Abstract

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated associations of chronic respiratory disease with near-roadway pollutant exposure, effects that were independent of those of regional air pollutants. However, there has been limited study of the potential mechanisms for near-roadway effects. Therefore, we examined the in vitro effect of respirable particulate matter (PM) collected adjacent to a major Los Angeles freeway and at an urban background location. PM was collected on filters during two consecutive 15-day periods. Oxidative stress and inflammatory response (intracellular reactive oxygen species [ROS], IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) to PM aqueous extract was assessed in THP-1 cells, a model for evaluating monocyte/macrophage lineage cell responses. The near-roadway PM induced statistically significantly higher levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (P < 0.01) and a near significant increase in IL-1β (P = 0.06) but did not induce ROS activity (P = 0.17). The contrast between urban background and near-roadway PM-induced inflammatory cytokines was similar in magnitude to that corresponding to temporal differences between the two collection periods. PM-induced proinflammatory protein expression was attenuated by antioxidant pretreatment, and PM stimulation enhanced the activity of protein kinases, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Pretreatment of THP-1 cells with kinase inhibitors reduced PM-induced proinflammatory mediator expression. The proinflammatory response was also reduced by pretreatment with polymyxin B, suggesting a role for endotoxin. However, the patterns of PM-induced protein kinase response and the attenuation of inflammatory responses by antioxidant or polymyxin B pretreatment did not vary between near-roadway and urban background locations. We conclude that near-roadway PM produced greater inflammatory response than urban background PM, a finding consistent with emerging epidemiologic findings, but these differences were not explained by PM endotoxin content or by MAPK pathways. Nevertheless, THP-1 cells may be a model for the development of biologically relevant metrics of long-term spatial variation in exposure for study of chronic disease.

Keywords: traffic-related air pollution, oxidative stress, inflammation, exposure assessment, epidemiology

Clinical Relevance

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated associations of chronic respiratory disease with near-roadway pollutant exposure, effects that were independent of those of regional air pollutants. However, there has been limited study of the potential mechanisms for near-roadway effects. Therefore, we examined the in vitro effect of respirable particulate matter collected on filters during two consecutive 15-day periods adjacent to a major Los Angeles freeway and at an urban background location.

Adverse health effects after exposure to ambient air particulate matter less than 10 μm (PM10) and 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter (PM2.5) include exacerbations of asthma and other respiratory tract diseases and are a crucial public health concern (1). Several recent studies suggest that the near-roadway air pollution mixture within a few hundred meters of a major roadway causes chronic respiratory effects that are independent of background levels of regional ambient PM (2, 3). Potential causal explanations for these observations include more toxic PM components in near-roadway pollution (NRP). However, it is expensive to measure PM composition on a fine spatial scale relevant to large epidemiological studies.

Low-cost in vitro assays of PM-induced biological activity are an alternative to measuring PM composition. In a study of one such assay in the United Kingdom, near-roadway PM in London was shown to have higher oxidative potential using an acellular system (4). PM-induced proinflammatory response in a murine macrophage cell line was associated with near-roadway exposure in The Netherlands (5). However, there have been few such studies, and even fewer have been conducted in North American cities.

Taken together, these observations suggest that near-roadway PM may have increased pro-oxidant activity with subsequent increased biological potency compared with PM from other locations. To test this hypothesis, we collected PM on filters near a major roadway and at an urban background location in Central Los Angeles, California. These samples were processed so that assessment of activity of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and biological potency of equivalent mass amounts of PM from each collection could be compared.

To assess the biological activity of the batches of PM samples, we used a human monocytic cell line (THP-1 cells) as a target cell for this bioassay, focusing on oxidative stress and proinflammatory responses of these cells across a dose range (μg/ml) of PM. THP-1 cells have been well characterized and are a low-cost, high-throughput system relevant to the response of airway monocytes and macrophages (6). Along with epithelial cells, these are the initial cells that encounter inhaled particulates (7, 8). Inhaled PM can activate airway macrophages via interaction with cell surface receptors and induction of well-known signaling pathways, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways (9–11). Various types of PM have been shown to generate ROS (12, 13), potentially mediating inflammatory or cytotoxic outcomes.

