Abstract

Analysis of maximum depth of occurrence of 11 952 marine fish species shows a global decrease in species number (N) with depth (x; m): log10N = −0·000422x + 3·610000 (r2 = 0·948). The rate of decrease is close to global estimates for change in pelagic and benthic biomass with depth (−0·000430), indicating that species richness of fishes may be limited by food energy availability in the deep sea. The slopes for the Classes Myxini (−0·000488) and Actinopterygii (−0·000413) follow this trend but Chondrichthyes decrease more rapidly (−0·000731) implying deficiency in ability to colonize the deep sea. Maximum depths attained are 2743, 4156 and 8370 m for Myxini, Chondrichthyes and Actinopterygii, respectively. Endemic species occur in abundance at 7–7800 m depth in hadal trenches but appear to be absent from the deepest parts of the oceans, >9000 m deep. There have been six global oceanic anoxic events (OAE) since the origin of the major fish taxa in the Devonian c. 400 million years ago (mya). Colonization of the deep sea has taken place largely since the most recent OAE in the Cretaceous 94 mya when the Atlantic Ocean opened up. Patterns of global oceanic circulation oxygenating the deep ocean basins became established coinciding with a period of teleost diversification and appearance of the Acanthopterygii. Within the Actinopterygii, there is a trend for greater invasion of the deep sea by the lower taxa in accordance with the Andriashev paradigm. Here, 31 deep-sea families of Actinopterygii were identified with mean maximum depth >1000 m and with >10 species. Those with most of their constituent species living shallower than 1000 m are proposed as invasive, with extinctions in the deep being continuously balanced by export of species from shallow seas. Specialized families with most species deeper than 1000 m are termed deep-sea endemics in this study; these appear to persist in the deep by virtue of global distribution enabling recovery from regional extinctions. Deep-sea invasive families such as Ophidiidae and Liparidae make the greatest contribution to fish fauna at depths >6000 m.

Keywords: Actinopterygii, Chondrichthyes, Cretaceous, evolution, global anoxic event, Myxini

INTRODUCTION

Recent research on the origins of life on Earth increasingly favours the deep sea as the most likely site of the transition from geochemistry to life, with alkaline hydrothermal vents providing optimal conditions for this step (Lane & Martin, 2012). This is in contrast to the azoic hypothesis of Forbes (1844) who proposed that at depths >550 m the oceans are devoid of life. Despite this assertion, it is likely that from occasional accidental catches, strandings and carcasses floating to the surface, humans have long been aware that the oceans may harbour a deep-sea fish fauna. Working in the Mediterranean Sea, Risso (1810) provided one of the first scientific accounts of deep-sea fish species. He describes common mora Gadus moro, now known as Mora moro (Risso 1810), as very common at great depths in the Sea of Nice with very tender white flesh and good flavour. He observed depth zonation with species including chimaeras and Risso's smooth-head Alepocephalus rostratus Risso 1820 occurring at the greatest depths and lings, whitings and Phycidae at shallower depths (Risso, 1826). His descriptions are reiterated in the English language edition of the Universal Geography of Malte-Brun (1827). In 1833, Lowe began publishing a series of papers with descriptions of fishes found around the island of Madeira in the north-east Atlantic Ocean including black scabbard fish Aphanopus carbo Lowe 1839 and gives an account of how fishermen retrieve wreckfish Polyprion americanus (Bloch & Schneider 1801) from 550 to 730 m depth using baited lines (Lowe, 1843–1860). It is therefore surprising that some years later Forbes (1844) proposed the azoic hypothesis but this was based on the analysis of samples of benthic invertebrates dredged from the Aegean Sea. Anderson & Rice (2006) point out that there was substantial evidence before 1844 of invertebrate life at great depths in the oceans that appears to have been simply ignored by Forbes and some of his contemporaries.

There is no doubt that major advances in understanding of deep-sea fishes were made by Günther (1887) through the study of samples collected during the circumnavigation of the globe by the HMS Challenger (1873–1876) and associated expeditions that sampled depths to 2900 fathoms (ftm; 5300 m). The Challenger expedition finally refuted the azoic hypothesis demonstrating that life occurs even at great depths in the oceans. A total of 385 fish species were found at depths >100 ftm (183 m) but Günther only recognized 230 species found at depths >550 m as truly deep-sea species. Numbers of species and individuals were found to decrease with depth; Macrouridae being the most abundant followed by Ophidiidae and Gadidae. In his chapter on deep-sea fishes, Günther (1880) wrote ‘the fish fauna of the deep sea is composed chiefly of forms or modifications of forms we find represented at the surface…’. He concluded that 2750 ftm (5030 m) must be accepted as a depth at which fishes undoubtedly do live but the deepest species referred to in his work were almost certainly caught at shallower depths during ascent of the dredge to the surface. Since that time, cumulative sampling effort has demonstrated that fishes occur throughout the abyssal regions of the world's oceans down to over 6000 m depth (Merrett & Haedrich, 1997). In the 1950s, the expeditions by the Galathea (1950–1952) from Denmark and the Vityaz (1953–1957) from Russia undertook systematic sampling at depths >6000 m in hadal trenches of the Pacific Ocean. They found liparids, Notoliparis kermadecensis (Nielsen 1964) at 6660–6770 m depth in the Kermadec Trench in the south-west Pacific Ocean and Pseudoliparis amblystomopsis (Andriashev 1955) at 7230–7579 m in the Kuril-Kamchatka and Japan trenches of the north-west Pacific Ocean (Nielsen, 1964; Fujii et al., 2010). The deepest fish recorded to date is Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977, retrieved in 1970 from 8370 m depth in the Puerto Rico Trench. By the first decade of the 21st century, 3356 species of deep-sea fishes had been described, comprising 2081 bathydemersal and 1275 bathypelagic species. Extrapolating trends of species discovery, Mora et al. (2008) estimated that 1638 bathydemersal and 395 bathypelagic species remain to be discovered giving an expected total deep-sea ichthyofauna of 5389 species.

Woodward (1898) considered the origin of deep-sea fishes and argued that the evolutionary struggle for existence is most intense along the shore-line and that fresh waters and deep sea can be regarded as refuges into which less competitive primitive taxa have retreated. In Cretaceous chalk deposits, he identified fossils very similar to modern deep-sea fishes such as Sardinius now assigned to the Myctophiformes (Sepkoski, 2002) and Echidnocephalus, a halosaur. Thus, morphologically distinguishable deep water types evolved quite soon after the appearance of the first teleosts in the fossil record. He concludes that colonization of the deep sea by fishes has been a gradual process from Cretaceous times to the present day with a succession of new taxa moving deeper from the shallow seas in which they first arose. Andriashev (1953) divided the deep-sea fish fauna into ancient (or true) deep-water forms and secondary deep-water forms. The former correspond to the early deep-sea fishes belonging to lower phylogenetic groups such as Clupeiformes, Anguiliformes and Gadiformes and are characterized by world-wide distribution, specialized morphology and occupation of the greatest depths in the oceans. He includes Holocephali and Selachii in the ancient group. The secondary deep-water forms belong to the more recent teleost taxa, mainly Perciformes and the rays. His thinking was influenced by studies of the Arctic Ocean. He noted that relatively warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean, south of the Wyville Thompson Ridge, are populated by the ancient deep-water ichthyofauna, whereas these species are absent in cold waters to the north where secondary deep-water species derived from adjacent shelf areas are prevalent.

Thus, although life may have originated in the deep sea, colonization of the deep sea by fishes appears to have been through a process of diversification from shallow waters. Present day patterns of distribution of fishes are likely to reflect this history. Priede et al. (2006) pointed out that the Class Chondrichthyes is largely absent from abyssal depths >3000 m, whereas members of the Class Actinopterygii are found down to over 8000 m. In this paper, the depth distribution patterns of the modern fishes are examined and these are interpreted in relation to the evolution of deep-sea fishes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for depths of occurrence and maximum lengths were obtained for all marine species listed in fishbase.org (Froese & Pauly, 2013). This yielded entries for 16 307 species with records of maximum depths for 11 952 species. Depth data tend to be missing for shallow-water species for which depth is not regarded as a significant environmental variable. Data were sorted taxonomically and Petromyzontiformes (the few marine representatives are all anadromous), Pristiformes (shallow-water estuarine and freshwater habitats), Coelocanthiformes (Class Sarcopterygii, two living species, cave-dwelling, maximum depth 700 m) and Cyprinodontiformes (freshwater order with a few shallow-water marine representatives) were excluded from the analysis. The analysis was based on the maximum depth recorded for each species which is not representative of the typical depth at which most individuals of a species are likely to be found. Maximum depth, however, has the advantage that it has been recorded for most species and is an unequivocal single number. Caution is required when fishes have been captured using non-closing tow nets as specimens may have entered the net at any stage during its ascent often from great depths. Maximum depths over 6000 m were checked against the review by Fujii et al. (2010). Records were considered suspect if the depth was much deeper than typical for the species or group of species and where depth recorded was the maximum reached by gear that traversed a wide depth range and the specimen could have been captured at much shallower depths as in the case of a non-closing net. Some instances in which the depth recorded was the bottom sounding over which a pelagic net was towed were corrected to the actual depth of the net. For analysis of depth distributions, data were clustered in 500 m depth strata, 0–499, 500–999, 1000–1499 m et seq.

