Abstract

Considerable efforts have been invested to understand the mechanisms by which pro-inflammatory cytokines mediate the demise of β-cells in type 1 diabetes but much less attention has been paid to the role of anti-inflammatory cytokines as potential cytoprotective agents in these cells. Despite this, there is increasing evidence that anti-inflammatory molecules such as interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10 and IL-13 can exert a direct influence of β-cell function and viability and that the circulating levels of these cytokines may be reduced in type 1 diabetes. Thus, it seems possible that targeting of anti-inflammatory pathways might offer therapeutic potential in this disease. In the present review, we consider the evidence implicating IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 as cytoprotective agents in the β-cell and discuss the receptor components and downstream signaling pathways that mediate these effects.

Keywords: interleukin-4, interleukin-10, interleukin-13, type 1 diabetes, STAT3, STAT6

Abbreviations

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- IL

interleukin

- Jak

janus kinase

- NO

nitric oxide

- PTP

protein tyrosine phosphatase

- SOCS

suppressor of cytokine signaling

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- Th

T-helper

Introduction

Human type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by islet inflammation (“insulitis”) and the subsequent selective destruction of pancreatic β-cells. The triggering factors have yet to be elucidated in full but it is well-established that genetic predisposition plays an important role. However, the rate at which T1D is increasing among young people in many Western countries implies that genetic factors cannot be solely responsible and that an environmental trigger also exists. A number of candidates have been suggested (e.g. cow's milk, gluten), however the strongest link implies the involvement of one or more viruses; most notably enteroviruses.1-4 In this model, it is hypothesized that an initial (acute) viral infection of the β-cells may lead, secondarily, to the establishment of a more sustained infection in which the β-cells survive but have altered properties such that they display islet antigens inappropriately. This then promotes autoimmunity and initiates the insulitic attack.5

Few studies have characterized the insulitic lesions fully in human pancreas but it is accepted that CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, CD4+ T-helper (Th) cells, B-cells and macrophages are all present.6-8 These secrete an array of pro-inflammatory cytokines and in vitro studies have shown that such molecules can induce apoptosis in rodent and human β-cells,9-11 thereby providing one mechanism by which β-cell death might ensue. However, an increased generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines may not be the sole factor that drives β-cell demise since a concomitant loss of anti-inflammatory cytokine signaling could also contribute.

Anti-inflammatory cytokines are broadly antagonistic to their pro-inflammatory counterparts and are able to diminish inflammatory responses and to protect cells from otherwise cytotoxic insults. The importance of anti-inflammatory cytokines in protecting β-cells is still open to debate although there is evidence that the production of these molecules may be reduced in type 1 diabetes.12-15 If this is also the case within the islet milieu, then this would tend to exacerbate any detrimental effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In the present review, we assess the current understanding of the effects of anti-inflammatory cytokines on the pancreatic β-cell, specifically focusing on 3 key molecules (IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10) which have been implicated in the control of β-cell viability. We note that other immune factors with anti-inflammatory properties may also be important in control of β-cell function (e.g., TGF-β, sIL-1ra, IL-11 and IL-35) and that the actions of some of these molecules have been reviewed elsewhere.16,17

Anti-inflammatory Cytokines and Type 1 Diabetes

Anti-inflammatory cytokines are secreted by a number of immune cell subtypes including CD4+ Th2 cells, regulatory T cells, M2 macrophages, mast cells and regulatory B-cells. Many of these have been implicated as mediators of beneficial responses in the context of type 1 diabetes although most emphasis has been placed on the influence of T-helper and T-regulatory cells. For example, it is suggested that during the pathogenesis of human type 1 diabetes, a polarization of CD4+ T-helper cells occurs, leading to a predominance of the Th1 phenotype with a concomitant down-regulation of the Th2 response.18,19 Under such conditions, PBMCs isolated from the blood of T1D patients (or their first degree relatives) exhibit a reduction in anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion when compared to healthy controls.12-15 The significance of this switch has been emphasized by the demonstration that administration of a cocktail of cytokines secreted from Th2 cells (including IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13) was protective against diabetes progression in rodents. Hence, numerous studies have revealed that treatment of NOD mice (a rodent model of type 1 diabetes) with IL-4, IL-13 or IL-10 delays the onset of spontaneous diabetes and also reduces its incidence.20-24 Furthermore, T-cells isolated from the blood of such mice exhibit a more Th2-like phenotype, releasing higher levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines than those of control NOD mice.22,25 The incidence of diabetes can also be delayed in the NOD mouse by generating animals that specifically express IL-4 in β-cells26 or by the injection of dendritic cells which constitutively express this cytokine27 However, other studies have found that overexpression of IL-10 in islet endocrine cells may have little effect on diabetes progression,28 and in some cases it can accelerate the disease process.29 This paradoxical effect may be explained by differences in factors such as the local concentration and localization of IL-10 between the study designs,30 and highlights the complexity in the function of these cytokines in diabetes. Given the body of evidence above, it may be significant for disease pathogenesis, that in situ RT-PCR analysis has revealed that anti-inflammatory cytokines are expressed at only low levels in the immune cell infiltrates of 4 rodent models (NOD mouse, BB rat, Komeda rat, LEW.1AR1-iddm rat) and in human patients with type 1 diabetes.31

While many of their beneficial effects undoubtedly stem from the anti-inflammatory impact of the molecules on various immune cells, it is also evident that such cytokines can also exert a positive impact on the islet cells directly. Importantly, isolated islets are a heterogeneous group of cells which contain resident immune cells, endocrine cells and possibly other cell types. Thus careful interpretation of results is required when examining data from isolated islets. That said, treatment of human islets or clonal β-cell lines with IL-4, IL-13 or IL-10 protects against a variety of cytotoxic insults.9,32-35 Furthermore, additional data have revealed that these cytokines can also reverse the detrimental effects of some pro-inflammatory mediators on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in both clonal β-cells and primary islets.9,36 Evidence also points toward a potential pro-proliferative role for certain anti-inflammatory cytokines on islet cells. In these experiments, adoptive transfer of various T-cell populations led to an increase in β-cell proliferation through the secretion of soluble factors including IL-10.37 Finally, anti-inflammatory molecules are reported to inhibit changes in the microvasculature associated with diabetes progression in the NOD mouse.24 Taken together, it can be concluded from such evidence that, while pro-inflammatory factors are likely to be of primary importance in diabetes pathogenesis, any simultaneous reduction in the level of anti-inflammatory cytokines may serve to exacerbate their negative effects on islet cell viability and function.

IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10

IL-4 and IL-13 are distantly related multifunctional cytokines which are encoded by genes located in a cytokine gene cluster on human chromosome 5 at region 5q31. In humans these 2 molcules share approximately 30% protein sequence homology and they also display clear similarities in secondary structure. IL-4 (∼17 kDa) and IL-13 (∼16 kDa) share a cognate cell surface receptor and they induce similar (but not identical) downstream signaling cascades. By contrast, the gene encoding IL-10 is structurally distinct and is located on human chromosome 1 at 1q31-32. It is comprised of 5 exons, and generates a protein of approximately 18 kDa. IL-10 signals via a unique set of receptor components which are not shared with IL-4 or IL-13.

