Abstract

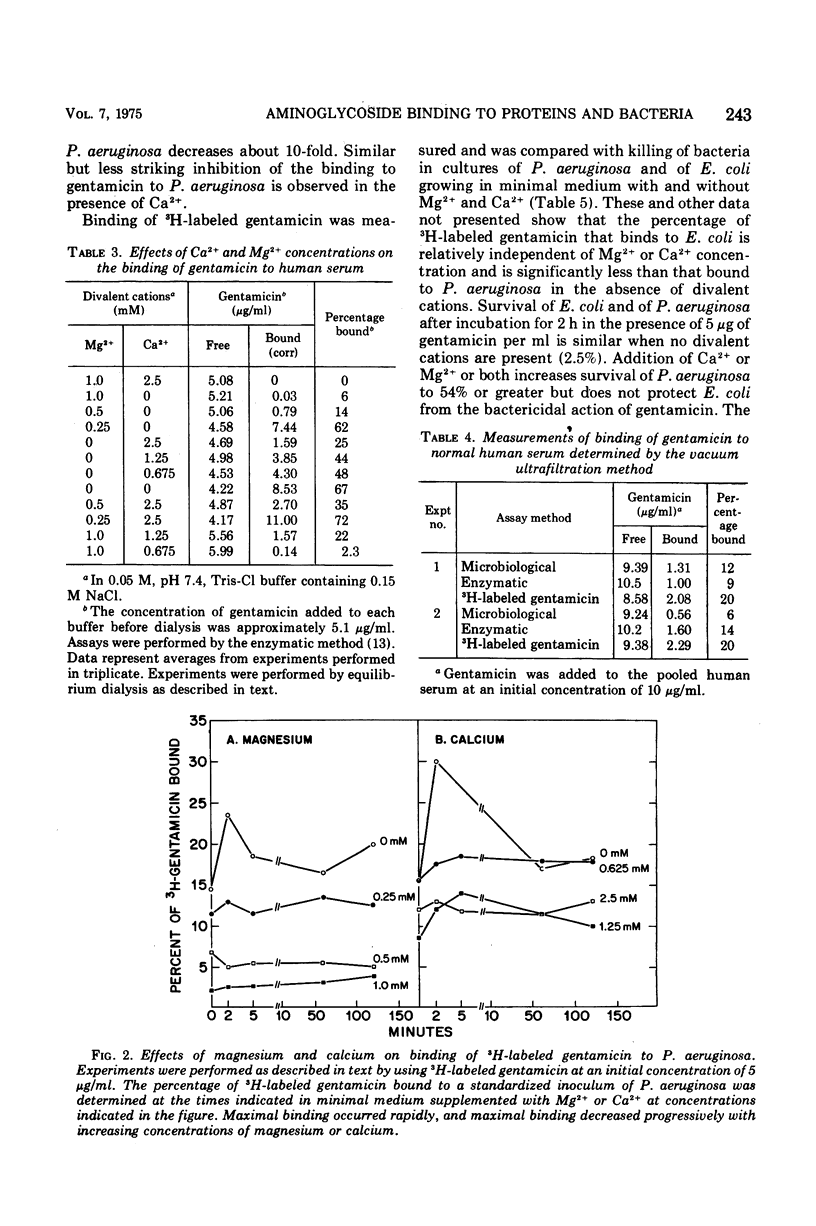

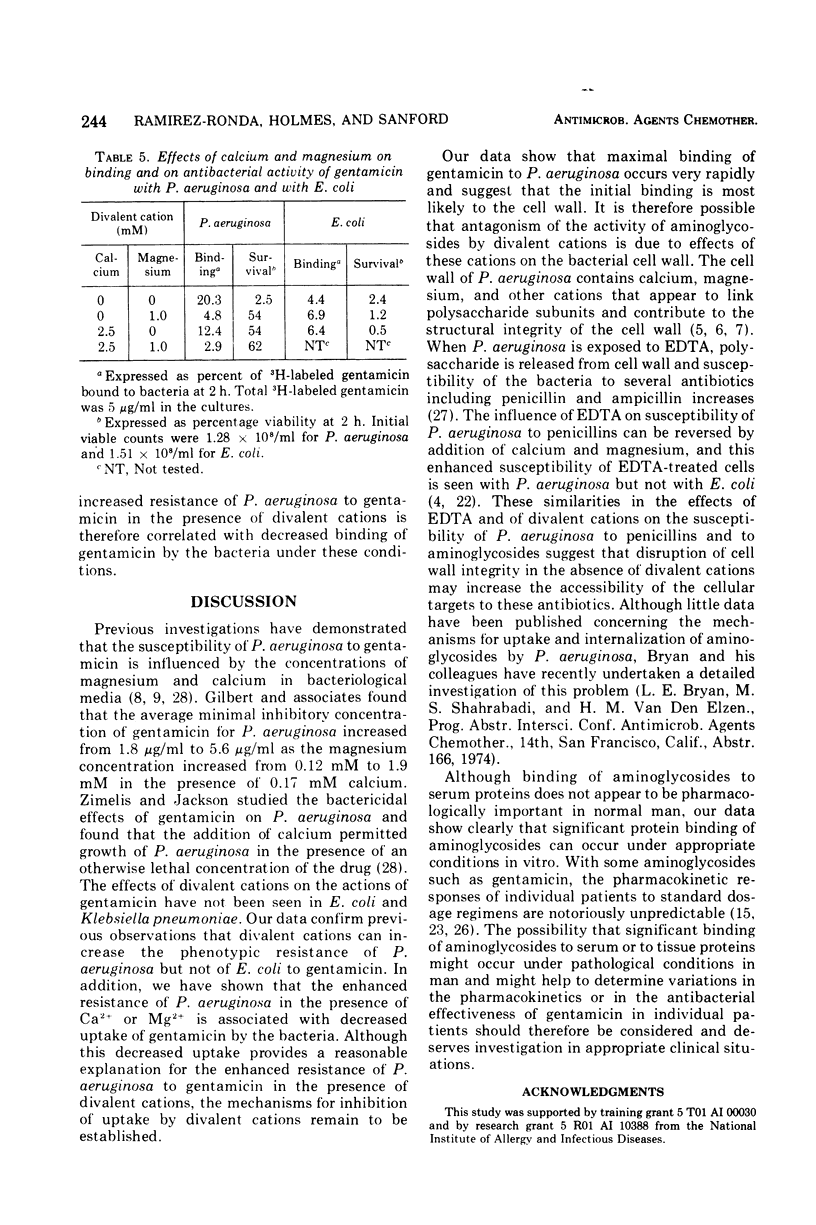

Binding of gentamicin and related deoxystreptamine-containing aminoglycoside antibiotics to proteins in human serum can vary significantly with changes in experimental conditions. The concentrations of divalent cations are important variables, and binding increases progressively as the concentrations of calcium and magnesium decrease. Maximal binding of deoxystreptamine-containing aminoglycosides to human serum is approximately 70% in the absence of divalent cations. The binding of 3H-labeled gentamicin to Pseudomonas aeruginosa increases and its bactericidal activity against P. aeruginosa is enhanced in the absence of divalent cations. In contrast, binding of 3H-labeled gentamicin to Escherichia coli and bactericidal activity against E. coli do not vary significantly in the presence and in the absence of divalent cations. Interference with uptake of gentamicin provides a plausible explanation for the observation that the minimal inhibitory concentration of gentamicin for P. aeruginosa increases as the concentration of calcium or magnesium in bacteriological media increases. Although significant binding of deoxystreptamine-containing aminoglycosides to plasma proteins does not occur under normal physiological conditions in man, the possibility remains that variations in protein binding of these aminoglycosides might be significant under pathological conditions.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BROWN A. D. ASPECTS OF BACTERIAL RESPONSE TO THE IONIC ENVIRONMENT. Bacteriol Rev. 1964 Sep;28:296–329. doi: 10.1128/br.28.3.296-329.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. V., Brodie J. L., Benner E. J., Kirby W. M. Simplified, accurate method for antibiotic assay of clinical specimens. Appl Microbiol. 1966 Mar;14(2):170–177. doi: 10.1128/am.14.2.170-177.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J. V., Kirby W. M. A rapid, modified ultrafiltration method for determining serum protein binding and its application to new penicillins. J Lab Clin Med. 1965 Nov;66(5):721–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS F. M. COMPOSITION OF CELL WALLS OF AGEING PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA AND SALMONELLA BETHESDA. J Gen Microbiol. 