Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to examine the relationship between prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) and pubertal development. Children (n=192; 41% with PCE) completed the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen, et al. 1988) and provided salivary dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) samples at 6 month intervals from 11 to 13 years. PCE was examined as a predictor of pubertal status, pubertal tempo, and DHEA levels in mixed models analyses controlling for age, sex, environmental risk, neonatal medical problems, other prenatal exposures, and BMI. PCE interacted with age such that PCE predicted slower pubertal tempo during early adolescence. PCE also interacted with age to predict slower increases in DHEA levels during early adolescence. These findings suggest that PCE may affect pubertal development and, if slower pubertal tempo continues, could lead to delayed pubertal status in mid-adolescence.

Keywords: prenatal cocaine exposure, pubertal status, pubertal tempo, dehydroepiandrosterone

1. Introduction

Prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) has been associated with a variety of adverse developmental outcomes including attention and inhibitory control deficits, risky behavior, aggression, and cognitive deficits (Ackerman, et al. 2010; Bendersky, et al. 2006; Bennett, et al. 2007; Bennett, et al. 2008; Bennett, et al. 2013; Lambert and Bauer 2012). Research, however, has yet to examine the possible relationship between PCE and pubertal development despite findings that PCE is associated with a variety of other biophysiological effects. These include decreased cerebral blood flow (Rao, et al. 2007), differences in frontal lobe white matter and gray matter (Grewen, et al. 2014; Warner, et al. 2006), and a blunted cortisol response to stress (Lester, et al. 2010). Specific to physical development, PCE has been associated with decreased intrauterine growth and with lower weight or slower growth during middle childhood (Bandstra, et al. 2001; Bateman and Chiriboga 2000; Bendersky and Lewis 1999; Eyler, et al. 1998; Lutiger, et al. 1991; Minnes, et al. 2006; Richardson, et al. 2007; Richardson, et al. 1999; Richardson, et al. 2013), although one study found PCE to be associated with greater body mass index (BMI) at 9 years (Shankaran, et al. 2010). Collectively, these findings suggest that PCE can affect physical development.

Pubertal development, including the timing of pubertal milestones, has been shown to be affected by teratogen exposure (Shrestha, et al. 2011; Wohlfahrt-Veje, et al. 2012a; Wohlfahrt-Veje, et al. 2012b). Among studies of prenatal substance exposure, tobacco has been most frequently examined. Boys, but not girls, prenatally exposed to tobacco reported reaching pubertal milestones earlier than their unexposed peers (Fried, et al. 2001). Similarly, a retrospective study of Danish men also found prenatal tobacco exposure to be associated with earlier pubertal onset (Ravnborg, et al. 2011). While prenatal exposures are generally more apt to affect males (Kestler, et al. 2012; Moe and Slinning 2001), girls whose mothers smoked heavily during pregnancy have been found to reach menarche at a younger age than unexposed girls in most studies (D'Aloisio, et al. 2013; Ernst, et al. 2012; Maisonet, et al. 2010; Morris, et al. 2010; Rubin, et al. 2009; Shrestha, et al. 2011; Windham, et al. 2004), although two studies found the opposite effect (Ferris, et al. 2010; Windham, et al. 2008). While the effects of tobacco exposure may be distinct from the effects of cocaine exposure, these studies indicate that prenatal substance exposure can affect the timing of pubertal development.

Research on pubertal development has traditionally focused on pubertal differences at specific age points (i.e., pubertal status). Studies of pubertal development, however, should examine both pubertal status and pubertal tempo. Pubertal status is defined as a child's pubertal development relative to same-sex and same–age peers at a given time point. In contrast, pubertal tempo is defined as the rate of change in pubertal development over a given period of time. Pubertal tempo is important because it has unique psychosocial correlates. For example, pubertal tempo was found to predict depressive symptoms better than pubertal status for boys since boys who developed more rapidly did not experience the reduction in depressive symptoms that their slower developing peers experienced (Mendle, et al. 2010). Similarly, rapid pubertal change has predicted increased depressive symptoms, internalizing problems, and externalizing problems (Ge, et al. 2003; Kretschmer, et al. 2013; Marceau, et al. 2011). These findings are consistent with the maturation compression hypothesis, which proposes that rapid pubertal tempo requires a relatively quick adaptation to new biological and social milestones, potentially increasing risk for adjustment problems (Mendle 2014). The precise mechanisms by which individual differences in pubertal tempo emerge is unclear, but may involve hormonal as well as psychosocial factors (Mendle 2014). While both pubertal status and pubertal tempo may contribute to adjustment, they are not consistently correlated with each other (Marceau, et al. 2011). As such, both pubertal status and tempo should be examined in relationship to PCE.

In addition to self-reports of pubertal status and tempo, hormonal changes can be used as a marker of pubertal development. Noticeable physical changes associated with puberty are preceded by hormonal changes such as increases in dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), an adrenal androgen and a precursor to testosterone and estrogen. DHEA levels rise dramatically during fetal development, when it may play a role in neuronal development (Compagnone and Mellon 1998), and then decline after the first year of life (Havelock, Auchus, & Rainey, 2004). At age 6 to 7 years, DHEA production again increases, corresponding to the beginning of adrenarche (Havelock, et al. 2004; Sulcova, et al. 1997), which is also characterized by axillary and pubic hair growth and the acceleration of bone growth and maturation (Papadimas 1997). DHEA is moderately correlated with pubertal status for both boys and girls (Shirtcliff, et al. 2007).

Apart from the possible teratogenic effects of prenatal substance exposure, psychosocial factors can also play a role in pubertal development. For example, the absence of a biological father or presence of a stepfather-figure in the home has been found to predict earlier pubertal development among girls (Ellis 2004; Ellis and Garber 2000; Tither and Ellis 2008). Likewise, maternal depression and family stress predict earlier pubertal development, especially for girls (Belsky, et al. 2007; Ellis and Garber 2000; Hulanicka 1999; Hulanicka, et al. 2001; Kim and Smith 1998; Saxbe and Repetti 2009).

The current study sought to examine individual differences in pubertal development as a function of PCE in a longitudinal study of children who were seen every 6 months between 11 and 13 years. We chose to focus on this age range because it captures the time of greatest variability in pubertal development for children in the United States (Parent, et al. 2003). In examining PCE as a predictor of pubertal development, we controlled for the effects of prenatal tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana exposure as well as neonatal medical problems, which also have been associated with differences in pubertal timing (Proos, et al. 2011). Given that increased BMI may be related to PCE (Shankaran, et al. 2010) and has been associated with earlier pubertal development (He and Karlberg 2001; Kaplowitz 2008), we also controlled for BMI. Likewise, given that pubertal development may be affected by psychosocial risk factors such as father absence, step-father presence, maternal depression, and family stress, these factors were examined in the current study, along with general environmental risk.

