Abstract

We have recently demonstrated that pyridoxine, a precursor of vitamin B6, increases the immunogenicity of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) cells succumbing to cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), CDDP). Accordingly, pyridoxine promoted the antineoplastic activity of CDDP in NSCLC-bearing mice only in the presence of an intact immune system. These findings may have implications for the development of novel strategies to circumvent CDDP resistance.

Keywords: apoptosis, ATP, autophagy, calreticulin, endoplasmic reticulum stress, HMGB1, PDXK

Abbreviations: CDDP, cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II); NSCLC, non-small cell lung carcinoma; PDXK, pyridoxal kinase; PN, pyridoxine

Platinum derivatives including cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), CDDP), oxaliplatin and carboplatin are currently employed for the treatment of several neoplasms.1 For hitherto unclear reasons, CDDP is associated with a high rate of durable responses only among testicular cancer patients. Conversely, the long-term therapeutic benefits of CDDP for individuals with lung, colorectal, prostate or ovarian carcinomas are limited. This is mainly due to the fact that a large fraction of neoplasms that are initially sensitive to CDDP become resistant over time, eventually resulting in disease relapse and therapeutic failure.1 Throughout the past decades, great efforts have been dedicated to the development of therapeutic interventions that would restore (at least in part) CDDP sensitivity.2 In spite of promising preclinical results, however, none of this approaches has been translated into the clinical practice. Thus, acquired CDDP resistance constitutes a hitherto unsolved medical issue.

The decreased susceptibility of neoplastic cells CDDP is rarely unifactorial, meaning that it generally stems from multiple, non-overlapping alterations.2,3 Moreover, unlike their oxaliplatin-treated counterparts, cancer cells exposed to CDDP are unable to elicit an adaptive immune response upon inoculation into immunocompetent hosts.4,5 These observations might explain why efficient strategies for reverting CDDP resistance in clinical settings have not yet been developed.

We previously reported that vitamin B6 has a significant influence on the response of transformed cells to a variety of physical, chemical, and metabolic insults.6,7 Thus, the administration of pyridoxine (PN), a cell-permeant precursor of the active form of vitamin B6 (i.e., pyridoxal-5-phosphate), sensitizes cancer cells of various histological origin to the cytotoxic effects of multiple chemotherapeutics (including CDDP), irradiation, hyperthermia, nutrient deprivation, and hypoxia, just to mention a few examples. Notably, such an effect strictly depends on the presence of pyridoxal kinase (PDXK), the enzyme that phosphorylates vitamin B6 precursors to synthesize pyridoxal-5-phosphate. In line with a key role for vitamin B6 metabolism in the demise of malignant cells exposed to adverse micro-environmental conditions, we also found that high expression levels of PDXK (as measured by immunohistochemistry in tumor biopsies) positively influence disease outcome in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, irrespective of whether they are treated or not.6 The molecular mechanisms whereby PN sensitizes cancer cells to the cytotoxic potential of various chemical, physical and metabolic insults remain to be precisely determined, but may relate to an accrued oxidative response.6 In the specific case of CDDP, the chemosensitizing effects of PN also reflect an increased intracellular accumulation of the drug that depends on PDXK1 but not on known CDDP transporters such as solute carrier family 31, member 1 (SLC31A1, best known as CTR1) and ATPase, Cu2+ transporting, β polypeptide (ATP7B).8

