Abstract

Objective

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) significantly decreases HIV-associated morbidity, mortality, and HIV transmission through HIV viral load suppression. In high HIV prevalence settings, outreach strategies are needed to find asymptomatic HIV positive persons, link them to HIV care and ART, and achieve viral suppression.

Methods

We conducted a prospective intervention study in two rural communities in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and Mbabara district, Uganda. The intervention included home HIV testing and counseling (HTC), point-of-care CD4 count testing for HIV positive persons, referral to care, and one month then quarterly lay counselor follow-up visits. The outcomes at 12 months were linkage to care, and ART initiation and viral suppression among HIV positive persons eligible for ART (CD4≤350 cells/μL).

Findings

3,393 adults were tested for HIV (96% coverage), of whom 635 (19%) were HIV positive. At baseline, 36% of HIV positive persons were newly identified (64% were previously known to be HIV positive) and 40% were taking ART. By month 12, 619 (97%) of HIV positive persons visited an HIV clinic, and of 123 ART eligible participants, 94 (76%) initiated ART by 12 months. Of the 77 participants on ART by month 9, 59 (77%) achieved viral suppression by month 12. Among all HIV positive persons, the proportion with viral suppression (<1,000 copies/mL) increased from 50% to 65% (p=<0.001) at 12 months.

Interpretation

Community-based HTC in rural South Africa and Uganda achieved high testing coverage and linkage to care. Among those eligible for ART, a high proportion initiated ART and achieved viral suppression, indicating high adherence. Implementation of this HTC approach by existing community health workers in Africa should be evaluated to determine effectiveness and costs.

Key Words or Phrases: Community-based HIV testing and counseling (HTC), home HTC, point-of-care CD4, linkage to care, HIV prevention and care, HIV infectiousness, community viral load

Introduction

Thirty five million people live with HIV worldwide, 80% of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has high efficacy in reducing HIV associated morbidity and mortality, and transmission of HIV to susceptible partners.2–5 Ecological studies also show a decrease in population-level HIV incidence associated with increased coverage of ART.6 Knowledge of HIV serostatus is the cornerstone of linkage to treatment and prevention, but the proportion of all persons tested in the last year in South Africa and Uganda remains low – between 20% and 43% - compared to the recommendation of annual testing for HIV negative persons in high HIV prevalence areas.7–10 Further, in addition to testing, major challenges in the continuum of care from identification and linkage of HIV positive persons to care, ART uptake, and adherence exist such that in sub-Saharan Africa 25% of HIV positive persons were estimated to be virally suppressed on ART.11–13 Mathematical models suggest that viral suppression in a high proportion of HIV positive persons is necessary for ART to achieve substantial declines in HIV incidence and prevalence.14

To achieve clinical and prevention benefits of ART on a population level, effective and efficient strategies to achieve high coverage of HIV testing coupled with linkage of HIV positive persons to care and treatment are urgently needed. Because symptoms of advanced HIV may motivate persons to seek care, voluntary and provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling (HTC) strategies identify HIV positive persons at a late stage.15 In contrast, community-based HTC strategies are better at identifying asymptomatic HIV positive persons who are unaware of their status and HIV positive persons who are not engaged in care.16 Community-based HTC strategies include community campaigns,17 which achieve large numbers of testing in a short period, and home HTC,18,19 through which HIV counseling and testing is provided by lay counselors in homes.20,21 Systematic reviews found that community-based HTC,16 including home HTC,19 were acceptable and resulted in high uptake of testing. In addition, studies have demonstrated high linkage to care16 and viral suppression over 6 months.18 However, the sample size for these initial studies were small and larger scale feasibility studies demonstrating viral suppression, the main predictor of HIV transmission at a population level, are needed.

We conducted a prospective intervention study of community-based home HTC in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and Mbarara, southwest Uganda. Community-based home HTC was implemented with services to facilitate linkage to care including point-of-care CD4 testing for HIV positive persons, referral to local HIV clinics using a study card with the point-of-care CD4 results and lay counselor follow-up visits. The outcomes were linkage to local HIV clinics, ART initiation among those eligible by national guidelines, and viral suppression at 12 months.

Methods

Research Setting and Procedures

The study was conducted from September 2011 to May 2013 in rural communities of 1,000 households in the Mbarara district in southwestern Uganda, and 600 households in the Vulindlela sub-district of KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. The communities were selected based on not being part of prior home HTC or mobile HTC projects, and which have public clinics that offer free HIV care including ART. General population HIV prevalence in KwaZulu-Natal was 28%,8 and in Mbarara was 10%,22 representing high prevalence regions. Two rural and peri-urban settings where HBCT had not been conducted previously were chosen to assess the generalizability of the results to high prevalence settings in East and southern Africa.

