Abstract

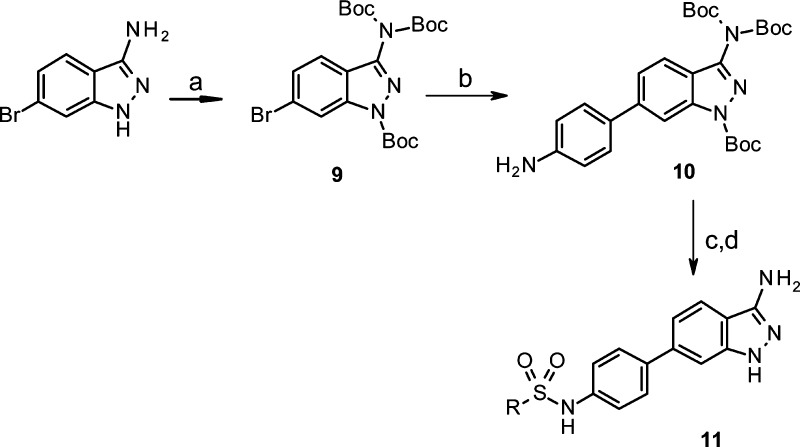

From a virtual screening starting point, inhibitors of the serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 were developed through a combination of classical medicinal chemistry and library approaches. This resulted in highly active small molecules with nanomolar activity and a good overall in vitro and ADME profile. Furthermore, the compounds exhibited unusually high kinase and off-target selectivity due to their rigid structure.

Keywords: Serum glucocorticoid regulated kinase, WNT signaling, AGC kinase, virtual screening

The serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) belongs to the serine/threonine kinase family (AGC kinases) and is an important downstream effector in the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase pathway. SGK1 regulates transport, hormone release, cell proliferation, and apoptosis.1,2 There is a strong body of evidence that dysfunction or dysregulation of SGK1 is involved in many pathological conditions ranging from cancer, hypertension, diabetes, and thrombotic events to neurodegeneration.3−6 Albeit ubiquitously expressed, the transcription is highly regulated and stimulated by physiological events like hyperglycaemia, cell shrinkage, ischemia, glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids, and insulin as well as by inflammatory mediators including TGFβ. SGK1 regulates several ion channels such as ENaC, KCNE1/KCNQ1, carriers like NCC, NHE3, SGLT1, Na(+)/K(+)-ATPase, and transcription factors including FOXO3a, NF-κβ, and β-catenin.7−11 Recently, it was shown that β-catenin phosphorylation by SGK1 mediates the crosstalk between the corticoid- and WNT-signaling pathways.7,12,13 Surprisingly, despite the highly relevant, validated biological function of SGK1 only a few inhibitors with appropriate selectivity and potency for the selective interference with SGK1 have been described so far.14−17 Here we report the identification and optimization of highly active and selective SGK1 inhibitors as chemical tools for the further elucidation and validation of the biological role of SGK1.18

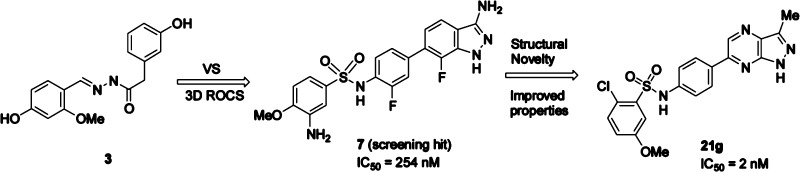

Computational screening, particularly 3D ligand-based virtual screening technologies, have emerged as efficient methods for the discovery of novel drug candidates.19−21 Ligand-based virtual screening uses known active molecules to identify new ligands sharing a set of relevant molecular properties such as molecular shape and electrostatics. A limited number of inhibitors of SGK1 have been described in the literature so far including the azaindoles 1 and 2, the hydrazides 3 and 4, and their 3-aminoindazole isosteres 5 and 6 as shown in Figure 1.22

Figure 1.

SGK1 inhibitors published by GSK14 and Merck15 were used as template structures for ligand-based virtual screening.

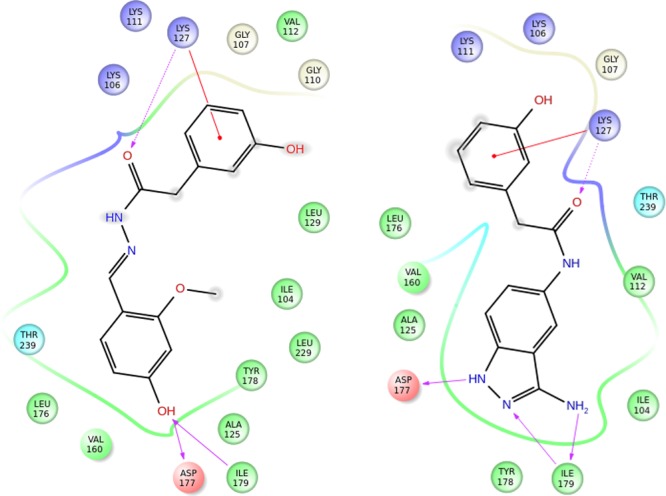

Cocrystal structures of ligands 1 and 2 in the SGK1 enzyme supported a bidentate interaction of the ligand scaffold with the kinase hinge region.14 Using a docking model23 a bidentate hinge interaction of the para-phenolic substituent was also assumed for 3 and 4 as well as a tridentate interaction for compounds 5 and 6 (Figure 2).We applied a conformational analysis of the four reference ligands 3–6 using the Omega software24 to select suitable minimum-energy conformations.25 These conformations were screened accordingly against a corporate database of approximately two million available chemical structures prepared in suitable multiconformer format. For 3D shape-based virtual screening we used the computer program Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures (ROCS)24 with default parameter settings, as this tool is particularly suited for large-scale 3D database searches.26 This method identifies potential novel ligands by maximizing the superposition of Gaussian-type heavy atom functions of the query ligands to those of the reference ligands.

