Abstract

Background

While several studies have shown a high association between cannabis use and use of other illicit drugs, the predictors of progression from cannabis to other illicit drugs remain largely unknown. This study aims to estimate the cumulative probability of progression to illicit drug use among individuals with lifetime history of cannabis use, and to identify predictors of progression from cannabis use to other illicit drugs use.

Methods

Analyses were conducted on the sub-sample of participants in Wave 1of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) who started cannabis use before using any other drug (n= 6,624). Estimated projections of the cumulative probability of progression from cannabis use to use of any other illegal drug use in the general population were obtained by the standard actuarial method. Univariate and multivariable survival analyses with time-varying covariates were implemented to identify predictors of progression to any drug use.

Results

Lifetime cumulative probability estimates indicated that 44.7% of individuals with lifetime cannabis use progressed to other illicit drug use at some time in their lives. Several sociodemographic characteristics, internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders and indicators of substance use severity predicted progression from cannabis use to other illicit drugs use.

Conclusion

A large proportion of individuals who use cannabis go on to use other illegal drugs. The increased risk of progression from cannabis use to other illicit drugs use among individuals with mental disorders underscores the importance of considering the benefits and adverse effects of changes in cannabis regulations and of developing prevention and treatment strategies directed at curtailing cannabis use in these populations.

Keywords: gateway, progression, cannabis, other illicit drugs

1. INTRODUCTION

The gateway hypothesis holds that substance use progresses in sequential stages beginning with alcohol and tobacco use, followed by cannabis use and, later, the use of other illicit drugs (Kandel, 1975, 2003; Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992; Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Klein, 2006). According to the gateway hypothesis, individuals rarely use certain substances, such as heroin or cocaine, without having first used “gateway” substances, such as legal drugs or cannabis. The validity of the gateway hypothesis has been the topic of intense debate since the early 1970s. Although some studies have found that use of legal drugs or cannabis are not a requirement for the progression to other illicit drugs (Golub & Johnson, 1994; Mackesy-Amiti, Fendrich, & Goldstein, 1997; Malone, Lamis, Masyn, & Northrup, 2010; Morral, McCaffrey, & Paddock, 2002; Tarter et al., 2012; Tarter, Vanyukov, Kirisci, Reynolds, & Clark, 2006), most studies have supported the “gateway sequence” (Degenhardt et al., 2009; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2006; Fergusson & Horwood, 2000; Grau et al., 2007; Makanjuola, Oladeji, & Gureje, 2010; Mayet, Legleye, Falissard, & Chau, 2012; Rebellon & Van Gundy, 2006; Van Ours, 2003; Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1984).

In recent years there has been a growing interest in the effects of cannabis on mental health and psychosocial functioning (Blanco et al., 2014; Copeland, Rooke, & Swift, 2013; Moore et al., 2007; van Gastel et al., 2013; Van Ours & Williams, 2012), including the extent to which cannabis acts as a ‘gateway drug’ (Fergusson et al., 2006; Vanyukov et al., 2012). Cannabis would meet the conditions for gateway drug if (a) its use was initiated prior to the onset of other illicit drug use; and, (b) cannabis use increased the likelihood of using other illicit drugs (Fergusson et al., 2006).

While most of the studies have shown a high degree of association between cannabis use and use of other illicit drugs (Agrawal, Neale, Prescott, & Kendler, 2004; Fergusson & Horwood, 2000; Khan et al., 2013; Lynskey et al., 2003; O’Donnell & Clayton, 1982; Van Ours, 2003), the predictors of progression from cannabis to other illicit drugs remain largely unknown (Kandel et al., 2006; Van Gundy & Rebellon, 2010). Identification of those predictors is a crucial step in understanding the etiology of substance use disorders that could help in the development of more effective treatment and preventive interventions.

Prior research has indicated that genetic predisposition (Agrawal et al., 2004), higher frequency of cannabis use (Fergusson & Horwood, 2000; Mayet et al., 2012) and early onset of cannabis use (Fergusson et al., 2006; Van Gundy & Rebellon, 2010) are associated with increased risk of progression to other illicit drug use. Presence of depressive symptoms (Yamaguchi & Kandel, 1984), stress and unemployment (Van Gundy & Rebellon, 2010), peer influence (Wagner & Anthony, 2002) or drug availability (Degenhardt et al., 2010) have also been linked to increased risk of progression to other illicit drug use. Despite this body of knowledge, important questions remain regarding predictors of progression from cannabis use to use of other drugs (Kandel et al., 2006). For example, several sociodemographic, psychopathologic and substance use related predictors previously reported for other types of drug use transitions (Florez-Salamanca et al., 2013; Lopez-Quintero, Perez de los Cobos, et al., 2011; Ridenour, Maldonado-Molina, Compton, Spitznagel, & Cottler, 2005) have not been examined. With the exception of one study that examined depression, no published study has investigated the effect of psychiatric comorbidity (i.e., anxiety, conduct or personality disorders) on progression from cannabis use to use of other drugs.

