Abstract

Sphingolipids are a highly conserved lipid component of cell membranes involved in the formation of lipid raft domains that house many of the receptors and cell-to-cell signaling factors involved in regulating cell division, maturation, and terminal differentiation. By measuring and manipulating sphingolipid metabolism using pharmacological and genetic tools in Caenorhabditis elegans, we provide evidence that the synthesis and remodeling of specific ceramides (e.g., dC18:1–C24:1), gangliosides (e.g., GM1–C24:1), and sphingomyelins (e.g., dC18:1–C18:1) influence development rate and lifespan. We found that the levels of fatty acid chain desaturation and elongation in many sphingolipid species increased during development and aging, with no such changes in developmentally-arrested dauer larvae or normal adults after food withdrawal (an anti-aging intervention). Pharmacological inhibitors and small interfering RNAs directed against serine palmitoyl transferase and glucosylceramide synthase acted to slow development rate, extend the reproductive period, and increase lifespan. In contrast, worms fed an egg yolk diet rich in sphingolipids exhibited accelerated development and reduced lifespan. Our findings demonstrate that sphingolipid accumulation and remodeling are critical events that determine development rate and lifespan in the nematode model, with both development rate and aging being accelerated by the synthesis of sphingomyelin, and its metabolism to ceramides and gangliosides.

Keywords: Longevity, Oxidative stress, Ceramide, Gangliosides, Sphingomyelin

1. Introduction

Across a range of phyla and species there is, with few exceptions, an association between developmental rate and lifespan such that organisms which develop rapidly also age rapidly (Ricklefs, 2006). Moreover, environmental factors that slow development rate, such as food deprivation, can extend lifespan as has been demonstrated for species ranging from the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) (Johnson et al., 1984; Kimura et al., 1997; Mattison et al., 2003; Mukhopadhyay and Tissenbaum, 2007). Consistent with the idea that the mechanisms that regulate development and aging overlap, activation of insulin-like pathways have been shown to increase anabolic processes and accumulation of proteins and lipids; whereas, calorie restriction and germ-line stem cell ablation decrease lipid accumulation via activation of triglyceride lipases in C. elegans and Drosophila melanogaster (Kimura et al., 1997; Hsin and Kenyon, 1999; Tatar et al., 2003; Gami and Wolkow, 2006). Similar mechanisms may regulate lifespan in humans because abnormalities in insulin signaling and associated dyslipidemia are involved in several major disorders that reduce lifespan including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Straczkowski and Kowalska, 2008; Mooradian, 2009).

Sphingolipids are present in high amounts in membrane microdomains (i.e., lipid rafts), which also contain receptors and associated signaling proteins that regulate responses of cells to a variety of environmental signals (Merrill and Jones, 1990). Sphingolipid synthesis is initiated by serine palmitoyl-transferase (SPT)-mediated formation of 3-dihydrosphinganine from serine and palmitoyl-CoA, followed by the sequential production of sphingosine, ceramide, and sphingomyelin (Gulbins and Kolesnick, 2003) (Fig. 1A). In response to the activation of cell surface receptors for growth factors and cytokines, sphingomyelinases (SMases) cleave sphingomyelin to generate ceramides and other bioactive metabolites including sphingosine-1-phosphate and gangliosides (Hannun and Obeid, 2008). C. elegans express two SMases that are similar to mammalian acidic SMase (Lin et al., 1998). Analyses of tissue samples from mice and human subjects have suggested an association between the accumulation of sphingomyelin and ceramides and the processes of normal aging and age-related diseases that limit lifespan (Lightle et al., 2000; Cutler et al., 2004; Kolesnick and Tilly, 2005; Venable et al., 2006). Roles for lipids in development, reproduction, and aging are suggested by data showing that changes in the cholesterol and fatty acid composition of the diet influence development and lifespan in C. elegans (Gerisch et al., 2001; Watts and Browse, 2006), and that genetic and pharmacological inhibition of glycosphingolipid synthesis and phosphorylcholine metabolism impairs development and fertility in C. elegans (Lochnit et al., 2005). In addition, it was recently reported that pharmacological inhibition of SPT increases yeast lifespan by a mechanism involving reduced activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and activation of AMP kinase (Huang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013). Recent findings also suggest the involvement of ceramide accumulation in age-related apoptosis of germ cells in mice (Kolesnick and Tilly, 2005), and the accumulation of certain sphingolipids in neurodegenerative diseases in humans (Cutler et al., 2002, 2004).

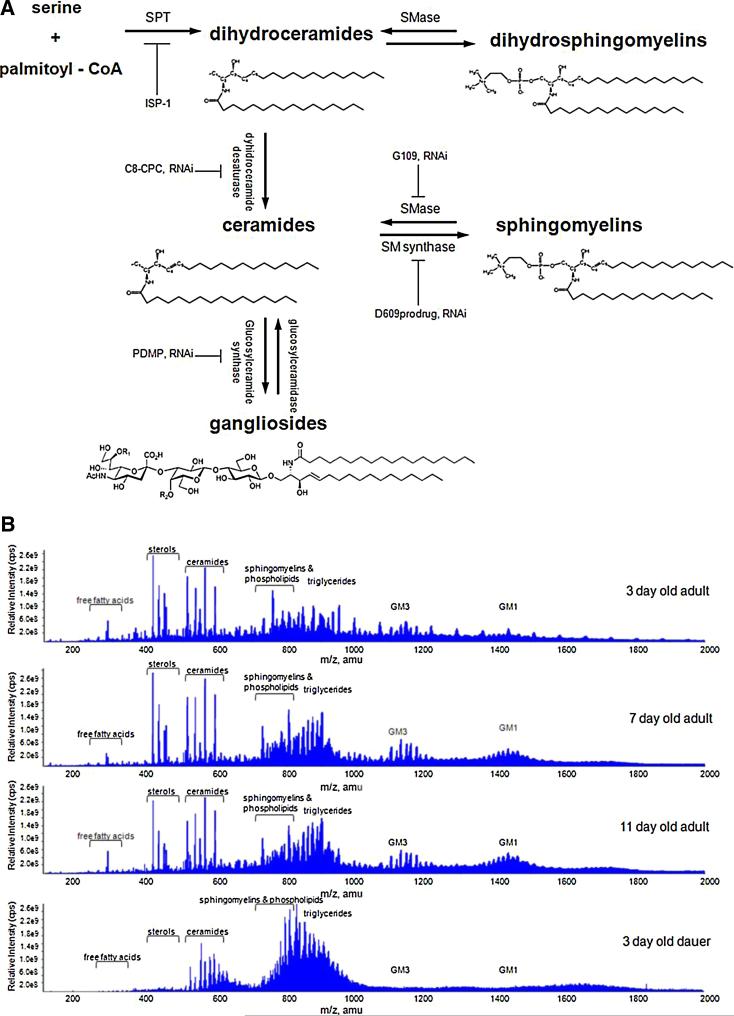

Fig. 1.

