Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a chronic, degenerative, and significant cause of visual impairment and blindness in the elderly. Genetic and epidemiological studies have confirmed that AMD has a strong genetic component, which has encouraged the application of increasingly sophisticated genetic techniques to uncover the important underlying genetic variants. Although various genes and pathways have been implicated in the risk for AMD, complement activation has been emphasized repeatedly throughout the literature as having a major role both physiologically and genetically in susceptibility to and pathogenesis of this disease. This article explores the research efforts that brought about the discovery and characterization of the role of inflammatory and immune processes (specifically complement) in AMD. The focus herein is on the genetic evidence for the role of complement in AMD as supported specifically by genome-wide association (GWA) studies, which interrogate hundreds of thousands of variants across the genome in a hypothesis-free approach, and other genetic interrogation methods.

The two major genetic contributors to age-related macular degeneration (AMD) are variants in the CFH (complement factor H) and ARMS2/HTRA1 genes. Genetic studies have identified additional complement genes associated with AMD.

The complement system is a key mediator of three central physiologic activities including host defense against infection, waste disposal, and the overlap between innate and adaptive immunity (Walport 2001a). The more than 40 proteins and regulators that comprise this system are found in the systemic circulation (Khandhadia et al. 2012). There are three complement pathways, each with a unique activator. The classical pathway is triggered by an antibody–antigen complex, the alternative pathway is activated by host cell or pathogen surface binding, and the lectin pathway is triggered by surface polysaccharides of microbes (Khandhadia et al. 2012). For an extensive review of the complement system, the reader is referred to other published reviews (Morgan 1995; Hageman et al. 2001; Walport 2001a,b; Anderson et al. 2002). Disorders of the complement system have been implicated in numerous diseases including atypical hemolytic uremia, systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome, multiple autoimmune diseases, and age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Degn et al. 2011). We focus herein on the role of genetic mediators in the complement system implicated in AMD.

Although the current understanding of AMD etiology is far from complete, research has established that it is a heterogeneous disease with early and late stages and multiple subtypes. Early AMD is defined by the presence of drusen, visible on ophthalmoscopy as focal yellow deposits of acellular, polymorphous debris, along with focal hyperpigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and pathologic alterations to the RPE and Bruch’s membrane (reviewed in Miller 2013; Ratnapriya and Chew 2013). Progression from early to late AMD varies between patients (Klein and Klein 2007; Tikellis et al. 2007), although the underlying reasons for this variation have not yet been elucidated. Advanced AMD is characterized by choroidal neovascularization, geographic atrophy, or both. Neovascular or “wet” AMD is distinguishable by formation and leakage of new blood vessels under or within the retina. Nonneovascular “dry” AMD is characterized by progressive RPE and outer retinal atrophy. Both forms can lead to irreversible vision loss, and current clinical management lacks the promise of full visual restoration. Current treatment for neovascular AMD consists of intraocular injections of antiangiogenic agents that target vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a secreted endothelial mitogen that is the key regulator of angiogenesis and vascular permeability and has been implicated as an important factor in development and progression of neovascular AMD (reviewed in Ratnapriya and Chew 2013). There is currently limited therapy for nonneovascular AMD.

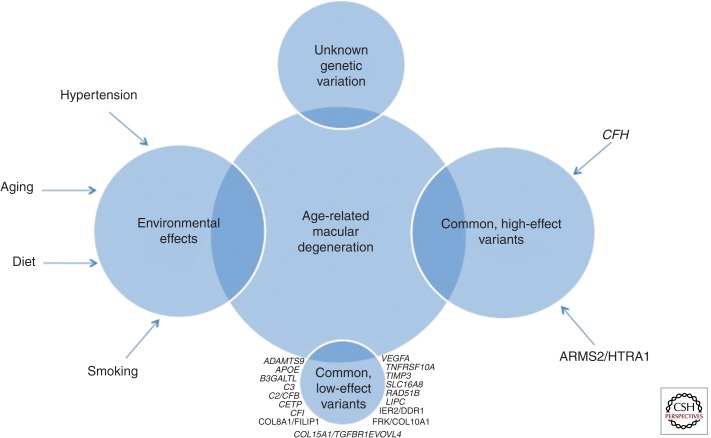

AMD susceptibility and pathogenesis are influenced by multiple factors, as highlighted in Fig. 1, including genetic polymorphisms, environmental factors, and interactions between them (reviewed in DeAngelis et al. 2011). The undisputable contribution of genetic variation to AMD is supported by several lines of evidence including increased risk for AMD among relatives of patients (Klaver et al. 1998; Clemons et al. 2005; Swaroop et al. 2007) and twin studies reporting higher rates in monozygotic versus dizygotic twin pairs (Klein et al. 1994; Meyers 1994; Meyers et al. 1995; Klaver et al. 1998; Hammond et al. 2002). Extensive genetic studies of AMD, including genome-wide linkage screens, candidate gene studies, and genome-wide association (GWA) studies, have identified multiple variants that alter AMD risk (e.g., Weeks et al. 2000, 2001, 2004; Majewski et al. 2003; Schick et al. 2003; Seddon et al. 2003; Iyengar et al. 2004; Fisher et al. 2005). Major risk-modifying loci include variants in the CFH gene on chromosome 1 (e.g., Edwards et al. 2005; Hageman et al. 2005; Haines et al. 2005; Klein et al. 2005; Souied et al. 2005; Zareparsi et al. 2005; Baird et al. 2006; Conley et al. 2006; Hughes et al. 2006) and the ARMS2-HTRA1 locus on chromosome 10 (e.g., Jakobsdottir et al. 2005; Rivera et al. 2005; Maller et al. 2006; Schmidt et al. 2006; Yang et al. 2006; Shuler Jr. et al. 2007; Fritsche et al. 2008). Additional AMD-associated variants are located in several other complement genes including C3 (Maller et al. 2007; Yates et al. 2007; Spencer et al. 2008b), CFI (Fagerness et al. 2009), and two genes located in the major histocompatibility complex class III region (C2 and CFB) (Gold et al. 2006; Spencer et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Representation of the genetic and environmental influences on AMD susceptibility.