We sought to build on prior work by drawing on data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large nationally representative study of the United States (US) adult population (Grant & Kaplan, 2005). The main goals of this study were to: 1) estimate the cumulative probability of progression to illicit drug use among individuals with lifetime history of cannabis use; and, 2) assess the association between several sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidity and substance use-related variables and the risk of progression from cannabis use to other illicit drugs use.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample

The NESARC target population at Wave 1 (2001-2002) was the civilian non-institutionalized population 18 years and older residing in households and group quarters. The final sample included 43,093 respondents. Blacks, Hispanics, and adults 18-24 were oversampled, with data adjusted for oversampling, household- and person-level non-response. The overall survey response rate was 81%. Data were adjusted using the 2000 Decennial Census, to be representative of the US civilian population for a variety of sociodemographic variables. Interviews were conducted by experienced lay interviewers with extensive training and supervision (Grant et al., 2009; Grant, Hasin, et al., 2004). All procedures, including informed consent, received full human subjects review and approval from the US Census Bureau and US Office of Management and Budget. This study examined data of the sub-sample of individuals who started cannabis use at Wave 1 before using any other drug (n= 6,624). Those who used other illicit drug before cannabis (n= 484) and those who only used other illicit drug (n=964) were not included in the current analyses.

Data were collected using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM-IV (AUDADIS-IV) (Grant et al., 2003). The AUDADIS-IV is a structured diagnostic interview, developed to advance measurement of substance use and mental disorders in large-scale surveys (Grant, Stinson, et al., 2004). Computer algorithms produced DSM-IV diagnoses based on AUDADIS-IV data.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic factors included gender, self-reported age, race/ethnicity (Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians and Native Americans), urbanicity (urban vs. rural), nativity (U.S.-born vs. foreign-born), educational attainment, marital status and employment status. Family history of substance use disorders (SUD) was defined as any alcohol or drug use disorder among first degree relatives (Heiman, Ogburn, Gorroochurn, Keyes, & Hasin, 2008).

2.2.2. Substance use, abuse and dependence

Extensive AUDADIS-IV questions covered DSM-IV criteria for nicotine, alcohol and cannabis use disorders. For nicotine and alcohol dependence, 3 or more of 7 criteria within a 12-month period are required. The diagnosis of cannabis dependence required that at least 3 criteria from a list of six during a 12-month period be met. Because DSM-IV does not describe a withdrawal syndrome for cannabis, the AUDADIS-IV withdrawal criterion was not included in the diagnosis of cannabis dependence. For alcohol and cannabis abuse, participants had to meet 1 or more of 4 criteria within a 12-month period and not meet the criteria for dependence (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Age of substance use onset was determined by asking respondents about the age at which they first used: cannabis, sedatives, tranquilizers, analgesics, stimulants, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other. Consistent with prior reports (Blanco et al., 2007; Blanco et al., 2013; Martins et al., 2012) non-medical use of a prescription drug was defined to respondents as using a prescription drug (sedatives, tranquilizers, analgesics, and stimulants) “without a prescription, in greater amounts, more often, or longer than prescribed, or for a reason other than a doctor said you should use them”. After the initial probe item, the respondent was given an extensive list of examples of prescription drugs and asked if s/he used any of the prescription drugs on the list or similar drugs ‘nonmedically’. The good to excellent test-retest reliability and validity of AUDADIS-IV SUD diagnoses is well documented in clinical and general population samples (Grant et al., 2003; Ruan et al., 2008).

2.2.3. Psychiatric disorders

Mood disorders included DSM-IV primary major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar I and II disorders. Anxiety disorders included DSM-IV panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia and generalized anxiety disorder. AUDADIS-IV methods to diagnose these disorders are described in detail elsewhere (Grant, Hasin, et al., 2004; Grant et al., 2005; Hasin, Goodwin, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Stinson et al., 2007). Avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, histrionic and antisocial personality disorders were assessed on a lifetime basis at Wave 1 and described in detail elsewhere (Grant, Hasin, et al., 2004).

Test-retest reliabilities for AUDADIS-IV mood, anxiety and personality disorders diagnoses in the general population and clinical settings were fair to good (κ=0.40-0.77) (Canino et al., 1999; Grant et al., 2003; Ruan et al., 2008). Convergent validity was good to excellent for all affective, anxiety, and personality disorders diagnoses (Grant, Hasin, et al., 2004; Hasin et al., 2005) and selected diagnoses showed good agreement (κ=0.64-0.68) with psychiatrist reappraisals (Canino et al., 1999).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Weighted frequencies and their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were computed to characterize the sample. Estimated projections of the cumulative probability of progression from cannabis use to any drug use in the general population were obtained by the standard actuarial method (Machin, Cheung, & Parmar, 2006) as implemented in PROC LIFETEST in SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). This method, which is often used in the analysis of cross-sectional data (Lopez-Quintero, Hasin, et al., 2011; Lopez-Quintero, Perez de los Cobos, et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2005), allows to estimate retrospectively the time of events (in this case onset of cannabis use) and use that information to project future cumulative rates (Hosmer, Lemehsow, & May, 2008). Individuals who started using other drugs prior to using cannabis (18.9% of lifetime cannabis users) were not included in these analyses.

