Abstract

Many patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) do not receive allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) because they are unable to achieve a complete remission (CR) after reinduction chemotherapy. Starting in January 2003, we prospectively assigned patients with AML with high risk clinical features to pre-emptive alloHCT (p-alloHCT) as soon as possible after reinduction chemotherapy. High risk clinical features were associated with poor response to chemotherapy: 1) primary induction failure (PIF), 2) second or greater relapse, and 3) first complete remission interval <6 months. We hypothesized that any residual disease would be maximally reduced at the time of transplant resulting in the best milieu and most lead time for developing a graft versus leukemia effect resulting in improved long term overall survival without excess toxicity. This is an analysis of the effect of transplant timing on p-alloHCT in 30 patients with high risk clinical features out of 156 consecutive AML patients referred for alloHCT. We compared early p-alloHCT within 4 weeks of reinduction chemotherapy prior to count recovery with late p-alloHCT 4 weeks after reinduction chemotherapy with count recovery. Overall and progression free survival (OS, PFS) at 2 years were not significantly different for early versus late palloHCT (OS 23% versus 33%, p>0.1; PFS 18% versus 22%, p>0.1). Day 100 and one year transplant related mortality were similar (33.3% versus 22.2%, p>0.1 and 44.4% versus 42.9%, p>0.1, respectively). Pre-emptive alloHCT allowed 30 patients to be transplanted who would normally not receive alloHCT. Clinical outcomes for early p-alloHCT are similar to those for late p-alloHCT without excess toxicity. Early p-alloHCT is a feasible alternative to late p-alloHCT for maximizing therapy of AML that is poorly responsive to induction chemotherapy.

Keywords: relapsed or refractory AML, hypoplasia, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (alloHCT) for poor prognosis acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has been performed after achieving a complete remission (CR) in order to consolidate a patient's response to chemotherapy and prevent future relapse. Many patients, however, will not receive an alloHCT because they are unable to achieve a CR due to chemotherapy resistant or rapidly progressive disease. The overall clinical benefit of alloHCT in patients not in CR is uncertain because 1) any nascent graft versus leukemia (GVL) effects may be overtaken by expanding residual disease, and 2) gains from disease control may be outweighed by transplant related complications.

Residual leukemia is a contraindication to alloHCT in some transplant centers. An alternative approach is to perform alloHCT preemptively (p-alloHCT) after induction chemotherapy. In this setting, any residual disease has been maximally treated, allowing the donor graft the best chance to initiate a GVL effect and overcome the kinetics of disease progression. Because alloHCT requires advance planning, it is often not possible to make decisions about proceeding with p-alloHCT based upon a late restaging pre-transplant bone marrow biopsy. Therefore, starting in January 2003, the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) Blood and Marrow Transplant (BMT) and Leukemia services made a program-matic decision to prospectively treat all AML patients with high risk clinical features predictive of not achieving a CR with p-alloHCT. These high risk clinical features were defined as 1) primary induction failure (PIF), 2) second or greater relapse, and 3) first CR interval <6 months. Because alloHCT soon after induction chemotherapy may be associated with fatal toxicity, we analyzed the effect of p-alloHCT timing on safety, feasibility, and clinical effect of alloHCT in 30 AML patients with high risk clinical features.

PATIENTS, MATERIALS, AND METHODS

Disease, Response, and Treatment Group Definitions

AML was diagnosed according to the WHO and FAB classification schemes. [1-3] Cytogenetic risk was categorized according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology and Southwest Oncology Group (ECOG/SWOG) criteria: good risk (inv16, t[8;21], t[15;17]), poor risk (-5/del[5q], -7/del[7q], inv[3q], abn11q, 20q or 21q, del[9q], t[6;9], t[9;22], abn17p, and complex karyotype defined as three or more abnormalities), and intermediate (other and normal karyotypes). [4]

Early p-alloHCT was performed within 4 weeks of induction or reinduction chemotherapy prior to count recovery regardless of restaging bone marrow histo-pathology. Late p-alloHCT was performed after count recovery and >4 weeks after prior chemotherapy. Count recovery was defined as an absolute neutrophil count > 1×109/L and a platelet count > 100×109/L.

Bone marrow biopsies were performed ≤ 2 weeks prior to graft infusion to assess disease status. CR was defined as a normocellular bone marrow containing <5% blasts with count recovery. A hypoplastic bone marrow was defined as <20% bone marrow cellularity with <5% blasts. A refractory bone marrow was defined as ≥5% blasts, regardless of cellularity.