In a wider functional context, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 are known to promote humoral immunity and to exert profound and diverse anti-inflammatory effects including inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine production, promotion of the differentiation of naïve T-cells toward a Th2 phenotype and increased expression of various anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic genes (e.g. heme oxygenase-1, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and survivin) in target cells. Despite these positive effects, anti-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-13, are also implicated in some pathological conditions. As an example, they are important mediators of allergic airway responses where they induce the production of allergy associated chemokines, mucus hypersecretion, immunoglobulin class switching to IgG and IgE, airway hyper responsiveness and fibrosis.38

Although, as stated previously, cytokines originate most commonly from cells with an immune origin, islet endocrine cells may also be a potential source. Thus, various cytokines are synthesized and released from islet cells, including IL-1β, IL-6, IFNγ and IL-12.39-41 The capacity of islet cells to generate anti-inflammatory cytokines has been less well-studied but there is evidence that they may be elaborated from islet cells under some circumstances. Thus, with the recent interest in the possibility of a viral trigger for type 1 diabetes, several studies have set out to identify genes which show altered expression in response to a viral challenge. Intriguingly, 2 studies have reported an elevation of IL-10 mRNA and protein production from isolated human islets following infection with an enterovirus2,42 although, in a third study, no increase was detected.43 Immunological evidence deposited in the human protein atlas (www.proteinatlas.org; last accessed 11/04/14) also suggests that certain islet cells stain very intensely for IL-10, implying that it may be produced within these cells. Additionally, it was found that IL-13 can also be generated in human islets and that its production is down-regulated during viral infection.42 By contrast, human islets may not be a source of IL-4 since levels of this cytokine were below the limits of detection in 2 studies.2,43 Despite this evidence, it is not yet clear which specific cell types within the islets are responsible for cytokine release. In addition, the underlying mechanisms mediating the synthesis and release of cytokines from islet cells also require examination. Overall, these data show that, under appropriate conditions, islet cells have the capacity to synthesize, release and respond to various anti-inflammatory cytokines and this concept then opens up the possibility that under relevant conditions, anti-inflammatory cytokine signaling in islets may be regulated in an immune cell independent autocrine or paracrine manner. However, it cannot be excluded that resident immune cells within the islet might also contribute to the release of these factors. In either case, it is possible that anti-inflammatory cytokines produced from the islet may offer a level of protection in the face of local stressors under a variety of (patho)physiological conditions.

Anti-inflammatory Cytokine Receptor Expression in Islet Cells

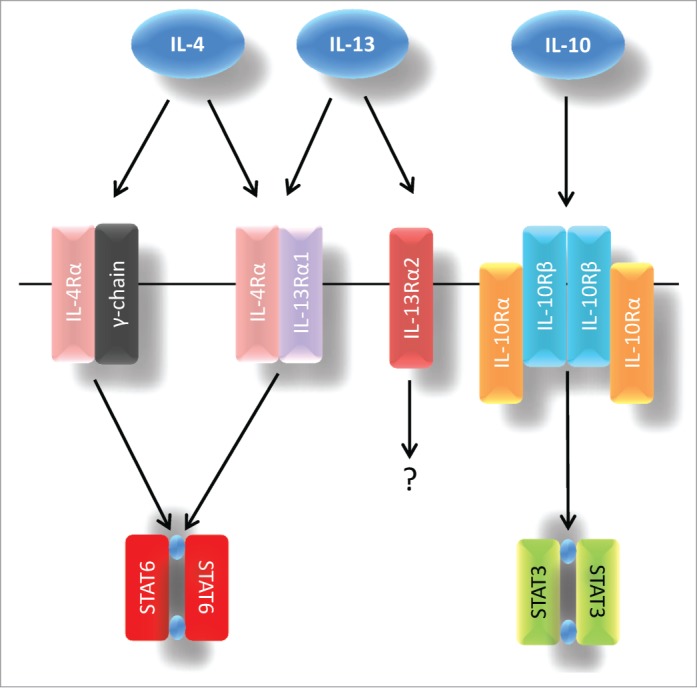

Classically, cytokines induce their biological effects by binding to cognate cell surface receptors which then initiate relevant intracellular signal transduction cascades. The receptor subunits responsible for eliciting the effects of IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10 are depicted in Figure 1. IL-4 and IL-13 are known to be capable of binding to at least one common component, although other receptor subunits have been identified which bind these cytokines individually.44,45 IL-4 binds to the IL-4Rα subunit, and upon cytokine binding, this molecule then recruits either the IL-13Rα1 subunit or the common γ-chain (which is also capable of forming complexes with a host of other cytokine receptors including IL-2Rα, IL-7Rα or IL-21R) to form a functional receptor. IL-13 can bind to the IL-13Rα1 subunit (which then dimerizes with IL-4Rα) or to an IL-13Rα2 monomer which has been described as a decoy receptor because of its short cytoplasmic tail (although a potential signaling role for this receptor has recently been described).46 IL-10, on the other hand, interacts with a completely different set of receptor components, consisting of the IL-10Rα and IL-10Rβ subunits.47 Two molecules of each subunit are recruited to form a heterotetrameric functional receptor. Although IL-10Rα plays a unique role in IL-10 signaling, IL-10Rβ may also interact with additional receptor subunits to facilitate signal transduction induced by molecules such as IL-22, IL-26, IL-28 and IL-29.48 Thus, there is considerable promiscuity among cytokine receptor components and the precise combinations that are assembled under any given circumstance may dictate which responses ensue.

Figure 1.

Canonical signal transduction via IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10 receptors. IL-4 interacts with either the IL-4Rα/common γ-chain or the IL-4Rα/IL-13α1 receptor complexes, whereas IL-13 binds to an IL-4Rα/IL-13α1 dimer or to an IL-13α2 monomer. IL-10 signals via IL-10Rα/IL-10Rβ. IL-4 and IL-13 are known to preferentially induce STAT6 signaling while IL-10 responses are usually mediated via STAT3.

Few studies have examined the expression of the cognate receptors for IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10 in primary islet cells and much of the current information comes from rodent islet cell lines (Table 1). mRNA encoding IL-4Rα, IL-13Rα1 and the common γ-chain was detected in BRIN-BD11 cells, and expression of these receptor subunits was also reported at the protein level in these cells by ICC.33 In a separate study, IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 mRNA expression were found in INS-1E cells32 and, importantly, in the same study, both IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 mRNA were also detected in isolated human islets. Furthermore, IHC analysis of normal adult pancreas revealed the presence of IL-4Rα throughout the islet.34 These data suggest that IL-4Rα is expressed in β-cells (and possibly also in other islet endocrine cells) although this still requires more complete confirmation.

Table 1.

