Abstract

We describe a case of fatal fulminant hepatitis E concomitant to malignant B cell lymphoma in a 73-year-old French woman. Infection was with an autochthonous hepatitis E virus of genotype 3f. Frequent consumption of uncooked pig liver sausage (figatellu) was the only risk factor found.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old French woman was admitted on 29 April 2013 at an internal medicine unit due to weight loss, anorexia, nausea, and sweating. She had a history of essential hypertension, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, stroke, and arthrosis and was receiving oral anticoagulant, antiarrhythmic (atenolol and flecainide), antihypertensive (perindopril and indapamide), and antidepressant (venlafaxine) drugs. Physical examination revealed voluminous cervical, inguinal, and axillar lymph nodes and splenomegaly. Laboratory tests showed moderate thrombopenia, liver cytolysis with an 8-fold elevation of alanine aminotransferase level (ALT), cholestasis, hyperbilirubinemia, and a fallen prothrombin index (PI) (Table 1). Oral anticoagulant treatment was immediately stopped because of the low PI. Nevertheless, PI barely returned within normal ranges, ALT remained elevated, and hyperbilirubinemia still increased. On 5 May, histology of a cervical lymph node returned a diagnosis of B cell high-grade malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and the patient's general status had worsened, with occurrence of jaundice, drowsiness, and hypotension. Diagnosis of hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection was established on 14 May by HEV RNA detection in serum with an in-house PCR assay (1). HEV RNA load was 7.9 log10 copies/ml. Concurrently, anti-HEV IgM and IgG were detected by commercial enzymoimmunoassays (Wantai, Beijing, China) (2). Retrospective testing of a serum sample collected 5 days before admission showed HEV RNA detection around the positivity threshold of the PCR assay. Other major causes of acute liver diseases were excluded, as serological and molecular testing of hepatitis A, B, and C, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus was negative or indicated past infections, while searches for antinuclear auto-antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, and anti-liver kidney microsome antibodies were negative. No preexisting liver disease was known. The thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed multiple and diffuse lymph nodes; the cerebral CT scan showed no abnormality. Liver magnetic resonance imaging showed a splenic nodular lesion compatible with lymphoma. Liver lymphomatous infiltrate was suspected, but liver biopsy could not be performed. Ribavirin therapy (600 mg twice daily [b.i.d.]) was introduced on 15 May. On 24 May, the HEV RNA level showed a 1.5-log10 decrease, while ALT had decreased. Nevertheless, bilirubinemia and PI still worsened, and the patient's condition rapidly deteriorated, with hemodynamic instability despite support, which led to admission in an intensive care unit on 30 May. Ventricular fibrillation occurred, which led to death despite close cardiac massage. Chemotherapy had not yet been initiated.

TABLE 1.

Evolution of biochemical, hematological, and virological markers

| Parametera | Normal range | Value onb: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 April | 3 May | 6 May | 18 May | 28 May | ||

| Serum bilirubin (μmol/liter) | 5–20 | 62 | 105 | 152 | 327 | 512 |

| Serum ALT (IU/liter) | <31 | 263 | 245 | 212 | 123 | 83 |

| Serum ALKP (IU/liter) | <34 | 131 | 112 | 85 | 45 | 27 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/liter) | <10 | 54 | 53 | 71 | 59 | 116 |

| Prothrombin index (%) | 70–100 | 18 | 67 | 83 | 63 | 23 |

| White blood cell count (×109/liter) | 4–10 | 10.5 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 9 | 13.7 |

| Polynuclear neutrophil count (×109/liter) | 2–7.5 | 8.6 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 10.9 |

| Lymphocyte count (×109/liter) | 1.5–4 | 1.02 | 2.3 | 1.05 | 0.27 | 1.78 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.5–16 | 13.3 | 12.7 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 13.3 |

| Platelets (×109/liter) | 150–450 | 141 | 121 | 138 | 107 | 107 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase level; ALKP, alkaline phosphatase level.

Anticoagulant was discontinued on 29 April, ribavirin was introduced on 15 May, and the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit on 30 May.

