Abstract

The urinary, psychosocial, organ-specific, infection, neurological/systemic and tenderness (UPOINT) phenotype system has been validated to be an effective phenotype system in classifying patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) in western populations. To validate the utility of the UPOINT system and evaluate the effect of multimodal therapy based on the UPOINT system in Chinese patients with CP/CPPS, we performed this study. Chinese patients with CP/CPPS were prospectively offered multimodal therapy using the UPOINT system and re-examined after 6 months. A minimum 6-point drop in National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptoms Index (NIH-CPSI) was set to be the primary endpoint. Finally, 140 patients were enrolled in the study. The percentage of patients with each domain was 59.3%, 45.0%, 49.3%, 22.1%, 37.9%, and 56.4% for the UPOINT, respectively. The number of positive domains significantly correlated with symptom severity, which is measured by total NIH-CPSI scores (r = 0.796, P < 0.001). Symptom duration was associated with a greater number of positive domains (r = 0.589, P < 0.001). With 6 months follow-up at least, 75.0% (105/140) had at least a 6-point improvement in NIH-CPSI after taking the therapy. All NIH-CPSI scores were significantly improved from original ones: pain 10.14 ± 4.26 to 6.60 ± 3.39, urinary 6.29 ± 2.42 to 3.63 ± 1.52, quality of life 6.56 ± 2.44 to 4.06 ± 1.98, and total 22.99 ± 7.28 to 14.29 ± 5.70 (all P < 0.0001). Our study indicates that the UPOINT system is clinically feasible in classifying Chinese patients with CP/CPPS and directing therapy.

Keywords: chronic pelvic pain syndrome, chronic prostatitis, drug therapy, prospective study, UPOINT

INTRODUCTION

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is a common condition that significantly impacts the quality of life (Qol) of affected individuals,1 but its etiology is poorly understood.2,3 A population-based survey estimated the prevalence of CP/CPPS-like symptoms in China to be 4.5%.4 Considering the huge population of China, the actual number of patients with CP/CPPS is likely to be very large. Patients with CP/CPPS have diverse etiologies and dissimilar symptoms, and respond variable to treatment. Monotherapy has generally failed to successfully treat CP/CPPS, largely because of the heterogeneous nature of patients. Because of the clinical diversity of CP/CPPS patients, it has been suggested that individual CP/CPPS patients should be classified into a unique clinical phenotype.5 A new diagnostic/therapeutic algorithm, the urinary, psychosocial, organ-specific, infection, neurological/systemic and tenderness (UPOINT) system, was developed by Shoskes et al. in 2009 to classify patients with CP/CPPS and more importantly, to direct appropriate therapy.5 UPOINT is an acronym representing the six-domain phenotype system that the algorithm is based on, which includes urinary symptoms, psychosocial dysfunction, organ-specific findings, infection, neurological/systemic abnormalities, and tenderness of the muscles. Each domain is diagnosed clinically, linked to specific mechanisms of symptom productions or progression, and associated with specific therapies. The UPOINT system has recently been validated in several studies.6,7,8,9,10

Multimodal therapy based on the UPOINT phenotype system has been shown to greatly improve the symptoms of CP/CPPS.7 To provide international validation of the UPOINT algorithm, and to test the effects of UPOINT-based multimodal therapy, we carried out a prospective study in Chinese CP/CPPS patients. Our objectives were to assess the validity of the UPOINT phenotype system and to evaluate the efficacy of multimodal, UPOINT-based therapy in Chinese CP/CPPS patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients with CP/CPPS were prospectively evaluated in the urology Outpatient Department of Xiangya Hospital by one urologist (LLF) from January 2012 to June 2013. All were diagnosed according to National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria.11 The inclusion criteria for study participation were: (1) no major systemic illnesses, (2) complete information available on their Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (CPSI) scores and UPOINT phenotype, (3) patient agreement to adhere to the treatment plan, and (4) follow-up period of at least 6 months after the first appointment. Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria or were lost to follow-up were excluded from the study. Patient assessment included careful collection of the medical history focusing on symptoms, a digital rectal examination of the prostate and the pelvic floor muscles, physical examination, cultures of urine, premassage and postmassage urine analysis and expressed prostatic secretions. In addition, each patient was specifically questioned about their psychosocial condition; for example, whether they were experiencing stress, depression or catastrophizing (hopelessness, helplessness). Symptom severity was measured using the NIH-CPSI and reported as a total score (0–43 points), as well as subscores for pain (0–21 points), urinary symptoms (0–10 points), and Qol (0–12 points). Based on their total CPSI scores, patients were classified as having mild (0–15 points), moderate (16–29 points), or severe (>29 points) symptoms.6

