Abstract

Background:

House officers training has always been regarded as a highly stressful environment to doctors. The objectives of our study were to assess perceived stress and sources of stress among house officers.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was carried out among house officers working in Civil Hospital, Karachi, Pakistan, and Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi, Pakistan, during November and December, 2013. Perceived stress was assessed using perceived stress scale. A 15-item questionnaire was used to assess sources of stress and was graded by Likert scale (1 = very low, 5 = very high). To calculate the difference of mean for stressors by gender of house officers, t-test with 95% confidence interval was used.

Results:

The overall response rate was 81.5% (269 out of 330). One hundred twenty-nine (47.9%) were found to be under stress of whom 32 (24.8%) were males and 97 (75.2%) were females. Top five stressors reported by house officers were night calls, workload, time pressure, working alone, and coping with diagnostic uncertainty. Significant differences for stressors by gender were found for night calls (P < 0.05), unrealistically high expectation by others (P < 0.05), financial issues (P < 0.05), and lack of senior support (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

Majority of house officers working in Civil Hospital, Karachi, and Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi, were under high level of stress. Therefore, immediate steps should be taken for control of stress and its management.

Keywords: Diagnostic uncertainty, house officers, stressors

INTRODUCTION

Stress is the psychological and physical state that results when resources of an individual are not enough to deal with the demands and pressure of the situations.[1] Medicine is an undoubtedly stressful profession with long working hours, ethical dilemmas, and difficult patients. House officers are those who have recently gained a qualification as a doctor and work in a hospital while continuing their training.

Stress has many adverse effects on medical practice, including prescribing errors, lack of team work, more patients’ complaint, and sickness absence. Trainees suffer from high levels of stress, which lead to alcohol and drug abuse, interpersonal relationship difficulties, depression and anxiety, and even suicide.[2] Work-related stress and anxiety can not only affect the doctors’ health, but it may also affect patient care.

Sources of stress among house officers generally can be divided into six groups: Nature of job, interpersonal relationships, organizational working environment, work-family conflicts, and profession prospects.[3] A previous study has shown that intensity of workload, coping with diagnostic uncertainty, working alone, working unsocial hours, and experiencing fatigue play a major role as stressors to house officers.[4] Understanding the nature of stressors may help authorities find ways to reduce unwanted consequences of the stressors on the house officers’ wellbeing in the future.

Based on previous studies, the prevalence and sources of stress among undergraduate and postgraduate trainees is well established, but there is little data for house officers who are considered as firstline service providers in hospitals. Therefore, the purpose of the study is to investigate stress and sources of stress among house officers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was performed at Civil Hospital, Karachi, which is a teaching hospital affiliated to Dow University of Health Sciences, Karachi, and Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Center, Karachi, which is also a teaching hospital affiliated to Jinnah Sindh University. Our participant base was house officers who were working in both the hospitals. A total of 330 house officers were approached with the a questionnaire. Out of 330 house officers, 269 returned the questionnaire. This study utilized a descriptive, cross-sectional, self-administered questionnaire. The study was carried out during November and December, 2013. Each house officer was briefed about the purpose and objective of the study. The house officers were assured about anonymity and confidentiality of the responses given in the questionnaire and instructed to return the completed questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised of demographic data, 14-items perceived stress scale, and 15-items list of potential stressors. The perceived stress was measured using the perceived stress scale (PSS-14),[5] which comprised of 14 questions with responses varying from 0 to 4 for each item and ranging from never, almost never, sometimes, fairly often, and very often, respectively, on the basis of their occurrence during one month prior to the survey. The PSS has an internal consistency of 0.85 (Cronbach α co-efficient) and test-retest reliability during a short retest interval (several days) of 0.85.[5] It assesses the degree to which participants evaluate their lives as being stressful during the past month. It does not tie appraisal to a particular situation; the scale is sensitive to the nonoccurrence of events as well as to the ongoing life circumstances. PSS-14 scores are obtained by reversing the scores on seven positive items, for example, 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2, and so on and then summing across all 14 items. Seven out of the 14 items of PSS-14 are considered positive (4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 13) and the remaining seven as negative (1, 2, 3, 8, 11, 12, 14), representing self-efficacy and perceived helplessness, respectively. The scale yielded a single score with high scores indicating higher levels of stress and lower levels indicating lower levels of stress. The PSS-14 has a possible range of scores from 0 to 56. The upper two and lower two quartiles were combined (28 being the operational cutoff value for the upper bound) and were labeled as stressed and not stressed, respectively. The potential stressors included in the questionnaire were derived by reviewing the literature and by holding informal discussion with a group of house officers. A total of 15 sources of stress were listed, which were working alone, workload, time pressure, night calls, coping with diagnostic uncertainty, worrying about patient complaints, interruption of family life, 24 h responsibility of patients’ life, unrealistically high expectations by others, adverse publicity of doctors’ role by the media, financial issues, competence, lack of career development, lack of senior support, and conflict with staff. The severity of each stressor was measured using a five-point Likert scale (1-5) ranging from very low (1) to very high (5). The data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 17.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean score of perceived stress was calculated. The percentages and mean scores with standard deviation were calculated for stressors. To calculate difference of continuous variables by gender of house officer for stressors by assuming the equal interval between different scores of Likert Scale, t-test with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used and the difference of mean was calculated. A P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

