Abstract

Background

Circulating endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are recruited from the blood system to sites of ischemia and endothelial damage, where they contribute to the repair and development of blood vessels. Since numerous eicosanoids including leukotrienes (LTs) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) have been shown to exert potent pro-inflammatory activities, we examined their levels in chronic diabetic patients with severe cardiac ischemia in conjunction with the level and function of EPCs.

Results

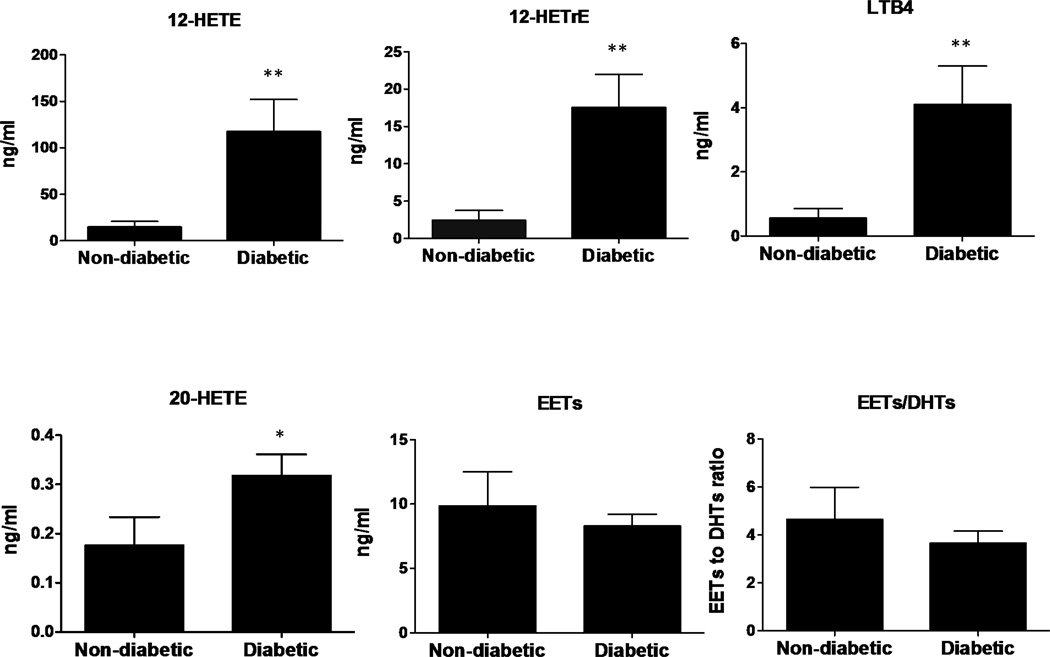

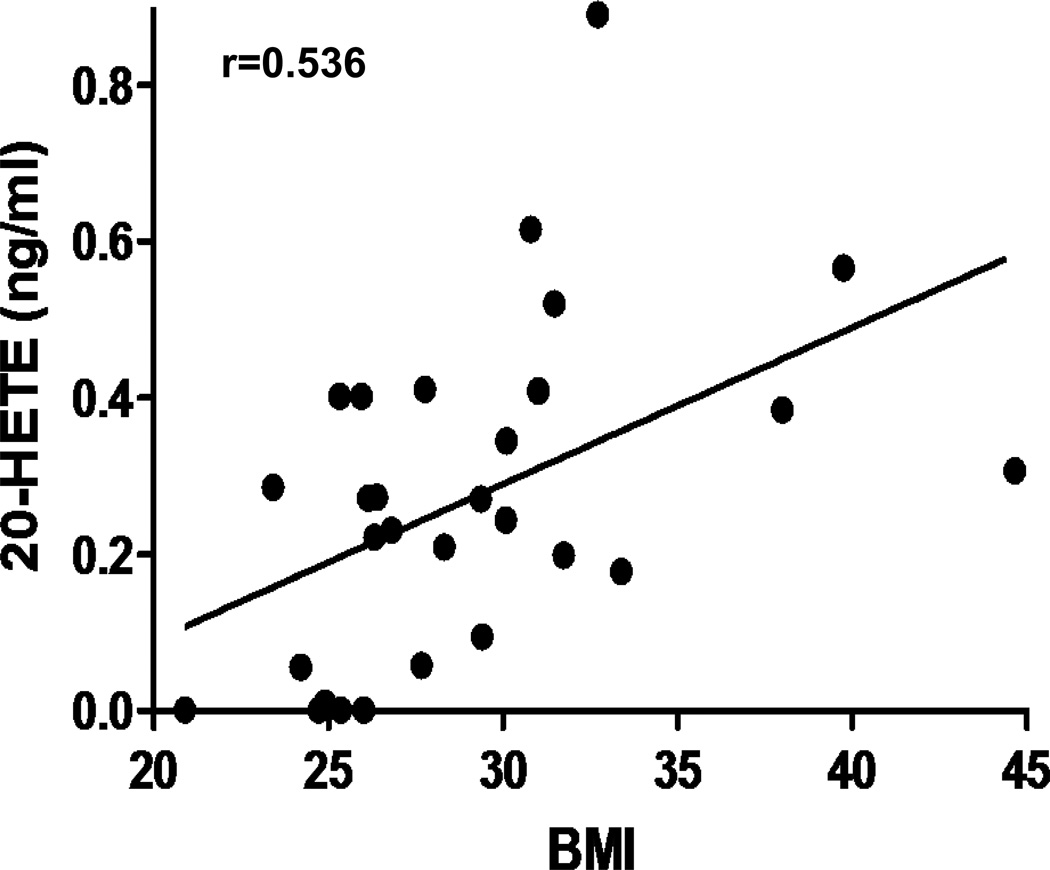

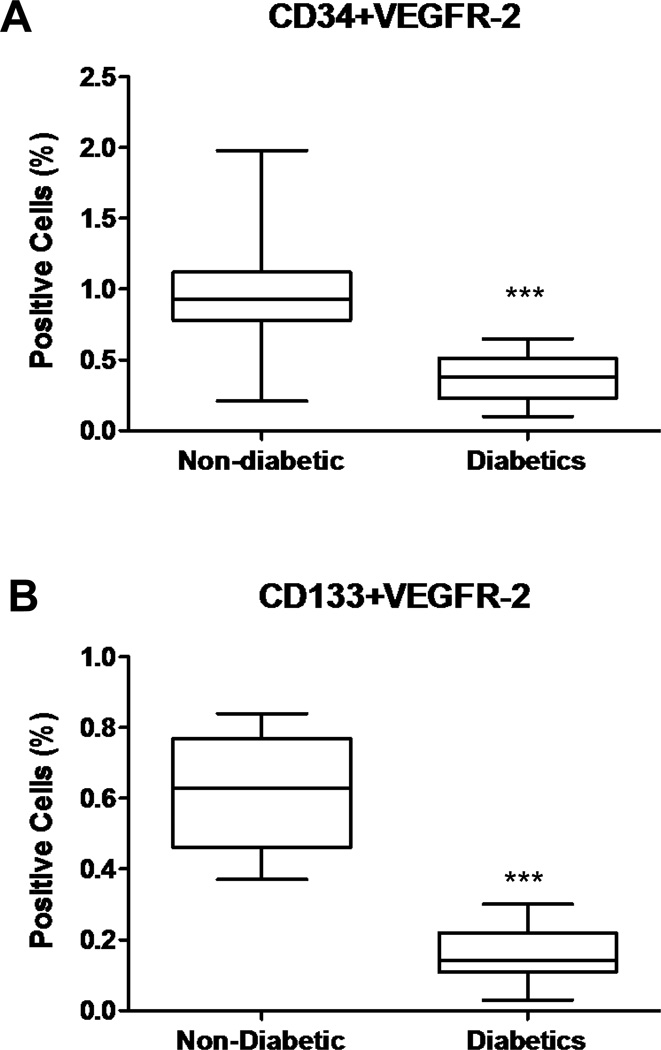

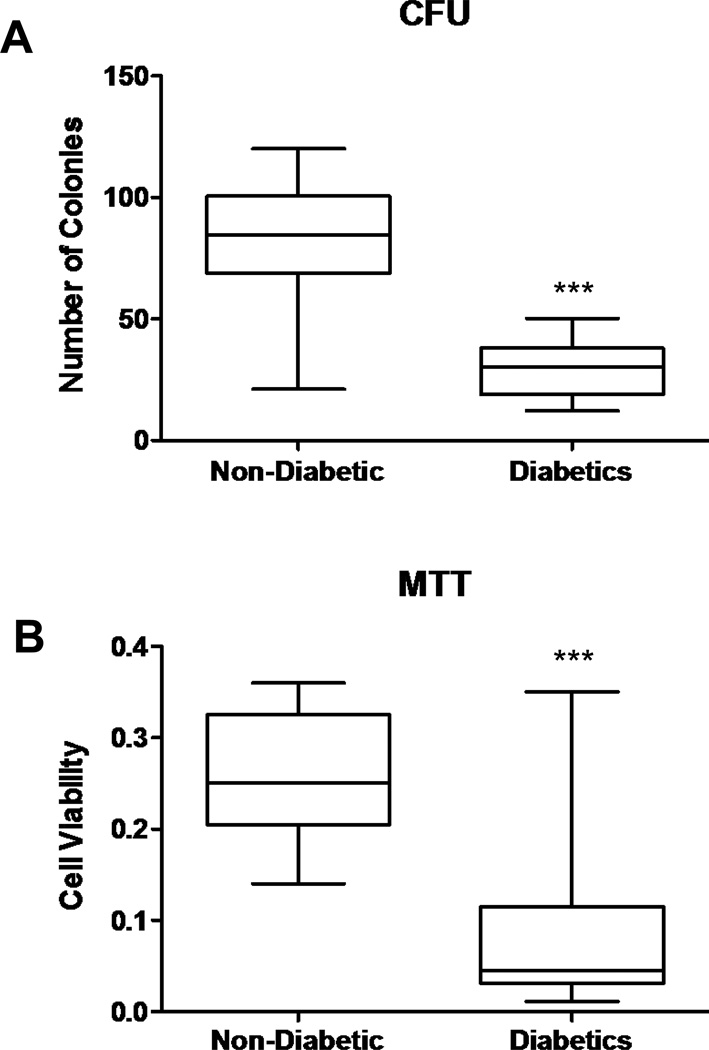

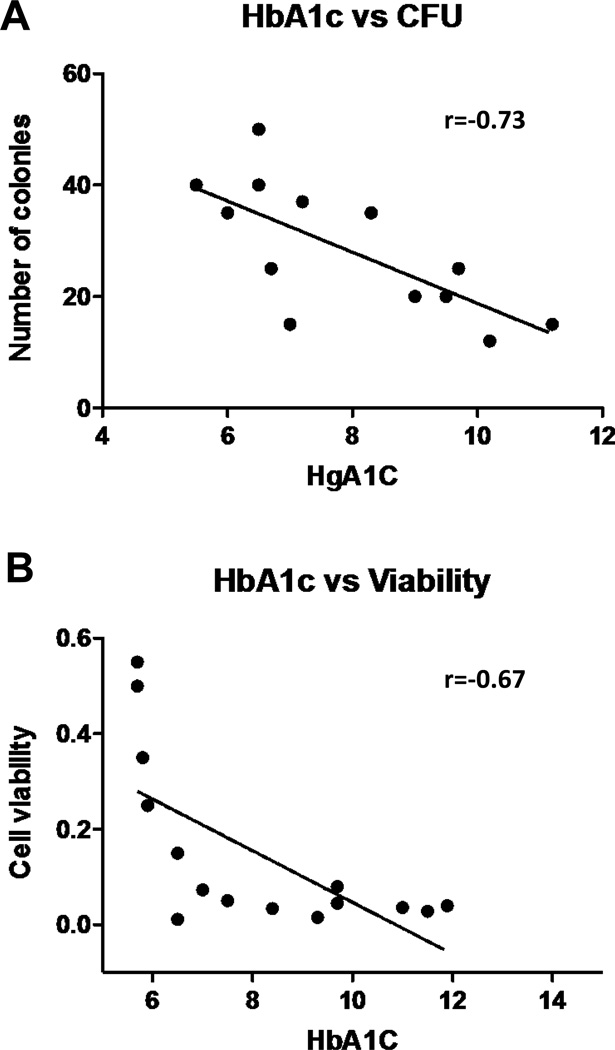

