Abstract

Prostate cancer is now becoming an emerging health priority in East Asia. Most of our current knowledge on Prostate cancer has been generated from studies conducted in Western population; however, there is considerable heterogeneity of Prostate cancer between East and West. In this article, we reviewed epidemiologic trends, risk factors, disease characteristics and management of Prostate cancer in East Asian population over the last decade. Growing evidence from East Asia suggests an important role of genetic and environmental risk factors interactions in the carcinogenesis of Prostate cancer. Exposure to westernized diet and life style and improvement in health care in combination contribute substantially to the increasing epidemic in this region. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines in East Asia are largely based on Western knowledge. Although there is a remarkable improvement in the outcome over the last decade, ample evidence suggests an inneglectable difference in diagnostic accuracy, treatment efficacy and adverse events between different populations. The knowledge from western countries should be calibrated in the Asian setting to provide a better race-based treatment approach. In this review, we intend to reveal the evolving trend of Prostate cancer in the last decade, in order to gain evidence to improve Prostate cancer prevention and control in East Asia.

Keywords: Asians, diagnosis, epidemiology, genetics, prostate cancer, treatment outcome

INTRODUCTION

In the last decade, East Asia has undergone tremendous economic growth and culture globalization, which results in increasing life expectancy, changing in dietary pattern and westernized lifestyle. Once considered a disease commonly diagnosed in western countries, prostate cancer is now becoming an emerging health priority in East Asia. Because East Asia remains the world's most populous region, the number of individuals with Prostate cancer will increase substantially in the coming decades.

Most of our current knowledge on Prostate cancer has been generated from studies conducted in Western population. Since there is considerable heterogeneity of prostate cancer between East and West, new evidence is strongly needed to improve Prostate cancer prevention and control in East Asia. In this article, we reviewed epidemiologic trends, risk factors, disease characteristics, and management of Prostate cancer in East Asian population over the last decade.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

East Asia account for 23.6% of the male population worldwide and 8.2% of the male are aged 65 years or older.1 In East Asia, Japan, Taiwan region, South Korea belong to high human development area, while China belong to medium human development area.2

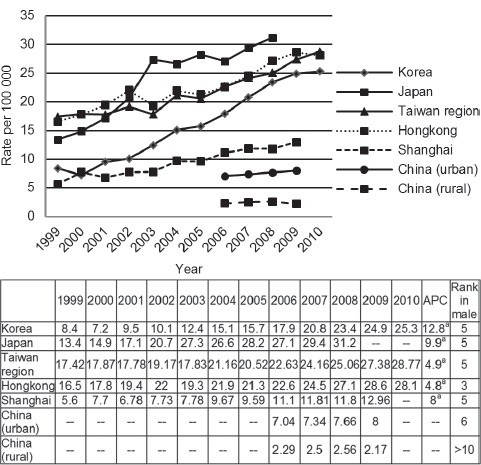

Prostate cancer is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in males worldwide, accounting for 14% of the total new cancer cases in 2008.3 About 9% (82 691) were diagnosed within the East Asia (8.2/100 000).4 Japan account for 47%, followed by China (41%) and Korean (8%). Incidence rates (IRs) varied by almost 10-fold across this region, ranging from estimates of 2.56/100 000 in rural China up to 31.2/100 000 in Japan.5,6,7,8,9,10 Except for rural China, Prostate cancer incidence increased steadily over the last decade in other East Asia area (Figure 1). The changing trend was most significantly in Korea, with an annual percentage change of 12.8. Prostate cancer was ranked as the fifth most common cancer and also the most common genitourinary cancer in developed areas such as Korea, Japan, Taiwan region and Shanghai. The increase of incidence can’t be simply attributed to more spread use of screen. The exposure rates of population based prostate specific antigen (PSA) screen have been still at around 10% in a recent Japanese report,11 which was significantly lower than the data of United States (70%–80%).12 Furthermore, the prostate biopsy rate of East Asian men was relatively low, only 54.2% and 64.3% for PSA in 4–10 and >10 ng ml−1 in a Korean nationwide survey study.13

Figure 1.

Prostate cancer standardized incidence in East Asian areas from 1999 to 2010. APC: annual percentage change. aindicates statistical significant results.

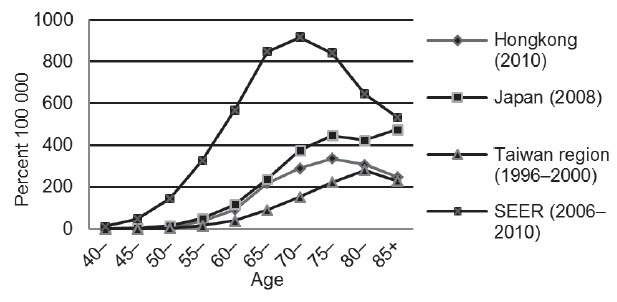

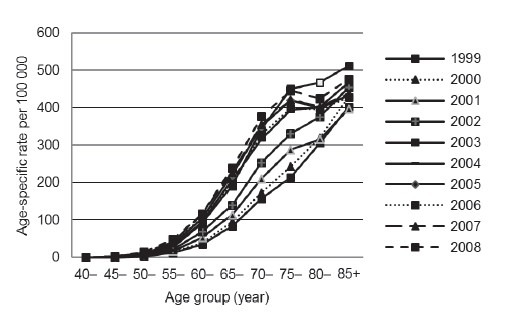

In Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan regions, a sharply increased incidence of Prostate cancer was observed after 60 years old. The distribution of age was different from patients in United States, where the increased incidence began with 50 years old (Figure 2).14 The changing pattern of age distribution of Prostate cancer in Japan over the last decade was also examined. A general increase was observed without significant shift to the young age (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Age-specific incidence of prostate cancer in East Asian areas and United States. SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program.

Figure 3.

Changing trend of prostate cancer age-specific incidence in Japan from 1999 to 2008.

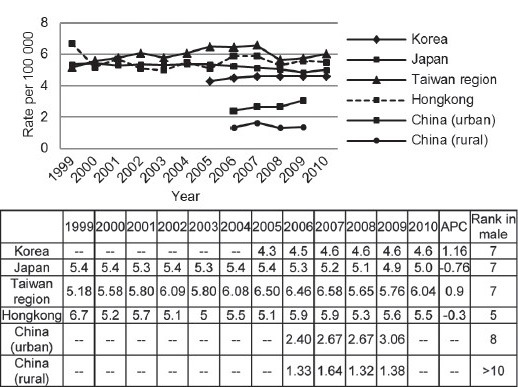

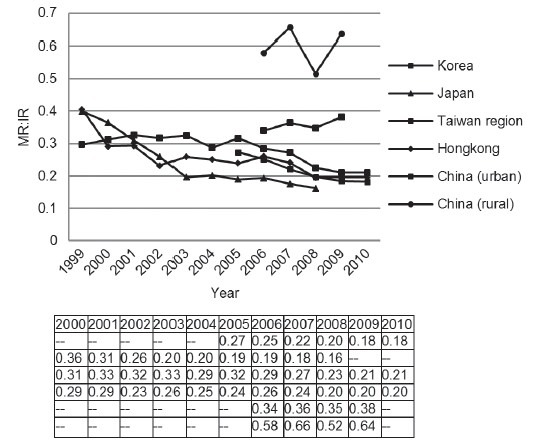

In 2008, 10% (26 751) of patients died of Prostate cancer were located in East Asia (2.5/100 000).4 China account for 53%, followed by Japan (37%) and Korea (5%). There was less variation in the age-standardized mortality rate (MR) for Prostate cancer, with highest in Taiwan region and 4 times greater than in rural China (Figure 4).5,7,8,10,15 Prostate cancer was ranked as the seventh most common cause of cancer-related deaths in a developed area as Korea, Japan and Chinese Taiwan region. For the trend of mortality, we found most of area shares a similar plateau pattern. Specifically, a significant decrease of mortality was observed in Japan.

Figure 4.

Prostate cancer standardized mortality in East Asian areas from 1999 to 2010.