RESULTS

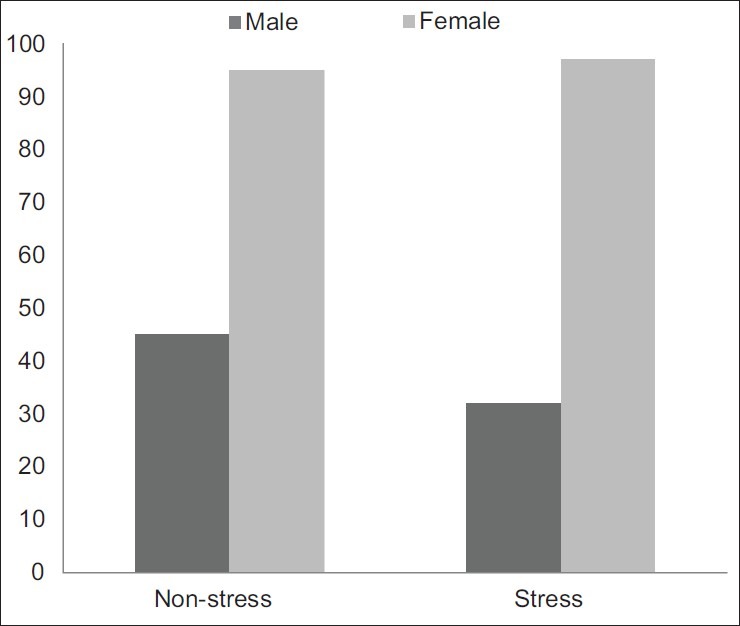

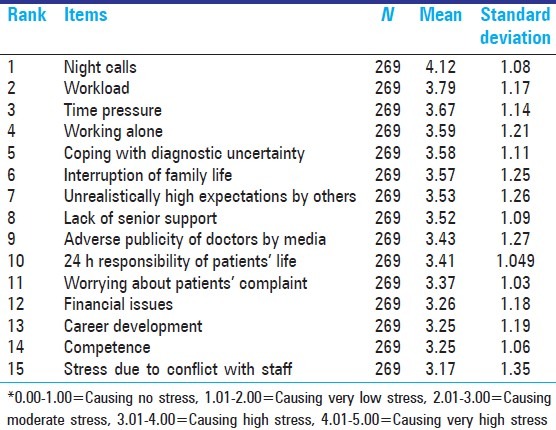

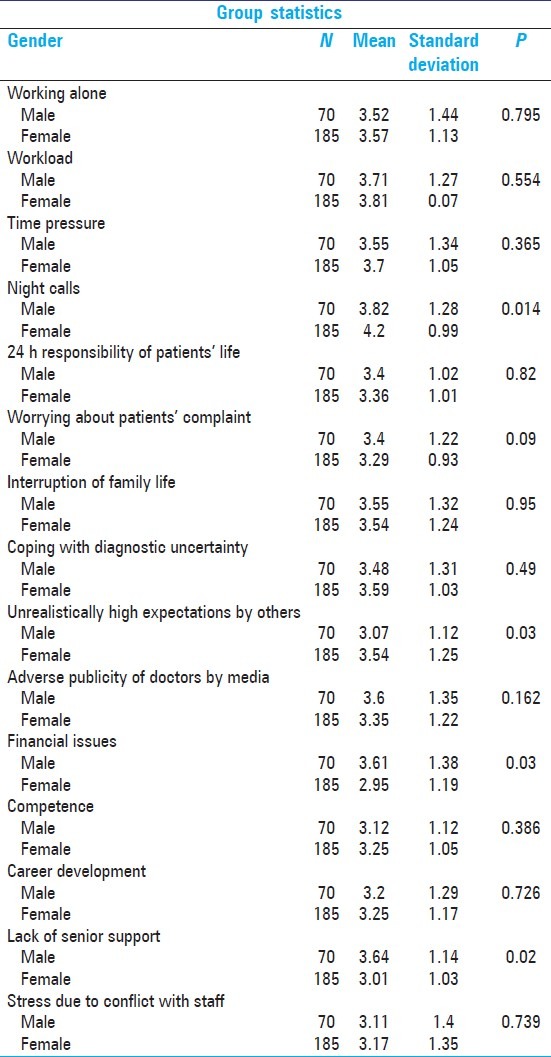

This cross-sectional study was carried out among house officers working in Civil Hospital, Karachi, and Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi, in which 330 house officers were approached out of whom 269 (81.5%) participated. Seventy-seven (28.6%) were males and 192 (71.4%) were females. The mean age was 24.21 (SD = 0.905). Out of 269, 81 (30.2%) house officers had been doing their house job for less than 4 months, 124 (46.3%) house officers had been doing their house job between 4 and 8 months, whereas 63 (23.5%) had been doing their house job for more than 8 months. One hundred twenty-nine (47.9%) were found to be under stress of whom 32 (24.8%) were males and 97 (75.2%) were females [Figure 1]. Nonstressed house officers were 140 (52%) comprising 45 (32.1%) males and 95 (67.9%) females. The mean PSS score in the study population was 28.11 (SD = 5.75) with the median of 28 [Table 1]. House officers who had worked between 4 and 8 months were in most stress (46.1%) compared with other two groups, that is, less than 4 months (30.11%) and more than 8 months (23.42%). The 15-question survey instruments’ sample responses are given in Table 2. Stressors ranked by the house officers are shown in Table 3. Top five were night calls, workload, time pressure, working alone, and coping with diagnostic uncertainty. Among male house officers, night