Lipidomic analysis revealed a diabetes-specific increase (p<0.05) in inflammatory and angiogenic eicosanoids including the 5-lipoxygenase-derived LTB4 (4.11±1.17 vs 0.96±0.27 ng/ml), the lipoxygenase/CYP-derived 12-HETE (117.08±35.05 vs 24.34±10.03 ng/ml), 12-HETrE (17.56±4.43 vs 4.15±2.07 ng/ml), and the CYP-derived 20-HETE (0.32±0.04 vs 0.06±0.05 ng/ml) the level of which correlated with BMI (p=0.0027). In contrast, levels of the CYP-derived EETs were not significantly (p= 0.36) different between these two groups. EPC levels and their colony forming units were lower (p<0.05) with a reduced viability in diabetic patients compared with non-diabetics. EPC function (Colony-Forming Units (CFUs) and MTT assay) also negatively correlated with the circulating levels of HgA1C.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a close association between elevated levels of highly pro-inflammatory eicosonoids, diabetes and EPC dysfunction in patients with cardiac ischemia, indicating that chronic inflammation impact negatively on EPC function and angiogenic capacity in diabetes.

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis is an essential process during development — growth of a vascular system is one of the earliest events in organogenesis. Nonetheless it also occurs in adulthood, during wound healing and restoration of blood flow to injured tissues. The mechanisms of angiogenesis, particularly with regard to collateral vessel (CV) development, are becoming an increasingly important area of cardiovascular physiology. In coronary artery disease (CAD) CV growth is a compensatory mechanism in response to ischemia1, 2. Diabetes is associated with an increased incidence of morbidity and mortality from atherosclerosis and the ensuing CAD may be due to an impaired ability to form CV in the diabetic patients2, 3.