Sphingolipid metabolic pathways and shotgun lipidomic analysis of aging and dauer arrested C. elegans.

(A) Biochemical pathways for the synthesis and metabolism of ceramides, gangliosides, and sphingomyelins. Drug- and RNAi-targeted enzymes evaluated in this study are indicated. (B) Representative tandem mass spectrograms showing Q1 detection of all lipid species from 150 to 2000 Daltons [m/z (mass/charge), amu (atomic mass units)] in samples from adult C. elegans of the indicated ages, and 3 day old dauer larvae. Note the increasing amounts of gangliosides GM1 and GM3 in adults compared to dauers, and with advancing age in adults.

Here we provide evidence that sphingolipid metabolism plays a key role in regulating development and aging in C. elegans. We show that levels of GM1 and GM3 gangliosides, and fatty acid chain elongation, and desaturation of ceramides, increase progressively during larval development and throughout adult life. Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis slows development rate, while proportionally prolonging the egg laying period and extending maximum lifespan. These findings suggest that the accumulation and metabolism of sphingolipids strongly influence development rate and lifespan.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. C. elegans strain maintenance and experimental methods

C. elegans strain N2 (wild type, Bristol), daf-2 (e1370), sptl-1(ok1693), and Escherichia coli OP50 were obtained from the University of Minnesota Caenorhabditis Genetics Center collection facility. Egg synchronization was performed by placing 10 gravid 4–7 day-old hermaphrodites in a plate for 6 h. The adult worms were then removed from the plates and 100 μL of heat-killed OP50 E. coli in M9 solution was added. The triglyceride and sphingolipid pathway inhibitors used in this study were: the triglyceride synthase inhibitor C75 (4-methylene-2-octyl-5-oxotetrahydrofuran-3-carboxylic acid; Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); the SPT inhibitor ISP-1 (myriocin, 2S, 3R, 4R, 6E-2-Amino-3, 4-dihydroxy-2-hydroxymethyl-14-oxo-6-eicosenoic acid; Sigma–Aldrich); the dihydro-ceramide desaturase inhibitor C8-CPC (C8-cyclopropenylceramide; Matreya Inc., Pleasant Gap, PA, USA); the ceramidase inhibitor MAPP (D-erythro-MAPP, 1S, 2R-D-erythro-2-N-Myristoylamino-1-phenyl-1-propanol; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA); the glucosyl ceramide synthase inhibitor PDMP (d,l – erythro-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol hydrochloride; Matreya Inc.,); the sphingomyelin synthase inhibitor D609 (calbiochem); and the neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitor epoxyquinone G109 (manumycin A, racemic; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA, USA). All drug inhibitors were solubilized in DMSO and diluted to 30 μM/plate, except as noted in Table S2. The final concentration of DMSO for drug inhibitor and control plates equaled 0.01%. None of the drugs had any effect on the growth of E. coli OP50.

2.2. siRNA constructs and knock out strains

Genomic fragments obtained by PCR were cloned into the vector L4440. The Gene Pairs primer sequences are available at http://cmgm.stanford.edu/kimlab/primers.12-22-99.html and are displayed visually in wormbase (http://www.wormbase.org). Clones are available from MRC geneservice (http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/geneservice/reagents/products/rnai/index.shtml).

Constructs were transformed into HT115 (DE3) and siRNA strains were grown on siRNA nematode NGM agar plates (KD Medical, Columbia, MD) with 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 25 μg/mL carbenicillin, and 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside). Gene-specific knockouts were generated by the C. elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia for the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium (www.celeganskoconsortium.omrf.org); RB1465 [sptl-1 (ok1693)], and RB1579 [sptl-3 (gk662)]. Strains were backcrossed three times and worms screened for specific deletion. Three positive worms were individually used to generate worms for the development and lifespan studies.

2.3. Measurements of developmental rate, fecundity, and lifespan

Development was scored twice per day at 12 h intervals using length and internal complexity for identification. Time zero was started after egg-laying adults were taken off of synchronized plate. The phenotypic changes of F1 eggs treated with drug or siRNA intervention are described in the results section. The progeny from ISP-1 and SPT siRNA treated worms was approximately 24% smaller at each developmental stage, therefore, the size scoring criteria was adjusted proportionally. Seventeen-day-old worms were scored for length and width to determine resulting adult size from each treatment. Nematodes were scored daily for abdominal presence of eggs, and transferred to new plates until they were no longer laying eggs. Survival was scored daily. Missing and bagged animals were excluded from the analyzed data.

2.4. Autofluorescence

The amount of auto-fluorescence was measured using a confocal Axiovert S100 microscope (×10) (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 510 nm. Values were expressed as average pixel intensity for the entire area of the worm.

2.5. Lipid extraction and lipidomic analysis using triple quadropole tandem mass spectrometry

C. elegans eggs, dauers (produced by food starvation and aged for 7 days), and 3, 7, and 11 day-old adult worms were collected in Eppendorf tubes containing M9 solution. After one additional wash with M9 solution, the pellet was used for lipid extraction as described previously (Cutler et al., 2004). Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI/MS/MS) analysis was performed using a Turbo Ion Spray module Sciex API 3000 triple stage quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (ES/MS/MS) operating in the positive mode (Sciex Inc., Thornhill, Ontario, Canada). Samples were injected into the ES/MS/MS for 5 min, and the sum of the total counts under each peak was used to quantify each species. The following standards were used: sphingosine and sphingosine-1-phosphate C18:1, dihydroceramides (C16:0 – C24:1), sphingomyelins (C16:0 – C18:0), phosphatidyl-choline C16:0 – C18:1, phospatidylethanolamine C16:0 – C18:1, phosphatidylglycerol C16:0 – C18:1, phosphatidylserine C16:0 – C18:1, phosphatidylinositol C16:0 – C18:1, and phosphatidic acid C16:0 – C18:1 from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL, USA). Sphingomyelin C20:0 – C24:0 from Sigma–Aldrich. Palmitoyl-lactosyl ceramide C16:0 – C16:0, stearoyl-lactosyl-ceramide C16:0 – C18:0, lignoceryl-glucosyl-ceramide C16:0 – C24:0, lignoceryl-galactosylceramide C16:0 – C24:0, and stearoyl-galactosyl-ceramide-sulfate C18:1 – C24:0, and triacylglyceride palmitic-oleic-stearic (C52, POS) were from Matreya Inc., quantitative values for each species are expressed as relative abundance after normalization to Q1 phosphatidylethanolamine C18:1.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Biochemical data were analyzed by ANOVA and pair wise comparisons were made using a Scheffe’s post-hoc test. Lifespan data were subjected Kaplan–Meier analysis with Log-rank (Mantel–Cox) and Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon tests using Graphpad prism 5.0 software, GraphPad software, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Ceramides, gangliosides, and sphingomyelins accumulate and remodel during normal development and aging

