Abstract

The effective management of women with human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive, cytology-negative results is critical to the introduction of HPV testing into cervical screening. HPV typing has been recommended for colposcopy triage, but it is not clear which combinations of high-risk HPV types provide clinically useful information. This study included 18,810 women with Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2)-positive, cytology-negative results and who were age ≥30 years from Kaiser Permanente Northern California. The median follow-up was 475 days (interquartile range [IQR], 0 to 1,077 days; maximum, 2,217 days). The baseline specimens from 482 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or cancer (CIN3+) and 3,517 random HC2-positive noncases were genotyped using 2 PCR-based methods. Using the case-control sampling fractions, the 3-year cumulative risks of CIN3+ were calculated for each individual high-risk HPV type. The 3-year cumulative risk of CIN3+ among all women with HC2-positive, cytology-negative results was 4.6%. HPV16 status conferred the greatest type-specific risk stratification; women with HC2-positive/HPV16-positive results had a 10.6% risk of CIN3+, while women with HC-2 positive/HPV16-negative results had a much lower risk of 2.4%. The next most informative HPV types and their risks in HPV-positive women were HPV33 (5.9%) and HPV18 (5.9%). With regard to the etiologic fraction, 20 of 71 cases of cervical adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and adenocarcinoma in the cohort were positive for HPV18. HPV16 genotyping provides risk stratification useful for guiding clinical management; the risk among HPV16-positive women clearly exceeds the U.S. consensus risk threshold for immediate colposcopy referral. HPV18 is of particular interest because of its association with difficult-to-detect glandular lesions. There is a less clear clinical value of distinguishing the other high-risk HPV types.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with a group of high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPV) has been identified as the cause of cervical cancer; thus, high-risk HPV testing is being incorporated into cervical cancer screening to improve cervical cancer prevention. Recently released U.S. guidelines recommend cotesting with HPV assays and cytology (1) as an alternative to the use of cytology alone. Moreover, primary stand-alone HPV testing is being introduced in multiple regions (2), including the United States (3). As a major advantage, HPV testing is more sensitive than cytology alone, and a negative HPV test result provides prolonged reassurance against cervical cancer, permitting the safe lengthening of screening intervals (4, 5).

As a disadvantage, HPV testing is less specific than cytology, and optimal management is unclear for some of the nonnormal cytology/HPV combined results that occur with HPV testing, whether in the context of cotesting or primary HPV testing followed by cytology triage of HPV-positive women (6, 7). One prominent issue, that of HPV-positive/cytology-negative results, i.e., the finding of positive HPV test results when cytology result is negative, is common in absolute terms. For example, HPV-positive/cytology-negative results were found in nearly 4% of the cotest results in a recent large series of approximately 1 million women age 30 to 64 years at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) (8, 9).

The decision of how to manage HPV-positive/cytology-negative results is not straightforward. Recently, U.S. consensus guideline groups have issued recommended management strategies based on comparisons of the risks of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN3) or cancer (CIN3+, including adenocarcinoma in situ). These consensus guidelines form the basis for the consistent management of women with similar risks. Specifically, for women with HPV-positive/cytology-negative results, the attendant risk is not quite high enough for immediate colposcopy (1, 10). In comparison, immediate colposcopy is recommended for cytologically evident HPV infection (HPV-positive atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASC-US] or low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion [LSIL]) (10). Cytologically evident HPV infection confers a 5-year risk of CIN3+ that is only slightly higher than that for HPV-positive/cytology-negative results. However, referring all women with HPV-positive/cytology-negative results would more than double the number of colposcopic procedures, and many of those women would not yet have colposcopically diagnosable lesions (8).

Thus, the guidelines recommend managing HPV-positive/cytology-negative results by return testing at 1 year (1, 8). As an alternative to repeat cotesting in 1 year, HPV genotyping for HPV16 and HPV18 is also recommended. If the HPV-positive/cytology-negative result is linked to HPV16 or HPV18, immediate colposcopy is recommended instead of a 1-year return.

Genotyping for HPV16 and HPV18 is supported by long-term observational studies that have shown an elevated risk particularly for HPV16 compared with that for the other high-risk HPV types (11–13, 23). The rationale for separating out the second most important carcinogenic type, HPV18, is less certain; in part, it is related to the association of HPV18 with cervical adenocarcinoma, which is not well-detected by cytology (11). The need to distinguish additional HPV types is even less clear.

The present analysis examined which individual types of HPV provide useful risk stratification in the management of HPV-positive/cytology-negative results. The study was nested in a large cohort of HPV-positive women being followed at KPNC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

This study is based on data from women in the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-KPNC Persistence and Progression (PaP) cohort who had a positive HPV test result (Hybrid Capture 2 [HC2], Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) between 2007 and 2011. KPNC introduced HPV cytology cotesting into routine practice in 2003 for cervical cancer screening at 3-year intervals among women age ≥30 (11, 14). Starting in 2007, the PaP cohort was created by collecting residual cervical specimens in specimen transport medium (STM) (Qiagen) from a majority of women who tested positive with the Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2) (e.g., it was not possible to process specimens testing positive on Friday afternoons), as well as a random sample of HPV-negative specimens (which were not considered in the present study). After the specimens were used for HC2 testing for clinical purposes, the residual specimens were neutralized and archived, as described below (15).

