Abstract

Background

The horse (Equus ferus caballus) is one of the earliest domesticated species and has played an important role in the development of human societies over the past 5,000 years. In this study, we characterized the genome of the Marwari horse, a rare breed with unique phenotypic characteristics, including inwardly turned ear tips. It is thought to have originated from the crossbreeding of local Indian ponies with Arabian horses beginning in the 12th century.

Results

We generated 101 Gb (~30 × coverage) of whole genome sequences from a Marwari horse using the Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer. The sequences were mapped to the horse reference genome at a mapping rate of ~98% and with ~95% of the genome having at least 10 × coverage. A total of 5.9 million single nucleotide variations, 0.6 million small insertions or deletions, and 2,569 copy number variation blocks were identified. We confirmed a strong Arabian and Mongolian component in the Marwari genome. Novel variants from the Marwari sequences were annotated, and were found to be enriched in olfactory functions. Additionally, we suggest a potential functional genetic variant in the TSHZ1 gene (p.Ala344>Val) associated with the inward-turning ear tip shape of the Marwari horses.

Conclusions

Here, we present an analysis of the Marwari horse genome. This is the first genomic data for an Asian breed, and is an invaluable resource for future studies of genetic variation associated with phenotypes and diseases in horses.

Keywords: Marwari, Horse, Equus ferus caballus, Whole-genome sequencing, Genome

Background

The horse (Equus ferus caballus) was one of the earliest domesticated species and has played numerous important roles in human societies: acting as a source of food, a means of transport, for draught and agricultural work, and for sport, hunting, and warfare [1]. Horse domestication is believed to have started in the western Asian steppes approximately 5,500 years ago, and quickly spread across the Eurasian continent, with herds being augmented by the recruitment of local wild horses [2]. Domestication in the Iberian Peninsula might have represented an additional independent episode, involving horses that survived in a steppe refuge following the reforestation of Central Europe during the Holocene [3].

The horse reference genome has provided fundamental genomic information on the equine lineage and has been used for improving the health and performance of horses [1,4]. Horses exhibit 214 genetic traits and/or diseases that are similar to those of humans [5]. To date, several horse whole genomes have been sequenced and analyzed [4,6]. In 2012, the first whole genome re-sequencing analysis was conducted on the Quarter Horse breed to identify novel genetic variants [4]. In 2013, divergence times among horse fossils, donkey, Przewalski's horse, and several domestic horses were estimated, together with their demographic history [6]. However, currently available whole genome sequences of modern horses only comprise western Eurasian breeds.

Over the centuries, more than 400 distinct horse breeds have been established by genetic selection for a wide number of desired phenotypic traits [7]. The Marwari (also known as Malani) horse is a rare breed from the Marwar region of India, and is one of six distinct horse breeds of India. They are believed to be descended from native Indian ponies, which were crossed with Arabian horses beginning around the 12th century, possibly with some Mongolian influence [8-10]. The Marwari horses were trained to perform complex prancing and leaping movements for ceremonial purposes [11,12]. The Marwari population in India deteriorated in the early 1900s due to improper management of the breeding stock, and only a few thousand purebred Marwari horses remain [12].

Here, we report the first whole genome sequence of a male Marwari horse as one of the Asian breeds and characterize its genetic variations, including single nucleotide variations (SNVs), small insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs). To investigate relationships among different horse breeds, we carried out a genome-wide comparative analysis using previously reported whole genome sequences of six western Eurasian breeds [4,6], and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data of 729 horses from 32 worldwide breeds [13]. Our results provide insights into its genetic background and origin, and identify genotypes associated with the Marwari-specific phenotypes.

Results and discussion

Whole genome sequencing and variation detection

Genomic DNA was obtained from a blood sample of a male Marwari horse (17 years old) and was sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer. A total of 112 Gb of paired-end sequence data were produced with a read length of 100 bp and insert sizes of 456 and 462 bp from two genomic libraries (Additional file 2: Figure S1, Figure S2). A total of 1,013,642,417 reads remained after filtering, and 993,802,097 reads were mapped to the horse reference genome (EquCab2.0 from the Ensembl database) with a mapping rate of 98.04%. (Additional file 2: Figure S3, Figure S4). A total of 133,091,136 reads were identified as duplicates and were removed from further analyses (Additional file 1: Table S1). To enhance the mapping quality, we applied the IndelRealigner algorithm to the de-duplicated reads. A total of 44,835,563 (5.2%) reads were realigned, and the average mapping quality increased from 53.11 to 53.16 (from 29.33 to 43.32 in the realigned reads). The whole genome sequences covered 95.6% of the reference genome at 10 × or greater depth.

To identify novel genomic sequences, we performed a de novo assembly using the unmapped reads (1.8 Gb) to the horse reference genome. A total of 120,159 contigs (24,781,670 bases in length and 227 bp of contig N50 size) were assembled. After mapping the contigs to the reference genome, we found that 25,614 contigs (4,855,119 bases in length and 196 bp of contig N50 size) did not match the reference sequences; indicating that they may be novel regions specific to the Marwari horse breed (Additional file 1: Table S2). To identify the biological functions of these novel regions, the un-matched contigs were further analyzed by BLAST searches using the NCBI protein database. However, none of the contigs significantly matched the known protein database (Additional file 2: Figure S5).