To explore further the role that ROS may play in mediating PM-induced inflammatory responses, we assessed the impact of the antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC) on cytokine production and the activity of JNK and ERK kinases, comparing the action of NAC with that of known inhibitors of these pathways. We also examined the role of endotoxin as a mediator of PM-induced inflammatory response by pretreating PM with the endotoxin inhibitor polymyxin B. In this report we describe our observations, demonstrating that PM obtained from near-road locations have increased proinflammatory actions on THP-1 cells. However, these differences were not explained by PM endotoxin content or by PM-induced oxidant stress.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Triton X-100, polyacrylamide, LPS (Escherichia coli 0127:B8), and polyxmyxin B were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). SDS-PAGE supplies, such as molecular mass standards and buffers, were from Bio-Rad (Richmond, CA). 5-(and-6)-Carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCFDA) was purchased from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), U0126, and SP600125 were obtained from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Phospho-specific and pan antibodies against ERK and JNK antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

PM Collection and Extraction

Size-resolved PM was collected with a Harvard Cascade Impactor (14) modified for the Southern California Children’s Health Study to include an additional cut-point of 0.2 and 0.5 μm in addition to standard size cuts at 2.5 and 10 μm, as previously described, and operated at 5 liters per minute (15, 16). The collection substrate was polyurethane foam (PUF), which allows larger PM mass accumulations before particle bounce or overloading occurs (14, 17). A Teflon backup filter was used to collect PM0.2. Filters were prepared to remove endotoxin from the PUF as previously described (15, 16).

Eight samplers were deployed on a patio approximately 30 m from the I-5 freeway in Los Angeles, and 12 samplers were deployed on a building rooftop at the Health Sciences Campus of the University of Southern California approximately 1 km distant. Two sets of consecutive 2-week samples were collected from April 20 to May 4, 2011 (wave A) and from May 5 to May 19, 2011 (wave B). The consecutive collections allowed an assessment of the replicability of the spatial pattern of PM-induced effects. This design also provided a selected comparison of the relative size of spatial and temporal differences within a single season. At the conclusion of sampling, filters were removed and frozen at −10°C until they were shipped on dry ice to the University of North Carolina, where they were stored at −20°C until extraction.

Before PM extraction, the PUF filters were equilibrated in a conditioning room at 22°C and at 33% relative humidity for 24 hours before weighing on a Mettler balance to within 0.002 mg. Particles were extracted from each filter by vortexing in 0.3 ml sterile distilled water for 10 minutes followed by 30-second sonication. The filters were then lifted from the solution and mildly squeezed to expel excess water into the extraction solution. After re-equilibrating the filters for 24 hours in the conditioning room, postextraction weights were measured, and extracted mass was calculated based on the loss in mass during extraction.

The PM10–0.2 extraction solutions were pooled from each sampler before cell challenge.

Cell Culture

The human monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 was purchased from ATCC (Rockville, MD). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% FBS with penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2; 1 × 106 cells in 0.5 ml medium were incubated in round-bottom polystyrene culture tubes with loosened caps for PM stimulation studies.

Cytotoxicity

One hundred thousand THP-1 cells in 0.2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium were incubated with 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml PM at 37°C for 24 hours in a 96-well cell culture plate (CoStar, Corning, NY). The plate was centrifuged at 500 g for 10 minutes. Cytotoxicity was determined by measuring the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the supernatant using a kit purchased from ClonTech (Mountain View, CA). Cells incubated with 1% Triton-X100 served as a positive control.

Cytokine Assays

One million THP-1 cells in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium were incubated with PM at 37°C for 24 hours. The culture tubes were centrifuged at 500 g for 10 minutes. The supernatants were collected for measurement of IL-8 using quantitative sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) or an array of inflammatory mediators including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α using the Meso Scale Discovery ELISA kit (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD). Negative controls included the PBS solution and the extract from a field filter blank. THP-1 cells were challenged with PM from each location and wave of collection at doses of 0, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml of PM. An optimal dose of 50 μg/ml of PM was used for subsequent mechanistic assays.

Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Selection of Peripheral Blood Monocytes

Because the THP-1 cells were not differentiated in culture to adherent macrophages, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers were also challenged with PM to assess the consistency of response in an ex vivo model. PBMCs were isolated from heparinized peripheral blood using Lymphoprep density gradient centrifugation (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway) and subsequent negative selection using the Dynabeads Untouched Human Monocytes Kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Cells were cultured and challenged with 50 μg/ml PM as described for THP-1 cells.

Immunoblotting

THP-1 cells exposed to 50 μg/ml PM for 2 hours were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and then lysed in RIPA buffer (1× PBS, 1% nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors: 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 20 μg/ml aprotinin, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 200 μM sodium orthovanadate, and 20 mM sodium fluoride). The supernatants of cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk, washed briefly, and incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight, followed by incubating with corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoblot images were detected using chemiluminescence reagents and the Fujifilm LAS-3000 imaging system (Fuji Medical Systems, Stamford, CT).