Univariate and multivariable survival analyses with time-varying variables (with person-year as the unit of analysis) (Jenkins, 1995) were implemented using SUDAAN version 9.1, (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park). In accord with established recommendations (Hosmer et al., 2008), only variables that were significant in the bivariate analyses at p ≤0.20 were included in the multivariable model. These unadjusted and adjusted models aimed at assessing the association between sociodemographic, psychiatric comorbidity and substance use-related covariates and the hazards of progression from cannabis use to use of any other drug. The person-year variable was defined as the number of years from cannabis use onset to any drug use onset or age at Wave 1 interview (for censored cases). Educational attainment, marital status, and presence of DSM-IV mood, anxiety, and nicotine, alcohol and cannabis disorders were included as time-dependent variables. Modeling psychiatric disorders as time-varying variables ensured that the disorders always preceded the transition from cannabis use to use of other illicit drugs and thus could be considered predictors and not consequences of the use of those drugs.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Probability of progression from cannabis use to any other illicit drug use

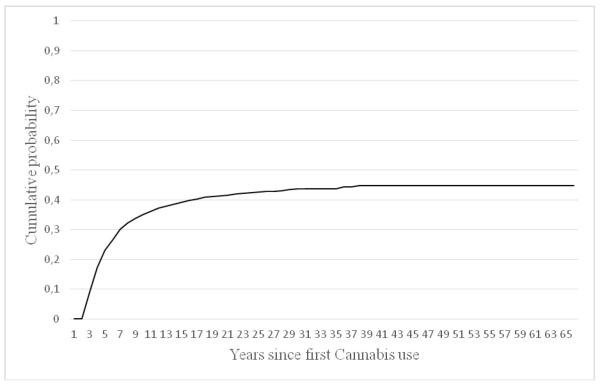

Lifetime cumulative probability estimates indicated that 44.7%of individuals with lifetime cannabis use progressed to other illicit drug use at some time in their lives. During the second year after first cannabis use, the probability of other illicit drug initiation was 8.7%. The estimated cumulative probability of other illicit drug initiation a decade after the onset of cannabis use was 36% (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative probability of other illicit drug use initiation among individuals with lifetime history of cannabis use

3.2. Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1. Despite similar percentage and CI between 18-29 and 30-44 age groups, we found statistical significant differences between both groups (p< 0.005). The majority of respondents who progressed to other illicit drug use were male, between 30 and 44 years old, US-born, urban people, and had less than high school education.

Table1.

Proportion of individuals with lifetime cannabis used who progressed to the use of other illicit drugs, by sociodemographic characteristics

| Characteristics | Any Drug Use a (n=2572) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95%CIb | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 42.71 | 40.65 | 44.80 |

| Female | 34.98 | 32.82 | 37.20 |

| Age group | |||

| 18-29 | 38.53 | 35.56 | 41.60 |

| 30-44 | 43.75 | 41.49 | 46.04 |

| ≥45 | 33.25 | 30.53 | 36.08 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Whites | 40.54 | 38.82 | 42.28 |

| Blacks | 25.17 | 22.02 | 28.60 |

| Hispanics | 43.07 | 38.64 | 47.61 |

| Asians | 43.68 | 34.74 | 53.06 |

| Native American | 47.87 | 39.25 | 56.62 |

| Urbanicity | |||

| Rural | 36.11 | 32.67 | 39.69 |

| Urban | 40.05 | 38.28 | 41.85 |

| US Born | |||

| Yes | 39.76 | 38.12 | 41.41 |

| No | 32.36 | 27.06 | 38.16 |

| Education | |||

| < High school | 43.25 | 38.64 | 47.97 |

| High school | 39.58 | 36.42 | 42.84 |

| ≥ College | 38.70 | 36.89 | 40.55 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married/living with someone | 37.57 | 35.57 | 39.62 |

| Divorced/separated | 43.10 | 39.41 | 46.87 |

| Widowed | 33.51 | 22.24 | 47.04 |

| Never married | 41.63 | 38.66 | 44.66 |

| Employment status | |||

| Ever employed | 39.93 | 38.17 | 41.73 |

| Never employed | 37.40 | 34.40 | 40.50 |

Sedatives, tranquilizers, painkillers, stimulants, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other,

95% confidence interval.

3.3. Psychiatric and substance use comorbid disorders

Psychiatric comorbid disorders and other substance use-related characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 2. Among individuals with any drug use who had Axis I disorder, a mood disorder, an anxiety disorder, a lifetime history of conduct disorder, a personality disorder, nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder, or cannabis use disorder, about 50% started cannabis use before using any other drug. Of those with a family history of SUD,almost 45% progress to use another illicit drug. The mean age of first use of cannabis was 16.1 years (SD=3.52; range: 5-45) and the mean age of first use of other illicit drugs was 20.61 (SD=6.34; range: 8-58).

Table 2.