This study is the first to examine pubertal status and tempo in children with PCE. The study had three major aims. First, we examined whether children with PCE exhibit differences in pubertal development compared to their unexposed peers. In doing so, we examined differences in both pubertal status and pubertal tempo across ages 11 to 13. Second, we examined whether children with PCE exhibit differences in DHEA compared to their unexposed peers, both in mean levels and rate of change across ages 11 to 13. Third, we examined whether sex moderated any observed effects, based on prior research finding greater PCE effects for boys than girls (e.g., (Bennett, et al. 2008; Carmody, et al. 2011; Kestler, et al. 2012).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 192 children (52% male; 41% with PCE [46% of who were male]) and their mothers from a longitudinal study on the developmental effects of prenatal substance exposure. Pregnant women attending prenatal clinics in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Trenton, New Jersey were enrolled between February 1993 and December 1995. Children who were born before 32 weeks of gestation, required special care or oxygen therapy for more than 24 hours, exhibited congenital anomalies, or who were exposed to opiates or PCP in utero were excluded. Of the 258 children who participated in the first laboratory visit at 4 months, 192 children provided at least one assessment of pubertal status between the ages of 11.0 and 13.5. No significant differences were observed in perinatal variables (cocaine, alcohol, cigarette, or marijuana exposure; neonatal health problems), maternal age, or environmental risk at birth between participants in the current sample and those who did not participate. Mean child age at the six visits was as follows: 11.09 (SD=0.14), 11.61 (0.16), 12.08 (0.16), 12.58 (0.24), 13.09 (0.16), and 13.68 (0.22). Mothers were predominantly African-American (90%) and ranged in age from 13.7 to 42.1 (M = 25.9; SD = 6.0) years at the time of their child's birth. Three percent of caregivers reported using cocaine, marijuana, opiates, heroine, PCP, or “other street drugs” in the 6 months prior to study visits during the current time period.

2.2. Procedure

At 11.0, 11.5, 12.0, 12.5, 13.0, and 13.5 years, children's pubertal status and salivary DHEA levels were assessed. Examiners were blind to the children's drug exposure status. Incentives were provided to participants in the form of vouchers for use at local stores at each visit.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Predictors of Pubertal Development

2.3.1.1. Prenatal substance exposure

Prenatal substance exposure was assessed using a semi-structured interview administered to the mother within 2 weeks of their child's birth. The interview included questions assessing the frequency and amount of the mother's use of cocaine, alcohol, cigarettes, marijuana, and other substances throughout pregnancy. PCE was confirmed by analysis of the newborn's meconium for the presence of benzoylecgonine (cocaine metabolite) using radioimmunoassay followed by confirmatory gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. PCE was dichotomized (i.e., into unexposed and exposed groups; 0 vs. 1) in all analyses as prior reports from this sample have found the dichotomous measure to best predict outcomes.

2.3.1.2. Neonatal medical problems

Neonatal medical problems were abstracted by nurses from hospital records at birth using the Hobel Scale, a neonatal medical risk scale based on 35 possible complications (Hobel, et al. 1973). Complications included general factors (e.g., low birth weight, fetal anomalies, and feeding problems), respiratory problems (e.g., congenital pneumonia, apnea, and meconium aspiration syndrome), metabolic disorders (e.g., failure to gain weight and hypoglycemia), cardiac problems (e.g., murmur and cardiac anomalies), and CNS problems (e.g., CNS depression and seizures). Items were summed such that higher scores indicated greater neonatal medical problems, and log transformed to correct for skew.

2.3.1.3. Environmental risk

A composite environmental risk score was computed from variables obtained by maternal interview at the 10 year laboratory visit. The score included maternal life stress based on the Social Environment Inventory (Orr, et al. 1992), maternal social support network size based on the Norbeck Social Support Questionnaire (Norbeck, et al. 1981), the number of regular caregivers (greater number being associated with higher risk), the irregularity of the child's schedule and the instability of the child's surroundings from the Family Chaos Scale (R. Seifer, personal communication, 1993), single parenthood (single parent = higher risk), maternal education (reverse scored), and public assistance status (whether the family received Temporary Assistance to Needy Families [TANF] funding). Each variable was standardized and summed. This cumulative risk score was then rescaled as a T-score (M = 50, range = 25 to 87). Such aggregate scores are more stable than individual measures, and there is increased power to detect effects of the environment because errors of measurement decrease as scores are summed and degrees of freedom are preserved. This and similar cumulative environmental risk measures have been found to explain more variance in child and adolescent outcomes than single factor scores (Atzaba-Poria, et al. 2004; Bendersky and Lewis 1994; Bendersky and Lewis 1998; Deater-Deckard, et al. 1998; Sameroff, et al. 1993).

2.3.1.4. Father absence and stepfather-figure presence

Father absence was assessed based on the primary caregiver's response as to the presence or absence of each child's biological father in the home. Absence of biological father was coded as “1” whereas presence of biological father in the home was coded as “0”. A dichotomous variable for father absence/presence was created for each lab visit from age 11.0 through 13.5 and then averaged across the six age points.

Similarly, “stepfather-figure” presence in the home was also assessed at each lab visit (0=absent, 1=present), and these variables were averaged to create an overall score for stepfather-figure presence over the age range 11.0 to 13.5 years. Assessment of stepfather figure presence was based on the primary caregiver's endorsement of a partner, other than the child's biological father, living in the home. Note that absence of biological father and presence of stepfather-figure were coded as “1” as these conditions are both associated with early puberty in girls.

2.3.1.5. Maternal depressive symptoms

Maternal depressive symptoms were assessed using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck, et al. 1996), a well-validated measure of depressive symptomatology (Richter, et al. 1998). The BDI-II was administered to caregivers at the age 11.5 and 13.0 visits and scores were averaged over the two age points. This averaged score was then log-transformed to correct for skew.