calls, lack of senior support, and workload were major stressors, whereas unrealistically high expectation by others was reported to cause the least stress. Female doctors reported working night calls, workload, and time pressure as the sources causing most stress, whereas the least stress was reported to be financial issues. A significant difference for stressors by gender [Table 3] was found for night calls, unrealistically high expectation by others, financial issues, and lack of senior support (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Stressed and nonstressed male and female house officers

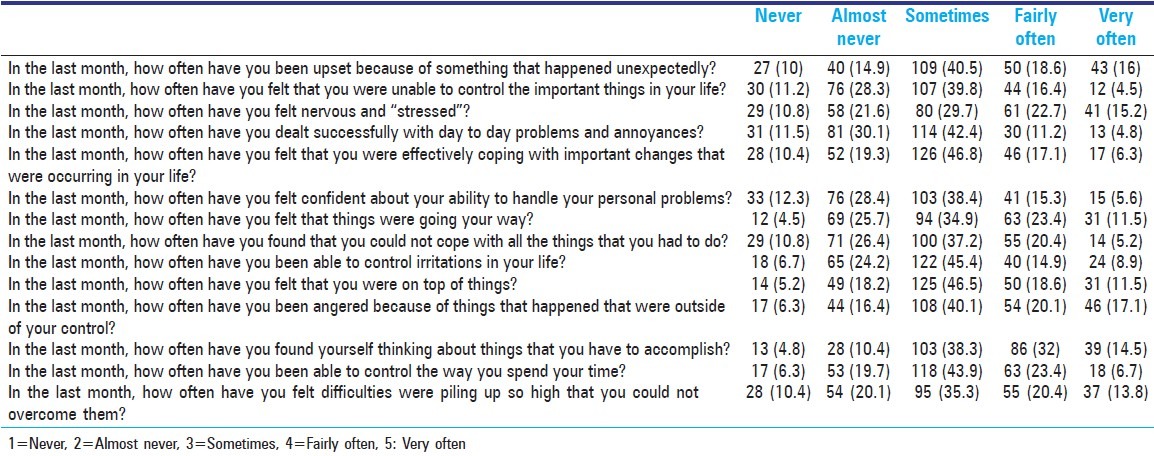

Table 1.

House officers’ responses to the perceived stress scale

Table 2.

Rank of stressors according to the stress intensity perceived by house officers

Table 3.

Mean score and standard deviation of stressors by gender

DISCUSSION

The principal purpose of this study was to investigate perceived stress among house officers and sources of stress, to our knowledge such a detailed study has not been reported from Pakistan. Our findings suggest that close to half of the target population was found to be under stress, which is similar to that found in another study.[6] Three quarters of house officers reported under stress were female. The reason for high stress reported in females might be specific to medical profession, gender, or age.[7] This could also be because of higher number of female doctors being produced by medical schools in Pakistan.