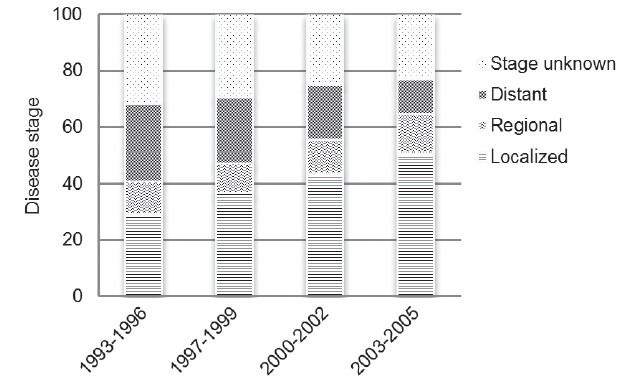

Regarding Prostate cancer survival, we evaluated the ratio of MR: IR. Over the last decade, a general decrease of the MR: IR value was observed in developed area. On the other hand, the value was approximately 0.6 in rural China, nearly 3 times over developed area (Figure 5). These data were consistent with reported 5-year survival rate from different areas. The latest survival rate was over 90% in Korea and Japan, comparable to the data in United States.5,14,16 However, disease survival rate was only 36.1% in Shanghai between 1992 and 1995.11 Stage migration may substantially account for improvement in disease outcome. In Japan, the proportion of localized disease improved dramatically from 30% to nearly 50% (Figure 6).16 On the contrary, 68% of newly diagnosed Chinese patients had metastatic disease in a recent multicenter study.17

Figure 5.

Prostate cancer MR: IR (MR divide IR) in East Asian areas from 1999 to 2010. MR: mortality ratio; IR: incidence ratio.

Figure 6.

Distribution of disease stage of prostate cancer in Japan from 1993 to 2005.

RISK FACTORS

The carcinogenesis of Prostate cancer is a complex interplay between genetics and environment exposure. Observed differences between race groups may be reflective of not only the differences in genetic structure or function, but also disparity in common environmental exposure, diet, lifestyle, and attitudes toward health care. One example is that Asian American had much higher of Prostate cancer incidence than their ancestry.18 Although the improvement of health care including cancer screen account for some increase in Prostate cancer incidence, they can hardly interpret all increase according to the epidemiology data above mentioned. Therefore, we discuss possible risk factors, which fasten the increase of Prostate cancer in East Asia.

Diet plays a major role in Prostate cancer carcinogenesis and biology. In Western countries, diet tends to be high in animal products and fine processed, while in Eastern countries, the diet is relatively lower in calories and is more likely to contain greater amounts of certain essential nutrients.19 Many epidemiological studies showed that increased fat and meat intake is associated with Prostate cancer risk,20 most studies (including one study from China, of which the odds ratio was 3.321) found positive associations (odds ratio [OR] ≥1.3) between total fat intake and the risk of Prostate cancer while slightly fewer failed to find this relation. The data on meat and Prostate cancer are more consistent than those on fat, 16 of the 22 studies reviewed showed a risk ratio of 1.3 or more,20 of which included one study from Japan (OR = 2).22

Tea, a traditional drink in East Asia, is found to have a protective effect for Prostate cancer. Zheng et al.23 indicated that green tea may have a protective effect on prostate through a meta-analysis, the summary odd ratio of Prostate cancer indicated a borderline significant association in Asian populations for highest green tea consumption versus non/lowest (OR = 0.62). The protective capacity of green tea is also confirmed by Japanese studies,24 the multivariate relative risk was 0.52 for men drinking five or more cups/day compared with <1 cup per day. Soybean, as another traditional food in East Asia, also has anti Prostate cancer affect. A meta-analysis including eight epidemiological studies showed that soybean intake can reduce the prevalence of Prostate cancer for more than 30%.25 It is said that soybeans are a rich source of isoflavones, a main type of plant estrogens, which have been suggested to modulate endogenous hormone homeostasis or hormone metabolism.26,27

There are less interethnic differences in risk of Prostate cancer if diet is similar between different ethnics. Whittemore et al.28 conducted a multi-ethnic research in populations mainly from the US, and indicated that a positive statistically significant association of Prostate cancer risk and total fat intake was found for all ethnic groups combined (Blacks, Whites, Asian-Americans). Interestingly, for Asian-Americans, the author found that saturated fat intake was associated with higher risks for Asian-Americans than for Blacks and Whites.

Physical activity has shown to be linked to a significantly decreased risk of breast and colorectal cancer in numerous studies, in Prostate cancer the evidence was weaker but still probable in a Poland study.29 A study from Malaysia indicated that the past history of not engaging in any physical activities at the age of 45–54 years old increased risk of Prostate cancer by approximately three folds (adjusted OR 2.9 [95% confidence interval = 0.8–10.8]) (P < 0.05).30 However, a study for Asian-Americans didn’t support the linkage.28 Limitations of these results exists that the methods are various in the assessment of physical activity, including its frequency, duration and intensity.31

The change of diet and lifestyle inevitably resulted in obesity. The increased prevalence of obesity was evidenced in East Asia.32 Using WHO criteria, the percentage of overweight men in Japan, Korea, and China are 30.1%, 34.3%, and 25.5% in 2008. Furthermore, raised cholesterol was found in 57%, 42.2%, and 31.8%, respectively. The rising trend of metabolism disorders may be responsible for increasing trend of Prostate cancer in East Asia.

GENETICS

Over the last decade, breakthrough improvement in sequencing techniques provides better understanding of the role of genetic alterations in the etiology of Prostate cancer. Therefore, the hypothesis whether Prostate cancer is different in East Asian population was tested by genetic evaluation. Better knowledge of genetic changes open the door of personalized medicine covering prevention, screening and management.

Germline variations

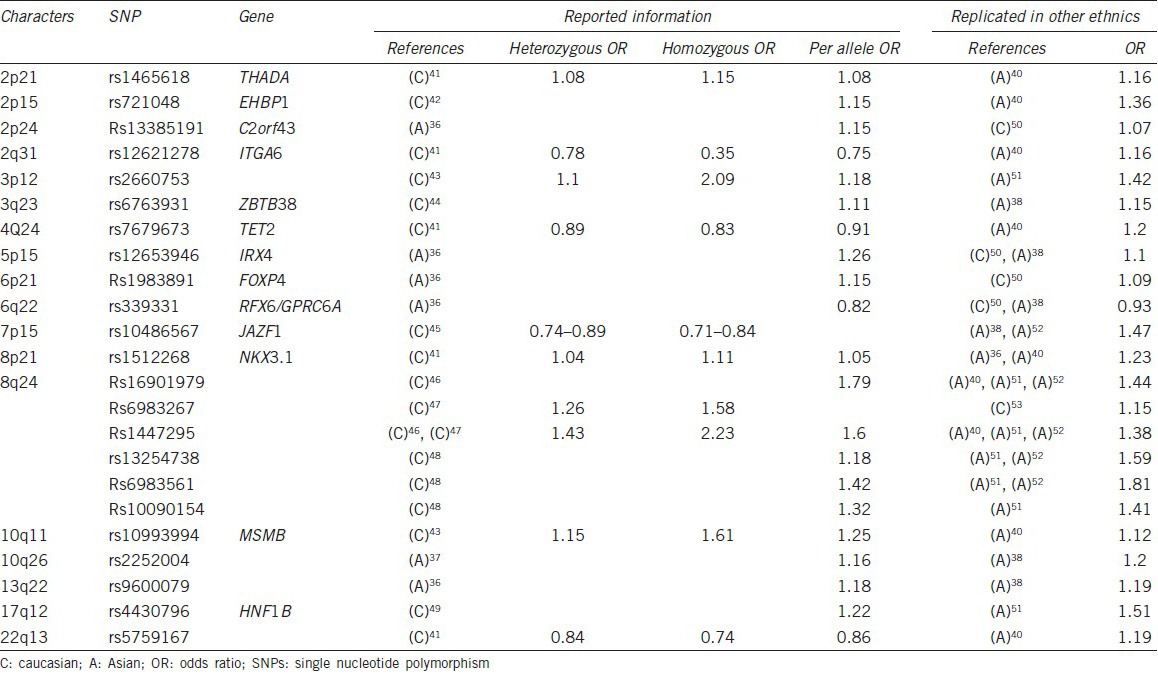

Genetic factors play important roles in Prostate cancer etiology and that genetic research can help clarify Prostate cancer susceptibility. Until now, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on several 1000 samples of several ethnic groups had identified more than 70 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on various genes or chromosomal loci that are associated with Prostate cancer susceptibility. Most of the GWAS were performed in European populations, while three GWAS were performed in Asian descent with two from Japanese33,34 and one from Chinese.35 New SNPs were found by Asian GWAS suggesting that SNP genotype frequencies may vary by race and partially account for racial differences in Prostate cancer risk. In addition, multiple researchers have aimed to replicate GWAS results identified from European descent in populations of Asians and provided evidence of ethnic differences and similarity in genetic susceptibility to Prostate cancer.36,37 As shown in Table 1, more than 20 SNPs were confirmed to have homogeneous characteristics in both ethnics.33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50 Interestingly, some of those SNPs were proved to have genetic functions associated with carcinogenesis.