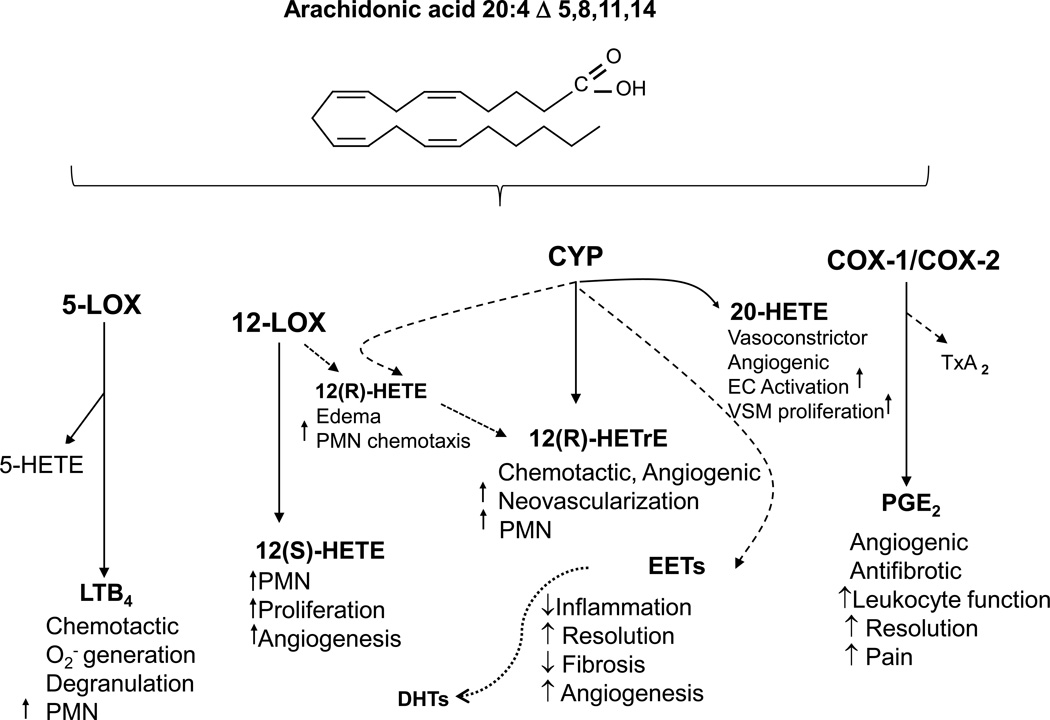

The angiogenic process is controlled by the net balance between molecules that have positive and negative regulatory activity. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been demonstrated to be a major contributor to angiogenesis, increasing the number of capillaries in a given network4. In addition to VEGF, numerous proteins, growth factors and small lipid molecules are involved in the angiogenic process. Among small lipid autacoids that participate in the regulation of angiogenesis are the arachidonic acid derived metabolites, termed eicosanoids. These metabolites are formed by cyclooxygenases (COX), lipoxygenases (LOX) and cytochrome P450 monoooxygenases (CYP) and include prostanoids (PGs), leukotrienes (LTs), hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs)5. These eicosanoids display potent inflammatory and angiogenic properties and have shown to modulate inflammation and angiogenesis6–9 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Role of Eicosanoids in the Regulation of Inflammation

Endothelial cell (EC) migration and proliferation are critical events in angiogenesis. Emerging evidence suggests that eicosanoids play a role in the regulation of cell migration, proliferation, and apoptosis10. Diabetes is associated with reduced vascular repair, as indicated by impaired wound healing and reduced collateral formation in ischemia. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are bone marrow cells that have the capacity to migrate to the peripheral circulation and to differentiate into mature endothelial cells. Early functional EPCs are characterized by expression of three markers, CD133, CD34, and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) also termed kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) or Flk-111, 12. EPCs play a significant role in the re-endothelialization and neovascularization of injured endothelium13. However, cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes have been shown to reduce the number and impair the function of circulating EPCs, thereby impairing endothelial repair capacity14. Diabetes impairs EPCs migration, differentiation to a mature endothelial phenotype, adhesive properties13 and the capacity to proliferate and to incorporate into vascular structures15. In addition, inflammation further abrogates the repair capacity and number of EPC. Several studies have demonstrated that an incubation of EPC with pro-inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein 16 and TNFα 17 reduced EPC survival and number.

This study aimed at examining the levels of inflammatory and angiogenic eicosanoids in serum from diabetic and non-diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery in conjunction with the level and function of EPCs. We report here that levels of inflammatory eicosanoids with potent angiogenic activity such as LTB4 and 12-HETrE are significantly elevated in serum from diabetic patients with CAD as compared to their counterpart non-diabetic patients. These elevated levels corresponded with decreased EPC levels and function in the diabetic patients. EPC function negatively correlates with the circulating levels of HbA1c (an index of long-term glucose control). It seems that chronic hyperglycemia and inflammation impacts on EPC function and compromises the angiogenic activity of these eicosanoids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

The experimental group comprised 20 diabetic (type 2) and 15 non-diabetic patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). In both groups only patients currently treated with statins were included. Contraindications to inclusion in both groups were anaemia (haemoglobin <10 g/dL), renal insufficiency (creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dL), insulin treatment, history of an ACS or revascularization in the past three months, any type of malignancy, or haematologic disorder. The diabetic groups were diagnosed with diabetic type 2 at least 5 years prior to the study and were treated with the following medications: Metformin or Glibenclamide. The study was approved by the Investigational Review Board (Ethics Committee) of the Rabin Medical Center, Israel and all subjects signed a written informed consent.

Blood samples

One day before surgery, following overnight fasting, venous blood was drawn from an antecubital vein for plasma levels of eicosanoids and EPC testing (blood drawn in heparinized tubes). Blood samples for HbA1c, cholesterol, HDL, LDL and triglycerides were processed within 1 h of blood collection, according to the manufacturer's protocol. All biochemical parameters were measured by the hospital central biochemistry laboratory using the Beckman Coulter AU2700Plus® Chemistry System.