The two major genetic contributors to AMD are variants in the CFH and ARMS2/HTRA1 genes. We will expand further on the CFH and other complement genes associated with AMD in the remainder of the article; however, it is important to note that signals in additional genes have been identified. Briefly, a high-effect locus on chromosome 10q26 was first implicated by linkage analysis in 2004 (Weeks et al. 2004; Fisher et al. 2005) and later confirmed to be associated with AMD (e.g., Jakobsdottir et al. 2005; Rivera et al. 2005; Schmidt et al. 2006; Schwartz et al. 2012). This locus contains three genes, PLEKHA1 (pleckstrin homology domain-containing family A member 1), ARMS2 (age-related maculopathy susceptibility 2; formerly LOC387715), and HTRA1 (HtrA serine peptidase 1), which encompass variants that are strongly associated with AMD (odds ratios exceeding 10 [e.g., Dewan et al. 2006]). Because of the strong linkage disequilibrium across this region, discerning the true associated variant(s) continues to prove difficult (for a recent and comprehensive review, refer to Wang 2014). Additionally, the function of ARMS2 remains largely unknown and functional studies have been inconsistent regarding the role of this protein in AMD (reviewed in Wang 2014). Although the function of HTRA1 is better understood and it can be argued that it makes a better functional candidate, results from functional analyses of the implicated variants have been largely inconsistent as well (reviewed in Wang 2014).

More recently discovered variants associated with AMD reside within and/or near genes ADAMTS9, B3GALTL, CETP, COL8A1-FILIP1L, IER3-DDR1, LIPC, RAD51B, SLC16A8, TGFBR1, and TIMP3 (for more information, refer to Chen et al. 2010; Neale et al. 2010; Fritsche et al. 2013). We focus the remainder of the article specifically on genetic contributors to AMD that are related to the complement system.

It has been well established that inflammatory and immunologic mediators play key roles in the pathogenesis of AMD (e.g., Penfold et al. 1985; Hageman et al. 2001; Anderson et al. 2002, 2010; Patel and Chan 2008; Ding et al. 2009). In 1985, Penfold and colleagues detected inflammatory and immunologic hallmarks in lesions of AMD (Penfold et al. 1985). Since then, the role of immunological events and inflammatory mediators in AMD has been well studied both from functional and genetic aspects. Hallmarks of advanced AMD, including drusen and retinal lesions, promote inflammatory and immune responses including recruitment of macrophages, accumulation of microglia cells, activation of complement, release of cytokines and chemokines, and oxidative stress (Tuo et al. 2012).

Following the functional implication for the complement system in AMD, genetic studies of this relationship exploded. However, the success of these studies was limited. Targeted candidate gene studies seeking to reveal genetic differences accounting for the high prevalence of AMD by analyzing variants in suspected disease genes were unsuccessful (Tuo et al. 2004). Multiple family-based whole-genome linkage scans localized chromosomal regions with evidence of linkage to AMD (Klein et al. 1998; Weeks et al. 2000, 2001, 2004; Majewski et al. 2003; Seddon et al. 2003; Abecasis et al. 2004; Iyengar et al. 2004), including specifically the chromosome 1q25-q32 region first identified by Klein and colleagues (Klein et al. 1998). In this study, a linkage peak on chromosome 1q25-q31 was identified in a large family with high prevalence of AMD. This region was later repeatedly confirmed by additional linkage studies (Majewski et al. 2003; Seddon et al. 2003; Abecasis et al. 2004; Iyengar et al. 2004; Weeks et al. 2004), which also implicated this region of chromosome 1 (also known as ARMD1) as having a role in AMD. With few exceptions (such as chromosome 1), these multitudes of genetic linkage studies did not confirm each other’s results, and the overall genetic picture remained unclear. Fortunately, when these studies were combined into a large scale meta-analysis, some consistently supported regions were identified, including chromosomes 1, 4, 10, and 16 (Fisher et al. 2005).

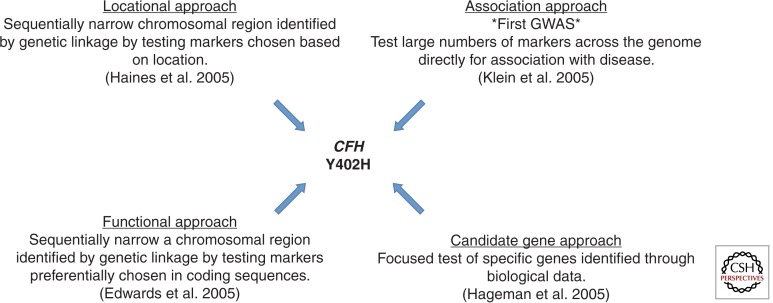

Following these linkage study reports, multiple research groups began to explore additional methods for more focused detection of disease-associated variants. The convergence of four different approaches led to the discovery and confirmation of the first AMD-associated gene on chromosome 1, CFH, which encodes the complement factor H protein (Fig. 2). In one of the first GWA studies ever performed and reported, implementing a hypothesis-free approach of interrogating large numbers of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for association with AMD, Klein et al. (2005) screened 96 AMD cases and 50 non-AMD controls to evaluate variants associated with disease. The data set was derived from part of the age-related eye disease study (AREDS 1999) and the individuals were of self-reported non-Hispanic white ethnicity. This analysis interrogated >116,000 SNPs across the genome. Of the 116,204 successfully genotyped SNPs, intronic SNP rs380390, located within CFH on chromosome 1q31, was strongly associated with AMD (P < 10−7). Linkage disequilibrium analysis of SNPs in the large 41 kb haplotype block revealed a risk haplotype that increases the risk for AMD by a factor of 7.4. To further localize the signal detected, CFH exons and the intronic region containing rs380390 were resequenced to isolate potential functional polymorphisms in the region. The most strongly associated nonsynonymous SNP implicated in this analysis was rs1061170; this polymorphism causes the substitution of a histidine for a tyrosine at amino acid 402 (Y402H) in exon 9 of CFH.

Figure 2.

Four genetic approaches converge to facilitate the discovery of the CFH Y402H AMD susceptibility variant.

Simultaneously and independently, a second study implemented a completely different study design that used a purely locational genomic approach. It also implicated the Y402H variant in AMD (Haines et al. 2005). Focusing on the 24 Mb region implicated in several linkage studies of AMD (Abecasis et al. 2004; Iyengar et al. 2004; Weeks et al. 2004) and extending slightly beyond this region, this study genotyped 61 SNPs in two independent data sets comprised of family-based and case-control samples. A five-SNP haplotype spanning a 261 kb region and encompassing the regulators of complement activation (RCA) gene cluster was associated in both the family and case-control data sets. They next screened the coding region of CFH for risk variants by sequencing 48 individuals homozygous for the associated haplotype. In this analysis, which included 24 AMD cases and 24 non-AMD controls, 11 variants were detected, including rs1061170 (Y402H), which was by far the most significantly associated with AMD. When the sequencing data was expanded and Y402H genotyped in the full family and an independent case-control data set, it was significantly associated with AMD (P = 6 × 10−5). Interestingly, the odds ratio for AMD in carriers of one C allele was 2.45 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.41–4.25), whereas in homozygous C carriers, the odds ratio was 3.33 (CI: 1.79–6.20). When restricted to only individuals with neovascular AMD, odds ratios increased to 3.45 (95% CI: 1.72–6.92) and 5.57 (95% CI: 2.52–12.27), respectively, for heterozygous and homozygous risk allele carriers. The population attributable risk (PAR) for carrying one or more risk alleles was 43% (95% CI: 23%–68%), indicating that quite a large portion of AMD could be attributed specifically to this variant.