1964 Mar;34:379–388. doi: 10.1099/00221287-34-3-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagon R. G. Cell wall-associated inorganic substances from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1969 Feb;15(2):235–236. doi: 10.1139/m69-039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagon R. G., Simmons G. P., Carson K. J. Evidence for the presence of ash and fivalent metals in the cell wall of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1965 Dec;11(6):1041–1042. doi: 10.1139/m65-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrod L. P., Waterworth P. M. Effect of medium composition on the apparent sensitivity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to gentamicin. J Clin Pathol. 1969 Sep;22(5):534–538. doi: 10.1136/jcp.22.5.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. N., Kutscher E., Ireland P., Barnett J. A., Sanford J. P. Effect of the concentrations of magnesium and calcium on the in-vitro susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to gentamicin. J Infect Dis. 1971 Dec;124 (Suppl):S37–S45. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R. C., Regamey C., Kirby W. M. Serum protein binding of the aminoglycoside antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972 Sep;2(3):214–216. doi: 10.1128/aac.2.3.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyselynck A. M., Forrey A., Cutler R. Pharmacokinetics of gentamicin: distribution and plasma and renal clearance. J Infect Dis. 1971 Dec;124 (Suppl):S70–S76. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUMMEL J. P., DREYER W. J. Measurement of protein-binding phenomena by gel filtration. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1962 Oct 8;63:530–532. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M. J., Davies J. Enzymatic acetylation as a means of determining serum aminoglycoside concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973 Oct;4(4):497–499. doi: 10.1128/aac.4.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes R. K., Sanford J. P. Enzymatic assay for gentamicin and related aminoglycoside antibiotics. J Infect Dis. 1974 May;129(5):519–527. doi: 10.1093/infdis/129.5.