2.3.2. Measures of Pubertal Development

2.3.2.1. Pubertal status and tempo

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS)(Petersen, et al. 1988) was computer-administered at each visit. The examiner stepped out of the room while the child read and listened to the questions read aloud by the computer. Computer assisted self-interview of potentially sensitive questions, including questions regarding pubertal status, has been shown to have a high degree of validity (Lamb, et al. 2011). The PDS contains 5 items assessing pubertal status, including the presence of a growth spurt, pubic hair, and skin changes for both boys and girls. For boys, PDS items also assess facial hair growth and voice change; for girls, items also assess breast development and menarche. Each item ranges from 1 (development has not yet begun) to 4 (development seems completed). The PDS correlates significantly with pubertal status based on physical exam (Brooks-Gunn, et al. 1987; Petersen, et al. 1988; Shirtcliff, et al. 2009). Pubertal tempo was assessed by examining the rate of change in pubertal status across age 11 to 13 years.

2.3.2.2. DHEA

DHEA was measured by obtaining a saliva sample (1 ml minimum) shortly after arrival to the research office at each visit. Participants were asked to drool through a straw into a small tube. Samples were immediately frozen for storage until they were shipped in dry ice to a laboratory for the cortisol assay.

Salivary DHEA was determined using a commercially available high sensitivity EIA kit (No. 1-1202/1-1212, Salimetrics) according to the manufacturer's directions. The range of this assay is 10-1000 pg.ml. Standard curves were fit by a weighted regression analysis using commercial software (Revelation 3.2) for the ELISA plate reader (Dynex MRX). From these curves, unknown values were computed. The antibody in this kit shows minimal cross reactivity (less than 0.001%) with other steroids present in the saliva. As many samples as practical were run in the same assay and participants were not split across different assay plates if possible. Laboratory controls were run on every plate for determination of inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variability, which were less than 8% for DHEA. The median correlation between DHEA and pubertal status across the six time points indicated that higher DHEA levels were modestly associated with more advanced pubertal status (r = 0.19, p = .03).

2.4. Data analysis

Group differences in pubertal status, DHEA, and study covariates as a function of PCE, sex, and their interaction were initially examined using analyses of variance (ANOVA) following multiple imputation of missing data (n = 20 data sets; SPSS version 20.0, IBM Corp., 2011). The effect of PCE and its potential interaction with both sex and child age on pubertal status and DHEA, controlling for the other risk factors, was then examined using mixed models analyses (Singer and Willett 2003) with an unstructured covariance matrix for the random effects. Given that children had a 12 month window in which to complete each lab visit, ages actually ranged from 11 to 14 years during the six assessments and as such age was treated as a continuous variable in the mixed models analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Pubertal Status as a Function of PCE and Sex

Table 1 presents estimated means and standard errors for pubertal status as a function of PCE and sex. PCE did not predict pubertal status in a series of univariate ANOVAs with the exception of at 13.0 years, when children with PCE exhibited lower pubertal status than unexposed children (F(1,187) = 6.53, p = .01).

Table 1. Estimated Means (and Standard Errors) of Pubertal Status and DHEA Levels by Cocaine Exposure and Sex.

| Cocaine Exposed | Unexposed | Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Cocaine | Sex | Coc × Sex | |

| (n = 36) | (n = 42) | (n = 64) | (n = 50) | F (1,187) | |||

| Pubertal status | |||||||

| 11.0 years | 2.02 (0.13) | 2.33 (0.13) | 2.05 (0.10) | 2.32 (0.12) | 0.18 | 7.93** | 0.08 |

| 11.5 years | 2.18 (0.13) | 2.45 (0.13) | 2.20 (0.11) | 2.38 (0.12) | 0.19 | 4.84* | 0.57 |

| 12.0 years | 2.21 (0.13) | 2.63 (0.13) | 2.38 (0.10) | 2.50 (0.12) | 0.22 | 2.49 | 0.39 |

| 12.5 years | 2.30 (0.13) | 2.70 (0.14) | 2.52 (0.10) | 2.68 (0.12) | 2.19 | 3.38† | 2.67 |

| 13.0 years | 2.27 (0.13) | 2.59 (0.15) | 2.93 (0.10) | 2.79 (0.12) | 6.53* | 0.52 | 1.48 |

| 13.5 years | 2.77 (0.15) | 2.97 (0.18) | 2.77 (0.12) | 2.94 (0.14) | 1.94 | 1.75 | 0.90 |

| DHEA levels | |||||||

| 11.0 years | 64.73 (7.93) | 106.30 (7.37) | 74.98 (5.98) | 94.70 (6.74) | 0.08 | 18.58*** | 2.44 |

| 11.5 years | 74.72 (10.12) | 104.77 (9.37) | 80.54 (7.51) | 99.87 (8.59) | 0.01 | 7.61** | 0.38 |

| 12.0 years | 70.63 (8.44) | 94.37 (7.80) | 84.99 (6.32) | 84.91 (7.10) | 0.12 | 2.53 | 2.59 |

| 12.5 years | 76.91 (8.36) | 120.44 (7.75) | 99.36 (6.29) | 89.91 (7.11) | 0.27 | 5.46* | 12.50** |

| 13.0 years | 99.22 (8.03) | 109.57 (7.54) | 114.05 (6.11) | 118.88 (6.86) | 2.79† | 1.22 | 0.16 |

| 13.5 years | 118.11 (8.91) | 135.47 (8.22) | 123.61 (6.66) | 126.23 (7.55) | 0.05 | 1.65 | 0.83 |

Note. Estimated means at a given age control for actual child age given minor age differences at each age point. In addition, estimated means for DHEA control for time since waking.

Mean variables computed from dichotomous variables; all values between 0 and 1.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.2. DHEA as a Function of PCE and Sex

Table 1 also presents estimated means and standard errors for DHEA levels as a function of PCE and sex, controlling for time since waking since DHEA levels decrease post-waking (Hucklebridge, et al. 2005). PCE exhibited a non-significant trend at 13.0 years as exposed children had lower DHEA levels than unexposed children (F(1,187) = 2.79, p = .097). PCE also interacted with sex at 12.5 years such that boys with PCE had lower DHEA levels whereas girls with PCE exhibited higher DHEA levels than their unexposed peers (F(1,187) = 12.50, p = .001).

3.3. Covariates as a Function of PCE and Sex

Table 2 presents estimated means and standard errors for covariates as a function of PCE and sex. PCE was associated with increased exposure to alcohol (F(1,187) = 22.51, p < .001), cigarettes (F(1,187) = 56.68, p < .001), and marijuana (F(1,187) = 5.17, p = .025) as well as greater environmental risk (F(1,187) = 4.61, p = .033) and biological father absence (F(1,187) = 4.40, p = .037). PCE also interacted with sex as girls, but not boys, in the sample were more likely to have experienced prenatal marijuana exposure (F(1,187) = 4.09, p = .045).