Measurement of Intracellular ROS

The intracellular formation of ROS in THP-1 cells was detected using the fluorescent ROS probe carboxy-H2DCFDA. Carboxy-H2DCFDA is a cell-permeant indicator for ROS that is nonfluorescent until the acetate groups are removed by intracellular esterases and oxidation occurs within the cell. The green fluorescence produced by THP-1 cells is proportional to the amount of ROS produced. Briefly, THP-1 cells were preincubated with 20 μM carboxy-H2DCFDA at 37°C for 1 hour before exposure to PM for 6 hours. Cells were washed once with PBS, suspended in 0.5 ml PBS, and put on ice before determination of green fluorescence intensity. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSORT (Becton-Dickinson, Miami, FL) by using an argon-ion laser (wavelength 488 nm). The FACSORT was calibrated with Calibrite beads (Becton-Dickinson) before each use, and 6,000 events were counted for all sample runs. Relative cell size and density/granularity were quantified by analyzing light-scatter properties using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson), namely forward scatter for cell size and side scatter for density/granularity, and recording the mean fluorescence intensities for each.

Effect of Antioxidant and Kinase Inhibitors on PM-Induced IL-8 Release

THP-1 cells (1 × 106 cells) were pretreated with 10 mM NAC in PBS for 2 hours before further stimulation with 50 μg/ml PM for 24 hours. IL-8 levels in the supernatants were measured as described previously.

THP-1 cells (1 × 106 cells) were pretreated with 20 μM of ERK inhibitor (U0126) or JNK inhibitor (SP600125) for 30 minutes in DMSO before 50 μg/ml PM treatment for 24 hours. IL-8 levels in supernatants were measured as described previously.

Effect of Polymyxin B on PM-Induced IL-8 Release

THP-1 cells (1 × 105 cells) were pretreated with 5 μg/ml polymyxin B sulfate (an endotoxin-binding antibiotic) in PBS for 30 minutes before further stimulation with 50 μg/ml PM for 24 hours. IL-8 levels in supernatants were measured as described above. Cells were treated with polymyxin B in the presence or absence of 10 ng/ml LPS as a control.

Statistical Analysis

We used ANOVA of outcomes elicited in supernatant from each PM-challenged cell culture to evaluate the variability in the cytokine response due to period of collection and location (near-roadway and urban background), adjusted for dose. Because replicate assays at each dose were correlated, we used the median of the replicate assays in all analyses. Because sample sizes were small, nonparametric ANOVA approaches were used to evaluate statistical significance. Trend across the three doses was assessed by ranking as −1, 0, or 1. Interactions to assess differences in mechanistic effects by roadway proximity (e.g., whether the reduction in PM-induced inflammatory cytokine response by pretreatment with NAC was larger for near-roadway location compared with urban background) were assessed on a multiplicative scale. All hypotheses were two sided and assessed at a 5% level of significance. All analyses were conducted using the SAS Version 9.2 statistical package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The pattern of three replicate assays of each outcome response to PM concentrations from 0 μg/ml (the PBS control and the field blank control) to 100 μg/ml is shown in the online supplement for each particle collection wave and location (see Figures E1–E5 in the online supplement). The response of the extract from the field filter blank and the PBS negative controls were generally in agreement, compared with collected PM, indicating that the cleaning procedure for the filters removed all contaminants that are biologically active in this assay. There was, in general, a clear dose–response relationship. The trend of dose (across the median of three replicates at each dose) was statistically significant for each outcome in the ANOVA adjusted for location and wave of PM collection.

LDH release was used as a metric to determine particle-induced cytotoxicity in THP-1 cells after a 24-hour exposure to PM. There were no differences in LDH activity detected between the field blank and PM-treated samples (data not shown).

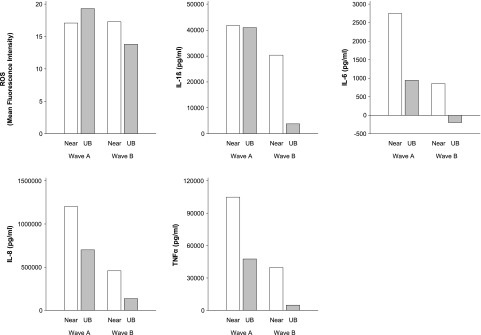

In the ANOVA adjusted for dose and wave of collection, using the data shown in Figures E1 through E5, the NRP produced a larger proinflammatory (IL-6, P = 0.005; IL-8, P = 0.001; and TNF-α, P < 0.0001) response than the urban background PM. The NRP-induced IL-1β response was greater than the response induced by urban background particles, a difference that was marginally significant (P = 0.06). The ROS response to NRP was not different from the response to urban background PM (P = 0.17). For each outcome there was greater response to wave A particles than to wave B particles (adjusted for dose and location), also with the exception of ROS (P = 0.17).

Figure 1 illustrates these patterns of effects of wave of collection and location for each outcome at a PM dose of 50 μg/ml, normalized by subtracting the median of the three replicate PBS control responses from the median response at 50 μg/ml.

Figure 1.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cytokine response to particulate matter (PM) collected at near-roadway (near) and urban background (UB) locations in sampling waves A and B. Data presented are the median of three replicate measurements of response to 50 μg/ml (see Figures E1–E5).