RESULTS

COMPARISON OF CLASSES MYXINI, CHONDRICHTHYES AND ACTINOPTERYGII

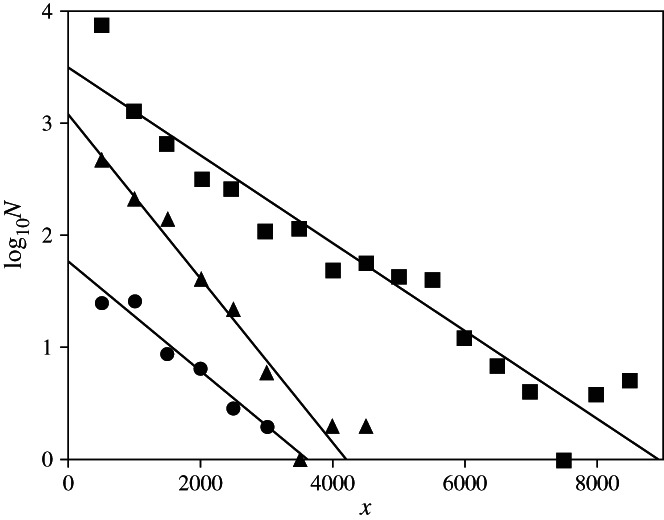

There was an overall trend of logarithmic decrease in species number with depth described by the fitted regression equation: all marine fish species log10N = −0·000422x + 3·610000 (r2 = 0·948), where N is the number of species maximum depths per 500 m depth stratum and x is the depth (m). Similar trends were seen for the individual classes (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

The relationship between log10N (N = number of species within a 500 m depth stratum) and depth (x) for three classes of fishes with fitted regression lines: Myxini ( ) log10N = −0·000488x + 1·760000 (r2 = 0·965), Chondricthyes (

) log10N = −0·000488x + 1·760000 (r2 = 0·965), Chondricthyes ( ) log10N = −0·000731x + 3·070000 (r2 = 0·954) and Actinopterygii (

) log10N = −0·000731x + 3·070000 (r2 = 0·954) and Actinopterygii ( ) log10N = −0·000413x + 3·550000 (r2 = 0·944).

) log10N = −0·000413x + 3·550000 (r2 = 0·944).

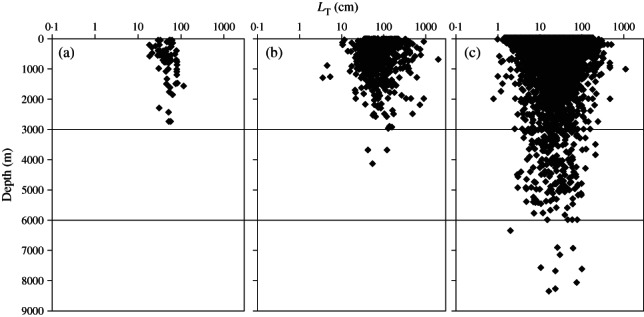

The global database contains records for 78 species of Myxini with data for 74 of these with a mean ± s.d. maximum depth of 795 ± 647 m. Two species of hagfishes were recorded at the maximum depth for this class with 2743 m, black hagfish Eptatretus deani (Evermann & Goldsborough 1907) and Guadalupe hagfish Eptatretus fritzi Wisner & McMillan 1990 (Fig. 2 and Table1). Number of species decreased with depth from 26 species found at shallower depths than 500 m, 27 species at 500–999 m and two species found deeper than 2500 m. The mean ± s.d. maximum total length (LT) was 51·2 ±18·5 cm with no obvious change in size with depth (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Scatter plots of species' maximum depth of occurrence and maximum total length (LT) for three classes of fishes: (a) Myxini, (b) Chondrichthyes and (c) Actinopterygii.

Table 1.

List of orders of fishes with statistics for maximum depths of occurrence. Orders are numbered in sequence of appearance in FishBase (Froese & Pauly, 2013). Statistics are given for the maximum depths

| Maximum depths (m) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Andriashev (1953) | Order | n | Mean | s.d. | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Myxni | Ancient | Myxini | 1 | Myxiniformes | 74 | 795 | 647 | 40 | 2743 |

| Chondrichthyes | Holocephali | 2 | Chimaeriformes | 45 | 1168 | 665 | 116 | 3000 | |

| Selachii | 3 | Hexanchiformes | 6 | 1273 | 725 | 570 | 2500 | ||

| 4 | Heterodontiformes | 9 | 132 | 97 | 37 | 275 | |||

| 5 | Orectolobiformes | 33 | 109 | 127 | 3 | 700 | |||

| 6 | Lamniformes | 15 | 856 | 568 | 191 | 2000 | |||

| 7 | Carcharhiniformes | 224 | 560 | 531 | 4 | 4000 | |||

| 8 | Squaliformes | 124 | 985 | 622 | 100 | 3700 | |||

| 9 | Pristiophoriformes | 7 | 473 | 260 | 165 | 1000 | |||

| 10 | Squatiniformes | 18 | 368 | 286 | 100 | 1390 | |||

| Secondary | Batoidea | 11 | Torpediniformes | 46 | 310 | 291 | 17 | 1153 | |

| 12 | Rajiformes | 385 | 598 | 612 | 6 | 4156 | |||

| Actinopterygii | Ancient | Lower Teleosts | 13 | Elopiformes | 1 | 50 | 50 | 50 | |

| 14 | Albuliformes | 4 | 419 | 434 | 84 | 1000 | |||

| 15 | Notacanthiformes | 27 | 2045 | 1112 | 706 | 5029 | |||

| 16 | Anguilliformes | 590 | 463 | 805 | 1 | 6000 | |||

| 17 | Saccopharyngiformes | 23 | 2765 | 1635 | 350 | 5800 | |||

| 18 | Clupeiformes | 163 | 67 | 71 | 2 | 450 | |||

| 19 | Gonorynchiformes | 5 | 375 | 481 | 100 | 1233 | |||

| 20 | Siluriformes | 20 | 45 | 29 | 5 | 120 | |||

| 21 | Osmeriformes | 203 | 1654 | 1139 | 70 | 5850 | |||

| 22 | Stomiiformes | 329 | 1308 | 1197 | 50 | 5301 | |||

| 23 | Ateleopodiformes | 10 | 675 | 234 | 494 | 1281 | |||

| 24 | Aulopiformes | 208 | 1184 | 1399 | 6 | 5900 | |||

| 25 | Myctophiformes | 210 | 1096 | 867 | 90 | 6000 | |||

| 26 | Lampriformes | 14 | 558 | 359 | 90 | 1200 | |||

| 27 | Polymixiiformes | 10 | 530 | 173 | 250 | 770 | |||

| Paracanthopterygii | 28 | Gadiformes | 562 | 1139 | 937 | 10 | 6945 | ||

| 29 | Ophidiiformes | 442 | 1139 | 1602 | 1 | 8370 | |||

| 30 | Batrachoidiformes | 32 | 117 | 129 | 3 | 600 | |||

| 31 | Lophiiformes | 297 | 1071 | 950 | 3 | 6370 | |||

| Secondary | Acanthopterygii | 32 | Gobiesociformes | 58 | 49 | 77 | 0 | 348 | |

| 33 | Atheriniformes | 12 | 10 | 12 | 1 | 39 | |||

| 34 | Beloniformes | 47 | 20 | 32 | 1 | 230 | |||

| 35 | Stephanoberyciformes | 59 | 2043 | 1367 | 200 | 5397 | |||

| 36 | Beryciformes | 140 | 389 | 582 | 3 | 4992 | |||

| 37 | Cetomimiformes | 28 | 2285 | 1359 | 200 | 6200 | |||

| 38 | Zeiformes | 32 | 827 | 444 | 200 | 1900 | |||

| 39 | Gasterosteiformes | 6 | 108 | 93 | 30 | 291 | |||

| 40 | Syngnathiformes | 190 | 67 | 125 | 1 | 1000 | |||

| 41 | Scorpaeniformes | 1238 | 631 | 869 | 1 | 7703 | |||

| 42 | Perciformes | 5206 | 200 | 460 | 0 | 5691 | |||

| 43 | Pleuronectiformes | 542 | 280 | 365 | 1 | 3210 | |||

| 44 | Tetraodontiformes | 253 | 152 | 235 | 5 | 2000 | |||

| 45 | Mugiliformes | 3 | 10 | 9 | 4 | 20 | |||

For the Chondrichthyes, 1141 species records were available with maximum depth records for 912 species. The deepest species was Bigelow's ray Rajella bigelowi (Stehmann 1978) recorded at 4156 m. More than 50% of species (475 records) occurred at depths <500 m with a mean ± s.d. maximum depth of 636 ± 608 m. The range of LT was greatest at shallower depths (Fig. 2) and overall mean ± s.d. maximum LT was 108·5 ± 119·3 cm.