Patient Population

From January 2003 to March 2008, 156 consecutive adult AML patients were referred to the RPCI BMT program for alloHCT evaluation. Eighty-four of 156 (54%) patients did not receive alloHCT for reasons presented in Table 1. Seventy-two of 156 (46%) patients received alloHCT; 30 of these 72 were at high risk for not achieving a CR after induction chemotherapy based upon the following risk factors: primary induction failure (PIF), beyond 1st relapse, or remission interval <6 months. In this report, these patients, who were at high risk for not achieving a CR after re-induction chemotherapy, are referred to as having high risk clinical features. This is in distinction to poor risk cytogenetic features such as those specified by ECOG/SWOG criteria. Primary induction failure was defined as being unable to achieve a CR after one cycle of induction chemotherapy. Duval score for refractory AML was calculated as previously described. [5]

Table 1.

Reasons patients did not receive alloHCT

| Reason | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Rapid disease progression | 19 (23) |

| Patient refusal | 15 (18) |

| Reinduction chemotherapy related toxicity | 14 (17) |

| Received an autologous BMT | 11 (13) |

| Received transplant at another facility | 7 (8) |

| Co-morbidities | 4 (5) |

| Stable disease | 4 (5) |

| No donor | 3 (4) |

| Financial issues | 4 (5) |

| Psychosocial issues | 2 (2) |

| Age | 1 (1) |

Treatment

AML induction, consolidation, and reinduction chemotherapy were performed according to available clinical trials or institutional standards. Pre-emptive alloHCT was defined as alloHCT performed as soon as possible after reinduction chemo-therapy when AML was in a maximally reduced state. Pre-emptive alloHCT was prospectively planned for all patients with AML with high risk features as defined in Patient Population. Transplant conditioning regimens (myeloablative with busulfan / cyclophosphamide (CY) or etoposide / CY / total body irradiation (TBI) or reduced intensity with fludarabine (FLU)/ melphalan or FLU / CY) were assigned based upon baseline characteristics [age, Karnofsky performance status (KPS), co-morbidities, disease risk, and HLA matching]. Acute graft versus host disease (GvHD) prophylaxis was assigned as tacrolimus (TAC) only, TAC / mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), or a calcineurin inhibitor (TAC or cyclosporine) / methotrexate ± other (methylprednisolone of MMF). [6] TAC doses were adjusted to maintain blood levels of 5-10 ng/dl during the first 100 days then tapered off in the absence of GvHD by 6 months. MMF was discontinued at day +60 in the absence of GvHD.

Statistical Analysis

The RPCI Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective analysis. The null hypothesis for the study stated that early p-alloHCT was not associated with a decrease in overall survival (OS) or increase in transplant related mortality (TRM). The Pearson χ2 test or Fisher's exact text was used for univariate comparisons of categorical variables and the ANOVA F-test was used for comparisons of continuous variables. OS was defined as the time from the date of BMT (day 0) to the date of death due to any cause. Progression free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of BMT to first disease progression after BMT or death due to any cause. Patients who did not experience these events were censored at the time of last follow-up. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed and the difference was tested by the log-rank statistic. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 21 (IBM®, Armonk, NY) with two-sided type I error rate at 0.05.