Anti-inflammatory receptor component expression in primary islet cells and islet cell lines

| Receptor Subunit | Cell/Tissue | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| IL-4Rα | Human islets | RT-PCR, ICC (32, 33) |

| INS-1E cells | RT-PCR (32) | |

| BRIN-BD11 cells | RT-PCR, ICC (33) | |

| IL-13Rα1 | Human islets | RT-PCR (32) |

| INS-1E cells | RT-PCR (32) | |

| BRIN-BD11 cells | RT-PCR, ICC (33) | |

| IL-13Rα2 | Rodent islets | qPCR (49) |

| IL-10Rα | Human Islets | RT-PCR (Fig. 2) |

| IL-10Rβ | Human α and β cells | IHC (52) |

| Human islets | RT-PCR (Fig. 2, 52) | |

| INS-1E cells | RT-PCR (Fig. 2) |

IL-13Rα2 is known to be expressed in the pancreatic islets of rodents, and high fat diet treatment of these animals induced an elevation in the mRNA encoding this subunit.49 In other systems, elevated IL-13Rα2 expression derives from stimulation with various cytokines, including TNFα,50 suggesting that it may be subject to acute regulation according to the cellular milieu. IL-13Rα2 has a higher affinity for IL-13 than does IL-13Rα1 and, as a consequence, increased expression of IL-13Rα2 might lead to reduced signaling through the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα receptor complex,51 and thereby dampen any anti-inflammatory effects mediated through IL-13Rα1. It might be speculated, therefore, that if an elevation of IL-13Rα2 occurred in the islet β-cells in diabetes, this could increase their vulnerability to apoptosis; a possibility that warrants further investigation.

IL-10Rβ expression has been studied recently in human islets in the context of IFNλ (IL-28) production by the endocrine cells in response to Coxsackievirus infection52 since this component can also form part of the IL-28 receptor. Healthy human pancreatic islets were shown to express IL-10Rβ at the mRNA level and further investigation by IHC revealed that this receptor subunit is present in both α- and β-cells, but absent from δ-cells.37 We have studied the expression of IL-10 receptor subunits in INS-1E cells and in isolated human islets by RT-PCR (Fig. 2) and have confirmed that IL-10Rα and -β are each expressed in human islets, although we were unable to detect IL-10Rα in INS-1E cells. This might imply that IL-10Rα is not found in β-cells or, more cautiously, it could simply mean that INS-1E cells are not an ideal model in which to study IL-10 signaling. Further experiments are required to firmly establish the pattern of IL-10Rα expression in rodent and human islet cells.

Figure 2.

IL-10 receptor components are expressed in pancreatic endocrine cells. The expression of IL-10Rα and IL-10Rβ was examined by RT-PCR in cDNA generated from human islets and INS-1E cells. Amplified products were separated on agarose gels and examined under UV illumination after staining with Gel Red. Arrows indicate the position of the 300bp marker. To confirm their identity, bands were extracted and sequenced. Primer pairs used for PCR analysis were: IL-10Rα (human) Fd: ATGACCTTACCGCAGTGACC Rv: TCCAGAGGTTAGGAGGCTGA, IL-10Rβ (human) Fd: CTCGGCTGCTTCGCCTTGCT Rv: CTAGCTTTGGGGCCCCTGCC, IL-10Rα (rat) Fd: CCTGCATGGCAGCACCGACA Rv: ACAACCATGGCCCAAGGCGG, IL-10Rβ (rat) Fd: CCCTCCCTGGATCGTGGCCA Rv: AGCTCCTGAGGCCCTGCCTC.

A number of naturally occurring polymorphisms have been identified within the genes encoding IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10, their respective receptor subunits, as well as in components of their downstream signaling cascades. Many of these have been associated with allergic or inflammatory disorders,53 although certain studies have also linked SNPs in some of the genes (or specific inherited haplotypes) to diabetes risk. Indeed, a number of relatively small-sized studies have reported an association between SNPs within IL-4R, IL-4 and IL-13 and type 1 diabetes risk.54-56 However, others have not confirmed this association,57 and one larger study revealed an association between IL-4R SNPs and T1D in only a single cohort among the type 1 diabetes genetics consortium collection.58 In this case, the authors mooted the idea that their own association data and those obtained elsewhere might be false positives. Nevertheless, they did not go as far as to draw the firm conclusion that SNPs within the IL-4R are not associated with T1D susceptibility. Genes encoding the IL-10 receptor components have not been linked to diabetes risk, however recent data has linked a SNP in the promoter of the IL-10 gene itself to risk of type 2 diabetes or to gestational diabetes.59

Signal Transduction Pathways Activated by Anti-inflammatory Cytokines in Islet Cells

The canonical intracellular signaling pathways deriving from treatment of cells with IL-13, IL-4 or IL-10 have been reviewed elsewhere,44,45,47,60 and will not be described in detail here. Briefly, however, it is thought that binding of IL-13, IL-4 or IL-10 to their cognate receptors leads to the formation of functional protein complexes in the plasma membrane. Members of the Janus kinase (Jak) family of proteins are associated with each receptor constitutively and these become trans-phosphorylated (and activated) in response to formation of the active complex. Active Jaks then phosphorylate key tyrosine residues on the cytoplasmic tail of the cytokine receptor with which they are associated. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) family monomers are recruited to the phosphorylated residues by virtue of an interaction with their C-terminal SH2 domains. Classically, IL-4 or IL-13 are considered to recruit STAT6, whereas IL-10 usually signals via STAT3.

Once bound to the receptor, the STAT protein is, itself, phosphorylated on target tyrosine residues by activated Jak, thereby facilitating the disengagement of STATs from the receptor. Upon release, STAT molecules dimerize (and/or possibly form larger oligomeric complexes) with other phosphorylated STATs and translocate to the nucleus where they bind to consensus sequences present within defined target genes to promote transcription.

In addition to activation of the Jak/STATs, other pathways have also been implicated in cytokine receptor signaling, with the best-studied of these being the PI-3K/Akt pathway. In this case, IRS1 or IRS2 is recruited to the tyrosine phosphorylated cytoplasmic tail of the cytokine receptor where it becomes phosphorylated by Jak. The phosphorylated IRS protein then binds to the regulatory p85 subunit of PtdIns-3K which liberates the catalytic p110 subunit to catalyze the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5) trisphosphate (PIP3). Serine/threonine kinases, such as PDK and Akt, are then recruited to the newly formed PIP3 molecules via their PH domains and this association leads to an initial threonine phosphorylation of Akt by PDK, which precedes full Akt activation and the initiation of subsequent downstream signaling events.61 Additional pathways activated in response to IL-4 or IL-13 include MEK/ERK1/2 and the induction of TGF-β via the IL-13Ra2-dependent stimulation of AP-1; however these have not yet been examined in β-cells.44,46

