity-matched control exomes from ExAC).10,12 It affects amino acid, which is highly conserved across mammals (Fig. 2b), and has a mixture of prediction scores ranging from “Damaging” to “Benign” according to different in silico prediction algorithms (Supplementary Table S3). This mutation is validated by direct Sanger sequencing. Furthermore, segregation test of this mutation with RP was performed. Both affected individuals are homozygous for this mutation, while all unaffected family members are either heterozygous for the allele or wild type (Fig. 1a).

Discussion

NEUROD1 is a bHLH transcription factor. It is highly expressed in many tissues including the retina, brain, and pancreas. It binds to E box-containing promoter sequences to serve as a transcription activator, thus specifically regulating gene expression.20,21 NEUROD1 has been shown to play critical roles in multiple biological processes including endocrine cell development, neurogenesis, and glucose homeostasis.22–26

Several reports associate NEUROD1 mutations with human genetic disease, though almost all of these reports have focused on diabetes. Heterozygous LOF mutations in NEUROD1 can cause autosomal dominant type 2 diabetes.27 A number of studies also linked NEUROD1 variants to diabetic cohorts.28–31 Strikingly, a single-family report showed that a homozygous frameshift mutation in NEUROD1 can cause a syndromic phenotype that includes retinal dystrophy, permanent diabetes with onset within the first 2 months of life, and early-onset systematic neurological abnormalities.3 This strongly suggests NEUROD1's essential role in multiple tissues, including retina. Hence, the complex genotype–phenotype correlations of NEUROD1 mutations and its potential diverse roles should not be ignored.

Consistent with the phenotype observed in human patients, Neurod1−/− mice under C57BL/6 background display severe neonatal diabetes and die within 5 days after birth due to defects in β cell differentiation.4 Interestingly, Neurod1−/− mice under 129SvJ background have higher survival rate and mice overcoming early lethality show progressive photoreceptor degeneration, suggesting Neurod1's important function for adult photoreceptor maintenance.5 This hypothesis is further supported by a conditional knockout of Neurod1 in mouse retina. Using a Crx promoter, this study confirmed that Neurod1 is required for long-term photoreceptor maintenance and loss of Neurod1 results in age-related degeneration of both rod and cone photoreceptors.6

In our consanguineous ARRP family, both patients were diagnosed as late-onset RP and did not display any other abnormalities despite a complete clinical exam and thorough testing for diabetes and neurological disorders (Table). One explanation for this milder phenotype is that the missense allele carried by the patient is a partial LOF mutation. Given that the patients do not have developmental defects and any other syndromic features, the mutation might only affect the function critical for maintenance of the adult photoreceptor cell. Consistent with this interpretation, the mutation is not located within the bHLH functional domain, which is critical for the protein's function in early developmental process. Therefore, these results suggest that LOF mutations in NEUROD1 cause severe early-onset syndrome while less-damaging missense mutations cause late-onset nonsyndromic retinal degeneration. In order to strengthen this conclusion, we screened over 300 unsolved RP cases for homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in NEUROD1. Unfortunately, no additional supporting cases were observed. With only one pedigree and no functional data, any conclusions should be tentative. However, given all the genetic and functional evidences we have presented above, we believe that the V242I mutation in NEUROD1 is the probable cause of disease in this consanguineous ARRP family. In addition, as the mechanism for NEUROD1 in photoreceptors maintenance is not well understood, the identification of this retinal-specific disease allele is an ideal research target for further studies on NEUROD1's role in retina's long-term survival.

In conclusion, we report, for the first time, that a missense mutation in NEUROD1 is associated with nonsyndromic RP. It is supported by convincing human genetics evidence, obtained through high-quality next generation sequencing, filtering, and segregation. The results are also consistent with previous reports of a Neurod1 mouse knockout model, which shows that Neurod1 is required for survival of adult photoreceptor cells and loss of Neurod1 causes progressive retinal degeneration.5,6 Inclusion of NEUROD1 in genetic diagnosis panels for patients with nonsyndromic or syndromic retinal degenerative disease will improve the molecular diagnosis and increase our understanding of NEUROD1's role in the retina.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family for participating in the study. We thank the Exome Aggregation Consortium and the groups that provided exome variant data for comparison. A full list of contributing groups can be found at http://exac.broadinstitute.org/about. Next-generation sequencing was conducted at the Functional Genomic Core (FGC) facility at Baylor College of Medicine supported by the National Institutes of Health shared instrument grant 1S10RR026550 (to RC).

Supported by grants from the Retinal Research Foundation, Foundation Fighting Blindness and the National Eye Institute (R01EY022356, R01EY018571, BR-GE-0613-0618-BCM [RC]). FW is supported by predoctoral fellowship: The Burroughs Wellcome Fund, The Houston Laboratory, and Population Sciences Training Program in Gene Environment Interaction. RS is supported by Foundation Fighting Blindness (CD-CL-0808-0470-PUMCH and CD-CL-0214-0631-PUMCH).