Proportion of individuals with life cannabis who progressed to the use of other illicit drugs, by presence of psychiatric disorders

| Characteristics | Any Drug Use a (n=2572) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95%CIb | ||

| Any Axis I disorder | |||

| Yes | 43.22 | 41.54 | 44.93 |

| No | 16.82 | 13.87 | 20.26 |

| Any mood disorder | |||

| Yes | 48.76 | 45.97 | 51.56 |

| No | 35.61 | 33.73 | 37.54 |

| Any anxiety disorder | |||

| Yes | 47.44 | 44.23 | 50.67 |

| No | 36.72 | 34.99 | 38.49 |

| Any conduct disorder | |||

| Yes | 40.34 | 29.58 | 52.12 |

| No | 39.37 | 37.77 | 41.00 |

| Any personality disorder | |||

| Yes | 50.68 | 47.87 | 53.48 |

| No | 34.08 | 32.28 | 35.92 |

| Family history of SUD | |||

| Yes | 44.68 | 42.58 | 46.79 |

| No | 33.18 | 31.03 | 35.39 |

| Nicotine Dependence | |||

| Yes | 51.97 | 49.35 | 54.58 |

| No | 31.98 | 30.12 | 33.90 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | |||

| Yes | 47.08 | 45.07 | 49.11 |

| No | 24.83 | 22.56 | 27.26 |

| Cannabis Use Disorder | |||

| Yes | 56.35 | 53.74 | 58.93 |

| No | 28.92 | 27.20 | 30.71 |

| Age first used cannabis (continuous, mean) | 16.15 | 15.97 | 16.33 |

| Age first used OIDc (continuous, mean) | 20.61 | 20.29 | 20.94 |

Sedatives, tranquilizers, painkillers, stimulants, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other,

95% confidence interval,

other illicit drugs.

3.4. Predictors of progression from cannabis use to any other illicit drug use

In univariate (Table 3) and multivariable (Table 4) survival models, several sociodemographic, psychopathological and substance use-related variables predicted progression from cannabis use to other illicit drug use.

Table 3.

Predictors of progression from cannabis use to other drug use among individuals with lifetime cannabis use preceding lifetime use of other drugs at NESARC wave 1. Univariate results of survival analyses

| Characteristics | Any Drug Usea | (n=2572) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HRb | 95%CIc | p | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 1.28 | 1.17 | 1.40 | 0.000 |

|

| ||||

| Age group | ||||

|

| ||||

| 18-29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| 30-44 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.098 |

|

| ||||

| ≥45 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 1.04 | 0.155 |

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Black | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 1.000 |

| Asian | 1.14 | 0.82 | 1.58 | 0.451 |

| Native American | 1.19 | 0.90 | 1.57 | 0.229 |

|

| ||||

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Rural | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.075 |

| Urban | 1.12 | 0.99 | 1.28 | |

|

| ||||

| US Born | ||||

| Yes | 1.20 | 0.94 | 1.53 | 0.136 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 0.94 | 0.75 | 1.17 | 0.575 |

| High school | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.446 |

| ≥ College | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Divorced/separated | 2.06 | 1.59 | 2.67 | 0.000 |

| Widowed | 2.11 | 0.57 | 7.78 | 0.262 |

| Never married | 2.19 | 1.84 | 2.60 | 0.000 |

|

| ||||

| Employment status | ||||

| Ever employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Never employed | 1.00 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 0.953 |

|

| ||||

| Any Axis I disorder | ||||

| Yes | 2.30 | 2.07 | 2.57 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Mood disorder | ||||

| Yes | 1.67 | 1.45 | 1.93 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Anxiety disorder | ||||

| Yes | 1.29 | 1.13 | 1.46 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Conduct disorder | ||||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.67 | 1.43 | 0.905 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Personality disorder | ||||

| Yes | 1.55 | 1.38 | 1.74 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Family history of SUD | ||||

| Yes | 1.33 | 1.21 | 1.47 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Nicotine Dependence | ||||

| Yes | 2.01 | 1.75 | 2.32 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | ||||

| Yes | 1.97 | 1.78 | 2.19 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Cannabis Use Disorder | ||||

| Yes | 2.74 | 2.46 | 3.05 | 0.000 |

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

|

| ||||

| Age first used cannabis (continuous) | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.000 |

Sedatives, tranquilizers, analgesics, stimulants, cocaine/crack, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other,

hazard ratio,

95% confidence interval.

Predictors included as time-dependent variables: Education, marital status, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder and cannabis use disorder.

Table 4.

Predictors of progression from cannabis use to other drug use among individuals with lifetime cannabis use preceding lifetime use of other drugs in the NESARC wave 1. Multivariate results of survival analyses

| Characteristic |

Any Drug

Usea (n=2572) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR b | 95%CI c | ||

| Gender | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 1.23 | 1.09 | 1.36 |

|

| |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.55 |

| Hispanic | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.13 |

| Asian | 1.20 | 0.81 | 1.77 |

| Native American | 0.96 | 0.70 | 1.31 |

|

| |||

| Urbanicity | |||

| Rural | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Urban | 1.19 | 1.02 | 1.36 |

|

| |||

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Divorced/separated | 1.94 | 1.49 | 2.54 |

| Widowed | 1.97 | 0.46 | 8.41 |

| Never married | 2.15 | 1.79 | 2.58 |

|

| |||

| Mood disorder | 1.33 | 1.12 | 1.57 |

|

| |||

| Anxiety disorder | 1.17 | 1.01 | 1.36 |

|

| |||

| Personality disorder | 1.34 | 1.17 | 1.53 |

|

| |||

| Family history of SUD | 1.28 | 1.15 | 1.43 |

|

| |||

| Nicotine Dependence | 1.58 | 1.35 | 1.86 |

|

| |||

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 1.53 | 1.36 | 1.72 |

|

| |||

| Cannabis Use Disorder | 2.33 | 2.06 | 2.62 |

| Age first used cannabis (continuous) | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.97 |

Sedatives, tranquilizers, analgesics, stimulants, cocaine or crack, hallucinogens, inhalants/solvents, heroin, and other,

hazard ratio,

95% confidence interval.