RESULTS

Patient and Disease Characteristics

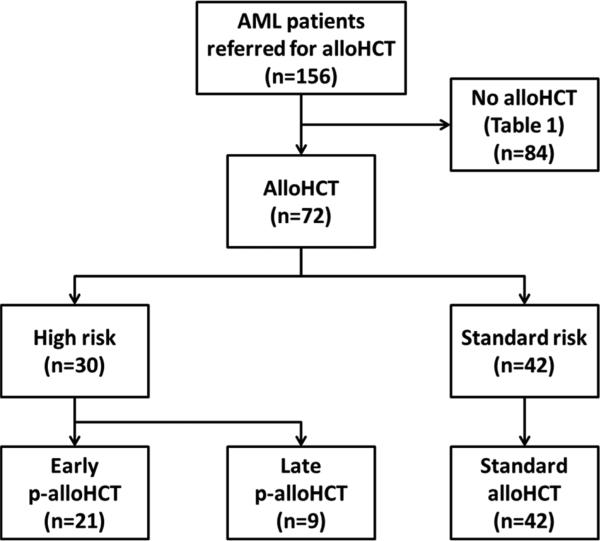

Characteristics for 72 patients receiving alloHCT are presented in Table 2. Thirty of these 72 (42%) patients were identified as having high risk clinical features predictive for not achieving CR after chemotherapy and prospectively assigned to p-alloHCT following reinduction chemotherapy. Twenty-one of these high risk clinical feature patients received early p-alloHCT. The other nine received late palloHCT due to delays in going to transplant for logistical reasons. Restaging bone marrow biopsies performed after reinduction and immediately prior to transplant demonstrated hypoplasia (n=11), refractory disease (n=9), and complete remission (n=1) in the 21 patients receiving early p-alloHCT. In the 9 patients receiving late p-alloHCT, restaging pre-transplant bone marrow biopsies demonstrated hypoplasia (n=2) and refractory disease (n=7). Forty-two of the 72 (58%) patients who did not have high risk clinical features achieved a complete remission with count recovery prior to alloHCT and received a standard alloHCT. Patient dispositions are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| Disease Risk | High | Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transplant type | Early p-alloHCT (n=21) | Late p-alloHCT (n=9) | Standard alloHCT (n=42) |

| Age | |||

| 18-40 | 4 (19) | 2 (22) | 14 (33) |

| 41-60 | 13 (62) | 6 (67) | 22 (52) |

| 61 + | 4 (19) | 1 (11) | 6 (14) |

| KPS | |||

| ≥90 | 1 (5) | 3 (33) | 20 (48) |

| ≤80 | 20 (95) | 6 (67) | 22 (52) |

| FAB Classification | |||

| M0 | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 6 (14) |

| M1 | 6 (29) | 2 (22) | 8 (19) |

| M2 | 9 (43) | 1 (11) | 13 (31) |

| M4 | 3 (14) | 2 (22) | 8 (19) |

| M5 | 2 (10) | 2 (22) | 6 (14) |

| M6 | 1 (5) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) |

| NOS | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| WBC at diagnosis | |||

| ≥30 × 109/L | 9 (43) | 2 (22) | 10 (24) |

| <30 × 109/L | 12 (57) | 7 (78) | 32 (76) |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Good | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Intermediate | 16 (76) | 6 (67) | 22 (52) |

| Poor | 3 (14) | 3 (33) | 20 (48) |

| De novo versus secondary AML | |||

| De novo | 17 (81) | 9 (100) | 30 (71) |

| secondary | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 12 (29) |

| Induction chemotherapy regimen | |||

| 7 + 3 + other | 9 (43) | 4 (44) | 25 (60) |

| ATO* + AraC + Ida [18] | 8 (38) | 5 (56) | 13 (31) |

| AraC + Ida | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 4 (10) |

| Other | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1st reinduction chemotherapy regimen | |||

| None | 1 (5) | 3 (33) | 32 (76) |

| AraC + gemtuzumab | 7 (33) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) |

| AraC + anthracycline ± VP16 | 8 (38) | 3 (33) | 2 (5) |

| AraC | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 5 (12) |

| Mito + VP16 | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| Other | 2 (10) | 2 (22) | 1 (2) |

