Abstract

Purpose

Young adult survivors of childhood cancer (YASCC) are an ever-growing cohort of survivors due to increasing advances in technology. Today, there is a shift of focus to not just ensuring survivorship but also the quality of survivorship, which can be assessed with standardized instruments. The majority of standardized health related quality of life (HRQoL) instruments, however, are non-specific to this age group and the unique late effects within YASCC populations. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relevance and accuracy of standardized HRQoL instruments used with YASCC.

Methods

In a previous study, HRQoL items from several instruments (SF-36, QLACS, QLS-CS) were examined for relevance with a population of YASCC. Participants (n = 30) from this study were recruited for a follow-up qualitative interview to expand on their perceptions of missing content from existing instruments.

Results

Respondents reported missing, relevant content among all three of the HRQoL instruments. Results identified three content areas of missing information: (1) Perceived sense of self, (2) Relationships, and (3) Parenthood.

Conclusions

Existing HRQoL instruments do not take into account the progression and interdependence of emotional development impacted by a cancer diagnosis. The themes derived from our qualitative interviews may serve as a foundation for the generation of new items in future HRQoL instruments for YASCC populations. Further testing is required to examine the prevalence, frequency, and breadth of these items in a larger sample.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, Oncology, Young adult survivors, Missing content

Introduction

Survival rates for pediatric and adolescent cancer continue to increase each year [1], although it remains the leading disease-related cause of death for males and females aged 15 and 40. Incident rates for individuals in this age range are significantly higher than for pediatric cancers in populations younger than age 15 [2]. Young adult survivors of childhood cancer (YASCC) are increasingly becoming an area of focus in basic science research, healthcare delivery methods, and psychosocial interventions [3, 4]. This population in particular has vocalized concerns about the unique late effects, both physical and psychological, incurred from treatment or the cancer itself that can go unidentified in HRQoL instruments with non-specific constructs [5, 6]. Physical late effects can include having a compromised immune system, neurocognitive delays, or permanent disability. Psychological late effects can range from low self-esteem, difficulties in relationships, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the past, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) instruments were used to only identify these effects [7]; however, there has been a shift for using HRQoL instruments to not only identify but also monitor these effects over time to measure the quality of survivorship [8, 9].

The majority of standardized HRQoL instruments are non-specific to the age group and unique late effects within YASCC populations; however, in the absence of specific instruments, they and other generic instruments are frequently used. Such generic instruments include the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 (SF-36) [10], the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised [11], and Health Utility Index [12]. When used with YASCC populations, there is high variability between the outcomes of survivors versus healthy controls. Some cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have shown YASCC with better outcomes [13, 14], worse outcomes [15–17], or similar outcomes to control groups [18–20].

There are two notable HRQoL instruments specific to the survivor population: Quality of Life-Cancer Survivors (QOL-CS) [21] and the Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors (QLACS) [22]. Still, these were validated by and intended to be used for survivors of adult-onset cancer and not YASCC. The Impact of Survivorship-Cancer Scale (IOS-CS) is a recently developed HRQoL tool [23]. The development of the IOS-CS is an interpretation of responses from a semi-structured interview guide that shows a wide range of survivor needs, but does not highlight where the areas of existing HRQoL instruments are insufficient at capturing the unique needs of YASCC. One study utilized the Medical Outcome Study Scale (MOS-24), Worry Questionnaire, and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale to identify quality of life issues among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Results concluded that current HRQoL instruments may not be sufficient on their own, as none currently measure domains such as self-image or fertility, which were shown as a high concern to YASCC [24].

YASCC have unique, overlapping needs as they transition from child to adolescent, adolescent to young adult, and patient to survivor. No study has investigated the potential missing content from HRQoL instruments designed for YASCC. It is important to understand what factors are not captured in current instruments, which could potentially protect survivors from future negative physical and psychological outcomes by identifying areas in need of monitoring. The purpose of this study was to investigate the relevance and accuracy of standardized HRQoL domains used with YASCC through the conduct of qualitative interviews. It was hypothesized that these instruments would not have comprehensive domains capturing all relevant HRQoL indicators YASCC actually encounter.