Predictors included as time-dependent variables: Education, marital status, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder and cannabis use disorder.

3.4.1. Sociodemographic predictors

As shown in the adjusted models (Table 4) males were more likely than females to progress from cannabis use to other illicit drug use (HR=1.23, 95% CI = 1.09-1.36). Compared to White cannabis users, Blacks were less likely to progress to other illicit drug use (HR=0.46, 95% CI =0.39-0.55). Individuals living in urban areas were more likely than individuals living in rural areas to report progression to other illicit drug use (HR=1.19, 95% CI =1.02-1.36). Compared to cannabis married users, those divorced or separated (HR=1.94, 95% CI =1.49-2.54) and those never married (HR=2.15, 95% CI =1.79-2.58) were more likely to report progression to other illicit drug use.

3.4.2. Psychiatric and substance use-related predictors

In the adjusted models (Table 4) cannabis users with mood disorder(HR=1.33, 95% CI =1.12-1.57), anxiety disorder (HR=1.17, 95% CI =1.01-1.36), personality disorder (HR=1.34, 95% CI =1.17-1.53), nicotine dependence (HR=1.58, 95% CI =1.35-1.86), alcohol use disorder (AUD) (HR=1.53, 95% CI =1.36-1.72), or cannabis use disorder (CUD) (HR=2.33, 95% CI =2.06-2.62) were more likely to progress to other illicit drug use than individuals without these disorders. Family history of SUD (HR=1.28, 95% CI =1.15-1.43) and early use onset of cannabis (HR=0.94, 95% CI =0.92-0.97) also increased the risk of progression from cannabis use to other illicit drug use.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to identify subgroups of the population at increased risk for progression from cannabis use to use of other illicit drugs in a large, nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. The cumulative probability of transition from cannabis use to other illicit drug use was 44.7%. Several sociodemographic and psychiatric variables and indicators of substance use severity predicted progression, including being male, urban residence, being never married, separated or divorced, having a broad range of psychiatric disorders or a family history of SUD, and early onset of cannabis use.

Our results, in line with previous findings (Agrawal et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2006; Fergusson & Horwood, 2000; Lynskey et al., 2003; Van Gundy & Rebellon, 2010) suggest that a large proportion, but not all, of individuals who use cannabis go on to use other illegal drugs. Moreover, in agreement with the predictions of the GH, a minority of the total NESARC sample reported used other illicit drug before cannabis or only used other illicit drug.

Several complementary pathways involving biochemical, social learning and environmental factors may contribute to explain the progression from cannabis use to other illicit drug use. Cannabis users are often more exposed to opportunities to use other illicit drugs because the environment and distribution channels for cannabis and other illegal drugs frequently overlap (Dishion & Owen, 2002; Fergusson & Horwood, 1997; Wagner & Anthony, 2002). Cannabis use also provides the individual with learning experiences (e.g., pleasurable effects) that can encourage experimentation with other illicit drugs (Fergusson, Horwood, Lynskey, & Madden, 2003). Furthermore, the pharmacological effects of cannabis appear to lead to neuroadaptations that render the brain more sensitive to the euphoric effects of other illicit drugs (Ellgren, Spano, & Hurd, 2007; Schenk, 2002). Being intoxicated with one drug may also lower reservations about using other drugs.

An important, novel finding of the current study was the identification of subgroups of the population at risk for progression to other illicit drug use, i.e., individuals for which cannabis use constitute a gateway to other drug use. Mental disorders (both internalizing and externalizing) predicted progression from cannabis use to other illicit drug use. Several mechanisms may contribute to explain this association. First, individuals with mental disorders may use drugs in a maladaptive attempt to relieve their psychiatric symptoms, which may lead to further escalation (Compton, Dawson, Conway, Brodsky, & Grant, 2013; Glassman, 1993). Second, in accord with the sensitization hypothesis, cannabis use may potentiate the effect of other drugs, increasing their abuse liability (Huang, Kandel, Kandel, & Levine, 2013; Klein, 2001; Levine et al., 2011; Schenk, 2002). Similarly, drug interactions resulting in decreased adverse effects and synergism of drug effects may favor the simultaneous use of different substances (Desai, Barber, & Terry, 1999; Leri, Bruneau, & Stewart, 2003) and consumption of more than one drug may lead to faster neuroadaptations (Leri et al., 2003). Alcohol, nicotine or cannabis disorders may also trigger the use of other illegal substances through associated environmental factors such as cues and opportunities under peer influence (Mayet et al., 2012). There are also genetic factors that increase the risk of most substances of abuse (Kendler, Jacobson, Prescott, & Neale, 2003).

