LETTER

The pattern of symptoms caused by Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O91 in Japan differs from that in European countries. STEC O91 is often isolated from sporadic adult cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) in France (1), while in Germany, STEC O91 with sequence type 442 (ST442) occasionally causes HUS (2). In Japan, STEC O91 is a major non-O157 STEC O serogroup, and it is isolated mainly from asymptomatic carriers (for surveillance data, see http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/en/typhi-m/iasr-reference/230-iasr-data/2972-iasr-table-be-p.html [accessed 10 September 2014]). However, it is occasionally found in patients with minor symptoms, such as abdominal pain and watery diarrhea without HUS (3). The reasons for the differences in virulence of this enteropathogen between Japan and European countries remain unknown. Mellmann et al. subtyped STEC O91 isolates using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis and reported that all O91 isolates of ST33, and all single-locus variants, could be serotyped as O91:H14, O91:nonmotile, or O91:untypeable and demonstrated relatively low pathogenicity in humans (asymptomatic infection or causing watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, or bloody stool without HUS) (2).

We characterized 50 STEC O91 isolates from humans in Japan by MLST, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and virulence-related gene detection. Six isolates were obtained from patients with watery diarrhea and abdominal pain but without HUS, fever, or bloody stool, and 44 isolates were obtained from asymptomatic carriers. Forty-eight of the isolates investigated in this study accounted for ∼23% of all STEC O91 isolates (n = 210) reported in Japan from 2000 to 2011 (for surveillance data, see http://www.nih.go.jp/niid/en/typhi-m/iasr-reference/230-iasr-data/2972-iasr-table-be-p.html [accessed 10 September 2014]).