LC-MS/MS-based lipidomics

For measurements of eicosanoids in plasma, acidified water (pH 4) and 1 ng of internal standard mix were added to thawed plasma (400 µl) and first extracted with 5 vol chloroform/methanol (2:1) followed by addition of 2×1 vol chloroform. The chloroform layers were combined and dried under nitrogen. Alkali hydrolysis was performed by adding 1 ml 1M NaOH to each sample followed by 90 min incubation at room temperature. Samples were neutralized with 1M HCL and loaded onto preconditioned Strata-X-SPE columns (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA), washed with 2 ml 10% methanol, and eluted with 2 ml of 100% methanol. All samples were dried under nitrogen and stored at −80°C until LC/MS/MS analysis. Identification and quantification of eicosanoids were performed with a Q-trap 3200 linear ion trap quadrupole LC/MS/MS equipped with a Turbo V ion source operated in negative electrospray mode (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Multiple reaction monitoring was used with a dwell time of 25 or 50 ms for each compound, with source parameters: ion spray voltage, −4500 V; curtain gas, 40 U; ion source gas flow rate 1, 65 U and 2, 50 U; and temperature of 600°C. Synthetic - standards (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) were used to obtain standard curves (5–500 pg) for each eicosanoid and internal standard. The amounts in each sample were calculated from the standard curves and corrected for extraction efficiency.

Circulating EPC levels and viability

Circulating EPC levels were quantified by measuring the EPC surface markers VEGFR-2, CD34, and CD133 using flow cytometry. Functional aspects of EPCs were evaluated by measurement of colony-forming units (CFUs) and by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assays of cultured cells after 7 days of culture. To evaluate the viability of cultured EPCs in randomly selected patients in each group, we performed the MTT assay which measures mitochondrial activity in living cells. After 7 days of culture, 1 mg/mL MTT (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) was added to the EPC medium culture and incubated for an additional 3–4 h. The medium was removed and the cells were solubilized in isopropanol as previously described17.

Isolation of mononuclear cells and EPC colony formation

Peripheral mononuclear cells (PMNCs) were fractionated using Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation. Isolated PMNCs were re-suspended with Medium 199 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL Life Tech, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Isolated cells were re-suspended in Medium 199 and plated on 6-well plates coated with human fibronectin at a concentration of 5×106 cells per well. After 48 h, the non-adherent cells were collected and re-plated onto fibronectin-coated 24-well plates (106 cells/well). Endothelial progenitor cell colonies were counted using an inverted microscope 7 days after plating. An EPC colony was defined as a cluster of at least 100 flat cells surrounding a cluster of rounded cells, as previously described18. A central cluster alone without associated emerging cells was not counted as a colony. To confirm endothelial cell lineage, indirect immunostaining of randomly selected colonies was performed with antibodies directed against VEGFR-2, CD31 (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) and Tie-2 (Santa Cruz, Biotechnology, CA, USA) as previously demonstrated19.

Flow cytometry

Aliquots of PMNCs were incubated with monoclonal antibodies against VEGFR-2 (FITC labelled) (R&D, Minneapolis, USA) CD45-CYT5.5 (Dako, Denmark) and either CD133 (PE-labelled) (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA, USA) or CD34 (PE-labeled) (Miltenyi). BiotechIsotype-identical antibodies were used as controls. After incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and analyzed with a flow cytometer (FACS Calibur, Becton Dickinson, Chicago USA). CD34 or CD133-positive cells were examined for VEGFR-2 expression. Analyses were performed in duplicate. Results are presented as the percentage of PMNCs (after selection for CD45+ and exclusion of debris) co-expressing either VEGFR-2 and CD133, or VEGFR-2 and CD34.

Statistical analysis

EPC parameters were non-normally distributed (as determined by Shapiro–Wilk normality test). Therefore, EPC data are presented as median (twenty-fifth to seventy-fifth percentiles). EPC parameter comparison between the two groups was performed by Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank, two-tailed test. The MTT comparisons were performed in subgroups and were compared by Wilcoxon non-matched test. Other parameters in the study were analyzed using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test and are presented as mean±SEM. The relationship between two parameters was analyzed using the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. The analyses were performed using SPSS version 15 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Clinical characteristics including prior MI (no prior MI in 65 and 60% of diabetic and non-diabetic patients, respectively), PVD (25 and 20% of diabetic and non-diabetic patients, respectively) and current medications (β-blockers, calcium blockers and aspirin) were not different between the two experimental groups (diabetic and non-diabetic patients) with the exception of HbA1c (p<0.002) and blood sugar (p<0.001) that were significantly higher in diabetic patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Diabetes (n =20) |