For the Actinopterygii, there were 15 085 species, with maximum depth data for 10 965 of these. A total of 72% of species were recorded at depths shallower than 500 m but the distribution extends to 8370 m. The record for A. galatheae is the deepest known occurrence (Fig. 2). The mean ± s.d. maximum depth was 497·7 ± 879·6 m. There was no trend of change of fish size with depth and mean ± s.d. maximum LT was 33·4 ± 47·8 cm with the widest size range occurring at shallowest depths.

THE CHONDRICHTHYES

Subclass Holocephali

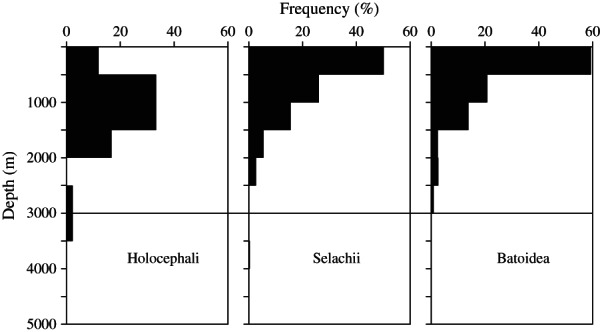

The single order of Holocephali contained 50 species with maximum depth records for 45 species. Five species had maximum depths <500 m and 64% of species records are between 500 and 1500 m (Fig. 3). The mean ± s.d. maximum depth was 1168 ± 657 m and the deepest species was the smalleyed rabbitfish Hydrolagus affinis (de Brito Capello 1868) recorded at 3000 m depth.

Fig 3.

Chondrichthyes. The depth-frequency distributions of three taxa, subclass Holocephali, subdivision Selachii and subdivision Batoidea. The horizontal line at 3000 m depth delineates the upper boundary of the abyss from which Chondrichthyes are largely absent (Priede et al., 2006).

Subclass Elasmobranchii, subdivision Selachii (sharks)

The Selachii comprises eight families (Table1) with a total of 504 species and 436 records of maximum depth of occurrence. Depths <500 m accounted for 49·9% of species and there was a significant decrease in species number with depth (Fig. 3): log10N = −0·000687x + 2·6700 (r2 = 0·880). The two deepest species were the cookie-cutter shark Isistius brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard 1824) and the Portuguese dogfish Centroscymnus coelolepis Barbosa du Bocage & de Brito Capello 1864, both recorded at 3700 m. The mean ± s.d. depth was 641 ± 569 m.

Subclass Elasmobranchii, subdivision Batoidea (rays)

The Batoidea comprises 587 species from two orders (Table1) with a total of 431 depth records. A total of 59·3% of species records were for depths <500 m and the mean ± s.d. maximum depth of occurrence was 568 ± 592 m. The deepest species in the order Torpediniformes was the New Zealand torpedo Torpedo fairchildi Hutton 1872 recorded at 1153 m and the deepest Rajiform species was R. bigelowi already referred to as the deepest of the Chondrichthyes at 4156 m. There was a significant decrease in species number with depth: log10N = −0·000605x + 2·550000 (r2 = 0·951).

ACTINOPTERYGII

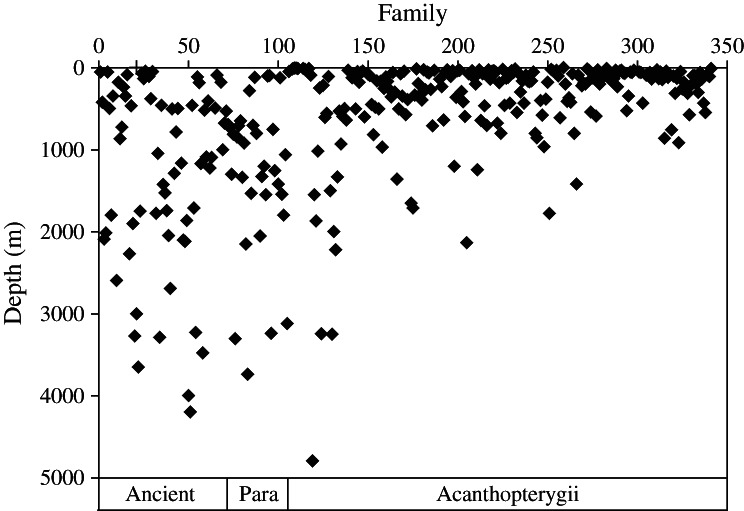

The Actinopterygii comprise 33 orders arranged in the phylogenetic sequence shown in Table1. The sequence from FishBase was used, which is based on a preliminary phylogeny, ranking species according to the presumed age of their common ancestor at least to their order level and within order and family wherever possible (Preikshot et al., 2000). Within each genus, species are ranked alphabetically. The relationship between maximum depth of occurrence and species rank is shown in Fig. 4. Whilst most species of Actinopterygii occur shallower than 500 m, the vertical linear clusters of points indicate taxa that have extended their range into the deep sea beyond 1000 m depth. There is a general trend that these and the maximum depths attained both decrease with increase in phylogenetic rank number. This is reflected in the linear fitted trend line indicating a decline in species depth: y = −0·0711x + 1104·0000 (r2 = 0·125), where y is depth in m and x is species taxonomic rank number. Although the correlation coefficient is low (i.e. there are other explanatory variables), the very large sample size (10 695) makes the effect of phylogeny highly significant (P < 0·001). It is interesting to note that the trend is also significant within the Acanthopterygii.

Fig 4.

Scatterplot of Actinopterygii species' maximum depth of occurrence in relation to phylogenetic rank in FishBase with a linear trend line fitted to the data: y = −0·0711x + 1103·6000 (r2 = 0·125).

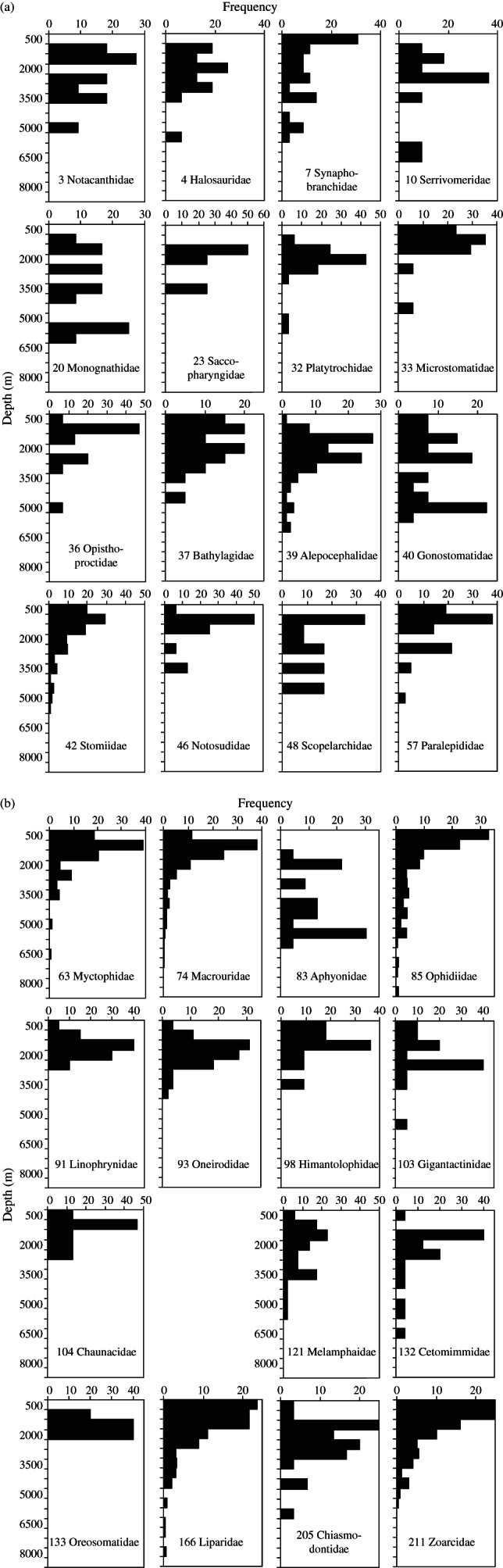

Grouping the data into 341 families, the mean depth of occurrence by family shows the same trend of decrease in depth from the ancient to advanced taxa (Fig. 5). To identify the most important deep-sea families of Actinopterygii, all families with a mean maximum depth of occurrence >1000 m were selected. Of these, 31 families had 10 or more species and are listed in Table2. The ancient or lower teleost orders contribute 17 families, the Paracanthopterygii eight and the Acanthopterygii contribute six families. Lower teleost families, however, have fewer species so the contributions to the deep-sea ichthyofauna were more or less equal, with lower teleosts of 953 species, Paracanthopterygii 824 and Acanthopterygii of 803 species. Mean maximum depths were 1815, 1695 and 1693 m, respectively.