Also simultaneously and using yet another independent and complimentary approach, Edwards and colleagues (Edwards et al. 2005) also identified the Y402H variant. This group applied a focused fine-mapping method centered on the chromosome 1 ARMD1 region, which had been previously implicated in a linkage study of AMD (Edwards et al. 2005) but, unlike the Haines et al. (2005) study, this group focused preferentially on markers in coding sequences. The region was interrogated with a total of 86 SNPs spanning the RCA locus in a discovery sample of 224 cases and 133 controls. Of the associated variants, all 29 were located within the RCA; the most significant polymorphism was rs1061170 (Y402H) in CFH. Confirmatory support for this SNP’s involvement in AMD was evident in replication analysis in which 14 SNPs were genotyped in 176 cases and 68 controls, and rs1061170 was again associated. The attributable fraction for rs1061170 in this study was 50%, indicating that individuals carrying the C allele accounted for approximately half of AMD cases.

Hageman and colleagues (2005) again confirmed the Y402H variant, applying yet a fourth genetic analysis method. They applied their prior knowledge of the involvement of CFH (also called HF1) in membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) type II (MPGNII). These patients develop ocular drusen similar to those found in AMD patients, and the genetic lesion for MPGNII also resides within the 1q31-32 region. Thus they evaluated CFH (HF1) sequence variants for association with AMD in addition to examining gene transcription and protein distribution in the macular RPE/choroid complex from controls and AMD patients (Hageman et al. 2005). Evaluating two samples of unrelated individuals including 404 and 550 cases and 131 and 275 controls, respectively, for variation in CFH associated with AMD, their results implicated two common missense variants that showed highly significant associations (I62 V, P = 3.2 × 10−7; and Y402H, P = 1.6 × 10−13). Thus, these results again supported the involvement of Y402H in AMD but also indicated that multiple CFH variants mediate risk for AMD. Functional evaluation of macula from controls and AMD patients indicated that CFH accumulates within drusen and is synthesized by the RPE, thus further supporting the physiologic role of CFH in AMD.

These four complimentary studies provided confirmation and signal localization for the chromosome 1 regions highlighted in linkage studies of AMD (Abecasis et al. 2004; Iyengar et al. 2004; Weeks et al. 2004). In addition to the pivotal knowledge gained from the four approaches, these studies also supported the novel genetic analysis approach known as the GWA study by confirming not only the same region, but the same SNP, as being associated with AMD. The convergence of these four different and independently performed studies provided the field of genetics and disease gene discovery with the necessary confidence in the newly defined GWA method to encourage its application to numerous other diseases. More than 2000 GWA studies have now been published (Welter et al. 2014).

The discovery of the CFH variant, which so powerfully influences AMD risk, spurred various analyses of this and additional complement genes in attempts to elucidate variants mediating AMD risk beyond the initially implicated Y402H in CFH. Multiple additional studies explored the CFH region, with varied success. Seeking to confirm the CFH signal, Maller and colleagues evaluated a sample of 2172 unrelated European-descended individuals including 1238 AMD cases and reported a second signal in a CFH intron (rs1410996, P = 2.65 × 10−61) that remained associated (P < 10−9) after conditioning on Y402H (Maller et al. 2006). Although they performed dense mapping of this region, no other SNPs remained associated after conditioning on Y402H and rs1410996.

To characterize the genetic architecture of CFH and five CFH-related genes (CFHR1-5), Hughes et al. genotyped a region spanning these genes in 173 severe neovascular AMD cases and 170 elderly AMD-free controls; this analysis confirmed two strongly associated haplotypes that appeared to be conferring protection from AMD (Hughes et al. 2006). Haplotype 5, which was detected in ∼20% of control and only 7.8% of case chromosomes in their discovery sample, was independent of the risk variant Y402H (Hughes et al. 2006). Genotyping Y402H and haplotype 5 SNPs in an additional sample of 192 AMD cases and 192 elderly controls confirmed the haplotype 5 frequency in each group (Hughes et al. 2006). In an effort to determine the source of the haplotype 5 protective effect, exon sequencing was performed on CFH and CFHR1; this analysis detected a deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3 (Hughes et al. 2006). The encoded proteins were absent from the serum of individuals homozygous for the protective haplotype 5 (Hughes et al. 2006). Further analyses confirmed this protective effect and the independence of this effect from the Y402H variant (e.g., Spencer et al. 2008a; Fritsche et al. 2010; Sawitzke et al. 2011), although results for the level of significance the deletion contributes to protection from AMD varied (e.g., Spencer et al. 2008b). Further exploring CFH, Spencer and colleagues evaluated previously reported (Hageman et al. 2005) CFH haplotypes and the interaction of smoking status with these in a sample of 584 AMD cases and 248 controls and an additional analysis of 201 families (Spencer et al. 2007). They identified and confirmed two CFH haplotypes associated (P = 0.001, P = 0.077, respectively) with protection from AMD and also detected nominal evidence (P = 0.04) for an interaction between smoking and a protective haplotype, thus providing evidence for the involvement of interaction between a complement component and smoking in AMD risk.

Beyond CFH, various studies sought to evaluate the role of additional compliment mediators in AMD. Because CFH is an activator of the alternative complement pathway, Gold et al. (2006) hypothesized that other activators of this pathway might also be associated with AMD. Initially scanning 18 exons of the factor B-encoding gene BF, which is paralogous to complement component 2 (C2), in 180 AMD cases and controls, this group detected two sequence variants that were more frequent in controls—the L9H and R32Q mutations. The L9H variant in BF is in near complete linkage disequilibrium (i.e., is always inherited together with the E318D C2 variant). Additionally, the R32Q variant is in nearly complete linkage disequilibrium with intronic C2 SNP rs547154; these variants are highly protective against AMD, which was supported by replication analysis performed by this group. Combined analysis of BF/C2 variation in combination with the CFH Y402H variant indicated that 74% of cases and 56% of controls were predictable when these data were available. These variants were confirmed shortly thereafter by Maller and colleagues (2006), who further investigated the evolutionary history of the alleles and determined that the rare, protective variants arose on two distinct haplotypes and likely independently influence AMD risk for AMD.