The enzyme SPT catalyzes the initial and rate-limiting step of sphingolipid synthesis, using pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) as a cofactor in the decarboxylating transfer of palmitoyl-CoA onto serine to form sphingosine, which is converted into biologically inert dihydroceramides (Fig. 1A). Dihydroceramides can either be transformed into dihydrosphingomyelin or converted to biologically active ceramides by sphingolipid desaturase. Sphingomyelin is produced by de novo synthesis from ceramide or by desaturation of dihydrosphingomyelin. Ceramides and sphingomyelins are known growth and signaling factors; whereas, their dihydro precursors serve structural roles, such as providing the hydrophobic properties of the skin and eye lens (Yappert et al., 2003). Sphingomyelinases can hydrolyze dihydrosphingomyelin or sphingomyelin resulting in the generation of dihydroceramide and ceramide, respectively; glucosylceramide synthase and subsequent pathway enzymes add sialic acid and sugar residues to ceramide to produce gangliosides (Fig. 1A). Because the types and amounts of ceramides, gangliosides, and sphingomyelins in C. elegans have not previously been characterized, we performed mass spectrometry-based analysis of these lipids in eggs and adults of increasing ages (3, 7, and 11 days old). We also measured lipid levels in dauer larva, which are in an arrested state of development and exhibit negligible aging (Fielenbach and Antebi, 2008). The lipid analyses were performed using methods similar to those of our previous studies in rodent and human brain and spinal cord samples (Cutler et al., 2002, 2004). ES/MS/MS methods were used to identify and quantify a range of lipids including free fatty acids, triglycerides, membrane phospholipids, ceramides, glucosylceramides, gangliosides, and sphingomyelins, with different carbon chain lengths and numbers of unsaturated bonds (Fig. 1B).

Examination of mass spectrograms (lipidomic profiling of 150–2000 Daltons) between eggs, 3, 7, and 11 day-old worms, and dauer larvae, indicated that levels of specific lipid species changed progressively during development and aging; these changes were not seen in developmentally arrested dauers. For example, levels of gangliosides GM1 and GM3 increased progressively during adult life (8.1 fold, p = 0.0357), but were very low in dauer larvae (4.5% vs. 7 day old worms, p = 0.0338) (Fig. 1B and Table S1).

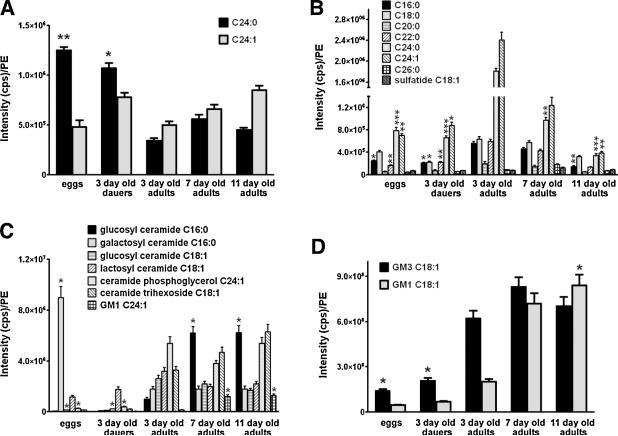

Quantitative lipid profiling of samples prepared from multiple (4–6) batches of eggs, dauer larvae, and 3, 7, and 11 day-old adult worms shows that levels of long-chain dihydroceramide C24:0 (known to function in hydrophobic barrier protection of the epidermis and outer cuticle) were significantly higher in eggs and dauers (3.25 fold, p = 0.0092) compared to adults (Fig. 2A). Levels of the following ceramides were significantly elevated in 3 day-old adults compared to eggs or dauers, and progressively decreased with advancing age (5.23 fold, p = 0.0012): C16:0, C18:0, C22:0, C24:0, and C24:1 (Fig. 2B). In contrast, levels of C20:0 and C26:0 ceramides and sulfatide C18:1 were not affected significantly by developmental stage or age (Fig. 2B). Analysis of additional ceramide species revealed that levels of glucosyl ceramide C16:0, ceramide trihexoside C18:1, and ganglioside GM1 24:1 were very low in eggs and dauers and increased progressively during aging (Fig. 2C). Levels of galactosyl ceramide C16:0, glucosyl ceramide C18:1, and lactosyl ceramide C18:1 were significantly greater in adult worms compared to dauers, but were unaffected during aging (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, levels of galactosyl ceramide 16:0 were 5-fold (p = 0.0164) greater in eggs compared to adults. Levels of gangliosides GM1C18:1 and GM3C18:1 were significantly higher in adults compared to eggs or dauers, and levels of GM1 18:1 were significantly greater in old compared to young adults (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Levels of unsaturated ceramides, and gangliosides GM1 and GM3, increase with advancing age.

Results of quantitative analysis of the indicated dihydroceramides (A), ceramides (B) and gangliosides (C) and (D) in C. elegans eggs, dauer larvae, and adults of the indicated ages. Values are the mean and SEM (n = 4 separate experiments). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to the level of the same lipid in 3 day-old adult worms.