Comparing the Marwari sequence to the reference genome, approximately 5.9 million SNVs and 0.6 million indels were identified (Table 1). Estimates of SNP rate and heterozygosity of the Marwari were similar to those of other horse breeds (Arabian, Icelandic, Norwegian Fjord, Quarter, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred) (Additional file 1: Table S3). We assessed the mutational frequency at the single nucleotide level in the Marwari and compared it to estimates from other breeds (Additional file 1 Table S4). Interestingly, we found that the prevalent mutation types were not consistent among horse breeds. The mutation spectrum of the Marwari was dominated by C>T (G>A) transitions; a pattern which was also observed in the Icelandic, Norwegian Fjord, and Quarter horses. Conversely, the genomes of the Arabian, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred horses were dominated by A>G (T>C) transitions. A significant association between the mutation spectrum and horse breed (p-value < 0.001) was found when we applied a chi-square test using SPSS [14] to statistically compare the differences in the mutation spectrums among the breeds.

Table 1.

Variants in the Marwari horse genome.

| Description | SNVs | Indels | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homozygous | Heterozygous | Novel | Homozygous | Heterozygous | Novel | |

| Total | 2,383,702 | 3,539,864 | 1,577,725 | 343,789 | 234,266 | 249,609 |

| INTERGENIC | 1,565,078 | 2,352,370 | 1,060,195 | 215,679 | 153,412 | 164,564 |

| INTRAGENIC | 3,474 | 5,134 | 1,919 | 556 | 332 | 329 |

| UPSTREAM | 113,184 | 168,184 | 74,923 | 18,300 | 10,582 | 11,178 |

| DOWNSTREAM | 111,918 | 166,365 | 75,592 | 17,866 | 11,504 | 12,203 |

| UTR_5_PRIME | 600 | 684 | 279 | 171 | 27 | 25 |

| UTR_3_PRIME | 1,188 | 1,660 | 802 | 264 | 129 | 149 |

| INTRON | 569,725 | 817,541 | 351,960 | 89,394 | 57,856 | 60,614 |

| Noncoding exon variant | 3,259 | 4,368 | 3,433 | 280 | 198 | 244 |

| Synonymous mutation | 8,053 | 12,586 | 4,209 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nonsynonymous mutation | 7,223 | 10,972 | 4,413 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indels in coding region | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,279 | 226 | 303 |

The Marwari genome consisted of 2,383,702 (40.2%) homozygous and 3,539,864 (59.8%) heterozygous SNVs (Table 1). Among them, 18,195 were found to be nonsynonymous SNVs (nsSNVs). When the Marwari variants were compared to those previously reported from the genomes of other breeds [4,6] and the horse SNP database from the Broad Institute, 1,577,725 SNVs and 249,609 indels were novel variants. Of these, 4,716 variants (4,413 nsSNVs and 303 indels in coding regions) represented amino acid changes which were found in 2,770 genes (2,584 genes with nsSNVs, 279 genes with indels in coding regions, and 93 genes with nsSNVs and indels in coding regions simultaneously). To annotate the variants using well-known functional databases, human orthologs were retrieved from the Ensembl BioMart utility. A total of 1,970 of the 2,770 genes had human orthologs, and 1,896 genes were annotated using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resource 6.7 [15]. The genes with nsSNVs and/or indels in coding regions were highly enriched in olfactory functions (Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6).

Copy number variations (CNVs) were identified using the R library "ReadDepth package" [16]. A total of 2,579 CNVs, including 869 gain and 1,710 loss blocks, were identified in the Marwari genome. The sizes ranged from 3 Kb to 6.43 Mb with an average length of 56 Kb. The CNV region (140 Mb in length) contained 2,504 genes which were duplicated (1,138 genes) or deleted (1,366 genes) (Additional file 1: Table S7). From the functional enrichment analysis, we found that the duplicated genes were enriched in olfactory function, whereas the deleted genes were enriched in immune regulation and metabolic processes (Additional file 1:Table S8, Table S9, Table S10, and Table S11).

Relatedness to other horse breeds

We constructed a phylogenetic tree using SNVs found in the whole genome data of the seven horse breeds (Arabian, Icelandic, Marwari, Norwegian Fjord, Quarter, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred) [4,6]. We identified 11,377,736 nucleotide positions that were commonly found in the seven horse genomes. A total of 25,854 nucleotide positions were used for phylogenetic analysis after filtering for minor allele frequency (MAF), genotyping rate, and linkage disequilibrium (LD). We found that the Marwari horse is most closely related to the Arabian breed (Additional file 2: Figure S6), while the Icelandic horse and Norwegian Fjord were the most distinct from the other breeds, all of which are known to descend from Arabian horses [17,18].

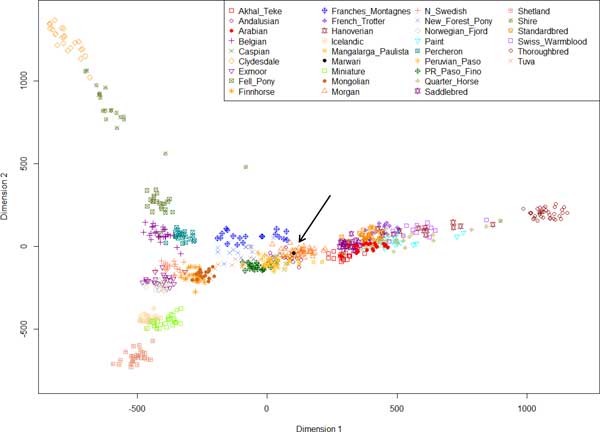

To further explore the relationships among breeds, we compared the Marwari horse genome data with SNP array data from 729 individual horses belonging to 32 domestic breeds [13]. A total of 54,330 nucleotide positions were shared across all individuals including the Marwari horse. After pruning as described above, 10,554 nucleotide positions were used for the comparative analyses. We calculated pairwise genetic distances and conducted multidimensional scaling (MDS) to visualize the relationships among the horse breeds (Figure 1). The Marwari horse fell together with Iberian-lineage breeds, such as the Andalusian, Mangalarga Paulista, Peruvian Paso, and Morgan horse breeds, all of which are known to have an Arabian ancestry [19-22]. Additionally, we found that the Marwari horse fell between Arabian and Mongolian horses, indicating their dual genetic influences on the Marwari horse as previously suggested [8-10].