To decide which UPOINT domains were positive in each patient, we adopted the criteria described by Shoskes et al.6 In brief, the urinary domain was positive if the patient had high postvoid residual urine volume, bothersome urgency, frequency, nocturia. The psychosocial domain was positive if the patient had clinical depression, catastrophizing (helplessness, hopelessness), or poor social interaction. The organ-specific domain was considered positive if there was specific prostate tenderness on examination, leukocytosis in the prostatic fluid, hematospermia, or an extensive prostatic calcification. The infection domain was positive (in the absence of recurrent or previous urinary tract infection) if Gram-negative bacilli or Enterococcus was localized to the prostatic fluid, or the urine was positive for Ureaplasma or Chlamydia, or the patient had previously responded well to antibiotic treatment. The neurological/systemic domain was positive if the patient felt pain out of the abdomen and the pelvis, or had a current diagnosis of fibromyalgia, irritable bowel disease, or chronic fatigue syndrome. Finally, the tenderness domain was considered to be positive if there were palpable spasms or trigger points in the abdomen or pelvic floor.

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Xiangya Hospital. All patients gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. A minimum 6-point reduction in the total NIH-CPSI score was the primary endpoint.7

Patients were offered therapy based on their UPOINT phenotype. For the urinary domain, patients were treated with tolterodine (8 patients), tamsulosin (72 patients), or both (3 patients), based on the severity of their symptoms and their response to previous treatment.12 For the psychosocial domain, patients who wanted treatment for depression were referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist (13 of 63 patients). For the organ-specific domain, patients were treated with cernilton tablets (74 mg bid; 69 patients).13 For the infection domain, patients were treated with culture-specific antibiotics (4 patients), or in the evidence of Ureaplasma or Chlamydia, with clarithromycin (500 mg bid for 10 days; 27 patients).7 Patients who were positive for the neurological/systemic domain were treated with amitriptyline starting at 10 mg per day and increasing to 50 mg d−1 as needed (39 patients) or with 300–3600 mg d−1 gabapentin as needed (14 patients).14,15 For muscle tenderness, patients received biofeedback therapy (79 patients).16

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, we presented our data as means ± standard deviations and counts or frequencies with percentages or proportions for categorical variables. Correlation between the number of positive domains and symptoms severity was assessed by Spearman's coefficient of rank correlation. Analysis of variance was used for comparison between multiple groups. The nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparison of categorical variables. Before and after differences in NIH-CPSI total scores were analyzed with paired t-test. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05. In the study, data were performed with SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Patient clinical presentation

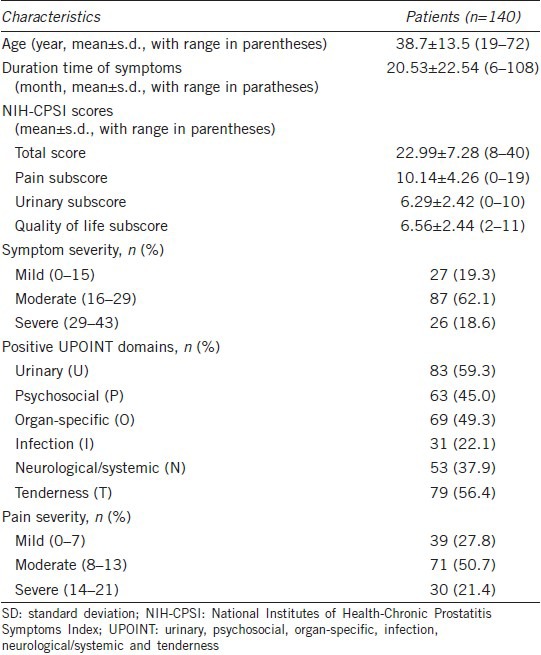

One hundred and sixty-six patients were enrolled in the study, and 26 of these were lost to follow-up. Thus, 140 patients had complete follow-up data. Patient demographic information and clinical data are shown in Table 1. The mean patient age was 38 years (range 19–72) and the mean symptom duration prior to their initial medical visit was 20 months (range 6–108). The percentages of patients with 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 positive UPOINT domains were 9.3% (13/140), 37.1% (52/140), 36.4% (51/140), 10.7% (15/140), 4.3% (6/140), and 2.1% (3/140), respectively. All patients had at least 1 positive domain, and the majority of patients had either 2 or 3 positive domains.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of the patient cohort