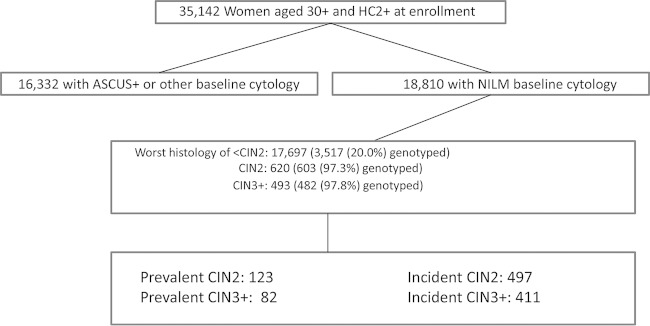

From 2007 to 2011, specimens and data were collected from >55,000 women, including 35,000 women with HC2-positive results who were age ≥30 years (Fig. 1) who agreed to participate via a mailed opt-out letter; 7% of women opted out. The NCI and KPNC institutional review boards approved the study yearly. The present study focuses on the HPV typing of cases and controls (see below) from the subcohort of approximately 18,000 women aged ≥30 years with a baseline HPV-positive, cytology-negative result.

FIG 1.

Study population. The study population included 18,810 women aged ≥30 years with negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) baseline cytology and HC2 positivity. Virtually all women with CIN2 and CIN3+ were genotyped, along with a 20% random sample of control women with <CIN2. The prevalent cases and controls were genotyped in the Burk lab, while the incident cases and controls were genotyped by Roche Molecular Systems. The genotyping that was performed permitted an estimation of 3-year rates of CIN3+ and CIN2 by type. The median follow-up times in days for the case and control groups, from enrollment testing to diagnosis for cases and last screen for controls, were: prevalent CIN2, 69 days; prevalent CIN3+, 82 days; incident CIN2, 503 days; incident CIN3+, 526 days; and controls, 916 days. By the last visit, 72.2% of the controls were HC2 negative.

Pap tests were performed at KPNC regional and facility laboratories; HPV testing of a cocollected second cervical specimen was performed at a single regional laboratory. Until 2009, conventional Pap slides were manually reviewed following processing by the BD FocalPoint slide profiler (BD Diagnostics, Burlington, NC, USA), in accordance with FDA-approved protocols. Starting in 2009, KPNC transitioned to liquid-based cytology using BD SurePath (BD Diagnostics). Conventional or liquid-based Pap tests were reported according to the 2001 Bethesda system. HC2 was used to test for a pool of high-risk HPV types, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

For the present study, baseline PaP cohort specimens from 4,602 women with HC2-positive, cytology-negative results who were age ≥30 years were genotyped retrospectively for research purposes in 2 non-KPNC laboratories. The typing of informative enrollment specimens was performed as a nested case-control study, as described below. Follow-up data on subsequent cytology and histology from the study cases and controls were obtained; all personal identifiers were removed prior to doing the analyses.

Processing of HC2-positive specimens.

The specimens in STM were neutralized within 14 h to minimize DNA damage that might occur with extended storage under alkaline conditions. Specifically, a 0.5× volume of neutralization buffer (180 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid and 100 mM acetic acid; part no. RR11093.01; HyClone) was added to the denatured samples. The exact amount of buffer depended on the residual volume after HC2 testing. The sample was mixed using a vortex mixer, and the solution was examined for color to determine adequate neutralization (indicator turns yellow when neutral).

Definitions of cases and controls.

We focused on CIN3+ as the main case group but also included CIN2+, despite a lack of diagnostic reproducibility (16), because CIN2 is commonly treated. Cases that were diagnosed directly following enrollment testing without an intervening second screen were considered prevalent. A random sample of HC2-positive women who had not been diagnosed as CIN2+ were chosen as prevalent controls, and all were typed by the laboratory of Robert Burk at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in an extension of a previously reported prevalent case-control analysis (15). Cases that were diagnosed subsequent to enrollment (after a second screen) were considered incident and typed by Roche Molecular Systems at their research laboratory in Pleasanton, CA. To compare these with the incident cases, a random sample of HPV-positive women who had not been diagnosed with CIN2+ and had returned at least for one subsequent screening at approximately 1 year postenrollment were typed by Roche Molecular Systems (17). All laboratory testing was masked to clinical outcomes.

HPV typing of prevalent cases and controls.

