Summary

Many uncertain and inconsistent etiologies of cerebral aneurysmal rupture including a wide spectrum of factors have been reported. Our recent observation discloses the potential new factor of cerebral aneurysm rupture with cerebral venous pressure gradient. We retrospectively reviewed 52 cases treated with coil embolization with or without cerebral aneurysmal rupture. Seventeen males and 30 females were recruited in this study. Quantitative color-coded cerebral angiography was performed during coil therapeutic procedures to measure cerebral venous circulation. Ruptured cases had shorter and symmetrical cerebral venous circulation time (P <0.05). In addition, an asymmetrical venous outflow pattern was critical for aneurysmal rupture. Non-ruptured cases tended to have slower and asymmetrical cerebral venous circulation compared with rupture cases. Symmetrical and shorter cerebral venous circulation in the dysplasia venous outlet may be a potential new factor for cerebral aneurysm rupture.

Keywords: cerebral aneurysm, DSA i-Flow, venous outflow pattern, circulation time

Introduction

The variable etiologies of cerebral aneurysm rupture have been extensively published including age, gender, genetics, smoking, size, site, configuration, flow profile and wall stress and other factors 1,4-6,10-12. However, the implication of those factors in clinical practice may be very inconsistent 8,10-18. In the past, we have observed interesting data of cerebral aneurysm rupture likely relating to asymmetry of the dural sinus especially in female populations 9,12 and recently encountered one patient with aneurysm rupture related to venous pressure gradient 20. Previous publications encouraged us to review all cases of cerebral aneurysm with or without rupture to validate this observation 9,12,21. Quantitative venous pressure measurement relied on invasive catheter placement in the past 2,3,7,9,12. With improvements to imaging techniques and software, the venous pressure gradient may be measured by phase contrast MRI but it is not precise or consistent 12. Color-coded quantitative cerebral angiography which can measure circulation time and pressure gradient was used in this study as in our previous report 20,21,23.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

We retrospectively reviewed 84 cases with a clinical suspicion of cerebral vascular diseases for aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage from the file of Chang-Hua Christian Hospital from December 2008 to October 2013. Twenty one (N=21) with trauma and dissection and 11 with incomplete imaging were excluded, so 52 subjects were enrolled in the study. All of the human experimental procedures followed the ethical standards of the Chang-Hua Christian Hospital and were approved by the institutional review committee (Protocol number: CCH 080106). Informed consent was obtained from each subject during the therapeutic procedure.

Measurement of cerebral circulation time

Quantitative color-coded cerebral angiography was performed with bilateral carotid and vertebral arteries to evaluate aneurysm characteristics and circulation time. The injection rate was constant as 5cc/s for 1.5 s. The diagnostic procedures include working biplane digital subtraction angiography (DSA with an injection rate of 3 cc/s for 6 s and 3D DSA. The biplane angiography suite (AXIOM-Artis®; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) was used for this DSA study. Post-processing software (syngo iFlow®; Siemens) was used to color-code the DSA, according to their time to Tmax in seconds. The Tmax of any selected region of interest on DSA was defined as the time point when the attenuation of the x-ray reached its maximum along the angiographic frames. The diameter of a region of interest was the caliber of a selected vessel. The reference time point was defined as the imaging time of the selected mask of the angiographic frames. Eight ROIs on AP and 12 ROIs on lateral views of DSA were defined. The Tmax values of dural sinuses and jugular veins in AP and LAT were defined respectively. Cerebral circulation time (CCT) was measured from the distal cervical internal carotid artery to the proximal jugular vein junction with the sigmoid sinus, and cerebral venous circulation (ΔCCT) being venous Tmax minus arterial Tmax 18,20,21,23. The measurements were by the consensus of the same two experienced neuroradiologists who analyzed the DSA datasets.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean+/-SD. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package, version 17.0 (Chicago, Ill, USA). Differences were evaluated using the Student T test, Mann-Whitney-U test.