A project coordinator at each site led the study teams. The study activities were conducted by five lay counselors in Uganda and three teams, each consisting of a nurse, lay counselor and data collector, in South Africa. Lay counselors are individuals who have not received a college education, but are trained in HIV testing and counseling, and receive training on the study protocol. Community consultation was followed by mobilization activities, including community events and household preparation visits. Community mobilizers informed households about the study, completed household enumeration, identified eligible resident household members and assessed optimal delivery times for home HTC. Resident, defined as spending 2 nights per week at home to exclude persons who spent the majority of their time out of the household for work or other reasons, adults (≥18 years old) were offered HTC, including persons who were aware of their HIV positive status prior to the study to assess their engagement in care.

In a confidential setting, written informed consent was obtained from participants who completed a standardized questionnaire about demographics, sexual behavior, and history of HIV testing using the mobile phone software Mobenzi Researcher™ (Durban, South Africa). Lay counselors conducted HTC with standardized pre- and post-test and risk reduction counseling. Couples HTC was encouraged, but participants could choose to test separately and not disclose their results.

HIV positive persons completed an additional enrollment questionnaire about sexual behavior, HIV testing and knowledge, HIV clinic visits and ART use. HIV positive persons had same day point-of-care CD4 testing at enrollment, which was used in counseling about ART eligibility under national guidelines (CD4 ≤350 cells/μL). HIV positive persons were provided information about local clinics for HIV care, encouraged to visit a local clinic within a month to initiate ART or establish pre-ART care, and provided a clinic referral card with the date and results of their HIV and point-of-care CD4 tests to facilitate assessment of ART eligibility. They were counseled about national ART initiation guidelines, which had changed to CD4 ≤350 cells/μL a few months before the study was launched, and the next steps required to link to care (clinic registration, baseline laboratory tests), and for those eligible, the importance of ART initiation and adherence. As required by local regulatory bodies, participants were compensated for their time with a food parcel in South Africa (approximate value = USD 8) and cash in Uganda (approximate value = USD 2) at the end of the enrollment and follow-up visits regardless of whether they agreed to testing, HIV serostatus, receipt of results, clinic attendance, or ART initiation. Participants did not receive financial incentives to attend the HIV clinic.

One, three, six, nine, and twelve month follow-up visits for HIV positive persons were scheduled; if the participant had private access to a mobile phone and consented, information was collected for voice and/or text message reminders about follow-up visits. Lay counselors administered questionnaires at each visit about risk behavior, clinic visits, ART use, retention in care, and social harms. To confirm uptake of HIV care and ART, lay counselors reviewed clinic cards and medications with the participant, but clinic attendance and ART dispensation were not confirmed with the clinics. The mobile phone software tracked completed surveys and provided a follow-up visit schedule for study staff.

A plasma sample was collected for HIV viral load testing at baseline, month six and month twelve. Counseling about viral load results obtained at baseline and 6 months were provided to participants to support ART adherence or engagement in pre-ART care for participants who had not yet initiated ART.

Laboratory methods

HIV testing was conducted in the home using blood obtained by finger-stick and tested using rapid serologic tests according to national guidelines (in Uganda Determine (Abbott Laboratories) followed by Statpak (Chembio Diagnostics) for confirmation of positive results and Unigold (Trinity Biotech) as a tie breaker, and in South Africa, ABON HIV Rapid test (Alere) and First Response HIV Test (Premier Medical Corporation Ltd) with HIV 1/2 Gold Screening Test (G-Ocean) as a tie breaker, when needed. Point-of-care CD4 testing (Alere, PIMA™) was conducted in the home using a finger-stick specimen. Plasma was obtained in the home and transported to the reference laboratory for HIV viral load testing by polymerase chain reaction (Roche Taqman Ampliprep with a limit of detection of 20 copies/mL).

The study protocol received ethical approval from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division, the Ugandan National HIV/AIDS Research Committee, and the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Research staff completed surveys during the home visits using Mobenzi software (Durban, South Africa). Data were encrypted on the mobile phone and uploaded to a secure server daily. To ensure robustness of the data collection and data quality, weekly data entry checks were conducted to query unexpected values and check data entry. For CD4 count results, values from the point-of-care CD4 machine log were compared to the results entered into the mobile phones. For assay quality assurance, 10% of rapid HIV tests and point-of-care CD4 tests were confirmed by laboratory based ELISA and flow cytometry, respectively.

Baseline characteristics at enrollment and the uptake of testing and linkage to care, including ART, during follow-up were described by summary statistics. For continuous variables (i.e., age and CD4 cell count), medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were calculated. We assumed that missing values indicated that participants did not link to care or initiate ART. Time to first clinic visits and ART initiation from the baseline enrollment visit were estimated by Kaplan-Meier plots, stratified by whether HIV positive persons were aware of their HIV infection prior to home HTC. For the Kaplan-Meier plots, participants who did not complete a follow-up visit were censored at that visit. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify predictors of visiting an HIV clinic and ART initiation by 12 months among HIV positive persons not on ART at baseline. The potential predictors considered included socio-demographic variables, CD4 count and partner characteristics and the level of significance for the analysis was set at 0.05. The analyses for time to clinic visit and ART initiation excluded persons who reported being on ART at baseline.