The MY09/M11 L1 degenerate primer PCR (MY09/11 PCR) system used by the Burk laboratory to test prevalent cases and controls has been described (15, 18). Dot blot hybridization of the amplicons using HPV genotype-specific oligonucleotide probes was used to identify >20 individual HPV genotypes, but this analysis focused on the high-risk HPV types targeted by HC2 (HPV16, HPV18, HPV31, HPV33, HPV35, HPV39, HPV45, HPV51, HPV52, HPV56, HPV58, HPV59, and HPV68) and HPV66, which is commonly detected by cross-reactivity. The specimens that tested positive for HPV on PCR but had no HPV genotype detected by dot blot hybridization were retested and/or subjected to sequencing to maximize HPV genotype detection.

HPV typing of incident cases and controls.

The incident cases and controls were typed by Roche Molecular Systems collaborators using a Linear Array (LA) assay (Amplicor Linear Array HPV assay; Roche Molecular Systems), as previously described (17). In brief, automated sample extraction was performed on the neutralized STM sample using the ×480 sample extraction module of the cobas 4800 system. The HPV LA test was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions for use, with the following exceptions: (i) a 50-μl portion of extracted sample from the ×480 module of the cobas 4800 system was used as a target in the PCR. If the extracted samples had to be stored before amplification, they were sealed tightly with foil film (part no. 2923–0100; USA Scientific TempPlate sealing foil) and stored at 4°C until use (never frozen). (ii) Ten microliters of a 1 M Tris-HCl solution containing 0.09% sodium azide (pH 7.4) was added per tube of activated LA assay master mix to compensate for the alkaline pH of the cobas extract, which was not optimized for use with the LA assay. To facilitate higher-throughput testing of 94 specimens per run, 8 tubes of activated master mix were pooled, to which 80 μl of Tris buffer was added. This pooled LA assay master mix was then mixed by inverting it a minimum of five times before dispensing into the reaction tubes. The amplified samples were hybridized to the HPV LA assay oligonucleotide probe strip and scored as per the manufacturer's recommendations.

In addition, to reduce the chance of user read error, a research software program, HPV StripScan, was utilized to confirm the HPV LA assay genotypes. The Roche StripScan is internal research software used to acquire and process images of strips using an office type scanner. The software measures the intensities of the probe regions on the strips and makes initial probe call determinations that are reviewed and accepted by expert users. In the event of a discrepancy between the manual read and the StripScan result, a second blinded manual read was performed of the 48-strip run; the consensus result (2 out of 3) was reported.

Of note, the LA assay detects HPV52 only as part of a pooled probe. We classified a specimen as HPV52 positive only if the grouped probe was positive but no other types in the pool (which are detected individually as well) were positive.

Comparison of 2 typing assays.

A total of 137 HC2-positive enrollment specimens from the control subjects were typed by both laboratories, permitting a masked interassay comparison of detection of the 14 HPV types targeted by the study. Because some individual HPV types were uncommon, we combined the individual typing agreement across all types. With this pooling, agreement, as measured by the kappa statistic, was shown to be very good (kappa = 0.79); however, the HPV LA assay detected significantly more types than did the MY09-MY11 PCR assay (P < 0.001 by asymmetry chi-square). Due to the imperfect agreement between the two HPV assays, the pooled case-control analysis was confirmed by separate analyses for the incident and prevalent cases.

Statistical analyses.

The frequency and percentage of each high-risk type of HPV for each of the diagnostic categories (CIN3+ cases, CIN2 cases, and <CIN2 controls) were tabulated. The women who were infected with more than one HPV type were counted more than once for each positive type in this tabulation.

The main purpose of the statistical analysis was to determine whether detecting the presence of a particular type of HPV meaningfully increased the risk of CIN3+ (or secondarily, CIN2+) above the risk based on the combination of pooled HPV and cytology cotesting results in a clinically actionable manner (i.e., warranting changing management from a 1-year follow-up to immediate colposcopy). Because only a random sample of the controls (and the large majority, but not all, of the cases) was genotyped, a weighted statistical analysis of the cases and controls based on the reciprocals of the fractions of cases and controls tested from the whole population was used. The weights were used in a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (using SUDAAN) to generate 3-year cumulative risks that accounted for censoring and incomplete follow-up.

The consideration of HPV types was hierarchical. In practical terms, for constructing a useful genotyping assay, the types must be included in order from most discriminatory to least. To determine this order, an iterative approach was used in which each of the preceding higher-risk types was excluded from consideration for the analyses of the remaining HPV types. Therefore, to determine the highest-risk type, 3-year risks were generated for each of the oncogenic HPV types in the whole population. The highest-risk HPV type, HPV16 from the first iteration, was then excluded from the population to generate a new cohort of HPV16-negative women. This HPV16-negative population was used to calculate the 3-year cumulative risk for each of the remaining non-HPV16 oncogenic types to find the HPV type with the second highest positive predictive value for CIN3+. From the HPV16-negative iteration, the HPV type with the highest 3-year cumulative risk was HPV33; this was then excluded from the population of HPV16-negative women to create a population of HPV16- and HPV33-negative women to be used in the next iteration in order to find the HPV type with the third highest 3-year cumulative risk, and so on.

