Abstract

Immunosuppressive pathways active within the tumor microenvironment must be targeted in combination to sufficiently bolster antitumor immune defenses. Inhibition of A2A adenosine receptor signaling in combination with immune checkpoint blockade enhances CD8+ T and NK cell anti-metastatic activity. This results in reduced metastatic burden and improved survival in pre-clinical models.

Keywords: adenosine, combination therapy, immune checkpoint, metastasis, PD-1, tumor-mediated immunosuppression

Antibody-directed blockade of immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4, is now established as a significant therapeutic modality for the treatment of cancer.1,2 Yet for some patients where an immune reaction exists, single immune checkpoint blockade may fail due to the multiple non-redundant immunosuppressive mechanisms that exist to facilitate tumor growth. Targeting multiple immune checkpoint molecules in tandem heightens objective response rates, however, the occurrence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) is also increased.3 It is therefore imperative to identify alternate immunosuppressive pathways active within the tumor that may be targeted in combination to strengthen antitumor immune defenses with minimal associated irAEs.

The immunosuppressive adenosinergic pathway has risen to prominence as an anticancer target due to its association to hypoxic conditions often evident within the tumor microenvironment. Generation of adenosine is mediated by the ectoenzyme CD73, expressed on both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cell types. In addition, tumor-derived CD73 is associated with increased migratory and invasive capacity and holds potential as a tumor biomarker for poor prognosis and metastatic progression.4,5 Adenosine acts through four adenosine receptors, in particular signaling via the A2A and A2B adenosine receptors both dampens immune effector functions and increases the prevalence and activity of immunosuppressive cell subsets.6,7 Previous pre-clinical investigations identified A2A and A2B adenosine receptor antagonism by small molecular inhibitors to be protective against metastatic progression of CD73+ tumors.7 Monotherapeutic activity of A2A, but not A2B, adenosine receptor inhibitors appeared mediated by lymphocytic populations as Rag−/−cγ−/− mice, lacking natural killer (NK), T, and B lymphocytes, rendered this therapy inactive.7 Due to this dependence on effector immune cell populations, particularly NK cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes, we hypothesized that targeting multiple immunosuppressive mechanisms in combination may increase anti-metastatic activity. In our recent study, we investigated whether immune checkpoint blockade in combination with targeted inhibition of A2A adenosine receptor signaling could further increase immune effector functions to reduce metastatic progression.8

We assessed the validity of this therapeutic combination in both an experimental lung and spontaneous metastasis mouse model, using B16F10-CD73hi melanoma and 4T1.2 mammary carcinoma, respectively. In both models, combining A2A adenosine receptor inhibition with mAbs targeting immune checkpoint molecules, in particular anti-PD-1, significantly improved the antitumor immune response comparative to single agent activity alone.8 This was observed as significantly prolonged survival in the spontaneously metastasizing 4T1.2 model. Similarly, pulmonary metastatic burden of B16F10-CD73hi was significantly reduced in an apparent synergistic manner by this therapeutic combination.

Therapeutic efficacy for this combinatorial approach, targeting A2A adenosine receptor inhibition alongside anti-PD-1, was mediated by both CD8+ T and NK cells. In addition, a critical dependency on IFNγ and to a lesser extent perforin was also established. These molecules modulate the effector functions and cytotoxic capabilities of both CD8+ T and NK cells, essential for tumor clearance. Recently, a similar study examined the modulation of subcutaneous tumor growth and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in response to A2A adenosine receptor antagonism and anti-CTLA-4 blockade.9 Supporting our findings, they identified an enhanced antitumor response causing reduction in tumor growth, alongside increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells heightening the T effector: T regulatory ratio.9