Table 2. Estimated Means (and Standard Errors) of Covariates by Cocaine Exposure and Sex.

| Cocaine Exposed | Unexposed | Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Cocaine | Sex | Coc × Sex | |

| (n = 36) | (n = 42) | (n = 64) | (n = 50) | F (1,187) | |||

| Covariates | |||||||

| Environmental risk | 3.74 (0.22) | 4.05 (0.21) | 3.22 (0.17) | 3.73 (0.19) | 4.61* | 4.21* | 0.28 |

| Maternal depressive symptoms | 6.06 (1.07) | 7.47 (1.00) | 7.04 (0.82) | 6.57 (0.91) | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.91 |

| Biological father absencea | 0.57 (0.07) | 0.55 (0.07) | 0.36 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.06) | 4.40* | 0.49 | 1.07 |

| Stepfather-figure presencea | 0.24 (0.06) | 0.24 (0.06) | 0.26 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.05) | 0.18 | 0.48 | 0.46 |

| Neonatal medical problems | 0.90 (0.32) | 1.52 (0.32) | 0.70 (0.26) | 0.43 (0.31) | 0.05 | 8.98** | 0.01 |

| Prenatal substance exposure | |||||||

| Alcohol (drinks/day) | 0.95 (0.31) | 1.71 (0.29) | 0.03 (0.23) | 0.02 (0.26) | 22.51*** | 1.73 | 1.90 |

| Cigarettes (per day) | 7.20 (1.08) | 9.68 (1.01) | 1.53 (0.80) | 0.98 (0.91) | 56.68*** | 1.08 | 2.60 |

| Cocaine (grams/day) | 0.39 (0.09) | 0.66 (0.08) | 0.00 (--) | 0.00 (--) | 56.08*** | 3.74† | 3.74† |

| Marijuana (joints/day) | 0.09 (0.15) | 0.57 (0.14) | 0.04 (0.14) | 0.00 (0.13) | 5.17* | 3.10† | 4.09* |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||||||

| 11.0 years | 20.44 (0.97) | 22.52 (0.90) | 22.57 (0.73) | 22.78 (0.82) | 1.78 | 1.83 | 1.51 |

| 11.5 years | 21.33 (0.91) | 23.20 (0.82) | 22.97 (0.70) | 23.97 (0.76) | 1.69 | 2.76 | 0.72 |

| 12.0 years | 22.24 (0.89) | 23.53 (0.83) | 22.73 (0.69) | 23.71 (0.76) | 0.25 | 2.11 | 0.08 |

| 12.5 years | 22.80 (0.86) | 24.01 (0.77) | 22.27 (0.64) | 24.47 (0.71) | 0.06 | 5.58* | 0.48 |

| 13.0 years | 23.26 (0.87) | 24.97 (0.82) | 22.83 (0.67) | 24.84 (0.75) | 0.12 | 6.06* | 0.03 |

| 13.5 years | 24.24 (0.94) | 26.39 (0.87) | 24.44 (0.71) | 26.44 (0.78) | 0.03 | 7.17** | 0.02 |

Note. Estimated means for BMI at a given age control for actual child age given minor age differences at each age point.

Mean values are computed from dichotomous variables; all values between 0 and 1.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < 001.

3.4. PCE as a Predictor of Pubertal Development, Controlling for Covariates

To examine whether PCE effects were present after controlling for covariates, two mixed models analyses were conducted with pubertal status and DHEA as the outcomes. Random effects were specified for the intercepts. PCE (exposed vs. unexposed), age (centered at 11.0 years using actual age at the time of the visit), environmental risk, neonatal medical problems, prenatal exposure to alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana, sex, and BMI were entered as covariates. In addition, interactions between PCE and sex were included to test whether exposure effects on pubertal status and DHEA differed for boys and girls. Similarly, interactions between PCE and age (centered) were examined to test whether PCE effects varied with age. The slope of change in pubertal status across age was used to measure pubertal tempo.

3.4.1. Preliminary analyses

Maternal depressive symptoms, biological father absence, and stepfather figure presence in the home were included with the other covariates in two preliminary mixed models analyses predicting pubertal status and DHEA. Interaction terms between child sex and father absence, and between sex and stepfather figure presence also were included as covariates because father absence and stepfather figure presence have been found to predict pubertal status only for girls. In addition, the three-way interaction among PCE, sex, and age also was included. None of these six covariates were found to predict pubertal status (p > 0.30) and were thus removed from the final pubertal status model to conserve statistical power. For DHEA, these covariates also did not approach significance (p > 0.20) with the exception of a non-significant trend for father absence (p = 0.09), which was thus retained in the final DHEA model. Maternal depressive symptoms, stepfather figure presence, and the interaction of each with sex was not significant and were dropped from the final DHEA model, as was the interaction of PCE by sex by age and the interaction of sex by age.

3.4.2. PCE and pubertal status

PCE was unrelated to pubertal status in the mixed models analysis (see Table 3). There was no specific time point between ages 11 and 14 at which exposed and unexposed children's pubertal status was significantly different when covariates were accounted for. The simple main effect of PCE at age 11 (as well as in models at age 12.0, 13.0, and 14.0) was not significant for boys or for girls, nor was there a significant PCE by sex interaction.

Table 3. Coefficients (Standard Error; 95% Confidence Intervals) from Mixed Model Analyses Predicting Pubertal Status and DHEA.

| Predictors | Pubertal Status | DHEA Level |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.92 (0.21; 1.51 to 2.32)*** | 62.06 (18.34; 29.02 to 101.33)*** |

| Age | 0.28 (0.03; 0.22 to 0.34)*** | 14.84 (3.38; 7.26 to 20.62)*** |

| Environmental risk | 0.01 (0.03; -0.06 to 0.07) | -1.30 (2.69; -6.87 to 3.77) |

| Neonatal medical problems | -0.06 (0.16; -0.39 to 0.26) | -4.40 (13.69; -30.52 to 23.59) |

| Prenatal substance exposure | ||

| Alcohol | -0.01 (0.05; -0.11 to 0.09) | -5.69 (3.96; -13.68 to 1.99) |

| Cigarettes | -0.04 (0.03; -0.11 to 0.03) | -3.97 (2.77; -9.17 to 1.79) |

| Cocaine | 0.11 (0.16; -0.21 to 0.43) | 38.95 (13.87; 17.31 to 72.09)** |

| Marijuana | -0.09 (0.07; -0.22 to 0.04) | -3.46 (5.37; -13.83 to 7.42) |

| Child sex | -0.19 (0.11; -0.40 to 0.02)† | -8.95 (8.69; -23.64 to 10.71) |

| Body Mass Index | 0.02 (0.01; 0.01 to 0.03)** | 1.97 (0.50; 0.81 to 2.77)*** |

| Prenatal cocaine exposure × sex | -0.06 (0.16; -0.38 to 0.27) | -19.83 (15.54; -67.39 to -6.03) |

| Prenatal cocaine exposure × age | -0.10 (0.05; -0.19 to -0.00)* | -12.26 (6.96; -32.89 to -5.37)* |

| Time since waking | -- | -2.24 (0.90; -4.09 to -0.55)* |

| Biological father absent | -- | -15.98 (8.15; -30.98 to 1.23)* |

Note. Cocaine exposure was entered as a dichotomous variable (0 = no exposure; 1 = exposed). Age was centered at 11.0 years.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. (2-tailed).