Figure 1.

Multidimensional scaling plot derived from a Marwari horse and other horse breeds. Black arrow indicates the Marwari horse.

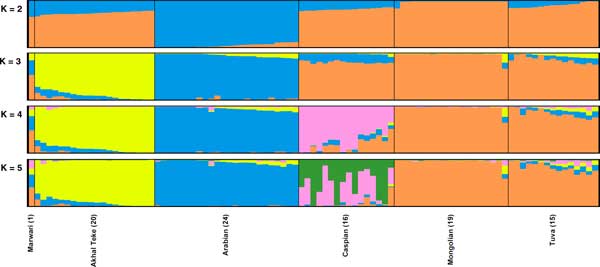

We applied the STRUCTURE program [23,24] to estimate the genetic composition of the Asian horse breeds including the Marwari horse. For K = 2 groups, the Arabian horses were strongly separated from Mongolian horses, and the genetic composition of the Marwari horse was composed of alleles clustering with both the Mongolian horse (65.8%) and the Arabian horse (34.2%) (Figure 2). Other Asian breeds (Akhal Teke, Caspian, and Tuva) also showed genetic admixture between Arabian and Mongolian horses. From K = 3 to K = 5, the Marwari had high genetic components of both Arabian and Mongolian horses, whereas Akhal Teke and Caspian horses were mostly assigned to other clusters. These results indicate that the Marwari is genetically closely related to the Arabian and Mongolian horses. It is unclear whether the latter relationship represents direct genetic input from Mongolian horses or whether these horses are the closest population to the Indian ponies from which the Marwari is thought to have descended [8-10]. Further analysis including Indian ponies and Marwari horses will be required to distinguish the relative importance of these two scenarios, which are not mutually exclusive.

Figure 2.

STRUCTURE analysis using Marwari and Asian horse breeds. For all K values, the Marwari has genetic affinities to both Arabian (blue) and Mongolian horses (orange).

Phenotype association of the identified variants

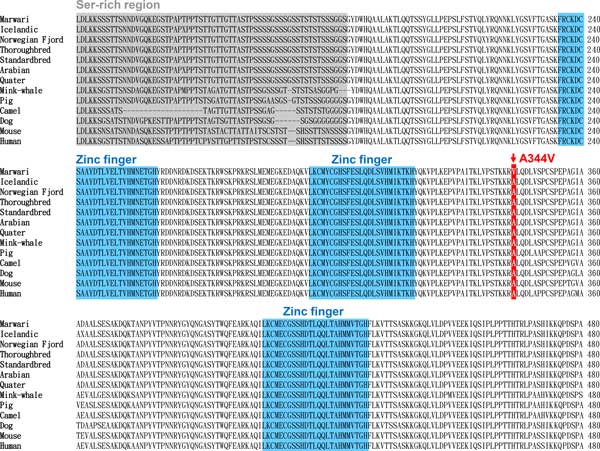

To provide insight into the unique Marwari phenotypes, we investigated amino acid changes specific to this breed compared to those of other breeds (Arabian, Icelandic, Norwegian Fjord, Quarter, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred). A total of 343 amino acid changes in 236 genes were unique to the Marwari horse. Among the 236 genes, 75 genes included one or more amino acid changes predicted by the PolyPhen2 program to alter protein function [25] (Additional file 1: Table S12). Interestingly, the teashirt zinc finger family member 1 (TSHZ1) gene had a homozygous p.Ala344>Val variant (Figure 3). TSHZ1 is involved in transcriptional regulation of developmental processes and is associated with congenital aural atresia in humans, a malformation of the ear occurring in approximately 1 in 10,000 births [26,27]. Additionally, TSHZ1-deficient mice show malformations in the middle ear components [28]. Therefore, the A334V amino acid change in TSHZ1 is a strong candidate as the genetic factor responsible for the inward-turning ear tips characteristic of the Marwari breed. A future genomic comparison with the Kathiawari horse, which also has inward-turning ear tips, might support to this prediction.

Figure 3.

Partial alignment of TSHZ1 amino acid sequences among horse breeds and vertebrate species. Red rectangle indicates a Marwari horse-specific amino acid change (A344V). Gray and blue rectangles indicate a Ser-rich region and Zinc fingers, respectively.

After annotating the Marwari variants for their known disease and trait information [26-55] (Table 2), we found that this breed has a homozygous variant for the g.27991841A>G mutation in the SCL26A2 gene, which causes autosomal recessive chondrodysplasia in equine. Other variants were associated with racing endurance in Thoroughbred horses (g.32772871C>T in COX4I1, g.40279726C>T in ACN9), horse size (g.81481065C>T in HMGA2, g.23259732G>A in LASP1), and pattern of locomotion (g.22999655C>A in DMRT3).

Table 2.

Genetic variants for known traits and diseases.