Non diabetes (n =15) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 56.5±10.4 | 64.1±10.5 | Age (years) |

| 3(15) | 3(20) | Female, n (%) |

| 28.7±5.1 | 28.9±5.48 | Body mass index (kg/m2) |

| 15(75) | 13(87) | Hypertension, n (%) |

| 4(20) | 6(40) | Current smoker, n (%) |

| 0.62±0.17 | 0.47±0.15 | CRP (mg/dl) |

| 176±17# | 94±13 | Blood glucose (mg/dl) |

| 8.01±1.5* | 5.81±0.164 | HgA1C (%) |

| 183.2±65 | 146±36 | Triglycerides (mg/dl) |

| 164.9±31 | 160±28 | Total cholesterol (mg/dl |

| 43±7 | 42±11 | HDL (mg/dl) |

| 83.7±20.7 | 102±26 | LDL (mg/dl) |

p=0.001;

p=0.002

Effect of diabetes on serum levels of eicosanoids

Plasma from diabetic patients displayed 4–5-fold higher levels of the 12-lipoxygenase/CYP-derived metabolites 12-HETE and 12-HETrE when compared to non-diabetic patients (Figure 2A–B). The 5-lipoxygenase-derived LTB4 was also 4-fold higher in diabetic patients (Figure 2C) as were the levels of 5-HETE (172±46 vs 34±16 in diabetic vs non-diabetics, p=0.027). The levels of 20-HETE, a CYP4A-derived eicosanoids formed by the vascular wall as well as by EPC and hematopoietic cells20, 21, was also higher in diabetic patients (Figure 2D). The levels of the CYP-derived EETs, which have been shown to act as anti-inflammatory and angiogenic factors, were similar in samples from diabetics and non-diabetics patients (Figure 2E). Similarly, the levels of the EETs hydrolytic metabolites, DHTs, were unchanged (data not shown) and so was the ratio of EETs to DHTs, which is an index of epoxide hydrolase activity (Figure 2F). Noteworthy is the observation of undetectable amounts of prostanoids including PGE2 and TxB2 in all samples (data not shown). Interestingly, 20-HETE was the only eicosanoid measured in this study whose levels were significantly correlated with BMI (Figure 3). The differences in eicosanoid levels between diabetic and non-diabetic patients were independent of age, sex, BMI and smoking status.

Figure 2.

Serum levels of 12-HETE, 12-HETrE, LTB4, 20-HETE, EETs and DHTs in diabetic and non-diabetic cardiac ischemic patients (Mann-Whitney test, Mean±SE; *p<0.05; **p<0.01 vs Non-diabetic).

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis between serum levels of 20-HETE and BMI of cardiac ischemic patients (n=35; r=0.536, p=0.0027).

Effect of diabetes on circulating levels of endothelial progenitor cells

We examined the endothelial cell lineage, by indirect immunostaining of randomly selected colonies with antibodies directed against VEGFR-2, CD31, and Tie-2 confirming the endothelial cell lineage (data not shown). The numbers of circulating EPCs, as determined by co-expression of two EPC markers, CD34 and VEGFR-2 or CD133 and VEGFR-2, and quantified using flow cytometry, are shown in Figure 4. The number of circulating EPCs was significantly lower in diabetic patients compared to the non-diabetic patients (p <0.0001, Figure 4A, B).

Figure 4.

Effect of diabetes on the proportion of cells that co-expressed (A) VEGFR-2 and CD34, or (B) VEGFR-2 and CD133 in cardiac ischemic patients (n=15 in each group, ***p <0.0001).

Effect of diabetes on EPC colony formation and viability

The number of EPC-CFUs following 7 days of culture was also lower among the diabetic patients compared with the controls (p<0.0001, Figure 5A). The effects of hyperglycemia on the viability of the cells were determined by MTT assay. The viability of the cells was lower among diabetics compared with the control group (p<0.0001 Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

A) Effect of diabetes on the ability to form colonies (CFU) in cardiac ischemic patients (n=14 in each group, ***p <0.0001). B) Effect of diabetes on EPC viability measured by the MTT assay (n=15 in each group, ***p<0.0001).

Associations of EPC levels, EPC-CFU formation and viability with HbA1c

We did not find statistically significant correlations between the number of EPCs and the levels of HbA1c in the diabetic patients. In contrast, negative correlations between EPC-CFUs and HbA1c (r=−0.73, p=0.0029, Figure 6A) and also between viability of the colonies and HbA1c (r=−0.67, p=0.0059, Figure 6B) were observed. It seems that The EPC function as measured by their ability to form viable EPC-CFU colonies, but not number, is affected by hyperglycemia (HbA1c levels).

Figure 6.

Correlation analyses between (A) number of CFU and HbA1c levels, and (B) cell viability (measured by the MTT assay) and HbA1c levels (CFU, r=−0.73, p=0.0029, n=14; cell viability, r=−0.67, p=0.0059, n=15).

DISCUSSION

The results obtained in this study demonstrates elevated levels of key inflammatory and angiogenic eicosanoids in plasma from diabetic patients with chronic myocardial ischemia undergoing bypass surgery as compared to non-diabetic patients with the same conditions. In the same patient population, diabetes was associated with reduced levels and function of EPCs in these patients.