To compare changes in binary outcomes (condom use, clinic visit, ART uptake, proportion with viral load <1,000 copies/mL, reported symptoms) between baseline and 12 months, McNemar’s test was used23 and the paired t-test was used to calculate p-values for continuous outcomes (number of sex partners, viral load). Viral suppression was defined as HIV viral load <1,000 copies/mL. The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.3.

Role of the funding source

The study sponsors had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; writing of the report; or in the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Enrollment characteristics

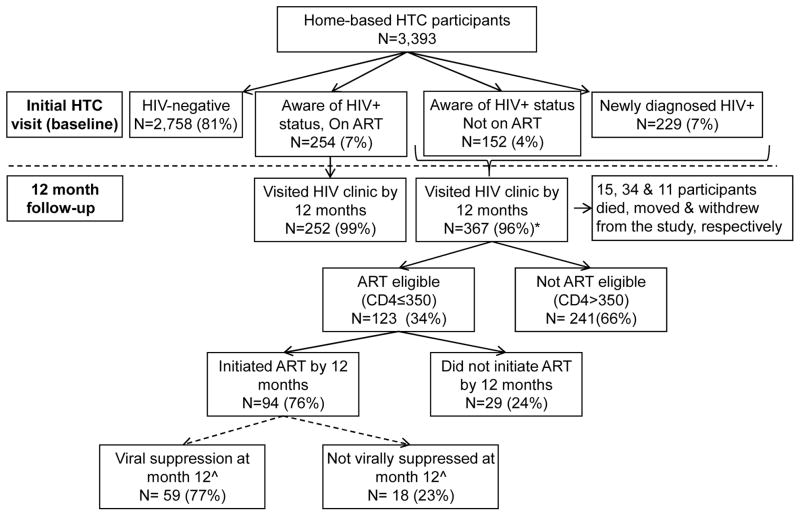

Of the 1,600 households within the study communities, 1,549 households were enumerated (554 in South Africa and 995 in Uganda); 51 households were not enumerated because no-one was at home at the time of the census. Of the 3,545 resident adults identified during the household enumeration, 3,393 (96%) provided informed consent and were tested for HIV, of whom 58% were female. Of the remaining 114, 99 (3%) refused testing, 1 participant was not able to consent, and 14 were not in the home when HTC visits were conducted (Table 1). A total of 635 HIV positive persons (19%) were identified at the baseline HTC visit, of whom 229 (36%) were newly identified (Figure 1). HIV prevalence among women and men in Uganda was 12% and 9%, respectively, and in South Africa was 36% and 24%, respectively.

Table 1.

Enrollment characteristics of adults approached through home HIV testing and counseling (HTC) in South Africa and Uganda

| Total | South Africa | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Households enumerated | 1549 (100) | 554 (100) | 995 (100) |

| Households with children under 18 years | 1174 (76) | 407 (73) | 767 (77) |

| Household head enrolled | 1320 (85) | 435 (79) | 885 (89) |

| Female headed household | 644 (49) | 337 (77) | 307 (35) |

| Adults living in households | 3545 (100) | 1295 (100) | 2250 (100) |

| Adults not present at HBCT visit | 14 (0) | 11 (1) | 3 (0) |

| Adults who refused HIV testing | 99 (3) | 12 (1) | 87 (4) |

| Adults not able to consent | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Adults consented and tested | 3393 (96) | 1272 (98) | 2121 (94) |

| Adults who received HIV test results (% of tested) | 3393 (100) | 1272 (100) | 2121 (100) |

| Male | 1424 (42) | 479 (38) | 945 (45) |

| Female | 1969 (58) | 793 (62) | 1176 (55) |

| First time tested | 1383 (41) | 386 (30) | 997 (47) |

| HIV-infected adults (% of tested/received results) | 635 (19) | 403 (32) | 232 (11) |

| Male (% of tested males) | 201 (14) | 115 (24) | 86 (9) |

| Female (% of tested females) | 434 (22) | 288 (36) | 146 (12) |

| HIV-infected pregnant females (% of HIV+females) | 15 (3) | 9 (3) | 6 (4) |

| Newly identified HIV infection (% of positives) | 229 (36) | 117 (29) | 112 (48) |

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

* Three participants did not have a CD4 count result. ^Because viral suppression is most meaningful for those who initiated ART at least 3 months prior to testing, the proportion with viral suppression is shown for those who initiated ART by month 9 (N=77)