Table 1.

SNPs which showed homogeneous characteristics in different ethnics

Metabolism

Nearly all SNPs identified from GWAS studies, which were known to be linked with metabolism related genes, were successfully replicated and showed Prostate cancer risk association in Asian populations. Those SNPs included rs1465618 from 2p21 (THADA),35 rs339331 from 6q22 (GPRC6A),33,47 rs10486567 from 7p15 (JAZF1),35,49 rs7501939, rs4430796 and rs11649743 from 17q12 (HNF1B).48

Inflammatory

Rs1983891, a loci related with Prostate cancer risk identified by a Japanese GWAS was replicated by an American research.47 Rs1983891 was located in intron 2 of FOXP4 (forkhead box P4), which is expressed in both thymocytes and peripheral CD4 (+) and CD8 (+) T-cells and is necessary for normal T-cell cytokine recall responses to antigen following pathogenic infection.51

Recently, GWAS on Chinese Prostate cancer patients identified a new susceptibility locus rs103294 at 19q13, which is linked with LILRA3. LILRA3 is a gene regulating inflammatory response, and was significantly associated with the messenger ribonucleic acid expression of LILRA3 in T-cells.35 It remains unknown whether this loci is also associated with Prostate cancer susceptibility in European populations because no replication studies were published yet. However, Spanish and Polish studies indicated its association with multiple sclerosis,52,53 indicating LILRA3 is responsible for immunity defects not only in Chinese patients.

Prostate specific single nucleotide polymorphisms

Prostate specific genes are usually associated with prostate carcinogenesis as well as prostate susceptibility. Most of their related SNPs were replicated both in European populations and Asian populations, showing homogeneous characteristics. Of which, three were successfully replicated in Asian populations and showed an association with Prostate cancer risk, including rs12653946 from 5p15 (IRX4),33,54,55 rs1512268 from 8p21 (NKX3.1)37,42 and rs10993994 from 10q11 (MSMB).37,49

8q24

The 8q24 region was the first to show its association with Prostate cancer risk,56 subsequent GWAS studies have further identified the importance of 8q24 as a region of susceptibility to Prostate cancer.42,43,44,45,57,58,59 SNPs of this region were also responsible for increased risk for other cancer types.60,61 Despite that this region contains various independent Prostate cancer-susceptibility loci within a 1Mb segment; it appears to have little transcriptional activity.

Some other positively confirmed SNPs were associated with Prostate cancer risk in both Eastern and Western countries. Those included function unidentified SNPs such as rs2660753 from 3p1248 and rs5759167 from 22q13,37 as well as gene specific SNPs such as rs721048 from 2p15 (EHBP1),37 rs13385191 from 2p24 (C2orf43),47 rs12621278 from 2q31 (ITGA6),62 rs6763931 from 3q23 (ZBTB38),35 rs7679673 from 4q24 (TET2) etc.37

Somatic variations

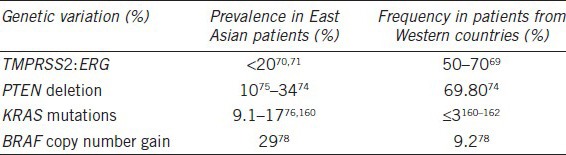

In addition to the aforementioned SNPs associated with Prostate cancer susceptibility, a variety of genetic and epigenetic alterations have been found to be involved in Prostate cancer initiation, progression, metastasis and drug resistance (Table 2).

Table 2.

The prevalence of genetic events for prostate carcinogenesis among different ethnic groups

The most common known genetic alteration in Prostate cancer is a fusion of TMPRSS2: ERG. The fusion involve the 5’ untranslated region of the androgen-regulated gene TMPRSS2 and members of the ETS transcription factor family, ERG or ETV.63,64 The presence of these gene fusions is essentially 100% specific for Prostate cancer, and can be detected in as many as 50%–70% of Prostate cancer samples. The TMPRSS2: ERG gene fusion have been causally linked to cancer progression because it promotes invasion, and over expression of the fusion product in mice shows great enhanced Prostate cancer development.65 The prevalence of the TMPRSS2: ERG fusion in Prostate cancer appears to vary in different ethnic groups. It was reported that in Caucasians the frequencies were 50%–70%,66 while in Asian patients the frequencies were lower than 20%.67,68

Another common known gene of interest is PTEN. Deletions in PTEN are observed in over 60% of Prostate cancers, and in 20%–25% of HGPIN lesions. The loss of inhibition of pathway downstream of PTEN may be important in cancer, including AKT and mammalian target of rapamycin.69 It was reported that loss or alteration of PTEN allele is correlated with disease progression to the metastatic stage.70 Mao et al.71 compared PTEN deletion/inactivation frequency among Chinese and UK patients. In this article, he revealed that low-level (− or +) expression of PTEN was detected in 69.8% (111/159) of UK samples, but only in 34% (31/91) of Chinese samples. In Japanese, loss of heterozygosity at the PTEN locus was observed in 11.1% of Prostate cancers.72

RAS-RAF-MAPK pathway mutants were much more frequently found in Asian patients than patients from western countries.73,74 It is unknown if genetic factors or environmental factors cause the difference in RAS mutation rates among different ethnic groups, although the latter seems more likely. A similar difference in the frequency of BRAF mutation was also found in both ethnics.75 These results indicate that the RAS-RAF-MAPK signaling pathway may be essential for prostate susceptibility for Asian men.

DIAGNOSIS

Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment of cancer. The introduction of PSA screen in the mid-1980s increased Prostate cancer IR drastically in United States, at about 12%/year, and peaked in 1992. The rate subsequently declined, at about 10%/year for the following 3 years and then appeared to stabilize from 1995 to 2005.76,77 Simultaneously, the incidence of distant disease decreased to 2.9%,78 much lower than it is in China (68%).17 Since a substantial part of men in East Asian are diagnosed at an advanced stage, massive screening such as PSA screen of Prostate cancer is suggested by physicians. Therefore, the diagnostic performance of PSA and other innovative markers should be evaluated before widely used.

The general cut-off for prostate biopsy was a total PSA of 4 ng ml−1. In western countries this threshold is associated with risks of Prostate cancer ranging from 15% to 40%.79 One research enrolling 16222 Chinese patients tried to find out the PSA levels of Chinese men. They discovered that the PSA level of Chinese men who are under 60 years is lower than that of Caucasians, while the PSA level of Chinese men who are above 60 years is higher than that of Caucasians, which means for patients above 60 the PSA cut-off should be higher than usual for Chinese men.80 Na et al.81 observed only 4.7% of men with a PSA level of 4 ng ml−1 were diagnosed with Prostate cancer, much lower than rates in western countries. In another study in ethnic Chinese, the PSA test sensitivity at the traditional cut-off (4.0ng ml−1) was 96% (specificity = 14%) and if a cutoff of 6.0 ng ml−1 is used the sensitivity will be 90% together with a higher specificity (36%). Thus, the author suggests among the population with low incidence of Prostate cancer as Chinese, minimizing unnecessary biopsies might be more important issue than maximizing cancer detection rate.82

Various adjustments, such as the ratio of free-to-total (f/t) PSA, PSA density or PSA velocity were attempted to improve the diagnostic value of PSA. The most common PSA derivative is the ratio of free PSA to total PSA, and the recommend cut-off is 0.14–0.16 in some Asian countries.83,84 However, the effects of PSA derivatives are affected by differences in prostate volume. Lam et al.85 reported that at similar levels of total PSA, PSA density may be higher in Hispanic than in Caucasian. In Asia, patients may also have smaller prostate volumes compared to whites, resulting in a higher PSA level per unit volume. Results showed that PSA density in Asian was a significantly better predictor of Prostate cancer than f/tPSA.86,87

Diagnostic procedures apart from serum PSA-related testing are also of great interest, for this can greatly ignore the heterogeneity of cancer development. Cao et al.88 established a multiplex model including urine PCA3, TMPRSS2: ERG, Annexin A3 and sarcosine to predict Prostate cancer in Chinese patients and got favorable results. He mentioned that further validation experiments and optimization for the strategy of constructing this model are warranted.