The simple main effect of age, as expected, was significant for both unexposed (t(98.70) = 9.32, p < .001) and exposed (t(76.95) = 4.56, p < .001) children, indicating that age was associated with more advanced pubertal status for participants in both groups. Greater BMI also was associated with more advanced pubertal status (t(326.59) = 3.01, p = .003). Environmental risk, neonatal medical problems, and other prenatal substance exposures did not predict pubertal status.

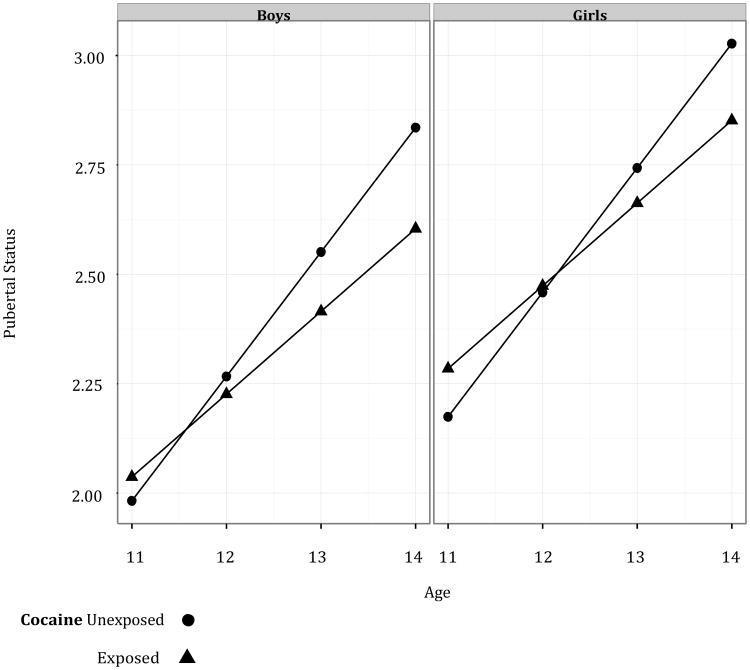

3.4.3. PCE and pubertal tempo

Pubertal tempo, as noted above, is the rate of change in pubertal status over time. As such, the presence of a PCE effect on pubertal tempo can be examined by testing for the presence of an interaction between PCE and age on pubertal status. The PCE by age interaction was significant, indicating that exposed children had slower rates of pubertal development (t(154.52) = 1.98, p = 0.050; see Table 3 and Figure 1). The pubertal status scores of exposed children were estimated to increase at a rate of only 0.19 per year compared to 0.28 per year for unexposed children after adjusting for covariates in the model.

Figure 1. Change in Pubertal Status over Time by Age for Boys and Girls.

3.4.4. PCE and DHEA levels

PCE predicted higher DHEA levels (t(165) = 3.03, p = .015). There was no specific time point, however, between ages 11 and 14 at which exposed and unexposed children's DHEA levels were significantly different when covariates were accounted for. Greater age (t(463) = 14.84, p < .001) and BMI also predicted higher DHEA levels (t(463) = 3.94, p < .001). Time since waking also was a significant covariate as participants tested closer to waking had higher DHEA levels (t(463) = 2.49, p = .013). In addition, children with an absent father had lower DHEA levels (t(165) = 2.05, p = .042). Environmental risk, neonatal medical problems, other prenatal substance exposures, sex, and the interaction of PCE and sex did not predict DHEA levels.

3.4.5. PCE and DHEA changes over time (DHEA tempo)

PCE interacted with age (t(463) = 2.31, p = 0.021; see Table 3). Specifically, exposed children's DHEA levels increased an average of only 4.90 per year, compared to 17.37 per year for unexposed children after adjusting for covariates in the model.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine pubertal status and pubertal tempo in adolescents prenatally exposed to cocaine. PCE was associated with slower pubertal tempo in early adolescence when controlling for covariates. The slower pubertal tempo associated with PCE was observed for both boys and girls as sex did not moderate the relationship between PCE and pubertal tempo. Consistent with the pubertal tempo findings, PCE also predicted a slower increase in DHEA levels from 11 to 13 years.

Our findings indicate that children with PCE experience a slower rate of pubertal development as measured by self-report during early adolescence. If this slower rate of development persists during mid-adolescence, children with PCE may experience delayed physical maturation relative to their unexposed peers. In addition, the lack of findings for cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana exposure in the current study support prior research in suggesting that the effects of prenatal substances on pubertal development may vary by substance. Contrary to the current findings, prenatal tobacco exposure has generally been associated with earlier pubertal status in prior research (Håkonsen, et al. 2014). In contrast, the finding that prenatal alcohol exposure did not predict pubertal status is consistent with earlier studies that also have found no effect for alcohol exposure on the timing of pubertal milestones (Shrestha, et al. 2011; Windham, et al. 2004). Likewise, prenatal marijuana exposure has been found to have no association with pubertal status (Fried, et al. 2001).