To assess the similarity of the cytokine response in THP-1 to that in human PBMCs, PBMCs from five separate individuals were stimulated with 50 μg/ml PM from each wave and location (Figure E6). The PM-induced IL-8 response in PBMCs showed a pattern that was generally consistent with that observed in the THP-1 assay. There were larger effects of PM from wave A than from wave B (P = 0.005) and from the near-roadway location than from the urban background location (P = 0.01) after adjusting for each other and for subject.

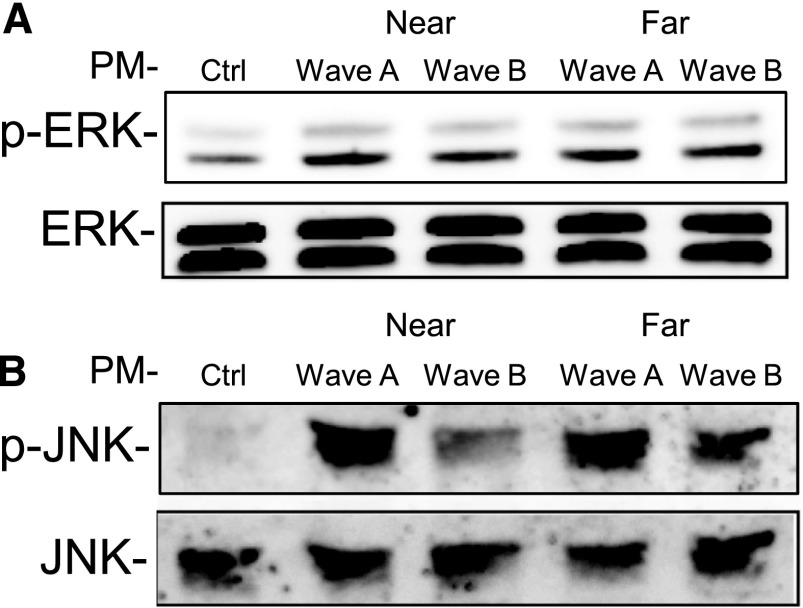

Mechanistic studies were conducted with THP-1 cells at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. The results of the PM-induced kinase activation are shown in Figure 2. Incubation with ambient particles caused a significant increase in detectable phospho-ERK across all treatment groups (Figure 2A). Levels of phospho-JNK were similarly elevated in groups incubated with ambient particles, but the amplitude of this increase in phospho-JNK varied by wave (Figure 2B). Particles collected in wave A induced higher levels of JNK phosphorylation than particles from wave B. However, there were no differences in ERK or JNK phosphorylation between urban and near-roadway locations.

Figure 2.

PM-induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (phospho [p]-ERK) (A, upper panel) and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (phospho [p]-JNK) (B, lower panel) in THP-1 cells during waves A and B at near roadway (near) and urban background (far) sites. Data shown are representative of three separate experiments.