Ischemic heart disease is the most common cause of mortality in diabetic patients. Diabetic patients exhibit accelerated atherosclerosis and a diminished angiogenic response to myocardial ischemia, as shown by angiograph22 and by autopsy3. Angiogenesis is subject to a complex control system governed by the actions of pro- and anti-angiogenic factors. In adults, angiogenesis is tightly controlled by an “angiogenic balance”, i.e., a balance between the stimulatory and inhibitory signals for blood vessel growth. A significant number of pro-angiogenic cytokines involved in this process have been identified, including the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family, the platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) family23 and eicosanoids24, 25.

Numerous LOX and CYP-derived eicosanoids have been identified as potent inflammatory mediators with angiogenic activities26–29 and their presence in blood has been suggested to serve as indices of inflammation. The cellular sources of these eicosanoids in blood are numerous and include the vascular endothelium and circulating blood cells such as polymorphonuclear cells, monocytes, macrophages, platelets and EPCs30–35. The 12-LOX product, 12-HETE, has been reported to enhance both angiogenesis and tumor growth. 12-HETE has been shown to contribute to tumor angiogenesis via a VEGF-dependent pathway36, to stimulate endothelial cell division37 and tube formation38 and increases the surface expression of αvβ3, an integrin which is predominantly associated with angiogenic blood vessels in tumors and human wound granulation tissue39 in both rat aorta endothelial cells40, 41. Studies by Nadler and colleagues have demonstrated increased urinary excretion of 12-HETE in diabetic patients and documented its angiogenic and inflammatory properties in different cellular and animal models of diabetes42, 43. Others have shown increased serum levels of 12-HETE in diabetic patients and suggested that 12-HETE can serve as a biomarker for diabetes44, 45. LTB4, a prominent 5-lipoxygenase-derived eicosanoid is known for its potent inflammatory properties exemplified by its strong neutrophil chemotactic activity. Its effect on endothelial cell function and angiogenesis has been documented in several studies. LTB4 has been shown to induce endothelial cell migration and tube formation in vitro and stimulate VEGF-induced angiogenesis through the BLT2 receptor in vivo27. In addition, LTB4 enhances hypoxia-induced microvascular alterations in vivo46. With regard to EPC function, LTB4 was found to trigger a significant increase in adhesion of CD34+/CD133+/VEGFR2+ EPCs in culture47, suggesting that it may promote the angiogenic process. To this end, a study by Finkensieper et al48 demonstrated that inhibition of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway exert anti-angiogenic effect in differentiating embryonic stem cells. In our study, diabetes was associated with a marked increase in 5-lipoxygenase activity as both 5-HETE and LTB4 displayed 4–5 higher levels in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetics. Interestingly, recent studies suggested that 5-lipoxygenase pathway plays a role in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy and suggested that its products (e.g., 5-HETE and LTB4) are biomarkers of diabetic vascular complications49, 50.

Among the CYP-derived eicosanoids, EETs, 20-HETE and 12-HETrE have been shown to affect endothelial cell function and promote an angiogenic phenotype in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo9, 21, 51–54. While both 20-HETE and 12-HETrE, a LOX or CYP-derived eicosanoid, are potent pro-inflammatory mediators exerting effects such as neutrophil chemoattraction and increased inflammatory cytokines and chemokine production51–53, EETs have been identified as potent anti-inflammatory mediators9. The fact that EETs levels were not elevated in diabetic patients suggests that the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory eicosanoids is slanted towards those with potent inflammatory actions. The presence of a highly inflamed milieu in spite of ample angiogenic drive in diabetic patients may be, at least in part, the underlying cause of impaired EPC function.

Of note is the significant correlation between levels of 20-HETE in the plasma and BMI regardless of their diabetic state. This finding is in agreement with a study by Ward et al55 that demonstrated a significant positive association between 20-HETE and BMI in untreated hypertensive and normotensive individuals independent of either serum insulin or insulin resistance. In animal studies, Yousif et al56 showed that cardiac 20-HETE’s biosynthesis is higher in diabetic rats and inhibition of 20-HETE reduces cardiac dysfunction following ischemic events in diabetes. Theken et al57 showed high levels of 20-HETE in mice fed high fat diet. The same group studied levels of CYP-derived eicosanoids including 20-HETE in patients with CAD and showed no association between 20-HETE levels, CAD and obesity while levels of EETs were negatively correlated with obesity58. Our finding suggests a link between 20-HETE and obesity that may be used as a biomarker for cardiovascular complications associated with obesity.

Several clinical conditions characterized by both increased inflammation and oxidative stress, such as diabetes mellitus are associated with a reduced number and impaired functionality of EPCs59. Hyperglycemia can increase ROS production in many cell lines, including EPCs60. Compared with controls, our diabetic patients had significantly lower circulating cells co-expressing VEGFR-2, CD133, and CD34. The EPC's functional assays (CFU and viability of the colonies) demonstrated a reduction in their function in diabetic patients. The ability to form colonies and the viability of the cells correlates inversely with HgA1C levels.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates increased levels of several eicosanoids with potent inflammatory properties, reduced levels of circulating EPCs and impaired functional properties of EPC in diabetic as compared to non-diabetics patients with ischemic heart conditions. The association between plasma levels of eicosanoids and EPC function in the diabetic patients is unclear and needs to be further investigated using a larger cohort of patients. However, we can reason that despite the presence of abundant angiogenic drive exemplified by eicosanoids such as 12-HETE, 12-HETrE and 20-HETE in diabetic patients, inflammation that is also part of the bioactions of these eicosanoids may be a contributing factor to impaired EPC function. Non-functional EPCs may reduce the vascular regenerative potential of these patients and could further contribute towards diabetes-associated vascular complications.