TREATMENT

Be aware of the rising threat of Prostate cancer, physicians in East Asia work together to establish the best treatment strategies for their patients. Over the last decade, regional guideline regarding management of Prostate cancer was published by medical associations.89 Although standardized treatment remarkably improve the implementation of state-of-art knowledge in East Asia, most of evidence are gain from Western countries and are used under the hypothesis that a similar outcome will be replicated in Asians. Fortunately, more and more studies published form Asian physicians investigate the hypothesis and discussed whether we should adapt other than adopt the western approach. Hereby, we followed the nature history of Prostate cancer, discussed the treatment across early to advanced disease.

Active surveillance

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment are considered a common scene in screen detected Prostate cancer. To overcome the drawbacks, active surveillance has been evolving as a management strategy for indolent tumors. Unfortunately, the selection criteria of active surveillance, especially in Asian populations, still remain to be standardized.90,91,92,93 One study from Korea suggested that 30.5% (40/131) of patients who meet all the conditions of the contemporary Epstein criteria for prediction of clinically insignificant Prostate cancer might actually harbor Prostate cancer with unfavorable pathological features (Gleason score ≥7 and/or extraprostatic extension) and such an underestimation rate of tumor grade by the Epstein criteria is relatively high compared with data from Western countries.90,94,95 Other cohorts also concluded there was a difference in incidence of about 13%–16% between populations according to the results of Asian and Western studies using each of the same AS protocols.90,93,96 Since similar observation was found in African American, these results indicated different carcinogenesis pathway may possible affect tumor characteristics. For example cancer in the anterior prostate is quite difficult to detect using current biopsy techniques. Thus a more accurate and balanced active surveillance protocol for Asian cohorts is needed. Recently, data derived from Asia demonstrated that the statistical model (nomogram) and the measurement of the diameter of suspicious tumor lesions on diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging could improve the prediction of insignificant Prostate cancer in candidates for active surveillance.97,98 Therefore, these tools might be helpful in guiding urologists’ selection of the proper active surveillance candidates.

Radiation therapy

External beam radiation therapy

In Japan, one of the most developed countries in Asia, the use of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is gaining acceptance as a first-line treatment for Prostate cancer. Moreover, patient characteristics and treatment characteristics are becoming more similar to patients in the United States.99 In a multi-institutional study of EBRT for Prostate cancer in Japan, the 5-year overall, clinical progression-free, and biochemical relapse-free survival rate were 93.0%, 95.3%, and 71.9% for all patients. The 5-year progression-free, and biochemical relapse-free survival rates according to the risk group were 100%, 90.8% in the low-risk group, 98.3%, 75.7% in the intermediate-risk group and 93.6%, 67.6% in the high-risk group.100 The author also mentioned that the survival result is comparable to T1-T2 patients who had a radical prostatectomy in Japan,101 indicating that EBRT is a promising option in low and intermediate risk patients in Asia. However, consensus has not been reached on the practice and management of postoperative RT for patients with Prostate cancer in Japan yet.102 In a study of EBRT for intermediate and advanced Prostate cancer in China, the 5-year survival was 79.5%,103 a bit higher than 71.4% from a Europe randomized trial.104 Unfortunately, little solid data of EBRT for Prostate cancer from other Asian countries can be reached.

Brachytherapy

Permanent prostate brachytherapy using iodine-125 seeds has grown rapidly since the establishment of guidelines. In a Japanese study involving 663 patients with low-risk and low-tier intermediate-risk confined disease, The 7-year cause-specific survival and overall survival (OS) were 99.1% and 96.4% and there were no significant difference between different risk groups.105 In addition, the result was excellent compared to data from other studies (5-year biochemical disease-free survival-rates = 81% from Austria,106 10-year biochemical disease-free survival rate was 83% for Caucasians107). On the other hand, brachytherapy for high-risk Asian patients also had favorable results.108,109

Radical prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is the major curative treatment for men with localized Prostate cancer and is the only one that has been proven to show a benefit for OS and cancer-specific survival compared with conservative management in a prospective randomized trial.110 Recently, robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RARP) has been developed and the shift toward RARP has reshaped the surgical approach for localized Prostate cancer. Several recent reports compared the outcomes of RARP with open RP or laparoscopic RP and suggested that RARP might be noninferior in terms of oncological outcomes and might be superior in functional outcomes with a lower or equal rate of complications.111,112,113,114 Although the use of RARP in East Asia has been somewhat delayed and less widespread compared with Western counties due to the obstacles in financial reimbursement, patient volume and surgical skill development, the outlook for RARP in East Asia remains rosy.115,116 Future robotic systems (da Vinci S models) with a smaller footprint, leaner instrument arms and lower costs would better serve many Asian patients.

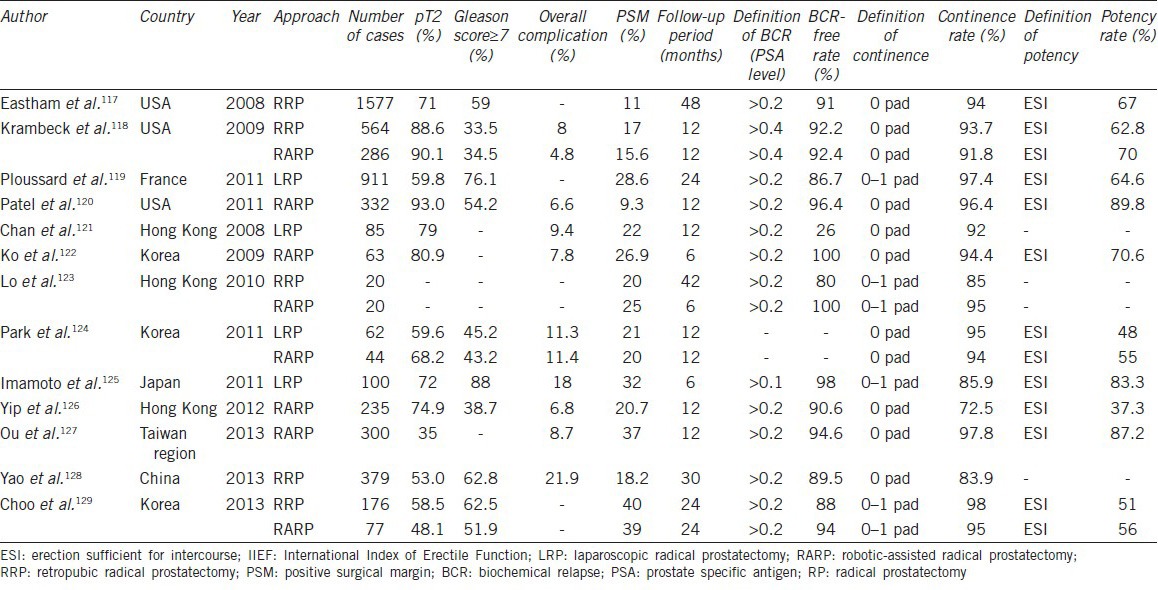

We reviewed the current literatures117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129 and compared perioperative parameters and the trifecta outcomes (cancer control, continence, and potency) following RP among Asians and Westerners (Table 3). As the improvement of the technical expertise and the migration toward low-risk disease in recent years, the perioperative complication rate and oncological outcomes has been comparable in the series from East Asia and Western countries. However, it is reported that the potency recovery following RP is inferior in Asian populations.130,131,132,133,134,135 Namiki et al.130 prospectively compare the recovery of sexual function and bother during the first 2 years after RP between American and Japanese men and found that Japanese men had a smaller improvement in sexual function and bother over time than did the American men postoperatively after adjusting for baseline score, age, baseline PSA and nerve-sparing. That is to say, American men were more likely to regain their baseline sexual function by 24 months after surgery (hazard ratio [HR] =1.60) and were less likely to return to baseline sexual bother (HR = 0.57) than Japanese men. The cultural differences may contribute to the different patterns of recovery of sexual function between Asian and Western patients after RP. Furthermore, the fact that in many parts of Asia the PSA screening is not common and the proportion of pT3-4 tumor is high, which result in less use of nerve-sparing techniques, may play a certain role in the discrepancy.

Table 3.