Examining teratogens more broadly, there is precedence for associations between potential teratogens and delayed pubertal development (Wu, et al. 2012). In addition to two studies finding prenatal tobacco exposure to predict later menarche (Ferris, et al. 2010; Windham, et al. 2008), prenatal exposure to dioxin and to tea in humans and prenatal exposure to lead in rats have been associated with later pubertal development (Dearth, et al. 2002; Korrick, et al. 2011; Windham, et al. 2004). There is further precedence in the animal literature for prenatal substance exposures to delay pubertal maturation, as well as to reduce fertility and sex organ function (Dearth, et al. 2002; Holloway, et al. 2006; Vahakangas, et al. 1985; Wenger, et al. 1988). While the underlying mechanisms for these findings remain unknown, the noradrenergic system may be involved. PCE has been shown to affect the noradrenergic system (Elsworth, et al. 2007; Foltz, et al. 2004; Seidler and Slotkin 1992; Snow, et al. 2004), which in turn may influence pubertal development. Norepinephrine plays a role in regulating the hypothalamus (Christman and Gisolfi 1985; Oishi 1979; Tsigos and Chrousos 2002), which contains cells that produce gonadotropin releasing hormones that regulate pubertal development, particularly the onset of puberty (Plant 2002). Accordingly, it is plausible to hypothesize a pathway wherein PCE acts to dysregulate the noradrenergic system, leading to dysregulation of the hypothalamus and subsequently affecting pubertal development. Alternatively, cocaine use during pregnancy has been found to increase maternal cortisol levels in animal studies, raising the possibility that increased fetal exposure to cortisol could lead to dysregulated HPA function, which in turn may be associated with alterations in pubertal timing (Ellis, et al. 2011; Lester and Lagasse 2010; Owiny, et al. 1991). Attenuated HPA function has recently been associated with accelerated pubertal tempo in girls (Saxbe, et al. 2014).

DHEA levels also increased more slowly among children with PCE. However, children exposed to cocaine had higher overall levels of DHEA. In the current study, DHEA was found to be modestly correlated with pubertal status, consistent with some prior research showing significant but inconsistent relations between DHEA and pubertal status (Matchock, et al. 2007). Considering the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system more broadly, cortisol levels have been found to increase in preparation for a perceived stressor such as coming to a research office visit, as was done in the current study (Kestler and Lewis 2009; Sullivan, et al. 2012). DHEA levels, however, have been found to decrease in response to such acute stress (Schwartz 2002), suggesting that increased stress reactivity by children with PCE at the time of DHEA collection does not explain their greater overall DHEA levels.

While there have been no prior reports on the effects of PCE on pubertal development or DHEA, animal studies have found PCE to be associated with differences in sexual behavior and gonadal hormones. Male rats prenatally exposed to cocaine show increased latency to initiate sexual behavior, as well as reduced scent marking and higher plasma luteinizing hormone (LH) levels, but no difference in testosterone levels which suggests a relative CNS insensitivity to androgens in these animals compared to controls (Raum, et al. 1990). In contrast, male rats with PCE were found to display shorter post-ejaculatory intromission intervals, suggesting enhanced sexual arousal, while exposed females showed reduced rearing, suggesting reduced sexual arousal (Vathy, et al. 1993). Norepinephrine and dopamine levels were higher in cocaine-exposed males in the preoptic area, a key brain area mediating steroid action on male sexual behavior (Vathy, et al. 1993). Similarly, perinatal cocaine exposure was found to reduce the volume of male rats' sexually dimorphic nucleus, which helps regulate sexual behavior (Maecker 1993). Collectively, these studies suggest that PCE affects perinatal androgenization, leading to changes in sexual behavior, gonadal hormones, and brain catecholamines that occur following pubertal development and highlight the potential importance of examining such measures in post-pubertal humans with PCE.

Several limitations of the current study deserve mention. First, our sample consists of predominantly African-American, urban children and as such our results may not generalize to other populations as, for example, African-American girls may experience earlier pubertal onset (Wu, et al. 2002). Second, our study assessed pubertal development from ages 11 to 13 as this is a time of great variability in pubertal status (Parent, et al. 2003), but it is unclear whether differences in pubertal status, tempo, or DHEA might be observed at earlier or later ages. Third, measures of prenatal alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana exposure were limited to self-report. PCE, which was confirmed by metabolite assay, was a dichotomous variable and as such did not allow for the examination of timing, continuity, or severity of exposure effects. Fourth, while the Pubertal Development Scale has been shown to be a valid measure of pubertal status (Brooks-Gunn, et al. 1987; Petersen, et al. 1988; Schmitz, et al. 2004), physician report (e.g., the Tanner Scale) may be a more sensitive, albeit difficult to obtain measure of pubertal development. Finally, repeated measurement of DHEA throughout the day (e.g., (Shirtcliff, et al. 2009) may provide a more valid measure of DHEA.

5. Conclusions

This study is the first to examine pubertal status and tempo in children with PCE. We found that children with PCE, while not showing significant differences in pubertal status during early adolescence, do show a slower pubertal tempo. Studies of pubertal tempo that examine psychosocial adjustment generally indicate that accelerated, not slower, tempo is a risk factor for greater adjustment problems (Ge, et al. 2003; Marceau, et al. 2011; Mendle, et al. 2010). Slower pubertal tempo, however, can be associated with health problems. For example, slow pubertal tempo may extend the window of vulnerability for breast carcinogenesis given prolonged exposure to endogenous hormones during a period of high mammary cell proliferation and differentiation (Ellis, et al. 2011). Furthermore, if this slower rate of pubertal development persists into mid-adolescence, children with PCE may lag behind their peers in pubertal status. Boys with late pubertal development have been found to exhibit increased rates of externalizing problems, substance use, and depressive symptoms (Graber, et al. 2004; Kaltiala-Heino, et al. 2003). These findings suggest that future research should examine the pubertal status of adolescents with PCE at older ages, as late pubertal development could mediate a potential relationship between PCE and adjustment problems in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Ms. #: NTT-14-40 Highlights.

Prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) was associated with slower pubertal tempo in early adolescence

PCE also was associated with smaller increases in DHEA in early adolescence

If these findings persist, children with PCE may be at-risk for delayed pubertal status at later ages

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant R01 DA007109 to Michael Lewis, David Bennett, and Dennis Carmody (MPI) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors greatly appreciate the statistical assistance of Charles Cleland.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

An earlier report of preliminary data from this study was presented at the Society for Research in Child Development biennial meeting, Denver, April, 2009.

Contributor Information

Jennifer M. Birnkrant, Email: Jennifmb@gmail.com.

Dennis P. Carmody, Email: Dennis.Carmody@Rutgers.edu.

Michael Lewis, Email: Lewis@RWJMS.Rutgers.edu.