The percentage of house officers under stress is relatively similar to stress prevalence in undergraduate medical students and postgraduate medical trainees as reported in previous studies.[8,9] The similarity was perhaps due to similar medical environment that the groups faced. This alarming finding suggested a sense of growing pressure among doctors. The house officers who had been working for more than 4 months but less than 8 months were more in number, under stress, as compared with the ones who had worked for less than 4 or more than 8 months. A possible explanation to this could be initial euphoria of the new job, which has also been hypothesized by a study as a possible cause of high job satisfaction among young doctors.[10]

We decided to choose the perceived stress scale to asses stress level because this instrument has been documented for its reliability and validity. The advantage of PSS is that it can be applied to a wide range of settings, to different subject types, and includes items measuring reactions to stressful situations as well as measures of stress.[5,11,12,13,14]

Over all, the top five factors that were reported by the participants as the source of stress were night calls, workload, time pressure, working alone, and coping with diagnostic uncertainty. This is in contrast to a study, which tells that 79% doctors come under stress because of high patient volume.[15] Senior's pressure, high expectations, and no appreciation by patients are also among the main sources of stress among doctors.[15] In another study, which was conducted in Malaysia, the major stressors among house officers reported was fear of making mistakes, which can lead to serious consequences, work overload, and working with uncooperative colleagues.[16]

Stressors where female house officers scored significantly lower than male house officers were financial issues and lack of senior support. In our culture where females are mostly dependent on their family or in-laws, staff and doctors are mostly supportive to female doctors. However, stressors for which females scored significantly higher than males were night calls and unrealistic high expectations by others. Because both these hospitals are government-run hospitals where security situation is very poor and house officers usually have to stay in hospital in the night causing them high level of stress.

The limitation of this study is that the findings cannot be generalized to the house officers working in private sector, as only public sector was approached. We cannot rule out the information bias because the information was collected on self-administered questionnaires/instrument. Although response rates (81.5%) were fairly good, there could be some selection (nonresponse) bias. Although participation was anonymous, author and co-authors had the opportunity to meet the nonrespondents and ask them reasons for not participating in the survey. The main reasons that surfaced were the lack of interest and time as well as the length of questionnaire.

CONCLUSION

The themes that have emerged from the study suggest that steps should be taken to eliminate stress at its origin, that is, it should be dealt in terms of preventive rather than curative strategy. Recognizing problem and dealing with them positively is the best step in forward direction. These results imply that focus should be on primary level.

Taking responsibility and making critical decisions is an integral part of a doctor's profession, but it was found on many occasions that these new doctors did not have easy access to senior cover that they had a right to expect. New doctors should be closely supervised in the first few days or weeks in a post and should not be forced to cope with emergencies, ward work, or breaking bad news without a senior accessible for advice and support.

The stresses of excessive intensity of work and night calls are well recognized and this study showed that house officers are still being subjected to both. The tradition of having house officers covering wards at night should be reviewed as much of the work they do could be done by nursing staff, left until morning, or requires a more experienced doctor.

Learning to cope with human tragedy, the limitations of medicine, and their own mortality is hard emotional work even for the most resilient of young doctors, and time should be made available for properly supported discussions in the workplace.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Michie S. Causes and management of stress at work. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:67–72. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro SL, Shapiro DE, Schwartz GE. Stress management in medical education: A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2000;75:748–59. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan KB, Lai G, Ko YC, Boey KW. Work stress among six professional groups: The Singapore experience. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1415–32. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams S, Dale J, Glucksman E, Wellesley A. Senior house officers’ work related stressors, psychological distress, and confidence in performing clinical tasks in accident and emergency: A questionnaire study. BMJ. 1997;314:713–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7082.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall NC, Chipperfield JG, Perry RP, Ruthig JC, Goetz T. Primary and secondary control in academic development: Gender-specific implications for stress and health in college students. 2006;19:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kami R, Amjad S, Delawar K. Occupational Stress and its effects on job performance. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niaz U, Sehar H, Ali S. Stress in women physicians in Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci. 2003;19:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah M, Hassan S, Malik S, Chandrashekhar CT. Perceived Stress, Sources and Severity of Stress among medical undergraduates in a Pakistani Medical School. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sameer-ur-Rehman, Kumar R, Siddiqui N, Shahid Z, Syed S, Kadir M. Stress, job satisfaction and work hours in medical and surgical residency programmes in private sector teaching hospitals of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:1109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madaan N. Job Satisfaction among Doctors in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. JK Science: J Med Educ Res. 2008;10:81. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang EC. Does dispositional optimism moderate the relationship between perceived stress and psychological well-being. A preliminary investigation? Pers Individ Dif. 1998;25:233–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otto MW, Fava M, Penava SJ, Bless E. Life even, mood, and cognitive predictors of perceived stress before and after treatment for major depression. Cogn Ther Res. 1997;21:409–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebrecht M, Hextall J, Kirtley LG, Taylor A, Dyson M, Weinman J. Perceived stress and cortisol levels predicts speed of wound healing in health male adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:798–809. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arya M, Baroda S. Occupational stress among doctor : A case study of PT. B. D. Sharma University Of Health Sciences Rohtak. Int J of Multidisciplinary Res. 2012;2:321–328. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yusoff MS, Jie TY, Esa AR. Stress, Stressors And Coping Strategies Among House Officers In A Malaysian Hospital. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2011;12:85–94. [Google Scholar]