Baseline characteristics of HIV positive participants

Of the 635 HIV positive participants, the median age was 34 years (quartile 1 (Q1) – quartile 3 (Q3): 27–43 years) and 68% were female (Table 2). A total of 229 (36%) were newly diagnosed, 152 (24%) were previously diagnosed with HIV but not on ART, and 254 (40%) were on ART at baseline. Of the 406 HIV positive persons who reported that they knew they were HIV positive from previous testing, 263 reported a date of initial HIV diagnosis, with a median time since initial HIV diagnosis of 40 months (Q1-Q3: 16–71 months). Among the 254 persons on ART, 80% reported a CD4 count test in the last 12 months. Of the 152 HIV positive previously diagnosed persons not on ART, 57% had had a CD4 count measured in the last 12 months and 34% were eligible for ART. Among the 381 HIV positive persons not on ART, 33% were ART eligible by national guidelines (CD4 count ≤350 cells/μL). The median CD4 count among HIV positive participants not on ART was 456 cells/μL (Q1-Q3: 288–628 cells/μL) (Table 2). Of the 239 participants who reported being on ART at baseline, 216 (90%) were virally suppressed (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 635 HIV positive participants identified through home HIV testing and counseling (HTC) in South Africa and Uganda

| Characteristic | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median (quartile 1 (Q1) - quartile 3 (Q3)): 34 (27–42) | |

| Age group ≤30 | 238 (37) | |

| Age group >30 | 397 (63) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 201 (32) | |

| Female | 434 (68) | |

| Education | ||

| Primary or less | 266 (42) | |

| Secondary or more | 369 (58) | |

| Employed | 280 (44) | |

| Cohabiting | 207 (33) | |

| Sexually active | 488 (77) | |

| Number of current sex partners | Median (min, max): 1 (0, 6) | |

| Condom use with last sex act | 272 (43) | |

| Number of children | Median (min, max): 1 (0, 8) | |

| 0 | 277 (46) | |

| 1–3 | 294 (48) | |

| >3 | 37 (6) | |

| On ART at baseline | 254 (40) | |

| CD4 count (cells/ul)# | Median (Q1–Q3): 456 (288–628) | |

| CD4 count category# | ||

| ≤200 cells/ul | 47 (12) | |

| 201–350 cells/ul | 79 (21) | |

| 351–500 cells/ul | 91 (24) | |

| >500 cells/ul | 161 (43) | |

| Reported knowledge of partner HIV status prior to couples counseling and testing | ||

| Yes* | 203 (32) | |

| No^ | 88 (14) | |

| Don’t know | 280 (44) | |

| Refused | 64 (10) |

Note: 12 participants did not respond to the number of sex partners, 3 participants are missing a CD4 value, 2 are missing HIV symptoms.

CD4 count for participants not on ART.

The answer ‘yes’ includes 30 participants who responded ‘I think so.’

The answer ‘no’ includes 28 participants who answered ‘I don’t think so.’

Table 3.

Change in HIV viral load from study enrollment to the 12 month follow-up visit

| Mean (SD) HIV viral load (log10 copies/mL) | Suppressed viral load (<1000 copies/mL), n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N* | Baseline^ | Month 12 | Change | p-value** | Baseline^ | Month 12 | Change | p-value** | |

| All HIV+ participants | 570 | 2.95 (1.57) | 2.40 (1.57) | −0.54 | <0.001 | 287 (50) | 370 (65) | 15% | <0.001 |

| Men | 173 | 3.28 (1.65) | 2.47 (1.61) | −0.81 | <0.001 | 78 (45) | 113 (65) | 20% | <0.001 |

| Women | 397 | 2.80 (1.51) | 2.37 (1.56) | −0.43 | <0.001 | 209 (53) | 257 (65) | 12% | <0.001 |

| HIV+ participants not on ART at baseline | 331 | 3.86 (1.25) | 2.93 (1.65) | −0.93 | <0.001 | 71 (21) | 161 (49) | 27% | <0.001 |

| HIV+ participants on ART at baseline | 239 | 1.68 (0.97) | 1.68 (1.12) | −0.01 | 0.938 | 216 (90) | 209 (87) | −3% | 0.23 |

| ART eligible (CD4 ≤350), including HIV+ who reported ART at baseline | 194 | 3.43 (1.72) | 2.26 (1.61) | −1.17 | <0.001 | 77 (40) | 135 (70) | 30% | <0.001 |

| ART eligible (CD4 ≤350), excluding HIV+ who reported ART at baseline | 114 | 4.49 (1.13) | 2.53 (1.73) | −1.96 | <0.001 | 9 (8) | 70 (61) | 54% | <0.001 |

N indicates the number in the analysis. For the viral load analysis among all HIV+ participants, this includes the 570 participants who had plasma viral load measured at both baseline and 12 months.

Baseline visit is the home-based HCT visit at study enrollment.

McNemar’s test was used to calculate the p-value for binary outcomes and the paired t-test was used to calculate the p-value for continuous outcomes.

Most (77%) of the HIV positive partners reported being sexually active, with a median number of current partners of 1 (min=0, max=6), and 43% reported condom use with the last sex act. HIV positive participants who reported an HIV positive partner were more likely to report condom use at last sex act (67%) compared to those who reported an HIV negative partner or partner of unknown status (33%) (p<0.0001). At the baseline home HTC visit, 44% of HIV positive persons reported that they did not know their partner’s HIV status, 32% reported knowing their partner’s HIV status prior to couples HTC.