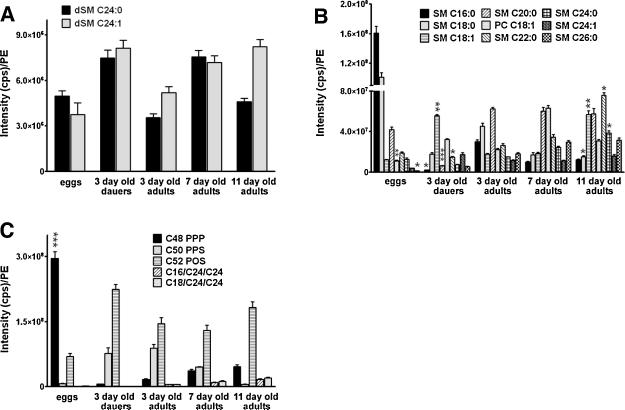

The lipid profile of eggs exhibited relatively high amounts of medium chain (C16:0, C18:0) sphingomyelins and triglycerides, perhaps as a reserve of lipid substrates needed for the rapid growth of embryos; whereas, dauers had the lowest levels of short chain sphingomyelins and triglycerides compared to all other groups tested (Fig. 3). Relative to normally developing worms, dauers also had significantly lower levels of biologically active ceramide, ganglioside, and sphingomyelin species, along with high levels of biologically inert dihydroceramides (Fig. 2A) and dihydrosphingomyelin (Fig. 3A). Overall, the levels of sphingomyelins increased progressively with age, with levels of C18:1, C22:0, and C24:0 being significantly higher in 11 day-old worms compared to young worms (3.2 fold, p = 0.0058). Interestingly, there was significant remodeling of sphingomyelins during adult life; specifically in desaturation (e.g., a change from C18:0 to C18:1) (Fig. 3B) and hydroxylation (Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Levels of sphingomyelins and triglycerides change during development and aging.

Results of quantitative analysis of levels of the indicated dihydrosphingomyelins (A), sphingomyelins (B) and triglycerides (C) in C. elegans eggs, dauer larvae, and adults of the indicated ages. Values are the mean and SEM (n = 4 separate experiments). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 compared to the level of the same lipid in 3 day-old adult worms.

We were able to reliably identify and quantify five triglycerides in C. elegans: C48 PPP, C50 PPS, C52 POS, C16/C24/C24, and C18/C24/C24. The only triglycerides that were affected significantly by age were C16/C24/C24, and C18/C24/C24 which were undetectable in dauers and mirrored the increases in fatty acid chain elongation and desaturation of sphingomyelins that occurred during aging (Fig. 3C).

3.2. Pharmacological inhibition of de novo sphingolipid synthesis slows development and extends functional lifespan

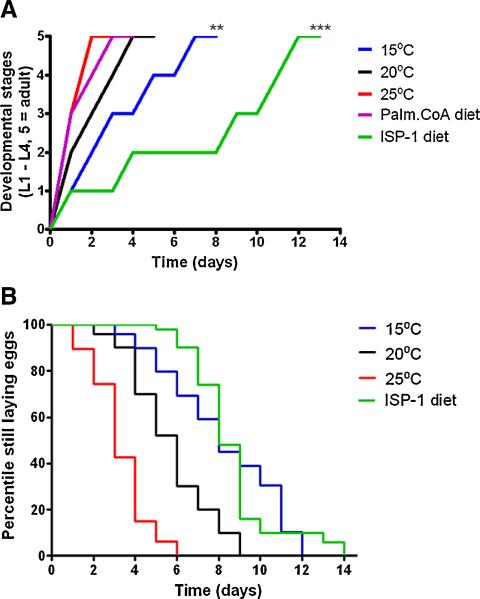

The relatively low level of sphingolipids in dauers suggests that the production and accumulation of sphingomyelins and/or gangliosides may regulate development and aging. To test this possibility, we reduced de novo sphingolipid synthesis using the SPT inhibitor ISP-1 (myriocin) (Miyake et al., 1995). ISP-1 was used in previous studies to demonstrate pivotal roles for sphingolipids in the proliferation, differentiation, and survival of cultured cells (Cutler et al., 2004; Hanada et al., 2000). We treated newly hatched worms with increasing concentrations of ISP-1 (10, 20, 25, and 30 μM) or vehicle control, then after 48 and 72 h, scored the number of worms that had reached specific developmental stages from L1 to adults (Fig. 4A and Table S2). In cultures of control worms, 91% of the worms were at stage L4 at 48 h post-hatching, and 98% were adults at the 72 h time point. ISP-1 treatment resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of development rate with a long pause at the L2 stage and slowed progression through the remaining stages. In particular, only 10% of the worms fed a diet containing 30 μM ISP-1 reached stage L4 at 72 h post treatment, with the majority remaining at developmental stage L2 (Fig. 4A and Table S2). While inhibition of sphingolipid synthesis halted development, increased availability through egg yolk or palmitoyl CoA diet supplementation, accelerated the developmental rate (Fig. 4A and Table S2). Furthermore, worms on the egg yolk diet were significantly less sensitive to the growth-inhibiting effect of ISP-1 (Table S2). Similarly to what was observed in long-lived worms maintained at 15 °C, the egg laying period was extended in worms fed food containing ISP-1 (Fig. 4B). To confirm that ISP-1 treatment did reduce sphingomyelin metabolism, we measured levels of long-chain ceramide (C24:0) in worms that had been treated with ISP-1 or vehicle from hatching until day 7 of adulthood and found that levels of the ceramide were reduced by approximately 75% (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Development rate is slowed in worms treated with an inhibitor of de novo sphingolipid synthesis.

(A) Plots show development rates of C. elegans maintained at the indicated temperatures, or treated with ISP-1 (at 20 ° C). **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 compared to untreated worms maintained at 20 ° C. B. The duration of the egg laying period, a measure of functional aging, is significantly increased in worms treated with ISP-1 at 20 ° C (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Worms were treated with the indicated pharmacological interventions (or vehicle) from the beginning at the time of hatching until day 7 of adulthood,at which time the worms were collected and processed for analysis of lipids.

| Intervention | Target | Result | % of control value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISP-1 | Serine palmitoyl-transferase | Decrease of ceramides | 24% ± 9617;11%** |

| C8CPC | Dihydroceramide desaturase | Decrease of ceramides | 27% ± 19%** |

| MAPP | Ceramidase | Increase of ceramides | 59% ± 14%* |

| PDMP | Glucosylceramide synthase | Decrease of glucosylceramide | 47% ± 13%* |

| D609 pro-drug | Sphingomyelin synthase | Decrease of sphingomyelin | 5% ± 2%*** |

| Epoxyquinone G109 | Neutral sphingomyelinase | Increase of sphingomyelin | 241% ± 37%** |

| C75 | Triglyceride synthase | Decrease of triglycerides | 1% ± 0.7%*** |

Values are the mean + SEM of measurements made in three separate batches of worms. ISP-1, myriocin; C8CPC, C8-cyclopreopenylceramide; MAPP, 1S, 2R-D-erythro-2-N-Myristoylamino-1-phenyl-1-propanol: d,l–erythro-phenyl-2-decanoylamino-3-morpholino-1-propanol hydrochloride; C75, 4-methylene-2-octyl-5-oxotetrahydrofuran-3-carboxylic acid.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