| PMID | CHR | Coordinate | Gene | Phenotype | Associated Genotype | Marwari Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21070277 [29] | 1 | 74,842,283 | ACTN2 | Racing performance | A>G | A/A |

| 20353955 [30] | 1 | 108,249,293 | TRPM1 | Leopard complex spotting and congenital stationary night blindness | C>T | C/C |

| 17498917 [31] | 1 | 128,056,148 | PPIB | Hereditary equine regional dermal asthenia | G>A | G/G |

| 20419149 [32] | 1 | 138,235,715 | MYO5A | Lavender foal syndrome | Del 1 bp | neg |

| 21070277 [29] | 3 | 32,772,871 | COX4I1 | Racing performance | C>T | T/C |

| 8995760 [33] | 3 | 36,259,552 | MC1R | Chestnut coat color | C>T | C/C |

| 11086549 [34] | 3 | 36,259,554 | MC1R | Chestnut coat color | G>A | G/G |

| 16284805 [35] | 3 | 77,735,520 | KIT | Sabino spotting | A>T | A/A |

| 18253033 [36] | 3 | 77,740,163 | KIT | Tobiano spotting pattern | G>A | G/G |

| 22808074 [37], 22615965 [38] |

3 | 105,547,002 | LCORL, NCAPG | Large body size | T>C | T/T |

| 21070277 [29] | 4 | 40,279,726 | ACN9 | Racing performance | C>T | T/T |

| 12230513 [39] | 5 | 20,256,789 | LAMC2 | Junctional epidermolysis bullosa | Ins C | neg |

| 17029645 [40] | 6 | 73,665,304 | PMEL17 | Silver coat color | G>A | G/G |

| 22808074 [37] | 6 | 81,481,065 | HMGA2 | Large body size | C>T | T/T |

| 19016681 [41] | 8 | 45,603,643- 45,610,231 | LAMA3 | Junctional epidermolysis bullosa | Del 6589 | neg |

| 9103416 [42] | 9 | 35,528,429 | DNAPK | Severe combined immunodeficiency | Del 5 bp | neg |

| 22615965 [38] | 9 | 74,795,013 | ZFAT | Wither height | C>T | C/C |

| 22808074 [37] | 9 | 75,550,059 | ZFAT | Large body size | C>T | C/C |

| 15318347 [43] | 10 | 9,554,699 | RYR1 | Malignant hyperthermia | C>G | C/C |

| 21059062 [44] | 10 | 15,884,567 | CKM | Racing performance | G>A | G/G |

| 18358695 [45] | 10 | 18,940,324 | GYS1 | Polysaccharide storage myopathy | C>T | C/C |

| 7623088 [46] | 11 | 15,500,439 | SCN4A | Equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis | C>T | C/C |

| 22808074 [47] | 11 | 23,259,732 | LASP1 | Large body size | G>A | A/A |

| 21070269 [47] | 14 | 3,761,254 | PROP1 | Dwarfism | G>C | G/G |

| 18802473 [48] | 14 | 26,701,092 | SLC36A1 | Champagne dilution | G>C | G/G |

| 17901700 [49] | 14 | 27,991,841 | SCL26A2 | Autosomal recessively inherited chondrodysplasia |

A>G | G/G |

| 9580670 [50] | 17 | 50,624,658 | EDNRB | Lethal white foal syndrome | GA>CT | GA/GA |

| 20932346 [51] | 18 | 66,493,737 | MSTN | Optimum racing performance | T >C | T/T |

| 12605854 [52] | 21 | 30,666,626 | SLC45A2 | Cream coat color | G>A | G/G |

| 21059062 [44] | 22 | 22,684,390 | COX4I2 | Racing performance | C>T | C/C |

| 11353392 [53] | 22 | 25,168,567 | ASIP | Black and bay color | Del 11 bp | Neg |

| 22932389 [54] | 23 | 22,999,655 | DMRT3 | Pattern of locomotion (altered gait) | C>A | A/C |

| 18641652 [55] | 25 | 6,574,013- 6,581,600 |

STX17 | Gray coat color | Dup 4600 | neg |

Selection in the equid lineage

We assessed the signatures of selection in the equid lineage using the dN/dS (nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site to synonymous substitutions per synonymous site) ratio [56]. A consensus horse (equid) sequence was constructed by integrating all of the available breed genomes (Arabian, Icelandic, Marwari, Norwegian Fjord, Quarter, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred) in an attempt to remove breed specificity and to include an Asian breed component via the central Asian heritage of the Marwari (in contrast to the western Eurasian breeds for which whole genomes had been previously sequenced). A total of 7,711 out of 22,305 genes in the horse reference genome were substituted by the consensus sequences. Using the protein sequences of seven non-horse genomes (camel, pig, cow, minke whale, dog, mouse, and human), 5,459 orthologous gene families were constructed using OrthoMCL [57]. Using alignments of these gene families to estimate dN/dS, we identified 188 genes under selection in the horse genome (Additional file 1: Table S13). The selected genes were particularly enriched in immune response (immune effector process, leukocyte mediated immunity, positive regulation of immune system process, and defense response) and possible motor ability (T-tubule, muscle contraction, and regulation of heart contraction) functions (Additional file 1: Table S14). Over evolutionary time, the horse has developed increased speed and its musculature has become specialized for efficient strides [58,59]. It is therefore possible that the motor activity-associated genes we identified to be under positive selection have contributed to the muscular efficiency seen in modern horses.

Conclusion

Our study provides the first whole genome sequences and analyses of the Marwari, an Asian horse breed. Comparing the Marwari genome to the horse reference genome, approximately 5.9 million SNVs and 0.6 million indels, including 4,716 variants that cause amino acid changes, were identified. We found a clear Arabian and Mongolian component in the Marwari genome, although further work is needed to confirm whether modern Marwari horses also descended from Indian ponies. We analyzed the Marwari variants and found a candidate SNV determining its characteristic inward-turning ear tips. Additionally, we investigated selection in the horse genome through comparisons with other mammalian genomes. By creating a consensus sequence that included information on an Asian breed, we found a number of genetic signatures of selection, providing insights into possible evolutionary and environmental adaptations in the equid lineage. The whole genome sequencing data from the Marwari horse provides a rich and diverse genomic resource that can be used to improve our understanding of animal domestication and will likely be useful in future studies of phenotypes and disease.