Changes in linkage to care, ART initiation and viral suppression by 12 months

Study retention at 12 months was 90%. During follow-up, 15 participants died, 34 moved, and 11 withdrew. The median number of study visits to the home required to conduct each visit was 1 (Q1-Q3: 1–2; range: 1 – 14). If participants did not test at the initial HTC visit, or visit the clinic, or initiate ART if eligible at baseline, the median number of study visits was 2 (Q1-Q3: 2–3), 4 (Q1-Q3: 2–6), and 5 (Q1-Q3: 5–6), respectively.

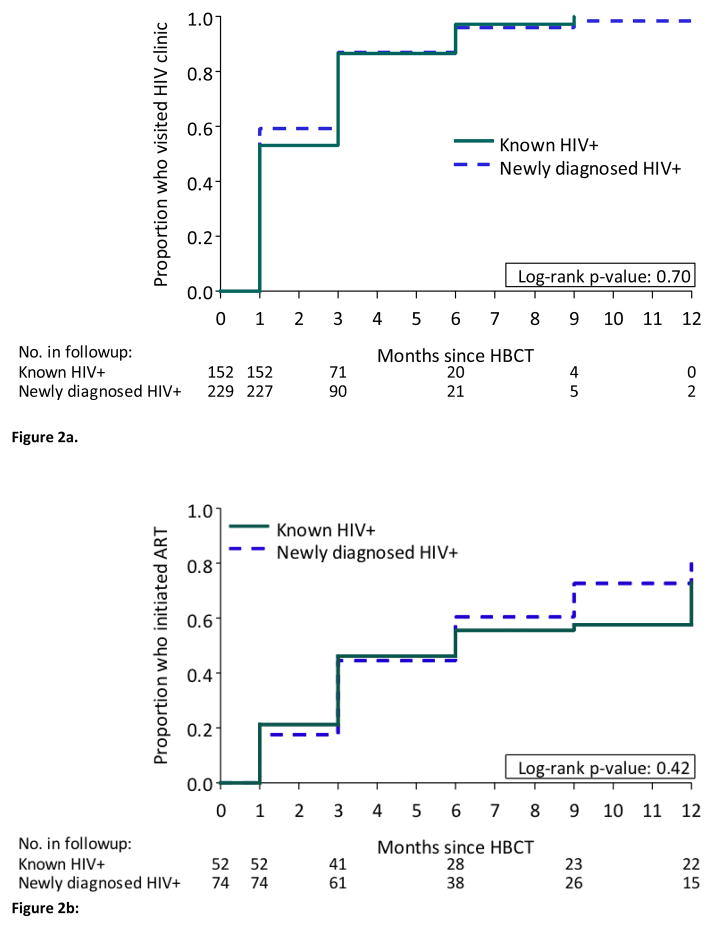

By month 12, 367 (96%) of 381 HIV positive participants not on ART at baseline had visited an HIV clinic (Figure 1). The cumulative probability of visiting a clinic among HIV positive persons not on ART at baseline was 57% by month 1, 86% by month 3 and 97% by month 6; there was no difference in uptake of clinic visits by whether the participants was newly diagnosed or had previously tested positive for HIV (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Uptake of clinic visits among participants not on ART at baseline, by previous knowledge of HIV status before home-based HIV testing

Figure 2b: ART initiation among those eligible and reported not being on ART at baseline, by previous knowledge of HIV status before home-based HIV testing

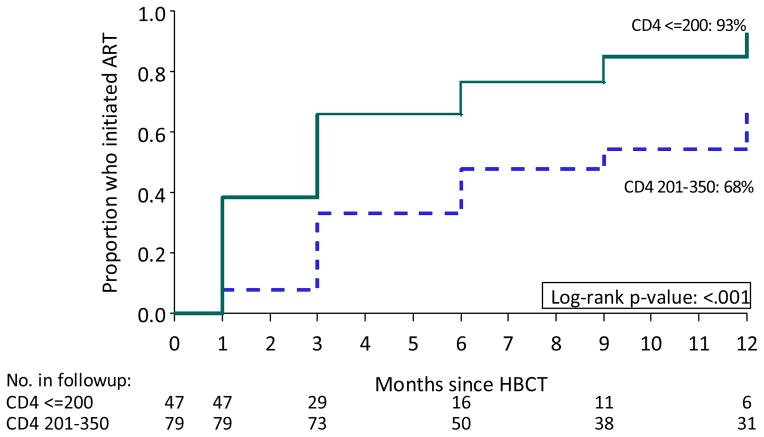

The cumulative probability of ART initiation by 12 months was 76% among participants not on ART at baseline among those who met national ART initiation guidelines (CD4≤350 cells/μL) (Figure 1), with no difference by whether participants were newly diagnosed or knew their HIV positive status at baseline (Figure 2b). Overall, significant differences in ART uptake by month 12 was seen by CD4 count strata; ART uptake was 93% for those with CD4 count ≤200 cells/μL, and 68% for those with CD4 count 201–350 cells/μL (p<0.001) (Figure 3). The most common reason reported by participants for not initiating ART despite being eligible by the POC CD4 result was “I was told I was not eligible” when assessed at the HIV clinic in South Africa (64%) and Uganda (22%), and delays due to the clinics repeating CD4 count or waiting for 3 officially required visit appointments for ART initiation (46%) in Uganda. A small proportion (18%) of 255 participants with a baseline CD4 count >350 cells/μL initiated ART by month 12, due to pregnancy, diagnosis of tuberculosis, or provider choice. Multivariable regression did not identify predictors for visiting an HIV clinic and only baseline CD4 count ≤350 cells/μL was identified as a significant predictor for ART initiation by 12 months (see Supplementary tables).