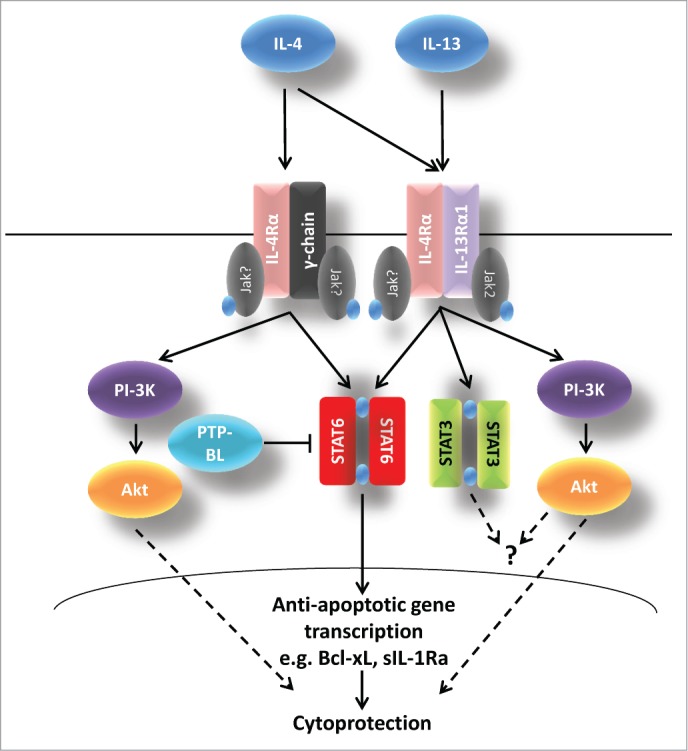

In pancreatic β-cells the downstream signaling events that follow from anti-inflammatory cytokine receptor activation have received only limited investigation and IL-10 signaling is still largely unexplored. In BRIN-BD11 cells, IL-4 treatment increased the phosphorylation of STAT6 and Akt.34 Similarly, IL-13 was shown to increase the levels of pJak2, pSTAT3 and pSTAT6.32 Importantly, in the same report, elevations in pSTAT3 and pSTAT6 were also confirmed in IL-13 treated human islets. Deployment of a pan-Jak inhibitor (pyridine 6) dose-dependently reduced the IL-13 mediated phosphorylation of STAT6 and STAT3 in rodent β-cells, confirming that these effects are Jak dependent.32 Surprisingly, however, the complement of Jaks expressed in β-cells has not been established, and it is not yet clear which Jak isoform(s) is responsible for mediating these effects, although Jak2 may play a role.32 Taken together, these data obtained in islet cells are consistent with the canonical model of IL-4/13 signaling seen in other cell types.45 Figure 3 illustrates the current understanding of IL-4/13 signaling in pancreatic β-cells based on the knowledge gained from such studies.

Figure 3.

Possible pathways of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling in pancreatic β-cells. Following interaction of IL-4 with its cognate receptors, Jak kinases are phosphorylated. This leads to the recruitment and activation of STAT6 and to activation of the PtdIns-3K/Akt pathway. IL-13 also activates both the STAT6 and PI-3K/Akt pathways but there is evidence that STAT3 may also become phosphorylated. IL-4 and IL-13 induced cytoprotection is probably mediated via STAT6 and the extent of phosphorylation of this molecule is also regulated by PTP-BL. The functional consequences of IL-13-induced STAT3 phosphorylation are unclear. In addition, the increase in Akt phosphorylation mediated by IL-13 is not obligatory for cytoprotection.

One intriguing observation was the (very unexpected) detection of 3 separate protein bands on Western blots when INS-1E cell lysates were probed with antisera directed against pSTAT632 following exposure to anti-inflammatory cytokines. One of these migrated at the expected molecular weight of native pSTAT6 (105kDa) whereas the 2 additional bands ran more slowly. None was present in lysates recovered from unstimulated cells but all 3 were induced in response to either IL-4 or IL-13. A similar pattern was observed in BRIN-BD11 cells and in the human β-cell line, 1.1B4 upon exposure to IL-13, whereas only a single band was found in extracts of human islets exposed to IL-13. The precise identity of the slowly-migrating (higher molecular weight) bands seen in the cell lines has not been established but they do not appear to represent any of the previously described STAT6 isoforms since these are of lower molecular weight than the native protein.62 It seems probable that the novel bands must all contain a residue equivalent to the Tyr at position 641 in native STAT6 since this forms the target site for Jak-mediated phosphorylation and the phospho-specific antiserum employed in the studies detects an epitope which encompasses phospho-Tyr641. Conceivably, the variants may represent forms of STAT6 that are post-translationally modified, leading to their altered migration characteristics on SDS gels. In support of this, STAT6 is known to undergo a range of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation (serine and tyrosine), methylation, acetylation, sumoylation and O-linked N-acetylglucosaminylation. Many of these modifications have significant effects on STAT6 function62 and they may contribute to differences in the overall profile of biological effects elicited but it remains unclear why and how these unusual forms of STAT6 are generated in cytokine-treated β-cells.

Cytokine signaling can be negatively regulated by a number of molecules including members of the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family and various tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). A number of PTPs, including PTP-BL and PTPN2 (TCPTP), are reportedly expressed in rodent β-cells63,64 and STAT6 has been identified among their substrates.65,66 In INS-1E cells, over-expression of PTP-BL abrogated the phosphorylation of STAT6 after IL-4 treatment.34 SNPs associated with the gene encoding PTPN2 have been identified as pre-disposing to Type 1 diabetes,67 and knockdown of PTPN2 in INS-1 cells enhances the toxicity of pro-inflammatory cytokines.68 These data highlight the probable importance of the Jak/STAT pathway in the pathogenesis of diabetes and emphasize the potential involvement of anti-inflammatory cytokines.

The culmination of downstream signaling events in cells exposed to IL-4, IL-13 and IL-10 is a change in target gene expression. While this change often results in an increased expression of the target gene, STAT-dependent negative regulation of some genes has also been described,69 Examples of reportedly STAT6 responsive genes include those encoding proteins involved in regulation of cell viability (such as Bcl-xL or sIL-1ra) as well as receptor components driving cytokine responses, such as IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα2.69-71 By contrast, STAT3-induced genes include c-Myc, c-Fos and SOCS3.72,73 The expression of STAT3- and STAT6-responsive genes in β-cells following anti-inflammatory cytokine treatment remains almost completely unexplored, and the understanding of which genes (and their products) are altered in response to these molecules will provide important mechanistic insights into their functions in the pancreatic β-cell.

Impact of Anti-inflammatory Cytokines on Islet Cell Viability and Function

As outlined above, exposure of cells to anti-inflammatory cytokines can elevate the expression of anti-apoptotic genes, and this response might contribute to cytoprotection. In this context, several studies have revealed that human islets and rodent clonal β-cells are less vulnerable to a range of cytotoxic stimuli following exposure to IL-13, IL-4 and IL-10 either alone or in combination.9,32-35 The data confirm that the protective response is dose-dependent32,33 and often, but not always, a cumulative effect is observed when more than a single cytokine is administered.35 Mechanistically, studies from our laboratory have indicated that the Jak/STAT6 pathway may be an important mediator of the cytoprotective response since pharmacological inhibition of Jak2, Jak3 or all Jak family members, diminishes the protective effect of IL4 or IL-13.32,34 Additional evidence derives from studies with an INS-1E cell line conditionally expressing PTP-BL, a phosphatase which antagonises STAT6 phosphorylation.65 Overexpression of PTP-BL not only reduced pSTAT6 levels in cells exposed to IL-4, but it also attenuated the improvement in mitochondrial metabolism (as measured by MTS assay) associated with cytokine exposure.34 In addition, induction of PTP-BL antagonised the improved viability of serum starved cells caused by IL-13 (serum deprived cells: 37.1±1.1% cell death, IL-13 (20ng/ml): 27.2±0.5%, IL-13 + PTP-BL: 33.1±1.7%; p<0.01 (calculated by Student's t-test) vs IL-13 treatment alone n=5). These data are consistent with the involvement of STAT6 in mediating the responses to IL-4 and IL-13 although it should also be noted that other STAT isoforms are dephosphorylated by PTP-BL.65 This may be important since, for example, STAT3 also becomes phosphorylated in response to IL-13 in β-cells.32 However, we consider it unlikely that STAT3 contributes directly to the cytoprotective actions of IL-13 for 2 principal reasons. Firstly, both IL-13 and a different cytokine, IL-6, cause a similar transient elevation in pSTAT3 levels in β-cells, but they exert entirely opposite effects on cell viability. Thus while IL-13 is cytoprotective, IL-6 enhances toxicity. Furthermore, using a STAT3 specific reporter, it was shown that IL-13 fails to promote STAT3 mediated transcription in INS-1E cells whereas this was strongly induced by IL-6. Thus, it seems likely that cytokine-induced STAT6 activation is responsible for mediating cytoprotection in β-cells.