Methods

Sample preparation and whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood of a 17 year old male Marwari horse with the XcelGene Blood gDNA Mini Kit (Xcelris Labs Ltd, Gujarat, India) following the manufacturer's protocol. Two genomic libraries with insert sizes of 456 and 462 bp were constructed at Theragen BiO Institute (TBI), TheragenEtex, Korea. The genomic DNA was sheared using Covaris S series (Covaris, MS, USA). The sheared DNA was end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to paired-end adapters, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Truseq DNA Sample Prep Kit v2, Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Adapter-ligated fragments were then size selected on a 2% Agarose gel, and the 520-620 bp band was extracted. Gel extraction and column purification were performed using the MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. The ligated DNA fragments containing adapter sequences were enhanced via PCR using adapter-specific primers. Library quality and concentration were determined using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent, CA, USA). The libraries were quantified using a KAPA library quantification kit (Kapa Biosystems, MA, USA) according to Illumina's library quantification protocol. Based on the qPCR quantification, the libraries were normalized to 2 nM and denatured using 0.1 N NaOH. Cluster amplification of denatured templates was performed in flow cells according to the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina, CA, USA). Flow cells were paired-end sequenced (2 × 100 bp) on an Illumina HiSeq2000 using HiSeq Sequencing kits. A base-calling pipeline (Sequencing Control Software, Illumina) was used to process the raw fluorescent images and the called sequences.

Filtering and mapping processes

Before the mapping step, raw reads were filtered using NGS QC toolkit version 2.3 (cutoff read length for high quality, 70%; cutoff quality score, 20) [60]. After the filtering step, clean reads were mapped to the horse reference genome (Ensembl EquCab2.0, release 72) [1] with BWA version 0.7.5a [61] with minimum seed length (-k 15) and Mark shorter split hits as secondary (-M). We realigned the reads using the GATK [62] IndelRealigner algorithm to enhance the mapping quality, and marked duplicate reads using MarkDuplicates from picard-tools version 1.92 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/).

De novo assembly of unmapped reads

We extracted unmapped sequences from aligned Marwari BAM files. To find Marwari specific genomic regions, we assembled unmapped reads using SOAPdenovo2 [63] with "all" mode and multiple K values (ranged from 23 to 63). A total of 120,159 contigs were obtained, and N50 length was 227bp. To identify whether these contigs are in non-reference regions, we aligned contigs to the horse reference genome. A total of 25,614 contigs were not aligned to the reference genome. The non-reference sequences were further analyzed by BLAST to NCBI protein and DNA sequence databases with the criteria E≤10-5 and identity ≥ 70%.

Variant detection and annotation

Putative variant calls were made using the SAMtools version 0.1.16 [64] mpileup command. In this step, we used the -E option to minimize the noise resulting from pairwise read alignments, and the -A option to use regardless of insert size constraint and/or orientation within pairs. Variants were called using bcftools and then filtered using vcfutils varFilter (minimal depth of 8, maximal depth of 100, Phred scores of SNP call ≥ 30, and no indel present within a 2 bp window) as previously reported [6]. SnpEff [65] was used to annotate the variants. To find unique variants for the Marwari horse, SNVs and small indels were further compared with the horse SNP database that was identified by the Horse Genome Project (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/horse/snp), and other previously reported horse breed genomes [4,6]. Copy number variants based on the differences in sequencing depths were detected using R library "ReadDepth package" with default options. The ReadDepth calculated the thresholds for copy number gain (2.642) and loss (1.380).

Phylogenetic tree construction

Genotype data were extracted from a total of 11,377,736 single nucleotide positions, which were shared and sufficiently covered regions (> 8 × depth), in the seven horse whole genome data (Arabian, Icelandic, Marwari, Norwegian Fjord, Quarter, Standardbred, and Thoroughbred) [4,6]. The genotyping data were merged, and then filtered to remove those SNP with a genotyping rate of < 0.05 and allele frequency > 0.2 using PLINK [66]. SNPs that were in linkage disequilibrium (LD) were also removed: the merged files were pruned for r2 < 0.1 in PLINK, considering 100 SNP windows and moving 25 SNPs per set (-indep-pairwise 100 25). After the filtering and pruning process, 25,854 SNPs remained and were used for the phylogenetic analysis. RAxML version 7.28-ALPHA [67] was used to generate the parsimony starting trees, and RAxML-Light version 1.0.9 [68] was used to carry out tree inference with the GTRGAMMA model of nucleotide substitutions. A total of 100 bootstrap trees were generated for each phylogeny. The resulting tree was drawn by MEGA6 [69].

MDS and population structure analyses

Equine SNP array data of 729 individuals belonging to 32 horse breeds were obtained from a previous report [13]. The Marwari horse data used in this analysis were selected from 54,330 nucleotide positions that were derived from the SNP array data. The SNP array and Marwari data were filtered and pruned to remove SNPs with the same cutoffs described above, except that the MAF option was set to --maf < 0.05. A total of 10,554 single nucleotide positions were used for the following comparative analyses.

The MDS plot was drawn in R [70] using the "MASS" library and "canberra" distance metric. STRUCTURE version 2.3.4 [23,24] was used to cluster Asian breeds based on genetic similarity, investigating K values from 2 to 5. Each run for a given K value consisted of a 15,000 steps burn-in and 35,000 MCMC repetitions. We applied a default admixture model and a default assumption that allele frequencies were correlated. The convergence of STRUCTURE runs was evaluated by the equilibrium of alpha. Individual and population clump files were produced with Structure Harvester [71] and visualized in Distruct1.1 [72].