Methods

This qualitative study was part of a parent study [25, 26] that focused on head-to-head comparisons of measurement properties between two survivor-specific HRQoL instruments (QLACS [22] and QLS-CS [21]) and a generic HRQoL instrument (SF-36 [27]). These instruments were chosen due to their wide use in clinical settings and reliability of the domain scores above the acceptable level (Cronbach’s α 0.72–0.91 for QLACS [22], 0.71–0.89 for QLS-CS [21], and 0.79–0.95 for SF-36 [28]). In the parent study, 151 YASCC were administered these three instruments over the phone and asked to identify any content areas perceived to be missing from the items. This study was approved by the University of South Florida’s and the University of Florida’s Institutional Review Board ensuring ethical compliance for studies involving human subjects. Participants who met the eligibility criteria were recruited: (1) between the ages of 21–30, (2) diagnosed with cancer prior to 18 years of age, and (3) off active treatment/therapy for at least 2 years. All cancer diagnoses were included, except skin cancers, carcinoma in situ, and precancerous conditions. From these criteria, 570 YASCC from the Cancer Data Center and the Cancer Survivorship Program at the University of Florida (UF) in Gainesville, FL, and 109 YASCC from the Cancer Registry of the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, FL, were identified. A primer letter was sent to all 679 YASCC; however, only 315 were actually eligible largely due to invalid contact information and in part due to true eligibility status regarding being off treatment.

From the eligible 315, a total of 151 YASCC participated in a phone interview for a response rate of 48%. Phone interviews were conducted using each instrument between February 2009 and October 2010: the QOL-CS, measuring HRQoL in long-term survivors, the QLACS, measuring daily functioning and well-being, the SF-36, measuring generic HRQoL domains, and the Crown Social Desirability Scale (CSDS), which measures socially desirable responding traits. At the completion of the phone interview, respondents were asked whether they would like to participate in a qualitative interview. We recruited 30 individuals to participate in an interview in which they expanded on the missing content areas identified during the phone interview and provided examples relevant to their lives discuss several HRQoL items more in-depth. The recruitment goal for the qualitative study was aimed at 50 participants from the larger cohort or until saturation was reached. After interim analysis at 30 participants, we determined no new information was emerging and thus saturation was reached. Six of these participants were in a centrally convenient location and thus participated in a focus group, while the remaining 24 participated in individual, face-to-face interviews.

Study instrument

The study team developed a 13-question semi-structured interview guide, which captured basic domains of the HRQoL instruments such as physical and social functioning. Demographic questions included age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, marital status, employment status, language, and self-reported current health status. The interview guide included questions on the meaning of quality of life and well-being, physical and mental functioning, pain, fatigue, body image, outlook for the future, etc. Participants provided consent for audio recording. The interview guide allowed participants to elaborate on closed-ended questions asked during the previous phone interview to determine relevance, accuracy, sensitivity, and missing content.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed by GQ, IH, DM, and KZ using inductive content analysis [29] and a combination of hand-coding and qualitative software. Content analysis is an established method that seeks to interpret the content of data through the process of coding, then classifying into distinct themes [30]. The transcripts were first analyzed using Atlas TI [31] to distinguish a priori codes from inductive codes based on the interview guide, cross-referenced to identify from which instrument(s) the inductive code was missing. Initial inductive codes were then organized by hand into categories of (1) missing from QLACS; (2) missing from QLS-CS; and (3) missing from SF-36. Each interview was assessed using the Crown Social Desirability Scale (CSDS). The results of the CSDS are not reported here because this measures social desirability bias and not HRQoL; however, these data were used to determine possible influences on HRQoL responses. Codes found to contain indicators of social desirability bias were reviewed by the research team to agree upon the appropriate inclusion. Codes that were missing in all instruments were separated and underwent several rounds of thematic validation [32]. Saturation was determined when no new codes emerged. Similar codes were grouped together, and predominant themes emerged to classify each group. All codes were agreed upon by the research team.

Results

The results presented here represent data from all 30 participants. The majority of those who participated in this study were Caucasian male (n = 20), employed (n = 25), have had some college (n = 20), and indicated that they were in good health (n = 25). There was an equal ratio of single to married participants (n = 15 single; n = 15 married).

Overall results of the qualitative analysis are shown in Table 1, with each code organized into one of three categories differentiated by instrument: (1) missing content in all instruments; (2) missing content in two instruments; and (3) missing content in one instrument.