Results

We retrospectively reviewed 84 patients from the file with saccular aneurysms who received endovascular treatment. Overall 52 cerebral aneurysm patients were enrolled including non-ruptured and acute ruptured aneurysms of the anterior circulation. We analyzed diameters and outflow patterns of dural sinuses and internal jugular veins. Bilateral cerebral venous outflow patterns were divided into three patterns: symmetrical (N=18), asymmetry/aplasia (N=25) and unilateral atresia (N=9). Siemens quantitative color-coded cerebral DSA i-Flow software was used to evaluate bilateral cerebral flow circulation time. We found that aplasia or atresia of the left dural sinus and internal jugular vein had longer cerebral venous circulation time which implied slower venous outflow rate (P-trend=0.035). The caliber of left internal jugular vein is also smaller compared with the contralateral right side (P=0.003). The cerebral venous circulation of asymmetrical left side is slower than the symmetrical right side possibly due to the smaller caliber of left venous outflow (Table 1). We further investigated and compared the non-ruptured (N=13) and ruptured (N=39) aneurysm groups. In the non-ruptured group, there was no statistical difference between the internal jugular vein diameter and cerebral venous circulation time in either symmetrical or asymmetrical outflow patterns. In the acute ruptured group, the asymmetrical group (aplasia or atresia) showed a decrease with faster cerebral venous circulation time (P=0.021) and small internal jugular vein diameter (P=0.046) compared with the symmetrical pattern. These data suggest that with an asymmetrical cerebral venous outflow pattern, especially stenotic dural sinus and hypoplastic internal jugular vein, the shorter cerebral venous circulation times imply faster venous outflow and also possible higher ipsilateral venous pressure gradient. This pattern correlates to acute cerebral aneurysm rupture patients (Table 2). The cases of acute ruptured aneurysms with symmetrical venous outflow also had symmetrical and shorter cerebral venous circulation time (Figures 1 and 2). However, there were two outlier non-rupture cases with faster and bilateral symmetrical cerebral venous circulation (Figure 5).

Table 1.

Cerebral venous circulation time.

| N | ΔCCT | SD | SE | |

| Right Circulation: Symmetry (mm) |

18 | 10.885 | 2.439 | 0.487 |

| Asymmetry (mm) | 34 | 12.101 | 2.452 | 0.577 |

| Left Circulation: | ||||

| Symmetry (mm) | 18 | 10.680 | 2.818 | 0.445 |

| Asymmetry (mm) | 34 | 10.831 | 2.151 | 0.507 |

| Diameter of Jugular Veins: Symmetry (mm) |

Right: 9.13 | Left: 8.08 | ||

| Asymmetry (mm) | Right: 8.81 | Left: 6.11 | ||

| CCT, cerebral circulation time; SD, standard deviation; SE standard error. | ||||

Table 2.

Cerebral venous circulation time of ruptured and unruptured cases.

| N | Mean±SD | P-Value | |

| Unruptured Cases: | 13 | ||

| Right ΔCCT | 11.32±3.88 (5.86-19.67) | 0.225 | |

| Left ΔCCT | 12.49±3.92 (5.87-21.33) | ||

| Ruptured Cases: | 39 | ||

| Right ΔCCT | 11.12±1.87 (8.13-14.67) | 0.005 | |

| Left ΔCCT | 11.54±2.22 (7.46-15.33) | ||

| *P <0.05. | |||

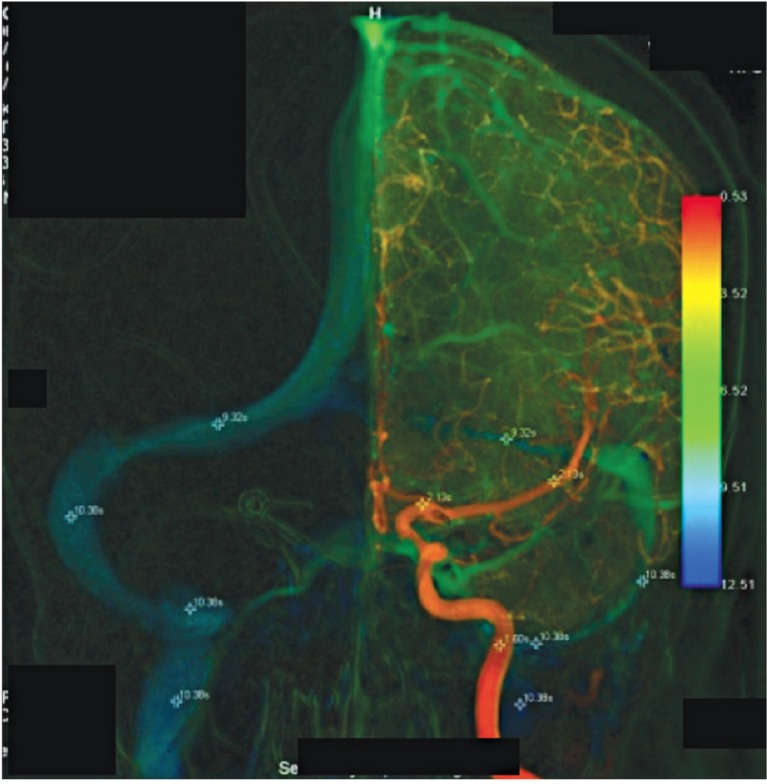

Figure 1.