While, as has already been intimated, the gene targets of STAT6 remain unknown in the β-cell, various groups have independently verified that sIL-1Ra is regulated in a STAT6 dependent manner.71,74,75 sIL-1Ra, rather than inducing downstream signaling cascades, elicits its anti-inflammatory effects by interacting directly with the interleukin-1 receptor thereby blocking IL-1β binding. Considering the recent finding that sIL-1Ra can be released directly from islet cells,76 it is an intriguing possibility that STAT6 may regulate the secretion of sIL-1Ra from the islet which could contribute to the cytoprotection offered by IL-4 and IL-13 in the presence of IL-1β.

It was noted above that the PI-3K/Akt pathway is activated in response to IL-13 and IL-4 in islet cells and, intriguingly, inhibition of this pathway with wortmannin exerted a differential effect on the protection offered by IL-434 and IL-13.32 IL-4 induced responses were sensitive to wortmannin whereas those mediated by IL-13 were not. These results imply that there may be important differences in the signaling pathways induced by these cytokines. This could reflect the fact that, in the receptor complex, IL-4Rα can interact with either IL-13Rα or the common γ-chain, thereby leaving open the possibility that differential signaling might ensue when IL-4 or IL-13 is present. This differential effect of the 2 cytokines has also been described elsewhere, particularly in the context of asthma.77

One mechanism by which anti-inflammatory cytokines might offer cytoprotection to pancreatic β-cells is by reducing the level of oxidative and/or nitrosative stress. It is known that human islet cells are susceptible to oxidative stress and that, in particular, β-cells express many of the key anti-oxidant enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase and catalase) at only very low levels.78,79 This is significant because pro-inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β, promote the expression of iNOS and thereby increase the local production of nitric oxide (NO). Importantly, treatment of clonal β-cells with IL-13, IL-4 or IL-10 reduced nitrite accumulation (an index of NO production) during exposure to IL-1β.32 However, while this is suggestive of a possible mechanism of cytoprotection, examination of the wider literature yields a more equivocal picture. Hence, while one study reported that IL-4 inhibited IL-1β induced NO production in rat islets,80 this was not seen in separate work employing IL-10 despite the fact that IL-10 reduced basal NO accumulation. Importantly, all 3 anti-inflammatory cytokines reduced iNOS expression in RINm5F cells.35 By contrast, IL-10 or IL-4 treatment had no effect on the mRNA expression of iNOS or other antioxidant genes in a further report24 although, somewhat surprisingly, eNOS levels were enhanced by IL-10 treatment.24 Studies in other systems have shown that anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 or IL-10 can impede NFκB activation under certain circumstances, possibly through IκB stabilization81-83 and, if this happens in β-cells, then this might account for some of the responses observed. Finally, one recent study has revealed that pro-inflammatory cytokines reduced the expression of peroxiredoxin 6 in clonal β-cells, thereby rendering these cells more vulnerable to oxidative stress.84 IL-4 reversed this effect.

Taken together (and allowing for the fact that not all data are fully concordant) it can be argued that anti-inflammatory cytokines are likely to inhibit IL-1β induced NO production upstream of iNOS expression in β-cells; conceivably by modulation of NFκB activation. The resultant dampening of nitrosative (and possibly oxidative) stress is then beneficial. However, this mechanism is unlikely to explain completely the effects of anti-inflammatory cytokines because these molecules are protective against a range of cytotoxic insults (e.g. serum deprivation or palmitate treatment), not all of which are highly dependent on the generation of oxidative or nitrosative stress for their deleterious effects. Rather, we speculate that IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 may induce a more general ‘cytoprotective phenotype’ by influencing a distal step in the control of viability.

Effects of Anti-inflammatory Cytokines on Beta-cell Function

While it is well established that pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-1β, can inhibit glucose stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS), the impact of anti-inflammatory cytokines on β-cell function has received much less attention. Thus, there are few data addressing the direct impact of anti-inflammatory cytokines on GSIS, although a number of studies have revealed that these molecules reverse the inhibitory effects of pro-inflammatory factors on insulin secretion from clonal β-cell36 and human islets.9 Furthermore, one study which correlated β-cell function with the levels of cytokines released from isolated human PBMCs, found that IL-10, IL-13 and IL-4 were all positively correlated with glucagon-stimulated C-peptide levels, used as a proxy of β-cell function.85 The mechanism that underlies this effect has not been addressed, although it may reflect the modulation of IL-1β signaling as previously described in the context of NO generation. The effect of anti-inflammatory cytokines on the secretion of hormones from other endocrine islet cells has not been examined. However, it is worth highlighting that IL-6 enhances both insulin and glucagon secretion86,87 and that IL-6 can signal via STAT3. Conceivably, therefore, other cytokines which promote STAT3 phosphorylation (such as IL-10) might also influence hormone secretion in similar ways.

Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Anti-inflammatory Cytokine Signaling Pathways in Type 1 Diabetes

Despite the evidence outlined in this review, the potential of anti-inflammatory cytokines and their signaling mechanisms as therapeutic targets in type 1 diabetes has received surprisingly little attention. This may be because the most strenuous efforts are being invested to understand the role played by pro-inflammatory mediators. Nevertheless, data from the NOD mouse have shown that the adoptive transfer of immunomodulatory cells preferentially secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., M2 macrophages, regulatory T-cells), leads to a reduction in diabetes incidence.88,89 In addition, there are also data which imply that manipulation of anti-inflammatory cytokine signaling could be therapeutically effective. Among these are results revealing that helminth infections dramatically attenuate the progression of type 1 diabetes (at least in NOD mice).90,91 Superficially, this seems an idiosyncratic observation but the importance may lie in the fact that such infections cause fundamental changes in the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines from circulating immune cells which may then impact on disease progression at the islet level. Thus, by study of such phenomena it might be possible to develop still more targeted approaches in which the actions of anti-inflammatory cytokines could be harnessed to combat the progression of disease.