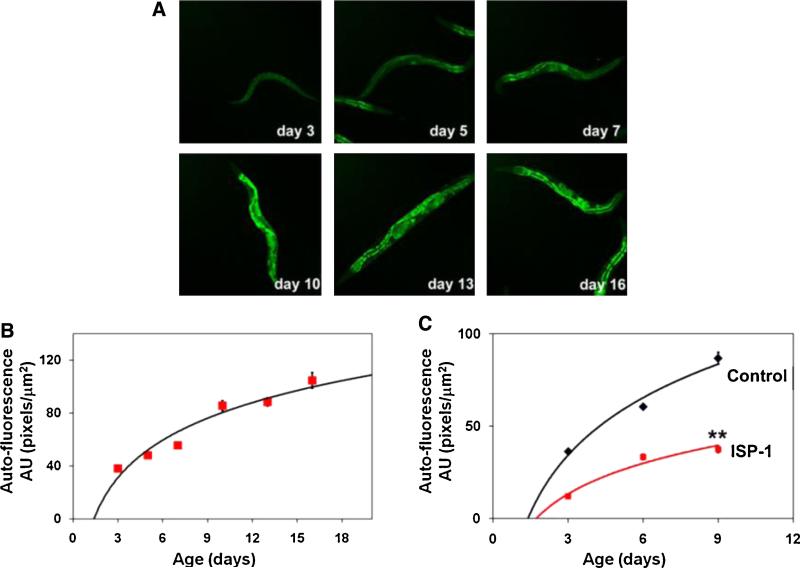

We next measured the accumulation of auto-fluorescence, which emanates primarily from oxidized lipids and proteins (lipofuscin-ceroid) formed in secondary lysosomes (Gerstbrein et al., 2005), as a biomarker of functional aging in control and ISP-1-treated worms. With advancing age of adult control worms, from 3 to 16 days, there was a progressive increase in auto-fluorescent materials in the worms (Fig. 5A and B). Worms fed food containing 30 μM ISP-1 exhibited a significant attenuation in the amount of auto-fluorescent materials that accumulated with advancing age (Fig. 5C, Fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

The accumulation of oxidatively damaged lipids is attenuated in worms treated with an inhibitor of de novo sphingolipid synthesis.

(A) Examples of auto-fluorescence in worms of the indicated ages. (B) Results of quantitative measurements of auto-fluorescence in worms of different ages. (C) The age-related accumulation of auto-fluorescent/oxidized lipids is attenuated in worms treated with the SPT inhibitor ISP-1. **p < 0.01 compared to worms not treated with ISP-1.

3.3. Chemical and genetic inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism slows development rate and extends lifespan

Because our lipidomic analyses revealed changes in multiple sphingolipids associated with development rate and aging, we determined the effects on development and lifespan of chemical inhibitors that target specific enzymes involved in ceramide, ganglioside, and sphingomyelin metabolism. The pharmacological inhibitors uses and their enzyme targets are detailed in Section 2.1 above and in Fig. 1A (for references on these inhibitors see Inokuchi et al., 1989; Uemura et al., 1991; Bielawska et al., 1996; Erdreich-Epstein et al., 2005; Li et al., 2007; Marza et al., 2009). The drug C75 (4-methylene-2-octyl-5-oxotetrahydrofuran-3-carboxylic acid) was used to inhibit triglyceride synthase (Wu et al., 2011) to determine if the availability of triglycerides affected development and/or lifespan in the worms. We validated the efficacy of each drug in inhibiting the target enzyme by treating worms with the inhibitor (or vehicle control) from hatching to adult day seven and then measuring levels of lipids downstream of the targeted enzyme. We found that compared to vehicle-treated control worms, levels of long-chain ceramide (C24:0) were reduced to 24% and 27% in worms treated with ISP-1 and C8CPC, respectively (Table 1). PDMP treatment reduced the level of glucosylceramide to less than 50% of the control level and treatment with D609 greatly reduced sphingomyelin levels to 5% of the control level (Table 1). As expected, treatment of worms with the sphingomyelinase inhibitor epoxyquinone G109 resulted in a significant increase in sphinomyelin levels. The triglyceride synthase inhibitor C75 was highly effective in reducing triglyceride levels to very low levels (Table 1). However, unexpectedly, the putative ceramidase inhibitor MAPP did not increase, but instead decreased, ceramide levels in the worms.

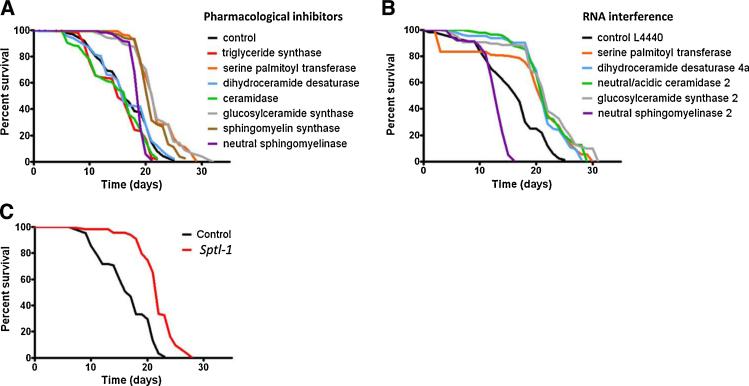

Inhibitors of SPT, sphingomyelin synthase, and glucosylceramide synthase (i.e., ganglioside synthesis) extended mean and maximum lifespan (Fig. 6A, Table 2). No effect was observed following inhibition of triglyceride synthesis (Table 2). Interestingly, inhibition of neutral sphingomyelinase, which causes an accumulation of sphingomyelin, increased mean lifespan, but had no significant effect on maximum lifespan as a majority of these worms died within a narrow 2 day time window (Fig. 6A). Each of the agents that extended lifespan (ISP-1, PDMP, and D609) acted to slow development rate (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Pharmacological and genetic inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism results in an extension of lifespan.

