Abstract

A randomized clinical trial of BM vs. blood stem cell transplants from unrelated donors showed that more plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in BM grafts was associated with better post-transplant survival. Here, we describe differences in homing-receptor expression on pDC to explain observed differences following BM vs. blood stem cell transplantation.

Keywords: antigen presenting, chemokine receptor, graft reject, graft vs. host disease, graft vs. leukemia effect, plasmacytoid dendritic cell, stem cell transplantation

Abbreviations: allo-HSCT, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; APC, antigen presenting cell; BDCA, blood dendritic cell antigen; BM, bone marrow; BMTCTN, Bone Marrow Transplantation Clinical Trial Network; CCR, C chemokine receptor; CD, cluster of differentiation; CXCR, CX chemokine receptor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; GVHD, graft vs. host disease; GVL, graft vs. leukemia; HEV, high endothelial venule; HLA-DR, human lymphocyte antigen-DR; IRB, institutional review board; Lin, lineage; PAM, pathogen associated molecular; PB, peripheral blood; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; PRR, pattern recognition receptor

The basis for the success or failure of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) in patients with hematologic malignancies depends mainly upon successful engraftment of donor hematopoietic cells and the reconstitution of a functional immune system. The anticancer effect of allo-HSCT depends mostly on the graft-vs.-leukemia (GvL) effect of donor immune cells that kill chemotherapy-resistant tumor cells. Most of the adverse effects of the allo-HSCT are also immunologic and include graft rejection, opportunistic infections, graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD), and, when the GvL effect fails, relapse. Results of Bone Marrow Transplantation Clinical Trial Network (BMTCTN) 0201 illustrate some interesting new findings related to the role of donor pDC in the graft. BMTCTN0201 was a randomized clinical trial of transplanting either bone marrow (BM) or granulocyte-colony-stimulating-factor (G-CSF) mobilized peripheral blood (PB) stem cell grafts from unrelated donors in patients with hematological malignancies.1 While survival, acute GvHD and relapse were equivalent comparing the two arms, significantly more chronic GvHD occurred among recipients PB stem cell grafts.1 We characterized the immune cells in the transplanted grafts and reported that BM grafts containing more donor pDCs were associated with better survival, and fewer deaths from graft rejection and GvHD, while a similar association of the content of donor pDC in PB grafts with outcomes was not seen.2 These findings suggest that there are immunological differences in pDCs from BM vs. PB grafts, especially in their capacity to induce immune tolerance. Thus we hypothesized that pDCs in BM grafts would have phenotypic differences related to immune function compared with pDC from PB grafts.

In humans, pDCs can be identified by surface expression of BDCA2 or BDCA4,3 or combined expression of HLA-DR and CD123 and the absence of lineage antigens (such as CD3, CD14, CD16, CD19 and CD56) and CD11c.4 Immature pDCs generated from BM precursors are present in low numbers in blood and lymphoid organs, but are rarely detectable in steady state in other tissues.5 Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (including Toll-like receptors 7 and 9) on pDC detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMs) released from the cells killed by chemotherapy/radiation or viral/bacterial pathogens in local sites of inflammation, leading to pDC activation and maturation.6 Mature pDCs up regulate expression of co-stimulating molecules (CD40, CD80 and CD86) and differentiate into effective antigen presenting cells (APC) that activate naïve T cells. Upregulation of homing molecules (CCR7 and L-selectin, CD62L) facilitates targeting of activated pDCs to lymph nodes via high endothelial venules (HEVs) where antigen-presentation occurs.7 Alternatively, activated immature pDC produce high-levels of cytokines, particularly type I interferon, that may modulate innate and adaptive immunity in the setting of transplant-induced inflammation.8 The alternative pathways of pDC maturation are regulated by crosslinking immunoglobulin-like transcript 7, which limits interferon-production and drives pDC toward APC differentiation.9 To understand the immunological basis for differences in outcomes related to donor pDC content of grafts transplanted on BMTCTN0201,2 we tested the hypothesis that pDC from BM and PB grafts differ in their expression of chemokine receptors.

