(Albert Schweitzer) did not preach and did not warn and did not dream that his example would be an ideal and comfort to innumerable people. He simply acted out of inner necessity.

– Albert Einstein, friend

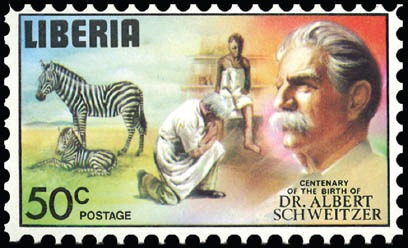

Musician, theologian and physician, Albert Schweitzer was above all, a true humanitarian. The overarching principle that guided him was ‘reverence for life’, a philosophy that took him to the jungles of Africa, where he healed many and touched the lives of millions worldwide.

MULTITALENTED

Albert Schweitzer, born on January 14, 1875 in Alsace, Germany (now a part of France), was the son of a Lutheran minister and member of a family of ministers, scholars and musicians, which included a famous cousin, Jean-Paul Sartre. As a child, Schweitzer played the organ and piano, and was only nine when he first performed at his father’s church. His musical talent earned him international recognition. Although he dedicated his life to the healing profession, he continued to perform as an organist throughout his life, even publishing a book on organ construction and a biography on Bach.

In 1893, Schweitzer enrolled at the University of Strasbourg. He received a doctorate in philosophy in 1899 and a teaching degree in theology the following year. Following in the footsteps of his father, Schweitzer became the pastor of Saint Nicholas Church in Strasbourg and worked at the Theological College of Saint Thomas for nearly a decade. During that time, he published, among other works, a scholarly text entitled The Quest of the Historical Jesus.

In 1904, Schweitzer experienced a turning point in his life after reading an article published by the Paris Missionary Society, which highlighted an urgent need for physicians in Gabon, a French colony in Africa. The article so moved him that he immediately decided to pursue a medical career, much to the disappointment of his family, colleagues and friend – the only exception being a rare woman named Helene Bresslau, whom he eventually married. A determined Schweitzer re-entered the University of Strasbourg in 1905 at the age of 30, funding his medical education with fees from concert performances and lectures. Eight years later, he graduated with specialisations in tropical medicine and surgery. Incredibly, the Paris Missionary Society initially rejected his application to join its programme in Africa, fearing that other ‘liberals and radicals’ would follow suit. However, the Schweitzers agreed to raise their own funds to cover the first two years of expenses, which caused the Paris Missionary Society to relent. In March 1913, Dr and Mrs Schweitzer left for Africa to build a hospital at Lambaréné in the French Congo, and according to historical records, the work had started in a modified chicken coop.

AFRICA

Schweitzer’s arrival in Africa was beset with challenges. Within a year, World War I broke out, and being German citizens, the Schweitzers were considered enemies of France. In 1917, they were interned as prisoners of war, first in the Pyrenees, then in a former mental institution at Saint Remy, where Vincent van Gogh was confined during his last months of life. Upon an early release, the Schweitzers returned to Europe and remained there for the next six years. During that time, Dr Schweitzer maintained his medical skills as well as his pastoral and musical interests, writing several texts, including On the Edge of the Primeval Forest, The Decay and Restoration of Civilization, Civilization and Ethics, and Christianity and the Religions of the World. Schweitzer finally returned to Lambaréné in 1924 and remained there for the rest of his life. Unfortunately, his wife Helene could not remain by his side, as she had contracted tuberculosis during their earlier stay at Lambaréné, and was not well enough to withstand the rigorous living conditions in the jungles of Africa. It was a difficult separation for the family, and Schweitzer had to make do with letters and infrequent visits. In due course, their daughter Rhena moved to Africa to work with her father and eventually took charge of the mission.

While being transported upstream on the Ogowe River from Lambaréné, Schweitzer honed his philosophy of ‘reverence for life’. He reasoned that the morality of man should extend to the entire creation of the universe and that relationships should be both deepened and widened, with each person acting in accordance with his beliefs, as he himself had done. Schweitzer also believed that all should live a portion of their lives for others. His philosophy embraced not only humans but also all living creatures, as was demonstrated by the multitude of animals that populated the hospital grounds.