Figure 2.

Ligand interaction diagrams for 3 and 5 to activated SGK1. Similar interactions to the hinge region (right, green) are proposed by a docking model, suggesting the formation of a bidentate hinge interaction for the phenol and a putatively stable tridentate motif for the 3-aminoindazole scaffold, respectively.

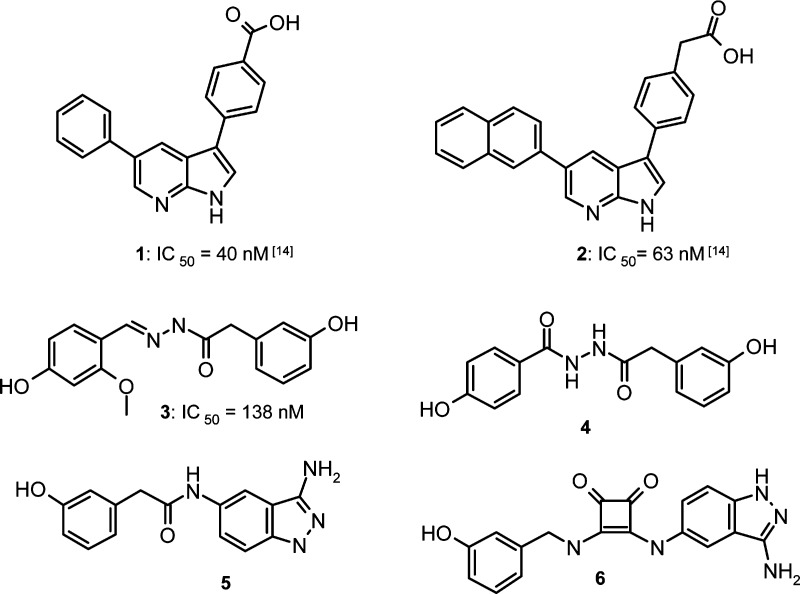

ROCS further accounts for equivalent polar atoms using a predefined parameter set of so-called “colors” that are mapped to the heavy atoms according to their atom types. A resulting hit list was ranked according to the combined shape overlay and color match score (combo score). Hits were selected based on a minimum combo score of 1.2 in the search algorithm, and 78 hits with a heterocyclic scaffold were chosen for experimental validation and tested for SGK1 inhibitory activity in a substrate phosphorylation lab-chip caliper assay.27 Seven compounds were confirmed experimentally and a novel class of 6-sulfamido-phenyl-3-aminoindazoles were identified as moderately potent SGK1 inhibitors. Compounds 7 and 8 were found to have a SGK1 inhibitory activity of IC50 = 254 and 182 nM at 10 μM ATP concentration, respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

SGK1 inhibitors 7 and 8.