CT disclosed subarachnoid hemorrhage, while CT angiography disclosed a left Pcom aneurysm. The patient was then transferred for endovascular therapeutic coiling. The aneurysm was successfully embolized with coils. There were similar bilateral cerebral venous circulations despite severe hypoplasia of the left transverse and sigmoid sinuses and jugular vein (ΔCCT10.33-2.13=8.20).

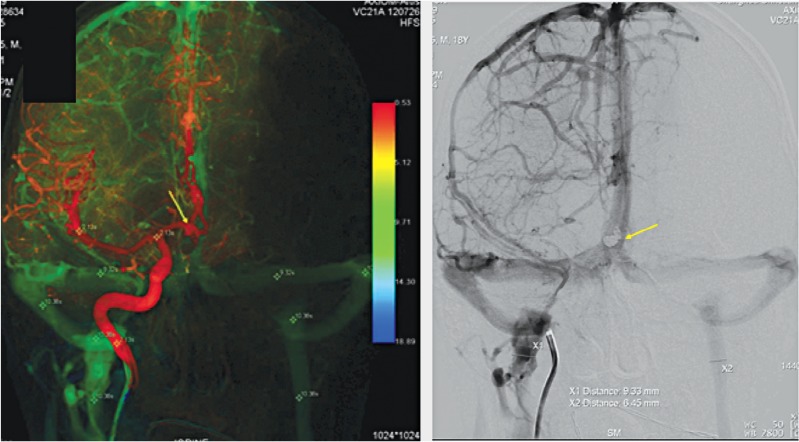

Figure 2.

CT angiography identified a ruptured Acom aneurysm confirmed by cerebral angiography. Endovascular therapy was then performed with successful coil embolization (arrow). Venous outflow was very similar with only mild asymmetry but the bilateral cerebral venous circulations were symmetric with ΔCCT (10.38-2.13=8.25).

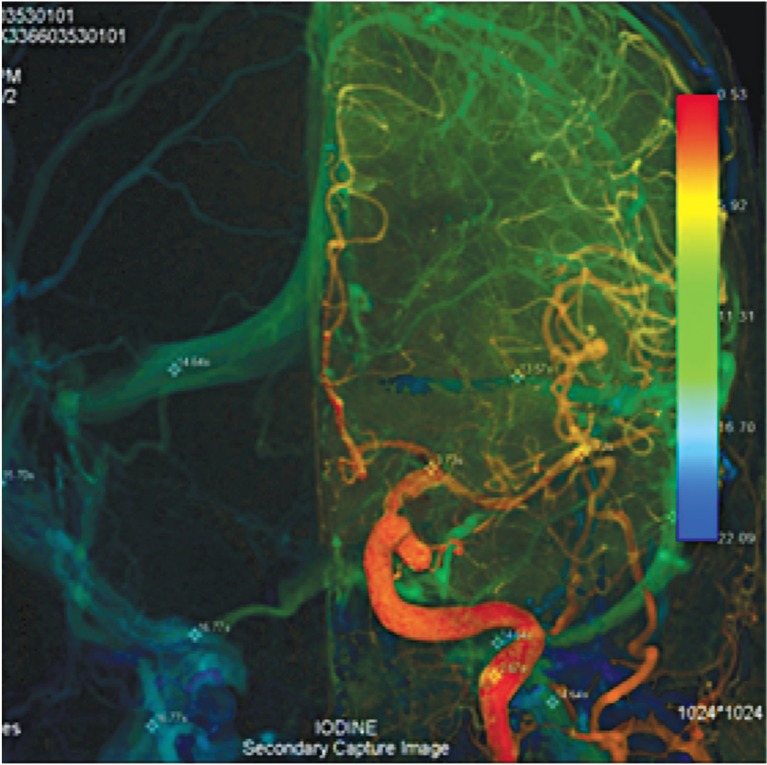

Figure 3.

