Summary (Clinical Implications)

Food allergy-associated elimination diets may place children at risk for impaired growth compared to their peers, especially with elimination of > 2 foods and/or milk.

Keywords: Food allergy, growth

To the Editor

Growth impairment and nutritional deficiencies, including rickets, iron deficiency, and kwashiorkor have been reported in children with elimination diets based on real or perceived follow allergy (RPFA).1–5 These cases demonstrate that the allergen avoidance diets required in FA management place children at risk for growth and nutritional problems. However, few studies have systematically investigated this concern.

One of the only previously published studies in the U.S. was a cross-sectional study comparing 98 children with FA to healthy controls. It reported that children with two or more FAs were shorter, based on height-for-age percentiles, than those with one FA, and that with nutritional counseling and supplementation, daily nutritional requirements could be met.6 The investigators concluded that children with multiple FAs, especially including milk, would benefit from nutritional assessment and continued dietary counseling.

We sought to further investigate the degree to which RPFA is associated with impaired growth, compare the impairment to other chronic childhood illnesses, and to identify specific foods that, when avoided, may place children at greater risk for inadequate growth. We conducted a retrospective chart review of children 1 month - 11 years of age presenting to the UNC Pediatric Clinics during a 5-year period (2007–2011). For each child, we chose only the most recent clinic visit. Subjects were identified by querying ICD-9 billing codes in the clinical research database CDW-H (Carolina Database Warehouse for Health), an IRB-approved repository of information generated during clinical visits; subjects were diagnosed in the Pediatric Allergy/Immunology Clinic using ICD-9 codes 995.6, V15.01, V15.02, V15.03, V15.04, V15.05, or 963.1. The number and type of RPFAs were confirmed by manual chart review of provider assessments and laboratory data by the same allergist (C.B.H). Reflective of real-world practice, patients did not routinely undergo oral food challenges for diagnosis, but were eliminating foods based on clinical suspicion of allergy. Healthy and diseased controls were identified as patients that fell into the same age range as RPFA subjects, who presented to the UNC Pediatric Clinics during the same time period for well child care, or for celiac disease (CD) or cystic fibrosis (CF), respectively. We chose these conditions because of their prevalence in our clinic population and their known negative impact on growth. Subjects with documentation of another chronic disease that could affect growth were excluded. There were no exclusions based on race, gender, or ethnicity.

We used a Wald test to compare mean average height-for-age, weight-for-age, and BMI percentiles (WFL for those <2 years), as defined by the CDC clinical growth charts, of RPFA patients to those of healthy and diseased control groups. Subjects under age 2 and those 2 and older were separated when sample size permitted. We report standard errors of the mean throughout the paper. We investigated multivariate analyses, but these results were consistent with the bivariate analyses, so have chosen to present only the latter.

245 children with RPFA were included in the study (mean age 4.1±2.9 years). Within this cohort, the number of RPFA per child ranged from 1 to 7, with an average of 1.9±1.3. The majority (53.8%) had 1 RPFA, 24.9% had 2, and 21.2% had >2. Peanut allergy was the most common RPFA (55.9%), followed by egg (41.6%) and milk (26.9%). Control subjects included 4584 healthy controls and 208 diseased controls (CF, 106; CD, 102). Mean age for healthy control subjects was lower than other groups (3.3±3.6 years), likely due to the number of well-child visits in the first year of life (Table E1). Most subjects with RPFA were Caucasian (48.6%) and male (57.5%). 35% had asthma, 45% had allergic rhinitis, and 33.5% had eczema. 36.7% were < 2 years old; 63% were > 2 years