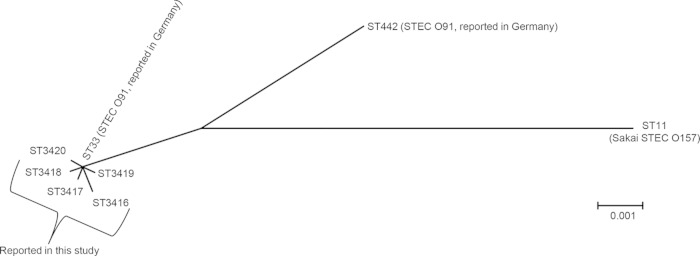

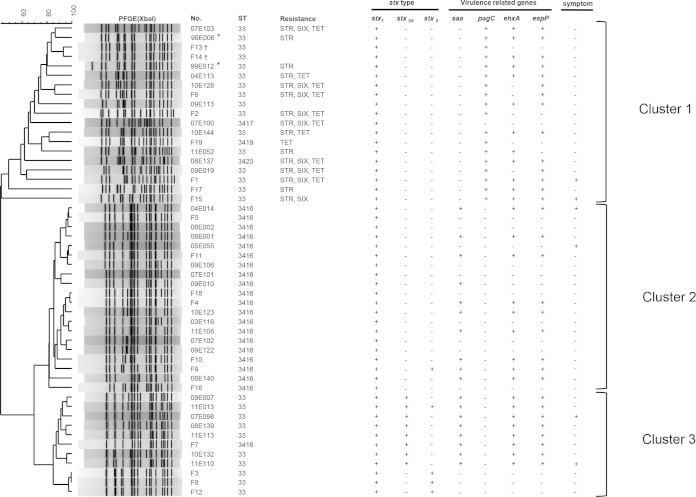

Sequences were submitted to the MLST database maintained by the University of Warwick (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/) and were assigned existing or novel allele type numbers and ST numbers defined by the database. The isolates were classified into six STs: ST33 (n = 26), ST3416 (n = 20), and ST3417, ST3418, ST3419, and ST3420 (n = 1 per ST) (Fig. 1). These six STs differed from each other by 1 to 3 bp across the 3,423-bp sequence region, whereas they differed by at least 23 bp from ST442. According to fliC typing with HhaI restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (4) and DNA sequencing, all isolates were flagellar genotype H14. stx2 genotyping showed seven, four, and one isolate(s) had stx2b, stx2a, and both stx2a and stx2b, respectively (Fig. 2). The isolates were assigned into three PFGE clusters. The first contained mainly ST33 isolates with resistance to one or more antimicrobials (cluster 1), the second contained only ST3416 isolates that were susceptible to all the tested antimicrobials (cluster 2), and the third contained ST33 isolates with no antimicrobial resistance (cluster 3). Interestingly, saa (autoagglutinating adhesin)-positive isolates were susceptible to all the tested antimicrobials, and pagC (outer membrane invasion protein)-positive isolates never overlapped with saa-positive isolates (Fig. 2). However, no significant association between any of the virulence-related genes and symptoms was detected with Fisher's exact test using SAS Software, version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing nucleotide sequence clusters of the tested Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O91 isolates obtained using multilocus sequence typing. ST442 and ST11 are included as outgroups. The isolates are classified into six sequence types (STs) (ST33 and ST3416 to ST3420). No strains tested belonged to ST442, which is a common ST in German hemolytic-uremic syndrome patients. The scale bar indicates the number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

FIG 2.

Dendrogram of pulsed-field gel electrophoreses profiles for Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O91 following XbaI digestion. Additional information associated with each isolate, including sequence types, resistance patterns, stx types, carriage of virulence-related genes, and symptoms, are indicated on the right of the dendrogram. The scale indicates the percent similarity, determined using Dice coefficients. Each pair of isolates indicated with an asterisk or dagger was isolated from both the individual and her/his contact. Ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, kanamycin, nalidixic acid, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, gentamicin, tetracycline, and cefixime were used in the antimicrobial susceptibility test. STR, streptomycin; SIX sulfisoxazole, TET, tetracycline. All isolates contained stx1, iha (iron-regulated gene A homolog adhesin), and lpfAO26 (major subunit of long polar fimbriae of STEC O26), while none of the isolates contained eae (intimin), irp2 (iron-repressible protein 2), fyuA (ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor), efa-1 (enterohemorrhagic E. coli factor for adherence), sfpA (major fimbrial subunit of Sfp fimbriae), bfpA (major pilin structural unit bundling), or cdt (cytolethal distending toxin). saa (autoagglutinating adhesin), pagC (OI-122) (outer membrane invasion protein), ehxA (enterohemorrhagic E. coli hemolysin), and espP (extracellular serine protease) were detected in 18 (36%), 18 (36%), 29 (58%), and 31 (62%) isolates, respectively. The only symptoms exhibited by patients were watery diarrhea and abdominal pain.

Because only 50 isolates from non-HUS patients or asymptomatic carriers were tested in the present study, further analyses are needed to determine the virulence of O91 lineages belonging to ST33 and its closely related STs. However, the information provided supports the hypothesis that differences in virulence associated with STs of O91 lineage strains might explain the differences in symptom patterns between individuals from Europe and Japan.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of fliC and stx2 determined in the present study were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) under accession numbers AB781285 to AB781292 and AB854278 to AB854290, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (H24-Shinko-Ippan-005). The MLST data are publicly available at http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/, which is currently supported by a grant from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC).

We thank T. Hirata, Fukuoka Institute of Health and Environmental Sciences, for invaluable advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonnet R, Souweine B, Gauthier G, Rich C, Livrelli V, Sirot J, Joly B, Forestier C. 1998. Non-O157:H7 Stx2-producing Escherichia coli strains associated with sporadic cases of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in adults. J Clin Microbiol 36:1777–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellmann A, Fruth A, Friedrich AW, Wieler LH, Harmsen D, Werber D, Middendorf B, Bielaszewska M, Karch H. 2009. Phylogeny and disease association of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O91. Emerg Infect Dis 15:1474–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Infectious Diseases. 2010. Trend in reported numbers of EHEC O91 infection and its characteristics, 2005–2009—NESID. Infect Agents Surveill Rep 31:169–170. (In Japanese.) http://idsc.nih.go.jp/iasr/31/364/dj364e.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado J, Grimont F, Grimont PA. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Res Microbiol 151:535–546. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]