References

- Ackerman JP, Riggins T, Black MM. A review of the effects of prenatal cocaine exposure among school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2010;125:554–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzaba-Poria N, Pike A, Deater-Deckard K. Do risk factors for problem behaviour act in a cumulative manner? An examination of ethnic minority and majority children through an ecological perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:707–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandstra ES, et al. Intrauterine growth of full-term infants: impact of prenatal cocaine exposure. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1309–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.6.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman DA, Chiriboga CA. Dose-response effect of cocaine on newborn head circumference. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):E33. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.3.e33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, et al. Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development. 2007;78:1302–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Bennett DS, Lewis M. Aggression at age 5 as a function of prenatal exposure to cocaine, gender, and environmental risk. J Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:71–84. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Lewis M. Environmental risk, biological risk and developmental outcome. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(4):484–494. [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Lewis M. Arousal modulation in cocaine-exposed infants. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(3):555–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky M, Lewis M. Prenatal Cocaine Exposure and Neonatal Condition. Infant Behavior & Development. 1999;22(3):353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Bendersky M, Lewis M. Preadolescent health risk behavior as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and gender. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:467–72. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811320d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Bendersky M, Lewis M. Children's cognitive ability from 4 to 9 years old as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure, environmental risk, and maternal verbal intelligence. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:919–928. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, et al. Externalizing problems in late childhood as a function of prenatal cocaine exposure and environmental risk. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(3):296–308. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, et al. Validity of self-report measures of girls' pubertal status. Child Dev. 1987;58(3):829–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody DP, Bennett DS, Lewis M. The effects of prenatal cocaine exposure and gender on inhibitory control and attention. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2011;33(1):61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman JV, Gisolfi CV. Heat acclimation: role of norepinephrine in the anterior hypothalamus. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1985;58(6):1923–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1985.58.6.1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagnone NA, Mellon SH. Dehydroepiandrosterone: a potential signalling molecule for neocortical organization during development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(8):4678–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aloisio Aimee A, et al. Prenatal and infant exposures and age at menarche. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2013;24(2):277. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31828062b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearth RK, et al. Effects of lead (Pb) exposure during gestation and lactation on female pubertal development in the rat. Reproductive Toxicolology. 2002;16:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(02)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, et al. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–93. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: an integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:920–58. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Garber J. Psychosocial antecedents of variation in girls' pubertal timing: maternal depression, stepfather presence,and marital and family stress. Child Development. 2000;71(2):485–501. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, et al. Quality of early family relationships and the timing and tempo of puberty: effects depend on biological sensitivity to context. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:85–99. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsworth JD, et al. Prenatal cocaine exposure enhances responsivity of locus coeruleus norepinephrine neurons: role of autoreceptors. Neuroscience. 2007;147:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst A, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and reproductive health of daughters: a follow-up study spanning two decades. Human reproduction. 2012;27(12):3593–3600. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler FD, et al. Birth outcome from a prospective, matched study of prenatal crack/cocaine use: I. Interactive and dose effects on health and growth. Pediatrics. 1998;101(2):229–37. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris JS, et al. Prenatal and childhood environmental tobacco smoke exposure and age at menarche. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2010;24:515–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltz TL, et al. Prenatal intravenous cocaine and the heart rate-orienting response: a dose-response study. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2004;22:285–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, James DS, Watkinson B. Growth and pubertal milestones during adolescence in offspring prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23(5):431–6. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, et al. It's about timing and change: pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):430–9. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, et al. Is pubertal timing associated with psychopathology in young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:718–26. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewen Karen, et al. Prenatal cocaine effects on brain structure in early infancy. NeuroImage. 2014;101:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkonsen Linn Berger, Ernst Andreas, Ramlau-Hansen Cecilia Høst. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and reproductive health in children: a review of epidemiological studies. Asian journal of andrology. 2014;16(1):39. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.122351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock JC, Auchus RJ, Rainey WE. The rise in adrenal androgen biosynthesis: adrenarche. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 2004;22:337–47. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q, Karlberg J. Bmi in childhood and its association with height gain, timing of puberty, and final height. Pediatric Research. 2001;49(2):244–51. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200102000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobel CJ, et al. Prenatal and intrapartum high-risk screening. I. Prediction of the high-rish neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;117(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway AC, Kellenberger LD, Petrik JJ. Fetal and neonatal exposure to nicotine disrupts ovarian function and fertility in adult female rats. Endocrine. 2006;30:213–6. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:30:2:213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hucklebridge Frank, et al. The diurnal patterns of the adrenal steroids cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in relation to awakening. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulanicka B. Acceleration of menarcheal age of girls from dysfunctional families. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1999;17(2):119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hulanicka B, Gronkiewicz L, Koniarek J. Effect of familial distress on growth and maturation of girls: a longitudinal study. American Journal of Human Biology. 2001;13:771–6. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Kosunen E, Rimpela M. Pubertal timing, sexual behaviour and self-reported depression in middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(5):531–45. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplowitz PB. Link between body fat and the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S208–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestler L, et al. Gender-Dependent Effects of Prenatal Cocaine Exposure. In: Kestler L, Lewis M, editors. Gender Differences in Prenatal Substance Exposure. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kestler LP, Lewis M. Cortisol response to inoculation in 4-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(5):743–51. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Smith PK. Retrospective Survey of Parental Marital Relations and Child Reproductive Development. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22(4):729–751. [Google Scholar]

- Korrick SA, et al. Dioxin exposure and age of pubertal onset among Russian boys. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119:1339–44. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmer Tina, Oliver Bonamy R, Maughan Barbara. Pubertal development, spare time activities, and adolescent delinquency: Testing the contextual amplification hypothesis. Journal of youth and adolescence. 2013:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb MM, et al. Feasibility of an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview method to self-assess sexual maturation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert BL, Bauer CR. Developmental and behavioral consequences of prenatal cocaine exposure: a review. Journal of Perinatology. 2012;32(11):819–828. doi: 10.1038/jp.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, et al. Prenatal cocaine exposure related to cortisol stress reactivity in 11-year-old children. J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):288–295 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester Barry M, Lagasse Linda L. Children of addicted women. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2010;29(2):259–276. doi: 10.1080/10550881003684921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutiger B, et al. Relationship between gestational cocaine use and pregnancy outcome: a meta-analysis. Teratology. 1991;44:405–14. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maecker Heather L. Perinatal cocaine exposure inhibits the development of the male SDN. Developmental brain research. 1993;76(2):288–292. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90221-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonet Mildred, et al. Role of prenatal characteristics and early growth on pubertal attainment of British girls. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e591–e600. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marceau K, et al. Individual differences in boys' and girls' timing and tempo of puberty: modeling development with nonlinear growth models. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1389–409. doi: 10.1037/a0023838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matchock RL, Dorn LD, Susman EJ. Diurnal and seasonal cortisol, testosterone, and DHEA rhythms in boys and girls during puberty. Chronobiology International. 2007;24:969–90. doi: 10.1080/07420520701649471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J. Beyond pubertal timing: new directions for studying individual differences in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, et al. Development's tortoise and hare: pubertal timing, pubertal tempo, and depressive symptoms in boys and girls. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1341–53. doi: 10.1037/a0020205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnes S, et al. Dysmorphic and anthropometric outcomes in 6-year-old prenatally cocaine-exposed children. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2006;28:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moe V, Slinning K. Children prenatally exposed to substances: Gender-related differences in outcome from infancy to 3 years of age. Infant Mental Health. 2001;22(3):334–350. [Google Scholar]