(A) Lifespan was determined in worms maintained in the presence of chemical inhibitors of the indicated enzymes (triacylglycerol synthase, C75; serine palmitoyl transferase, ISP-1; dihydroceramide desaturase, C8-CPC; ceramidase, MAPP; glucosylceramide synthase, PDMP; sphingomyelin synthase, D609; neutral sphingomyelinase, epoxyquinon G109). Lifespan was significantly extended in worms treated with inhibitors of serine palmitoyl transferase, glucosylceramide synthase, and sphingomyelin synthase (p < 0.01). (B) The effects of genetic siRNA targeting of enzymes involved in sphingolipid metabolism on lifespan was determined in worms in which the indicated enzymes were targeted with siRNAs. Lifespan was significantly extended in worms in which serine palmitoyl transferase, dihydroceramide desaturase, ceramidase or glucosylceramide synthase were targeted (p < 0.01). In contrast, lifespan was shortened when neutral sphingomeylinase was targeted (p < 0.01). (C) Serine palmitoyl transferase 1 (sptl-1) mutant worms exhibit a significant extension of lifespan (p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Effects of pharmacological and genetic manipulations of sphingolipid metabolism on development and lifespan.

| Intervention | Target | Developmental Delay |

Mean Lifespan |

Vs Control |

Maximum Lifespan |

Vs Control |

n | Effect on phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2: 15°C | slow metabolic rate | yes | 29 | 181% | 38 *** | 165% | 126 | adult size 14.9% larger |

| N2: 20°C | control | 16 | 100% | 23 | 100% | 110 | ||

| N2: 25°C | fast metabolic rate | no (accelerated) |

12 | 75% | 17 *** | 74% | 107 | adult size 13.3% smaller |

| N2: day 6 food removal | food signal and metabolic substrates | no | 33 | 206% | 41 *** | 178% | 96 | stopped adult hypertrophy |

| N2: Palm.CoA diet | serine palmitoyl transferase substrate | no (accelerated) |

15 | 94% | 20 * | 87% | 110 | adult size 25.5% larger |

| daf-2 (e1370) | insulin/IGF-1 like receptor | yes | 29 | 181% | 49 *** | 213% | 103 | adult size 38.6% smaller |

| N2: Dauer 50 day arrest/refeed |

14 | 21 | 91% | 101 | adult size 36.7% smaller | |||

| N2 | drug study control | 16 | 100% | 23 | 100% | 111 | ||

| C75 | triglyceride synthase | yes | 15 | 94% | 22 * | 96% | 122 | |

| ISP-1 | serine palmitoyl transferase | yes | 21 | 131% | 29 *** | 126% | 104 | adult size 20.2% smaller |

| C8 cyclopropenylceramide | dihydroceramide desaturase | yes | 17 | 106% | 25 * | 109% | 117 | |

| MAPP | ceramidase | no | 15 | 94% | 22 * | 96% | 123 | |

| PDMP | glucosylceramide synthase | yes | 22 | 138% | 32 *** | 139% | 107 | |

| D609 | sphingomyelin synthase | yes | 20 | 125% | 29 *** | 126% | 103 | |

| Epoxyquinone G109 | neutral sphingomyelinase | no | 17 | 106% | 21 * | 91% | 97 | |

| Control L4440 | non-specific dsRNA control | 15 | 100% | 25 | 100% | 120 | ||

| C23H3.4 | serine palmitoyl transferase homolog | yes | 20 | 133% | 30 *** | 120% | 113 | adult size 23.5% smaller |

| Y54E5A.1 | dihydroceramide desaturase delta 4a | yes | 21 | 140% | 28 * | 112% | 102 | |

| W02F12.2 | neutral alkaline ceramidase 2 | yes | 21 | 140% | 29 ** | 116% | 108 | |

| F20B4.6 | glucosylceramide synthase/ctg 2 | yes | 21 | 140% | 31 *** | 124% | 119 | adult size 17.1% smaller |

| K06A9.1 | neutral sphingomyelinase 2 | no (accelerated) |

12 | 80% | 14 *** | 56% | 116 | adult size 25.5% larger |

| N2 | knockout study control | 17 | 100% | 24 | 100% | 111 | ||

| RB1465 | serine palmitoyl transferase 1 | yes | 23 | 135% | 30 *** | 125% | 99 | adult size 27.3% smaller |

Table 2 Pharmacological, RNAi, and knockout interventions were designed to inhibit key regulatory targets of the sphingolipid pathway. Temperature, food withdrawal, high fat diet, and daf-2 mutation were used for comparison purposes. Data are expressed as relative change over the control group (i.e. N2: 20°C; N2 or L4440) set equal to 100% in each study.

p<0.05 versus control;

p<0.01 versus control;

p<0.001 versus control.

We additionally employed RNA interference (see Section 2) to target the mRNAs encoding the following C. elegans genes: C23H3.4 (SPT homologue); Y54E5A.1 (dihydroceramide desaturase homologue); W02F12.2 (neutral/acidic ceramidase homologue); F20B4.6 (glucosylceramide synthase homologue); and K06A9.1 (neutral sphingomyelinase homologue). The small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were incorporated into L4440 vectors transformed into HT115 (DE3) Rnase III-deficient bacteria fed to the worms (Fire et al., 1998). A non-specific double stranded RNA was used as a control. The development rates of worms expressing the dsR-NAs that target mRNAs encoding SPT, dihydroceramide desaturase, neutral/acidic ceramidase, and glucosylceramide synthase were significantly reduced compared to worms fed the control RNA (Table 2). Posttranscriptional silencing of each of the latter 4 genes also resulted in significant extension of both mean and maximum lifespan (Fig. 6B). In contrast, silencing of the gene encoding the worm neutral sphingomyelinase accelerated development rate and shortened lifespan (Fig. 6B, Table 2). We also found that the lifespan of SPT-deficient worms (sptl-1) was significantly longer than the lifespan of wild type worms (Fig. 6C), providing additional evidence that worm lifespan is limited by sphingolipid synthesis and metabolism.