In summary, we looked at each HPV type individually and chose the one with the highest positive predictive value for the 3-year risk of CIN3+, which was HPV16 (see Results). We then sought to determine, given an HPV16-negative status, whether testing positive for any other type would indicate the need for colposcopic referral. Consequently, we excluded all women testing positive for HPV16 and repeated the risk calculations among the remaining women, and so on. In this manner, we ascertained, in hierarchical order, the value of sequentially adding individual types to a typing assay. We performed a similar analysis, making CIN2+ the clinical endpoint.

RESULTS

As shown in Fig. 1, the study population consisted of 18,810 women with HPV-positive/cytology-negative results. The median age at enrollment was 40 years, the IQR (interquartile range) was 34 to 50 years, and the full range was 30 to 90 years. The median time from enrollment, HPV-positive/cytology-negative result to case diagnosis, or last follow-up cotest was 475 days, with a mean of 642 days, an IQR of 0 to 1,077 days, and a maximum of 2,217 days.

The frequency and percentage of each high-risk HPV type for each of the diagnostic groups (CIN3+, CIN2, and <CIN2) are shown in Table 1. Because women who had infections with >1 type were counted for each positive type in this table, the rows do not sum to 100%. HPV16 was associated with the largest percentage of prevalent and incident CIN3+ and CIN2; it was also the most prevalent type in women with <CIN2.

TABLE 1.

Cases and controls by HPV type positivity

| HPV type | HPV positive by grade: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <CIN2 |

CIN2 |

CIN3+ |

||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 16 | 462 | 13.1 | 143 | 23.7 | 215 | 44.6 |

| 18 | 209 | 5.9 | 46 | 7.6 | 53 | 11.0 |

| 31 | 335 | 9.5 | 89 | 14.8 | 67 | 13.9 |

| 33 | 73 | 2.1 | 10 | 1.7 | 20 | 4.2 |

| 35 | 144 | 4.1 | 40 | 6.6 | 26 | 5.4 |

| 39 | 264 | 7.5 | 41 | 6.8 | 21 | 4.4 |

| 45 | 192 | 5.5 | 24 | 4.0 | 15 | 3.1 |

| 51 | 249 | 7.1 | 43 | 7.1 | 16 | 3.3 |

| 52 | 368 | 10.5 | 96 | 15.9 | 54 | 11.2 |

| 56 | 223 | 6.3 | 31 | 5.1 | 10 | 2.1 |

| 58 | 208 | 5.9 | 41 | 6.8 | 15 | 3.1 |

| 59 | 225 | 6.4 | 28 | 4.6 | 16 | 3.3 |

| 66 | 177 | 5.0 | 19 | 3.2 | 14 | 2.9 |

| 68 | 183 | 5.2 | 26 | 4.3 | 8 | 1.7 |

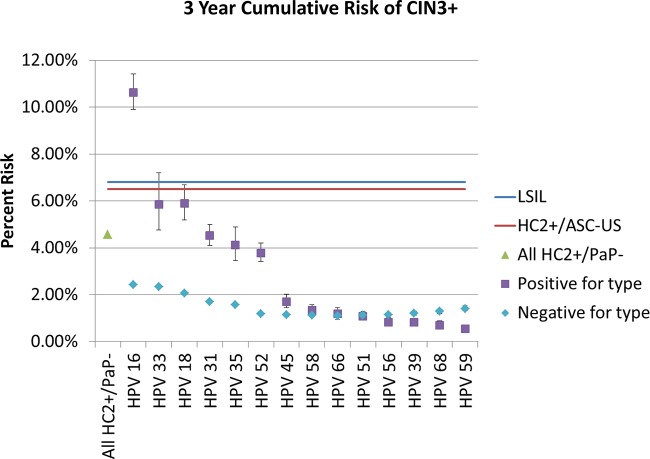

Using weighting by the sampling fractions (see Materials and Methods), we estimated the cumulative risks (positive predictive values and complements of the negative predictive values) of CIN3+ following detection (or not) of each individual HPV type. In Fig. 2, we show the risks of CIN3+, in descending order, from greatest to least. The corresponding data are tabulated in Table 2. In comparison, we show the 3-year CIN3+ risks of LSIL and HPV-positive ASC-US in the PaP cohort, two results that are managed by immediate colposcopic referral. Among all women with HC2-positive, cytology-negative results (managed by 1-year return in current practice), the 3-year cumulative risk of CIN3+ (prevalent and incident cases combined) was 4.6% (a result that currently would lead to 1-year return testing at KPNC). This is slightly lower than the risks for LSIL (6.8%) and HPV-positive ASC-US (6.5%), two results currently managed by immediate colposcopy. Thus, the implicitly accepted colposcopy referral thresholds are >4.6% and ≤6.5% 3-year risk of CIN3, as applied to this study population. Any HPV genotype leading to a risk of >6.5%, to be consistent with existing and accepted practice, would result in a colposcopy referral.