Table 1.

Missing content by HRQoL instrument

| Missing in all instruments |

| Identity formation |

| Matured faster |

| Obligation to take care of their body |

| Obligation to be valuable |

| Survivor guilt |

| Desire for autonomy |

| Changed outlook on death (not afraid) |

| Missed opportunities/unfinished or unresolved issues |

| Make efforts to hide cancer/be ‘normal’ |

| Need for transitional/disability resources |

| Overprotective parents |

| Treated as if they still have cancer |

| Difficult to disclose/trust others’ willingness to keep friendship |

| Fear of burdening others |

| Worry about/have difficulties forming romantic relationships |

| Specific concerns related to scars |

| Worried children will get cancer |

| Fear/pain creates reluctance to have children |

| Concerned family will resent their poor health/limited functioning |

| Worried about fertility status |

| Missing in two instruments: QLACS/SF-36 |

| Lost faith in medicine due to late effects |

| Sufficiency of social support |

| Eating/sleeping fluctuations |

| Feelings of missing out (in present) |

| Religion helped cope |

| Desire for control |

| Missing in two instruments: QOL-CS/SF-36 |

| Worry about family genetics |

| Insurance |

| Feel like shouldn’t complain about physical and psychological difficulties in survivorship |

| Worry about death |

| Felt like couldn’t ask Drs. Questions |

| Have different perspective on “bad” QOL |

| Missing in one instrument: QLACS |

| Accommodating employers |

| Fear QOL will worsen |

| Missing in one instrument: SF-36 |

| Worry about recurrence |

| Feel a sense of purpose/appreciation after survival |

| Struggle with intimacy/sexuality |

| Financial worry/burden |

| Effects on concentration/memory |

The majority of participants also included feelings about future reproduction in their definitions of quality of life.

Missing content that fell into the category of “Missing in All Instruments” was classified into three themes utilizing the data analysis techniques described in the Methods section: (1) Perceived sense of self, (2) Relationships, and (3) Parenthood.

Perceived sense of self

YASCC expressed concerns that related to their sense of self. Development of survivors’ sense of self includes identity formation during their transition into young adulthood and striving for “normalcy” during their transition into survivorship. These comments are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Missing sense of self-domains and sub-domains in HRQoL instruments

| Sub-domain | Direct quote |

|---|---|

| Identity formation domain | |

| Matured faster | I did get a lot stronger… I remember walking around the hospital; nobody was there to babysit I was always very smart for my age but I ended up being a lot more mature and smart because of cancer. I’ve experienced things that other people don’t understand and I was 9 |

| Feelings of guilt (obligated to protect body; being a valuable member of family/society; survivor guilt) | I felt like I needed to spend more time and energy to get my outward person to match my inside person after everything they did for me I made a lot of friends who had cancer; most of them are dead now. I catch myself thinking why did I survive? Why didn’t they? That’s something that runs through my head quite a bit There isn’t anything, no obstacle that’s going to stop me from giving back and helping others. I would feel guilty if I didn’t |

| Desire for autonomy | I was and am very independent. I wanted to shun away from them always having to take care of me I’m sure they (school) would’ve provided me with a little cart but I never ask for that stuff. I wanted to do things on my own |

| Not afraid of death | For someone to be able to say, ‘ok, let’s just do what we can do; maybe we live, maybe we don’t.’ That’s a big step for a teen |

| Desire for normalcy domain | |

| Missed opportunities | My kids will show me words and my vision has been ruined from the cancer so I can’t see it. There’s a lot of things that I miss out on It upsets me that I can’t do the normal things I used to do like watching a movie |

| Make effort to be “Normal” | If somebody says, ‘oh he has cancer,’ I would say, ‘no, I don’t know what you’re talking about. No, not me I looked so foreign when I looked in the mirror. My hair was curly and brown when it used to be blonde and straight. I straightened and bleached it just so I could feel normal again The doctors were my family. They were one of the biggest parts of my life and death so it’s really weird that after I’m cured they forget about you but I still needed things to feel normal |