Disclosure: F. Wang, None; H. Li, None; M. Xu, None; H. Li, None; L. Zhao, None; L. Yang, None; J.E. Zaneveld, None; K. Wang, None; Y. Li, None; R. Sui, None; R. Chen, None

References

- 1. The-International-Batten-Disease-Consortium. Isolation of a novel gene underlying Batten disease, CLN3. Cell. 1995; 82: 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang F, Wang H, Tuan HF, et al. Next generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa: identification of a novel genotype-phenotype correlation and clinical refinements. Hum Genet. 2014; 133: 331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rubio-Cabezas O, Minton JA, Kantor I, Williams D, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Homozygous mutations in NEUROD1 are responsible for a novel syndrome of permanent neonatal diabetes and neurological abnormalities. Diabetes. 2010; 59: 2326–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Naya FJ, Huang HP, Qiu Y, et al. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/neuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1997; 11: 2323–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pennesi ME, Cho JH, Yang Z, et al. BETA2/NeuroD1 null mice: a new model for transcription factor-dependent photoreceptor degeneration. J Neurosci. 2003; 23: 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ochocinska MJ, Munoz EM, Veleri S, et al. NeuroD1 is required for survival of photoreceptors but not pinealocytes: results from targeted gene deletion studies. J Neurochem. 2012; 123: 44–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koenekoop RK, Wang H, Majewski J, et al. Mutations in NMNAT1 cause Leber congenital amaurosis and identify a new disease pathway for retinal degeneration. Nat Genet. 2012; 44: 1035–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu Q, Wang F, Wang H, et al. Next-generation sequencing-based molecular diagnosis of a Chinese patient cohort with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 4158–4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Challis D, Yu J, Evani US, et al. An integrative variant analysis suite for whole exome next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012; 13: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Genomes Project C. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010; 467: 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP Build 135). Accessed June 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Seattle, WA. Available at: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/. ESP6500SI Accessed June 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Environmental Genome Project. Seattle, WA. Available at: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/niehsExome/. NIEHS95 Accessed June 8, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC). Cambridge, MA. Available at: http://exac.broadinstitute.org. Accessed November 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu X, Jian X. Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum Mutat. 2011; 32: 894–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu X, Jian X. Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v2.0: a database of human non-synonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum Mutat. 2013; 34: E2393–E 2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smit A, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. Available at: http://www.repeatmasker.org 1996–2010. Accessed June 27, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol Biol. 2000; 132: 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Farkas MH, Grant GR, White JA, Sousa ME, Consugar MB, Pierce EA. Transcriptome analyses of the human retina identify unprecedented transcript diversity and 3.5 Mb of novel transcribed sequence via significant alternative splicing and novel genes. BMC Genomics. 2013; 14: 486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Poulin G, Turgeon B, Drouin J. NeuroD1/beta2 contributes to cell-specific transcription of the proopiomelanocortin gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997; 17: 6673–6682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Breslin MB, Zhu M, Lan MS. NeuroD1/E47 regulates the E-box element of a novel zinc finger transcription factor, IA-1, in developing nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278: 38991–38997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mastracci TL, Anderson KR, Papizan JB, Sussel L. Regulation of Neurod1 contributes to the lineage potential of Neurogenin3+ endocrine precursor cells in the pancreas. PLoS Genet. 2013; 9: e1003278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boutin C, Hardt O, de Chevigny A, et al. NeuroD1 induces terminal neuronal differentiation in olfactory neurogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107: 1201–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evsen L, Sugahara S, Uchikawa M, Kondoh H, Wu DK. Progression of neurogenesis in the inner ear requires inhibition of Sox2 transcription by neurogenin1 and neurod1. J Neurosci. 2013; 33: 3879–3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andrali SS, Qian Q, Ozcan S. Glucose mediates the translocation of NeuroD1 by O-linked glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 2007; 282: 15589–15596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petersen HV, Jensen JN, Stein R, Serup P. Glucose induced MAPK signalling influences NeuroD1-mediated activation and nuclear localization. FEBS Lett. 2002; 528: 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Malecki MT, Jhala US, Antonellis A, et al. Mutations in NEUROD1 are associated with the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet. 1999; 23: 323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kavvoura FK, Ioannidis JP. Ala45Thr polymorphism of the NEUROD1 gene and diabetes susceptibility: a meta-analysis. Hum Genet. 2005; 116: 192–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Oliveira CS, Hauache OM, Vieira JG, et al. The Ala45Thr polymorphism of NEUROD1 is associated with type 1 diabetes in Brazilian women. Diabetes Metab. 2005; 31: 599–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malecki MT, Cyganek K, Klupa T, Sieradzki J. The Ala45Thr polymorphism of BETA2/NeuroD1 gene and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Polish population. Acta Diabetol. 2003; 40: 109–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu L, Furuta H, Minami A, et al. A novel mutation, Ser159Pro in the NeuroD1/BETA2 gene contributes to the development of diabetes in a Chinese potential MODY family. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007; 303: 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]