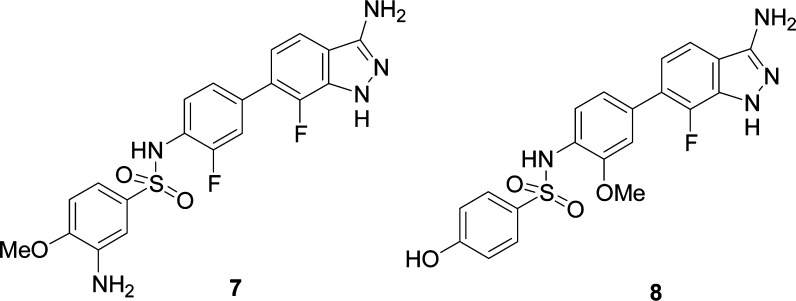

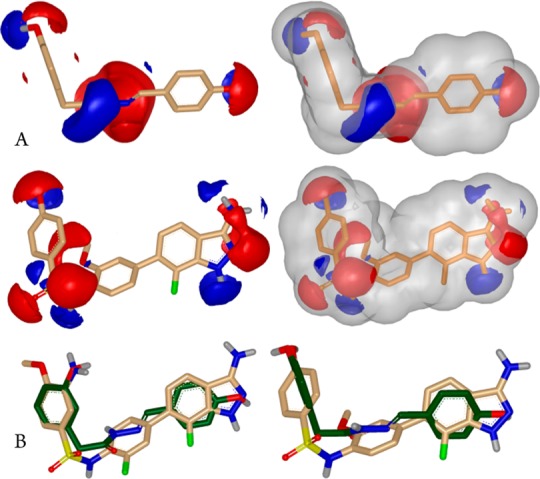

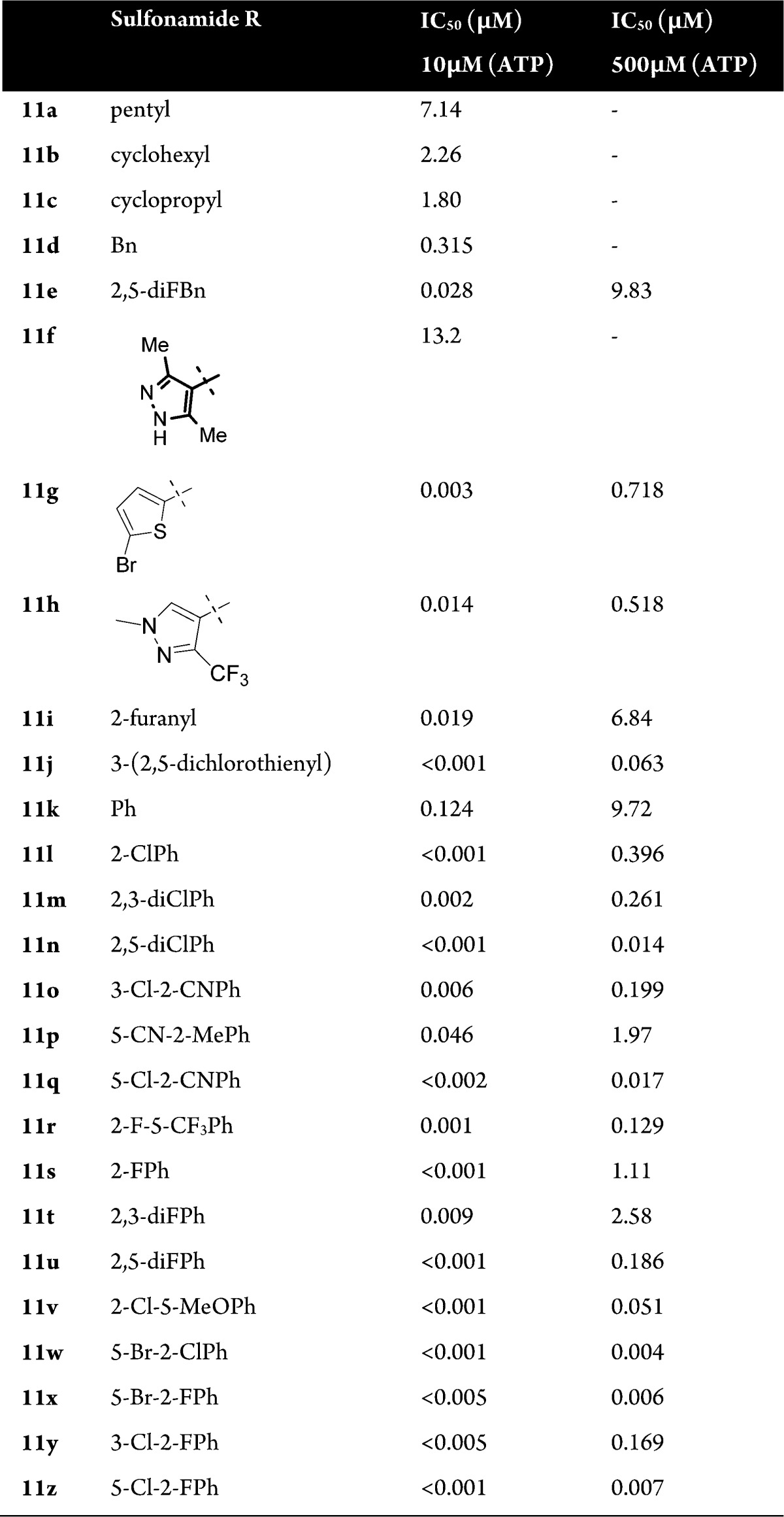

The overlay of these compounds is characterized by a high shape complementarity, whereas the alignment suggests that hydrogen bond interactions of the phenolic hydroxyl group may be geometrically replaced by the indazole heteroatoms (Figure 4). We then set out to investigate the structure–activity relationship (SAR) around these novel 3-aminoindazole hits using classical medicinal chemistry and library synthesis strategies. Initially, a library with 350 commercially available sulfonyl chlorides was condensed with the aniline building block 10 to explore the role of the distal sulfonamide ring (Scheme 1). This afforded approximately 330 3-aminoindazoles 11, after TFA induced Boc-deprotection, that were screened for SGK1 inhibitory activity in the presence of 10 and 500 μM ATP (Table 1). To our encouragement, a number of highly active SGK1 inhibitors with IC50s in the low nanomolar range were found in this initial library. Generally, alkylsulfonamides (11a–c) turned out to be only moderately active, whereas, e.g., aryl and heteroarylsulfonamides mostly exhibited activities in the nanomolar range at 10 μM ATP concentration.

Figure 4.

(a) Comparison of the color property (left) and molecular shape (right) of hydrazide 3 and the structurally distinct hit 3-aminoindazole 8. (b) ROCS-derived overlay of 3-aminoindazole 7 with compound 4 (ComboScore = 1.23) and 3-aminoindazole 8 with hydrazide 3 (ComboScore = 1.2). The overlay of the distal phenol and indazole moieties is in agreement with the ligand interaction model and suggests geometrically equivalent hydrogen bond donor/acceptor patterns to the binding site.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Sulfonamide Library.