Relationships

The highest frequency of missing content was regarding relationships and parenthood. The majority of YASCC discussed the impact of their previous cancer experience and how this influences their behavior and emotional regulations within current relationships. These comments are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Missing relationship domains and sub-domains from HRQoL instruments

| Impact on relationships | |

|---|---|

| Sub-domain | Direct quote |

| External barriers (overprotective parents; treated as if still has cancer) | My mom wants to talk every 2 days. If I don’t she thinks I’m sick. She’s always worrying and doesn’t want me to do anything. I think parents should go through a psychological eval before you’re released from the hospital People are always surprised that I’m doing well and that I have a full head of hair. People think it should be a bigger deal to me but I always have to explain that it was so long ago and I don’t have it anymore |

| Internal barriers (difficulty trusting others; fear of burdening others; difficulties forming romantic relationships; concerns over scarring) | I don’t like the whole idea of making accommodations for me. I don’t want to burden people with making accommodations for me I’m not very social. When I had cancer there were always people that come in and out so you never get too attached I had some people I was dating react negatively to the scars and some who just play the sympathy card. I am worried that they won’t understand me and just pity me I usually end up lying about it (scar) saying I got in a car accident. I know I’m self- conscious about it but I will definitely judge what guys I date based on their reaction to it |

Parenthood

The majority of comments not captured in HRQoL instruments pertained to feelings of loss regarding their expectations of traditional parenthood due to physical and psychological limitations. These comments are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Missing parenthood domains and sub-domains from HRQoL instruments

| Sub-domain | Direct quote |

|---|---|

| Impact on relationships domain | |

| Loss of traditional parenthood | |

| Concern over transmission to offspring | I worry about them (kids) getting cancer because of me but I just pray. I pray a lot Oh yes of course I’m worried about my future kids getting cancer. My mind goes to do I really wanna have kids; do I wanna put them through this… |

| Concern family will resent limited physical functioning | I just have this guilt that I shouldn’t carry I know but I would fear that my kids and husband would get tired of me always having health issues Whenever I have a bad migraine I think, what are you going to do if you have a kid? They won’t get the attention they need and end up hating me |

| Concern over fertility status | I’m 27 and still don’t have a kid. It’s embarrassing to me somewhat. As soon as I got out of the hospital I had questions but they said you’re fine, I still wonder though I’m afraid to say I do want to have babies because I’m going to become obsessed with it, but because it’s not something I can control it’ll tear my marriage apart if I can’t |

Discussion

Many studies have been conducted to compare HRQoL between YASCC and the general population, typically using generic instruments such as the SF-36. Studies examining HRQoL within cancer populations have often used the QLACS and QLS-CS. These instruments were designed for adult cancer populations; however, they lack precision and relevance for the YASCC population. Although some studies reported better [33, 34] or impaired [17, 35] HRQoL outcomes for YASCC compared to the general population, a majority of the studies that reported HRQoL was actually equivalent [18–20] between YASCC and general populations. However, this does not truly mean that HRQoL of YASCC is not impaired. Instead, it may imply that the existing generic instruments are not comprehensive or precise enough to measure specific HRQoL for YASCC. The generic instruments only capture the impact of cancer or treatment on the basic daily functioning rather than issues specific to YASCC such as developmental milestones. The use of qualitative studies may provide better answers to identify specific themes of HRQoL for YASCC.

Our thematic findings are both consistent and inconsistent with previous qualitative studies. For example, Jones and colleagues reported that childhood survivors might experience an identity paradox when making the transition to survivor, which can contribute to their sense of isolation and risk of health-detracting behaviors [36]. Brown and colleagues found that family and parental supports are useful in outlook of their future, especially career development, and YASCC tent to help other people [37]. However, our findings suggest that several YASCC complain about over protection from their parents. Similarly, Cantrell and Conte’s qualitative study supports the findings of some sub-domains, such as feelings of survivor guilt, and finding a sense of self. However, survivors in their study also looked for acknowledgement from peers that they were still “sick,” (p. 318) whereas YASCC in our study desired an identity that reaffirmed they were no longer “sick” and that they were “a survivor” [38].