Validation of the urinary, psychosocial, organ-specific, infection, neurological/systemic and tenderness phenotype system

In order to validate the original findings of Shoskes et al.6 we calculated the correlations between the number of positive domains and the NIH-CPSI pain, urinary, and Qol subscores, as well as the total NIH-CPSI scores, in patients with CP/CPPS. The number of positive domains significantly correlated with the total NIH-CPSI score (Spearman r = 0.796, P < 0.001). The number of positive domains also correlated with the NIH-CPSI pain subscore (Spearman r = 0.681, P < 0.001), urinary subscore (Spearman r = 0.492, P < 0.001), and Qol subscore (Spearman r = 0.726, P < 0.001). The total NIH-CPSI score increased with the number of positive domains (from a mean score of 11.85 ± 3.16 for patients with 1 positive domain to a mean score of 36.11 ± 2.71 for those with 5 and 6 positive domains; P < 0.001, analysis of variance). Besides, symptom duration time had a strong correlation with the number of positive domains (Spearman r = 0.589, P < 0.001). Patients were considered to have mild, moderate, or severe symptoms according to their NIH-CPSI scores. The number of positive domains increased with symptom severity, the mean numbers of positive domains for patients classified as having mild, moderate, and severe symptoms were 1.70 ± 0.67, 2.54 ± 0.61, and 4.27 ± 0.92, respectively (P < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis test).

Result of multimodal therapy based on the urinary, psychosocial, organ-specific, infection, neurological/systemic and tenderness system

Twenty-nine patients received only one treatment. Of the patients that received multimodal therapy, 52, 46, 9, 3, and 1 patients received 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 types of treatment, respectively. Only a few of the patients with a positive psychosocial domain decided to seek treatment from a psychologist or psychiatrist; for this reason, the number of patients who were treated for symptoms in each of the various domains does not match the number of patients who demonstrated abnormalities in these domains. One hundred and five patients (75.0%) reached the primary endpoint of a 6-point or more reduction in their total NIH-CPSI score. The total NIH-CPSI scores of 34 patients (24.3%) were improved by ≥50% with treatment, while 112 patients (80.0%) had a 25% or more reduction in NIH-CPSI score. Overall, the mean total NIH-CPSI scores were decreased from 22.99 ± 7.28 to 14.29 ± 5.70 (P < 0.0001, by paired t-test). All NIH-CPSI subscores were also significantly improved with treatment; the mean pain subscore went from 10.14 ± 4.26 to 6.60 ± 3.39, the mean urinary subscore went from 6.29 ± 2.42 to 3.63 ± 1.52, and the mean Qol subscore went from 6.56 ± 2.44 to 4.06 ± 1.98 (all P < 0.0001, by paired t-test).

DISCUSSION

Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is a common condition that significantly impacts the Qol of affected individuals.1 However, effective treatment of patients with CP/CPPS remains difficult for urologists. Numerous treatment studies have yielded negative or conflicting results;17,18,19,20 for example, whereas many studies have shown that alpha-blockers can improve the voiding symptoms of CPPS, a well-designed, properly powered study found no difference between alfuzosin and placebo treatment in patients with CP/CPPS.12,19 Thus, many patients spend considerable amounts of money on medications, but their symptoms remain unresolved.21 It has become clear that CP/CPPS patients are a heterogeneous group with dissimilar symptoms caused by diverse etiologies, and their response to therapy is highly variable. Thus, it has been suggested that each CP/CPPS patient should be classified according to their unique clinical phenotype.5 The UPOINT clinical phenotype system was developed by Shoskes et al. in 2009 and has been recently evaluated and validated in American, Chinese, and European patients with CP/CPPS.6,7,8,9,10 Multimodal therapy based on the patient's UPOINT phenotype has been reported to achieve excellent long-term results.7 Our results further support the findings of these previous studies; we found that the UPOINT algorithm was clinically valid in Chinese CP/CPPS patients and that UPOINT-based multimodal treatment resulted in significant symptom improvement. As has been reported in previous studies,6,7,8,9,10 most of the patients in our study could be stratified into symptom domains using standard clinical criteria, and the number of positive domains significantly correlated with symptom severity as measured by NIH-CPSI scores. A step-wise increase was found in the NIH-CPSI total score, pain subscore, urinary subscore and Qol subscore as the number of positive domains increased. In accordance with the results of previous studies evaluating the UPOINT system in American and Chinese patients with CP/CPPS, we found that the duration of the symptoms was strongly correlated with the number of positive domains.6,8 This supports the hypothesis that ongoing local tissue injury and inflammation can cause local muscle spasm, central and peripheral neurological changes (allodynia, hyperalgesia), and psychosocial changes that can maintain the clinical symptoms even years after the initiating injury has resolved.22