4. Discussion

Our findings reveal previously unknown roles for sphingolipid synthesis and remodeling in the regulation of development and aging. Lipidomic measurements of ceramides, gangliosides, and sphingomyelin in C. elegans eggs, dauers, and adults of different ages revealed several prominent changes with development and aging. Previous studies have documented an age-related accumulation of one or more of these same lipids in tissues from other organisms including mammals. For example, during normal aging of mice there is a progressive increase in the amounts of sphingomyelin C24:0 and ceramide C24:0 in the brain (Cutler et al., 2004). Levels of long-chain ceramides are also elevated in the liver of old compared to young mice (Lightle et al., 2000). A study of white matter from human subjects of different ages revealed an increase in levels of C20:0 and C24:0 sphingomyelin with advancing age (Stommel et al., 1989). These same species of long-chain sphingomyelins and ceramides also accumulate in abnormally large amounts in humans in tissues affected by several age-related diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (Cutler et al., 2004), diabetes (Straczkowski and Kowalska, 2008) and cardiovascular disease (Bismuth et al., 2008). However, whether such alterations are actively involved in the aging and associated disease processes is still unknown.

We found that when the production of sphingolipids was inhibited both the mean and maximum lifespan of worms were significantly lengthened. In particular, the inhibition of the key upstream enzyme SPT slowed developmental rate, while increasing the duration of the egg laying period and lifespan. Previous studies of many different species have shown that environmental and genetic manipulations that extend lifespan also slow development rate and reduce fecundity (Kirkwood and Rose, 1991). In C. elegans, caloric restriction, reduced temperature and mutations in the insulin signaling pathway all extend lifespan and reduce fecundity (Kimura et al., 1997; Henderson and Johnson, 2001; Tatar et al., 2003). We found that ISP-1 slowed the development rate of C. elegans in a dose-dependent manner; whereas, dietary supplementation with the sphingolipid precursor palmitoyl CoA accelerated development rate, suggesting that sphingolipid production facilitates the process of development. Moreover, when the worms were fed egg yolk that is naturally high in gangliosides and sphingomyelins, the ability of ISP-1 to inhibit development was attenuated. The latter finding is consistent with studies of rodents and human populations, which indicate that diets high in fat and calories tend to accelerate development, including the onset of sexual maturity (Euling et al., 2008).

Levels of gangliosides GM1 and GM3 were significantly elevated with advancing age in the worms, and were present in very low amounts in developmentally arrested dauers. When worms were treated with a chemical inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase (PDMP), an enzyme necessary for ganglioside production from ceramide, or when this enzyme was targeted by RNA interference, there was a developmental delay and the worms lived longer. These findings provide evidence that gangliosides may be a particularly important regulator of development rate and lifespan. There is also evidence for the involvement of gangliosides in the pathogenesis of several age-related diseases. For example, GM1 can accelerate the development of amyloid pathology in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease (Hayashi et al., 2004), and GM3 plays a role in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in blood vessels (Bobryshev et al., 2006).

We found that C. elegans lifespan was significantly extended by both pharmacological inhibition and RNAi-mediated knockdown of SPT and glucosylceramide synthase. However, RNAi-mediated knockdown of dihydroceramide desaturase and neutral/acidic ceramidase extended lifespan, pharmacological agents known to inhibit these enzymes did not extend lifespan. One possible explanation for the latter results is that the pharmacological agents (C8-CPC and MAPP) may have off-target actions that adversely affect the health and longevity of the worms. Interestingly, we also found that whereas a pharmacological inhibitor neutral sphingomyelinase (G109) increased the average lifespan of the worms, RNAi-mediated knockdown of this enzyme shortened lifespan. Further studies will be required to clarify the mechanism whereby chronic suppression of neutral sphingomyelinase may adversely affect longevity.

We found that the accumulation of oxidatively damaged (auto-fluorescent) molecules during aging was significantly attenuated in worms treated with the SPT inhibitor ISP-1, suggesting that sphingomyelin, ceramide and/or gangliosides enhance oxidative stress. Previous studies have shown that levels of ceramide and sphingomyelins are significantly remodeled in association with oxidative damage to cells in age-related diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease (Cutler et al., 2004) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Cutler et al., 2002). In addition, exposure of cells to ceramides can cause oxidative damage (Schenck et al., 2007). Ceramide accumulation has also been shown to perturb insulin signaling, and is implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes (Holland et al., 2011). Insulin signaling is also affected by gangliosides (Lopez and Schnaar, 2009). Our discovery of critical role for sphingolipid metabolism as a determinant of development rate and lifespan, reveals a novel membrane lipid-based system involved in the regulation of cellular events that may couple the processes of development and aging. It will be of considerable interest to determine if and how insulin signaling and sphingolipid metabolism interact in the processes of development and aging.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The National Institute on Aging Intramural Research Program supported this research. We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (T. Stiernagle, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) (which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources (NCRR)) and the C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium (R. Barstead, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, OK) for providing the nematode and E. coli strains. We would also like to thank Wendy Iser for culturing and genotyping the RNAi strains used in this work, Mark Wilson for help with editing, and Cathy Wolkow for valuable advice and technical assistance.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2014.11.002.