Fig 5.

Mean maximum depth of occurrence by actinopterygian family in relation to phylogenetic rank according the FishBase.

Table 2.

List of deep-sea actinopterygian families with mean maximum depth >1000 m and with >10 species. Numbering (N) is in the order of listing in FishBase (Froese & Pauly, 2013). Habitat is the predominant type recorded in FishBase. Constants for the regression equation fitted to the species and depth data are given in the last three columns

| Depth (m) | Log10 species regression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | N | Family | Spp. | Maximum | Mean | Habitat | Slope | k | r2 | |

| Lower Teleosts | Notacanthiformes | 3 | Notacanthidae | 11 | 4560 | 2092 | Demersal | −0·000094 | 0·488 | 0·501 |

| Notacanthiformes | 4 | Halosauridae | 16 | 5029 | 2013 | Pelagic | −0·000115 | 0·620 | 0·531 | |

| Anguilliformes | 7 | Synaphobranchidae | 38 | 5440 | 1798 | Demersal | −0·000135 | 0·829 | 0·450 | |

| Anguilliformes | 10 | Serrivomeridae | 11 | 6000 | 2595 | Pelagic | −0·000036 | 0·246 | 0·107 | |

| Saccopharyngiformes | 20 | Monognathidae | 15 | 5800 | 3274 | Pelagic | 0·000007 | 0·174 | 0·005 | |

| Saccopharyngiformes | 23 | Saccopharyngidae | 10 | 3000 | 1751 | Pelagic | −0·000116 | 0·672 | 0·481 | |

| Osmeriformes | 32 | Platytroctidae | 39 | 5393 | 1776 | Pelagic | −0·000185 | 0·987 | 0·423 | |

| Osmeriformes | 33 | Microstomatidae | 19 | 4145 | 1044 | Pelagic | −0·000203 | 0·822 | 0·697 | |

| Osmeriformes | 36 | Opisthoproctidae | 19 | 4750 | 1424 | Pelagic | −0·000087 | 0·466 | 0·170 | |

| Osmeriformes | 37 | Bathylagidae | 22 | 4000 | 1526 | Pelagic | −0·000144 | 0·677 | 0·629 | |

| Osmeriformes | 39 | Alepocephalidae | 94 | 5850 | 2048 | Demersal | −0·000136 | 1·047 | 0·234 | |

| Stomiiformes | 40 | Gonostomatidae | 31 | 5301 | 2692 | Pelagic | −0·000027 | 0·440 | 0·033 | |

| Stomiiformes | 42 | Stomiidae | 285 | 5087 | 1290 | Pelagic | −0·000303 | 1·939 | 0·867 | |

| Aulopiformes | 46 | Notosudidae | 17 | 3000 | 1161 | Pelagic | −0·000067 | 0·483 | 0·043 | |

| Aulopiformes | 48 | Scopelarchidae | 18 | 4740 | 2116 | Pelagic | 0·000000 | 0·251 | 0·000 | |

| Aulopiformes | 57 | Paralepididae | 59 | 4750 | 1168 | Pelagic | −0·000237 | 1·243 | 0·795 | |

| Myctophiformes | 63 | Myctophidae | 249 | 6000 | 1092 | Pelagic | −0·000306 | 1·902 | 0·890 | |

| Paracanthopterygii | Gadiformes | 74 | Macrouridae | 398 | 6945 | 1299 | Demersal | −0·000335 | 2·176 | 0·929 |

| Ophidiiformes | 83 | Aphyonidae | 23 | 5610 | 3741 | Demersal | −0·000001 | 0·354 | 0·000 | |

| Ophidiiformes | 85 | Ophidiidae | 249 | 8370 | 1532 | Demersal | −0·000208 | 1·721 | 0·830 | |

| Lophiiformes | 91 | Linophrynidae | 29 | 2250 | 1328 | Pelagic | 0·000181 | 0·221 | 0·154 | |

| Lophiiformes | 93 | Oneirodidae | 65 | 3600 | 1550 | Pelagic | −0·000178 | 1·035 | 0·215 | |

| Lophiiformes | 98 | Himantolophidae | 21 | 3000 | 1257 | Pelagic | −0·000146 | 0·469 | 0·413 | |

| Lophiiformes | 103 | Gigantactinidae | 23 | 5300 | 1796 | Pelagic | −0·000086 | 0·473 | 0·163 | |

| Lophiiformes | 104 | Chaunacidae | 16 | 2200 | 1062 | Demersal | −0·000109 | 0·573 | 0·125 | |

| Acanthopterygii | Stephanoberyciformes | 121 | Melamphaidae | 61 | 5320 | 1870 | Pelagic | −0·000196 | 1·089 | 0·559 |

| Cetomimiformes | 132 | Cetomimidae | 30 | 6200 | 2219 | Pelagic | −0·000100 | 0·558 | 0·258 | |

| Zeiformes | 133 | Oreosomatidae | 10 | 1900 | 1330 | Pelagic | 0·000301 | 0·050 | 0·750 | |

| Scorpaeniformes | 166 | Liparidae | 382 | 7703 | 1359 | Demersal | −0·000283 | 2·127 | 0·929 | |

| Perciformes | 205 | Chiasmodontidae | 32 | 5691 | 2136 | Pelagic | −0·000043 | 0·486 | 0·036 | |

| Perciformes | 211 | Zoarcidae | 288 | 5320 | 1243 | Demersal | −0·000359 | 2·151 | 0·924 | |

Spp., the number of species per family listed in FishBase.

The deepest species within the lower teleosts was the eel Serrivomer brevidentatus Roule & Bertin 1929 recorded from 6000 m. Abyssobrotula galatheae (Ophidiidae), the world's deepest fish at 8370 m, belongs to the Paracanthopterygii and the deepest acanthopterygian was the liparid, P. amblystomopsis, found at 7703 m (Fujii et al., 2010).

The depth frequency distributions of the 31 deep-sea families are shown in Fig. 6. Regression equations of the form log10N = mx + k, have been fitted to the distributions, where N is the number of species within the depth interval, m is the slope (rate of change in species number with depth), k is a constant (log10 number of species at zero depth) and x is depth (m). These values for each family are given in Table2. Families such as the Liparidae (166) with slope values <−0·0003 and r2 > 0·8 have maximum species numbers at shallow depths and a good fit to the general model of logarithmic decrease in species number with depth. These can be regarded as deep-sea invasive families. Families such as the alepocephalids (39) with a peak in numbers at depths below 1000 m show a poor fit to the model and have slope values that are positive (Linophrynidae, 91) or >−0·0001. These can be regarded as deep-sea endemic families that have either lost their presumed shallow-dwelling family members through extinction or have simply diverged so much from their shallow-water ancestors as to form a new family. Examining r2 and slope values in Table2, it is evident that all the three divisions of teleosts, lower, Paracanthopterygii and Acanthopterygii, contribute families across the spectrum between invasive and endemic. Correlations between family number and slope and r2 in Table2 are both insignificant (r2 = 0·0046 and 0·0259, respectively) indicating that taxonomic position is no predictor of whether a deep-sea family is endemic or invasive. For several of the families designated as invasive by this analysis, in Macrouridae, Stomiidae and Myctophidae, the peak of distribution of maximum depths lies at continental slope or mesopelagic depths of 500–1000 m rather than between the surface and 500 m.

Fig 6.

Depth-frequency distributions of fishes in the 31 deep-sea actinopterygian families ranked by order (N) given in Table2, i.e. families with a mean maximum depth of occurrence >1000 m and >10 species. (a) The lower families Notacanthidae to Paralepididae, (b) Myctophidae, Paracanthopterygii (Macrouridae to Chaunacidae) and the Acanthopterygii (Melamphaidae to Zoarcidae).

DISCUSSION

There is a clear global trend of logarithmic decrease in number of fish species with depth. The slope constant of the relationship between log10n and depth (−0·000422) predicts a 2·6 fold decrease in species per km increase in depth. This is very similar to estimates of rate of change in pelagic (Roe, 1988) and benthic biomass (Rex et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2010) with depth which show an overall mean slope of −0·00043 (Table3). Priede et al. (2013) show that pelagic and benthic biomass are linked to one another and are both determined by the availability of export food energy from the surface (Smith et al., 2009). With increasing distance from the primary producers in the euphotic zone, less biomass can be supported, fish populations become sparser and it appears that global fish biodiversity follows this depth-related energy constraint. Therefore, a primary hypothesis is proposed that the distribution of fish species with depth is governed by availability of energy.

Table 3.