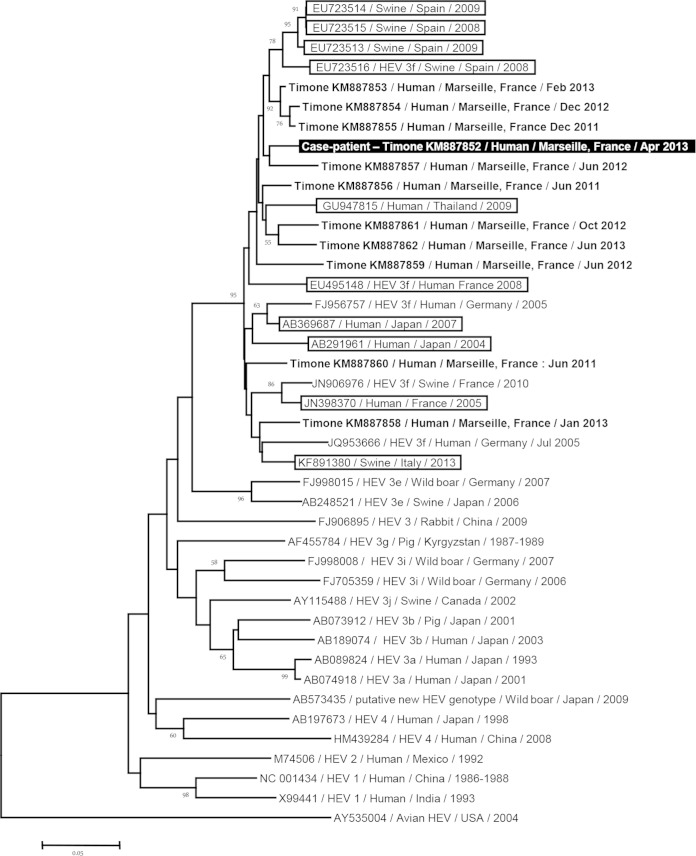

The patient had not recently traveled abroad nor had contact with travelers, a transfusion history, or contact with animals known as reservoirs of HEV. Regarding potential waterborne or food-borne HEV transmission, only frequent consumption of uncooked pig liver sausage (figatellu) was reported. We tested, as described previously (3), leftover pig liver sausage brought by the patient's family; we did not detect HEV RNA in the figatellu, but we may have missed the virus, as the leftover sausage sample was tested after it dried, or infection might have occurred while eating other figatelli, as the patient commonly ate such sausages. The HEV sequence (GenBank accession no. KM887852) obtained from the serum sample of the case patient was of genotype 3f, as determined by phylogenetic analysis of an open reading frame 2 fragment from the HEV genome (Fig. 1) (4). This finding was congruent with epidemiological data indicating autochthonous viral infection. Best matches for this HEV sequence in GenBank (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) were obtained from swine in Spain and Thailand and from humans in Japan and southwestern France, with sequence identities of 93 to 95%.

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on a 225-nucleotide partial sequence corresponding to nucleotides 6425 to 6649 of open reading frame 2 (ORF2) of the HEV genome (GenBank accession no. FJ956757). The HEV sequence obtained in the present study is indicated by a black background and a white font. The 10 sequences with the highest BLAST scores recovered from both GenBank (boxed) and Timone's database (boldfaced) were included, along with additional sequences representative of genotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4 and novel zoonotic strains. Nucleotide alignments were performed using the MUSCLE software (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/). The tree was constructed using the MEGA 6 software (http://www.megasoftware.net/) and the neighbor-joining method. Branches with bootstrap values were obtained from 1,000 resamplings of the data, and values of >50% are labeled on the tree. The avian HEV sequence AY535004 was used as an outgroup. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

We describe here, to our knowledge, the first fatal fulminant hepatitis E case in a patient with malignant B cell lymphoma. HEV infections represent an emerging clinical threat in Europe due to possible progression toward chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis in severely immunocompromised patients (5). In addition, fatal outcome was reported in 8 to 9% of cases in series of symptomatic acute HEV infections (6–11). These deaths occurred primarily in elderly persons and/or patients with preexisting liver diseases, but fulminant hepatitis E was also reported in persons without hepatopathy (8). In Marseille University hospitals, we have previously pointed out that acute hepatitis E was the leading cause of liver transplantation for virus-associated acute liver failure, concurrently with acute HBV infection (8). We previously described five fulminant and/or fatal acute hepatitis E strains (8). Among them, two involved HEV of subtype 3c, whereas three involved HEV-3f that displayed only 91% to 92% identity with the HEV sequence recovered here. In addition, best matches for the sequence obtained here were not involved in fatal or fulminant cases (Fig. 1). Autochthonous hepatitis E was previously reported in patients with hematological diseases, including acute or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (12–16). Fatal evolution was described only once, associated with pericardial effusion related to acute liver failure in a patient severely immunocompromised due to leukemia, chemotherapy, and stem cell transplantation (12). No preexisting liver disease was reported in this case, which suggests that HEV infection can trigger acute liver failure in patients with hematological malignancies. In addition, it was reported that lymphoma itself can cause acute liver failure and infiltration (17). Here, lymphomatous infiltrate of the liver was suspected but could not be documented. Ribavirin therapy, which is highly efficient in curating HEV chronically infected patients (18), was associated with rapid HEV clearance in previous reports of severe acute hepatitis E (19–21). A 1.5-log10 HEV RNA load reduction was observed in the present case after 9 days of ribavirin therapy, which is similar to what was reported previously in ribavirin treatment of acute hepatitis E, but the clinical context with B cell lymphoma and possible concurrent liver lymphomatous infiltrate may have contributed to the poor biological and clinical evolution.