From a developmental perspective, experiencing cancer during childhood and adolescence can have significant impacts on psychological and behavioral processes as adults. The experience has intertwined itself with survivors’ sense of self, which impacts self-esteem, self-efficacy, self-awareness, and overall identity formation. Cancer can disrupt the development of a sense of self by unexpectedly confronting the child or teen with physical changes, disruptions in socialization, the increased need to rely on parents, and the idea of death [39]. Damon and Hart present a stage-type model of how a child actualizes their sense of self: (1) initial awareness of self based on competencies while engaging in a variety of activities; (2) awareness of physical characteristics such as gender; (3) shifting into defining themselves by internal qualities; and (4) age-related integration of self into the world around them [40]. Because each stage builds on the next, cancer interferes not only physically but also psychologically with the survivor’s view of the world and the role they assume, and how they interpret their own quality of life, a process unique to YASCCs. A sense of self includes identify formation, which progresses as children and adolescents transition into various stages of development taking with them expectations, competencies, and roles within the world. Various identities may result from the integration of a cancer experience. One study found that adolescent cancer survivors had a foreclosed identity status, meaning they have committed to a value system or prematurely decided what identity they would have instead of exploring what value system fit them best. However, this was found to be an adaptive coping mechanism especially in cases where survivors exhibited symptoms of PTSD and indicated conflict within the family [41].

How a child or teen negotiates their diagnosis with the development of their sense of self influences future quality of life outcomes [42]. Findings presented from our study are consistent with the literature regarding childhood cancer survivors. Desire for normalcy, feelings of early psychological maturation, and difficulties in developing relationships have been well documented [43–47]. Despite this, HRQoL tools used for cancer survivors have domains that are unique to those with adult-onset cancer and lack specific content-related questions for YASC.

The high concerns among survivors about future parenthood highlight this specific unaddressed need. The majority of survivors did not know their fertility status, which has been documented within this population [48]. Incident rates of parenthood have been shown to be lower in childhood cancer survivors compared to the national average [49]. This could be due to physical infertility, or psychological concerns related to conceiving or carrying a pregnancy, and parenting. Difficulties with conception have been linked to the intensity of the treatment in males [50] and females who conceive post-diagnosis are often considered high-risk pregnancies [51]. Survivors have indicated that their cancer experience increases the value they place on family, enhancing their drive to create families of their own. Fear of transmission or birth defects from treatment have been shown as a deterrence from creating their own families [52], which is also shown in the YASCC interviewed for this study.

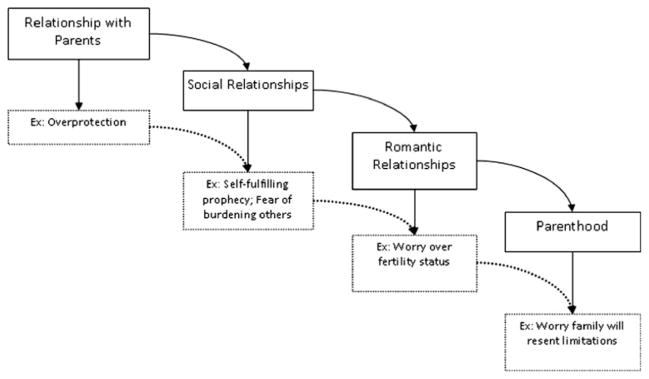

Existing HRQoL instruments do not take into account the progression and interdependence of development impacted by a cancer diagnosis. Realistically, the fragmented and separate domains of existing HRQoL instruments cascade upon one another, which affect the survivor as a whole person. Concerning relationships, early negotiations of dependence versus separation with parents often impact the progressive components of development and eventually parenthood; however, these negotiations are very specific to YASCC (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Impact of a cancer diagnosis on relationships

There are limitations to this study. Results may be biased due to the demographics of participants who were from Florida, largely Caucasian males, employed, had some college, and self-reported good health. Further, three popular HRQoL instruments were tested; however, it is unknown whether additional missing content would have been identified if other HRQoL instruments were used. An inherent limitation in qualitative research is the inability to generalize the results to other populations; however, these data show trends that should be examined in a nationally representative sample.

Conclusion

The codes derived from our qualitative interview can serve as a foundation for comprehensive item generation. These results identify specific issues identified by YASCC that are not presently captured by the current instruments. In this regard, the information is useful for refining the existing HRQoL instruments by either adding new items into the existing domains or standalone instruments. Future pilot testing is required to examine the prevalence, frequency, and breadth of these items in a larger sample. During pilot testing, additional items in HRQoL tools for YASCC should be examined to determine whether subjects interpret the relevance of those items similar to those in this study. It can also be expected that future HRQoL instruments will need continual testing to ensure that they are accurately assessing the needs of YASCC in an ever changing society.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by NIH/NICHD K23 HD057146-03 and Moffitt/UF/Shands HealthCare Consortium Joint Cancer Center Pilot Fund UF80052.