Trends of decrease in deep-sea pelagic and benthic biomass. List of slopes (s) in the general equation: log10B = sx + k, where x is the depth (m) and k is a constant

The slopes of the regression lines for Myxini and Actinopterygii, 0·000488 and 0·000401 respectively, follow essentially the same energy-limited slope as observed in the entire global ichthyofauna. Chondrichthyes, however, show a much steeper slope of 0·000731, with species number decreasing by a factor of 5·4 for every 1000 m depth increment indicating that this class is in some way deficient in its ability to colonize the deep sea. Priede et al. (2006) suggested that Chondrichthyes might be limited by high energy requirements for buoyancy from an oil-rich liver. Such energy-limitation, however, would imply a slope closer to that for other classes of fishes. There may be other physiological limitations such as the need to use trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) for maintaining osmotic balance and to confer pressure tolerance on vital proteins (Yancey & Siebenaller, 1999). Alternatively, there may be reproductive limitations or a combination of factors. Many deep-sea teleost species such as macrourids (Marshall, 1965) produce buoyant eggs so that planktivorous larvae develop in the surface layers of the ocean where copious food is available. Such a strategy is not available to Chondrichthyes owing to their large egg size and low fecundity. Planktotrophic development is only possible if inevitable high mortality is compensated for by high fecundity. Chondrichthyes invest all their reproductive effort in a few eggs with enough yolk to support direct development. Body size may also be a factor, mean maximum body LT for the Chondrichthyes (108·5 cm) is much larger than for Actinopterygii (33·4 cm), and may be above the optimal size for survival at abyssal depths (Collins et al., 2005).

Comparing the three classes, the depth attained [Myxini (2743 m), Chondrichthyes (4156 m) and Actinopterygii (8370 m)] was correlated with the number of species 78, 1141 and 15 085 in the respective taxa. In all three classes, there is a maximum diversity at shallow depths suggesting that shallow seas act as centres of speciation. Habitat heterogeneity and intense competition in upper slope and shelf seas are likely to create possibilities for fractioning of populations and evolution of new species (Bowen et al., 2013), some of which may be relocated into the deep sea. The number of species moving into the deep sea would then be determined by the total number of shallow-water species and their speciation rate. A secondary hypothesis is proposed that the slope of the species–depth relationship may then be determined by the balance between colonization and extinction rates in the deep sea. Thus, the Actinopterygii reach the greatest depths in the ocean (Fig. 2) by virtue of their high species number and presumed high speciation rate. Theoretically, if Myxini were as numerous as the Actinopterygii they would attain the same depth. Chondrichthyes may be disadvantaged by an intrinsically low speciation rate or high extinction rate owing to physiological limitations. It is notable that in all three classes (Fig. 2) the length frequency distribution is log-normal (Froese, 2006) and that fishes at the greatest depths tend towards mean size.

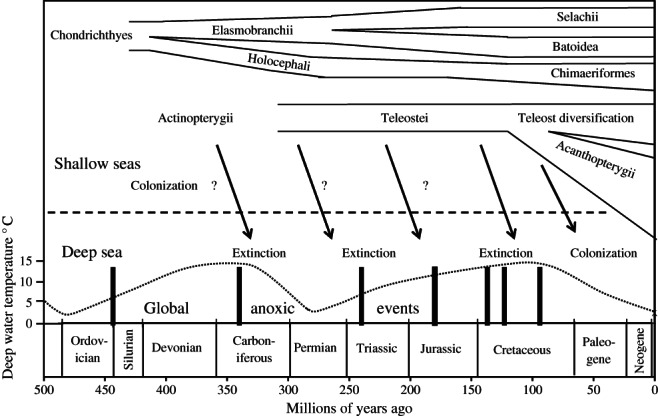

The relationship between evolution of fishes and the history of the oceans is summarized in Fig. 7. The deep ocean is prone to stagnation, if no water in the upper 1000 m becomes sufficiently dense to displace deeper water then the stratification is stable and the deep waters tend to become anoxic (Schopf, 1980). A modern example is the Black Sea (Wilkin et al., 1997) which is anoxic and devoid of metazoan life beyond a few hundred m depth. Throughout the Earth's history, there has been a series of global ocean anoxic events, when it is presumed that all conventional deep-sea metazoan life must have been extinguished (Takashima et al., 2006). There is a general consensus that the modern deep-sea benthic invertebrate fauna has originated from shallow waters following elimination of ancient deep-sea faunas by mass extinction events during the Jurassic and Cretaceous anoxic periods (Rex & Etter, 2010). Nevertheless, Thuy et al. (2012) report discovery of fossil echinoderm assemblages from 114 mya at 1000–1500 m paleodepth in the north-west Atlantic Ocean with a modern composition indicating possible survival through the most recent Cretaceous global oceanic anoxic event known as OAE2, Cenomanian–Turonian (Yilmaz et al., 2010) c. 94–96 mya. Raup & Sepkoski (1986) estimate that this event resulted in extinction of 50% of marine genera and 15% of families; even mass extinction events do not result in total loss of fauna. There is no doubt that deep-sea families would be particularly vulnerable to OAEs. In addition to global anoxic events, regional anoxia occurs at a higher frequency. For example, on the floor of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, sapropel layers rich in organic matter indicate deep-water anoxic events at intervals of tens of thousands of years. During the Messinian salinity crisis 5·96 to 5·33 mya, the Mediterranean Sea basin dried out, reducing sea level by 1500 m creating salt deposits and anoxic brine pools (Garcia-Castellanos & Villasen, 2011) totally eliminating the marine fauna until re-colonization when the sea re-filled (Garcia-Castellanos et al., 2009). An alternative to the stagnant ocean basin model is expansion of oxygen minimum layers creating regional anoxia in an otherwise oxic ocean above and below (Takashima et al., 2006). Such events have occurred in the eastern Pacific Ocean during the Miocene (10–20 mya) forming barriers to fish movement that have been implicated in speciation in the deep sea (White, 1987). Thus, whilst the deep sea is often perceived as a stable environment, on a geological time scale it has been a transitory habitat.

Fig 7.

The geological time scale and evolution of fishes.  indicate global anoxic events (after Takashima et al., 2006) when the deep sea is unlikely to have been habitable by fishes. Deep-sea bottom temperatures are indicated by the

indicate global anoxic events (after Takashima et al., 2006) when the deep sea is unlikely to have been habitable by fishes. Deep-sea bottom temperatures are indicated by the  and scale on the left (Schopf, 1980). Times of divergence of the major classes, subclasses and divisions of fishes are taken from recent literature.

and scale on the left (Schopf, 1980). Times of divergence of the major classes, subclasses and divisions of fishes are taken from recent literature.  indicate the probable pattern of colonization of the deep from shallow seas but with localized and global extinctions in the deep. ? indicate putative pre-Cretaceous colonisation for which there is no direct evidence.

indicate the probable pattern of colonization of the deep from shallow seas but with localized and global extinctions in the deep. ? indicate putative pre-Cretaceous colonisation for which there is no direct evidence.

Further changes have occurred associated with the process of break-up of the supercontinent Pangaea from c. 200 mya and the first opening up of the Atlantic Ocean c. 150 mya (Sheridan et al., 1982). Initially, the Atlantic Ocean consisted of separate northern and southern enclosed basins. Deep-water connections between the north and south Atlantic Ocean did not appear until 80 to 65 mya and essentially modern deep-water circulation was not established until 35 mya (Schopf, 1980). The depth of the ocean floor has also increased. During sea floor spreading, new oceanic crust is formed at a depth of c. 2600 m and as the hot basalt cools it contracts, increasing the ocean depth to over 5500 m after 70 million years. The Atlantic Ocean attained its current bathymetry c. 10 mya. Beyond 6000 m, the hadal zone is confined to oceanic trenches and troughs, the total area of which is <1% of the sea floor. A total of 37 hadal trenches and troughs have been identified, five in the Atlantic Ocean, four in the Indian Ocean and 28 around the Pacific Ocean rim (Jamieson et al., 2010). Trench formation is dependent on movement of tectonic plates; so this has been contemporary with movement of the continents into their current positions.

A characteristic feature of the modern deep-sea is that bottom water temperatures are low (typically 0–4° C); however, throughout earth history, there have been considerable fluctuations in bottom water temperature. Whilst surface temperature in tropical regions has been remarkably constant, 20–25° C, for over 700 million years, tropical bottom water temperature has oscillated between 15° C or more during warm periods in the Cambrian (500–600 mya), Devonian-Carboniferous (350 mya) and Cretaceous (100 mya), and 2° C during cold glacial periods in the Ordovician (450 mya), Permian (270 mya) and the present day (Schopf, 1980) (Fig. 7). In the North Atlantic Ocean, it is estimated that bottom water temperatures may have reached 20° C during the Cretaceous (Huber et al., 2002). Since that time, global deep waters have cooled to present-day values. Thus, during the initial period of colonization of the deep sea by modern fish taxa in the late Cretaceous, there would have been a small temperature gradient to overcome between the surface and the deep-sea floor. Deep water in the Mediterranean Sea and Red Sea remains at a temperature of 13–15° C as circulation is maintained by evaporation and sinking of warm saline water in contrast to oceanic deep-water formation by cooling (Schopf, 1980).