Figure 3.

ART uptake by CD4 count strata among participants not on ART at enrollment

Overall, among the 570 HIV positive participants who had viral load measures available at baseline and 12 months, regardless of ART eligibility or initiation, the population mean HIV viral load decreased by 0.54 log10 copies/mL at 12 months (p=<0.001) (Table 3). Among the 114 participants who were not on ART but eligible by national guidelines at baseline (CD4≤350 cells/μL) mean HIV viral load decreased by 1.96 log10 copies/mL (p=<0.001) (N=114) and 61% were virally suppressed by 12 months. When restricted to the 77 who had initiated ART by month 9 and were on ART for three months before the 12 month viral load measurement, 77% of those were virally suppressed. Among HIV positive participants who were eligible for ART by national guidelines based on a baseline CD4 count ≤350 cells/μL, the percentage with HIV viral load <1,000 copies/mL increased from 40% to 70% (p=<0.001). Notably, of the 381 participants not on ART at enrollment, 81 (21%) had baseline viral load <1,000 copies/mL despite reporting that they were not currently on ART.

By the month 12 visit, among the 181 HIV positive persons who reported a partner within the household, 91% reported that they had disclosed their status to their partners. Counselors provided couples counseling and facilitated disclosure but participants could choose to disclose without the counselor present. There were no reported cases of study related social harm during the study. Specifically, there were no reports of partnership separation, unintended disclosure, gender-based violence and stigma.

Discussion

This study evaluated community-based HTC and linkage to HIV care strategies in two rural, high HIV prevalence communities in East and Southern Africa (Mbarara, Uganda, and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). We adapted the home HTC approach19 by incorporating point-of-care CD4 testing and referral to local HIV clinics to facilitate linkage, and lay counselor follow-up visits using a mobile phone software platform to address drop-off in the HIV continuum of care.24 The most important outcome metrics for HIV testing programs are the proportions tested, linked to HIV care, and viral suppression among those who initiate ART.25 Among adult household residents, 96% were tested for HIV achieving widespread knowledge of serostatus (including among asymptomatic individuals), 19% of whom were HIV positive, with 97% linked to HIV care by 12 months. The program successfully promoted ART initiation following national guidelines, with 76% of those eligible initiating ART by 12 months. Importantly, the rate of HIV disclosure was high and no social harms were reported. This study demonstrates that community-based HTC with lay counselors providing point-of-care CD4 testing, referrals and follow-up achieves high coverage in linkage to care, ART initiation, and viral suppression, which is necessary to achieve a reduction in HIV incidence for ‘treatment as prevention’.

As a key outcome measure of the prevention impact of home HTC and HIV care linkages with ART initiation based on national guidelines, we compared HIV plasma viral load at baseline and 12 months after HIV testing through the HTC program. Notably, the proportion of HIV positive persons eligible for ART at baseline, who were virally suppressed increased to 70% by 12 months after HTC. The decrease in mean plasma HIV viral load was 0.54 log10 copies/mL across all HIV positive persons; extrapolating from modeling results, this magnitude of reduction in plasma viral load across all the HIV positive persons identified through home HTC is estimated to be associated with a 37% reduction in transmission.26 HIV clinic attendance was almost universal but ART uptake among participants was lower among those newly eligible for ART (CD4≤350 cells/μL), likely due to a lag in implementing the new ART guidelines to CD4≤350 cells/μL, which changed a few months before the study was initiated. Participants reported structural barriers to ART initiation including HIV clinics repeating CD4 counts and requiring multiple visits before ART initiation, which need to be addressed. Clinic providers and counselors need to be familiar with changes in ART initiation guidelines and be able to provide effective counseling messages about the benefits of ART for asymptomatic persons.

Mathematical models of HIV transmission in KwaZulu-Natal suggest that home HTC every four years could have a sustained impact on the epidemic, if associated with behavior change, high uptake of ART uptake and medical male circumcision.27 In order to streamline and scale up implementation of this model, follow-up visits could focus on the HIV positive participants who were not on ART at baseline and who have not linked to care by three months, since uptake of linkage to clinics was almost 60% by month one. Home HTC could utilize an existing cadre of community health workers in South Africa, Uganda and many other African countries to deliver integrated health care to communities.28 This decentralized model of health care delivery, community-based HTC, using point-of-care CD4 testing to facilitate same day ART eligibility assessment and mobile phones with software to facilitate follow-up visits has the potential to increase ART uptake and achieve its treatment as prevention potential. As simpler and less expensive viral load tests become available, viral load monitoring of persons on ART could be added to assess ART adherence and provide targeted adherence counseling.