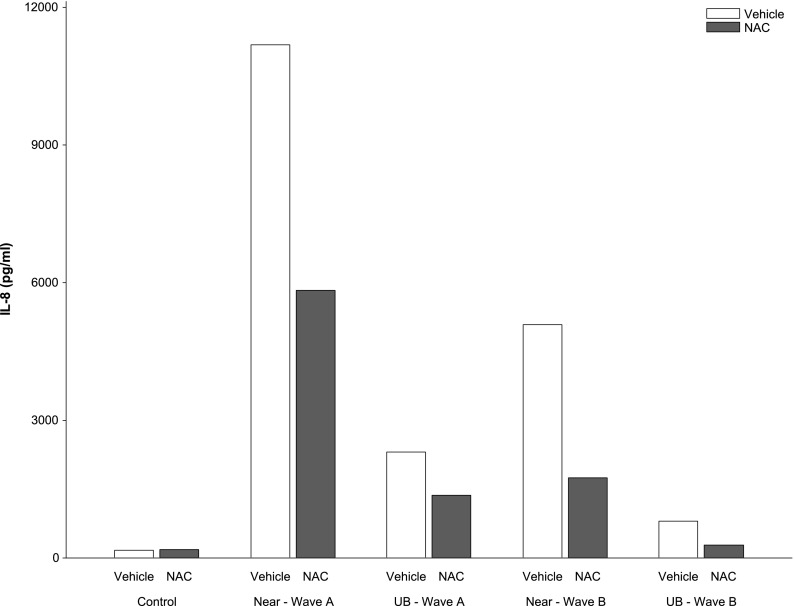

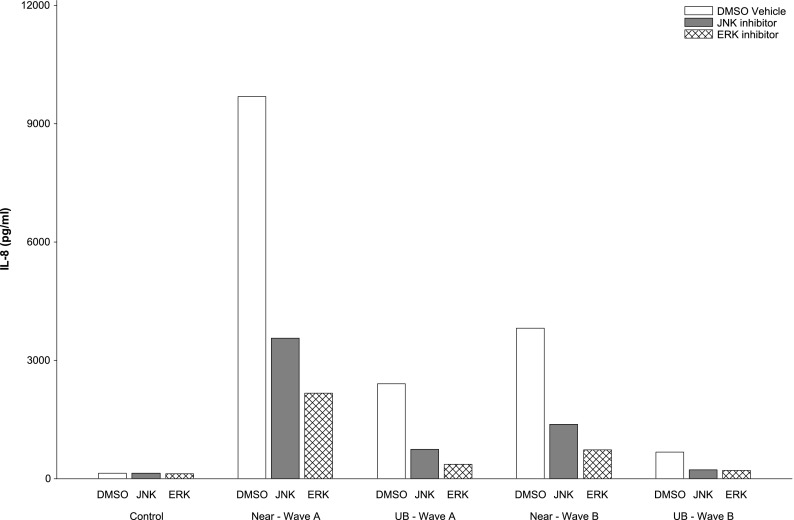

The pattern of three-replicate assays of IL-8 response to PM at 50 μg/ml concentration in PBS vehicle and after pretreatment with NAC, and in DMSO alone and after pretreatment with JNK (SP600125) and ERK inhibitors (U0126), is shown in Figure E7. In general, IL-8 response to PM was dampened in all pretreated groups compared with the response to PM in PBS or DMSO. Pretreatment with NAC reduced the PM-induced response at each location during both waves of sampling compared with PBS vehicle control (P = 0.004, based on the median of each of the three replicates adjusted for wave and location) (Figure 3). Pretreatment with JNK and with ERK inhibitors also resulted in reduced IL-8 response to PM (P = 0.01 and P = 0.002, respectively) (Figure 4). However, these assays provided little evidence that the differences between waves and locations were mediated by oxidative stress because the effect of pretreatment with NAC, JNK, and ERK inhibitors did not vary by location or by wave (interaction P values > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect of n-acetylcysteine (NAC) on PM-induced IL-8 response to near-roadway (near) and urban background (UB) PM in sampling waves A and B. Data presented are the median of three replicate measurements of response to 50 μg/ml (see Figure E7).

Figure 4.

Effect of JNK (SP600125) and ERK (U0126) inhibitors on PM-induced IL-8 response to near-roadway (near) and UB PM in sampling waves A and B. Data presented are the median of three replicate measurements of response to 50 μg/ml (see Figure E7).

The effects of polymyxin B on 50 μg/ml PM-induced IL-8 release are shown in Figure E8 in repeated experiments on four separate days. Cells treated with polymyxin B in addition to PM had reduced median IL-8 release (P = 0.003) in models adjusted for day, wave, and location. The reduction in IL-8 response by polymyxin B was greater in wave A than in wave B, an effect that was of marginal statistical significance (interaction P = 0.054). The effects of polymyxin B on PM-induced release did not differ by location near roadway compared with urban background (interaction P = 0.93).

Discussion

These results demonstrate clear PM-induced innate immune cytokine responses in a cell system relevant for effects on airway macrophages (18, 19). PM from a near-roadway location was substantially more toxic than PM from a nearby urban background location in central Los Angeles. This spatial variation in PM potency was comparable in magnitude to the large temporal variation across the two exposure periods. The generally similar pattern of effects of PM-induced IL-8 response in PBMCs from healthy volunteers suggests that the THP-1 cell PM response has promise as an indicator of in vitro exposure for prediction of in vivo responses.

Particles collected in wave A induced higher levels of JNK phosphorylation than particles from wave B, which is consistent with the general pattern of inflammatory cytokine release in Figure 1 (and with ROS response at the urban background location but not at the near-roadway location). The ROS response to PM and the reduced cytokine response after preincubation of the cells with antioxidant NAC are consistent with the known role of oxidative stress in signaling MAPK pathways and in the inflammatory response to PM implicated in pulmonary cell injury and tissue damage (11, 20, 21). However, the study provided only limited evidence that oxidative stress explained the temporal differences in PM-induced inflammatory cytokine responses (based on the pattern of JNK phosphorylation), given that there was no difference between waves in the impact of pretreatment with NAC and with JNK and ERK inhibitors and no evidence that oxidative stress explained the difference between near-roadway and urban background PM-induced response.

We also demonstrated a role for endotoxin in PM-induced inflammation based on the inhibitory effect of polymyxin B. Studies by our group have demonstrated that airway phagocyte cytokine production in human volunteers exposed to coarse PM preparations were prevented with heating of these particles to eliminate biological components (22). The pattern of polymyxin B effects suggested that endotoxin content of PM may have explained some of the difference in PM-induced inflammatory response between the first 2 weeks of sampling (wave A) and wave B (although this difference between waves did not achieve statistical significance). Endotoxin also did not explain the difference between PM proinflammatory effects at near-roadway and urban background locations. The temporal, but not spatial, differences in endotoxin-driven inflammation correspond with and possibly explain the pattern of phospho-JNK because the THP-1 cell response to LPS has been shown to be mediated by JNK activation (23). Overall, the results suggest that inflammatory pathways may be involved in the epidemiological associations between near-roadway exposure and human respiratory disease, but the specific mechanistic pathways remain to be elucidated.