Imaging studies disclosed a ruptured Acom aneurysm. The patient then underwent successful coil embolization the following day about 16 hours after onset of subarachnoid hemorrhage. The left sigmoid sinus is smaller than the right, but bilateral cerebral venous circulations being symmetric with ΔCCT (15.67-3.03=12.64).

Figure 4.

No imaging or clinical finding of subarachnoid hemorrhage was noted. The patient was referred for endovascular therapy. The aneurysm was successfully embolized with coils. Despite asymmetry of the left dural sinus and jugular vein, cerebral venous circulations were very different on both sides, as right ΔCCT16.77-3.73=13.04 and left ΔCCT 14.64-3.73=10.81.

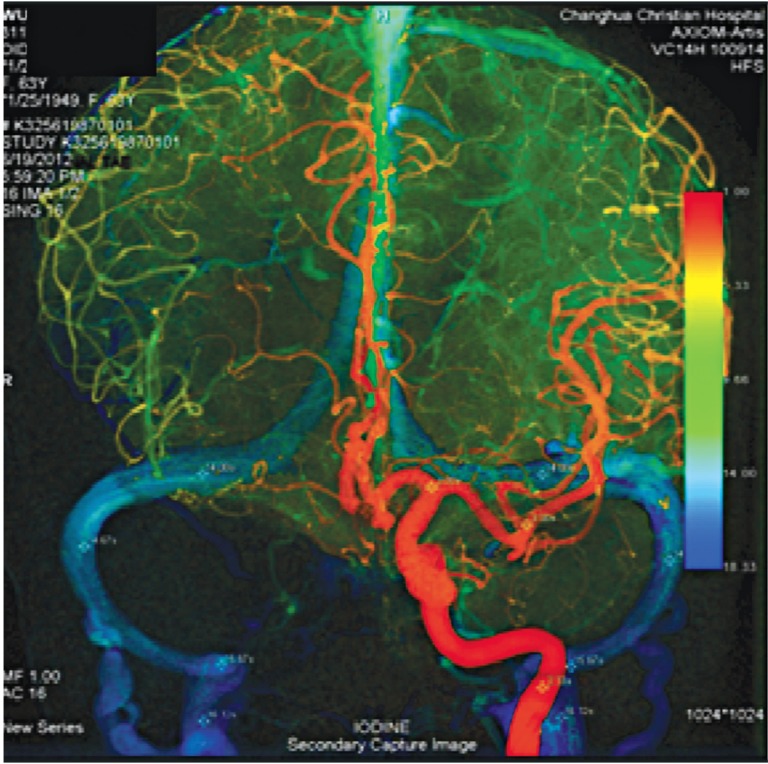

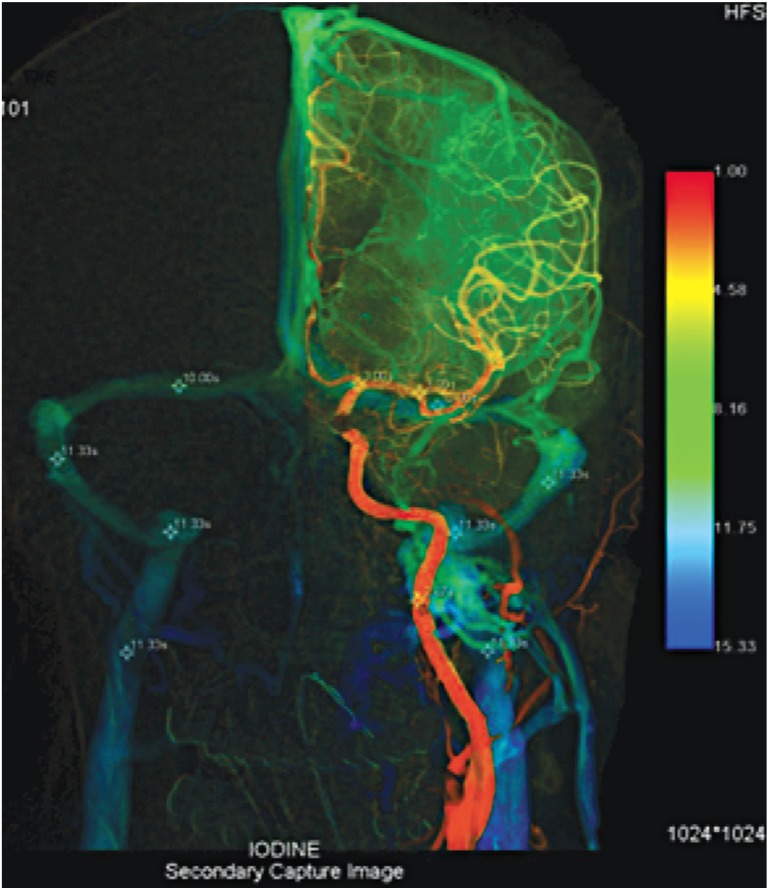

Figure 5.