Abbreviations

- YASCC

Young adult survivors of childhood cancer

- HRQoL

Health-related quality of life

- PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- SF-36

Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36

- QOL-CS

Quality of Life—Cancer Survivors

- QLACS

Quality of Life in Adult Cancer Survivors

- MOS-24

Medical Outcome Study Scale

- MCSCS

Crown Social Desirability Scale

- UF

University of Florida

Contributor Information

Gwendolyn P. Quinn, Email: gwen.quinn@moffitt.org, Health Outcomes and Behavior, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, 12902 Magnolia Drive, MRC CANCONT, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL, USA

I-Chan Huang, Health Outcomes and Policy, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Devin Murphy, Jonathan Jaques Children’s Cancer Center, Miller Children’s Hospital, Long Beach, CA, USA.

Katie Zidonik-Eddelton, Health Outcomes and Policy, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Kevin R. Krull, Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Control, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER cancer statistics review: 1975–2005. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleyer A, Barr R. In: Cancer epidemiology in older adolescents and young adults 15 to 29 years of age, including seer incidence and survival, highlights and challenges. Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, et al., editors. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006. pp. 1975–2000. NIH publication 06-5767. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evan EE, Zeltzer LK. Psychosocial dimensions of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Cancer. 2006;107:1663–1671. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; NIH publication 06-6067. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaauwbroek R, Groenier KH, Kamps WA, Meyboom-de Jong B, et al. Late effects in adult survivors of childhood cancer: The need for life-long follow-up. Annals of Oncology. 2007;18(11):1898–1902. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, Termuhlen AM, et al. Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2009;18(10):2626–2635. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JCI, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(2):435–446. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaauwbroek R, Stant AD, Groenier KH, Kamps WA, et al. Health-related quality of life and adverse late effects in adult (very) long-term childhood cancer survivors. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boman KK. Assessing psychological and health-related quality of life (HRQL) late effects after childhood cancer. Acta Paediatrica. 2007;96:1265–1268. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taïeb O, Moro M, Baubet T, Revah-Lévy A, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms after childhood cancer. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;12(6):255–264. doi: 10.1007/s00787-003-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlong WJ, Feeny D, Torrance GW, Barr RD. The health utilities index (HUI) system for assessing health-related quality of life in clinical studies. Annals of Medicine. 2001;33:375–384. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Siimes MA, Hovi L, Holmberg C, Boyd H, et al. Health-related quality of life of adults surviving malignancies in childhood. European Journal of Cancer. 1996;32A:1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elkin TD, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, Fairclough D. Psychological functioning of adolescent and young adult survivors of pediatric malignancy. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1997;29:582–588. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199712)29:6<582::aid-mpo13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novakovic B, Fears TR, Horowitz ME, Tucker MA, Wexler LH. Late effects of therapy in survivors of Ewing’s sarcoma family tumors. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/oncology. 1997;19:220–225. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Caron HN, Last BF. Quality of life and current coping in young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Positive expectations about the further course of the disease were correlated with better quality of life. Psychooncology. 2006;15:31–43. doi: 10.1002/pon.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeltzer LK, Chen E, Weiss R, Guo MD, Robison LL, Meadows AT, et al. Comparison of psychologic outcome in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia versus sibling controls: A cooperative children’s cancer group and national institutes of health study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:547–556. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felder-Puig R, Formann AK, Mildner A, Bretschneider W, Bucher B, Windhager R, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment of young patients after treatment of bone cancer. Cancer. 1998;83:69–75. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980701)83:1<69::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, Shaw AK, Speechley KN. Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:2527–2535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moe PJ, Holen A, Glomstein A, Madsen B, et al. Long-term survival and quality of life in patients treated with a national all protocol 15–20 years earlier: IDM/HDM and late effects? Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 1997;14:513–524. doi: 10.3109/08880019709030908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Grant M. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Quality of Life Research. 1995;4:523–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00634747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Avis NE, Smith KW, McGraw S, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Carver CS. Assessing quality of life in adult cancer survivors (QLACS) Quality of Life Research. 2005;14:1007–1023. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, Petersen L, et al. Assessing the impact of cancer: Development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(5):407–421. doi: 10.1002/pon.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voûte PA, de Haan RJ, et al. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(12):867–881. doi: 10.1002/pon.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang I, Quinn GP, Eddleton KZ, Murphy DC, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of quality of life instruments for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1315-5. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang I, Quinn GP, Wen P, Shenkman EA, et al. Developing item banks of health-related quality of life measurement for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Quality of Life Research. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0055-9. (in press) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reulen RC, Zeegers MP, Jenkinson C, Lancashire ER, et al. The use of the SF-36 questionnaire in adult survivors of childhood cancer: Evaluation of data quality, score reliability, and scaling assumptions. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4(77) doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paton MQ. Qualitative evaluation methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhr T. User’s manual for ATLAS.ti 5.0. Berlin: ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton MQ. Qualitative research. Encyclopedia of statistics in behavioral science. London: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Apajasalo M, Sintonen H, Siimes MA, Hovi L, et al. Health-related quality of life of adults surviving malignancies in childhood. European Journal of Cancer. 1996;32A(8):1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elkin TD, Phipps S, Mulhern RK, Fairclough D. Psychological functioning of adolescent and young adult survivors of pediatric malignancy. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1997;29(6):582–588. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199712)29:6<582::aid-mpo13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stam H, Grootenhuis MA, Caron HN, Last BF. Quality of life and current coping in young adult survivors of childhood cancer: Positive expectations about the further course of the disease were correlated with better quality of life. Psychooncology. 2006;15(1):31–43. doi: 10.1002/pon.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones BL, Parker-Raley J, Barczyk A. Adolescent cancer survivors: Identity paradox and the need to belong. Qualitative Health Research. 2011;21(8):1033–1040. doi: 10.1177/1049732311404029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown C, Pikler VI, Lavish LA, Keune KM, et al. Surviving childhood leukemia: Career, family, and future expectations. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(1):19–30. doi: 10.1177/1049732307309221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cantrell MA, Conte TM. Between being cured and being healed: the paradox of childhood cancer survivorship. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(3):312–322. doi: 10.1177/1049732308330467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zebrack BJ. Psychological, social, and behavioral issues for young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(S10):2289–2294. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Damon W, Hart D. The development of self-understanding from infancy through adolescence. Child Development. 1982;53(4):841–864. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madan-Swain A, Brown RT, Foster MA, Vega R, et al. Identity in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25(2):105–115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woodgate R, McClement S. Sense of self in children with cancer and in childhood cancer survivors: A critical review. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1997;14(3):137–155. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4542(97)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinds PS, Martin J. Hopefulness and the self-sustaining process in adolescents with cancer. Nursing Research. 1988;37(6):336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hockenberry-Eaton M, Minick P. Living with cancer: Children with extraordinary courage. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1994;21(6):1025–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Orr DP, Hoffmans MA, Bennetts G. Adolescents with cancer report their psychosocial needs. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1984;2(2):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weekes DP, Kagan S. Adolescents completing cancer therapy: Meaning, perception, and coping. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1994;21(4):663–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rechner M. Adolescents with cancer: Getting on with life. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1990;7(4):139–144. doi: 10.1177/104345429000700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zebrack BJ, Casillas J, Nohr L, Adams H, et al. Fertility issues for young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(10):689–699. doi: 10.1002/pon.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madanat LMS, Malila N, Dyba T, Hakulinen T, et al. Probability of parenthood after early onset cancer: A population-based study. International Journal of Cancer. 2008;123(12):2891–2898. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brydøy M, Fosså SD, Klepp O, Bremnes RM, et al. Paternity following treatment for testicular cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(21):1580–1588. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Magelssen H, Melve KK, Skjaerven R, Fosså SD. Parenthood probability and pregnancy outcome in patients with a cancer diagnosis during adolescence and young adulthood. Human Reproduction. 2008;23(1):178–186. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schover LR. Motivation for parenthood after cancer: A review. JNCI Monographs. 2005;2005(34):2–5. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]