Although there has been little prior detailed mechanistic study of near-roadway particles, these results differ from European studies that found near-roadway PM–induced oxidative potential to be higher than urban background (4, 5) and that oxidative stress response to near-roadway PM was correlated with inflammatory cytokine release in a mouse macrophage cell line (24). Unlike the European studies, ours was specifically designed to compare the effect of urban background PM with that of a very strong NRP source in the same neighborhood with over 234,000 vehicles daily, approximately 6.3% of which were diesel fueled. Alternatively, it is possible that the carboxy-H2DCFDA probe is not as sensitive as the measured inflammatory markers to the PM components responsible for the inflammatory response because different tests of oxidant potential respond more strongly to the same PM component (5). The lack of an association of ROS assay results with PM source also may reflect random variation in a small sample size. However, the failure of the mechanistic studies to reflect differences between near-roadway and background effects make these less likely explanations. It is also likely that there are other pathways in addition to oxidative stress that contribute to the pattern of inflammatory effects of near-roadway and urban background PM.

Differences in composition of PM account for spatial and seasonal differences in toxicity between particles (13, 25–30) and perhaps for differences between size fractions (13, 24, 25). However, it would be prohibitively expensive to measure all the toxicologically relevant species in organic carbon and elemental carbon, metals, and other contributors to the aerosol, to name a few PM components, on the fine spatial and temporal scale necessary to evaluate chronic effects of NRP in epidemiological studies of populations living throughout large geographic regions.

Our study design provides a model for further research to identify likely components and mechanisms for NRP effects. In addition, the substantial difference between biological activity of near-roadway and urban background PM collected on filters in an efficient system like the THP-1 cell line suggests that variability in PM biological activity could be used as a low-cost alternative to measurement of particle composition. This would be a useful new approach for exposure assessment in epidemiological studies of PM impact on human disease. Previous studies using material from the Utah Valley support the use of in vitro PM-induced response as a proxy for in vivo effects by demonstrating that in vitro response predicted in vivo lung inflammatory response in animal and human experimental studies and in population epidemiological studies (31–34).

Recent European studies have examined the potential for modeling the spatial variation in biological activity of PM. Fine-scale spatial variation in in vitro oxidative potential of PM in London has been used to model PM-induced biological activity (4), just as the spatial variation of surrogates for near-roadway exposure, such as NO2 or black carbon, are modeled using traffic proximity and other land use information (35). Near-roadway PM in London was shown to have higher oxidative potential as assessed in an acellular system but has not yet been used to evaluate associations with disease. A consensus is emerging that in vitro cell challenges using models like the THP-1 cell line we have used have advantages over in vitro acellular systems for assessing the toxicity of PM (36). Broad spatial variability in PM proinflammatory cellular response was shown to be related to near-roadway exposure in one study in The Netherlands (5, 24).

There are potential limitations to using PM-induced biological activity for exposure assessment in chronic disease epidemiology, which typically require temporally synchronized deployment at multiple locations during several 2-week or longer periods throughout the year (37, 38). For example, we have previously shown that biological activity varies with duration of collection of sample (15). Another recent study demonstrated that PM-induced biological activity varied depending on the collection method (39). Water extracts of PM collected on filters or impactors had lower oxidant activity than PM collected directly into a slurry. The investigators concluded that the difference was due to the loss of activity of water-insoluble particles from the extract of filters and impactors. However, a bias in PM-induced biological activity measured in filter-based samples or due to longer duration of sampling required to obtain long-term estimates of exposure may not be a major limitation. As long as the measured biological activity is correlated with the true activity of inhaled ambient PM, the measured activity may provide a valid index of effect in a biologically relevant pathway. Further investigation is required to assess the utility of these methods for epidemiological studies.

We did not extract the 0.2 μm in aerodynamic diameter size fraction, which included the ultrafine fraction (< 0.1 μm) that other studies have found was greater than in the rest of PM10 (40–42). However, the water extraction efficiency of ultrafine particles from filters is less than that for larger particles and decreases by size within the ultrafine fraction due to Van der Wall forces, which can overcome the force available to remove the particle (43). For this reason, we did not include the PM0.2 fraction in our assay of biological activity because there are not good methods for extraction from Teflon filters without changing the biological activity of the extract.