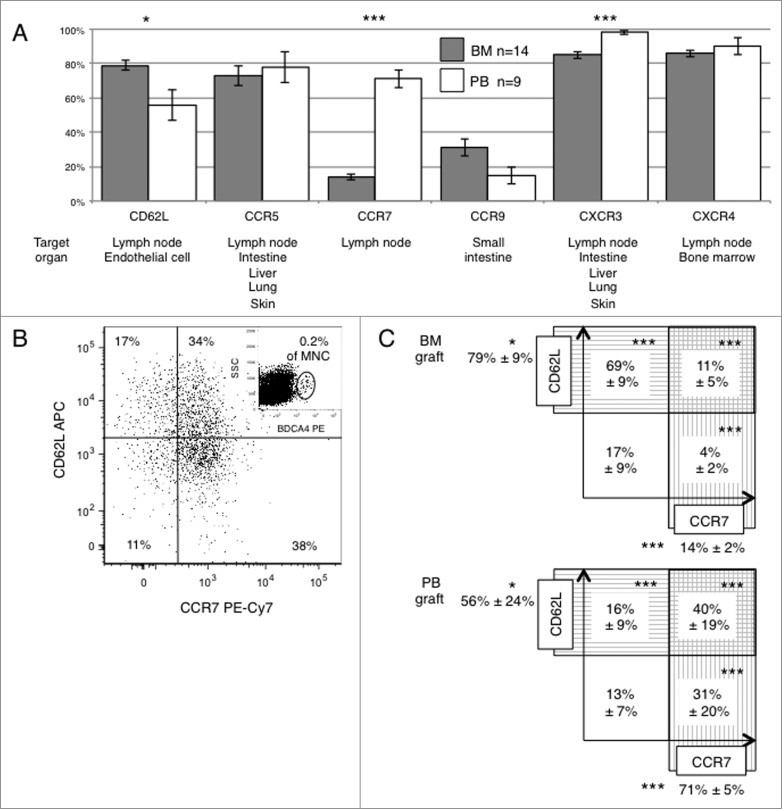

We examined the expression of chemokine/homing receptors in pDCs from fresh BM and PB graft in an IRB-approved study. pDCs were identified based upon expression of BDCA4, a population overlapping with the definition of pDC used in BMTCTN0201 (Lin−HLA-DR+CD11c−CD123+).2 As hypothesized, there were differences in the expression of chemokine and homing receptors between pDC from BM vs. PB grafts, especially in CD62L, CCR7, and CXCR3 (p = 0.017, <0.001 and <0.001, respectively, Fig. 1A). Most pDCs in BM and PB grafts expressed CCR5 (73% and 78% in BM and PB, respectively), CXCR3 (85% and 98%, respectively) and CXCR4 (86% and 90%, respectively), while fewer pDCs expressed CCR9 (31% and 15%, respectively, Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows a representative plot of CCR7 vs. CD62L expression on BDCA4+ pDC from a PB graft. Significant differences in the expression of receptors targeting pDC to lymph nodes were noted, with BM pDC more frequently expressing CD62L (79% vs. 56%, p=0.017), and less frequently expressing CCR7 (14% vs. 71%, P < 0.001), or co-expressing both CCR7+ and CD62L+ (11% vs. 40%, P<0 .001) compared with pDC from PB grafts (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Differences in chemokine and lymph node homing receptors expression on pDCs from BM vs. PB grafts. We examined the expression patterns of chemokine and lymph node homing receptors in pDCs from 14 bone marrow (BM) samples and 9 G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood (PB) stem cell graft samples collected at Emory University from healthy volunteer donors. Eight-color flow cytometry was performed with analysis of fresh graft samples in an IRB-approved protocol. List mode files containing 500,000 events were acquired to determine expression of CXCR3, CXCR4, CCR5, CCR7, CCR9, and CD62L on BDCA4+ pDC within the mononuclear cell population. (A) Comparison of chemokine and lymph node homing receptors expression on pDCs from BM vs. PB grafts. Gray (BM) and white (PB) bars show the mean percentage (± SD) of BDCA4+ pDC expressing each receptor. Target organs that potentially recruit pDCs via expression of the corresponding ligand(s) for each homing/chemokine receptor are listed below. (B) A sample plot of CCR7 vs. CD62L expression on BDCA4+ pDCs in a representative PB graft. The insert in the upper right quadrant shows the gate used to define BDCA4+ pDC. (C) Summary of the mean percentages (± SD) of BDCA4+ pDC expressing CCR7 or CD62L in BM or PB grafts. Asterisks present significant differences comparing mean values from the group of BM vs. PB samples (*<0.05, ***<0.001).