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUNIN C. M. INHIBITORS OF PENICILLIN BINDING TO SERUM PROTEINS. J Lab Clin Med. 1965 Mar;65:416–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye D., Levison M. E., Labovitz E. D. The unpredictability of serum concentrations of gentamicin: pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in patients with normal and abnormal renal function. J Infect Dis. 1974 Aug;130(2):150–154. doi: 10.1093/infdis/130.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunin C. M., Craig W. A., Kornguth M., Monson R. Influence of binding on the pharmacologic activity of antibiotics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1973 Nov 26;226:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb20483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon W. A., Ezer J., Wilson T. W. Radioimmunoassay for measurement of gentamicin in blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973 May;3(5):585–589. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshew B. H., Holmes R. K., Baxter C. R. Comparison of a radioimmunoassay with an enzymatic assay for gentamicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975 Jan;7(1):107–109. doi: 10.1128/aac.7.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REPASKE R. Lysis of gram-negative organisms and the role of versene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958 Nov;30(2):225–232. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riff L. J., Jackson G. G. Pharmacology of gentamicin in man. J Infect Dis. 1971 Dec;124 (Suppl):S98–105. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone W. J., Bryant R. E., Hoyumpa A., Schenker S. Renal neomycin excretion in the dog. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1974 Mar;145(3):1074–1080. doi: 10.3181/00379727-145-37956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser R., Asscher A. W., Wimpenny J. In vitro reversal of antibiotic resistance by ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid. Nature. 1968 Sep 28;219(5161):1365–1366. doi: 10.1038/2191365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters R. E., Litwack K. D., Hewitt W. L. Relation between dose and levels of gentamicin in blood. J Infect Dis. 1971 Dec;124 (Suppl):S90–S95. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimelis V. M., Jackson G. G. Activity of aminoglycoside antibiotics aganst Pseudomonas aeruginosa: specificity and site of calcium and magnesium antagonism. J Infect Dis. 1973 Jun;127(6):663–669. doi: 10.1093/infdis/127.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]