Exploring complement cascade components beyond CFH and C2/CFB for involvement in AMD, Yates et al. (2007) genotyped 13 SNPs in C3 and C5, key complement cascade proteins, in three European case-control groups. Evaluating two data sets of English ancestry with a total of 603 cases and 350 controls, no variants in C5 were associated with AMD; however, strong evidence of association was detected at rs2230199, which encodes amino acid substitution R120G (P = 5.9 × 10−5) in C3. The variant replicated in a Scottish cohort of 244 cases and 351 controls (P = 5.0 × 10−5); odds ratios for risk allele heterozygotes and homozygotes, were 1.7 (95% CI 1.3–2.1) and 2.6 (95% CI 1.6–4.1), respectively, with an estimated population attributable risk of 22%, thus implicating C3 and further supporting the role of the complement pathway in AMD pathogenesis. This variant again replicated in an independent sample of 2172 primarily European descent individuals including 1238 cases (Maller et al. 2007). Resequencing of C3 identified a nonsynonymous SNP in moderate linkage disequilibrium (r2 = ∼0.53 in this data set) with R80G (rs1047286, L314P) (Maller et al. 2007); conditional analysis confirmed that the R102G polymorphism is likely the causal variant in C3 (Spencer et al. 2008b).

Also seeking to evaluate complement components potentially involved in AMD beyond the previously implicated ones, Fagerness and colleagues performed targeted genotyping of 1500 SNPs in genes falling under suggestive linkage peaks identified in Fisher et al. (2005) as well as complement genes not in those regions (Fagerness et al. 2009). This analysis was performed in a study population of 2053 unrelated Caucasians ≥60 years of age including 1228 dry and wet AMD cases. The most significantly associated variant, which was surrounded by suggestively associated SNPs, was rs10033900 (P = 9.11 × 10−8), which is 2.8 kb upstream of the 3′ UTR of the complement factor I (CFI) gene. Dense follow-up genotyping in the region surrounding rs10033900 followed by conditional association analysis did not reveal any variants with greater significance than the original associated SNP. Haplotype analysis in the region implicated rs13117504 and rs10033900 together (P = 1.18 × 10−8) were more strongly associated with AMD than the single SNP, although neither SNP is thought to be functional.

Another group seeking to clarify the role of additional complement genes in AMD, Stanton and colleagues explored the role of complement factor D (CFD) in AMD by genotyping two SNPs in six separate case-control samples of European descent (Stanton et al. 2011). Their analysis of a total of 4765 individuals including 2833 AMD cases detected that rs3826945 was associated with AMD, although it replicated almost solely in females.

Additional approaches to clarify the role of complement in AMD have not all been met with success. Further exploring the AMD association with additional complement pathway genes beyond those thus far described has been a major focus for groups seeking to genetically explain AMD risk and pathogenesis. Implementing a candidate gene approach and exploring 20 SNPs in four complement genes—CFP, CD46, CD55, and CD59 in 446 AMD cases and 262 controls, Cipriani and colleagues (2012) did not detect association.

Additional GWA studies on individual data sets beyond the first reported in AMD have been met with limited success beyond replication of known signals. Ryu and colleagues (2010) performed a GWA study in 593 non-Hispanic white subjects from the age-related eye disease study (AREDS) in which 109,270 SNPs were interrogated and analyzed for association with AMD. Replication was performed in an independent data set of 444 AMD cases and 300 non-AMD controls. Loci in previously implicated complement genes CFH, CFB, and C3 replicated association in this analysis, although no novel variants were detected. A recently reported GWA study examined 400 AMD cases with an interesting set of controls—400 individuals with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) with no history, clinical signs, or symptoms of AMD (Scheetz et al. 2013). Samples were genotyped at 500,000 loci on the Affymetrix 500 k and Mapping 5.0 arrays; this method, although presenting its own challenges in terms of disease phase of given association, is a time- and cost-effective approach. Although previously detected loci in CFH and ARMS2-HTRA1-PLEKHA1 were associated in this analysis along with several other previously implicated loci, no novel associations were detected.

META-ANALYSIS OF GWA STUDIES

Although the GWA approach has been informative for numerous studies since those first reported in the mid-2000s (Welter et al. 2014), a substantial proportion of genetic etiology of GWAS studied diseases has yet to be explained; this is true for AMD, in which identified risk variants are estimated to account for 15%–65% of the genetic portion of AMD (Manolio et al. 2009). Approaches to enhance the detection of genetic variation associated with disease have grown beyond the traditional GWA approach and include imputing variants using known genetic information for a reference sample, performing conditional analyses, and implementing pathway analyses.

Increasing sample size of studies is crucial, as large sample sizes of cases and controls accelerate the identification of genetic variation associated with the disease of interest. Beyond increasing the number of samples tested, increasing the number of variants tested has also become a more attainable goal by performing imputation on GWA data. Imputation is a technique that greatly increases the number of tested variants beyond those interrogated in a GWA study by inferring genotypes of untyped SNPs. Combining known genotypes at GWA-interrogated SNPs with DNA sequences from a reference panel, genotypes at numerous SNPs can then be inferred with varying degrees of confidence and accuracy. Imputation not only increases the power of GWA studies by increasing the number of SNPs that can be tested, it can also lead to more efficient identification of causal variants and/or SNPs in high-linkage disequilibrium with a causal variant (Marchini and Howie 2010; Li et al. 2009). Imputation has been implemented in several studies of AMD to enhance the ability to detect associated variants (Fritsche et al. 2013; Helgason et al. 2013; Seddon et al. 2013).

Studies that bring together the described techniques substantially increase the value of GWA data. In the most recent publication from the AMD Gene Consortium (Fritsche et al. 2013), seven novel variants were detected by using GWA data beyond traditionally implemented methods. Using GWA data from 7650 advanced AMD cases and 51,844 controls and imputing to the HapMap II human variation reference dataset (Frazer et al. 2007), the Consortium evaluated nearly 2.5 million total SNPs. Of these, 32 were further evaluated in an additional 9531 cases and 8230 controls. Joint analysis detected 19 total loci attaining genome-wide significance at P < 5 × 10−8. Significant loci included 12 previously identified variants in ARMS2-HTRA1, CFH, C2-CFB, C3, TIMP3, APOE, CETP, VEGFA, TNFRSF10A, LIPC, CFI, and COL10A1, with odds ratios ranging from 1.13 (COL10A1) to 2.71 (ARMS2-HTRA1). An additional seven variants in COL8A1-FILIP1L, IER3-DDR1, SLC16A8, TGFBR1, RAD51B, ADAMTS9, and B3GALTL met genome-wide significance for the first time, with odds ratios ranging from 1.11 (RAD51B) to 1.28 (COL8A10-FILIP1L) (Fritsche et al. 2013).

This study also went beyond traditional GWA methods by exploring stratification by AMD subtype, gender, and ancestry. Of particular interest, CFH risk alleles associated preferentially with geographic atrophy risk when compared with choroidal neovascularization, and had stronger evidence of association in Europeans compared with Asians. Interaction analyses, which explored whether pairs of risk alleles occurring together conferred higher risk than alleles occurring alone, highlighted one interaction between SNPs near CFH and C2-CFB in which carriers of risk alleles at both loci were at slightly higher risk for AMD than what would normally be expected. These results further confirmed the importance of the complement system in AMD and provided the best overall estimates of the effect sizes for each of the implicated variants to date.