Pig liver sausages have been identified as a source of hepatitis E in France and Europe (3, 22, 23). In France, HEV RNA was detected from 4% of pigs entering the food chain (24). In addition, 7/12 and 9/18 pig liver sausages from southeastern and southwestern France, respectively, tested HEV RNA positive (3, 25), and HEV was cultured from 1 of 4 figatelli (pig liver sausage from southeastern France) (26). HEV RNA was also detected from 6 to 10% of pork sausages in the United Kingdom and Spain (27, 28). Our 2010 study (3) was influential in implementing the mandatory notification by the manufacturer that these sausages must be eaten after thorough cooking, but this notification is usually poorly legible. Although we could not definitively connect here HEV infection and pig liver sausage consumption, the latter was the only identified risk factor.

Taken together, previous data prompt to test for HEV in cases of severe acute liver failure in patients with hematological malignancies and to inform more widely on the risk of acquiring HEV through the consumption of pig liver sausage if eaten uncooked, which may prevent other cases of this potentially fatal infection.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Sequences from this study were submitted to GenBank under accession no. KM887852 to KM887862.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We have no potential conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Doudier B, Vencatassin H, Aherfi S, Colson P. 2014. Fatal fulminant hepatitis E associated with autoimmune hepatitis and excessive paracetamol intake in southeastern France. J Clin Microbiol 52:1294–1297. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03372-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossi-Tamisier M, Moal V, Gerolami R, Colson P. 2013. Discrepancy between anti-hepatitis E virus immunoglobulin G prevalence assessed by two assays in kidney and liver transplant recipients. J Clin Virol 56:62–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colson P, Borentain P, Queyriaux B, Kaba M, Moal V, Gallian P, Heyries L, Raoult D, Gerolami R. 2010. Pig liver sausage as a source of hepatitis E virus transmission to humans. J Infect Dis 202:825–834. doi: 10.1086/655898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colson P, Romanet P, Moal V, Borentain P, Purgus R, Benezech A, Motte A, Gerolami R. 2012. Autochthonous infections with hepatitis E virus genotype 4, France. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1361–1364. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamar N, Bendall R, Legrand-Abravanel F, Xia NS, Ijaz S, Izopet J, Dalton HR. 2012. Hepatitis E. Lancet 379:2477–2488. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61849-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockwood GL, Fernandez-Barredo S, Bendall R, Banks M, Ijaz S, Dalton HR. 2008. Hepatitis E autochthonous infection in chronic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:800–803. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f1cbff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalton HR, Stableforth W, Thurairajah P, Hazeldine S, Remnarace R, Usama W, Farrington L, Hamad N, Sieberhagen C, Ellis V, Mitchell J, Hussaini SH, Banks M, Ijaz S, Bendall RP. 2008. Autochthonous hepatitis E in southwest England: natural history, complications and seasonal variation, and hepatitis E virus IgG seroprevalence in blood donors, the elderly and patients with chronic liver disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 20:784–790. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f5195a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aherfi S, Borentain P, Raissouni F, Le GA, Guisset M, Renou C, Grimaud JC, Hardwigsen J, Garcia S, Botta-Fridlund D, Nafati C, Motte A, Le Treut YP, Colson P, Gerolami R. 2014. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure related to autochthonous genotype 3 hepatitis E virus infection. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 38:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peron JM, Bureau C, Poirson H, Mansuy JM, Alric L, Selves J, Dupuis E, Izopet J, Vinel JP. 2007. Fulminant liver failure from acute autochthonous hepatitis E in France: description of seven patients with acute hepatitis E and encephalopathy. J Viral Hepat 14:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalton HR, Hazeldine S, Banks M, Ijaz S, Bendall R. 2007. Locally acquired hepatitis E in chronic liver disease. Lancet 369:1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peron JM, Mansuy JM, Poirson H, Bureau C, Dupuis E, Alric L, Izopet J, Vinel JP. 2006. Hepatitis E is an autochthonous disease in industrialized countries. Analysis of 23 patients in South-West France over a 13-month period and comparison with hepatitis A. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 30:757–762. http://www.em-consulte.com/showarticlefile/129912/index.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfefferle S, Frickmann H, Gabriel M, Schmitz N, Gunther S, Schmidt-Chanasit J. 2012. Fatal course of an autochthonous hepatitis E virus infection in a patient with leukemia in Germany. Infection 40:451–454. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauss A, Wenzel JJ, Flechtenmacher C, Navid MH, Eisenbach C, Jilg W, Stremmel W, Schnitzler P. 2012. Chronic hepatitis E virus infection in a patient with leukemia and elevated transaminases: a case report. J Med Case Rep 6:334. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-6-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giordani MT, Fabris P, Brunetti E, Goblirsch S, Romano L. 2013. Hepatitis E and lymphocytic leukemia in Man, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 19:2054–2056. doi: 10.3201/eid1912.130521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Coutre P, Meisel H, Hofmann J, Rocken C, Vuong GL, Neuburger S, Hemmati PG, Dorken B, Arnold R. 2009. Reactivation of hepatitis E infection in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Gut 58:699–702. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.165571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ollier L, Tieulie N, Sanderson F, Heudier P, Giordanengo V, Fuzibet JG, Nicand E. 2009. Chronic hepatitis after hepatitis E virus infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma taking rituximab. Ann Intern Med 150:430–431. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lettieri CJ, Berg BW. 2003. Clinical features of non-Hodgkins lymphoma presenting with acute liver failure: a report of five cases and review of published experience. Am J Gastroenterol 98:1641–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamar N, Izopet J, Tripon S, Bismuth M, Hillaire S, Dumortier J, Radenne S, Coilly A, Garrigue V, D'alteroche L, Buchler M, Couzi L, Lebray P, Dharancy S, Minello A, Hourmant M, Roque-Afonso AM, Abravanel F, Pol S, Rostaing L, Mallet V. 2014. Ribavirin for chronic hepatitis E virus infection in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med 370:1111–1120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peron JM, Dalton H, Izopet J, Kamar N. 2011. Acute autochthonous hepatitis E in Western patients with underlying chronic liver disease: a role for ribavirin? J Hepatol 54:1323–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerolami R, Borentain P, Raissouni F, Motte A, Solas C, Colson P. 2011. Treatment of severe acute hepatitis E by ribavirin. J Clin Virol 52:60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins A, Lambert D, Ehrhard F, Brodard V, Hentzien M, Lebrun D, Nguyen Y, Tabary T, Peron JM, Izopet J, Bani-Sadr F. 2014. Severe acute hepatitis E in an HIV infected patient: successful treatment with ribavirin. J Clin Virol 60:422–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Purcell RH, Emerson SU. 2010. Hidden danger: the raw facts about hepatitis E virus. J Infect Dis 202:819–821. doi: 10.1086/655900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Said B, Ijaz S, Chand MA, Kafatos G, Tedder R, Morgan D. 2014. Hepatitis E virus in England and Wales: indigenous infection is associated with the consumption of processed pork products. Epidemiol Infect 142:1467–1475. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose N, Lunazzi A, Dorenlor V, Merbah T, Eono F, Eloit M, Madec F, Pavio N. 2011. High prevalence of hepatitis E virus in French domestic pigs. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 34:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansuy JM, Bendall R, Legrand-Abravanel F, Saune K, Miedouge M, Ellis V, Rech H, Destruel F, Kamar N, Dalton HR, Izopet J. 2011. Hepatitis E virus antibodies in blood donors, France. Emerg Infect Dis 17:2309–2312. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.110371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berto A, Grierson S, Hakze-van der Honing R, Martelli F, Johne R, Reetz J, Ulrich RG, Pavio N, van der Poel WH, Banks M. 2013. Hepatitis E virus in pork liver sausage, France. Emerg Infect Dis 19:264–266. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.121255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Bartolo I, Diez-Valcarce M, Vasickova P, Kralik P, Hernandez M, Angeloni G, Ostanello F, Bouwknegt M, Rodriguez-Lazaro D, Pavlik I, Ruggeri FM. 2012. Hepatitis E virus in pork production chain in Czech Republic, Italy, and Spain, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1282–1289. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berto A, Martelli F, Grierson S, Banks M. 2012. Hepatitis E virus in pork food chain, United Kingdom, 2009–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1358–1360. doi: 10.3201/eid1808.111647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]