This patient suffered left orbital ptosis from incidental unruptured left Pcom aneurysm (arrow). She was then treated with endovascular coiling embolization after consulting with her family. Symmetrical bilateral cerebral venous circulation time with asymmetry left venous outflow, ΔCCT (11.33-3.00=8.33).

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

A 62-year-old woman presented with sudden severe headache with extensive subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ruptured left posterior communicating artery (Pcom) aneurysm was discovered by CT angiography (CTA). She was then transferred for endovascular therapeutic coiling. The aneurysm was successfully embolized with coils. There were similar bilateral cerebral venous circulations despite severe hypoplasia of the left transverse and sigmoid sinuses and jugular vein (ΔCCT10.33-2.13=8.20) (Figure 1).

Case 2

An 18-year-old male presented with acute onset of lost consciousness with severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. CTA identified a ruptured anterior communicating artery (Acom) aneurysm as confirmed by cerebral angiography. Endovascular therapy was then performed with successful coil embolization (arrow). Venous outflow was very similar with only mild asymmetry but bilateral cerebral venous circulations were symmetric with ΔCCT (10.38-2.13=8.25) (Figure 2).

Case 3

A 63-year-old woman presented with sudden onset of severe headache and mental changes from acute subarachnoid hemorrhage around midnight. Imaging studies discovered a ruptured Acom aneurysm. She then underwent successful coil embolization the following day about 16 hours after onset of SAH. The left sigmoid sinus is smaller than the right, but bilateral cerebral venous circulations were symmetric with ΔCCT (15.67-3.03=12.64) (Figure 3).

Case 4

A 73-year-old woman was discovered with a left Pcom aneurysm from a routine physical check-up with no imaging or clinical finding of subarachnoid hemorrhage. She was referred for endovascular therapy. The aneurysm was successfully embolized with coils. Despite asymmetry of the left dural sinus and jugular vein, cerebral venous circulations were very different on both sides, as right ΔCCT16.77-3.73=13.04 and left ΔCCT 14.64-3.73=10.81 (Figure 4).

Case 5

A 54-year-old woman presented with incidental unruptured left Pcom aneurysm from left ptosis (arrow). She had a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. She was then treated with endovascular coiling after consulting with her family. Symmetrical bilateral cerebral venous circulation time with asymmetry left venous outflow, ΔCCT (11.33-3.00=8.33) (Figure 5).

Discussion

We recently encountered interesting data on cerebral aneurysmal rupture that may be related to the asymmetry of the dural sinus with an increased pressure gradient particularly in female populations 9,12,21. Quantitative venous pressure measurement relied on invasive catheter placement in the past 2,3,7,9,12. Karahalios et al. reported that elevated intracranial venous pressure may be due to a stenotic cerebral venous outlet. Cerebral venous hemodynamics in our patients who had venous pressure gradient at the hypoplasia side of the venous system seem to be compatible with their statement 3,21. From our preliminary data, aneurysm rupture may be related to this phenomenon. Although our male cases appear to be slight younger than the female patients, the average age is very similar with less than two years' difference 9,12.

The quantitative cerebral venography of the rupture cases had similar and symmetrical or very mild differences in cerebral circulation time between asymmetrical dural sinuses (Table 1). The non-ruptured cases had a significant circulation time difference of 1.2 seconds. The ruptured cases had similar or no difference in cerebral circulation time from the asymmetrical dural sinuses: the smaller side with faster circulation should encounter a higher pressure gradient. The data showed a very significant difference in cerebral circulation time between the ruptured patients and non-ruptured patients (Table 2 and Figure 3). Patients with acute rupture may experience higher heart rates with higher blood pressure leading to faster cerebral circulation. However, this shortening of cerebral venous circulation time may be due to other factors too. Faster venous circulation was also described by Lin et al. as sign of inducing hyperperfusion from carotid stenting 23. Therefore these shorter cerebral venous circulation times may not be solely from subarachnoid hemorrhage following acute aneurysmal rupture.