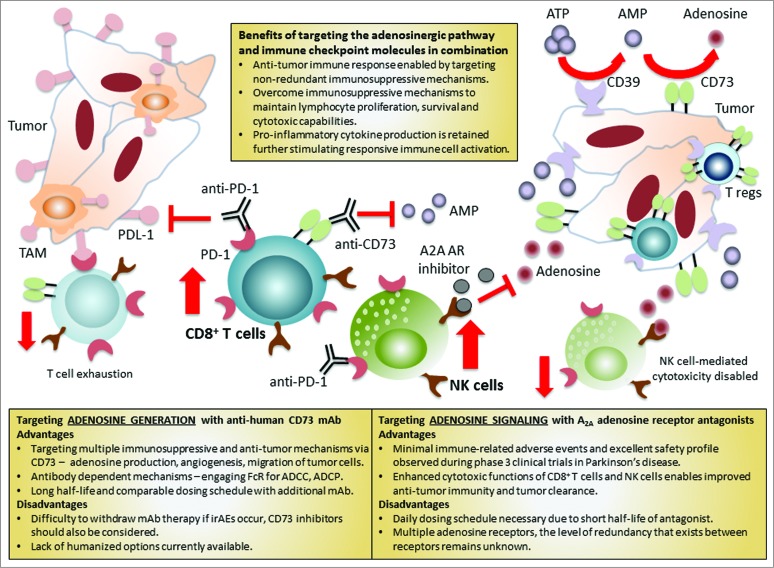

When targeting immunosuppressive adenosine, two main strategies have been employed with success in pre-clinical models. These approaches can be separated into those targeting generation of adenosine vs. adenosine signaling.4,7 While adenosine signaling has been solely targeted by small molecular inhibitors, both antibody blockade and pharmacological intervention have proven efficacy in preventing adenosine generation. The anticipated benefits and concerns surrounding these therapeutic approaches have been summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Targeting adenosine generation and signaling in combination with immune checkpoint blockade enhances antitumor response. Adenosine receptor signaling and interaction of the immune checkpoint receptor, PD-1, with its ligand, PDL-1, can decrease immune effector functions leading to tumor progression. Combinatorial approaches, which inhibit multiple immunosuppressive pathways in tandem, can improve antitumor immunity. Therapies directed toward both adenosine signaling and generation may be able to overcome adenosine-generated immunosuppression.

Diversity in function of CD73 (producing immunosuppressive adenosine, enhancing angiogenesis and mediating tumor and immune cell migration) suggests that this molecule may prove to be an excellent target for enhancing antitumor immunity. Antibody-blockade of CD73 may also enable additional immune-dependent benefits through Fc receptor-mediated responses. However, lack of humanized CD73 therapies provides an obstacle in proceeding to the clinic (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, pre-clinical studies have supported the combinatorial administration of anti-CD73 or targeted inhibition, by APCP, in tandem with immune checkpoint blockade.9,10 Tumor regression and in some cases complete rejection was observed via IFNγ-dependent expansion of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells.10 This further emphasizes the importance and possible cohesive nature of targeting immunosuppressive adenosine in combination with immune checkpoint blockade.

Understanding the tumor microenvironment most likely to benefit from adenosine-related therapies remains an important consideration for its clinical success. Presence of CD73 on the tumor may provide a biomarker to stratify patients for which these therapeutic options are likely to elicit an optimal antitumor immune response.7,8 While early, concurrent treatment appears most effective in mouse models, this dosing schedule may require optimization moving forward to clinical utility. Importantly, the presence of adenosine, or adenosine analog NECA, was shown to enhance PD-1, but not CTLA-4, expression on infiltrating T regs and tumor-specific CD8+ T cells.10 Antagonism of A2A adenosine receptor signaling, as well as CD73-deficiency, was able to reduce PD-1 expression. This apparent association suggests that targeting immunosuppressive adenosine preceding anti-PD-1 may potentiate therapeutic efficacy by increasing the ratio of antibody to target.

Advantageously, A2A adenosine receptor antagonists are currently undergoing clinical testing for Parkinson's disease and display excellent safety profiles, indicating a possible transition to clinical utility in an oncology setting. Targeting non-redundant immunosuppressive pathways in combination may improve overall response rates to cancer. Our study, with others, provides evidence for the clinical utility of targeting A2A adenosine receptor inhibition and immune checkpoint blockade to improve antitumor immunity.8-10

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs. Philip Darcy, Paul Beavis, and Sherene Loi for their collaboration and helpful discussions, Dr. Shin Foong Ngiow for his assistance with figures and Dr. Liam Town for his support of this work.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Professor Mark Smyth and Dr. John Stagg declare financial research support from Medimmune LLC.

Funding

The authors were supported by the Susan G. Komen For The Cure (JS and MJS), the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (MWLT, MJS), Cancer Council Queensland (AY), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (JS), and the 2013 Weekend to End Women's Cancers Grant (DM).

References

- 1.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, Gettinger SN, Smith DC, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Carvajal RD, Sosman JA, Atkins MB, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:2443-54; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:711-23; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:122-33; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stagg J, Divisekera U, McLaughlin N, Sharkey J, Pommey S, Denoyer D, Dwyer KM, Smyth MJ. Anti-CD73 antibody therapy inhibits breast tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2010; 107:1547-52; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0908801107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loi S, Pommey S, Haibe-Kains B, Beavis PA, Darcy PK, Smyth MJ, Stagg J. CD73 promotes anthracycline resistance and poor prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:11091-96; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1222251110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohta A, Gorelik E, Prasad SJ, Ronchese F, Lukashev D, Wong MK, Huang X, Caldwell S, Liu K, Smith P, et al. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2006; 103:13132-37; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0605251103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beavis PA, Divisekera U, Paget C, Chow MT, John LB, Devaud C, Dwyer K, Stagg J, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK. Blockade of A2A receptors potently suppresses the metastasis of CD73+ tumors. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2013; 110:14711-16; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1308209110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mittal D, Young A, Stannard K, Yong M, Teng MW, Allard B, Stagg J, Smyth MJ. Antimetastatic effects of blocking PD-1 and the adenosine A2A receptor. Cancer Res 2014; 74:3652-58; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iannone R, Miele L, Maiolino P, Pinto A, Morello S. Adenosine limits the therapeutic effectiveness of anti-CTLA4 mAb in a mouse melanoma model. Am J Cancer Res 2014; 4:172-81; PMID: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allard B, Pommey S, Smyth MJ, Stagg J. Targeting CD73 enhances the antitumor activity of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 mAbs. Clin Cancer Res 2013; 19:5626-35; PMID:; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]