Orthologous gene family

Protein sequences of cow (Bos taurus), dog (Canis familiaris), human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), and pig (Sus scrofa) were downloaded from the Ensembl database version 72. Protein sequences of minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) [73] and camel (Camelus bactrianus) [74] were obtained from the original publications. A total of eight species were used to identify orthologous gene clusters with OrthoMCL 2.0.9. Pairwise sequence similarities between all protein sequences were calculated using BLASTP with an e-value cutoff of 1E-05. On the basis of the BLASTP results, OrthoMCL was used to perform a Markov clustering algorithm with inflation value (-I) of 1.5. The OrthoMCL was run with an e-value exponent cutoff of -5 and percent match cutoff of 50%. In total, 5,501 orthologous groups were shared by all eight species. The representative sequences for each gene cluster were selected using the longest horse transcript and the corresponding protein sequences of the other species. BLASTP searches (E-value 1E-5 cutoff) between horse and all the other species were used in this process. Finally, we identified 5,459 1:1:1:1:1:1:1:1 orthologs.

Molecular evolutionary analysis

The phylogenetic tree was constructed from 5,459 single copy ortholog genes. CODEML in PAML 4.5 [75] was used to estimate the dN/dS ratio, where dN indicates nonsynonymous substitution rate and dS indicates synonymous substitution rate. The dN/dS ratio along the horse branch (free-ratio molel) and dN/dS ratio for all branches (one-ratio model) were calculated as the branch model. We also applied the branch-site model to further examine potential positive selection [76]. The LRTs (likelihood ratio tests) were applied to assess statistical significance of the branch-site model. We supposed that positively selected genes are that of having a higher dN/dS ratio with the free-ratios model than that with the one-ratio model and having p-value < 0.05 from branch-site model.

Availability of supporting data

Whole genome sequence data was deposited in the SRA database at NCBI with Biosample accession numbers SAMN02767683. SRA of whole genome sequencing can be accessed via reference numbers SRX535352. The data can also be accessed through BioProject accession number PRJNA246445 for the whole genome sequence data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: JB and WKP. Performed the experiments: KMP. Analyzed the data: JHJ, SJho, YSC, HJH, and JL. Study design, subject recruitment, and sample preparation: PG and JB. Data interpretation: JHJ, SJho, YSC, HJH, and JL. Wrote the paper: JHJ, YSC, HMK, HJH, JE, KH, AM, PG, and JB.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

JeHoon Jun, Email: junjh0701@gmail.com.

Yun Sung Cho, Email: joys0406@gmail.com.

Haejin Hu, Email: haejin.hu@gmail.com.

Hak-Min Kim, Email: howmany2@gmail.com.

Sungwoong Jho, Email: sungwoong.jho@gmail.com.

Priyvrat Gadhvi, Email: priyvratgadhvi@gmail.com.

Kyung Mi Park, Email: kyungmi.park@therabio.kr.

Jeongheui Lim, Email: jeongheuilim@gmail.com.

Woon Kee Paek, Email: paekwk@naver.com.

Kyudong Han, Email: kyudong.han@gmail.com.

Andrea Manica, Email: am315@cam.ac.uk.

Jeremy S Edwards, Email: jsedwards@salud.unm.edu.

Jong Bhak, Email: jongbhak@genomics.org.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2008-2004707 and 2013M3A9A5047052), the Industrial Strategic Technology Development Program, 10040231, 'Bioinformatics platform development for next generation bioinformation analysis' funded by the Ministry of Knowledge Economy (MKE, Korea), and the National Science Museum (NMK, Korea). The Equestrian Club of Gujarat and its office-bearer Mr. Virendra Kankariya provided samples of a registered Marwari horse for the study. We also thank Xcelris Genomics, Ahmedabad, India, and Dr Surendra Chikara, Ms. Arpita Ghosh, and the technical team of Xcelris for their work in DNA extraction, library preparation and shipment to GRF, South Korea. Authors thank TheragenEtex for surporting the research by providing GRF with computational and experimental resource for the NGS analyses. Publication costs were supported by the National Science Museum (NMK, Korea).

This article has been published as part of BMC Genomics Volume 15 Supplement 9, 2014: Thirteenth International Conference on Bioinformatics (InCoB2014): Computational Biology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmcgenomics/supplements/15/S9.

References

- Wade CM, Giulotto E, Sigurdsson S, Zoli M, Gnerre S, Imsland F, Lear TL, Adelson DL, Bailey E, Bellone RR, Blocker H, Distl O, Edgar RC, Garber M, Leeb T, Mauceli E, MacLeod JN, Penedo MC, Raison JM, Sharpe T, Vogel J, Andersson L, Antczak DF, Biagi T, Binns MM, Chowdhary BP, Coleman SJ, Della Valle G, Fryc S, Guerin G. et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis, and population genetics of the domestic horse. Science. 2009;326:865–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1178158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmuth V, Eriksson A, Bower MA, Barker G, Barrett E, Hanks BK, Li S, Lomitashvili D, Ochir-Goryaeva M, Sizonov GV, Soyonov V, Manica A. Reconstructing the origin and spread of horse domestication in the Eurasian steppe. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8202–8206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111122109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmuth V, Eriksson A, Bower MA, Cañon J, Cothran G, Distl O, Glowatzki-Mullis ML, Hunt H, Luís C, do Mar Oom M, Yupanqui IT, Ząbek T, Manica A. European Domestic Horses Originated in Two Holocene Refugia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan R, Cohen ND, Sawyer J, Ghaffari N, Johnson CD, Dindot SV. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Genetic Variant Analysis of a Quarter Horse Mare. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Animals. http://omia.angis.org.au/home