The major fish taxa originated long before the post-Cretaceous colonization of the deep sea, so their history in relation to palaeoceanography needs to be considered to understand present-day distributions. The origins of the hagfishes, Myxini, have been much debated Janvier (2010). It is now accepted that they are related to lampreys and other vertebrates but have undergone a process of degeneration from an anatomically more complex common ancestor (Heimberg et al., 2010). Fossil myxinids have been found in the late Carboniferous (Bardack, 1991) with a body form very similar to living species, indicating little change for over 300 million years and absence of new diversification. It is not possible to recognize deep-water specialists morphologically in the group, because all myxinids are anatomically very similar. The ability of myxinids to tolerate severe anoxia (Hansen & Sidell, 1983; Cox et al., 2011) suggests that they may have occupied the deep-sea ocean margins throughout their history with little evolutionary change in the face of advance and regression of deep-water oxygenation.

Molecular clock data (Licht et al., 2012) indicate that Holocephali diverged from the Elasmobranchs just over 400 mya near the beginning of the Devonian period, the so-called Age of Fishes. The Holocephali then diversified during the Jurassic, the Chimaeridae appearing c. 100 mya in the Cretaceous. For the modern Holocephali, the peak of distribution (Fig. 3) is between 500 and 1500 m depth suggesting this is a true deep-sea group of fishes. Molecular clock estimates show important speciation events after the last Cretaceous global OAE2: Rhinochimaera and Harriotta branch at 58 mya, Hydrolagus and Chimaera at 25–81 mya and Callorhincus species at 8–11 mya. It appears that whilst deep-sea Holocephali may be a truly ancient group there has been a considerable recent diversification. Studies on the physiology of the spotted ratfish Hydrolagus colliei (Lay & Bennett 1839) (Speers-Roesch et al., 2006) show that the energy metabolism pathways are very similar to those of elasmobranchs. Speers-Roesch & Treberg (2010) suggest that Holocephali and elasmobranchs have retained the metabolic organization that was present in the common ancestor of the Chondrichthyes over 400 mya. Despite their deeper distribution compared with other Chondrichthyes (Fig. 3), there is no evidence of distinctive physiological adaptations in the Holocephali.

The Selachii and Batoidea diverged from one another during the late Permian c. 260 mya. Modern orders of sharks and rays radiate from the Jurassic (160 mya) onwards to produce the present-day species, with >50% of species living at <500 m depth (Fig. 3). In the Selachii and Batoidea, the species-depth distribution fits the concept of recent colonization of the deep sea by species export from shallow seas.

The earliest actinopterygian fossil has been found in the mid-Devonian c. 380 mya and molecular clock data indicate that Teleostei appeared during the Carboniferous to early Permian, 333 to 285 mya (Near et al., 2012). This estimate is much earlier than the oldest known teleost fossils, elopomorphs and ostarophysians of the late Jurassic c. 180 mya. A major difficulty impeding interpretation of the early history of the Actinopterygii is the ‘teleost gap’, a lack of fossils from the mid-Carboniferous to early Triassic (Hurley et al., 2007; Near et al., 2012). The late Jurassic and early Cretaceous mark the onset of major diversification of the teleosts; the Acanthopterygii diverging c. 130 mya and many teleost taxa appearing during the Paleogene, which Near et al. (2012) propose should be known as the ‘Second Age of Fishes’. It is hypothesized that genome duplication triggered the origin of teleosts and their subsequent radiation. Santini et al. (2009) also detected an additional series of pulses of radiation notably 65 to 23 mya. They caution against ascribing these recent changes entirely to genetic mechanisms, pointing out that major environment changes, such as establishment of scleractinian coral reefs in tropical shallow habitats, continental drift, sea level fluctuations and oceanographic changes, all probably have had an effect. The time period since the Cretaceous OAE2, 94 mya, therefore is marked by cooling, reoxygenation and deepening of the abyssal ocean basins coinciding with an explosion of teleost diversification, particularly the Acanthopterygii, including some colonization of the deep sea. Myxini, Holocephali, early Elasmobranchs and Actinopterygii may have inhabited ancient deep seas from the end of the Devonian onwards when conditions were suitable, but continuous occupation through mass extinctions seems unlikely. All groups except the Myxini show important recent diversification.

Within the Actinopterygii, there is a trend that more primitive orders (in the terminology of Andriashev, 1955) are more likely to have deep-sea representatives (Figs 4 and 5). Passage of time has presumably given more opportunities to colonize the deep sea but absence of a thermocline in the Cretaceous ocean and lack of competition in the deep sea after the OAE2 extinctions may have been more conducive to deep-sea colonization than in the modern ocean. Interpretations, however, are affected by taxonomy. This study has followed the phylogenetic sequence in FishBase (Froese & Pauly, 2013) and has used the Paracanthopterygii as a convenient intermediate group between the ancient orders and the Acanthopterygii. It is doubtful, however, if it is a monophyletic (Nelson, 2006) and molecular phylogeny now breaks up the Paracanthopterygii placing Lophiiformes with the Tetraodontiformes amongst the most recent of Acanthopterygii (Near et al., 2012). Ophidiiformes and Batrachiformes remain together, but the Gadiformes and Zeiformes become sister groups just below the Myctophiformes (Table1). Following this revision, the Lophiiformes with quintessential highly specialized deep-sea species such as angler fishes of the superfamily Ceratioidea with their dwarf males are placed as very recent arrivals in the deep sea, contrary to the ideas of Andriashev (1955). Molecular clock data indicate divergence of the Lophiiformes at the end of the Cretaceous (66 mya) and Carnevale & Pietsch (2009) describe a fossil linophrynid from Miocene chalk deposits of southern California (10–20 mya). These revisions of positions of different orders are not sufficient to disrupt the general conclusions from Figs 3 and 4 that older orders have a larger proportion of species in the deep sea, but fish phyologeny is currently in a state of flux (Nelson, 2006). The Miocene beds of southern California harbour a rich assemblage of oceanic and deep-sea fishes including caristiids, lampridids, melamphaids, sternoptychids, myctophids and stomiids (Carnevale & Pietsch, 2009) indicating that by this time many features of the modern deep-sea ichthyofauna had become well established, contemporary with appearance of the first apes on land.

In this study, analysis of deep-sea families (Fig. 6) identified two types of depth-frequency distribution, invasive and deep-sea endemic. The invasive families (e.g. Synaphobranchidae, Ophidiidae and Liparidae) have most of their representatives in shallow seas with a tail of the distribution extending into the deep sea, whereas the deep-sea endemic families are those that have their centre of distribution at depths >1000 m and have few or no species living at shallow depths (e.g. Serrivomidae, Monognathidae, Alepocephalidae, Aphyonidae and Chiasmodontidae). It is hypothesized that in the invasive families, colonization from shallower waters replaces species that become extinct in the deep sea. Thus, the persistence of the taxon in the deep sea is by virtue of constant replenishment from above. Although identified as invasive families, the Myctophidae, Macrouridae and Zoarcidae have a deeper peak of depth distribution between 500 and 1000 m. The centre of speciation may be on the upper slope or in the mesopelagic with species exported upwards into shallow water as well as down towards the abyss.

It is paradoxical that the invasive families with most species in shallow seas are also the main contributors to the hadal ichthyofauna at depths >6000 m (Fujii et al., 2010). The hadal fauna is characterized by the presence of regionally endemic liparids. Thus, in the north-west Pacific Ocean, the Japan and Izu-Bonin trenches are populated by P. amblystomopsis (Andriashev, 1955), whereas south-west Pacific Kermadec and Tonga Trenches are populated by N. kermadecensis. It is likely that these are the results of independent speciation events. The four species of the genus Notoliparis are endemic to four different trench systems in the southern hemisphere indicating allopatric speciation in the deep sea and colonization by distinctive hadal forms from trench to trench. The hadal trenches and basins may be regarded as an archipelago of discrete habitats colonized in accordance with equilibrium theory of island biogeography (MacArthur & Wilson, 1963). The Ophidiid, A. galatheae, generally recognized as the world's deepest fish, is the extreme representative of an invasive family with >30% of species shallower than 500 m depth but with a significant tail of its depth distribution extending into the deep sea [Fig. 6(b)]. The Ophidiidae are a conspicuous component of the abyssal demersal ichthyofauna and it is not surprising that they are represented at hadal depths beyond 6000 m. In contrast to hadal liparids, which have been repeatedly seen from manned and unmanned submersibles and captured in traps (Fujii et al., 2010), there has been no further confirmation of hadal occurrence of A. galatheae since capture of the first specimen by trawl. As this is a demersal species, capture during ascent of the net through the water column appears unlikely, so the original record (Nielsen, 1977) cannot be rejected lightly. Whatever the true status of A. galatheae, the maximum depth limit for fishes appears to be c. 8000 m. Reported observation of flatfishes at the bottom of the Marianas Trench at c. 10 900 m depth during the dive of the bathyscaphe Trieste in 1960 is now regarded as erroneous (Jamieson & Yancey, 2012). There may be ultimate physiological limits to the depth attainable by fishes but also the environment of the trench beyond 8000 m depth is dominated by increasing numbers of lysianassoid amphipods that swarm around artificial food falls (Blankenship & Levin, 2007; Jamieson et al., 2009) possibly competitively excluding fishes or indeed preying upon them.