Comparison of perioperative parameters and the trifecta outcome following RP among Asians and Westerners

Androgen deprivation therapy

Currently, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is widely used as primary treatment for advanced Prostate cancer and as adjuvant treatment for locally advanced Prostate cancer. The influence of race on the effectiveness of ADT has aroused some scholar's interest due to the incidence of Prostate cancer vary widely in different races. Fukagai et al.136 compared the outcomes of Caucasian men (CM) and Japanese-American men (JAM) treated with ADT and reported that JAM showed a much better outcome than CM in terms of overall and cause-specific survival rate (P = 0.001 and 0.036, respectively). Moreover, they found that race was one of the significant prognostic factors in the multivariate analysis (P = 0.03). Soon afterwards, Fukagai et al.137 investigated the clinical outcome after ADT among Chinese, Filipino, JAM and CM and reported that Chinese men show almost the same prognosis as JAM and better prognosis than CM while Filipinos show a worse prognosis after ADT than JAM but a better prognosis than CM. These data indicated that ADT is more effective in Asians. Lately, Fujimoto et al.138 reported that active androgen transport SLCO2B1 genotype (GG allele), which occurred more frequently in African and Caucasian populations than in Japanese and Han Chinese population, is associated with the shorter time to progression in patients who received ADT. Therefore, the germline genetic function alterations underlying ADT efficacy warrant further evaluation to answer the discrepancy in outcome.

It is likely that not only sensitivity of Prostate cancer to ADT but also side effects of ADT differ among racial groups. Studies from Japan139,140 indicated the low prevalence of osteoporosis in both hormone-naïve and ADT-treated Japanese Prostate cancer patients, even in patients treated with ADT for more than 2 years, which are quite different from studies examining patients in Western counties.141,142 In addition, data for the general population show that the incidence of ischemic heart disease is much lower in Japanese than in Westerners. For bone fractures, as well, the incidence is much lower in Japanese than in Westerners.143 The fact that overall rates of cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome at baseline in Asian populations were lower might be associated with the less frequency of ADT-related side effects.144,145,146 Therefore, it should be interesting to explore possible protect factors underlying race difference.

Chemotherapy

Although the effectiveness of ADT has been confirmed for advanced Prostate cancer, in virtually all patients, the disease inevitably advances to the androgen-independent stage within a median of 18–24 months after castration.147 To such relapsed Prostate cancer after primary ADT failure, chemotherapy could be used as the standard treatment. Currently, docetaxel combined with prednisone is still used as the standard first-line chemotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) patients due to the survival benefit as well as palliative benefit in the TAX 327 and Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 99–16 studies.148,149 However, the reports on the efficacy of docetaxel-based chemotherapy mainly included patients from Western countries and studies from Asia are relatively limited. A study in Korean men showed that the PSA response of 51% and median OS of 22.8 months are comparable to or even better than those from TAX 327 study, which revealed the PSA response rate of 45% and median OS of 19.2 months.148,150,151 Also, in the Korean study,150 the time to PSA progression (5.8 months) is comparable to time to progression reported in SWOG 99–16 study (6.3 months) and the clinicopathologic characteristics of Korean patients, with the exception of the fact that more Korean patients with a Gleason score ≥8, were quite similar to those of the TAX 327 and SWOG 99–16 studies.

As cancer treatment goals shift from mere improvement in OS to maintaining better quality of life, attention should be paid to chemotherapy-related toxic effects. In TAX 327 and SWOG 99–16 studies, the most common Grade 3 or 4 adverse events associated with docetaxel or mitoxantrone chemotherapy were nausea/vomiting, neutropenia, alopecia, cardiovascular events, infection, pain, diarrhea, nail changes, sensory neuropathy, and anorexia.148,149 Results from East Asia revealed that the docetaxel-based chemotherapy was clinically feasible for Asian patients with metastatic CRPC and the main adverse events were neutropenia, leukopenia, febrile neutropenia, asthenia, anorexia and neuropathy.150,152,153,154,155 It is reported that febrile neutropenia occurred much more frequently (13%) in Korean patients with metastatic CRPC treated with docetaxel (75 mg m−2 every 3 weeks) than those of phase III studies or systemic review incorporating Western patients (3%–6%).148,149,150,156 Previously, Naito et al.153 have reported that the incidence of febrile neutropenia was as high as 16% in Japanese patients with CRPC treated with lower docetaxel (70 mg m−2 every 3 weeks). It is possible that the observed differences in clinical toxicity to docetaxel between Asian and Western patients may be related to the docetaxel pharmacokinetic differences and that the diversity of polymorphisms in CYP3A isoenzymes in patients from different racial backgrounds may contribute to these differences.157,158 Moreover, the liver function impairment, which is common in East Asia, especially in China, is associated with the development of severe docetaxel-induced side-effects.159 Therefore, caution should be exercised when treating Asian patients with docetaxel-based chemotherapy, especially with respect to the development of febrile neutropenia in patients of older age, or with poor performance status.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer epidemic in East Asia is characterized by rapid rates of increase over the last decade. Exposure to westernized diet and life style and improvement in health care in combination contribute substantially to the increasing epidemic in this region. Growing evidence from East Asia suggests an important role of genetic and environmental risk factors interactions in the carcinogenesis of Prostate cancer. Further research of secular trends and risk factors is strongly needed to prevent the disease in the area with a huge population.

Diagnostic and treatment guidelines in East Asia are largely based on Western knowledge. Although there is a remarkable improvement in the outcome over the last decade, ample evidence suggests an inneglectable difference in diagnostic accuracy, treatment efficacy and adverse events. The knowledge from western countries should be calibrated in the Asian setting to provide a better race-based treatment approach. For the next decades, translational research investigating underlying disparities in East Asia Prostate cancer subjects is felt with highest needs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YZ carried out the epidemiology part of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. HKW worked on risk factors, genetics, diagnosis and part of treatment and outcome section. YYQ worked on treatment and outcome. DWY conceived of the study and participated in its design and coordination.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81001131) and The 973 National Science and technology projects (No. 2012CB518300).

REFERENCES

- 1.United States Census Bureau, International Data Base 2008. 2008. web link: http://www.census.gov/population/international/data/idb/informationGateway.php .

- 2.Human Development Report, United Nations Development Programme, 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, et al. GLOBOCAN 2008 v2.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10. Internet. web link: http://globocan.iarc.fr/

- 5.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 2013;45:1–14. doi: 10.4143/crt.2013.45.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda A, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katanoda K, Sobue T, et al. Cancer incidence and incidence rates in Japan in 2007: a study of 21 population-based cancer registries for the Monitoring of Cancer Incidence in Japan (MCIJ) project. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:328–36. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghiringhelli F, Vincent J, Guiu B, Chauffert B, Ladoire S. Bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI-3 in chemotherapy-refractory patients with metastatic colorectal cancer in the era of biotherapies. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30:758–64. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9575-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyato H, Kitayama J, Hidemura A, Ishigami H, Kaisaki S, et al. Vagus nerve preservation selectively restores visceral fat volume in patients with early gastric cancer who underwent gastrectomy. J Surg Res. 2012;173:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute SC. Shanghai Cancer Incidence Data. web link: http://www.tumorsci.org/html/list_646.html .