- Orlando L, Ginolhac A, Zhang G, Froese D, Albrechtsen A, Stiller M, Schubert M, Cappellini E, Petersen B, Moltke I, Johnson PL, Fumagalli M, Vilstrup JT, Raghavan M, Korneliussen T, Malaspinas AS, Vogt J, Szklarczyk D, Kelstrup CD, Vinther J, Dolocan A, Stenderup J, Velazquez AM, Cahill J, Rasmussen M, Wang X, Min J, Zazula GD, Seguin-Orlando A, Mortensen C. et al. Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. Nature. 2013;499:74–81. doi: 10.1038/nature12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks B. International Encyclopedia of Horse Breeds. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn Hartley Edwards. The Encyclopedia of the Horse. New York: Dorling Kindersley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wendy Doniger. The Hindus: An Alternative History. New Delhi: Penguin Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Behl R, Behl J, Gupta N, Gupta SC. Genetic relationships of five Indian horse breeds using microsatellite markers. Animal. 2007;4:483–488. doi: 10.1017/S1751731107694178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutson Judith. Storey's Illustrated Guide to 96 Horse Breeds of North America. North adams: Storey Publishing; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta AK, Chauhan M, Tandon SN, Sonia. Genetic diversity and bottleneck studies in the Marwari horse breed. J Genet. 2005;84:295–301. doi: 10.1007/BF02715799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JL, Mickelson JR, Rendahl AK, Valberg SJ, Andersson LS, Axelsson J, Bailey E, Bannasch D, Binns MM, Borges AS, Brama P, da Câmara Machado A, Capomaccio S, Cappelli K, Cothran EG, Distl O, Fox-Clipsham L, Graves KT, Guérin G, Haase B, Hasegawa T, Hemmann K, Hill EW, Leeb T, Lindgren G, Lohi H, Lopes MS, McGivney BA, Mikko S, Orr N. et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals selection for important traits in domestic horse breeds. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. NY: IBM; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Zheng X, Yang J, Imamichi T, Stephens R, Lempicki RA. Extracting biological meaning from large gene lists with DAVID. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2009. Chapter 13:Unit 13.11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Miller CA, Hampton O, Coarfa C, Milosavljevic A. ReadDepth: a parallel R package for detecting copy number alterations from short sequencing reads. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John F, Wall. Famous Running Horses: Their Forebears and Descendants. Whitefish: Literary Licensing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robert Moorman Denhardt. The Quarter Horse Running: America's Oldest Breed. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas. This is the Spanish Horse. London: J A Allen & Co Ltd; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Milner. Godolphin Arabian: Story of the Matchem Line. London: J. A. Allen; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Breed of Livestock. http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/horses/

- International Museum of the HORSE. http://www.imh.org/exhibits/online/breeds-of-the-world