The main limitation of the study was the lack of a comparator for the intervention. However, approximately half of persons were tested in the past year in a South Africa national survey from 20128 and in the standard HIV testing arm in a 2009–2010 study in Sisonke, KwaZulu Natal7 which provide relevant benchmarks. In the South Africa national survey ART was detectable in the plasma of 31% of participants, which is comparable to the 37% viral suppression found among all HIV positive persons regardless of ART use at baseline in our study. Limitations of our study included delivery of a package of interventions so the incremental contribution of each individual strategy (home HTC, point-of-care CD4 testing, and follow-up visits) for increasing linkage to HIV clinics, ART uptake, and viral suppression could not be assessed. We did not assess the impact of mobility as household members who were not resident, such as migrant workers, were excluded which could change our estimation of community-level impact. Clinic visits and ART initiation in follow-up visits were confirmed by examination of the clinic card and ART medication bottles, as clinic electronic health records were not available to verify clinic attendance or pharmacy prescriptions. Samples were not stored so we were not able to measure antiretrovirals in the plasma of the 21% of HIV positive persons who were virally suppressed at baseline but reported not being on ART. They may not have wanted to disclose their ART use or not understood the question. Lastly, due to lack of storage of samples, we were not able to test for HIV resistance among HIV positive persons who reported being on ART but had a detectable viral load.

In summary, community-based home HTC in rural South Africa and Uganda achieved almost universal coverage of HIV testing, and identified HIV positive persons, both those who were unaware of their status and aware but not engaged in care. The intervention was successful in two countries, supporting the generalizability of the approach. Many of the HIV positive persons were asymptomatic with an average CD4 count of 456 cells/μL. They would benefit from HIV care linkage, counseling and ART, with a higher proportion eligible for ART since South Africa and Uganda have recently increased their CD4 threshold for ART initiation to CD4≤500 cells/μL, following the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Point-of-care CD4 testing for HIV positive persons at the initial visit with counseling about ART eligibility and lay counselor follow-up achieved almost universal linkage to HIV care by 12 months. Within 12 months, three-quarters of those eligible for ART by national guidelines had initiated ART, and almost 80% were virally suppressed. Importantly, the significant reduction in plasma HIV viral load at a community level indicates that ART may have a prevention benefit by decreasing onward HIV transmission. Evaluation of the incremental benefits and cost-effectiveness of these strategies in diverse settings should be undertaken to inform public health policy.

Research in Context

Systematic Review

Community-based HIV testing and counseling (HTC) strategies include community campaigns,17 which achieve large numbers of testing in a short period, and home HTC,18,19 through which HIV counseling and testing is provided by lay counselors in homes.20,21 We searched Pubmed and EMBASE for community-based HTC studies published between January 1st, 2000, and June 12th, 2014, with the terms HIV and Africa South of the Sahara and (mass screening OR testing OR screen OR diagnosis OR counseling). We identified 1,004 abstracts for review, including two recent systematic reviews.16,19 Systematic reviews found that community-based HTC,16 including home HTC,19 were acceptable and resulted in higher uptake of testing compared to facility based testing (relative risk [RR] = 10.65 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6.27–18.08).16 Also, the community-based HTC review found a trend towards reduced HIV incidence (RR=0.86 (95% CI 0.73–1.020). Overall the data on linkage to HIV treatment services were limited.16 A few studies have demonstrated high linkage to care16 and viral suppression over 6 months.18 However, the sample sizes for these initial studies were small and larger scale feasibility studies demonstrating viral suppression, the main predictor of HIV transmission at a population level, are needed.

Interpretation

This study adds to the evidence on the effectiveness of community-based HTC to identify and link HIV positive persons to care. Also, the impact of a package of community-based interventions to strengthen testing and linkages to care on population viral load at 12 months in southern Africa is a novel contribution. The strategy of lay-counselors providing home HTC, point-of-care CD4 testing, and follow-up visits resulted in high uptake of testing (96%), linkage to are for HIV positive persons (97%), ART initiation (76%) among those eligible, and viral suppression (77%). The intervention was successful in two countries, South Africa and Uganda, supporting the generalizability of this approach. Most encouraging, the proportion of HIV positive persons in the community with viral suppression increased significantly at 12 months. These community-based HTC approaches that involve lay-counselors and work within existing health care systems have the potential to deliver widespread HIV testing, prevention and care. Implementation of this HTC approach by existing community health workers in Africa should be evaluated to determine effectiveness and costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 5 R01 AI083034, 3 R0 AI083034-02S2 and NIH Directors Award RC4 AI092552. RVB acknowledges funding from NCATS/NIH (KL2 TR000421) and the Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR)/NIH (P30 AI027757).

We are grateful to the study volunteers for their participation in this study. We acknowledge the outstanding work of the ICOBI, HSRC and UW study teams.

Footnotes

Regulatory: All participants provided written informed consent. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board, the Ugandan National HIV/AIDS Research Committee, and the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee approved this study.