One of our recently reported cases was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of therapeutic options for unruptured cerebral aneurysm. The initial cerebral angiography disclosed a lobulated aneurysm and atresia of the left transverse sinus as well as severe hypoplasia of the left sigmoid sinus. Quantitative cerebral venography at the time of aneurysm evaluation showed bilateral symmetrical and similar venous flow rates on both sides of the sigmoid sinuses and jugular veins. During conversation with the family and while analyzing therapeutic options, the patient suddenly suffered massive subarachnoid hemorrhages. Quantitative cerebral venography at the time of aneurysm rupture also showed similar symmetrical venous flow rates on both sides. With flow dynamics, in order to push blood flow through the aplastic small dural sinus equal to the contralateral larger side, a smaller diameter vessel requires higher pressure to achieve the same flow as a dominant and larger vessel. This observation confirmed our theory of a higher pressure gradient during this aneurysm rupture. This particular case illustrates an unusual presentation of pressure gradient of cerebral venous flow associated with acute rupture of cerebral aneurysm 21.

Illustrative Case 1 had a ruptured left Pcom aneurysm. The cerebral venous circulation was equal on both sides even with severe dural sinus hypoplasia by quantitative cerebral angiography. Case 2 and Case 3 had an acute ruptured Acom aneurysm with mild asymmetry of the dural sinus and jugular vein, but the cerebral venous circulation were symmetrical and shorter than in the unruptured case (Figure 4). These examples further confirm that similar and equal cerebral venous circulation may be a marker of potential aneurysm rupture due to an increased pressure gradient. With our previous observation, a symmetrical cerebral venous circulation may be a potential indicator of rupture of cerebral aneurysm 20,21. This is even more critical with ipsilateral aplasia of cerebral venous outflow 9,12. Two outlier cases had symmetrical cerebral venous circulation with unruptured aneurysms at the time of coil treatment (Figure 5). Although these two cases were classified as unruptured, the aneurysms could be treated on time with embolization before potential rupture. Case 3 had a slightly longer cerebral venous circulation time, perhaps due to the timing between onset of SAH and cerebral angiography, yet the symmetrical circulation time was no different.

The management of unruptured cerebral aneurysms remains somewhat dissimilar and debatable giving rise to controversy on many occasions. Wide and varied factors are frequently placed in the evaluation for treatment of unruptured cerebral aneurysms, yet decisions may be very inconsistent and perhaps inconclusive 1,3,5,7,10-21. Asymmetry of the dural sinus may be considered a potential risk factor for aneurysm rupture as reported previously 8,11. However, those observations did not have angiographic validation until our current data. The current findings and data may add another potentially important factor to manage unruptured cerebral aneurysms based on the pressure gradient from asymmetry of the dural sinus with cerebral venous outflow as a potential increase in the venous pressure gradient. More aggressive treatment of aneurysms may be warranted in patients with ipsilateral sinus hypoplasia or atresia and with shorter and symmetrical circulation time 18-22. Color-coded i-Flow quantitative cerebral angiography may be performed to evaluate the venous circulation with pressure gradient in those cases with asymmetrical dural sinuses with equal/shorter circulation time to avoid the risk of sudden rupture 19,20,22.

Certainly, our data do not measure the venous pressure gradient directly, but rather shorter and symmetric circulation time between asymmetry of the dural sinus reflecting the pressure gradient as by flow dynamic equation 12,21,23. Tmax may not be consistent, but we have tried to measure the same location of each vessel with the consensus of two experienced neuroradiologists (KWL and FYT) to minimize the difference. Our data are similar to recent report showing that shortening of the cerebral venous circulation may induce hyperperfusion with parenchymal change as increasing venous pressure 23. The pressure gradient was also documented as inversely proportional to the diameter of the venous sinus. Thus the pressure gradient reflected by shortening and symmetry of the cerebral venous circulation may be considered another possible potential factor of cerebral aneurysmal rupture.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Camilla Smith for proof reading, correcting grammar and typographic errors.