| Number of reinduction chemotherapy regimens | |||

| 0 | 1 (5) | 3 (33) | 32 (76) |

| 1 | 12 (57) | 2 (22) | 9 (21) |

| 2-4 | 8 (38) | 4 (44) | 1 (2) |

| Pre alloHCT gemtuzumab | |||

| Yes | 12 (57) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) |

| No | 9 (43) | 7 (78) | 42 (100) |

| AlloHCT regimen | |||

| Myeloablative conditioning | 1 (5) | 2 (22) | 18 (43) |

| Reduced intensity conditioning | 20 (95) | 7 (78) | 24 (57) |

| Donor type | |||

| Related | 8 (38) | 4 (44) | 20 (48) |

| Unrelated | 13 (62) | 5 (56) | 22 (52) |

| Graft source | |||

| Bone marrow ± peripheral blood | 1 (5) | (11) | 9 (21) |

| Peripheral blood | 20 (95) | 8 (89) | 33 (79) |

| HLA match | |||

| 10/10 | 14 (67) | 9 (100) | 39 (93) |

| 9/10 | 7 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (7) |

| Sex match | |||

| Match | 13 (62) | 8 (89) | 22 (52) |

| Mismatch | 8 (38) | 1 (11) | 20 (48) |

| Prior autoHCT | |||

| Yes | 3 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 (5) |

| No | 18 (86) | 9 (100) | 40 (95) |

| Restaging bone marrow status prior to alloHCT | |||

| Hypoplastic** | 11 (52) | 5 (56) | 0 (0) |

| Refractory disease*** | 9 (43) | 4 (44) | 0 (0) |

| CR | 1 (5) | 0 (0) | 42 (100) |

| GVHD prophylaxis | |||

| TAC or CSA/MTX ± other | 11 (52) | 8 (9) | 29 (69) |

| TAC/MMF | 6 (29) | 1 (11) | 13 (31) |

| TAC/MTX | 5 (24) | 4 (44) | 18 (43) |

| FEV1 (%) | |||

| Median (range) | 91.9 (61.6-119.4) | 87 (61-130) | 99 (48-124) |

| DLCO corrected (%) | |||

| Median (range) | 79 (42.9-113) | 76 (56-106) | 80 (38-110) |

| Ejection Fraction (%) | |||

| Median (range) | 56 (50-75) | 60 (55-67) | 60 (44-75) |

| Duval score [5] | |||

| 0 | 2 (9.5) | 1 (11.1) | NA |

| 1 | 6 (26.8) | 3 (33.3) | NA |

| 2 | 8 (38.1) | 3 (33.3) | NA |

| ≥3 | 5 (23.8) | 2 (22.2) | NA |

Key. 7+3: cytarabine × 7 days and daunorubicin × 3 days; AlloHCT: allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; AraC: cytarabine; ATO: arsenic trioxide; AutoHCT: autologous hematopoietic cell transplant; BMT: blood and marrow transplantation; CR: complete remission; CSA: cyclosporine; FAB: French American British; HLA: human leukocyte antigen; Ida: idarubicin; KPS: Karnofsky performance score; Mito: mitoxantrone; MMF: mycophenolate mofetil; MTX: methotrexate (25 mg/m2 or 7.5 mg/m2 total); p-alloHCT: pre-emptive alloHCT; NA: not applicable; TAC: tacrolimus; VP16: etoposide; WBC: white blood cell

ATO was given as part of a phase 1 clinical trial [18]

hypoplastic was defined as <20% bone marrow cellularity with <5% blasts

refractory bone marrow was defined as ≥5% blasts, regardless of cellularity.

Figure 1. Patient dispositions and restaging bone marrow status prior to alloHCT.

The following analysis focuses on the 30 high risk AML patients who received either early (n=21) or late (n=9) p-alloHCT. A higher proportion of the early versus late p-alloHCT group received one or more reinduction regimens (95% versus 66%). Gemtuzumab ozogamicin use was more frequent in the early versus late p-alloHCT group (57% versus 22%, p = 0.09). A lower proportion of patients in the early versus late p-alloHCT group had leukemia with adverse cytogenetics. Both early and late p-alloHCT groups had similar distributions in Duval score, age, presenting WBC counts, FAB classification, history of prior transplant, and bone marrow status prior to alloHCT. Compared to late p-alloHCT, a greater proportion of patients receiving early p-alloHCT had a KPS ≤80 (95% versus 67%) at the time of transplant. A greater proportion of early versus late palloHCT patients received reduced intensity conditioning regimens prior to alloHCT (95% versus 78%). A higher proportion of patients in the early versus late p-alloHCT group received a graft from a <10/10 HLA matched unrelated donor (33% versus 0%). GVHD prophylaxis, graft source, and sex match were similar in both groups.

Clinical Outcomes

The median follow-up was 30 (range 13-70) months. Overall survival (23% versus 33%, p>0.1, Figure 2a) and PFS (18% versus 22%, p>0.1, Figure 2b) were not significantly different at 2 years between AML patients with high risk clinical features who received early versus late p-alloHCT. Three-year overall survival by low (0-1), intermediate (2), or high (>=3) Duval score was 46%, 9%, and 0%, respectively, for all 30 AML patients with high risk clinical features. As expected, OS and PFS at 2 years were better for patients receiving standard alloHCT (61% and 59%, respectively). Transplant related mortality was not significantly different between AML patients with high risk clinical features who received early versus late p-alloHCT at 100 days (33% versus 22%, p>0.1) and 1 year (44% versus 43%, p>0.1). Transplant related mortality for early p-alloHCT was associated with infectious causes in 3/7 patients who died before 100 days with no infectious deaths in an additional 2 TRM deaths between 100 days and 1 year post alloHCT. Transplant related mortality for late p-alloHCT was associated with infectious causes in 2/2 patients who died before 100 days with no infectious deaths in the 1 additional TRM death between 100 days and 1 year post alloHCT. All TRM due to infectious causes occurred within the first 100 days.