Pathway enrichment analyses are used to identify biological relationships between biologically associated genetic signals and pathways of interest in a particular disease. These are implemented by evaluating GWA results for SNPs to assess overrepresentation in particular biological pathways and serve to evaluate signals that could be biologically meaningful but are overlooked amidst numerous potentially false-positive results (Yaspan et al. 2011). Thus, pathway analyses provide insight to the functional aspects of a disease by evaluating GWA results in a broader manner than single-SNP analyses, and can identify potentially meaningful relationships for SNPs other than those attaining a specific p-value cutoff. Such results may highlight additional small and/or interactive effects that are important to evaluate in addition to and in the context of the overall GWA results. The most recent publication of the AMD Gene Consortium reported implementing INRICH (Interval-based Enrichment Analysis Tool for Genome Wide Association Studies) pathway analysis (Lee et al. 2012) to evaluate overall results (Fritsche et al. 2013). While confirming previously implicated AMD pathways, this analysis also highlighted additional pathways of interest; among the seven new loci, there was enrichment for genes encoding proteins in the complement and atherosclerotic pathways in addition to genes encoding collagen and extracellular region proteins, complement and coagulation cascades, lipoprotein metabolism, and regulation of apoptosis (Fritsche et al. 2013).

BEYOND GWA STUDIES

Whole exome and whole genome sequencing are additional approaches that investigate far beyond the genome-wide arrays, and their utility is just starting to be realized in AMD. These confer the ability to evaluate rare and low-frequency variants, which have been implicated as a potential source of missing heritability in many diseases with a genetic component (Manolio et al. 2009). AMD, having nearly one-third of the genetic component of the disease unexplained, has been investigated in several rare variant studies (e.g., Raychaudhuri et al. 2011; Gu et al. 2013; Helgason et al. 2013; Seddon et al. 2013; van de Ven et al. 2013; Zhan et al. 2013). In two recent publications, the role of rare variation was explored on a large scale. Helgason et al. whole-genome sequenced 2230 Icelandic samples and used these data to impute 34.2 million SNPs and short insertions/deletions using Illumina array data from 95,085 Icelanders. Variants were then tested for association with AMD in 1143 Icelanders with AMD and 51,435 controls; no new loci were detected that attained genome-wide significance thresholds. Applying conditional analyses to previously implicated loci, they searched for independent signals and detected a rare variant in C3, rs14785925, which codes for a Lys155Gln substitution, present at <1% frequency in their sample, that appears to be independent of previously reported Arg102Gly and Pro314Leu (Helgason et al. 2013) variants. This type of analysis is important for deciphering residual signals at previously reported loci—as evidenced by the lack of significant signals after conditioning on both the Pro314Leu and newly discovered Lys155Gln variants.

Another recent study discovered rare variants in three genes, CFI, C3, and C9 that are associated with AMD by applying targeted next-generation sequencing to coding regions of candidate genes in AMD-associated loci and pathways (Seddon et al. 2013). This analysis evaluated 681 genes in 1676 AMD cases prioritized for extreme phenotype (severe disease, familial disease, and early age of onset), 745 controls and 36 siblings discordant for AMD (Seddon et al. 2013). Evaluating coding variants present at <1% frequency and applying burden testing identified CFI as having an increased burden of rare variation in cases compared with controls, independent of the known rs4698775 risk variant. They additionally tested 1824 rare (frequency <1% variants present at least five times) individually for association with AMD; 11 variants were followed up in an independent sample of 2227 cases and 2888 controls.

ADDITIONAL FUNCTIONAL STUDIES

The ability to relate functional data to genetic data can greatly increase the interpretation of the genetic data. The AMD Gene Consortium found that CFH mRNA was differentially expressed in postmortem retina of young and elderly individuals (Fritsche et al. 2013). In addition, C3 expression was higher in adult compared with fetal RPE, and all complement genes that were expressed at detectable levels in the retina or RPE were expressed at higher levels in tissue from older individuals. Thus, functional data linked with genetic data is incredibly informative and clearly still implicates the complement system in AMD pathogenesis.

Current efforts in genetic studies of AMD require implementation of all described methods, in addition to developing new analyses and experiments for further parsing out the role of complement and other biological systems in AMD susceptibility and pathogenesis. Analysis of data from exome chips, designed to jointly interrogate data relevant to association studies of common variants and sequencing studies of rare variants, will improve various aspects of genetic analysis of AMD. These data will provide greater coverage of known disease susceptibility loci via fine mapping, improve discovery of novel disease loci, and provide means for rare coding and copy number variant analysis. With new technology undoubtedly comes the challenge of implementing new analysis methods. For instance, most variants interrogated on exome arrays are quite rare; therefore, single variant analysis may not yield results that are truly representative of the impact of a specific region on disease risk. To address this challenge, data will be evaluated by aggregating sets of low-frequency variants associated with disease (e.g., applying burden testing). One particular method for burden testing designed to detect association signals distributed over multiple variants is the sequence kernel association test (SKAT) method, which allows for the incorporation of flexible weight functions, thereby allowing, for example, one to increase the weight of variants with lower minor allele frequencies and decrease the weight of variants inferred with lower confidence (in the case of imputed data) (Wu et al. 2011). Such analysis techniques will be crucial to moving forward future analyses that will clarify the molecular mechanisms linking known loci to disease.

The goal of the above described and additional ongoing studies is to improve the current comprehension of new and existing disease loci, as well as to improve the prediction of individual phenotypes to increase the knowledge of AMD biology in hopes of ultimately facilitating the development of better strategies for disease treatment and prevention.