FIG 2.

Three-year HPV type-specific cumulative risk of CIN3+. The purpose of the analysis was to explore whether finding any specific types of HPV elevates the risk of CIN3+ among women with HPV-positive NILM cytology to the point of warranting immediate colposcopy rather than a return visit at 1 year. According to the current U.S. guidelines, the benchmark risk for immediate colposcopy is set by the risk of LSIL cytology or HPV-positive ASC-US; for the 3-year cumulative risk, these benchmarks are 6.8% and 6.5%, respectively (shown as blue and red lines, respectively). The corresponding 3-year risk for HC2-positive NILM is lower, at 4.6% (green triangle), and is managed by 1-year return in the absence of knowing the specific HPV type. However, the data indicate that HPV16-positive women have an elevated risk (10.6%) that justifies immediate colposcopic referral. The type-specific risks for other types (positive and negative) are shown hierarchically in order of decreasing magnitude when positive, in the absence of higher-risk types, with 95% confidence intervals. The HPV33- and HPV18-positive risks nearly reach the benchmark risks for immediate colposcopic referral. No other types approach a risk that would warrant colposcopic referral.

TABLE 2.

Hierarchical risk of CIN3 or worse among women aged ≥30 years who are HC2 positive with NILM cytologya

| HPV type | Type-specific HPV+ 3-yr risk (%) | 95% CI limits (%) |

Type-specific HPV− 3-yr risk (%) | 95% CI limits (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| hpv_16 | 10.63 | 9.89 | 11.41 | 2.43 | 2.37 | 2.49 |

| hpv_33 | 5.86 | 4.77 | 7.20 | 2.34 | 2.28 | 2.40 |

| hpv_18 | 5.89 | 5.18 | 6.69 | 2.07 | 2.02 | 2.13 |

| hpv_31 | 4.53 | 4.10 | 5.00 | 1.70 | 1.65 | 1.76 |

| hpv_35 | 4.11 | 3.46 | 4.89 | 1.57 | 1.51 | 1.63 |

| hpv_52 | 3.78 | 3.40 | 4.20 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.23 |

| hpv_45 | 1.71 | 1.43 | 2.03 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.19 |

| hpv_58 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 1.58 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.17 |

| hpv_66 | 1.18 | 0.96 | 1.45 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.17 |

| hpv_51 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 1.31 | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.18 |

| hpv_56 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1.22 |

| hpv_39 | 0.83 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 1.29 |

| hpv_68 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.88 | 1.29 | 1.20 | 1.38 |

| hpv_59 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 1.41 | 1.31 | 1.52 |

| Overall HC2 positive | 4.57 | |||||

Positive and negative status statistics refer to the types indicated in the respective rows. The risks are hierarchical, as explained in Materials and Methods.

Of the carcinogenic HPV types, HPV16 conferred the greatest type-specific risk of CIN3+; HPV16-positive women had a 3-year risk of CIN3+ of 10.6%, while HPV16-negative women had a much lower risk of 2.4%. Among the HPV16-negative women, the next most informative HPV type was HPV33, with a 3-year risk of 5.9% when positive and 2.3% when negative. Considered sequentially (i.e., among HPV16- and HPV33-negative women), the next most informative HPV type was HPV18, with a 5.9% risk in positive women. The detection of each of the remaining types minimally influenced the risk of CIN3+ compared to that of the overall HC2-positive population. In fact, women positive for several of the types (e.g., HPV51, HPV56, HPV39, HPV68, and HPV59) had a lowered risk than did women with an HC2-positive result who were negative for those lower-risk types.

We repeated the same analysis, restricted first to prevalent cases (prevalent risk) and then to 3-year risk of incident CIN3+ (data not shown). The prevalent analysis focused on the risk of CIN3+ immediately subsequent to the HPV typing of HPV-positive/cytology-negative results (Burk laboratory); the incident case analysis focused on the risk of CIN3+ during follow-up, excluding the prevalent cases (Roche Molecular Systems laboratory). We saw roughly similar trends in the two analyses; the three highest risks for the prevalent cases were seen for HPV33, HPV16, and then HPV18. For the incident cases, the order was HPV16, HPV18, and HPV33.