The mean age of the patients in our cohort was 38 years, which is younger than the mean ages of the patients in several American and European studies, which ranged from 43.5 to 46.4 years.6,7,9,10 The cause of this difference requires further investigation. Despite the difference in the mean age of patients, the prevalence and the distribution of positive domains in the patients in our study were similar to those described in the American, European and Chinese studies published previously.6,7,8,9,10 Furthermore, the distribution of the patients into mild, moderate and severe categories was similar to that reported in another study of Chinese CP/CPPS patients.8 The NIH-CPSI scores (including all subscores) of our patients were also similar to previously reported scores.6,7,8,9,10 This consistency of results between different patient populations confirms the usefulness and reliability of the UPOINT clinical phenotype system. Our results further validate the utility of the UPOINT algorithm for classifying Chinese patients with CP/CPPS.

More importantly, our study demonstrated that 75% (105 of 140) of patients experienced significant improvement (a minimum 6-point decrease in total NIH-CPSI score) after at least 6 months of UPOINT-directed, multimodal therapy. Although this result was not as good as that seen in an American study, in which 84% of patients experienced a 6-point or more reduction in total NIH-CPSI score after multimodal therapy,6 when compared with the results of monotherapy for the treatment of CP/CPPS multimodal, UPOINT-directed treatment is more effective. Previous reports have shown that 70.6% of patients treated with cernilton had a 6-point or more improvement in NIH-CPSI scores after 12 weeks of treatment, 67% of patients taking quercetin had a minimum 25% improvement in NIH-CPSI scores after 4 weeks of treatment, and 44% of patients treated with finasteride had at least moderate improvement at 6 months.18,23 In the chronic prostatitis collaborative research network study of 488 men with CPPS, only 17% of patients who were treated with local therapy were significantly improved after 1 year of treatment.24

Patients with a positive psychosocial domain were not given anti-depressant drugs or benzodiazepines, but were offered referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist. However, only 20.6% (13 of 63) of the patients identified as having a positive psychosocial domain went to a psychologist or psychiatrist for treatment for depression. The results of a survey of 656 Chinese urologists in 2008 indicated that psychotherapy is not performed adequately without involvement of a psychologist or psychiatrist (29.2%), and that urologists lack experience and techniques for treatment of psychosocial symptoms (18.5%).25 Traditionally, the Chinese have considered persons with symptoms of mental disorders as mad or insane. Therefore, the patients themselves are ashamed of their symptoms and fear being seen as mad. This fear of losing “face,” which is valued by Chinese people, plays an important role in stopping patients from seeing a psychologists or psychiatrist.26 In an American cohort, 27% of patients (10 of 37) with a positive psychosocial domain had their psychosocial problem treated.7 When using UPOINT-based, multimodal therapy to treat patients with CP/CPPS, it is important to encourage patients who are identified with a positive psychosocial domain to seek help from a psychologist or psychiatrist. Collaboration between urologists and psychologists may help patients with CP/CPPS resolve their symptoms.

This study had several limitations that may have influenced the results. As patients at a tertiary referral center, our study participants had typically experienced symptoms of longer duration and greater severity than patients who might have been seen at a primary or secondary care center. This may have influenced our results through regression to the mean. In addition, dosage of individual drugs was not standard, and individual patients have diverse responses to drugs and other types of therapies. Furthermore, the positive and negative interactions of the drugs were not individually examined. Finally, as this was a nonblinded study we did not control for the placebo effect, which could have increased response rate.

Some studies have shown that adding an erectile domain to the UPOINT system improves the correlation with symptom severity,8,9 while others suggest it does not.27 Since the validity of adding an erectile domain to the UPOINT system is debatable, we did not include it in this study. The UPOINT system itself may need improvement and the criteria for each individual domain have not been fully validated;10 however, our results indicate that the UPOINT system as a whole is an effective diagnostic and treatment algorithm.