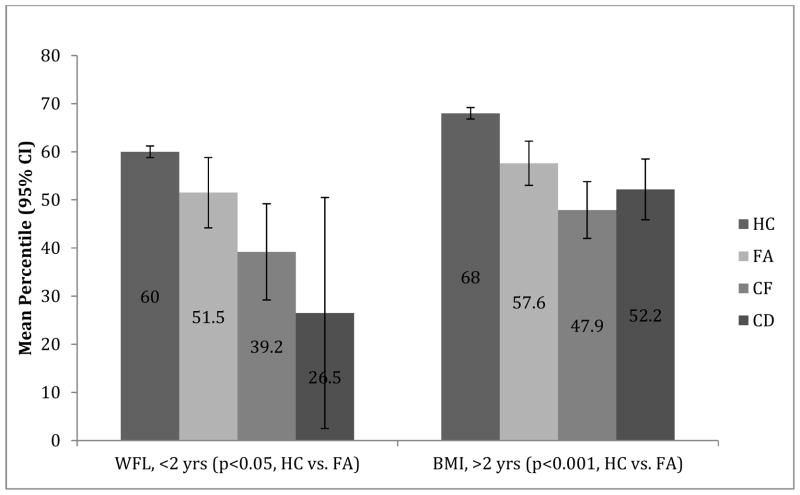

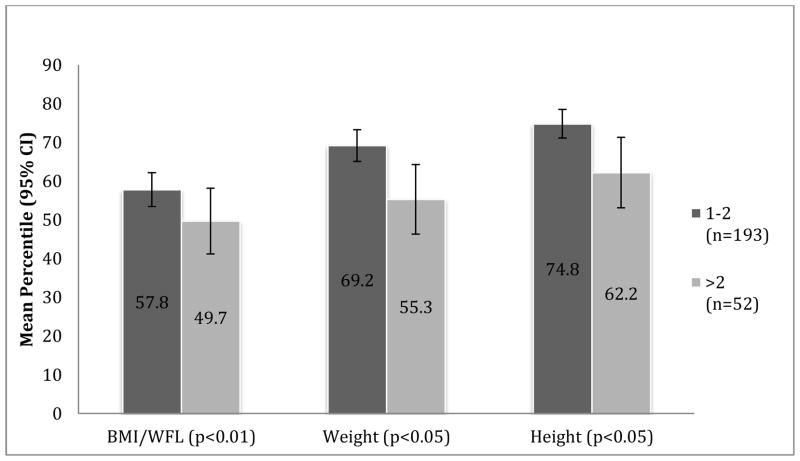

Children under age 2 with RPFA had significantly lower WFL percentiles, and those 2 and older had significantly lower BMI percentiles, compared to healthy controls (Figure 1). The adverse impact of RPFA on WFL was less than that of CD or CF. After age 2, the BMI of children with RPFA was similar to that of children with CD (p=0.18). Mean height percentile of children with RPFA was greater than healthy controls before age 2 (79.7±23.5 vs. 55.2±31.3, p<0.001), but not in older children (69.6±29.2 vs. 69.3±28.1, p=0.89). Growth percentiles did not differ between children with one RPFA vs. two. Compared to those with one or two (n=193), children with more than two RFPAs (n=52) had significantly lower mean weight (55.3±33.1 vs. 69.2±29.1, p<0.001) and height (62.2±33.1 vs. 74.8±26.2, p<0.05) percentiles, respectively (Figure 2). This was the only subset of children for which height was significantly affected by RPFA.

Figure 1.

WFL/BMI Percentiles by Age Group. This figure compares mean WFL/BMI percentiles of 4 groups of children: healthy controls (HC), food allergic (FA), cystic fibrosis (CF), and celiac disease (CD). ). P-values represent Wald statistics of difference between the healthy and food allergy groups; error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Growth Percentiles per Number of Food Allergies. Within the food-allergic cohort, 192 subjects were found to have 1–2 food allergies and 52 were found to have >2 food allergies. Those with >2 allergies had significantly lower mean weight percentile (55.3 [95% CI: 46.3–64.4] vs. 69.2 [95% CI: 65.1–73.3], p<0.01) and height percentile (62.2 [95% CI:53.1–71.2] vs. 74.8 [71.1–78.5], p<0.05) percentiles, respectively.

Children avoiding milk due to RPFA (n=66) had significantly lower mean percentiles for weight (54.5±3.1.2 vs. 70.6±29.1, p<0.001) and WFL/BMI (48.9±31.2 vs. 58.8±31.1, p<0.05) than children avoiding other foods (n=179). The impact of milk avoidance was more pronounced in those younger than 2 years of age (n=31), with mean weight and WFL percentiles markedly lower than those with RPFA to other foods (WFL 38.6±29.5 vs. 56.3±28.4, p<0.05; weight 45.9±32.2 vs. 72.2±29.4, p<0.001). We suspect that this observation is due to the fact that milk and soy-based formulas and foods are a primary source of nutrition in children <2 years.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of the growth parameters of patients followed in a food allergy clinic, and the first to include a control group with diseases known to affect growth. Comparing weight, height, and WFL/BMI percentiles for subjects and controls over a 5-year period demonstrated that children with RPFA have significantly lower weight and WFL/BMI than healthy controls. We hypothesize that this difference is a direct result of food elimination. For all ages evaluated, the impact of RPFA on growth is less significant than that of CF. After age 2, growth parameters of children with RPFA are not different than those of CD. Furthermore, we found the presence of multiple RPFAs and specific avoidance of cow’s milk to be important risk factors for impaired growth. Our findings underscore the imperative for diagnostic accuracy, including oral challenges where necessary, in the evaluation of all children with RPFA, especially so among those who are young and avoiding milk.

Larger prospective studies are needed to further delineate the impact of food allergy on growth, and to investigate the optimal approach for nutritional therapy and/or dietary supplementation. Milk-allergic children less than two years of age may particularly benefit from dietary guidance, as milk and milk-based formulas are a primary source of nutrition in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and funding sources: Support provided by UNC CTSA RR025747. Dr. Skinner is currently supported by BIRCWH (K12-HD01441). Dr. Vickery is supported by NIH-NIAID 5 K23 AI099083-04.

Analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX). This study was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board (IRB#12-1581, reference ID 110959).

Abbreviations

- WFL

Weight for length

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- UNC

University of North Carolina

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Noimark L, Cox HE. Nutritional problems related to food allergy in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008 Mar;19(2):188–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roesler TA, Barry PC, Bock SA. Factitious food allergy and failure to thrive. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994 Nov;148(11):1150–1155. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170110036006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2007 Sep;120(3):638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvares M, Kao L, Mittal V, Wuu A, Clark A, Bird JA. Misdiagnosed Food Allergy Resulting in Severe Malnutrition in an Infant. Pediatrics. 2013 Jun 3; doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu T, Howard RM, Mancini AJ, et al. Kwashiorkor in the United States: fad diets, perceived and true milk allergy, and nutritional ignorance. Archives of dermatology. 2001 May;137(5):630–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christie L, Hine RJ, Parker JG, Burks W. Food allergies in children affect nutrient intake and growth. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002 Nov;102(11):1648–1651. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.