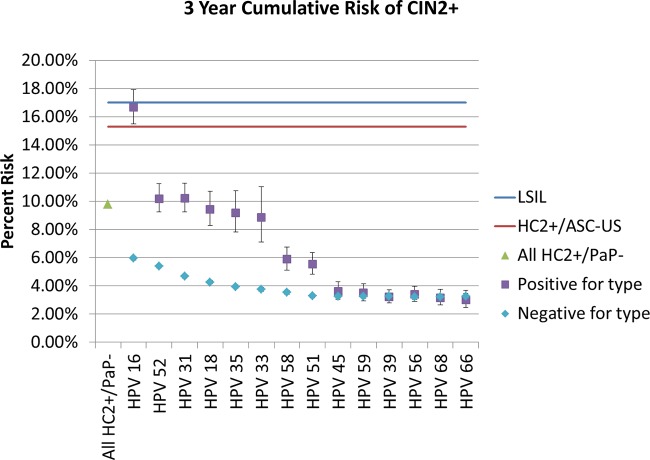

The choice of outcome influenced the estimates; when we repeated the analysis using CIN2+ rather than CIN3+ (3-year risk of CIN2+ among women with HC2-positive, cytology-negative results, 9.8%; LSIL, 17.0%; HPV-positive ASC-US, 15.3%), the ordering was somewhat altered (Fig. 3). The corresponding data are tabulated in Table 3. Although HPV16 positivity still conveyed the highest absolute risk of any individual type, HPV52 and HPV31 had the next highest risks. No type other than HPV16 exceeded the implicit colposcopy threshold established by LSIL or HPV-positive ASC-US results.

FIG 3.

Three-year HPV type-specific cumulative risk of CIN2+. The analysis from Fig. 2 is repeated, but including CIN2 as part of the targeted disease endpoint alters somewhat the order of the risk of specific HPV types. HPV16 remains the only type whose detection exceeds the benchmark risk threshold for colposcopic referral. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical risk of CIN2 or worse by genotype among women aged ≥30 years who are HC2 positive with NILM cytologya

| HPV type | Type-specific HPV+ 3-yr risk (%) | 95% CI limits (%) |

Type-specific HPV− 3-yr risk (%) | 95% CI limits (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| hpv_16 | 16.66 | 15.49 | 17.91 | 5.96 | 5.84 | 6.08 |

| hpv_52 | 10.20 | 9.25 | 11.25 | 5.40 | 5.27 | 5.53 |

| hpv_31 | 10.23 | 9.27 | 11.29 | 4.69 | 4.56 | 4.82 |

| hpv_18 | 9.43 | 8.28 | 10.72 | 4.27 | 4.14 | 4.40 |

| hpv_35 | 9.19 | 7.84 | 10.76 | 3.94 | 3.82 | 4.07 |

| hpv_33 | 8.88 | 7.12 | 11.05 | 3.76 | 3.63 | 3.89 |

| hpv_58 | 5.89 | 5.13 | 6.76 | 3.54 | 3.42 | 3.68 |

| hpv_51 | 5.54 | 4.83 | 6.36 | 3.31 | 3.17 | 3.45 |

| hpv_45 | 3.63 | 3.06 | 4.31 | 3.27 | 3.13 | 3.42 |

| hpv_59 | 3.50 | 2.94 | 4.16 | 3.25 | 3.10 | 3.41 |

| hpv_39 | 3.23 | 2.80 | 3.74 | 3.25 | 3.09 | 3.43 |

| hpv_56 | 3.40 | 2.92 | 3.97 | 3.22 | 3.04 | 3.42 |

| hpv_68 | 3.16 | 2.64 | 3.77 | 3.24 | 3.04 | 3.45 |

| hpv_66 | 3.02 | 2.47 | 3.70 | 3.26 | 3.05 | 3.49 |

| Overall HC2 positive | 9.80 | |||||

Positive and negative status statistics refer to the types indicated in the respective rows. The risks are hierarchical, as explained in Materials and Methods.

Most cases of AIS and adenocarcinoma were HPV16 positive. However, 20 of 71 (28%) cases of cervical AIS and adenocarcinoma were HPV18 positive. Only 4 were HPV45 positive.

DISCUSSION

Tests designed to stratify risk, such as HPV genotyping, are most useful clinically when the results help direct management. Conversely, if the subsequent clinical steps are the same regardless of test outcome, the value is questionable. The decision following abnormal cervical cotesting results is whether to refer a woman immediately for colposcopy or to follow her at some interval by repeat testing. Our data support the usefulness of genotyping for types HPV16 and HPV18.

Only HPV16 positivity was associated with a risk that clearly exceeded the KPNC and U.S. consensus threshold for immediate referral for colposcopy (i.e., the accepted practice based on the results of LSIL or HPV-positive ASC-US, or approximately a 5 to 6% 3-year risk of CIN3+ as applied to this population) (9, 10). This is a potentially useful result, because it might change management for HPV16-positive women from 1-year return for retesting to immediate colposcopy and possibly earlier treatment of CIN2+ lesions.

The latest U.S. consensus guidelines for management already recommend the referral of women with HPV16 or HPV18 infection and normal cytologic results for colposcopy (1, 10). Of note, this is the only currently recommended use of HPV genotyping. Those recommendations were based largely on evidence from long-term observational research cohorts. The present study supports the guidelines regarding HPV16 based on the genotyping of HPV specimens from a large real-life clinical experience at KPNC.