References

- Bielawska A, Greenberg MS, Perry D, Jayadev S, Shayman JA, McKay C, Hannun YA. (1S, 2R)-D-erythro-2-(N-myristoylamino)-1-phenyl-1-propanol as an inhibitor of ceramidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:12646–12654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth J, Lin P, Yao Q, Chen C. Ceramide a common pathway for atherosclerosis? Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobryshev YV, Golovanova NK, Tra D, Samovilova NN, Gracheva EV, Efremov EE, Sobolev AY, Yurchenko YV, Lor RS, Cao W, Lu J, Saito M, Prokazova NV. Expression of GM3 synthase in human atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler RG, Pedersen WA, Camandola S, Rothstein JD, Mattson MP. Evidence that accumulation of ceramides and cholesterol esters mediates oxidative stress-induced death of motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2002;52:448–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler RG, Haughey NJ, Tammara A, McArthur JC, Nath A, Reid R, Vargas DL, Pardo CA, Mattson MP. Dysregulation of sphingolipid and sterol metabolism by ApoE4 in HIV dementia. Neurology. 2004;63:626–630. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134662.19883.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdreich-Epstein A, Tran LB, Cox OT, Huang EY, Laug WE, Shimada H, Millard M. Endothelial apoptosis induced by inhibition of integrins alphaVbeta3 and alphaVbeta5 involves ceramide metabolic pathways. Blood. 2005;105:4353–4361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euling SY, Selevan SG, Pescovitz OH, Skakkebaek NE. Role of environmental factors in the timing of puberty. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S167–S171. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1813C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielenbach N, Antebi A. C. elegans dauer formation and the molecular basis of plasticity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2149–2165. doi: 10.1101/gad.1701508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gami MS, Wolkow CA. Studies of Caenorhabditis elegans DAF-2/insulin signaling reveal targets for pharmacological manipulation of lifespan. Aging Cell. 2006;5:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch B, Weitzel C, Kober-Eisermann C, Rottiers V, Antebi A. A hormonal signaling pathway influencing C. elegans metabolism, reproductive development, and life span. Dev. Cell. 2001;1:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstbrein B, Stamatas G, Kollias N, Driscoll M. In vivo spectrofluorimetry reveals endogenous biomarkers that report healthspan and dietary restriction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2005;4:127–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbins E, Kolesnick R. Raft ceramide in molecular medicine. Oncogene. 2003;22:7070–7077. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K, Nishijima M, Fujita T, Kobayashi S. Specificity of inhibitors of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), a key enzyme in sphingolipid biosynthesis, in intact cells. A novel evaluation system using an SPT-defective mammalian cell mutant. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:1211–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–150. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Kimura N, Yamaguchi H, Hasegawa K, Yokoseki T, Shibata M, Yamamoto N, Michikawa M, Yoshikawa Y, Terao K, Matsuzaki K, Lemere CA, Selkoe DJ, Naiki H, Yanagisawa K. A seed for Alzheimer amyloid in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4894–4902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0861-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland WL, Bikman BT, Wang LP, Yuguang G, Sargent KM, Bulchand S, Knotts TA, Shui G, Clegg DJ, Wenk MR, Pagliassotti MJ, Scherer PE, Summers SA. Lipid-induced insulin resistance mediated by the proinflammatory receptor TLR4 requires saturated fatty acid-induced ceramide biosynthesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:1858–1870. doi: 10.1172/JCI43378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsin H, Kenyon C. Signals from the reproductive system regulate the lifespan of C. elegans. Nature. 1999;399:362–366. doi: 10.1038/20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Liu J, Dickson RC. Down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis increases yeast lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(2):e1002493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi J, Momosaki K, Shimeno H, Nagamatsu A, Radin NS. Effects of D-threo-PDMP, an inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthetase, on expression of cell surface glycolipid antigen and binding to adhesive proteins by B16 melanoma cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1989;141:573–583. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041410316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, Mitchell DH, Kline S, Kemal R, Foy J. Arresting development arrests aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1984;28:23–40. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood TB, Rose MR. Evolution of senescence: late survival sacrificed for reproduction. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B Biol. Sci. 1991;332:15–24. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnick RN, Tilly JL. A central role for ceramide in the age-related acceleration of apoptosis in the female germline. FASEB J. 2005;19:860–862. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2903fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Hailemariam TK, Zhou H, Li Y, Duckworth DC, Peake DA, Zhang Y, Kuo MS, Cao G, Jiang XC. Inhibition of sphingomyelin synthase (SMS) affects intracellular sphingomyelin accumulation and plasma membrane lipid organization. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1771:1186–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightle SA, Oakley JI, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Activation of sphingolipid turnover and chronic generation of ceramide and sphingosine in liver during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2000;120:111–125. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Hengartner MO, Kolesnick R. Caenorhabditis elegans contains two distinct acid sphingomyelinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:14374–14379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Huang X, Withers BR, Blalock E, Liu K, Dickson RC. Reducing sphingolipid synthesis orchestrates global changes to extend yeast lifespan. Aging Cell. 2013;12:3–841. doi: 10.1111/acel.12107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochnit G, Bongaarts R, Geyer R. Searching new targets for anthelminthic strategies: interference with glycosphingolipid biosynthesis and phosphorylcholine metabolism affects development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005;35:911–9236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez PH, Schnaar RL. Gangliosides in cell recognition and membrane protein regulation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009;19:549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marza E, Simonsen KT, Færgeman NJ, Lesa GM. Expression of ceramide glucosyltransferases, which are essential for glycosphingolipid synthesis, is only required in a small subset of C. elegans cells. J. Cell Sci. 2009;122:122–833. doi: 10.1242/jcs.042754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattison JA, Lane MA, Roth GS, Ingram DK. Calorie restriction in rhesus monkeys. Exp. Gerontol. 2003;38:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill AH, Jr., Jones DD. An update of the enzymology and regulation of sphingomyelin metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990;1044:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90211-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake Y, Kozutsumi Y, Nakamura S, Fujita T, Kawasaki T. Serine palmitoyltransferase is the primary target of a sphingosine-like immunosuppressant, ISP-1/myriocin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;211:396–403. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooradian AD. Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;5:150–159. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay A, Tissenbaum HA. Reproduction and longevity: secrets revealed by C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricklefs RE. Embryo development and ageing in birds and mammals. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006;273:2077–2082. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck M, Carpinteiro A, Grassmé H, Lang F, Gulbins E. Ceramide physiological and pathophysiological aspects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;462:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stommel A, Berlet HH, Debuch H. Buoyant density and lipid composition of purified myelin of aging human brain. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1989;48:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(89)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straczkowski M, Kowalska I. The role of skeletal muscle sphingolipids in the development of insulin resistance. Rev. Diabet Stud. 2008;5:13–24. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2008.5.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatar M, Bartke A, Antebi A. The endocrine regulation of aging by insulin-like signals. Science. 2003;299:1346–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1081447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K, Sugiyama E, Taketomi T. Effects of an inhibitor of glucosylceramide synthase on glycosphingolipid synthesis and neurite outgrowth in murine neuroblastoma cell lines. J. Biochem. 1991;110:96–102. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venable ME, Webb-Froehlich LM, Sloan EF, Thomley JE. Shift in sphingolipid metabolism leads to an accumulation of ceramide in senescence. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2006;127:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts JL, Browse J. Dietary manipulation implicates lipid signaling in the regulation of germ cell maintenance in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 2006;292:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Singh SB, Wang J, Chung CC, Salituro G, Karanam BV, Lee SH, Powles M, Ellsworth KP, Lassman ME, Miller C, Myers RW, Tota MR, Zhang BB, Li C. Antidiabetic and antisteatotic effects of the selective fatty acid synthase (FAS) inhibitor platensimycin in mouse models of diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:5378–5383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002588108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yappert MC, Rujoi M, Borchman D, Vorobyov I, Estrada R. Glycero-versus sphingo-phospholipids: correlations with human and non-human mammalian lens growth. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;76:725–734. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.