CONCLUSIONS

The utility of the UPOINT clinical phenotype system as a diagnostic and treatment-planning tool has been validated in Chinese patients with CP/CPPS. The number of positive domains was significantly correlated with the duration and severity of symptoms. Multimodal therapy based on the UPOINT clinical phenotype system yielded good medium-term results in Chinese CP/CPPS patients. Despite some limitations, this system is a promising approach to the treatment of CP/CPPS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LFL conceived of the study, participated in the data collection and helped to draft the manuscript. XG performed the statistical analysis, participated in the data collection and helped to draft the manuscript. CZ, ZYO, LW, FZ participated in the data collection and helped to draft the manuscript. LQ, ZYT, JGD participated in its design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Freedom Explore Program of Central South University (2011QNZT136) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81200549).

REFERENCES

- 1.McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Santanna J, et al. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:656–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shoskes DA, Hakim L, Ghoniem G, Jackson CL. Long-term results of multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2003;169:1406–10. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000055549.95490.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartoletti R, Cai T, Mondaini N, Dinelli N, Pinzi N, et al. Prevalence, incidence estimation, risk factors and characterization of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in urological hospital outpatients in Italy: results of a multicenter case-control observational study. J Urol. 2007;178:2411–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang CZ, Li HJ, Wang ZP, Xing JP, Hu WL, et al. The prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in China. J Urol. 2009;182:558–63. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Rackley RR, Pontari MA. Clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:177–83. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Dolinga R, Prots D. Clinical phenotyping of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and correlation with symptom severity. Urology. 2009;73:538–42. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Kattan MW. Phenotypically directed multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study using UPOINT. Urology. 2010;75:1249–53. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Z, Zhang J, He J, Zeng G. Clinical utility of the UPOINT phenotype system in Chinese males with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS): a prospective study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e52044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magri V, Wagenlehner F, Perletti G, Schneider S, Marras E, et al. Use of the UPOINT chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome classification in European patient cohorts: sexual function domain improves correlations. J Urol. 2010;184:2339–45. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hedelin HH. Evaluation of a modification of the UPOINT clinical phenotype system for the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43:373–6. doi: 10.3109/00365590903164514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Jr, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nickel JC. Role of alpha1-blockers in chronic prostatitis syndromes. BJU Int. 2008;101(Suppl 3):11–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rugendorff EW, Weidner W, Ebeling L, Buck AC. Results of treatment with pollen extract (Cernilton N) in chronic prostatitis and prostatodynia. Br J Urol. 1993;71:433–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb15988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pranikoff K, Constantino G. The use of amitriptyline in patients with urinary frequency and pain. Urology. 1998;51:179–81. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Backonja M, Glanzman RL. Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Ther. 2003;25:81–104. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ye ZQ, Cai D, Lan RZ, Du GH, Yuan XY, et al. Biofeedback therapy for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:155–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickel JC, Johnston B, Downey J, Barkin J, Pommerville P, et al. Pentosan polysulfate therapy for chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (chronic pelvic pain syndrome category IIIA): a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Urology. 2000;56:413–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00685-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nickel JC, Downey J, Pontari MA, Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI. A randomized placebo-controlled multicentre study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of finasteride for male chronic pelvic pain syndrome (category IIIA chronic nonbacterial prostatitis) BJU Int. 2004;93:991–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickel JC, Krieger JN, McNaughton-Collins M, Anderson RU, Pontari M, et al. Alfuzosin and symptoms of chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2663–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehik A, Alas P, Nickel JC, Sarpola A, Helström PJ. Alfuzosin treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Urology. 2003;62:425–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calhoun EA, McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O’Leary M, Leiby BE, et al. The economic impact of chronic prostatitis. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1231–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.11.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontari MA, Ruggieri MR. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:S61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagenlehner FM, Schneider H, Ludwig M, Schnitker J, Brahler E. A pollen extract (Cernilton) in patients with inflammatory chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a multicentre, randomised, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Eur Urol. 2009;56:544–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ, Alexander RB, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of men with chronic prostatitis: the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis cohort study. J Urol. 2002;168:593–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Liu L, Xie HW, Ginsberg DA. Chinese urologists’ practice patterns of diagnosing and treating chronic prostatitis: a questionnaire survey. Urology. 2008;72:548–51. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian M, Smith CW, Chen Z, Xia G. Psychotherapy in China: a review of its history and contemporary directions. Int J Ment Health. 2002;30:49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samplaski MK, Shoskes DA. Inclusion of an erectile dysfunction domain to the UPOINT phenotype does not improve correlation with symptom severity in a North American cohort of men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Eur Urol. 2011;(Suppl 10):194–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]