Reactions and conditions: (a) Boc2O, DMAP, MeCN, reflux, 100%; (b) 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)aniline, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, dioxane–water, 100 °C, 2 h, 70%; (c) RSO2Cl, pyridine, CH2Cl2, rt. 15 h; (d) CF3CO2H, rt, 3 h.

Table 1. SGK1 Activity of Selected 3-Aminoindazoles 11.

In particular halide substituted benzenesulfonamides (11l–z) were found to be very potent SGK1 inhibitors with nanomolar potency in the presence of 10 μM ATP. We also determined the SGK1 activity at 500 μM ATP (100 Km) concentration and thus obtained the binding affinity in the presence of almost physiological levels of the endogenous ligand ATP. As shown in Table 1 most 3-aminoindazoles 11 displayed significantly reduced activities at 500 μM ATP concentration compared to 10 μM ATP concentration. This allowed us to discriminate further between the 3-aminoindazoles 11. Particularly the 2,5-dihalo substituted benzenesulfonamides such as 11n,w,x,z are strong SGK1 inhibitors at high ATP concentrations. Other small nonhalide substituents such as methyl, cyano, and methoxy also provided high activities, and it was generally observed that a 2,5-substitution pattern provided higher activities than the corresponding 2,3-substitution (11m vs 11n, 11o vs 11q, 11t vs 11u, and 11y vs 11z).

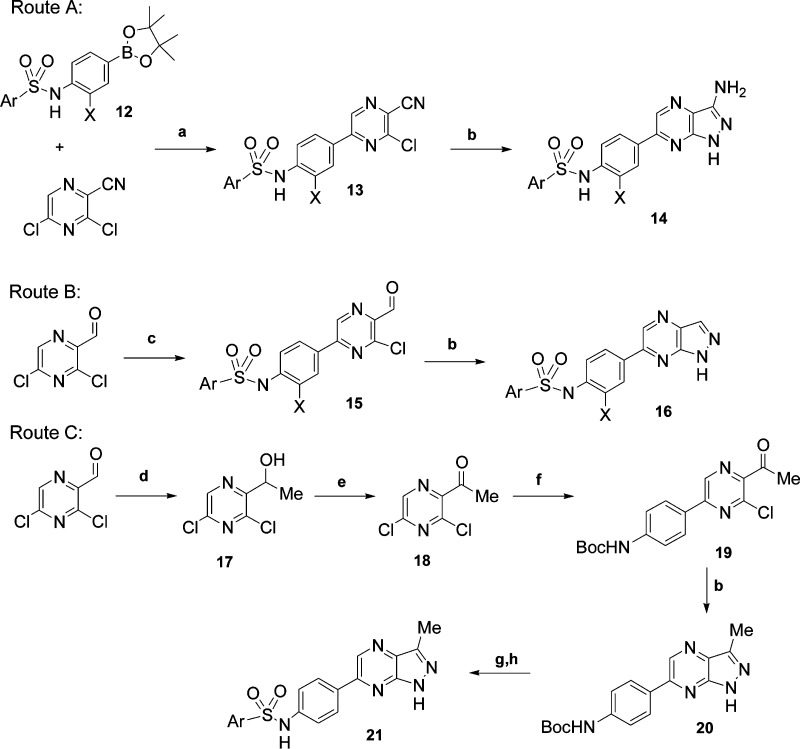

This initial library approach revealed important insights into the SAR around the arylsulfonamide ring, but most indazoles were found to have a low aqueous solubility of <0.001 mg/mL (pH = 7.4, 25 °C). Therefore, we turned our attention to the 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazine as hinge-binding motif as we expected this scaffold to have improved physicochemical properties such as higher solubility and lower lipophilicity (LogD). In addition, this also conferred structural novelty in the highly competitive kinase field. In order to compare 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines with indazoles as hinge-binders, a number of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14 were prepared according to Scheme 2 (Route A) as these could be directly compared to the 3-aminoindazoles 11 in Table 1. The synthesis proceeded through a straightforward condensation of the desired arylsulfonyl chloride and 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)aniline to afford boronic acid ester 12 in high yield. The second step was a Suzuki cross-coupling with commercially available 3,5-dichloro-pyrazine-2-carbonitrile that proceeded with high regioselectivity. Only trace amounts of the undesired regioisomer were observed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LCMS) in the reaction mixture. The regioselectivity is attributed to an increased steric shielding by the 2-cyano group of the 3-chloro substituent compared to the 5-chloro substituent. The Suzuki cross coupling generally afforded >70% isolated yield of 2-cyano-3-chloropyrazine 13 after purification, and no homocoupling of boronic acid ester 12 was observed by LCMS.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 1H-Pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 14, 16, and 21a.