The deep-sea endemic families generally have highly modified body forms specialized to life in the deep sea. Many species are global in their distribution and in this way can recolonize in the event of regional extinction events in contrast to the invasive hadal liparids which must be vulnerable to extinction by events within particular trench systems. Furthermore, Howes (1991) points out that within the gadoids circumglobal distribution is characteristic of the more primitive taxa and the phylogenetic trend has been a process of colonization from oceanic to shelf regions; so the derived taxa occupy shallow seas, which is actually the reverse of the generally accepted trend. A remarkable example of potential for oceanic to shallow-water diversification is in the eels. Inoue et al. (2010) show that the freshwater eels Anguilla spp. are most closely related to mesopelagic eels of the families Nemichthyidae and Serrivomidae (deep-sea endemics in the classification of this study) that spawn in the open ocean. Anguilla japonica Temminck & Schlegel 1846 has been found to spawn at 220–230 m depth in the western North Pacific Ocean, a trait apparently retained from their oceanic pelagic ancestry (Chow et al., 2009).

Within the teleosts, analysis in this study confirmed the general proposition of Andriashev (1955) with a greater depth of occurrence in the more ancient taxa (Figs 4 and 5). The dichotomy between the ancient (specialized) and secondary (non-specialised) deep-water fishes, however, is becoming blurred by advances in taxonomy. The Acanthopterygii are dominated by a vast diversity of shallow-water species but nevertheless contribute significantly to the deep-sea ichthyofauna including several deep-sea endemic families [Fig. 6(b)]. Whilst the Holocephali can be regarded as ancient deep-water forms, there seems to be no reason to separate the Selachii as ancient and the Batoidea as secondary; they appear to have colonized the deep sea synchronously.

A problem that remains here is the analysis that is based on data for maximum depth of occurrence which are prone to error, particularly arising from uncertainty of depth of capture where the fishing gear has traversed a large bathymetric range. Camera vehicles equipped with depth sensors provide unambiguous evidence of the depth of living (Jamieson et al., 2009), although species identification must be confirmed by capture of specimens. A high threshold (1000 m) was also used to define deep-sea families. This has excluded some families which make an important contribution to the deep-sea ichthyofauna, such as the Moridae (mean maximum depth of 808 m) and Trachichthyidae (mean maximum depth of 602 m), which include important commercial species such as the blue antimora Antimora rostrata (Günther 1878) and orange roughy Hoplostethus atlanticus Collett 1889 respectively. In this study, the 500 m depth increments fail to resolve the detail of the mesopelagic and upper slope ichthyofaunas which are often zones of high biodiversity (Priede et al., 2010); this was outside the scope of the present investigation.

Whilst there is good evidence of colonization of the deep sea from the Cretaceous onwards, there is no direct evidence of deep-sea fish faunas during periods of potential colonization between anoxic events from the Devonian to Jurassic (Fig. 7). For invertebrates, Thuy et al. (2012) found fossils indicating localized survival of deep-sea echinoderms through the Cretaceous OAE2 leading them to propose the possibility of a more ancient origin for deep-sea fauna. Continuous survival of deep-sea lineages through multiple anoxic events seems unlikely for fishes whose data are consistent with continuing colonizations from shallow seas over the past 100 million years. The question of a pre-Cretaceous deep-sea ichthyofauna remains an enigma.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to numerous inspiring colleagues with whom we have worked on deep-sea fishes at sea and on shore. We especially acknowledge the invaluable work of FishBase staff and contributors. The work was supported by NERC grant: NE/ C512961/1 and is FIN contribution No. 132.

References

- Anderson TR. Rice T. Deserts on the sea floor: Edward Forbes and his azoic hypothesis for a lifeless deep ocean. Endeavour. 2006;30,:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.endeavour.2006.10.003. doi: 10.1016/j.endeavour.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriashev AP. Ancient Deep-Water and Secondary Deep-Water Fishes and their Importance in Zoogeographical Analysis. Notes of Special Problems in Ichthyology. 1953. Fish & Wildlife Service Translation Series 6. Moscow, Leningrad; Akademie.Nauk.SSSR. Ikhiol.Kom. [Translation by A. R. Gosline, Ichthyological Laboratory, Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. Washington DC: US National Museum]

- Andriashev AP. A new fish of the snailfish family (Pisces, Liparidae) found at a depth of more than 7 kilometers. Trudy Instituta Okeanologii im. P.P. Shirshova. 1955;12,:340–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bardack D. First fossil hagfish (Myxinoidea): a record from the Pennsylvanian of Illinois. Science. 1991;254,:701–703. doi: 10.1126/science.254.5032.701. . 10.1126/science.254.5032.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship LE. Levin LA. Extreme food webs: foraging strategies and diets of scavenging amphipods from the ocean's deepest 5 kilometers. Limnology and Oceanography. 2007;52,:1685–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen BW, Rocha LA, Toonen RJ, Karl SA the ToBo Laboratory. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2013;28,:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.018. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale G. Pietsch TW. The deep-sea anglerfish genus Acentrophryne (Teleostei, Ceratioidei, Linophrynidae) in the Miocene of California. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 2009;29,:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Chow S, Kurogi H, Mochioka N, Kaji S, Okazaki M. Tsukamoto K. Discovery of mature freshwater eels in the open ocean. Fisheries Science. 2009;75,:257–259. doi: 10.1007/s12562-008-0017-5. [Google Scholar]

- Collins MA, Bailey DM, Ruxton GD. Priede IG. Trends in body size across an environmental gradient: a differential response in scavenging and non-scavenging demersal deep-sea fish. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2005;272,:2051–2057. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GK, Sandblom E, Richards JG. Farrell AP. Anoxic survival of the Pacific hagfish (Eptatretus stoutii. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 2011;181,:361–371. doi: 10.1007/s00360-010-0532-4. 10.1007/s00360-010-0532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes E. Report on the Mollusca and Radiata of the Aegean Sea, and on their distribution, considered as bearing on geology. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. 1844;1843,:129–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Jamieson AJ, Solan M, Bagley PM. Priede IG. A large aggregation of liparids at 7703 m depth and a reappraisal of the abundance and diversity of hadal fish. BioScience. 2010;60,:506–515. [Google Scholar]

- Froese R. Cube law, condition factor, and weight-length relationships: history, meta-analysis and recommendations. Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 2006;22,:241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castellanos D. Villasen A. Messinian salinity crisis regulated by competing tectonics and erosion at the Gibraltar arc. Nature. 2011;480,:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nature10651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Castellanos D, Estrada F, Jiménez-Munt I, Gorini C, Fernàndez M, Vergés J. De Vicente R. Catastrophic flood of the Mediterranean after the Messinian Crisis. Nature. 2009;462,:778–781. doi: 10.1038/nature08555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther ACLG. An Introduction to the Study of Fishes. Edinburgh: A. and C. Black; 1880. [Google Scholar]

- Günther ACLG. Scientific Results of the Voyage of HMS Challenger during the Years 1873–76: XXII Zoology. 1887. Report on the deep-sea fishes collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76. In (Murray, J. ed.). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Available at https://archive.org/details/reportondeepseaf00gn.

- Hansen CA. Sidell BD. Atlantic hagfish cardiac-muscle metabolic basis of tolerance to anoxia. American Journal of Physiology. 1983;244,:R356–R362. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.244.3.R356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg AM, Cowper-Sallari R, Sémon M, Donoghue PCJ. Peterson KJ. MicroRNAs reveal the interrelationships of hagfish, lampreys, and gnathostomes and the nature of the ancestral vertebrate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107,:19379–19383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010350107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010350107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes GJ. Biogeography of gadoid fishes. Journal of Biogeography. 1991;18,:595–622. [Google Scholar]

- Huber BT, Norris RD. MacLeod KG. Deep-sea paleotemperature record of extreme warmth during the Cretaceous. Geology. 2002;30,:23–126. 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0123:DSPROE>2.0.CO;2. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley IA, Mueller RL, Dunn KA, Schmidt EJ, Friedman M, Ho RK, Prince VE, Yang Z, Thomas MG. Coates MI. A new time-scale for ray-finned fish evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2007;274,:489–498. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3749. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue JG, Miya M, Miller MJ, Sado T, Hanel R, Hatooka K, Aoyama J, Minegishi Y, Nishida M. Tsukamoto K. Deep-ocean origin of the freshwater eels. Biology Letters. 2010;6,:363–366. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson AJ. Yancey PH. On the validity of the Trieste flatfish; dispelling the myth. Biological Bulletin. 2012;222,:171–175. doi: 10.1086/BBLv222n3p171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson AJ, Fujii T, Solan M, Matsumoto AK, Bagley PM. Priede IG. Liparid and macrourid fishes of the hadal zone: in situ observations of activity and feeding behaviour. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2009;276,:1037–1045. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1670. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson AJ, Fujii T, Mayor DJ, Solan M. Priede IG. Hadal trenches: the ecology of the deepest places on Earth. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2010;25,:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janvier P. MicroRNAs revive old views about jawless vertebrate divergence and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107,:19137–19138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014583107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N. Martin WF. The origin of membrane bioenergetics. Cell. 2012;151,:1406–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licht M, Schmuecker K, Huelsen T, Hanel R, Bartsch P. Paeckert M. Contribution to the molecular and phylogenetic analysis of extant holocephalan fishes (Holocephali, Chimaeriformes) Organisms Diversity and Evolution. 2012;12,:421–432. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe RnT. A History of the Fishes of Madeira. 1843-1860. London: Van Voorst.