References

- 1.Dell S. Asymptomatic cerebral aneurysm: assessment of its risk of rupture. Neurosurgery. 1982;10(2):162–166. doi: 10.1097/00006123-198202000-00002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai FY, Wang AM, Matovich VB, et al. MR Staging of acute dural sinus thrombosis: correlation with venous pressure measurements and implications for treatment and prognosis. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1021–1029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karahalios DG, Rekate HL, Khayata MH, et al. Elevated intracranial venous pressure as a universal mechanism in pseudotumor cerebri of varying etiologies. Neurology. 1996;46:198–202. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.198. doi: 10.1212/WNL.46.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rinkel GJE, Djibuti M, Algra A, et al. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms. A systematic review. Comments, opinions, and reviews. Stroke. 1998;29:251–256. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.251. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.1.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman JA, Piepgras DG, Pichelmann MA, et al. Small cerebral aneurysms presenting with symptoms other than rupture. Neurology. 2001;57:1212–1216. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.7.1212. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.7.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vindlacheruvu RR, Mendelow AD, Mitchell P. Risk-benefit analysis of the treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:234–239. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031930. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.031930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai FY, Kostanian VJ, Rivera MB, et al. Cerebral venous congestion as indication for thrombolytic treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:675–687. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9046-1. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wermer MJH, van der Schaaf IC, Algra A, et al. Risk of rupture of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in relation to patient and aneurysm characteristics. An updated meta-analysis. Stroke. 2007;38:1404–1410. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260955.51401.cd. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260955.51401.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai FY, Nguyen B, Lin WC, et al. Endovascular procedures of cerebral venous diseases. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2008;101:83–86. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-78205-7_14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-211-78205-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventikos Y, Holland EC, Bowker TJ, et al. Computational modelling for cerebral aneurysms: risk evaluation and interventional planning. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:S62–S71. doi: 10.1259/bjr/14303482. doi: 10.1259/bjr/14303482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman M, Smietana J, Hauck E, et al. Size ratio correlates with intracranial aneurysm rupture status. A prospective study. Stroke. 2010;41:916–920. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.574244. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.574244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai FY, Yen A, Guo WY, et al. Venous hypertension and cerebral aneurysm rupture. Neuroradiol J. 2011;24:133–144. doi: 10.1177/197140091102400120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato K, Yoshimoto Y. Risk Profile of intracranial aneurysms rupture rate is not constant after formation. Stroke. 2011;42:3376–3381. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625871. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lua G, Huanga L, Zhanga XL, et al. Influence of hemodynamic factors on rupture of intracranial aneurysms: patient-specific 3D mirror aneurysms model computational fluid dynamics simulation. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1255–1261. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2461. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlak MHM, Rinkel GJE, Greebe P, et al. Trigger factors and their attributable risk for rupture of intracranial aneurysms. A Case-crossover study. Stroke. 2011;42:1878–1882. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606558. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.606558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiang JP, Tremmel M, Kolega J, et al. Newtonian viscosity model could overestimate wall shear stress in intracranial aneurysm domes and underestimate rupture risk. J Neurointervent Surg. 2012;4:351–357. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010089. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazzaro MA, Ouyang B, Chen M. The role of circle of Willis anomalies in cerebral aneurysm rupture. J NeuroIntervent Surg. 2012;4:22–26. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2010.004358. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2010.004358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strother CM, Bender F, Deuerling-Zhengb Y, et al. Parametric color coding of digital subtraction angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:919–924. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2020. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin N, Cahill KS, Frerichs KU, et al. Treatment of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms in the USA: a paradigm shift. J Neurointervent Surg. 2012;4:182–189. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2011.004978. doi: 10.1136/jnis.2011.004978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CJ, Hung SC, Guo WY, et al. Monitoring peri-therapeutic cerebral circulation time: a feasibility study using color-coded quantitative DSA in patients with steno-occlusive arterial disease. Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1685–1690. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3049. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee KW, Tsai FY, Cheng CY. Venous hypertension may be a factor in aneurysmal rupture. A case report. Neuroradiol J. 2013;26:311–314. doi: 10.1177/197140091302600310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moscato G, Cirillo L, Dall'Olio M, et al. Management of unruptured brain aneurysms: retrospective analysis of a single centre experience. Neuroradiol J. 2013;26:315–319. doi: 10.1177/197140091302600311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin BCN, Chang FC, Tsai FY, et al. Stenotic transverse sinus predispose to poststenting hyperperfusion syndrome as evidenced by quantitative analysis of peritherapeutic cerebral circulation time. Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:1132–1136. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3838. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]