Routes A, B, and C, reactions and conditions: (a) Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, dioxane–water, 100 °C, 3 h; (b) 35% N2H4 in water, iPrOH, 120 °C, MW, 20 min; (c) 12, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, dioxane–water, 100 °C, 1–3 h; (d) MeMgBr, THF, 5 °C, 10 min; (e) Dess–Martin periodinane, DCM, rt, 30 min; (f) 12, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Cs2CO3, dioxane–water, 100 °C, 1 h; (g) 4 N HCl in dioxane, rt, 2 h; (h) ArSO2Cl, pyridine, 100 °C, 30 min.

In order to obtain 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14, 2-cyano-3-chloropyrazines 13 were cyclized with 35% aqueous hydrazine by heating to 120 °C for 20 min under microwave radiation. This afforded the 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14 in moderate to good yields. These had comparable SGK1 activities as the corresponding 3-aminoindazoles 11, with the same arylbenzenesulfonamide residues (11j vs 14b, 11l vs 14d, 11m vs 14g, 11n vs 14h, 11q vs 14q, 11s vs 14k, 11u vs 14l, 11v vs 14i, and 11z vs 14n) and some highly potent compounds at high ATP concentration were obtained (Table 2). Especially 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14 having a 2-fluorobenzenesulfonamide moiety and a chloro, methyl, or methoxy substituent in the 5-position afforded highly active compounds confirming the SAR found for the 3-aminoindazoles 11. Attempts to break the symmetry of the central phenyl linker in order to improve solubility by introduction of an ortho-fluorine substituent (14t–v) were not successful, and therefore, no further optimization of the central phenyl linker was undertaken. We then reduced compound lipohilicity by replacing the aryl sulfonamide moiety of compound 14g with a secondary amide, but this resulted in a dramatic loss of activity to an IC50 = 3.54 μM at 10 μM ATP concentration.

Table 2. SGK1 Activity of Selected 1H-Pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 14, 16, and 21.

| sulfonamide Ar | X | IC50 (μM) 10 μM (ATP) | IC50 (μM) 500 μM (ATP) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14a | 1-naphtyl | H | 0.016 | 0.760 |

| 14b | 3-(2,5-dichlorothienyl) | H | 0.004 | 0.183 |

| 14c | 3-Cl-5-hydrazino-Ph | H | 0.196 | 0.639 |

| 14d | 2-ClPh | H | 0.014 | 0.910 |

| 14e | 2-Cl-3-FPh | H | 0.021 | 1.26 |

| 14f | 2,4-diClPh | H | 4.76 | |

| 14g | 2,3-diClPh | H | 0.003 | 0.442 |

| 14h | 2,5-diClPh | H | 0.005 | 0.025 |

| 14i | 2-Cl-5-MeOPh | H | 0.002 | 0.034 |

| 14j | 2-Cl-4-CF3Ph | H | 0.407 | 18.9 |

| 14k | 2-FPh | H | 0.022 | 1.49 |

| 14l | 2,5-diFPh | H | 0.015 | 0.730 |

| 14m | 5-Cl-2,4-diFPh | H | <0.002 | 0.041 |

| 14n | 5-Cl-2-FPh | H | 0.001 | 0.041 |

| 14o | 2-F-5-MePh | H | 0.002 | 0.039 |

| 14p | 2-F-5-MeOPh | H | <0.002 | 0.004 |

| 14q | 5-Cl-2-CNPh | H | 0.01 | 0.293 |

| 14r | 5-Me-2-CNPh | H | 0.003 | 0.061 |

| 14s | 5-MeO-2-CNPh | H | 0.002 | 0.040 |

| 14t | 2,3-diClPh | F | 0.003 | 0.182 |

| 14u | 2,5-diClPh | F | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| 14v | 5-Cl,2-FPh | F | 0.002 | 0.050 |