GENETIC RISK SCORES

As the focus of biomedical research transitions toward personalized medicine, genetic studies now have the task of not only detecting variants that mediate disease risk but also assessing whether those variants interact with known environmental and clinical factors (and whether there is clinical utility for this knowledge in the current or future medical setting). The most comprehensive case-control analysis in AMD in a recent report from the AMD Gene Consortium indicates that risk scores based on the now 19 known common SNPs mediating risk for AMD are able to distinguish fairly well between case and control individuals (Fritsche et al. 2013), although it is not clear that the most recently identified variants contribute a great deal of information regarding disease risk beyond what prior known SNPs indicate. Other studies have evaluated the utility of categorized risk intervals based on genetic variation solely and in addition to known environmental contributors with generally positive results (e.g., Ho et al. 2011; Spencer et al. 2011; Grassmann et al. 2012). Beyond simple genetic risk score analysis, the interaction of genetic risk with environmental factors is also valuable not only clinically but to further elucidate mechanisms of disease susceptibility and pathogenesis. For example, Spencer and colleagues developed an algorithm using genetic profile and smoking history that was able to categorize individuals into high- and low-risk profiles for AMD (Spencer et al. 2011). In addition, Buitendijk et al. (2013) show that, although the difference is perhaps not clinically significant, the best statistical model for predicting AMD is attained when genetic as well as environmental factors are included. This type of model does not add a great deal of information beyond what is indicated from a clinically integrated evaluation that includes only age, sex, AMD baseline grade, smoking, and BMI, although the difference is statistically significant (Buitendijk et al. 2013). As phenotyping improves, additional genetic variants involved in AMD will likely be detected, and their role in disease more clearly defined (Ratnapriya and Chew 2013). Additionally, the role of environmental factors and their interactions with genetic variation must continue to be elucidated; thus, before the full utility of genetic risk scores can be applied in AMD, the genetic architecture must continue to be unraveled (Ratnapriya and Chew 2013), within and beyond the contribution of complement and other known genetic mediators of disease.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

That there is a role for complement in AMD is overwhelmingly supported by genetic and physiologic evidence. As biomedical research continues to elucidate the mechanisms by which complement contributes to the pathology of this disease, increasingly sophisticated techniques will be applied to analyzing and interpreting genetic data. Ongoing and planned studies interrogate the entire exome, even the entire genome, in hopes of gaining additional knowledge pertinent to the pathophysiology of AMD. Additionally, better characterizing the contributions of known risk loci will be important to continue to clarify the molecular mechanisms linking these to disease. The ultimate overall goal of these efforts is to increase the understanding of AMD biology so that better strategies for disease treatment and prevention can be developed and implemented.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants EY012118 (J.L.H., M.A.P.V.), EY023164 (J.L.H., M.A.P.V.), T32 EY007157 (J.N.C.B.), and T32 EY21453-2 (J.N.C.B.).