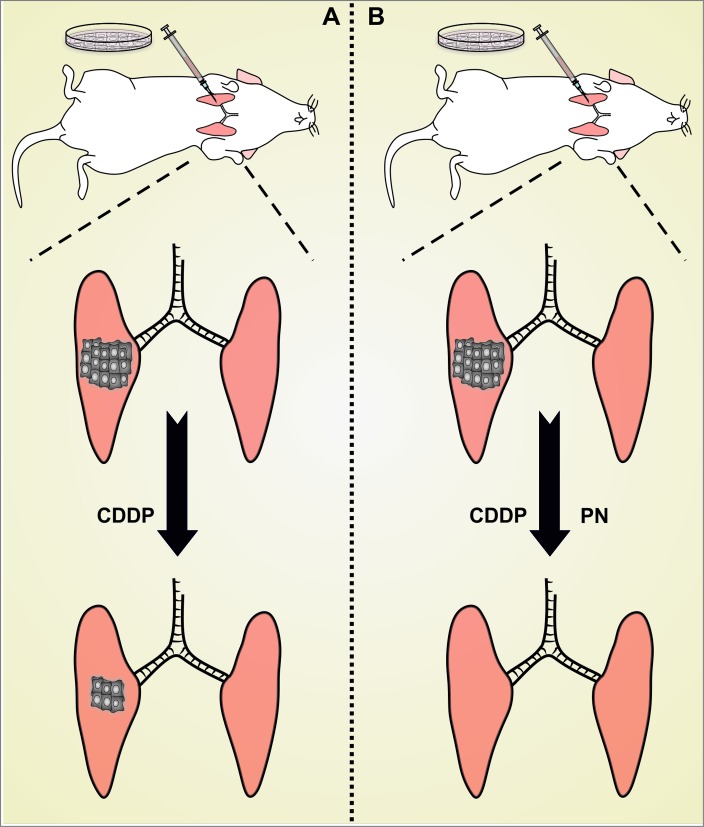

We have recently demonstrated that the ability of PN to improve the therapeutic profile of CDDP involves not only cancer cell-intrinsic mechanisms but also immunological circuitries (Fig. 1).9 In particular, we showed that a non-toxic amount of PN not only synergizes with a suboptimal dose of CDDP in the killing of murine Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) cells, but also renders their demise immunogenic, as demonstrated in gold-standard vaccination assays involving syngeneic C57BL/6 mice. In line with notion, LLC cells responding to CDDP plus PN, but less so cells exposed to either agent alone, manifest several hallmarks of immunogenic cell death (ICD),5 including the inactivating phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2A (EIF2A), the exposure of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone calreticulin (CALR) on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, the secretion of ATP, and the release of the non-histone chromatin-binding protein high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1). Moreover, the combination of CDDP and PN exerts superior antineoplastic activity against luciferase-expressing NSCLCs established orthotopically as compared to either agent alone, a synergistic effect that is completely abolished in athymic nu/nu mice, which lack T cells (and hence suffer from a lack of cell-mediated immunity). Lending further support to the notion that PN renders CDDP-induced cell death immunogenic, mice in which the administration of CDDP plus PN causes complete and durable tumor regression (approximately 45%, in our hands) are completely protected from a subsequent challenge with living cancer cells of the same type, but not from the inoculation of unrelated cancer cells.9

Figure 1.

Impact of vitamin B6 on the immunogenicity of cisplatin-induced cell death. (A) In most circumstances, cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II), CDDP) employed as a standalone therapeutic intervention kills neoplastic cells in an immunologically silent fashion. In other words, cancer cells dying upon exposure to CDDP fail to elicit a therapeutically relevant adaptive immune response against dead cell-associated antigens. (B) In the presence of pyridoxine (PN), malignant cells succumb to CDDP while emitting a spatiotemporally defined combination of damage-associated molecular patterns with potent immunostimulatory effects. Thus, PN appears to efficiently convert the immunologically silent demise of cancer cells exposed to CDDP into bona fide immunogenic cell death (ICD).

These findings may have important implications for the development of novel strategies to circumvent CDDP resistance. Indeed, in our preclinical models, the administration of PN along with CDDP-based chemotherapy increases not only the fraction of malignant cells succumbing to treatment, but also their ability to initiate a tumor-targeting adaptive immune response. PN may therefore shift the therapeutic activity of CDDP toward that of oxaliplatin, which is per se able to cause ICD.4,5 It remains to be formally demonstrated whether such shift also occurs in the human system, in which gold-standard vaccination assays for the detection of ICD are not yet feasible. If this were the case, combinatorial regimens involving CDDP and PN may turn out to resemble clinically successful chemotherapeutics such as gemcitabine and cyclophosphamide in their ability to kill cancer cells while eliciting novel or boosting pre-existent anticancer immune responses.10 Irrespective of this possibility, properly designed clinical trials are required to assess the actual therapeutic benefits of PN of other B6 vitamers in the course of platinum-base chemotherapy.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

Authors are supported by the Ligue contre le Cancer (équipe labelisée); Agence National de la Recherche (ANR); Association pour la recherche sur le cancer (ARC); Cancéropôle Ile-de-France; Institut National du Cancer (INCa); Fondation Bettencourt-Schueller; Fondation de France; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM); the European Commission (ArtForce); the European Research Council (ERC); the LabEx Immuno-Oncology; the SIRIC Stratified Oncology Cell DNA Repair and Tumor Immune Elimination (SOCRATE); the SIRIC Cancer Research and Personalized Medicine (CARPEM); and the Paris Alliance of Cancer Research Institutes (PACRI).

References

- 1. Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2007; 7:573-84; PMID: ; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrc2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galluzzi L, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Michels J, Martins I, Kepp O, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene 2012; 31:1869-83; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2011.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Michels J, Brenner C, Szabadkai G, Harel-Bellan A, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Systems biology of cisplatin resistance: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2014; 5:e1257; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2013.428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martins I, Kepp O, Schlemmer F, Adjemian S, Tailler M, Shen S, Michaud M, Menger L, Gdoura A, Tajeddine N, et al. Restoration of the immunogenicity of cisplatin-induced cancer cell death by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Oncogene 2011; 30:1147-58; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2010.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Zitvogel L. Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:51-72; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Senovilla L, Olaussen KA, Pinna G, Eisenberg T, Goubar A, Martins I, Michels J, Kratassiouk G, et al. Prognostic impact of vitamin B6 metabolism in lung cancer. Cell Rep 2012; 2:257-69; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galluzzi L, Vacchelli E, Michels J, Garcia P, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Vitale I, Kroemer G. Effects of vitamin B6 metabolism on oncogenesis, tumor progression and therapeutic responses. Oncogene 2013; 32:4995-5004; PMID: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Galluzzi L, Marsili S, Vitale I, Senovilla L, Michels J, Garcia P, Vacchelli E, Chatelut E, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Vitamin B6 metabolism influences the intracellular accumulation of cisplatin. Cell Cycle 2013; 12:417-21; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/cc.23275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aranda F, Bloy N, Pesquet J, Chaba K, Sauvat A, Kepp O, Khadra N, Enot D, Pfirschke C, Pittet M, et al. Immune-dependent antineoplastic effects of cisplatin plus pyridoxine in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2014; in press; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2014.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Mechanism of action of conventional and targeted anticancer therapies: reinstating immunosurveillance. Immunity 2013; 39:74-88; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]