Figure 2a. Overall survival (OS) for patients receiving early or late preemptive alloHCT (p-alloHCT) stratified by pre-transplant bone marrow status.

There was no significant difference in OS for patients with high risk AML treated with early or late p-alloHCT (p>0.1). OS was better in patients with standard risk AML receiving standard alloHCT compared to those with high risk AML due to the majority of patients who achieved CR prior to transplant. Key. HE – High clinical risk AML early p-alloHCT, HL – High clinical risk AML late p-alloHCT, NS – not significant, SS – Standard risk AML standard alloHCT.

Figure 2b. Progression free survival (PFS) for patients receiving early or late preemptive alloHCT (p-alloHCT) stratified by pre-transplant bone marrow status.

There was no significant different in PFS for patients with high risk AML treated with early or late p-alloHCT (p>0.1). PFS was better in patients with standard risk AML receiving standard alloHCT compared to high risk AML due to the majority of patients who achieved CR prior to transplant. Key. HE – High clinical risk AML early alloHCT, HL – High clinical risk AML late p-alloHCT, NS – not significant, SS – Standard risk AML standard alloHCT.

Feasibility

A hypoplastic or refractory bone marrow would normally preclude alloHCT because of the uncertain prognosis. The 30 AML patients with high risk clinical features in this study therefore would normally not undergo alloHCT. At our institute, however, all AML patients at high risk for incomplete remissions over this time frame were prospectively planned for alloHCT regardless of bone marrow status. The median time between the end of the last reinduction therapy and infusion of the donor graft was significantly shorter in the early versus late palloHCT group (33 days versus 65 days, p<0.01).

DISCUSSION

AlloHCT after induction chemotherapy for patients with refractory AML is controversial because of the uncertain clinical benefit and potential excess toxicity. We demonstrate that early p-alloHCT prior to count recovery in AML patients with high risk clinical features associated with not achieving a CR after induction chemotherapy has acceptable mortality and results in clinical outcomes not significantly different from late p-alloHCT patients transplanted after count recovery. Large registry studies of alloHCT for residual AML have reported OS rates of 16-19% at 3 years and 10-27% at 5 years. [5, 7-9] These outcomes are comparable to our observed outcomes but should be interpreted cautiously due to differences in patient selection, conditioning regimens, and supportive care. The early and late p-alloHCT subgroups were significantly different in the timing of alloHCT. Certain disease related factors may have contributed to better disease control or response in the early p-alloHCT group such as a higher proportion of patients being treated with gemtuzumab ozogamicin and a lower proportion of patients with WBC < 30 × 109/L or adverse cytogenetics. [10-15] While these disease related factors predict the likelihood of achieving and maintaining a CR after chemotherapy, their importance may be outweighed by those predicting for higher transplant related mortality in the early p-alloHCT compared to the late p-alloHCT group. Duval, et al. (CIBMTR) and others have developed scoring systems to predict the survival of AML patients with active disease undergoing alloHCT. [5, 8, 16] The observed OS of p-alloHCT patients when analyzed by Duval score was comparable to reported values although the observed survival for patients with intermediate and high Duval scores was slightly below expected possibly due to the small number of observations. These findings suggest p-alloHCT may be an effective strategy in patients with lower Duval scores. For patients with intermediate and high Duval scores, the addition of novel agents to induction chemotherapy or conditioning to achieve better disease control prior to alloHCT may be beneficial.

The presence of a refractory or hypoplastic marrow immediately prior to alloHCT would normally preclude alloHCT because of the perceived excess toxicity and futility of alloHCT in the setting of uncontrolled disease. Indeed, in a large retrospective study of 67 patients younger than 40 years old with an HLA matched donor, only 30 received alloHCT with the most common reasons for not receiving transplant being primary refractory disease (n=15) and short duration of CR < 3 months (n=9). [17] Other reasons for not receiving transplant were the patient declined transplant (n=7), no documented reason (n=5), and the donor was not medically suitable (n=1). In our study, 30 out of 72 transplant eligible patients were predicted to have a low probability of achieving CR and only 1 out of 30 achieved a CR prior to transplant. These 30 patients are comparable to the 22 out of 67 (33%) refractory or short CR duration patients referenced above. In contrast, these patients were able to proceed to alloHCT with early p-alloHCT being feasible and comparable in safety and efficacy to late p-alloHCT.