- 10.Zhao P. Military Medical Scientific publishers; 2009-2012. Chinese Cancer Registry Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao CX, Xiang YB, Liu ZW, Gao J, Sun L, et al. The analysis of the relative survival for urological cancer in urban Shanghai. Chin J Clin Oncol. 2005;32:321–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sirovich BE, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Screening men for prostate and colorectal cancer in the United States: does practice reflect the evidence? JAMA. 2003;289:1414–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.11.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung MS, Lee SH, Lee DH, Kim SJ, Kim CS, et al. Practice patterns of Korean urologists for screening and managing prostate cancer according to PSA level. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:1136–41. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.6.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang HW, Kim D, Kim HJ, Kim CH, Kim YS, et al. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance as risk factors for colorectal adenoma: a cross-sectional, case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:178–87. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Roermund JG, Bol GH, Witjes JA, Ruud Bosch JL, Kiemeney LA, et al. Periprostatic fat measured on computed tomography as a marker for prostate cancer aggressiveness. World J Urol. 2010;28:699–704. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0497-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuda T, Ajiki W, Marugame T, Ioka A, Tsukuma H, et al. Population-based survival of cancer patients diagnosed between 1993 and 1999 in Japan: a chronological and international comparative study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:40–51. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma CG, Ye DW, Li CL, Zhou FJ, Yao XD, et al. [Epidemiology of prostate cancer from three centers and analysis of the first-line hormonal therapy for the advanced disease] Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;46:921–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez SL, Noone AM, Lichtensztajn DY, Scoppa S, Gibson JT, et al. Cancer incidence trends among Asian American populations in the United States, 1990-2008. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1096–110. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori S, Butler E, McLoughlin J. Prostate cancer and diet: food for thought? BJU Int. 2011;107:1348–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolonel LN. Fat, meat, and prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23:72–81. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MM, Wang RT, Hsing AW, Gu FL, Wang T, et al. Case-control study of diet and prostate cancer in China. Cancer Causes Control. 1998;9:545–52. doi: 10.1023/a:1008840105531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishina T, Watanabe H, Araki H, Nakao M. Epidemiological study of prostatic cancer by matched-pair analysis. Prostate. 1985;6:423–36. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990060411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J, Yang B, Huang T, Yu Y, Yang J, et al. Green tea and black tea consumption and prostate cancer risk: an exploratory meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63:663–72. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2011.570895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurahashi N, Sasazuki S, Iwasaki M, Inoue M, Tsugane S, et al. Green tea consumption and prostate cancer risk in Japanese men: a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:71–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Meta-analysis of soy food and risk of prostate cancer in men. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:667–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park JW, Choi YJ, Suh SI, Kwon TK. Involvement of ERK and protein tyrosine phosphatase signaling pathways in EGCG-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in Raw 264.7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;286:721–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mäkelä S, Poutanen M, Kostian ML, Lehtimäki N, Strauss L, et al. Inhibition of 17beta-hydroxysteroid oxidoreductase by flavonoids in breast and prostate cancer cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:310–6. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whittemore AS, Kolonel LN, Wu AH, John EM, Gallagher RP, et al. Prostate cancer in relation to diet, physical activity, and body size in blacks, whites, and Asians in the United States and Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:652–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.9.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kruk J, Aboul-Enein HY. Physical activity in the prevention of cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahar S, Shafurah S, Hasan Shaari NS, Rajikan R, Rajab NF, et al. Roles of diet, lifetime physical activity and oxidative DNA damage in the occurrence of prostate cancer among men in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:605–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Bae J, Nam BH, Yoo KY. Aetiology of cancer in Asia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:371–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles 2011; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takata R, Akamatsu S, Kubo M, Takahashi A, Hosono N, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new susceptibility loci for prostate cancer in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2010;42:751–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akamatsu S, Takata R, Haiman CA, Takahashi A, Inoue T, et al. Common variants at 11q12, 10q26 and 3p11.2 are associated with prostate cancer susceptibility in Japanese. Nat Genet. 2012;44:426–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.1104. S1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J, Mo Z, Ye D, Wang M, Liu F, et al. Genome-wide association study in Chinese men identifies two new prostate cancer risk loci at 9q31.2 and 19q13. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1231–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng J, Liu F, Lin X, Wang X, Ding Q, et al. Predictive performance of prostate cancer risk in Chinese men using 33 reported prostate cancer risk-associated SNPs. Prostate. 2012;72:577–83. doi: 10.1002/pros.21462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Hsing AW, Wang X, Shao Q, Qi J, et al. Systematic confirmation study of reported prostate cancer risk-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms in Chinese men. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1916–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Al Olama AA, Giles GG, Guy M, et al. Identification of seven new prostate cancer susceptibility loci through a genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1116–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Bergthorsson JT, Manolescu A, et al. Common sequence variants on 2p15 and Xp11.22 confer susceptibility to prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:281–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Olama AA, Guy M, et al. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:316–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kote-Jarai Z, Olama AA, Giles GG, Severi G, Schleutker J, et al. Seven prostate cancer susceptibility loci identified by a multi-stage genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2011;43:785–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Kraft P, Wacholder S, et al. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:310–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Manolescu A, Amundadottir LT, Gudbjartsson D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:631–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeager M, Orr N, Hayes RB, Jacobs KB, Kraft P, et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:645–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haiman CA, Patterson N, Freedman ML, Myers SR, Pike MC, et al. Multiple regions within 8q24 independently affect risk for prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:638–44. doi: 10.1038/ng2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Steinthorsdottir V, Bergthorsson JT, Thorleifsson G, et al. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:977–83. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindström S, Schumacher FR, Campa D, Albanes D, Andriole G, et al. Replication of five prostate cancer loci identified in an Asian population – results from the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:212–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0870-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada H, Penney KL, Takahashi H, Katoh T, Yamano Y, et al. Replication of prostate cancer risk loci in a Japanese case-control association study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1330–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng SL, Hsing AW, Sun J, Chu LW, Yu K, et al. Association of 17 prostate cancer susceptibility loci with prostate cancer risk in Chinese men. Prostate. 2010;70:425–32. doi: 10.1002/pros.21076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Troutman SM, Sissung TM, Cropp CD, Venzon DJ, Spencer SD, et al. Racial disparities in the association between variants on 8q24 and prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2012;17:312–20. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiehagen KR, Corbo-Rodgers E, Li S, Staub ES, Hunter CA, et al. Foxp4 is dispensable for T cell development, but required for robust recall responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ordóñez D, Sánchez AJ, Martínez-Rodríguez JE, Cisneros E, Ramil E, et al. Multiple sclerosis associates with LILRA3 deletion in Spanish patients. Genes Immun. 2009;10:579–85. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wisniewski A, Wagner M, Nowak I, Bilinska M, Pokryszko-Dragan A, et al. 6.7-kbp deletion in LILRA3 (ILT6) gene is associated with later onset of the multiple sclerosis in a Polish population. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang L, McDonnell SK, Slusser JP, Hebbring SJ, Cunningham JM, et al. Two common chromosome 8q24 variants are associated with increased risk for prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2944–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Batra J, Lose F, Chambers S, Gardiner RA, Aitken J, et al. A replication study examining novel common single nucleotide polymorphisms identified through a prostate cancer genome-wide association study in a Japanese population. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1391–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Amundadottir LT, Sulem P, Gudmundsson J, Helgason A, Baker A, et al. A common variant associated with prostate cancer in European and African populations. Nat Genet. 2006;38:652–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Blondal T, Gylfason A, et al. Genome-wide association and replication studies identify four variants associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1122–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson DF, Masson G, Agnarsson BA, et al. A study based on whole-genome sequencing yields a rare variant at 8q24 associated with prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1326–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al Olama AA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Guy M, Morrison J, et al. Multiple loci on 8q24 associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1058–60. doi: 10.1038/ng.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, Pharoah PD, Thompson D, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 2007;447:1087–93. doi: 10.1038/nature05887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haiman CA, Le Marchand L, Yamamato J, Stram DO, Sheng X, et al. A common genetic risk factor for colorectal and prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:954–6. doi: 10.1038/ng2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terada N, Tsuchiya N, Ma Z, Shimizu Y, Kobayashi T, et al. Association of genetic polymorphisms at 8q24 with the risk of prostate cancer in a Japanese population. Prostate. 2008;68:1689–95. doi: 10.1002/pros.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, Dhanasekaran SM, Mehra R, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomlins SA, Mehra R, Rhodes DR, Smith LR, Roulston D, et al. TMPRSS2:ETV4 gene fusions define a third molecular subtype of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3396–400. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carver BS, Tran J, Gopalan A, Chen Z, Shaikh S, et al. Aberrant ERG expression cooperates with loss of PTEN to promote cancer progression in the prostate. Nat Genet. 