| 16a | 2,5-diClPh | H | 0.439 | 4.55 |

| 16b | 2,5-diClPh | F | 0.496 | 3.33 |

| 16c | 2,3-diClPh | F | 0.419 | 5.73 |

| 21a | 2,3-diClPh | 0.013 | 0.605 | |

| 21b | 2,5-diClPh | 0.002 | 0.011 | |

| 21c | 5-Cl-2-FPh | 0.004 | 0.088 | |

| 21d | 5-Cl-2-CNPh | 0.003 | 0.150 | |

| 21e | 5-Me-2-CNPh | 0.003 | 0.58 | |

| 21f | 2-F-5-MePh | 0.002 | 0.029 | |

| 21g | 2-Cl-5-MeOPh | 0.002 | 0.034 | |

| 21h | 2,5-diFPh | 0.029 | 1.34 |

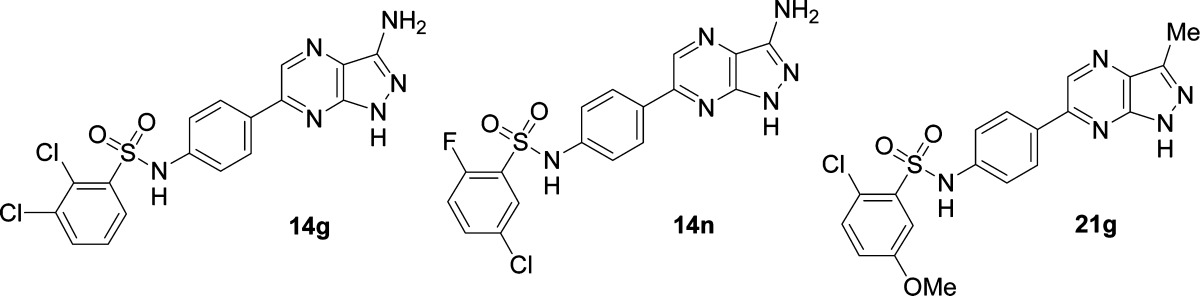

The reason for the observed affinity drop might be a change in geometry from the tetrahedral sulfonamide to the planar amide moiety that orients the 2,3-dichlorobenzene toward a mismatched position. In order to quantify the affinity contribution of a possible third hydrogen-bonding hinge contact, made by the 3-amino group, several analogues of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14 without the 3-NH2 substituent were prepared. We initially synthesized the 3-H substituted 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 16 from commercially available 3,5-dichloro-pyrazine-2-carbaldehyde by a Suzuki coupling with boronic acid ester 12 and subsequent cyclization of the pyrazole ring using hydrazine (Scheme 2, Route B). Again we observed a very good chemoselectivity in the Suzuki reaction, just as for the corresponding 3,5-dichloro-pyrazine-2-carbonitrile, in favor of the desired regioisomer 15. Indeed, the unsubstituted 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 16 prepared by this method displayed greatly reduced activity on SGK1 in the range of 3–5 μM at high ATP concentration. We then prepared a number of 3-methyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 21 according to Scheme 2 (Route C). Commercially available 3,5-dichloro-pyrazine-2-carbaldehyde was treated with an excess of MeMgBr under external cooling to keep the reaction temperature below 5 °C. This afforded quantitative conversion to the secondary alcohol 17 that was subsequently oxidized to methylketone 18 using Dess–Martin periodinane. Ketone 18 underwent a regioselective Suzuki coupling with Boc-protected 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)aniline to afford 19 that was cyclized to 3-methyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazine 20 with hydrazine under microwave irradiation. The aniline was deprotected and treated with the corresponding sulfonyl chlorides to afford methyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines 21a–h. These derivatives were found to be very potent SGK inhibitors with activities of <15 nM in the presence of 10 μM ATP, and many retained their high activity even in the presence of 500 μM ATP. For instance the 2,5-disubstituted phenylsulfonamides 21b, 21f, and 21g all exhibited activities below 35 nM in the presence of 500 μM ATP. In general it was found that the 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazines retained activity at high ATP concentrations compared to the indazoles 11, and we assume that additional protein–ligand interactions with the pyrazine ring nitrogens enable the improved binding kinetics. After optimizing the SGK1 inhibitors to very high levels of inhibitory activity we selected 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14g and 14n as well as methyl-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazine 21g for further in vitro profiling in order to obtain an overall profile of the compounds (Table 3). Generally all three compounds showed favorable calculated parameters, were Lipinski rule-of-5 compliant, possessed good physicochemical properties, and displayed LogD values from 2.0 to 2.7 and a high lipophilic ligand efficacy (LLE). The solubility in simulated gastric juice at pH = 5.0 (FeSSIF) was found to be acceptable for in vivo studies with oral application although the aqueous solubility was moderate. The compounds proved to be metabolically stable in human liver fractions and also showed excellent predicted absorption properties in Caco-2 cell monolayers (Table 3). In addition, no significant CYP3A4 inhibition was observed. The 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines 14g and 14n also showed an acceptable SGK isoform selectivity with a good activity on hSGK2 and a moderate activity on the hSGK3.

Table 3. Physicochemical and ADME Properties of 14g,n and 21g.

| compd | 14g | 14n | 21g |

|---|---|---|---|

| MW | 435 | 418 | 429 |

| LLE 10/500 μM ATP | 6.2/4.1 | >6.7/5.4 | 6.0/4.8 |

| LogD (pH 7.4, 25 °C) | 2.28 | 2.01 | 2.70 |

| CLogP | 4.38 | 4.09 | 4.03 |

| PSA (Å2) | 135 | 135 | 118 |

| H-bond donors | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| H-bond acceptors | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| rotatable bonds | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| aqueous solubility (pH = 7.4, 25 °C) | 0.011 mg/mL | <0.001 mg/mL | <0.001 mg/mL |

| FeSSIFb solubility (pH = 5.0, 25 °C) | 0.069 mg/mL | 0.075 mg/mL | 0.038 mg/mL |

| IC50 hSGK1 10/500 μM ATP | 0.003/0.442 μM | 0.001/0.041 μM | 0.002/0.034 μM |

| IC50 hSGK2 500 μM ATP | 0.924 μM | 0.128 μM | nd |

| IC50 hSGK3 500 μM ATP | 23.3 μM | 3.1 μM | nd |

| IC50 phosphorylation of GSK3β in U2OS cells | 1.4 μM | 0.69 μM | nd |

| metabolic degradation in human microsomesc | 14% | 8% | 27% |

| intrinsic clearance in human hepatocytes (mL/h/106 cells) | 0.051 | nd | 0.150 |

| Caco2 permeability (×10–7 cm/s) | 133 | 124 | 135 |

| CYP3A4 inhibition IC50a (M/T) | >30/14.5 μM | >30/28.6 μM | 26.8/18.6 μM |

| kinase selectivity: kinases with >50% inhibition at 1 μM | 1/60 | 0/60 | nd |

Incubated at 37 °C for 10–30 min at 0.3–30 μM. M = midazolam site; T = testosterone site.