Funding

Work in the authors’ laboratory is funded by Diabetes UK (12/0004505), the European Union's Seventh Framework Program PEVNET (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement number 261441 and with the support of the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes (nPOD), a collaborative type 1 diabetes research project sponsored by the JDRF, and with a JDRF research grant awarded to the nPOD-V Consortium. Organ procurement organisations partnering with nPOD to provide research resources are listed at www.jdrfnpod.org/our-partners.php.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1. Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1143-51; PMID:19266182; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1276-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AG, Marselli L, Masini M, Dionisi S, Mosca F, Boggi U, Muda AO, Del Prato S, et al. . Coxsackie B4 virus infection of beta cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:5115-20; PMID:17360338; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0700442104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tauriainen S, Oikarinen S, Oikarinen M, Hyoty H. Enteroviruses in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Semin Immunopathol 2011; 33:45-55; PMID:20424841; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00281-010-0207-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coppieters KT, Boettler T, von Herrath M. Virus infections in type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2:a007682; PMID:22315719; http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a007682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richardson SJ, Morgan NG, Foulis AK. Pancreatic pathology in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pathol 2014; 25(1):80-92; PMID:24522639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campbell-Thompson ML, Atkinson MA, Butler AE, Chapman NM, Frisk G, Gianani R, Giepmans BN, von Herrath MG, Hyöty H, Kay TW, et al. . The diagnosis of insulitis in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2013; 56:2541-3; PMID:24006089; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-3043-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. In't Veld P. Insulitis in human type 1 diabetes: The quest for an elusive lesion. Islets 2011; 3:131-8; PMID:21606672; http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/isl.3.4.15728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willcox A, Richardson SJ, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. Analysis of islet inflammation in human type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol 2009; 155:173-81; PMID:19128359; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03860.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marselli L, Dotta F, Piro S, Santangelo C, Masini M, Lupi R, Realacci M, del Guerra S, Mosca F, Boggi U, et al. . Th2 cytokines have a partial, direct protective effect on the function and survival of isolated human islets exposed to combined proinflammatory and Th1 cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86:4974-8; PMID:11600573; http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jcem.86.10.7938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eizirik DL, Mandrup-Poulsen T. A choice of death–the signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia 2001; 44:2115-33; PMID:11793013; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001250100021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eizirik DL, Miani M, Cardozo AK. Signalling danger: endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in pancreatic islet inflammation. Diabetologia 2013; 56:234-41; PMID:23132339; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2762-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berman MA, Sandborg CI, Wang Z, Imfeld KL, Zaldivar F Jr., Dadufalza V, Buckingham BA. Decreased IL-4 production in new onset type I insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Immunol 1996; 157:4690-6; PMID:8906850 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rapoport MJ, Mor A, Vardi P, Ramot Y, Winker R, Hindi A, Bistritzer T. Decreased secretion of Th2 cytokines precedes Up-regulated and delayed secretion of Th1 cytokines in activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Autoimmun 1998; 11:635-42; PMID:9878085; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jaut.1998.0240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szelachowska M, Kretowski A, Kinalska I. Decreased in vitro IL-4 corrected. and IL-10 production by peripheral blood in first degree relatives at high risk of diabetes type-I. Horm Met Res = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme 1998; 30:526-30; PMID:9761385; http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-978926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kretowski A, Mysliwiec J, Kinalska I. In vitro interleukin-13 production by peripheral blood in patients with newly diagnosed insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and their first degree relatives. Scand J Immunol 2000; 51:321-5; PMID:10736103; http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00693.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandrup-Poulsen T, Pickersgill L, Donath MY. Blockade of interleukin 1 in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010; 6:158-66; PMID:20173777; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2009.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rane SG, Lee JH, Lin HM. Transforming growth factor-beta pathway: role in pancreas development and pancreatic disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2006; 17:107-19; PMID:16257256; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL. Roles of cytokines in the pathogenesis and therapy of type 1 diabetes. Cell Biochem Biophys 2007; 48:159-63; PMID:17709885; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12013-007-0029-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Christen U, von Herrath MG. Manipulating the type 1 vs type 2 balance in type 1 diabetes. Immunol Res 2004; 30:309-25; PMID:15531772; http://dx.doi.org/10.1385/IR:30:3:309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rapoport MJ, Jaramillo A, Zipris D, Lazarus AH, Serreze DV, Leiter EH, Cyopick P, Danska JS, Delovitch TL. Interleukin 4 reverses T cell proliferative unresponsiveness and prevents the onset of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Exp Med 1993; 178:87-99; PMID:8315397; http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.178.1.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pennline KJ, Roque-Gaffney E, Monahan M. Recombinant human IL-10 prevents the onset of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1994; 71:169-75; PMID:8181185; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/clin.1994.1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cameron MJ, Arreaza GA, Zucker P, Chensue SW, Strieter RM, Chakrabarti S, Delovitch TL. IL-4 prevents insulitis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in nonobese diabetic mice by potentiation of regulatory T helper-2 cell function. J Immunol 1997; 159:4686-92; PMID:9366391 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaccone P, Phillips J, Conget I, Gomis R, Haskins K, Minty A, Bendtzen K, Cooke A, Nicoletti F. Interleukin-13 prevents autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 1999; 48:1522-8; PMID:10426368; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.48.8.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papaccio G, Pisanti FA, Montefiano RD, Graziano A, Latronico MV. Th1 and Th2 cytokines exert regulatory effects upon islet microvascular areas in the NOD mouse. J Cell Biochem 2002; 86:651-64; PMID:12210732; http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcb.10250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tominaga Y, Nagata M, Yasuda H, Okamoto N, Arisawa K, Moriyama H, Miki M, Yokono K, Kasuga M. Administration of IL-4 prevents autoimmune diabetes but enhances pancreatic insulitis in NOD mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1998; 86:209-18; PMID:9473384; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/clin.1997.4471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rehman KK, Trucco M, Wang Z, Xiao X, Robbins PD. AAV8-mediated gene transfer of interleukin-4 to endogenous beta-cells prevents the onset of diabetes in NOD mice. Mol Ther: J Am Soc Gene Ther 2008; 16:1409-16; PMID:18560422; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mt.2008.