The management guidelines also recommend referring women with HPV18 infection and normal cytologic results for colposcopy (1, 10); in terms of stratifying the risk of CIN3+, the present study provides some support for this recommendation. The women in this study with HPV18 infection had a 3-year risk of CIN3+ just at the threshold for colposcopic referral. Moreover, HPV18 infection was associated with a sizable minority of cases of invasive and in situ adenocarcinoma; these cases are of special concern because they are difficult to detect by cytologic screening. In this context, our data also provide support for the current guidelines recommending immediate colposcopic evaluation of HPV18-infected women.

On the other hand, these particular data do not strongly support a referral for colposcopy in cytologically normal women with HPV45, which is related to HPV18 and also thought to be related to glandular lesions. The risk of CIN3+ was lower than that among the total group of women with HC2-positive results and did not exceed the colposcopy threshold. Few cases of invasive or in situ adenocarcinoma were associated with HPV45. One FDA-approved assay combines HPV45 with HPV18 as a typing result (19). The fraction of cervical cancer caused by HPV45 is greater in other regions of the world, but we failed to find corroborative evidence in this U.S. cohort, perhaps due to small numbers or limited follow-up.

HPV33 ranked second in our data in distinguishing the risk of CIN3+. There is evidence from other cohorts as well that HPV33 is a particularly high-risk HPV type in terms of absolute risk (positive predictive value) (20), although the fraction of cancers caused by HPV33 globally is not particularly large. The value of distinguishing HPV33 deserves further study.

Otherwise, the KPNC data suggested a less clear value for broader HPV genotyping of women with HPV-positive/Pap-negative cotest results. Clinical management would not be clearly altered by knowing each of the separate types. For example, our data did not indicate that it would be worthwhile to determine HPV31 positivity separately, despite its known role (along with that of HPV16, HPV18, and HPV45) as a leading cause of cervical cancer worldwide (21, 23). The results of this large prospective analysis in a northern Californian population, with mainly precancer as the disease outcome, must be considered along with the long-term prospective studies and international cervical cancer typing data to reach an optimal conclusion regarding the design of HPV tests that yield various degrees of genotyping results.

Interestingly, for some of the types, testing positive implied a lower risk than testing negative for that type. Of note, all the women had HC2-positive results, and some high-risk genotypes were missed in the typing assays. Also, perhaps some of the untargeted types detected by the cross-reactivity of HC2 (and found by LA, e.g., HPV53 or HPV73; data not shown) conveyed a higher cumulative risk of CIN3 (although probably not invasive cancer) than the lowest-risk targeted types.

Our use of CIN3+ as the ethical surrogate for cancer risk in prospective studies that influence guidelines is not ideal, as illustrated by the discussion on HPV18 (which is disproportionately important for cancers compared with CIN3). The choice of endpoint is important, as shown by our examination of CIN2+. CIN2 is an equivocal high-grade endpoint, caused by an appreciably different group of HPV types than those for CIN3 or cancer (22). It is noteworthy that had we used CIN2+ as our primary disease endpoint, we would have found an increased role for HPV52 and HPV31 and a decreased role for HPV18 and HPV33, although the increased risk for HPV16 remained the strongest finding.

The strength of this study was the unusually large size of the HPV-positive cohort, derived from a larger HC2-tested cohort of more than half a million women seen at KPNC during the study period. The large cohort size permitted us to look at the risks of CIN3+ of different individual HPV types with good precision.

Some limitations should be noted, however. The HPV-positive cohort was established by routine HC2 testing of the clinical specimen that was collected second (i.e., the HPV test specimen was collected after the cytology specimen), which might have reduced the detection of HPV-positive specimens with viral loads below the clinical cutoff for HC2. Research HPV genotyping was performed in 2 separate laboratories by different PCR-based techniques that do not perfectly agree with each other or with HC2. Another combination of test methods, or the testing of the cervical specimens collected first, might have led to slightly different risk estimates for the individual HPV types, although it is doubtful that the main conclusions as to relative type importance would be altered. Also, there was no independent cytology or pathology review in this study; instead, we used routine KPNC diagnoses. Finally, our analysis did not take into account the uncertainty associated with each cut in the algorithm that ordered the types from most to least discriminatory.

In ongoing work, we will be extending the findings presented here using different FDA-approved assays to assess generalizability, as well as to address the more controversial role of HPV typing among women with ASC-US.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The field effort was a collaboration of the NCI and KPNC and was supported in part by the intramural program of the NCI. The statistical analysis was supported and led independently by the NCI. The genotyping at Roche Molecular Systems was funded by Roche. The genotyping at the laboratory of R.D.B. was supported by a collaborative agreement between AECOM and NCI.