Notably, many patients in our study did not receive alloHCT because of excess toxicity from reinduction chemotherapy, again suggesting that identification of less toxic and more effective salvage reinduction chemotherapy agents may further extend the availability of alloHCT.

In summary, our study suggests that pre-emptive early alloHCT prior to count recovery within four weeks of reinduction chemotherapy in high risk AML patients with hypoplastic or refractory bone marrows is feasible, has acceptable mortality, and results in clinical outcomes not significantly different from similar patients transplanted after count recovery. Early p-alloHCT may be preferable to late palloHCT as residual disease previously minimized with induction chemotherapy can rapidly progress in a short time interval. Although early p-alloHCT requires close coordination between leukemia and transplant programs and may be more difficult in the unrelated donor setting or in patients receiving leukemia therapy at a distance from the transplant center, these difficulties are offset by the ability to offer a potentially life-saving treatment to patients with few options.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the patients who participated in this study, the BMT clinical team for excellent patient care, and the BMT data managers. This work was supported by a generous grant from William Godin, RPCI and in part by NCI grant #P30-CA016056.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE

TH owns Novartis stock. All the other authors have no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposed revised criteria for the classification of acute myeloid leukemia. A report of the French-American-British Cooperative Group. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:620–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-4-620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. Proposal for the recognition of minimally differentiated acute myeloid leukaemia (AML-MO). Br J Haematol. 1991;78:325–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb04444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96:4075–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duval M, Klein JP, He W, Cahn JY, Cairo M, Camitta BM, et al. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute leukemia in relapse or primary induction failure. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3730–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen GL, Zhang Y, Hahn T, Abrams S, Ross M, Liu H, et al. Acute GVHD prophylaxis with standard-dose, micro-dose or no MTX after fludarabine/melphalan conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:248–53. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2013.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armistead PM, de Lima M, Pierce S, Qiao W, Wang X, Thall PF, et al. Quantifying the survival benefit for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsed acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:1431–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craddock C, Labopin M, Pillai S, Finke J, Bunjes D, Greinix H, et al. Factors predicting outcome after unrelated donor stem cell transplantation in primary refractory acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:808–13. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todisco E, Ciceri F, Oldani E, Boschini C, Mico C, Vanlint MT, et al. The CIBMTR score predicts survival of AML patients undergoing allogeneic transplantation with active disease after a myeloablative or reduced intensity conditioning: a retrospective analysis of the Gruppo Italiano Trapianto Di Midollo Osseo. Leukemia. 2013;27:2086–91. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rollig C, Thiede C, Gramatzki M, Aulitzky W, Bodenstein H, Bornhauser M, et al. A novel prognostic model in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of 909 patients entered into the prospective AML96 trial. Blood. 2010;116:971–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-267302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimwade D, Hills RK, Moorman AV, Walker H, Chatters S, Goldstone AH, et al. Refinement of cytogenetic classification in acute myeloid leukemia: determination of prognostic significance of rare recurring chromosomal abnormalities among 5876 younger adult patients treated in the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials. Blood. 2010;116:354–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnett AK, Hills RK, Hunter AE, Milligan D, Kell WJ, Wheatley K, et al. The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to low-dose Ara-C improves remission rate but does not significantly prolong survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: results from the LRF AML14 and NCRI AML16 pick-a-winner comparison. Leukemia. 2013;27:75–81. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hills RK, Kell J, Freeman S, Kjeldsen L, et al. Addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin to induction chemotherapy improves survival in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3924–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burnett AK, Hills RK, Milligan D, Kjeldsen L, Kell J, Russell NH, et al. Identification of patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia who benefit from the addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin: results of the MRC AML15 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:369–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang ES, Zeidan A, Tan W, Wilding GE, Ford LA, Wallace PK, et al. Cytoreduction with gemtuzumab ozogamicin and cytarabine prior to allogeneic stem cell transplant for relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:2085–8. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.603450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armand P, Kim HT, Cutler CS, Ho VT, Koreth J, Ritz J, et al. A prognostic score for patients with acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman E, Little C, Gee T, O'Reilly R, Clarkson B. Reasons that patients with acute myelogenous leukemia do not undergo allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:156–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201163260303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wetzler M, Andrews C, Ford LA, Tighe S, Barcos M, Sait SN, et al. Phase 1 study of arsenic trioxide, high-dose cytarabine, and idarubicin to down-regulate constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activity in patients aged <60 years with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:4861–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]