- Morris DH, et al. Determinants of age at menarche in the UK: analyses from the Breakthrough Generations Study. British journal of cancer. 2010;103(11):1760–1764. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbeck JS, Lindsey AM, Carrieri VL. The development of an instrument to measure social support. Nursing Research. 1981;30(5):264–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi T. Possible role of brain norepinephrine in the hypothalamic hypophyseal adrenal system. Endocrinologia Japonica. 1979;26(3):399–409. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.26.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr ST, James SA, Casper R. Psychosocial stressors and low birth weight: development of a questionnaire. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1992;13(5):343–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owiny JR, et al. Cocaine in pregnancy: The effect of maternal administration of cocaine on the maternal and fetal pituitary-adrenal axes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1991;164(2):658–663. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(11)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimas J. Adrenarche. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1997;816:57–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent AS, et al. The timing of normal puberty and the age limits of sexual precocity: variations around the world, secular trends, and changes after migration. Endocrine Reviews. 2003;24(5):668–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, et al. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TM. Neurophysiology of puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(6 Suppl):185–91. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proos LA, et al. Increased perinatal intracranial pressure and brainstem dysfunction predict early puberty in boys with myelomeningocele. Acta Paediatrica. 2011;100:1368–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao H, et al. Altered resting cerebral blood flow in adolescents with in utero cocaine exposure revealed by perfusion functional MRI. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1245–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raum WJ, et al. Prenatal inhibition of hypothalamic sex steroid uptake by cocaine: effects on neurobehavioral sexual differentiation in male rats. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1990;53(2):230–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravnborg TL, et al. Prenatal and adult exposures to smoking are associated with adverse effects on reproductive hormones, semen quality, final height and body mass index. Human Reproduction. 2011;26:1000–11. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, Goldschmidt L, Larkby C. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on growth: a longitudinal analysis. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1017–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GA, et al. Growth of infants prenatally exposed to cocaine/crack: comparison of a prenatal care and a no prenatal care sample. Pediatrics. 1999;104(2):e18. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson Gale A, et al. Effects of prenatal cocaine exposure on child behavior and growth at 10years of age. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2013;40:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter P, et al. On the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A review. Psychopathology. 1998;31(3):160–8. doi: 10.1159/000066239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin C, et al. Timing of maturation and predictors of menarche in girls enrolled in a contemporary British cohort. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2009;23:492–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, et al. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: the influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64(1):80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe DE, Repetti RK. Brief report: Fathers' and mothers' marital relationship predicts daughters' pubertal development two years later. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;32(2):415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxbe Darby E, et al. Attenuated hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis functioning predicts accelerated pubertal development in girls 1 year later. Development and psychopathology. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz KE, et al. A validation study of early adolescents' pubertal self-assessments. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2004;24(4):357–384. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KE. Autoimmunity, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and stress. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(4 Suppl):37–43. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Fetal cocaine exposure causes persistent noradrenergic hyperactivity in rat brain regions: effects on neurotransmitter turnover and receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263(2):413–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankaran S, et al. Prenatal cocaine exposure and BMI and blood pressure at 9 years of age. J Hypertens. 2010;28(6):1166–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Dahl RE, Pollak SD. Pubertal development: correspondence between hormonal and physical development. Child Development. 2009;80(2):327–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff E, et al. Salivary dehydroepiandrosterone responsiveness to social challenge in adolescents with internalizing problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2007;48:580–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha A, et al. Smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy and age of menarche in daughters. Human Reproduction. 2011;26:259–65. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Snow DM, et al. Cocaine-induced inhibition of process outgrowth in locus coeruleus neurons: role of gestational exposure period and offspring sex. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2004;22:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulcova J, et al. Age and sex related differences in serum levels of unconjugated dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulphate in normal subjects. Journal of Endocrinology. 1997;154(1):57–62. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1540057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MW, Bennett DS, Lewis M. Individual Differences in the Cortisol Responses of Neglected and Comparison Children. Child Maltreat. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1077559512449378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tither JM, Ellis BJ. Impact of fathers on daughters' age at menarche: a genetically and environmentally controlled sibling study. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1409–20. doi: 10.1037/a0013065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):865–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahakangas K, Rajaniemi H, Pelkonen O. Ovarian toxicity of cigarette smoke exposure during pregnancy in mice. Toxicology Letters. 1985;25(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(85)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vathy I, Katay L, Mini KN. Sexually dimorphic effects of prenatal cocaine on adult sexual behavior and brain catecholamines in rats. Brain Research Developmental Brain Research. 1993;73(1):115–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90053-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner TD, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of frontal white matter and executive functioning in cocaine-exposed children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2014–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger T, Croix D, Tramu G. The effect of chronic prepubertal administration of marihuana (delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol) on the onset of puberty and the postpubertal reproductive functions in female rats. Biology of Reproduction. 1988;39(3):540–5. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.3.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windham GC, et al. Age at menarche in relation to maternal use of tobacco, alcohol, coffee, and tea during pregnancy. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(9):862–71. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windham GC, et al. Maternal smoking, demographic and lifestyle factors in relation to daughter's age at menarche. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2008;22:551–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfahrt-Veje C, et al. Smaller genitals at school age in boys whose mothers were exposed to non-persistent pesticides in early pregnancy. International Journal of Andrology. 2012a;35:265–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2012.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfahrt-Veje C, et al. Early breast development in girls after prenatal exposure to non-persistent pesticides. Internatoinal Journal of Andrology. 2012b;35:273–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2011.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Tiejian, Mendola P, Buck Germaine M. Ethnic differences in the presence of secondary sex characteristics and menarche among US girls: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):752–757. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.4.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Zhang N, Lee MM. The influence of endocrine disruptors on male pubertal timing. In: Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Gore A, editors. Endocrine disruptors and puberty. New York: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 339–355. Contemporary Endocrinology. [Google Scholar]