Simulated gastric juice in the fed state.

Percent degradation after 20 min incubation (see Supporting Information for details).

These compounds also displayed cellular activity in a SGK1-dependent phosphorylation of GSK3β assay in U2OS cells with activities of 1.4 and 0.69 μM, respectively. As for all ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors, off-target selectivity needs to be established, as cross kinase target promiscuity is frequently observed28,29 due to the highly conserved ATP binding pocket. This type of promiscuity has been held responsible both for genotoxicity and cardiotoxicity30,31 of drugs, thus emphasizing the need to implement predictive off-target profiling strategies.32 The selectivity against other kinases was found to be excellent for 14g and 14n when tested against a representative panel of 60 potential target and antitarget protein kinases (see Supporting Information) across the human kinome. Only AMP dependent kinase was inhibited with >50% at 1 μM concentration in the presence of 2 Km ATP concentration. We attribute this excellent target selectivity to the highly rigid structure of the chemical scaffold that makes the geometrical position of the interaction points very specific and leaves little conformational flexibility to adapt to other kinase binding pockets. A similar clean profile was obtained in a profiling panel of 33 selected antitargets (see Supporting Information).

The 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amine 14g was selected for in vivo profiling due to its favorable in vitro profile, and a pharmacokinetic study in rat was conducted to determine the PK profile. After a single oral administration of 3.0 or 30 mg/kg, blood samples were collected for up to 24 h, and the key pharmacokinetic parameters were determined as an average with n = 3 for each sampling point (Table 4).

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic Parameters of 14g.

| 3 mg/kg |

30 mg/kg |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plasma | kidney | liver | plasma | kidney | liver | |

| Cmaxa | 3.88 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 29.9 | 9.1 | 13.4 |

| Tmax (h) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.0 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 5.2 |

| AUC0–24hb | 23.0 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 270 | 98 | 170 |

| tissue/plasma ratioc | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.63 | ||

In units of μg·h/mL or μg·h/g.

In units of μg/mL or μg/g.

Calculated using AUC.

The maximum plasma concentration in the 3 mg/kg group was obtained after 2 h where a level of Cmax = 3.88 μg/mL was observed, and the half-life was determined to be 3 h indicating a high plasma stability and a moderate clearance. After 24 h plasma levels were less than 1% of Cmax indicating a complete clearance. In the 30 mg/kg group the maximum plasma concentration (mean value 29.9 μg/mL) was found 4 h after administration, and again, elimination was complete 24 h after administration. The half-life in plasma was found to be 4.1 h, and a dose proportionality between the 3 and 30 mg/kg doses was observed. Distribution into tissues was low, the highest concentrations were found in liver followed by kidney and brain (data not shown).

In summary, we have developed highly active ATP competitive inhibitors of serum glucocorticoid-regulated kinase-1 that exhibited low nanomolar activity even in the presence of physiological levels of ATP. The compounds were also found to have attractive physicochemical, ADME, and PK properties as well as an exceptionally high kinase selectivity.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are expressed to Silke Herok-Schoepper, Astrid Sihorsch, Günter Frey, and Karl-Heinz Herget-Jürgens for excellent technical assistance and to Jean-Christophe Carry for providing the synthetic route to the 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyrazin-3-amines.

Supporting Information Available

Representative experimental procedures for synthesis, in silico methods, biochemical assays, and analytical data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bruhn M. A.; Pearson R. B.; Hannan R. D.; Sheppard K. E. Second AKT: the rise of SGK in cancer signalling. Growth Factors 2010, 28, 394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F.; Larrea M. D.; Doughty C.; Kwiatkowski D. J.; Squillace R.; Slingerland J. M. mTOR-raptor binds and activates SGK1 to regulate p27 phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F.; Artunc F.; Vallon V. The physiological impact of the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2009, 18, 439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F.; Bohmer C.; Palmada M.; Seebohm G.; Strutz-Seebohm N.; Vallon V. (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F.; Görlach A. Heterocyclic indazole derivatives as SGK1 inhibitors, WO2008138448. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat 2010, 2, 129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anacker C.; Cattaneo A.; Musaelyan K.; Zunszain P. A.; Horowitz M.; Molteni R.; Luoni A.; Calabrese F.; Tansey K.; Gennarelli M.; Thuret S.; Price J.; Uher R.; Riva M. A.; Pariante C. M. Role for the kinase SGK1 in stress, depression, and glucocorticoid effects on hippocampal neurogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 8708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehner M.; Hadjihannas M.; Weiske J.; Huber O.; Behrens J. Wnt signaling inhibits Forkhead box O3a-induced transcription and apoptosis through up-regulation of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 19201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopjani M.; Alesutan I.; Wilmes J.; Dermaku-Sopjani M.; Lam R. S.; Koutsouki E.; Jakupi M.; Foller M.; Lang F. Stimulation of Na+/K+ ATPase activity and Na+ coupled glucose transport by β-catenin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BelAiba R. S.; Djordjevic T.; Bonello S.; Artunc F.; Lang F.; Hess J.; Gorlach A. The kinase Sgk-1 is involved in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens V. A.; Saad S.; Poronnik P.; Fenton-Lee C. A.; Polhill T. S.; Pollock C. A. The role of SGK-1 in angiotensin II-mediated sodium reabsorption in human proximal tubular cells. Nephrol., Dial., Transplant. 2008, 23, 1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S. V.; Kathpalia P. P.; Rajagopal M.; Charlton C.; Zhang J.; Eaton D. C.; Helms M. N.; Pao A. C. Epithelial sodium channel regulation by cell surface-associated serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkl J.; Mia S.; Meissner A.; Ahmed M. S.; Feger M.; Elvira B.; Walker B.; Alessi D. R.; Alesutan I.; Lang F. PKB/SGK-resistant GSK-3 signaling following unilateral ureteral obstruction. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2013, 38, 156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace K.; Long Q.; Fairhall E. A.; Charlton K. A.; Wright M. C. Serine/threonine protein kinase SGK1 in glucocorticoid-dependent transdifferentiation of pancreatic acinar cells to hepatocytes. J. Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond M.; Washburn D. G.; Hoang H. T.; Manns S.; Frazee J. S.; Nakamura H.; Patterson J. R.; Trizna W.; Wu C.; Azzarano L. M.; Nagilla R.; Nord M.; Trejo R.; Head M. S.; Zhao B.; Smallwood A. M.; Hightower K.; Laping N. J.; Schnackenberg C. G.; Thompson S. K. Design and synthesis of orally bioavailable serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 (SGK1) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4441–4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merck patents WO2005/037773, WO2006/105850, WO2005/123688, WO2006/105865.