The finding of different patterns of chemokine and lymph node homing receptors on pDC from BM vs. PB grafts helps explain the observation that the content of pDC in BM grafts was associated with overall survival in BMTCTN0201, while the content of pDC in a PB graft was not.2 Of note, pDCs in BM grafts include less mature pDC precursors that have more potential for cytokine production than APC activity, whereas the preponderance of CCR7+ pDCs in PB grafts suggests they are more differentiated. Since co-expression of CD62L and CCR7 is essential to effectively home and migrate into lymph nodes via HEVs, pDCs in PB grafts may be more efficient in activating naïve T cells in lymph nodes, thus increasing risk of GvHD (activation of donor T cells) or graft rejection (activation of host T cells). In contrast, BM pDC are predicted to home to non-lymph node sites, such as BM or inflamed tissues, where they may dampen activation of host and donor T cells. Thus a higher content of donor pDC in BM grafts was associated with fewer deaths from GvHD and graft rejection. Future work will need to identify where and how donor BM pDC exert a tolerogenic effect on donor and host T cells, and how these salubrious properties of donor BM pDC could be recapitulated in hematopoietic progenitor cells harvested from the blood.10

Using donor pDC to optimize GvHD and GvL in allogeneic stem cell transplantation, the goal of this proposed research is to increase understanding of the mechanisms by which donor pDC regulate the allo-reactivity of donor T-cells, which will lead to novel strategies to optimize the content and function of critical immune cells in the stem cell graft.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the NIH/NCI Award Number 1R01CA188523-01A1 (PI: Waller); Andrea and Tim Rollins Award Number 41058 (PI: Waller), a philanthropic award by the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University; Winship Cancer Institute Pilot Award Number 33374 (PI: Waller) and NIH/NCI under Award Number P30CA138292 (PI: Curran); American Society of Hematology ASH Bridge Award Number 23398 (PI: Waller); and Abraham J. & Phyllis Katz Foundation Award Number 29254 (PI: Waller). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, Waller EK, Weisdorf DJ, Wingard JR, Cutler CS, Westervelt P, Woolfrey A, Couban S, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:1487-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waller EK, Logan BR, Harris WA, Devine SM, Porter DL, Mineishi S, McCarty JM, Gonzalez CE, Spitzer TR, Krijanovski OI, et al. Improved survival after transplantation of more donor plasmacytoid dendritic or naive T cells from unrelated-donor marrow grafts: results from BMTCTN 0201. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(22):2365-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dzionek A, Inagaki Y, Okawa K, Nagafune J, Rock J, Sohma Y, Winkels G, Zysk M, Yamaguchi Y, Schmitz J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: from specific surface markers to specific cellular functions. Hum Immunol 2002; 63:1133-48; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0198-8859(02)00752-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collin M, McGovern N, Haniffa M. Human dendritic cell subsets. Immunology 2013; 140:22-30; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/imm.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villadangos JA, Young L. Antigen-presentation properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity 2008; 29:352-61; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2004; 5:987-95; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seth S, Oberdorfer L, Hyde R, Hoff K, Thies V, Worbs T, Schmitz S, Förster R. CCR7essentially contributes to the homing of plasmacytoid dendritic cells to lymph nodes under steady-state as well as inflammatory conditions. J Immunol 2011; 186:3364-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1002598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKenna K, Beignon AS, Bhardwaj N. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: linking innate and adaptive immunity. J Virol 2005; 79:17-27; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/JVI.79.1.17-27.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tavano B, Boasso A. Effect of immunoglobin-like transcript 7 cross-linking on plasmacytoid dendritic cells differentiation into antigen-presenting cells. PLoS One 2014; 9:e89414; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0089414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, Todt L, McGlauchlen K, Fisher N, Devine H, Link DC, Calandra G, Bridger G, et al. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using AMD3100, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood 2008; 112:990-98; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]