GLIMPSES

Schweitzer is said to possess a hearty sense of humour, with a full-bodied laughter. He often laughed at himself and his public image, but also had a temper that expressed itself in glowering silence or bursts of verbal outrage. His colleagues and staff learned very quickly that contradicting his orders would incite his temper. Journalists who visited Schweitzer in Africa often perceived him as an aloof and didactic figure. However, those who stayed longer than a few weeks found him to be profoundly caring and deeply concerned with all life, both human and animal, and one who exercised great discipline in the running of his hospital.

One author wrote: “At Lambaréné, Schweitzer was doctor and surgeon in the hospital, pastor of a congregation, administrator of a village, superintendent of buildings and grounds, writer of scholarly books, commentator on contemporary history, musician, host to countless visitors.” However, Schweitzer was not without detractors. Although over the years the hospital at Lambaréné had grown to approximately 70 buildings capable of housing 500 patients, he was often criticised for his autocratic methods of running the hospital, the lack of updated methods of practising medicine, the unsanitary conditions of the hospital, the menagerie of animals allowed to roam freely on the hospital grounds, and the primitive conditions at Lambaréné.

AN ENDURING LEGACY

For his medical and humanitarian works, Schweitzer won many awards, including honorary doctorates, the Goethe Prize of Frankfurt, and the Order of Merit, Britain’s highest civilian honour. Dr Schweitzer also won the Nobel Peace Prize, which was bestowed upon him on December 10, 1953. Predictably, he used the $33,000 monetary award to fund the addition of a leprosy wing at his hospital.

Over the course of his mission in Lambaréné, Schweitzer’s fame grew, attracting volunteers, admirers and journalists, all of whom he welcomed to witness his beliefs in action. He was fond of saying that “my life is my argument”. The symbolic significance of Albert Schweitzer, the man of Lambaréné, inspired the founding of clinics, orphanages and hospitals throughout the world, in particular the Cameroons, Haiti, France, South America, and Tom Dooley’s legendary hospital in Laos. In his book, Albert Schweitzer’s Mission: Healing and Peace, Norman Cousins wrote: “… Schweitzer’s main achievement was a simple one. He was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for a moral principle. Like Gandhi, the power of his appeal was in renunciation. And because he was able to feel a supreme identification with other human beings he exerted a greater force than armed men on the march… It suffices that his words and works are known and that he is loved and has influence because he enabled men to discover mercy in themselves … He reached countless millions who never saw him but who were able to identify themselves with him because of the invisible and splendid fact of his own identification with them.”

Albert Schweitzer died on September 4, 1965, at the age of 90, in his modest quarters at Lambaréné, and was buried on the banks of the Ogowe River, a simple self-made cross marking his grave. Today, his hospital at Lambaréné continues to serve the needs of the people of the region.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- •.Anderson E. New York: Harper & Row; 1964. Albert Schweitzer’s Gift of Friendship. [Google Scholar]

- •.Albert Schweitzer – Biographical. Nobelprize.org [online] [Accessed February 5 2008]. Available at: http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1952/schweitzer-bio.html .

- •.Albert Schweitzer International Albert Schweitzer Association. [Accessed February 6 2008]. Available at: http://www.schweitzer.org/

- •.Albert Schweitzer. International Network on Personal Meaning. 1874-1965. [Accessed February 6 2008]. Available at: http://www.meaning.ca/living/worthy_lives/WLschweitzer.htm .

- •.Brabazon J. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press; 2000. Albert Schweitzer: A Biography. [Google Scholar]

- •.Cousins N. New York: WW Norton & Company; 1985. Albert Schweitzer’s Mission: Healing and Peace. [Google Scholar]

- •.Schweitzer A. Memoirs of Childhood and Youth. In: Bergel, Kurt, Bergel, Alice R, translators. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]