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and1 correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164:1567–1587. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTMANN F. Congenital atresia of the ear in man and animals. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1955;64:824–858. doi: 10.1177/000348945506400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellon RF, Branstetter BF 4th. Prospective blinded study of computed tomography in congenital aural atresia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1286–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coré N, Caubit X, Metchat A, Boned A, Djabali M, Fasano L. Tshz1 is required for axial skeleton, soft palate and middle ear development in mice. Dev Biol. 2007;308:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EW, Gu J, McGivney BA, MacHugh DE. Targets of selection in the Thoroughbred genome contain exercise-relevant gene SNPs associated with elite racecourse performance. Anim Genet. 2010;41:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellone RR, Forsyth G, Leeb T, Archer S, Sigurdsson S, Imsland F, Mauceli E, Engensteiner M, Bailey E, Sandmeyer L, Grahn B, Lindblad-Toh K, Wade CM. Fine-mapping and mutation analysis of TRPM1: a candidate gene for leopard complex (LP) spotting and congenital stationary night blindness in horses. Brief Funct Genomics. 2010;9:193–207. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elq002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryon RC, White SD, Bannasch DL. Homozygosity mapping approach identifies a missense mutation in equine cyclophilin B (PPIB) associated with HERDA in the American Quarter Horse. Genomics. 2007;90:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Gabreski N, Miller D, Brisbin A, Brown HE, Streeter C, Mezey J, Cook D, Antczak DF. Whole-genome SNP association in the horse: identification of a deletion in myosin Va responsible for Lavender Foal Syndrome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000909. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund L, Moller MJ, Sandberg K, Andersson L. A missense mutation in the gene for melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor (MC1R) is associated with the chestnut coat color in horses. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:895–899. doi: 10.1007/s003359900264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner HJ, Reissmann M. New polymorphism detected in the horse MC1R gene. Anim Genet. 2000;31:289–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.2000.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Bailey E. Exon skipping in the KIT gene causes a Sabino spotting pattern in horses. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:893–902. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-2472-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SA, Lear TL, Adelson DL, Bailey E. A chromosome inversion near the KIT gene and the Tobiano spotting pattern in horses. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;119:225–230. doi: 10.1159/000112065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makvandi-Nejad S, Hoffman GE, Allen JJ, Chu E, Gu E, Chandler AM, Loredo AI, Bellone RR, Mezey JG, Brooks SA, Sutter NB. Four loci explain 83% of size variation in the horse. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signer-Hasler H, Flury C, Haase B, Burger D, Simianer H, Leeb T, Rieder S. A genome-wide association study reveals loci influencing height and other conformation traits in horses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito F, Charlesworth A, Linder K, Ortonne JP, Baird J, Meneguzzi G. Animal models for skin blistering conditions: absence of laminin 5 causes hereditary junctional mechanobullous disease in the Belgian horse. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:684–691. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunberg E, Andersson L, Cothran G, Sandberg K, Mikko S, Lindgren G. A missense mutation in PMEL17 is associated with the Silver coat color in the horse. BMC Genet. 2006;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves KT, Henney PJ, Ennis RB. Partial deletion of the LAMA3 gene is responsible for hereditary junctional epidermolysis bullosa in the American Saddlebred Horse. Anim Genet. 2009;40:35–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EK, Perryman LE, Meek K. A kinase-negative mutation of DNA-PK(CS) in equine SCID results in defective coding and signal joint formation. J Immunol. 1997;158:3565–3569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman M, Riehl J, Aldridge BM, Lecouteur RA, Stott JL, Pessah IN. Association of a mutation in the ryanodine receptor 1 gene with equine malignant hyperthermia. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:356–365. doi: 10.1002/mus.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, MacHugh DE, McGivney BA, Park SD, Katz LM, Hill EW. Association of sequence variants in CKM (creatine kinase, muscle) and COX4I2 (cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 4, isoform 2) genes with racing performance in Thoroughbred horses. Equine Vet J. 2010;42:569–75. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue ME, Valberg SJ, Miller MB, Wade C, DiMauro S, Akman HO, Mickelson JR. Glycogen synthase (GYS1) mutation causes a novel skeletal muscle glycogenosis. Genomics. 2008;91:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC, Hayward LJ, Beech J, Brown RH Jr. Sodium channel inactivation is impaired in equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1892–1899. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr N, Back W, Gu J, Leegwater P, Govindarajan P, Conroy J, Ducro B, Van Arendonk JA, MacHugh DE, Ennis S, Hill EW, Brama PA. Genome-wide SNP association-based localization of a dwarfism gene in Friesian dwarf horses. Anim Genet. 2010;41:2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Brooks S, Bellone R, Bailey E. Missense mutation in exon 2 of SLC36A1 responsible for champagne dilution in horses. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Knorr C, Hall AJ, Broad TE, Brenig B. Sequence analysis of the equine SLC26A2 gene locus on chromosome 14q15-->q21. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;118:55–62. doi: 10.1159/000106441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang GC, Croaker D, Zhang AL, Manglick P, Cartmill T, Cass D. A dinucleotide mutation in the endothelin-B receptor gene is associated with lethal white foal syndrome (LWFS); a horse variant of Hirschsprung disease. Hum Mol Gene. 1998;7:1047–1052. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EW, McGivney BA, Gu J, Whiston R, Machugh DE. A genome-wide SNP association study confirms a sequence variant (g.66493737C > T) in the equine myostatin (MSTN) gene as the most powerful predictor of optimum racing distance for Thoroughbred racehorses. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:552. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariat D, Taourit S, Guérin G. A mutation in the MATP gene causes the cream coat colour in the horse. Genet Sel Evol. 2003;35:119–133. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-35-1-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder S, Taourit S, Mariat D, Langlois B, Guérin G. Mutations in the agouti (ASIP), the extension (MC1R), and the brown (TYRP1) loci and their association to coat color phenotypes in horses (Equus caballus) Mamm Genome. 2001;12:450–455. doi: 10.1007/s003350020017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson LS, Larhammar M, Memic F, Wootz H, Schwochow D, Rubin CJ, Patra K, Arnason T, Wellbring L, Hjälm G, Imsland F, Petersen JL, McCue ME, Mickelson JR, Cothran G, Ahituv N, Roepstorff L, Mikko S, Vallstedt A, Lindgren G, Andersson L, Kullander K. Mutations in DMRT3 affect locomotion in horses and spinal circuit function in mice. Nature. 2012;488:642–646. doi: 10.1038/nature11399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren Pielberg G, Golovko A, Sundström E, Curik I, Lennartsson J, Seltenhammer MH, Druml T, Binns M, Fitzsimmons C, Lindgren G, Sandberg K, Baumung R, Vetterlein M, Strömberg S, Grabherr M, Wade C, Lindblad-Toh K, Pontén F, Heldin CH, Sölkner J, Andersson L. A cis-acting regulatory mutation causes premature hair graying and susceptibility to melanoma in the horse. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1004–1009. doi: 10.1038/ng.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen R, Bustamante C, Clark AG, Glanowski S, Sackton TB, Hubisz MJ, Fledel-Alon A, Tanenbaum DM, Civello D, White TJ, J Sninsky J, Adams MD, Cargill M. A scan for positively selected genes in the genomes of humans and chimpanzees. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:el70. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfadden BJ. Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Macfadden BJ. Evolution. Fossil horses--evidence for evolution. Science. 2005;307:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.1105458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RK, Jain M. NGS QC Toolkit: A Toolkit for Quality Control of Next Generation Sequencing Data. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo R, Liu B, Xie Y, Li Z, Huang W, Yuan J, He G, Chen Y, Pan Q, Liu Y, Tang J, Wu G, Zhang H, Shi Y, Liu Y, Yu C, Wang B, Lu Y, Han C, Cheung DW, Yiu SM, Peng S, Xiaoqian Z, Liu G, Liao X, Li Y, Yang H, Wang J, Lam TW, Wang J. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience. 2012;1:18. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence alignment/map (SAM) format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly(Austin) 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Amer J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Aberer AJ, Goll C, Smith SA, Berger SA, Izquierdo-Carrasco F. RAxML-Light: a tool for computing terabyte phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2064–2066. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A Language for Data Analysis and Graphics. J Comput Graph Stat. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Earl DA, Vonholdt BM. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour. 2012;4:359–361. doi: 10.1007/s12686-011-9548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg NA. DISTRUCT: a program for the graphical display of population structure. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yim HS, Cho YS, Guang X, Kang SG, Jeong JY, Cha SS, Oh HM, Lee JH, Yang EC, Kwon KK, Kim YJ, Kim TW, Kim W, Jeon JH, Kim SJ, Choi DH, Jho S, Kim HM, Ko J, Kim H, Shin YA, Jung HJ, Zheng Y, Wang Z, Chen Y, Chen M, Jiang A, Li E, Zhang S, Hou H. et al. Minke whale genome and aquatic adaptation in cetaceans. Nat Genet. 2014;46:88–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji R, Cui P, Ding F, Geng J, Gao H, Zhang H, Yu J, Hu S, Meng H. Monophyletic origin of domestic bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus bactrianus ferus) Anim Genet. 2009;40:377–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2008.01848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nielsen R, Yang Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.