Footnotes

Editors: Eric A. Pierce, Richard H. Masland, and Joan W. Miller

Additional Perspectives on Retinal Disorders: Genetic Approaches to Diagnosis and Treatment available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Abecasis GR, Yashar BM, Zhao Y, Ghiasvand NM, Zareparsi S, Branham KE, Reddick AC, Trager EH, Yoshida S, Bahling J, et al. 2004. Age-related macular degeneration: A high-resolution genome scan for susceptibility loci in a population enriched for late-stage disease. Am J Hum Genet 74: 482–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. 1999. The age-related eye disease study (AREDS): Design implications. AREDS report no. 11. Control Clin Trials 20: 573–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Mullins RD, Hageman GS, Johnson LV 2002. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol 134: 411–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DH, Radeke MJ, Gallo NB, Chapin EA, Johnson PT, Curletti CR, Hancox LS, Hu J, Ebright JN, Malek G, et al. 2010. The pivotal role of the complement system in aging and age-related macular degeneration: Hypothesis re-visited. Prog Retin Eye Res 29: 95–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird PN, Islam FM, Richardson AJ, Cain M, Hunt N, Guymer R 2006. Analysis of the Y402H variant of the complement factor H gene in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 47: 4194–4198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitendijk GH, Rochtchina E, Myers C, van Duijn CM, Lee KE, Klein BE, Meuer SM, de Jong PT, Holliday EG, Tan AG, et al. 2013. Prediction of age-related macular degeneration in the general population: The three continent AMD consortium. Ophthalmology 120: 2644–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Stambolian D, Edwards AO, Branham KE, Othman M, Jakobsdottir J, Tosakulwong N, Pericak-Vance MA, Campochiaro PA, Klein ML, et al. 2010. Genetic variants near TIMP3 and high-density lipoprotein-associated loci influence susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 7401–7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani V, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Shahid H, Stanton CM, Hayward C, Wright AF, Bunce C, Clayton DG, Moore AT, et al. 2012. Genetic variation in complement regulators and susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Immunobiology 217: 158–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons TE, Milton RC, Klein R, Seddon JM, Ferris FL III 2005. Risk factors for the incidence of advanced age-related macular degeneration in the age-related eye disease study (AREDS) AREDS report no. 19. Ophthalmology 112: 533–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley YP, Jakobsdottir J, Mah T, Weeks DE, Klein R, Kuller L, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB 2006. CFH, ELOVL4, PLEKHA1 and LOC387715 genes and susceptibility to age-related maculopathy: AREDS and CHS cohorts and meta-analyses. Hum Mol Genet 15: 3206–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeAngelis MM, Silveira AC, Carr EA, Kim IK 2011. Genetics of age-related macular degeneration: Current concepts, future directions. Semin Ophthalmol 26: 77–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degn SE, Jensenius JC, Thiel S 2011. Disease-causing mutations in genes of the complement system. Am J Hum Genet 88: 689–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewan A, Liu M, Hartman S, Zhang SS, Liu DT, Zhao C, Tam PO, Chan WM, Lam DS, Snyder M, et al. 2006. HTRA1 promoter polymorphism in wet age-related macular degeneration. Science 314: 989–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Patel M, Chan CC 2009. Molecular pathology of age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 28: 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AO, Ritter R III, Abel KJ, Manning A, Panhuysen C, Farrer LA 2005. Complement factor H polymorphism and age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerness JA, Maller JB, Neale BM, Reynolds RC, Daly MJ, Seddon JM 2009. Variation near complement factor I is associated with risk of advanced AMD. Eur J Hum Genet 17: 100–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher SA, Abecasis GR, Yashar BM, Zareparsi S, Swaroop A, Iyengar SK, Klein BE, Klein R, Lee KE, Majewski J, et al. 2005. Meta-analysis of genome scans of age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 14: 2257–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazer KA, Ballinger DG, Cox DR, Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Gibbs RA, Belmont JW, Boudreau A, Hardenbol P, Leal SM, et al. 2007. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449: 851–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche LG, Loenhardt T, Janssen A, Fisher SA, Rivera A, Keilhauer CN, Weber BH 2008. Age-related macular degeneration is associated with an unstable ARMS2 (LOC387715) mRNA. Nat Genet 40: 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche LG, Lauer N, Hartmann A, Stippa S, Keilhauer CN, Oppermann M, Pandey MK, Kohl J, Zipfel PF, Weber BH, et al. 2010. An imbalance of human complement regulatory proteins CFHR1, CFHR3 and factor H influences risk for age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Hum Mol Genet 19: 4694–4704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsche LG, Chen W, Schu M, Yaspan BL, Yu Y, Thorleifsson G, Zack DJ, Arakawa S, Cipriani V, Ripke S, et al. 2013. Seven new loci associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 45: 433–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold B, Merriam JE, Zernant J, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Gehrs K, Cramer K, Neel J, Bergeron J, Barile GR, et al. 2006. Variation in factor B (BF) and complement component 2 (C2) genes is associated with age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38: 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassmann F, Fritsche LG, Keilhauer CN, Heid IM, Weber BH 2012. Modelling the genetic risk in age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE 7: e37979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu BJ, Baird PN, Vessey KA, Skarratt KK, Fletcher EL, Fuller SJ, Richardson AJ, Guymer RH, Wiley JS 2013. A rare functional haplotype of the P2RX4 and P2RX7 genes leads to loss of innate phagocytosis and confers increased risk of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J 27: 1479–1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, Johnson LV, Anderson DH, Mullins RF 2001. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 20: 705–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman GS, Anderson DH, Johnson LV, Hancox LS, Taiber AJ, Hardisty LI, Hageman JL, Stockman HA, Borchardt JD, Gehrs KM, et al. 2005. A common haplotype in the complement regulatory gene factor H (HF1/CFH) predisposes individuals to age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 7227–7232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines JL, Hauser MA, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Olson LM, Gallins P, Spencer KL, Kwan SY, Noureddine M, Gilbert JR, et al. 2005. Complement factor H variant increases the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CJ, Webster AR, Snieder H, Bird AC, Gilbert CE, Spector TD 2002. Genetic influence on early age-related maculopathy: A twin study. Ophthalmology 109: 730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgason H, Sulem P, Duvvari MR, Luo H, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Jonsdottir I, Masson G, Gudbjartsson DF, Walters GB, et al. 2013. A rare nonsynonymous sequence variant in C3 is associated with high risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 45: 1371–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L, van LR, Witteman JC, van Duijn CM, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, de Jong PT, Vingerling JR, Klaver CC 2011. Reducing the genetic risk of age-related macular degeneration with dietary antioxidants, zinc, and ω-3 fatty acids: The Rotterdam study. Arch Ophthalmol 129: 758–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AE, Orr N, Esfandiary H, Diaz-Torres M, Goodship T, Chakravarthy U 2006. A common CFH haplotype, with deletion of CFHR1 and CFHR3, is associated with lower risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38: 1173–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar SK, Song D, Klein BE, Klein R, Schick JH, Humphrey J, Millard C, Liptak R, Russo K, Jun G, et al. 2004. Dissection of genomewide-scan data in extended families reveals a major locus and oligogenic susceptibility for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 74: 20–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsdottir J, Conley YP, Weeks DE, Mah TS, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB 2005. Susceptibility genes for age-related maculopathy on chromosome 10q26. Am J Hum Genet 77: 389–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandhadia S, Cipriani V, Yates JR, Lotery AJ 2012. Age-related macular degeneration and the complement system. Immunobiology 217: 127–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaver CC, Wolfs RC, Assink JJ, van Duijn CM, Hofman A, de Jong PT 1998. Genetic risk of age-related maculopathy. Population-based familial aggregation study. Arch Ophthalmol 116: 1646–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein BE, Klein R 2007. Lifestyle exposures and eye diseases in adults. Am J Ophthalmol 144: 961–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein ML, Mauldin WM, Stoumbos VD 1994. Heredity and age-related macular degeneration. Observations in monozygotic twins. Arch Ophthalmol 112: 932–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein ML, Schultz DW, Edwards A, Matise TC, Rust K, Berselli CB, Trzupek K, Weleber RG, Ott J, Wirtz MK, et al. 1998. Age-related macular degeneration. Clinical features in a large family and linkage to chromosome 1q. Arch Ophthalmol 116: 1082–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RJ, Zeiss C, Chew EY, Tsai JY, Sackler RS, Haynes C, Henning AK, SanGiovanni JP, Mane SM, Mayne ST, et al. 2005. Complement factor H polymorphism in age-related macular degeneration. Science 308: 385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, O’Dushlaine C, Thomas B, Purcell SM 2012. INRICH: Interval-based enrichment analysis for genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics 28: 1797–1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Willer C, Sanna S, Abecassis G 2009. Genotype imputation. Ann Rev Hum Genet 10: 387–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewski J, Schultz DW, Weleber RG, Schain MB, Edwards AO, Matise TC, Acott TS, Ott J, Klein ML 2003. Age-related macular degeneration—A genome scan in extended families. Am J Hum Genet 73: 540–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller J, George S, Purcell S, Fagerness J, Altshuler D, Daly MJ, Seddon JM 2006. Common variation in three genes, including a noncoding variant in CFH, strongly influences risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 38: 1055–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller JB, Fagerness JA, Reynolds RC, Neale BM, Daly MJ, Seddon JM 2007. Variation in complement factor 3 is associated with risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 39: 1200–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, McCarthy MI, Ramos EM, Cardon LR, Chakravarti A, et al. 2009. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461: 747–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchini J, Howie B 2010. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet 11: 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SM 1994. A twin study on age-related macular degeneration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 92: 775–843. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SM, Greene T, Gutman FA 1995. A twin study of age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 120: 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW 2013. Age-related macular degeneration revisited—Piecing the puzzle: The LXIX Edward Jackson memorial lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 155: 1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan BP 1995. Physiology and pathophysiology of complement: Progress and trends. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 32: 265–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale BM, Fagerness J, Reynolds R, Sobrin L, Parker M, Raychaudhuri S, Tan PL, Oh EC, Merriam JE, Souied E, et al. 2010. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 7395–7400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M, Chan CC 2008. Immunopathological aspects of age-related macular degeneration. Semin Immunopathol 30: 97–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfold PL, Killingsworth MC, Sarks SH 1985. Senile macular degeneration: The involvement of immunocompetent cells. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 223: 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnapriya R, Chew EY 2013. Age-related macular degeneration—Clinical review and genetics update. Clin Genet 84: 160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raychaudhuri S, Iartchouk O, Chin K, Tan PL, Tai AK, Ripke S, Gowrisankar S, Vemuri S, Montgomery K, Yu Y, et al. 2011. A rare penetrant mutation in CFH confers high risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 43: 1232–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera A, Fisher SA, Fritsche LG, Keilhauer CN, Lichtner P, Meitinger T, Weber BH 2005. Hypothetical LOC387715 is a second major susceptibility gene for age-related macular degeneration, contributing independently of complement factor H to disease risk. Hum Mol Genet 14: 3227–3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu E, Fridley BL, Tosakulwong N, Bailey KR, Edwards AO 2010. Genome-wide association analyses of genetic, phenotypic, and environmental risks in the age-related eye disease study. Mol Vis 16: 2811–2821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawitzke J, Im KM, Kostiha B, Dean M, Gold B 2011. Association assessment of copy number polymorphism and risk of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 118: 2442–2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheetz TE, Fingert JH, Wang K, Kuehn MH, Knudtson KL, Alward WL, Boldt HC, Russell SR, Folk JC, Casavant TL, et al. 2013. A genome-wide association study for primary open angle glaucoma and macular degeneration reveals novel loci. PLoS ONE 8: e58657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schick JH, Iyengar SK, Klein BE, Klein R, Reading K, Liptak R, Millard C, Lee KE, Tomany SC, Moore EL, et al. 2003. A whole-genome screen of a quantitative trait of age-related maculopathy in sibships from the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Hum Genet 72: 1412–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Hauser MA, Scott WK, Postel EA, Agarwal A, Gallins P, Wong F, Chen YS, Spencer K, Schnetz-Boutaud N, et al. 2006. Cigarette smoking strongly modifies the association of LOC387715 and age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 78: 852–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SG, Agarwal A, Kovach JL, Gallins PJ, Cade W, Postel EA, Wang G, Ayala-Haedo J, Spencer KM, Haines JL, et al. 2012. The ARMS2 A69S variant and bilateral advanced age-related macular degeneration. Retina 32: 1486–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Santangelo SL, Book K, Chong S, Cote J 2003. A genomewide scan for age-related macular degeneration provides evidence for linkage to several chromosomal regions. Am J Hum Genet 73: 780–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon JM, Yu Y, Miller EC, Reynolds R, Tan PL, Gowrisankar S, Goldstein JI, Triebwasser M, Anderson HE, Zerbib J, et al. 2013. Rare variants in CFI, C3 and C9 are associated with high risk of advanced age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 45: 1366–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuler RK Jr, Hauser MA, Caldwell J, Gallins P, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Agarwal A, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Postel EA 2007. Neovascular age-related macular degeneration and its association with LOC387715 and complement factor H polymorphism. Arch Ophthalmol 125: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souied EH, Leveziel N, Richard F, Dragon-Durey MA, Coscas G, Soubrane G, Benlian P, Fremeaux-Bacchi V 2005. Y402H complement factor H polymorphism associated with exudative age-related macular degeneration in the French population. Mol Vis 11: 1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer KL, Hauser MA, Olson LM, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Gallins P, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL 2007. Protective effect of complement factor B and complement component 2 variants in age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 16: 1986–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer KL, Hauser MA, Olson LM, Schmidt S, Scott WK, Gallins P, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL 2008a. Deletion of CFHR3 and CFHR1 genes in age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 17: 971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer KL, Olson LM, Anderson BM, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Scott WK, Gallins P, Agarwal A, Postel EA, Pericak-Vance MA, Haines JL 2008b. C3 R102G polymorphism increases risk of age-related macular degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 17: 1821–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer KL, Olson LM, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Gallins P, Agarwal A, Iannaccone A, Kritchevsky SB, Garcia M, Nalls MA, Newman AB, et al. 2011. Using genetic variation and environmental risk factor data to identify individuals at high risk for age-related macular degeneration. PLoS ONE 6: e17784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton CM, Yates JR, den Hollander AI, Seddon JM, Swaroop A, Stambolian D, Fauser S, Hoyng C, Yu Y, Atsuhiro K, et al. 2011. Complement factor D in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52: 8828–8834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop A, Branham KE, Chen W, Abecasis G 2007. Genetic susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration: A paradigm for dissecting complex disease traits. Hum Mol Genet 16: R174–R182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikellis G, Robman LD, Dimitrov P, Nicolas C, McCarty CA, Guymer RH 2007. Characteristics of progression of early age-related macular degeneration: The cardiovascular health and age-related maculopathy study. Eye (Lond) 21: 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo J, Bojanowski CM, Chan CC 2004. Genetic factors of age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 23: 229–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo J, Grob S, Zhang K, Chan CC 2012. Genetics of immunological and inflammatory components in age-related macular degeneration. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 20: 27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Ven JP, Nilsson SC, Tan PL, Buitendijk GH, Ristau T, Mohlin TC, Nabuurs SB, Schoenmaker-Koller FE, Smailhodzic D, Campochiaro PA, et al. 2013. A functional variant in the CFI gene confers a high risk of age-related macular degeneration. Nat Genet 45: 813–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ 2001a. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 344: 1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport MJ 2001b. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med 344: 1140–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G 2014. Chromosome 10q26 locus and age-related macular degeneration: A progress update. Exp Eye Res 119: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DE, Conley YP, Mah TS, Paul TO, Morse L, Ngo-Chang J, Dailey JP, Ferrell RE, Gorin MB 2000. A full genome scan for age-related maculopathy. Hum Mol Genet 9: 1329–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DE, Conley YP, Tsai HL, Mah TS, Rosenfeld PJ, Paul TO, Eller AW, Morse LS, Dailey JP, Ferrell RE, et al. 2001. Age-related maculopathy: An expanded genome-wide scan with evidence of susceptibility loci within the 1q31 and 17q25 regions. Am J Ophthalmol 132: 682–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks DE, Conley YP, Tsai HJ, Mah TS, Schmidt S, Postel EA, Agarwal A, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Rosenfeld PJ, et al. 2004. Age-related maculopathy: A genomewide scan with continued evidence of susceptibility loci within the 1q31, 10q26, and 17q25 regions 16. Am J Hum Genet 75: 174–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welter D, Macarthur J, Morales J, Burdett T, Hall P, Junkins H, Klemm A, Flicek P, Manolio T, Hindorff L, et al. 2014. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D1001–D1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X 2011. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet 89: 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Camp NJ, Sun H, Tong Z, Gibbs D, Cameron DJ, Chen H, Zhao Y, Pearson E, Li X, et al. 2006. A variant of the HTRA1 gene increases susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Science 314: 992–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaspan BL, Bush WS, Torstenson ES, Ma D, Pericak-Vance MA, Ritchie MD, Sutcliffe JS, Haines JL 2011. Genetic analysis of biological pathway data through genomic randomization. Hum Genet 129: 563–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates JR, Sepp T, Matharu BK, Khan JC, Thurlby DA, Shahid H, Clayton DG, Hayward C, Morgan J, Wright AF, et al. 2007. Complement C3 variant and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med 357: 553–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareparsi S, Branham KE, Li M, Shah S, Klein RJ, Ott J, Hoh J, Abecasis GR, Swaroop A 2005. Strong association of the Y402H variant in complement factor H at 1q32 with susceptibility to age-related macular degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 77: 149–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X, Larson DE, Wang C, Koboldt DC, Sergeev YV, Fulton RS, Fulton LL, Fronick CC, Branham KE, Bragg-Gresham J, et al. 2013. Identification of a rare coding variant in complement 3 associated with age-related macular degeneration 5. Nat Genet 45: 1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]