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruffner MA, Robbins PD. Dendritic cells transduced to express interleukin 4 reduce diabetes onset in both normoglycemic and prediabetic nonobese diabetic mice. PloS one 2010; 5:e11848; PMID:20686610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith DK, Korbutt GS, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Kao D, Rajotte RV, Elliott JF. Interleukin-4 or interleukin-10 expressed from adenovirus-transduced syngeneic islet grafts fails to prevent beta cell destruction in diabetic NOD mice. Transplantation 1997; 64:1040-9; PMID:9381527; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199710150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moritani M, Yoshimoto K, Tashiro F, Hashimoto C, Miyazaki J, Ii S, Kudo E, Iwahana H, Hayashi Y, Sano T, et al. . Transgenic expression of IL-10 in pancreatic islet A cells accelerates autoimmune insulitis and diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice. Int Immunol 1994; 6:1927-36; PMID:7696210; http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intimm/6.12.1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pauza ME, Neal H, Hagenbaugh A, Cheroutre H, Lo D. T-cell production of an inducible interleukin-10 transgene provides limited protection from autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes 1999; 48:1948-53; PMID:10512358; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.48.10.1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jorns A, Arndt T, Zu Vilsendorf AM, Klempnauer J, Wedekind D, Hedrich HJ, Marselli L, Marchetti P, Harada N, Nakaya Y, et al. . Islet infiltration, cytokine expression and beta cell death in the NOD mouse, BB rat, komeda rat, LEW.1AR1-iddm rat and humans with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014; 57:512-21; PMID:24310561; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-3125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Russell MA, Cooper AC, Dhayal S, Morgan NG. Differential effects of interleukin-13 and interleukin-6 on Jak/STAT signaling and cell viability in pancreatic beta-cells. Islets 2013; 5; PMID:23510983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaminski A, Kaminski ER, Morgan NG. Pre-incubation with interleukin-4 mediates a direct protective effect against the loss of pancreatic beta-cell viability induced by proinflammatory cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol 2007; 148:583-8; PMID:17403060; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03375.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaminski A, Welters HJ, Kaminski ER, Morgan NG. Human and rodent pancreatic beta-cells express IL-4 receptors and IL-4 protects against beta-cell apoptosis by activation of the PI3K and JAK/STAT pathways. Biosci Rep 2010; 30:169-75; PMID:19531027; http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BSR20090021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Souza KL, Gurgul-Convey E, Elsner M, Lenzen S. Interaction between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in insulin-producing cells. J Endocrinol 2008; 197:139-50; PMID:18372240; http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-07-0638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xu AJ, Zhu W, Tian F, Yan LH, Li T. Recombinant adenoviral expression of IL-10 protects beta cell from impairment induced by pro-inflammatory cytokine. Mol Cell Biochem 2010; 344:163-71; PMID:20658311; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11010-010-0539-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dirice E, Kahraman S, Jiang W, El Ouaamari A, De Jesus DF, Teo AK, Hu J, Kawamori D, Gaglia JL, Mathis D, et al. . Soluble factors secreted by T cells promote beta-cell proliferation. Diabetes 2014; 63:188-202; PMID:24089508; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db13-0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rael EL, Lockey RF. Interleukin-13 signaling and its role in asthma. World Allergy Organ J 2011; 4:54-64; PMID:23283176; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/WOX.0b013e31821188e0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Donath MY, Boni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Halban PA, Ehses JA. Cytokine production by islets in health and diabetes: cellular origin, regulation and function. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2010; 21:261-7; PMID:20096598; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2009.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Campbell IL, Cutri A, Wilson A, Harrison LC. Evidence for IL-6 production by and effects on the pancreatic beta-cell. J Immunol 1989; 143:1188-91; PMID:2501390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Taylor-Fishwick DA, Weaver JR, Grzesik W, Chakrabarti S, Green-Mitchell S, Imai Y, Kuhn N, Nadler JL. Production and function of IL-12 in islets and beta cells. Diabetologia 2013; 56:126-35; PMID:23052055; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2732-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olsson A, Johansson U, Korsgren O, Frisk G. Inflammatory gene expression in coxsackievirus B-4-infected human islets of langerhans. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 330:571-6; PMID:15796921; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schulte BM, Lanke KH, Piganelli JD, Kers-Rebel ED, Bottino R, Trucco M, Huijbens RJ, Radstake TR, Engelse MA, de Koning EJ, et al. . Cytokine and chemokine production by human pancreatic islets upon enterovirus infection. Diabetes 2012; 61:2030-6; PMID:22596052; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db11-1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jiang H, Harris MB, Rothman P. IL-4/IL-13 signaling beyond JAK/STAT. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 105:1063-70; PMID:10856136; http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2000.107604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kelly-Welch AE, Hanson EM, Boothby MR, Keegan AD. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science 2003; 300:1527-8; PMID:12791978; http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1085458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fichtner-Feigl S, Strober W, Kawakami K, Puri RK, Kitani A. IL-13 signaling through the IL-13alpha2 receptor is involved in induction of TGF-beta1 production and fibrosis. Nat Med 2006; 12:99-106; PMID:16327802; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nm1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Donnelly RP, Dickensheets H, Finbloom DS. The interleukin-10 signal transduction pathway and regulation of gene expression in mononuclear phagocytes. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1999; 19:563-73; PMID:10433356; http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/107999099313695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sheppard P, Kindsvogel W, Xu W, Henderson K, Schlutsmeyer S, Whitmore TE, Kuestner R, Garrigues U, Birks C, Roraback J, et al. . IL-28, IL-29 and their class II cytokine receptor IL-28R. Nat Immunol 2003; 4:63-8; PMID:12469119; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ni873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ng SF, Lin RC, Laybutt DR, Barres R, Owens JA, Morris MJ. Chronic high-fat diet in fathers programs beta-cell dysfunction in female rat offspring. Nature 2010; 467:963-6; PMID:20962845; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature09491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. David M, Bertoglio J, Pierre J. TNF-alpha potentiates IL-4/IL-13-induced IL-13Ralpha2 expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002; 973:207-9; PMID:12485861; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04633.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Caput D, Laurent P, Kaghad M, Lelias JM, Lefort S, Vita N, Ferrara P. Cloning and characterization of a specific interleukin (IL)-13 binding protein structurally related to the IL-5 receptor alpha chain. J Biol Chem 1996; 271:16921-6; PMID:8663118; http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.271.28.16921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lind K, Richardson SJ, Leete P, Morgan NG, Korsgren O, Flodstrum-Tullberg M. Induction of an antiviral state and attenuated coxsackievirus replication in type III interferon treated primary human pancreatic islets. J Virology 2013; 87(13):7646-54; PMID:23637411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Klein C, Shah N, Grimbacher B. IL-10 and IL-10 receptor defects in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011; 1246:102-7; PMID:22236434; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bugawan TL, Mirel DB, Valdes AM, Panelo A, Pozzilli P, Erlich HA. Association and interaction of the IL4R, IL4, and IL13 loci with type 1 diabetes among Filipinos. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72:1505-14; PMID:12748907; http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/375655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mirel DB, Valdes AM, Lazzeroni LC, Reynolds RL, Erlich HA, Noble JA. Association of IL4R haplotypes with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2002; 51:3336-41; PMID:12401728; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.51.11.3336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Risma KA, Wang N, Andrews RP, Cunningham CM, Ericksen MB, Bernstein JA, Chakraborty R, Hershey GK. V75R576 IL-4 receptor alpha is associated with allergic asthma and enhanced IL-4 receptor function. J Immunol 2002; 169:1604-10; PMID:2133990; http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qu HQ, Tessier MC, Frechette R, Bacot F, Polychronakos C. Lack of association of type 1 diabetes with the IL4R gene. Diabetologia 2006; 49:958-61; PMID:16538488; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0199-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Erlich HA, Lohman K, Mack SJ, Valdes AM, Julier C, Mirel D, Noble JA, Morahan GE, Rich SS, Type I Diabetes Genetics Consortium . Association analysis of SNPs in the IL4R locus with type I diabetes. Genes Immun 2009; 10 Suppl 1:S33-41; PMID:19956098; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/gene.2009.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saxena M, Agrawal CC, Bid HK, Banerjee M. An interleukin-10 gene promoter polymorphism (−592A/C) associated with type 2 diabetes: a North Indian study. Biochem Genet 2012; 50:549-59; PMID:22298356; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10528-012-9499-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hershey GK. IL-13 receptors and signaling pathways: an evolving web. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111:677-90; quiz 91; PMID:12704343; http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2003.1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hirsch E, Costa C, Ciraolo E. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases as a common platform for multi-hormone signaling. J Endocrinol 2007; 194:243-56; PMID:17641274; http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-07-0097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hebenstreit D, Wirnsberger G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A. Signaling mechanisms, interaction partners, and target genes of STAT6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2006; 17:173-88; PMID:16540365; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Welters HJ, Oknianska A, Erdmann KS, Ryffel GU, Morgan NG. The protein tyrosine phosphatase-BL, modulates pancreatic beta-cell proliferation by interaction with the Wnt signalling pathway. J Endocrinol 2008; 197:543-52; PMID:18413347; http://dx.doi.org/10.1677/JOE-07-0262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Moore F, Colli ML, Cnop M, Esteve MI, Cardozo AK, Cunha DA, Bugliani M, Marchetti P, Eizirik DL. PTPN2, a candidate gene for type 1 diabetes, modulates interferon-gamma-induced pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 2009; 58:1283-91; PMID:19336676; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db08-1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nakahira M, Tanaka T, Robson BE, Mizgerd JP, Grusby MJ. Regulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling by the tyrosine phosphatase PTP-BL. Immunity 2007; 26:163-76; PMID:17306571; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lu X, Chen J, Sasmono RT, Hsi ED, Sarosiek KA, Tiganis T, Lossos IS. T-cell protein tyrosine phosphatase, distinctively expressed in activated-B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, is the nuclear phosphatase of STAT6. Mol Cell Biol 2007; 27:2166-79; PMID:17210636; http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.01234-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Downes K, Plagnol V, Bailey R, Nejentsev S, Field SF, Payne F. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet 2007; 39:857-64; PMID:17554260; http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Santin I, Moore F, Colli ML, Gurzov EN, Marselli L, Marchetti P, Eizirik DL. PTPN2, a candidate gene for type 1 diabetes, modulates pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis via regulation of the BH3-only protein Bim. Diabetes 2011; 60:3279-88; PMID:21984578; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db11-0758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen Z, Lund R, Aittokallio T, Kosonen M, Nevalainen O, Lahesmaa R. Identification of novel IL-4/Stat6-regulated genes in T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2003; 171:3627-35; PMID:14500660; http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wurster AL, Rodgers VL, White MF, Rothstein TL, Grusby MJ. Interleukin-4-mediated protection of primary B cells from apoptosis through Stat6-dependent up-regulation of Bcl-xL. J Biol Chem 2002; 277:27169-75; PMID:12023955; http://dx.doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M201207200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ohmori Y, Smith MF Jr., Hamilton TA. IL-4-induced expression of the IL-1 receptor antagonist gene is mediated by STAT6. J Immunol 1996; 157:2058-65; PMID:8757327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kiuchi N, Nakajima K, Ichiba M, Fukada T, Narimatsu M, Mizuno K, Hibi M, Hirano T. STAT3 is required for the gp130-mediated full activation of the c-myc gene. J Exp Med 1999; 189:63-73; PMID:9874564; http://dx.doi.org/10.1084/jem.189.1.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vallania F, Schiavone D, Dewilde S, Pupo E, Garbay S, Calogero R, Pontoglio M, Provero P, Poli V. Genome-wide discovery of functional transcription factor binding sites by comparative genomics: the case of Stat3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106:5117-22; PMID:19282476; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0900473106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wan L, Lin CW, Lin YJ, Sheu JJ, Chen BH, Liao CC, Tsai Y, Lin WY, Lai CH, Tsai FJ. Type I IFN induced IL1-Ra expression in hepatocytes is mediated by activating STAT6 through the formation of STAT2: STAT6 heterodimer. J Cell Mol Med 2008; 12:876-88; PMID:18494930; http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00143.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gabay C, Porter B, Guenette D, Billir B, Arend WP. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 enhance the effect of IL-1beta on production of IL-1 receptor antagonist by human primary hepatocytes and hepatoma HepG2 cells: differential effect on C-reactive protein production. Blood 1999; 93:1299-307; PMID:9949173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Glas R, Sauter NS, Schulthess FT, Shu L, Oberholzer J, Maedler K. Purinergic P2´7 receptors regulate secretion of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and beta cell function and survival. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1579-88; PMID:19396427; http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Munitz A, Brandt EB, Mingler M, Finkelman FD, Rothenberg ME. Distinct roles for IL-13 and IL-4 via IL-13 receptor alpha1 and the type II IL-4 receptor in asthma pathogenesis. Proc Natl AcadSciU S A 2008; 105:7240-5; PMID:18480254; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0802465105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lenzen S. Oxidative stress: the vulnerable beta-cell. Biochem Soc Trans 2008; 36:343-7; PMID:18481954; http://dx.doi.org/10.1042/BST0360343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lenzen S, Drinkgern J, Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med 1996; 20:463-6; PMID:8720919; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Sandler S, Sternesjo J. Interleukin 4 impairs rat pancreatic islet function in vitro by an action different to that of interleukin 1. Cytokine 1995; 7:296-300; PMID:7640349; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/cyto.1995.0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Raychaudhuri B, Fisher CJ, Farver CF, Malur A, Drazba J, Kavuru MS, Thomassen MJ. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production by human alveolar macrophages. Cytokine 2000; 12:1348-55; PMID:10975994; http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/cyto.2000.0721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yu M, Qi X, Moreno JL, Farber DL, Keegan AD. NF-kappaB signaling participates in both RANKL- and IL-4-induced macrophage fusion: receptor cross-talk leads to alterations in NF-kappaB pathways. J Immunol 2011; 187:1797-806; PMID:21734075; http://dx.doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1002628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shames BD, Selzman CH, Meldrum DR, Pulido EJ, Barton HA, Meng X, Harken AH, McIntyre RC Jr. Interleukin-10 stabilizes inhibitory kappaB-alpha in human monocytes. Shock 1998; 10:389-94; PMID:9872676; http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00024382-199812000-00002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Paula FM, Ferreira SM, Boschero AC, Souza KL. Modulation of the peroxiredoxin system by cytokines in insulin-producing RINm5F cells: down-regulation of PRDX6 increases susceptibility of beta cells to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013; 374:56-64; PMID:23623867; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pfleger C, Meierhoff G, Kolb H, Schloot NC, p520/521 Study G. Association of T-cell reactivity with beta-cell function in recent onset type 1 diabetes patients. Jautoimmun 2010; 34:127-35; PMID:19744828; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA, Hammar EB, Van Lommel L, Quintens R, Martens G, Kerr-Conte J, Pattou F, Berney T, Pipeleers D, et al. . Interleukin-6 regulates pancreatic alpha-cell mass expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:13163-8; PMID:18719127; http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801059105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Suzuki T, Imai J, Yamada T, Ishigaki Y, Kaneko K, Uno K, Hasegawa Y, Ishihara H, Oka Y, Katagiri H. Interleukin-6 enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells: potential involvement of the PLC-IP3-dependent pathway. Diabetes 2011; 60:537-47; PMID:21270264; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db10-0796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Parsa R, Andresen P, Gillett A, Mia S, Zhang XM, Mayans S, Holmberg D, Harris RA. Adoptive transfer of immunomodulatory M2 macrophages prevents type 1 diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes 2012; 61:2881-92; PMID:22745325; http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/db11-1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mukherjee R, Chaturvedi P, Qin HY, Singh B. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells generated in response to insulin B:9-23 peptide prevent adoptive transfer of diabetes by diabetogenic T cells. J Autoimmu 2003; 21:221-37; PMID:14599847; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0896-8411(03)00114-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zaccone P, Cooke A. Helminth mediated modulation of type 1 diabetes (T1D). Int J Parasitol 2013; 43:311-8; PMID:23291464; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zaccone P, Cooke A. Vaccine against autoimmune disease: can helminths or their products provide a therapy? Curr Opin Immunol 2013; 25:418-23; PMID:23465465; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]