- Macarthur RH. Wilson EO. An equilibrium theory of insular zoogeography. Evolution. 1963;17,:373–387. [Google Scholar]

- Malte-Brun C. Universal Geography, or a Description of All Parts of the World, on a New Plan, According to the Great Natural Divisions of the Globe. Philadelphia, PA: A. Finley; 1827. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall NB. Systematic and biological studies of the macrourid fishes (Anacanthini — Teleostei) Deep-Sea Research. 1965;12,:299–322. [Google Scholar]

- Merrett NR. Haedrich RL. Deep-Sea Demersal Fish and Fisheries. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mora C, Tittensor DP. Myers RA. The completeness of taxonomic inventories for describing the global diversity and distribution of marine fishes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2008;275,:149–155. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near TJ, Eytan RI, Dornburg A, Kuhn KL, Moore JA, Davis MP, Wainwright PC, Friedman M. Smith WL. Resolution of ray-finned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109,:13698–13703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206625109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206625109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JS. Fishes of the World. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JG. Scientific Results of The Danish Deep-Sea Expedition Round the World 1950–52: 7. 1964. Fishes from depths exceeding 6000 meters. In (Wolff, T. ed.) pp. 113–124. Copenhagen: Danish Science Press Ltd. Available at http://www.zmuc.dk/inverweb/galathea/Pdf_filer/Volume_07/galathea-vol.07-pp_001-006.pdf.

- Nielsen JG. Abyssobrotula galatheae: Scientific Results of The Danish Deep-Sea Expedition Round the World 1950–52: 7. 1977. The deepest living fish: a new genus and species of oviparous ophidioids (Pisces, Brotulidae). In (Wolff, T. ed.) pp. 41–48. Copenhagen: Danish Science Press Ltd. Available at http://www.zmuc.dk/inverweb/galathea/Pdf_filer/Volume_14/galathea-vol.14-pp_041-048.pdf.

- Preikshot D, Froese R. Pauly D. The ORDERS table. In: Pauly D, editor; Froese R, editor. FishBase 2000: Concepts, Design and Data Sources. Los Banos: ICLARM; 2000. pp. 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Priede IG, Froese R, Bailey DM, Bergstad OA, Collins MA, Dyb JE, Henriques C, Jones EG. King N. The absence of sharks from abyssal regions of the world's oceans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2006;273,:1435–1441. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3461. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priede IG, Godbold JA, King NJ, Collins MA, Bailey DM. Gordon JDM. Deep-sea demersal fish species richness in the Porcupine Seabight, NE Atlantic Ocean: global and regional patterns. Marine Ecology. 2010;31,:247–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00330.x. [Google Scholar]

- Priede IG, Bergstad OA, Miller PI, Vecchione M, Gebruk A, Falkenhaug T, Billett DSM, Craig J, Dale AC, Shields MA, Sutton TT, Gooday AJ, Inall ME, Jones DAB, Martinez-Vicente V, Menezes GM, Niedzielski T, Tilstone GH, Sigurðsson Þ, Rothe N, Rogacheva A, Alt CHS, Brand T, Abell R, Brierley AS, Cousins NJ, Crockard D, Hoelzel AR, Høines Å, Letessier TB, Read JF, Shimmield T, Cox MJ, Galbraith JK, Gordon JDM, Horton T, Neat F. Lorance P. Does presence of a Mid Ocean Ridge enhance biomass and biodiversity? PLoS One. 2013;8,:e61550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raup DM. Sepkoski JJ. Periodic extinction of families and genera. Science. 1986;231,:833–836. doi: 10.1126/science.11542060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex MA. Etter RJ. Deep-Sea Biodiversity: Pattern and Scale. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rex MA, Etter RJ, Morris JS, Crouse J, McClain CR, Johnson NA, Stuart CT, Deming JW, Thies R. Avery R. Global bathymetric patterns of standing stock and body size in the deep-sea benthos. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2006;317,:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Risso A. Ichthyologie de Nice, ou histoire naturelle des poisons du Departement des Alpes Maritimes. Paris: Schoell; 1810. [Google Scholar]

- Risso A. Histoire naturelle des principales productions de l'Europe Méridionale et particulièrement de celles des environs de Nice et des Alpes Maritimes. Paris: Levrault; 1826. Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Roe HSJ. Midwater biomass profiles over the Madeira Abyssal Plain and the contribution of copepods. Hydrobiologia. 1988;167/168,:169–181. [Google Scholar]

- Santini F, Harmon LK, Carnevale G. Alfaro ME. Did genome duplication drive the origin of teleosts? A comparative study of diversification in ray-finned fishes. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9,:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopf TJM. Paleoceanography. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sepkoski JJ. A compendium of fossil marine animal genera. Bulletins of American Paleontology. 2002;363,:1–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan RE, Gradstein FM, Barnard LA, Bliefnick DM, Habib D, Jenden PD, Kagami H, Keenan EM, Kostecki J, Kvenvolden KA, Moullade M, Ogg J, Robertson AHF, Roth PH, Shipley TH, Wells L, Bowdler JL, Cotillon PH, Halley RB, Kinoshita H, Patton JW, Pisciotto KA, Premoli-Silva I, Testarmata MM, Tyson RV. Watkins DK. Early history of the Atlantic Ocean and gas hydrates on the Blake Outer Ridge: results of the deep sea drilling project leg 76. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 1982;93,:876–885. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KL, Jr, Ruhl HA, Bett BJ, Billett DSM, Lampitt RS. Kaufmann RS. Climate, carbon cycling, and deep-ocean ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106,:19211–19218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908322106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speers-Roesch B. Treberg JR. The unusual energy metabolism of elasmobranch fishes. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 2010;155,:417–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speers-Roesch B, Robinson JW. Ballantyne JS. Metabolic organization of the spotted ratfish, Hydrolagus colliei (Holocephali: Chimaeriformes): insight into the evolution of energy metabolism in the chondrichthyan fishes. Journal of Experimental Zoology A Comparative Experimental Biology. 2006;305,:631–644. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima R, Nishi H, Huber BT. Leckie M. Greenhouse world and the Mesozoic ocean. Oceanography. 2006;19,:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Thuy B, Gale AS, Kroh A, Kucera M, Numberger-Thuy LD, Reich M. Stöhr S. Ancient origin of the modern deep-sea fauna. PLoS One. 2012;7,:e46913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C-L, Rowe GT, Escobar-Briones E, Boetius A, Soltwedel T, Caley MJ, Soliman Y, Huettmann F, Qu F, Yu Z, Pitcher CR, Haedrich RL, Wicksten MK, Rex MA, Baguley JG, Sharma J, Danovaro R, MacDonald IR, Nunnally CC, Deming JW, Montagna P, Lévesque M, Weslawski JM, Wlodarska-Kowalczuk M, Ingole BS, Bett BJ, Billett DSM, Yool A, Bluhm BA, Iken K. Narayanaswamy BE. Global patterns and predictions of seafloor biomass using random forests. PLoS One. 2010;5,:e15323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White BN. Oceanic anoxic events and allopatric speciation in the deep sea. Biological Oceanography. 1987;5,:243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin RT, Arthur MA. Dean WE. History of water-column anoxia in the Black Sea indicated by pyrite framboid size distributions. Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1997;148,:17–525. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward AS. The antiquity of the deep-sea fish-fauna. Journal of Natural Science. 1898;12,:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey P. Siebenaller J. Trimethylamine oxide stabilizes teleost and mammalian lactate dehydrogenases against inactivation by hydrostatic pressure and trypsinolysis. Journal of Experimental Biology. 1999;202,:3597–3603. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.24.3597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz IO, Altiner D, Tekin UK, Tuysuz O, Ocakoglu F. Acikalin S. Cenomanian – Turonian Oceanic Anoxic Event (OAE2) in the Sakarya Zone, northwestern Turkey: sedimentological, cyclostratigraphic, and geochemical records. Cretaceous Research. 2010;31,:207–226. [Google Scholar]

Electronic Reference

- Froese R, editor; Pauly D, editor. 2013. FishBase. Available at www.fishbase.org (accessed February 2013)