- Barnabas R, van Rooyen H, Tumwesigye E, Murnane P, Humphries H, Turyamureeba B, Krows M, Hughes JP, Baeten J and Celum C. Uptake of ART is lower among HIV positive persons with higher CD4 counts despite engagement in care in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and Mbarara, district-Uganda. HIV Treatment as Prevention; April 22–25, 2013; Vancouver, Canada.

- Barnabas, R., E. Tumwesigye, H. Van Rooyen, P. Murnane, B. Turyamureeba, H. Humphries, M. Krows, J. Hughes, J. Baeten and C. Celum. Study Updates: Combination Trials in South Africa and Uganda. HIV Treatment as Prevention. April 22–25, 2013. Vancouver, Canada.

- Barnabas, R., R. Ying, H. van Rooyen, P. Murnane, J. Hughes, J. Baeten and C. Celum. “Use of HIV viral-load suppression to estimate the effect of community-wide home-based HIV counselling and testing and linkage to antiretroviral therapy on HIV incidence in South Africa: a mathematical modelling analysis.” Cell-The Lancet: What Will it Take to Achieve an AIDS-free World. A translational medicine conference on HIV research. The Lancet 382: S6. November 3–5, 2013. San Francisco, CA.

- Barnabas R, van Rooyen H, Tumwesigye E, Humphries H, Turyamureeba B, Murnane P, Hughes JP, Baeten J and Celum C. Community-based HCT studies demonstrate high up-take of HIV testing & successful linkages to care in South Africa & Uganda. ICASA; December 7–11, 2013; Cape Town.

- Barnabas R, Van Rooyen H, Tumwesigye E, Krows M, Murnane P, Humphries H, Turyamureeba B, Hughes JP, Baeten J, Celum C. Community HIV testing and linkage to care reduces population viral load in South Africa and Uganda CROI; March 2014; Boston

Contributors: RB oversaw the implementation of the study and wrote the first draft of the paper, which was revised by all authors. All authors contributed to design and execution of the study, as well as to the interpretation of findings. PM did the statistical analysis with input from RB, JB, JH and CC. All the authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Declaration of interests: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2013 http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf.

- 2.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mills EJ, Bakanda C, Birungi J, et al. Life expectancy of persons receiving combination antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries: a cohort analysis from Uganda. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(4):209–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitahata MM, Gange SJ, Abraham AG, et al. Effect of early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy for HIV on survival. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360(18):1815–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanser F, Barnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Science. 2013;339(6122):966–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1228160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty T, Tabana H, Jackson D, et al. Effect of home based HIV counselling and testing intervention in rural South Africa: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f3481. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behavior Survey, 2012. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uganda AIDS Commission. Global AIDS response progress report: Uganda Jan 2010–Dec 2012. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda AIDS Commission; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: A turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2011;8(7):e1001056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH. 2012;17(12):1509–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH. 2010;15 (Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassett IV, Giddy J, Nkera J, et al. Routine voluntary HIV testing in Durban, South Africa: the experience from an outpatient department. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2007;46(2):181–6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31814277c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS medicine. 2013;10(8):e1001496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamie G, Kwarisiima D, Kabami J, et al. Outcomes in a routine linkage-to-care strategy and an enhanced strategy with accelerated ART Start; community-based HIV testing and point-of-care CD4: rural Uganda. 19th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 2012 March 5–8. Seattle, WA; 2012. p. Abstract 1134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Rooyen H, Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, et al. High HIV testing uptake and linkage to care in a novel program of home-based HIV counseling and testing with facilitated referral in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2013;64(1):e1–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31829b567d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabapathy K, Van den Bergh R, Fidler S, Hayes R, Ford N. Uptake of home-based voluntary HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2012;9(12):e1001351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molesworth AM, Ndhlovu R, Banda E, et al. High Accuracy of Home-Based Community Rapid HIV Testing in Rural Malawi. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(5):625–30. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f98628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tumwesigye E, Wana G, Kasasa S, Muganzi E, Nuwaha F. High uptake of home-based, district-wide, HIV counseling and testing in Uganda. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2010;24(11):735–41. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Health (Uganda) and ORC Marcro. Uganda HIV/AIDS Sero-behavioural survey 2004–2005. Claverton, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNemar Q. Note on the sampling error of the difference between correlated proportions or percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12(2):153–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNairy ML, El-Sadr WM. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV transmission: What will it take? Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertozzi S. PEPFAR/Global Fund at 10 years: Past, Present, and Future. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingappa JR, Hughes JP, Wang RS, et al. Estimating the impact of plasma HIV-1 RNA reductions on heterosexual HIV-1 transmission risk. PloS one. 2010;5(9):e12598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alsallaq RA, Baeten JM, Celum CL, et al. Understanding the potential impact of a combination HIV prevention intervention in a hyper-endemic community. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e54575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uwimana J, Zarowsky C, Hausler H, Jackson D. Training community care workers to provide comprehensive TB/HIV/PMTCT integrated care in KwaZulu-Natal: lessons learnt. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.