Some of the testing of the specimens was provided by Roche at no cost to NCI. S.B., J.R.K., C.A., T.T., H.E., and R.A. were employees of Roche Molecular Systems at the time the study was conducted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, Killackey M, Kulasingam SL, Cain JM, Garcia FA, Moriarty AT, Waxman AG, Wilbur DC, Wentzensen N, Downs LS Jr, Spitzer M, Moscicki AB, Franco EL, Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Myers ER. 2012. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis 16:175–204. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31824ca9d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meijer CJ, Berkhof H, Heideman DA, Hesselink AT, Snijders PJ. 2009. Validation of high-risk HPV tests for primary cervical screening. J Clin Virol 46(Suppl 3):S1–S4. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(09)00540-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, Wright TL, Behrens CM. 2011. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol 12:880–890. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, Kitchener H, Segnan N, Gilham C, Giorgi-Rossi P, Berkhof J, Peto J, Meijer CJLM, International HPV Screening Working Group . 2013. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 383:524–532. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, Hingmire S, Malvi SG, Thorat R, Kothari A, Chinoy R, Kelkar R, Kane S, Desai S, Keskar VR, Rajeshwarkar R, Panse N, Dinshaw KA. 2009. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med 360:1385–1394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, van Kemenade FJ, Coupe VM, Hesselink AT, Rozendaal L, Heideman DA, Verheijen RH, Bulk S, Verweij WM, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ. 2012. Evaluation of 14 triage strategies for HPV DNA-positive women in population-based cervical screening. Int J Cancer 130:602–610. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox JT, Castle PE, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Wright TC Jr, Cuzick J, Athena HPV Study Group . 2013. Comparison of cervical cancer screening strategies incorporating different combinations of cytology, HPV testing, and genotyping for HPV 16/18: results from the ATHENA HPV study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 208:184.e1–184.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Gage JC, Kinney WK. 2013. Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women who test Pap-negative but are HPV-positive. J Low Genit Tract Dis 17:S56–S63. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285437b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Gage JC, Kinney WK. 2013. Benchmarking CIN 3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Low Genit Tract Dis 17:S28–S35. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285423c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wentzensen N, Lawson HW. 2013. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis 17:S1–S27. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, Lorey T, Poitras NE, Cheung L, Demuth F, Schiffman M, Wacholder S, Castle PE. 2011. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol 12:663–672. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0 (Erratum, 12:722, 2011.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen HC, Schiffman M, Lin CY, Pan MH, You SL, Chuang LC, Hsieh CY, Liaw KL, Hsing AW, Chen CJ, CBCSP-HPV Study Group . 2011. Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection and increased long-term risk of cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:1387–1396. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiffman M, Wentzensen N. 2013. Human papillomavirus infection and the multistage carcinogenesis of cervical cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22:553–560. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinkelspiel H, Fetterman B, Poitras N, Kinney W, Cox JT, Lorey T, Castle PE. 2014. Cervical cancer rates after the transition from annual Pap to 3-year HPV and Pap. J Low Genit Tract Dis 18:57–60. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31829325c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castle PE, Shaber R, LaMere BJ, Kinney W, Fetterma B, Poitras N, Lorey T, Schiffman M, Dunne A, Ostolaza JM, McKinney S, Burk RD. 2011. Human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes in women with cervical precancer and cancer at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20:946–953. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castle PE, Stoler MH, Solomon D, Schiffman M. 2007. The relationship of community biopsy-diagnosed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 to the quality control pathology-reviewed diagnoses: an ALTS report. Am J Clin Pathol 127:805–815. doi: 10.1309/PT3PNC1QL2F4D2VL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gage JC, Sadorra M, Lamere BJ, Kail R, Aldrich C, Kinney W, Fetterman B, Lorey T, Schiffman M, Castle PE, PaP Cohort Study Group . 2012. Comparison of the Cobas human papillomavirus (HPV) test with the Hybrid Capture 2 and Linear Array HPV DNA tests. J Clin Microbiol 50:61–65. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05989-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castle PE, Schiffman M, Gravitt PE, Kendall H, Fishman S, Dong H, Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Lorincz A, Schussler JE, Burk RD. 2002. Comparisons of HPV DNA detection by MY09/11 PCR methods. J Med Virol 68:417–423. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arbyn M, Roelens J, Cuschieri K, Cuzick J, Szarewski A, Ratnam S, Reuschenbach M, Belinson S, Belinson JL, Monsonego J. 2013. The APTIMA HPV assay versus the Hybrid Capture 2 test in triage of women with ASC-US or LSIL cervical cytology: a meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy. Int J Cancer 132:101–108. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuzick J, Ho L, Terry G, Kleeman M, Giddings M, Austin J, Cadman L, Ashdown-Barr L, Costa MJ, Szarewski A. 2014. Individual detection of 14 high risk human papilloma virus genotypes by the PapType test for the prediction of high grade cervical lesions. J Clin Virol 60:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Franceschi S, Clifford GM. 2012. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn T, Zuna RE, Gold MA, Allen RA, Zhang R, Sherman ME, Wacholder S, Walker J, Wang SS. 2009. Multiple human papillomavirus genotype infections in cervical cancer progression in the study to understand cervical cancer early endpoints and determinants. Int J Cancer 125:2151–2158. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T. 2010. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1478–1488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]