In conclusion, inflammatory cytokine activity after near-roadway PM challenge of a cellular model for airway macrophage response was substantially larger than the activity associated with urban background PM. Our results provide biologically plausible evidence supporting the epidemiological studies suggesting that near-road PM has increased impacts on human health. THP-1 cells are a potential model for the development of biologically relevant metrics of long-term spatial variation in exposure for study the of chronic disease. However, the PM components of NRP and the mechanism underlying its in vitro effects merit further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gaurav Verma for collecting samples and providing logistical support for field work, and James Samet for providing valuable advice on procedures for filter extraction.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P30ES007048, P01ES011627, P01ES022845, R01 ES016535, T32 ES007126, K25ES019224, and U19AI077437; by Environmental Protection Agency grants CR 83346301, RD83544101, and R831845; and by the Hastings Foundation.

Author Contributions: W.W. and R. Muller contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing and editing of the manuscript. K.B. and F.L. performed statistical analyses. S.F. provided technical expertise for sample collection. I.J. and D.D.-S. contributed to study design and analysis and interpretation of data. D.B.P. and R. McConnell contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, and editing of the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0265OC on June 4, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.US Environmental Protection Agency. Research Triangle Park, NC: Office of Air and Radiation, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, Health and Environmental Impacts Division; 2010. Quantitative health risk assessment for particulate matter. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Effects Institute. Boston, MA: Health Effects Institute; 2009. Traffic-related air pollution: a critical review of the literature on emissions, exposure, and health effects (special report 17) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson H, Favarato G, Atkinson R. Long-term exposure to air pollution and the incidence of asthma: meta-analysis of cohort studies. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 2013;6:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanosky JD, Tonne CC, Beevers SD, Wilkinson P, Kelly FJ. Modeling exposures to the oxidative potential of PM10. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:7612–7620. doi: 10.1021/es3010305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boogaard H, Janssen NA, Fischer PH, Kos GP, Weijers EP, Cassee FR, van der Zee SC, de Hartog JJ, Brunekreef B, Hoek G. Contrasts in oxidative potential and other particulate matter characteristics collected near major streets and background locations. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120:185–191. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) Int J Cancer. 1980;26:171–176. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danielsen PH, Møller P, Jensen KA, Sharma AK, Wallin H, Bossi R, Autrup H, Mølhave L, Ravanat JL, Briedé JJ, et al. Oxidative stress, DNA damage, and inflammation induced by ambient air and wood smoke particulate matter in human A549 and THP-1 cell lines. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:168–184. doi: 10.1021/tx100407m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laval-Gilly P, Falla J, Klestadt D, Henryon M. A new approach to evaluate toxicity of gases on mobile cells in culture. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2000;44:483–488. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(01)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marais R, Marshall CJ. Control of the ERK MAP kinase cascade by Ras and Raf. Cancer Surv. 1996;27:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Prophete C, Soukup JM, Chen LC, Costa M, Ghio A, Qu Q, Cohen MD, Chen H. Roles of MAPK pathway activation during cytokine induction in BEAS-2B cells exposed to fine World Trade Center (WTC) dust. J Immunotoxicol. 2010;7:298–307. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2010.509289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samet JM, Graves LM, Quay J, Dailey LA, Devlin RB, Ghio AJ, Wu W, Bromberg PA, Reed W. Activation of MAPKs in human bronchial epithelial cells exposed to metals. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L551–L558. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.3.L551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker S, Dailey LA, Soukup JM, Grambow SC, Devlin RB, Huang YC. Seasonal variations in air pollution particle-induced inflammatory mediator release and oxidative stress. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:1032–1038. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts ES, Richards JH, Jaskot R, Dreher KL. Oxidative stress mediates air pollution particle-induced acute lung injury and molecular pathology. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:1327–1346. doi: 10.1080/08958370390241795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SJ, Demokritou P, Koutrakis P, Delgado-Saborit JM. Development and evaluation of personal respirable particulate sampler (prps) Atmos Environ. 2006;40:212–224. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McConnell R, Wu W, Berhane K, Liu F, Verma G, Peden D, Diaz-Sanchez D, Fruin S. Inflammatory cytokine response to ambient particles varies due to field collection procedures. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:497–502. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0320OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fruin S, Urman R, Lurmann F, McConnell R, Gauderman J, Rappaport E, Franklin M, Gilliland FD, Shafer M, Gorski P, et al. Spatial variation in particulate matter components over a large urban area. Atmos Environ (1994) 2014;83:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.10.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kavouras IG, Koutrakis P. Use of polyurethane foam as the impaction substrate/collection medium in conventional inertial impactors. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2001;34:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rysz J, Banach M, Cialkowska-Rysz A, Stolarek R, Barylski M, Drozdz J, Okonski P. Blood serum levels of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-alpha and IL-1beta in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Z. The use of thp-1 cells as a model for mimicking the function and regulation of monocytes and macrophages in the vasculature. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plummer L, Smiley-Jewell S, Pinkerton K. Impact of air pollution on lung inflammation and the role of toll-like receptors. Int J Interferon Cytokine Mediator Res. 2012;4:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nel A. Atmosphere: air pollution-related illness: effects of particles. Science. 2005;308:804–806. doi: 10.1126/science.1108752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alexis NE, Lay JC, Zeman K, Bennett WE, Peden DB, Soukup JM, Devlin RB, Becker S. Biological material on inhaled coarse fraction particulate matter activates airway phagocytes in vivo in healthy volunteers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1396–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hambleton J, Weinstein SL, Lem L, DeFranco AL. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in bacterial lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2774–2778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steenhof M, Gosens I, Strak M, Godri KJ, Hoek G, Cassee FR, Mudway IS, Kelly FJ, Harrison RM, Lebret E, et al. In vitro toxicity of particulate matter (PM) collected at different sites in The Netherlands is associated with PM composition, size fraction and oxidative potential: the RAPTES project. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seagrave J, McDonald JD, Bedrick E, Edgerton ES, Gigliotti AP, Jansen JJ, Ke L, Naeher LP, Seilkop SK, Zheng M, et al. Lung toxicity of ambient particulate matter from southeastern U.S. sites with different contributing sources: relationships between composition and effects. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:1387–1393. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell ML, Dominici F, Ebisu K, Zeger SL, Samet JM. Spatial and temporal variation in PM(2.5) chemical composition in the United States for health effects studies. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:989–995. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laden F, Neas LM, Dockery DW, Schwartz J. Association of fine particulate matter from different sources with daily mortality in six U.S. cities. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:941–947. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Franklin M, Koutrakis P, Schwartz P. The role of particle composition on the association between PM2.5 and mortality. Epidemiology. 2008;19:680–689. doi: 10.1097/ede.0b013e3181812bb7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostro B, Tobias A, Querol X, Alastuey A, Amato F, Pey J, Pérez N, Sunyer J. The effects of particulate matter sources on daily mortality: a case-crossover study of Barcelona, Spain. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:1781–1787. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell ML, Ebisu K, Peng RD, Samet JM, Dominici F. Hospital admissions and chemical composition of fine particle air pollution. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:1115–1120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1240OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dye JA, Lehmann JR, McGee JK, Winsett DW, Ledbetter AD, Everitt JI, Ghio AJ, Costa DL. Acute pulmonary toxicity of particulate matter filter extracts in rats: coherence with epidemiologic studies in Utah Valley residents. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:395–403. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghio AJ, Devlin RB. Inflammatory lung injury after bronchial instillation of air pollution particles. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:704–708. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2011089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frampton MW, Ghio AJ, Samet JM, Carson JL, Carter JD, Devlin RB. Effects of aqueous extracts of PM(10) filters from the Utah valley on human airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:L960–L967. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.277.5.L960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pope CA., III Respiratory hospital admissions associated with PM10 pollution in Utah, Salt Lake, and Cache Valleys. Arch Environ Health. 1991;46:90–97. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1991.9937434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoek G, Beelen R, de Hoogh K, Vienneau D, Gulliver J, Fischer P, Briggs D. A review of land-use regression models to assess spatial variation of outdoor air pollution. Atmos Environ. 2008;42:7561–7578. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayres JG, Borm P, Cassee FR, Castranova V, Donaldson K, Ghio A, Harrison RM, Hider R, Kelly F, Kooter IM, et al. Evaluating the toxicity of airborne particulate matter and nanoparticles by measuring oxidative stress potential: a workshop report and consensus statement. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20:75–99. doi: 10.1080/08958370701665517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Franklin M, Vora H, Avol E, McConnell R, Lurmann F, Liu F, Penfold B, Berhane K, Gilliland F, Gauderman W. Predictors of intra-community variation in air quality. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2012;22:135–147. doi: 10.1038/jes.2011.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu X, Brook JR, Guo Y. A statistical assessment of saturation and mobile sampling strategies to estimate long-term average concentrations across urban areas. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2007;57:1396–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daher N, Ning Z, Cho AK, Shafer M, Schauer JJ, Sioutas C. Comparison of the chemical and oxidative characteristics of particulate matter (pm) collected by different methods: filters, impactors, and biosamplers. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2011;45:1294–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Araujo JA, Barajas B, Kleinman M, Wang X, Bennett BJ, Gong KW, Navab M, Harkema J, Sioutas C, Lusis AJ, et al. Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2008;102:589–596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li N, Sioutas C, Cho A, Schmitz D, Misra C, Sempf J, Wang M, Oberley T, Froines J, Nel A. Ultrafine particulate pollutants induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:455–460. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho AK, Sioutas C, Miguel AH, Kumagai Y, Schmitz DA, Singh M, Eiguren-Fernandez A, Froines JR. Redox activity of airborne particulate matter at different sites in the Los Angeles Basin. Environ Res. 2005;99:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hinds WC. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1982. Aerosol technology: properties, behavior, and measurement of airborne particles. [Google Scholar]