2009;41:619–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rubin MA, Maher CA, Chinnaiyan AM. Common gene rearrangements in prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3659–68. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magi-Galluzzi C, Tsusuki T, Elson P, Simmerman K, LaFargue C, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prevalence and class are significantly different in prostate cancer of Caucasian, African-American and Japanese patients. Prostate. 2011;71:489–97. doi: 10.1002/pros.21265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xue L, Mao X, Ren G, Stankiewicz E, Kudahetti SC, et al. Chinese and Western prostate cancers show alternate pathogenetic pathways in association with ERG status. Am J Cancer Res. 2012;2:736–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sircar K, Yoshimoto M, Monzon FA, Koumakpayi IH, Katz RL, et al. PTEN genomic deletion is associated with p-Akt and AR signalling in poorer outcome, hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2009;218:505–13. doi: 10.1002/path.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang S, Gao J, Lei Q, Rozengurt N, Pritchard C, et al. Prostate-specific deletion of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene leads to metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:209–21. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mao X, Yu Y, Boyd LK, Ren G, Lin D, et al. Distinct genomic alterations in prostate cancers in Chinese and Western populations suggest alternative pathways of prostate carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5207–12. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Orikasa K, Fukushige S, Hoshi S, Orikasa S, Kondo K, et al. Infrequent genetic alterations of the PTEN gene in Japanese patients with sporadic prostate cancer. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:228–30. doi: 10.1007/s100380050078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen Y, Lu Y, Yin X, Zhu G, Zhu J. KRAS and BRAF mutations in prostate carcinomas of Chinese patients. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;198:35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watanabe M, Shiraishi T, Yatani R, Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN. International comparison on ras gene mutations in latent prostate carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:174–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ren G, Liu X, Mao X, Zhang Y, Stankiewicz E, et al. Identification of frequent BRAF copy number gain and alterations of RAF genes in Chinese prostate cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:1014–23. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Coyle LM, Cerhan J, Correa R, et al. Bethesda, MD, USA: National Cancer Institute, NIH; 1999. Prostate Cancer Trends 1973-1995, SEER Program; pp. 99–4543. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment after the introduction of prostate-specific antigen screening: 1986-2005. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1325–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li J, Djenaba JA, Soman A, Rim SH, Master VA. Recent trends in prostate cancer incidence by age, cancer stage, and grade, the United States, 2001-2007. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:691380. doi: 10.1155/2012/691380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, Hugosson J, Jones JS, et al. The relationship between prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer risk: the Prostate Biopsy Collaborative Group. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:4374–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guan M, Sun SL, Xie RH, Huang ZP, Wen SW, et al. [Age-specific reference ranges for prostate specific antigen in 16 222 Chinese men] Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2011;43:586–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Na R, Jiang H, Kim ST, Wu Y, Tong S, et al. Outcomes and trends of prostate biopsy for prostate cancer in Chinese men from 2003 to 2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wu TT, Huang JK. The clinical usefulness of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level and age-specific PSA reference ranges for detecting prostate cancer in Chinese. Urol Int. 2004;72:208–11. doi: 10.1159/000077116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Amirrasouli H, Kazerouni F, Sanadizade M, Sanadizade J, Kamalian N, et al. Accurate cut-off point for free to total prostate-specific antigen ratio used to improve differentiation of prostate cancer from benign prostate hyperplasia in Iranian population. Urol J. 2010;7:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang Y, Sun G, Pan JG, Guo ZJ, Li T. Performance of tPSA and f/tPSA for prostate cancer in Chinese. a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2006;9:374–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lam JS, Cheung YK, Benson MC, Goluboff ET. Comparison of the predictive accuracy of serum prostate specific antigen levels and prostate specific antigen density in the detection of prostate cancer in Hispanic-American and white men. J Urol. 2003;170:451–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000074707.49775.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sakai I, Harada K, Hara I, Eto H, Miyake H. Limited usefulness of the free-to-total prostate-specific antigen ratio for the diagnosis and staging of prostate cancer in Japanese men. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9:64–7. doi: 10.1007/s10147-003-0365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zheng XY, Xie LP, Wang YY, Ding W, Yang K, et al. The use of prostate specific antigen (PSA) density in detecting prostate cancer in Chinese men with PSA levels of 4-10 ng/mL. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134:1207–10. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cao DL, Ye DW, Zhang HL, Zhu Y, Wang YX, et al. A multiplex model of combining gene-based, protein-based, and metabolite-based with positive and negative markers in urine for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:700–10. doi: 10.1002/pros.21286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kamidono S, Ohshima S, Hirao Y, Suzuki K, Arai Y, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice Guidelines for Prostate Cancer (Summary-JUA 2006 Edition) Int J Urol. 2008;15:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee SE, Kim DS, Lee WK, Park HZ, Lee CJ, et al. Application of the Epstein criteria for prediction of clinically insignificant prostate cancer in Korean men. BJU Int. 2010;105:1526–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kakehi Y, Kamoto T, Shiraishi T, Ogawa O, Suzukamo Y, et al. Prospective evaluation of selection criteria for active surveillance in Japanese patients with stage T1cN0M0 prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:122–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sugimoto M, Shiraishi T, Tsunemori H, Demura T, Saito Y, et al. Pathological findings at radical prostatectomy in Japanese prospective active surveillance cohort. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:973–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee DH, Jung HB, Lee SH, Rha KH, Choi YD, et al. Comparison of pathological outcomes of active surveillance candidates who underwent radical prostatectomy using contemporary protocols at a high-volume Korean center. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42:1079–85. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bastian PJ, Mangold LA, Epstein JI, Partin AW. Characteristics of insignificant clinical T1c prostate tumors. A contemporary analysis. Cancer. 2004;101:2001–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jeldres C, Suardi N, Walz J, Hutterer GC, Ahyai S, et al. Validation of the contemporary epstein criteria for insignificant prostate cancer in European men. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1306–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yeom CD, Lee SH, Park KK, Park SU, Chung BH. Are clinically insignificant prostate cancers really insignificant among Korean men? Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:358–62. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chung JS, Choi HY, Song HR, Byun SS, Seo SI, et al. Nomogram to predict insignificant prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy in Korean men: a multi-center study. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:74–80. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee DH, Koo KC, Lee SH, Rha KH, Choi YD, et al. Tumor lesion diameter on diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging could help predict insignificant prostate cancer in patients eligible for active surveillance: preliminary analysis. J Urol. 2013;190:1213–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ogawa K, Nakamura K, Sasaki T, Onishi H, Koizumi M, et al. Radical external beam radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer in Japan: changing trends in the patterns of care process survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:1310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakamura K, Mizowaki T, Imada H, Karasawa K, Uno T, et al. External-beam radiotherapy for localized or locally advanced prostate cancer in Japan: a multi-institutional outcome analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:200–4. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yokomizo A, Murai M, Baba S, Ogawa O, Tsukamoto T, et al. Percentage of positive biopsy cores, preoperative prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, pT and Gleason score as predictors of PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy: a multi-institutional outcome study in Japan. BJU Int. 2006;98:549–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sasaki T, Nakamura K, Ogawa K, Onishi H, Otani Y, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy for patients with prostate cancer in Japan; Changing trends in national practice between 1996-98 and 1999-2001: patterns of care study for prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:649–54. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Luo HC, Cheng HH, Lin GS, Fu ZC, Li DS. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy combined with endocrine therapy for intermediate and advanced prostate cancer: long-term outcome of Chinese patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:4711–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.8.4711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mottet N, Peneau M, Mazeron JJ, Molinie V, Richaud P. Addition of radiotherapy to long-term androgen deprivation in locally advanced prostate cancer: an open randomised phase 3 trial. Eur Urol. 2012;62:213–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ohashi T, Yorozu A, Saito S, Momma T, Toya K, et al. Outcomes following iodine-125 prostate brachytherapy with or without neoadjuvant androgen deprivation. Radiother Oncol. 2013;109:241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Goldner G, Pötter R, Battermann JJ, Kirisits C, Schmid MP, et al. Comparison between external beam radiotherapy (70 Gy/74 Gy) and permanent interstitial brachytherapy in 890 intermediate risk prostate cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2012;103:223–7. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yamoah K, Stone N, Stock R. Impact of race on biochemical disease recurrence after prostate brachytherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:5589–600. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ohashi T, Yorozu A, Saito S, Momma T, Nishiyama T, et al. Combined brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy without adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy for high-risk prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2014;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Park DS, Gong IH, Choi DK, Hwang JH, Shin HS, et al. Outcomes of Gleason Score=8 among high risk prostate cancer treated with 125I low dose rate brachytherapy based multimodal therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2013;54:1207–13. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.5.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, Garmo H, Stark JR, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1708–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lim SK, Kim KH, Shin TY, Rha KH. Current status of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: how does it compare with other surgical approaches? Int J Urol. 2013;20:271–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ploussard G, de la Taille A, Moulin M, Vordos D, Hoznek A, et al. Comparisons of the perioperative, functional, and oncologic outcomes after robot-assisted versus pure extraperitoneal laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;65:610–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC, Artibani W, Carroll PR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:405–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ficarra V, Novara G, Ahlering TE, Costello A, Eastham JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting potency rates after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:418–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yip SKh, Sim HG. Robotic radical prostatectomy in East Asia: development, surgical results and challenges. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20:80–5. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283337bf0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ham WS, Park SY, Rha KH, Kim WT, Choi YD. Robotic radical prostatectomy for patients with locally advanced prostate cancer is feasible: results of a single-institution study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:329–32. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Eastham JA, Scardino PT, Kattan MW. Predicting an optimal outcome after radical prostatectomy: the trifecta nomogram. J Urol. 2008;179:2207–10. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Krambeck AE, DiMarco DS, Rangel LJ, Bergstralh EJ, Myers RP, et al. Radical prostatectomy for prostatic adenocarcinoma: a matched comparison of open retropubic and robot-assisted techniques. BJU Int. 2009;103:448–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ploussard G, de la Taille A, Xylinas E, Allory Y, Vordos D, et al. Prospective evaluation of combined oncological and functional outcomes after laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: trifecta rate of achieving continence, potency and cancer control at 2 years. BJU Int. 2011;107:274–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Patel VR, Sivaraman A, Coelho RF, Chauhan S, Palmer KJ, et al. Pentafecta: a new concept for reporting outcomes of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2011;59:702–7. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Chan SW, Lam KM, Kwok SC, Yu C, Au WH, et al. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: single centre experience after 5 years. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:192–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ko YH, Ban JH, Kang SH, Park HS, Lee JG, et al. Does robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy enable to obtain adequate oncological and functional outcomes during the learning curve? From the Korean experience. Asian J Androl. 2009;11:167–75. doi: 10.1038/aja.2008.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lo KL, Ng CF, Lam CN, Hou SS, To KF, et al. Short-term outcome of patients with robot-assisted versus open radical prostatectomy: for localised carcinoma of prostate. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:31–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Park JW, Won Lee H, Kim W, Jeong BC, Jeon SS, et al. Comparative assessment of a single surgeon's series of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: conventional versus robot-assisted. J Endourol. 2011;25:597–602. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Imamoto T, Goto Y, Utsumi T, Fuse M, Kawamura K, et al. Complications, urinary continence, and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: single-surgeon experience for the first 100 cases. Prostate Cancer. 2011;2011:606505. doi: 10.1155/2011/606505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Yip KH, Yee CH, Ng CF, Lam NY, Ho KL, et al. Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in Hong Kong: a review of 235 cases. J Endourol. 2012;26:258–63. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ou YC, Yang CK, Wang J, Hung SW, Cheng CL, et al. The trifecta outcome in 300 consecutive cases of robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy according to D’Amico risk criteria. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yao XD, Liu XJ, Zhang SL, Dai B, Zhang HL, et al. Perioperative complications of radical retropubic prostatectomy in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer: a comparison with clinically localized prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:241–5. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Choo MS, Choi WS, Cho SY, Ku JH, Kim HH, et al. Impact of prostate volume on oncological and functional outcomes after radical prostatectomy: robot-assisted laparoscopic versus open retropubic. Korean J Urol. 2013;54:15–21. doi: 10.4111/kju.2013.54.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Namiki S, Kwan L, Kagawa-Singer M, Tochigi T, Ioritani N, et al. Sexual function following radical prostatectomy: a prospective longitudinal study of cultural differences between Japanese and American men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2008;11:298–302. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4501013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Namiki S, Arai Y. Sexual quality of life for localized prostate cancer: a cross-cultural study between Japanese and American men. Reprod Med Biol. 2011;10:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s12522-011-0076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hong SK, Doo SH, Kim DS, Lee WK, Park HZ, et al. The 5-year functional outcomes after radical prostatectomy: a real-life experience in Korea. Asian J Androl. 2010;12:835–40. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Namiki S, Carlile RG, Namiki TS, Fukagai T, Takegami M, et al. Racial differences in sexuality profiles among American, Japanese, and Japanese American men with localized prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:2625–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Namiki S, Ishidoya S, Ito A, Kawamura S, Tochigi T, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy in Japanese men: a 5-Year follow up study. Int J Urol. 2009;16:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Namiki S, Arai Y. Health-related quality of life in men with localized prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2010;17:125–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Fukagai T, Namiki TS, Carlile RG, Yoshida H, Namiki M. Comparison of the clinical outcome after hormonal therapy for prostate cancer between Japanese and Caucasian men. BJU Int. 2006;97:1190–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Fukagai T, Namiki T, Carlile RG, Namiki M. Racial differences in clinical outcome after prostate cancer treatment. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:455–66. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Fujimoto N, Kubo T, Inatomi H, Bui HT, Shiota M, et al. Polymorphisms of the androgen transporting gene SLCO2B1 may influence the castration resistance of prostate cancer and the racial differences in response to androgen deprivation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16:336–40. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang W, Yuasa T, Tsuchiya N, Maita S, Kumazawa T, et al. Bone mineral density in Japanese prostate cancer patients under androgen-deprivation therapy. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2008;15:943–52. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yuasa T, Maita S, Tsuchiya N, Ma Z, Narita S, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density and androgen-deprivation therapy in Japanese prostate cancer patients. Urology. 2010;75:1131–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.10.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bruder JM, Ma JZ, Basler JW, Welch MD. Prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis by central and peripheral bone mineral density in men with prostate cancer during androgen-deprivation therapy. Urology. 2006;67:152–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Morote J, Morin JP, Orsola A, Abascal JM, Salvador C, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis during long-term androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69:500–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Namiki M, Ueno S, Kitagawa Y, Fukagai T, Akaza H. Effectiveness and adverse effects of hormonal therapy for prostate cancer: Japanese experience and perspective. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:451–7. doi: 10.1038/aja.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Liu L, Miura K, Fujiyoshi A, Kadota A, Miyagawa N, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States and in Japan. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:84–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Senoo K, Suzuki S, Sagara K, Otsuka T, Matsuno S, et al. Coronary artery diseases in Japanese patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Cardiol. 2014;63:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Murakoshi N, Aonuma K. Epidemiology of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in Asia. Circ J. 2013;77:2419–31. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-13-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Qu YY, Dai B, Kong YY, Ye DW, Yao XD, et al. Prognostic factors in Chinese patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:110–5. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, Lara PN, Jr, Jones JA, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Lee JL, Kim JE, Ahn JH, Lee DH, Lee J, et al. Efficacy and safety of docetaxel plus prednisolone chemotherapy for metastatic hormone-refractory prostate adenocarcinoma: single institutional study in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2010;42:12–7. doi: 10.4143/crt.2010.42.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Berthold DR, Pond GR, Soban F, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: updated survival in the TAX 327 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:242–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Shimazui T, Kawai K, Miyanaga N, Kojima T, Sekido N, et al. Three-weekly docetaxel with prednisone is feasible for Japanese patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a retrospective comparative study with weekly docetaxel alone. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:603–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Naito S, Tsukamoto T, Koga H, Harabayashi T, Sumiyoshi Y, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisolone for the treatment of metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a multicenter Phase II trial in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:365–72. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Miyake H, Sakai I, Harada K, Muramaki M, Fujisawa M. Significance of docetaxel-based chemotherapy as treatment for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in Japanese men over 75 years old. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:1697–703. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Li YF, Zhang SF, Zhang TT, Li L, Gan W, et al. Intermittent tri-weekly docetaxel plus bicalutamide in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: a single-arm prospective study using a historical control for comparison. Asian J Androl. 2013;15:773–9. doi: 10.1038/aja.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Wailoo A, Sutton A, Morgan A. The risk of febrile neutropenia in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with docetaxel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:436–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Miura N, Numata K, Kusuhara Y, Shirato A, Hashine K, et al. Docetaxel-prednisolone combination therapy for Japanese patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a single institution experience. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40:1092–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Goh BC, Lee SC, Wang LZ, Fan L, Guo JY, et al. Explaining interindividual variability of docetaxel pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in Asians through phenotyping and genotyping strategies. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3683–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Bruno R, Vivier N, Veyrat-Follet C, Montay G, Rhodes GR. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships for docetaxel. Invest New Drugs. 2001;19:163–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1010687017717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Konishi N, Hiasa Y, Tsuzuki T, Tao M, Enomoto T, et al. Comparison of ras activation in prostate carcinoma in Japanese and American men. Prostate. 1997;30:53–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970101)30:1<53::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Moyret-Lalle C, Marçais C, Jacquemier J, Moles JP, Daver A, et al. Ras, p53 and HPV status in benign and malignant prostate tumors. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:124–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Liu T, Willmore-Payne C, Layfield LJ, Holden JA. Lack of BRAF activating mutations in prostate adenocarcinoma: a study of 93 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17:121–5. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31818816b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]