- Towhid S. T.; Liu G. L.; Ackermann T. F.; Beier N.; Scholz W.; Fuchss T.; Toulany M.; Rodemann H. P.; Lang F. Inhibition of colonic tumor growth by the selective SGK inhibitor EMD638683. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldenhuys W. J.; Talasila P. K.; Sadana P. Identification of a novel serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase-1 (SGK1) ligand from virtual screening. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 5675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazaré M.; Halland N.; Schmidt F.; Weiss T.; Dietz U.; Hofmeister A.. WO2013041119.

- Oprea T.; Matter H. Integrating virtual screening in lead discovery. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2004, 8, 349–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider G. Virtual screening: an endless staircase?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger D. M.; Evers A. Comparison of structure- and ligand-based virtual screening protocols considering hit list complementarity and enrichment factors. ChemMedChem 2010, 5, 148–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- After preparation of this letter, structures of other SGK1 inhibitors were published.Ortuso F.; Amato R.; Artese A.; D’antona L.; Costa G.; Talarico C.; Gigliotti F.; Bianco C.; Trapasso F.; Schenone S.; Musumeci F.; Botta L.; Perrotti N.; Alcaro S. In silico identification and biological evaluation of novel selective serum/glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 inhibitors based on the pyrazolo-pyrimidine scaffold. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1828–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B.; Lehr R.; Smallwood A. M.; Ho T. F.; Maley K.; Randall T.; Head M. S.; Koretke K. K.; Schnackenberg C. G. Crystal Structure of Inactive SGK1 in Complex with AMP-PNP. Protein Sci. 2007, 16, 2761–2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OpenEye Scientific Software; www.eyesopen.com.

- Bostrom J.; Greenwood J. R.; Gottfries J. Assessing the performance of OMEGA with respect to retrieving bioactive conformations. J. Mol. Graphics Model. 2003, 21, 449–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchmair J.; Distinto S.; Markt P.; Schuster D.; Spitzer G. M.; Liedl K. R.; Wolber G. J. How to optimize shape-based virtual screening: choosing the right query and including chemical information. Chem. Inf Model. 2009, 49, 678–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The compounds were tested for serum glucocorticoid-regulated kinase-1 (SGK1) inhibitory activity in a substrate phosphorylation assay. The phosphorylated substrate peptide and nonphosphorylated peptide are separated with caliper life sciences (PerkinElmer) lab-chip technology based on a microfluidic method. The substrate peptide is attached to a fluo-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein)-RPRAATF-NH2 fluorescent group facilitating detection by laser excitation and readout of the fluorescence signal. Recombinant human SGK1 enzyme was expressed in a baculovirus system and activated by human PDK1.

- Jester B. W.; Gaj A.; Shomin C. D.; Cox K. J.; Ghosh I. Testing the promiscuity of commercial kinase inhibitors against the AGC kinase group using a split-luciferase screen. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov O.; Marsden B.; Pogacic V.; Rellos P.; Muller S.; Bullock A. N.; Schwaller J.; Sund-strom M.; Knapp S. A systematic interaction map of validated kinase inhibitors with Ser/Thr kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104, 20523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner S.Kinases as antitargets in genotoxicity. In Polypharmacology in Drug Discovery; Peters J. U., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hasinoff B. B.; Patel D. The lack of target specificity of small molecule anticancer kinase inhibitors is correlated with their ability to damage myocytes in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 2492132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F.; Matter H.; Hessler G.; Czich A. Predictive in silico off-target profiling in drug discovery. Future Med. Chem. 2014, 63295–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.