In accord with prior findings (Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey, 2001b), males were more likely than women to progress to other illicit drug use, consistent with previous research indicating that, in the general population, the prevalence of SUD is higher among men (Compton, Thomas, Stinson, & Grant, 2007; Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey, 2001a; Hasin, Stinson, Ogburn, & Grant, 2007; Regier et al., 1990). Biological (Nolen-Hoeksema & Hilt, 2006) and cultural factors such as peer behavior and socialization into traditional gender roles (Schulte, Ramo, & Brown, 2009; Swendsen et al., 2009) could explain this difference in rates of progression (Khan et al., 2013). Our study also found that the probability of progression to other illicit drug use was higher for individuals living in urban settings and for those divorced, separated or never married, while it was lower for Blacks compared to Whites. Higher availability of drugs, lower family cohesion or more diffuse social networks may help explain the higher risk of progression to illicit drug use among individuals in urban settings (Martino, Ellickson, & McCaffrey, 2008). Previous research has documented a consistent association between SUD and lower social support (Boden, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2013). Genetic protective factors (Scott & Taylor, 2007) and cultural/environmental (Gibbs et al., 2013; Giger, Appel, Davidhizar, & Davis, 2008; McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Keyes, 2010; Primm et al., 2010) variables such as role modeling and interpersonal influence may decrease the risk for progression to use of other illicit drugs among Blacks compared to Whites (Griesler & Kandel, 1998). Furthermore, consistent with prior work (Agrawal et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2006; Kandel, 1984; Morral et al., 2002), earlier age at first cannabis use, increased the probability of other illegal drug use. Given the strong association between early use of cannabis, cannabis use disorder and progression to other illicit drug use, delaying cannabis use could reduce the probability of use of other illicit drugs among individuals who start cannabis use before using any other illicit drug.

Taken together, these results suggest that the strength associations between cannabis use and other illicit drug use may be driven by individual characteristics rather than being wholly explained by causal mechanisms. This pattern of transition is compatible with a common liability model of vulnerability to addictions (Morral et al., 2002). One potential policy implication is that preventive strategies that target this underlying common liability may be overall more effective than those focused on individual drugs. Nevertheless, because cannabis is the most commonly used drug, policies that contribute to decrease cannabis use may useful in reducing involvement in other illicit drugs use particularly among individuals psychiatric comorbidity.

These results should be considered in the light of some methodological limitations. First, information on substance use and SUD was based on self-report and not confirmed by objective methods which may have led to an underestimate due to the stigma associated with mental health problems (Pickles et al., 1998). Second, diagnoses may be subject to recall bias and to cognitive impairment associated with the use of drugs. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the study limits our ability to draw causal inferences. Therefore, while we are able to describe associations, we are not able to ascribe causality. Fourth, by design, we focused on individuals who started using cannabis before use of any other illicit drug. Our results may not generalize to those whose use of other illicit drugs preceded use of cannabis. The study of determinants of other illicit drugs use among subjects who followed alternative sequences should be made to complete the present study. It also some important strengths, including its large sample size, generalizability (except for individuals just mentioned), careful methodology and the inclusion of predictors that have not been examined in previous studies.

In conclusion, our study indicates that about 40% of individuals with lifetime cannabis use progressed to other illicit drug use, highlighting the potential dangers of policies that may increase the availability of cannabis, at least for the fraction of individuals at risk for other illicit drug use. Furthermore, psychiatric comorbidity is a strong predictor of the association between cannabis use and progression to other illicit drug use. There is a need to consider the health benefits and adverse effects of changes in cannabis regulation that expand access to this substance, and for the development of prevention and intervention efforts targeted at cannabis users with co-occurring mental disorders.

Highlights.

We examined progression from cannabis use to other illicit drugs use in the NESARC.

44.7% of individuals with lifetime cannabis use progressed to other illicit drug use.

Mental disorders predicted progression from cannabis use to other illicit drug use.

This study can help guide interventions for drug use and cannabis regulations.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source The NESARC was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Bethesda, MD, with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda. Work on this manuscript was supported by NIH grants DA019606, DA020783, DA023200, DA023973 and CA133050 (Dr. Blanco), by the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Dr. Blanco) and by the University of Oviedo (Drs. Secades-Villa and García-Rodríguez).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest No conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal A, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. A twin study of early cannabis use and subsequent use and abuse/dependence of other illicit drugs. Psychological medicine. 2004;34(7):1227–1237. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4 ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Alderson D, Ogburn E, Grant BF, Nunes EV, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hasin DS. Changes in the prevalence of non-medical prescription drug use and drug use disorders in the United States: 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;90(2-3):252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.005. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Rafful C, Wall MM, Ridenour TA, Wang S, Kendler KS. Towards a comprehensive developmental model of cannabis use disorders. Addiction. 2014;109(2):284–294. doi: 10.1111/add.12382. doi: 10.1111/add.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Secades-Villa R, Garcia-Rodriguez O, Labrador-Mendez M, Wang S, Schwartz RP. Probability and predictors of remission from life-time prescription drug use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47(1):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.019. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Alcohol misuse and relationship breakdown: Findings from a longitudinal birth cohort. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133(1):115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.023. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M, Ramirez R, Febo VE, Rubio-Stipec M, Fernandez RL, Hasin D. The Spanish Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability and concordance with clinical diagnoses in a Hispanic population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(6):790–799. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Dawson DA, Conway KP, Brodsky M, Grant BF. Transitions in illicit drug use status over 3 years: a prospective analysis of a general population sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(6):660–670. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060737. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12060737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J, Rooke S, Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: impact on mental health. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2013;26(4):325–329. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361eae5. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361eae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Conway K, Dierker L, Glantz M, Kalaydjian A, Kessler RC. Does the ’gateway’ matter? Associations between the order of drug use initiation and the development of drug dependence in the National Comorbidity Study Replication. Psychological medicine. 2009;39(1):157–167. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003425. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Chiu WT, Medina-Mora ME, Neumark Y, Sampson N, Kessler RC. Evaluating the drug use “gateway” theory using cross-national data: consistency and associations of the order of initiation of drug use among participants in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108(1-2):84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.001. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use among Australians: a comparison of their associations with other drug use and use disorders, affective and anxiety disorders, and psychosis. Addiction. 2001a;96(11):1603–1614. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961116037.x. doi: 10.1080/09652140120080732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. The relationship between cannabis use and other substance use in the general population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001b;64(3):319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RI, Barber DJ, Terry P. Asymmetric generalization between the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and cocaine. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1999;10(6-7):647–656. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Owen LD. A longitudinal analysis of friendships and substance use: bidirectional influence from adolescence to adulthood. Developmental psychology. 2002;38(4):480–491. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.4.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgren M, Spano SM, Hurd YL. Adolescent cannabis exposure alters opiate intake and opioid limbic neuronal populations in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(3):607–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301127. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101(4):556–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early onset cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in young adults. Addiction. 1997;92(3):279–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Does cannabis use encourage other forms of illicit drug use? Addiction. 2000;95(4):505–520. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9545053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT, Madden PA. Early reactions to cannabis predict later dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(10):1033–1039. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Salamanca L, Secades-Villa R, Hasin DS, Cottler L, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of transition from abuse to dependence on alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(3):168–179. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.772618. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.772618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs TA, Okuda M, Oquendo MA, Lawson WB, Wang S, Thomas YF, Blanco C. Mental health of African Americans and Caribbean blacks in the United States: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(2):330–338. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger JN, Appel SJ, Davidhizar R, Davis C. Church and spirituality in the lives of the African American community. Journal of transcultural nursing. 2008;19(4):375–383. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322502. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH. Cigarette smoking: implications for psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(4):546–553. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub A, Johnson BD. The shifting importance of alcohol and marijuana as gateway substances among serious drug abusers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(5):607–614. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Kay W, Pickering R. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV (AUDADIS IV): reliability of alcohol consumption, tobacco use, family history of depression and psychiatric diagnostic modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;71(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Huang B, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Compton WM. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14(11):1051–1066. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Prevalence, correlates, and disability of personality disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):948–958. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, June Ruan W, Goldstein RB, Huang B. Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological medicine. 2005;35(12):1747–1759. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Kaplan KD. Source and Accuracy Statement for the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Rockville, Maryland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Pickering RP. Co-occurrence of 12-month alcohol and drug use disorders and personality disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):361–368. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau LE, Dasgupta N, Harvey AP, Irwin K, Givens A, Kinzly ML, Heimer R. Illicit use of opioids: is OxyContin a “gateway drug”? The American Journal of Addictions. 2007;16(3):166–173. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375293. doi: 10.1080/10550490701375293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in correlates of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(3):167–180. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman GA, Ogburn E, Gorroochurn P, Keyes KM, Hasin D. Evidence for a two-stage model of dependence using the NESARC and its implications for genetic association studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1-3):258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemehsow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression Modeling of Time to Event Data. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel DB, Kandel ER, Levine A. Nicotine primes the effect of cocaine on the induction of LTP in the amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins SP. Easy estimation methods for discrete-time duration models. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 1995;57(1):129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Stages in adolescent involvement in drug use. Science. 1975;190(4217):912–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1188374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Marijuana users in young adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41(2):200–209. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790130096013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Does marijuana use cause the use of other drugs? The Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;289(4):482–483. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53(5):447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Klein LC. Testing the Gateway Hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101(4):470–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01426.x. discussion 474-476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Jacobson KC, Prescott CA, Neale MC. Specificity of genetic and environmental risk factors for use and abuse/dependence of cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, sedatives, stimulants, and opiates in male twins. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(4):687–695. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Perez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, Blanco C. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;130(1-3):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC. Effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on opioid consumption and neuroendocrine responses in adult male and female rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2001;9(3):251–261. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri F, Bruneau J, Stewart J. Understanding polydrug use: review of heroin and cocaine co-use. Addiction. 2003;98(1):7–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Huang Y, Drisaldi B, Griffin EA, Jr., Pollak DD, Xu S, Kandel ER. Molecular mechanism for a gateway drug: epigenetic changes initiated by nicotine prime gene expression by cocaine. Science translational medicine. 2011;3(107):107ra109. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Hasin DS, de Los Cobos JP, Pines A, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of remission from life-time nicotine, alcohol, cannabis or cocaine dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2011;106(3):657–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Perez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115(1-2):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Madden PA, Nelson EC, Martin NG. Escalation of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs co-twin controls. The Journal of American Medical Association. 2003;289(4):427–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Fendrich M, Goldstein PJ. Sequence of drug use among serious drug users: typical vs atypical progression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;45(3):185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin D, Cheung YB, Parmar MKB. Survival analysis : a practical approach. 2nd ed Wiley; Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Makanjuola VA, Oladeji BD, Gureje O. The gateway hypothesis of substance abuse: an examination of its applicability in the Nigerian general population. Substance Use & Misuse. 2010;45(10):1558–1571. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682081. doi: 10.3109/10826081003682081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone PS, Lamis DA, Masyn KE, Northrup TF. A Dual-Process Discrete-Time Survival Analysis Model: Application to the Gateway Drug Hypothesis. Multivariate behavioral research. 2010;45(5):790–805. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.519277. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.519277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early to late adolescence: a comparison of rural and urban youth. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2008;69(3):430–440. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, Blanco C, Zhu H, Storr CL. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological medicine. 2012;42(6):1261–1272. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayet A, Legleye S, Falissard B, Chau N. Cannabis use stages as predictors of subsequent initiation with other illicit drugs among French adolescents: use of a multi-state model. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(2):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.012. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Responses to discrimination and psychiatric disorders among Black, Hispanic, female, and lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(8):1477–1484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Burke M, Lewis G. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370(9584):319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morral AR, McCaffrey DF, Paddock SM. Reassessing the marijuana gateway effect. Addiction. 2002;97(12):1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L. Possible contributors to the gender differences in alcohol use and problems. The Journal of general psychology. 2006;133(4):357–374. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.357-374. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.357-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JA, Clayton RR. The stepping-stone hypothesis--marijuana, heroin, and causality. Chemical dependencies. 1982;4(3):229–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Pickering K, Simonoff E, Silberg J, Meyer J, Maes H. Genetic “clocks” and “soft” events: a twin model for pubertal development and other recalled sequences of developmental milestones, transitions, or ages at onset. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28(4):243–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1021615228995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primm AB, Vasquez MJ, Mays RA, Sammons-Posey D, McKnight-Eily LR, Presley-Cantrell LR, Perry GS. The role of public health in addressing racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental illness. Preventing chronic disease. 2010;7(1):A20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebellon CJ, Van Gundy K. Can social psychological delinquency theory explain the link between marijuana and other illicit drug use? A longitudinal analysis of the gateway hypothesis. Journal of drug issues. 2006;36(3):515–539. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, Goodwin FK. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. The Journal of American Medical Association. 1990;264(19):2511–2518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour TA, Maldonado-Molina M, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL, Cottler LB. Factors associated with the transition from abuse to dependence among substance abusers: implications for a measure of addictive liability. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.005. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan WJ, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Smith SM, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Grant BF. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;92(1-3):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DM, Taylor RE. Health-related effects of genetic variations of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in African Americans. Alcohol research & health. 2007;30(1):18–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S. Sensitization as a process underlying the progression of drug use via gateway drugs. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and Pathways of Drug Involvement: Examining the Gateway Hypothesis. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 318–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clinical psychology review. 2009;29(6):535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Patricia Chou S, Smith S, Goldstein RB, June Ruan W, Grant BF. The epidemiology of DSM-IV specific phobia in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological medicine. 2007;37(7):1047–1059. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000086. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, Dierker L, Glantz M, Jin R, Kessler RC. Socio-demographic risk factors for alcohol and drug dependence: the 10-year follow-up of the national comorbidity survey. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1346–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02622.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Ridenour T, Fishbein D, Horner M, Vanyukov M. Does the “gateway” sequence increase prediction of cannabis use disorder development beyond deviant socialization? Implications for prevention practice and policy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123(Suppl 1):S72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.015. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB. Predictors of marijuana use in adolescents before and after licit drug use: examination of the gateway hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(12):2134–2140. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2134. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gastel WA, Tempelaar W, Bun C, Schubart CD, Kahn RS, Plevier C, Boks MP. Cannabis use as an indicator of risk for mental health problems in adolescents: a population-based study at secondary schools. Psychological medicine. 2013;43(9):1849–1856. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002723. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gundy K, Rebellon CJ. A Life-course Perspective on the “Gateway Hypothesis”. Journal of health and social behavior. 2010;51(3):244–259. doi: 10.1177/0022146510378238. doi: 10.1177/0022146510378238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ours JC. Is cannabis a stepping-stone for cocaine? Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22(4):539–554. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ours JC, Williams J. The effects of cannabis use on physical and mental health. Journal of Health Economics. 2012;31(4):564–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, Kirisci L, Reynolds MD, Kreek MJ, Ridenour TA. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;123(Suppl 1):S3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. Into the world of illegal drug use: exposure opportunity and other mechanisms linking the use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155(10):918–925. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: III. Predictors of progression. American Journal of Public Health. 1984;74(7):673–681. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]