Highlights.

The study identifies diabetic-specific increases in several known inflammatory eicosanoids in patients with CAD undergoing bypass surgery.

The study demonstrates a significant correlation between BMI and serum levels of 20-HETE independent of diabetes.

The study shows a significant diabetic-specific reduction in the number and function of circulating endothelial progenitor cells.

The presence of a highly inflamed milieu in spite of ample angiogenic drive in diabetic patients may be the underlying cause of impaired EPC function.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by National Institute of Health grant HL343000. This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree of Yossi Issan, Sackler Faculty of medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waltenberger J. Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49(3):554–560. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivard A, Silver M, Chen D, et al. Rescue of diabetes-related impairment of angiogenesis by intramuscular gene therapy with adeno-VEGF. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(2):355–363. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yarom R, Zirkin H, Stammler G, Rose AG. Human coronary microvessels in diabetes and ischaemia. Morphometric study of autopsy material. J Pathol. 1992;166(3):265–270. doi: 10.1002/path.1711660308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto F, Goto K, Weindel K, Folkman J. Synergistic effects of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor on the proliferation and cord formation of bovine capillary endothelial cells within collagen gels. Lab Invest. 1993;69(5):508–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 10(3):181–193. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nie D, Honn KV. Cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase and tumor angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59(5):799–807. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8468-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanapure SP, Garvey DS, Janero DR, Letts LG. Eicosanoids in inflammation: biosynthesis, pharmacology, and therapeutic frontiers. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7(3):311–340. doi: 10.2174/156802607779941314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greene ER, Huang S, Serhan CN, Panigrahy D. Regulation of inflammation in cancer by eicosanoids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 96(1–4):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming I. The cytochrome P450 pathway in angiogenesis and endothelial cell biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 30(3–4):541–555. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nie D, Tang K, Diglio C, Honn KV. Eicosanoid regulation of angiogenesis: role of endothelial arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase. Blood. 2000;95(7):2304–2311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, et al. Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+) cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors. Blood. 2000;95(3):952–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gehling UM, Ergun S, Schumacher U, et al. In vitro differentiation of endothelial cells from AC133-positive progenitor cells. Blood. 2000;95(10):3106–3112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Endothelial progenitor cells: characterization and role in vascular biology. Circ Res. 2004;95(4):343–353. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137877.89448.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giannotti G, Landmesser U. Endothelial dysfunction as an early sign of atherosclerosis. Herz. 2007;32(7):568–572. doi: 10.1007/s00059-007-3073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fadini GP, Schiavon M, Cantini M, et al. Circulating progenitor cells are reduced in patients with severe lung disease. Stem Cells. 2006;24(7):1806–1813. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma S, Kuliszewski MA, Li SH, et al. C-reactive protein attenuates endothelial progenitor cell survival, differentiation, and function: further evidence of a mechanistic link between C-reactive protein and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2004;109(17):2058–2067. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000127577.63323.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seeger FH, Haendeler J, Walter DH, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase downregulates endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2005;111(9):1184–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157156.85397.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lev EI, Leshem-Lev D, Mager A, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cell levels and function in patients who experienced late coronary stent thrombosis. Eur Heart J. 31(21):2625–2632. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issan Y, Hochhauser E, Kornowski R, et al. Endothelial Progenitor Cell Function Inversely Correlates With Long-term Glucose Control in Diabetic Patients: Association With the Attenuation of the Heme Oxygenase-Adiponectin Axis. Can J Cardiol. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abraham NG, Feldman E, Falck JR, Lutton JD, Schwartzman ML. Modulation of erythropoiesis by novel human bone marrow cytochrome P450-dependent metabolites of arachidonic acid. Blood. 1991;78(6):1461–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo AM, Janic B, Sheng J, et al. The cytochrome P450 4A/F-20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid system: a regulator of endothelial precursor cells derived from human umbilical cord blood. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 338(2):421–429. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abaci A, Oguzhan A, Kahraman S, et al. Effect of diabetes mellitus on formation of coronary collateral vessels. Circulation. 1999;99(17):2239–2242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.17.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407(6801):242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panigrahy D, Greene ER, Pozzi A, Wang DW, Zeldin DC. EET signaling in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 30(3–4):525–540. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9315-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Cathcart MC, Lysaght J, Pidgeon GP. Eicosanoid signalling pathways in the development and progression of colorectal cancer: novel approaches for prevention/intervention. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 30(3–4):363–385. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh NK, Kundumani-Sridharan V, Rao GN. 12/15-Lipoxygenase gene knockout severely impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis due to lack of Rac1 farnesylation. Blood. 118(20):5701–5712. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim GY, Lee JW, Cho SH, Seo JM, Kim JH. Role of the low-affinity leukotriene B4 receptor BLT2 in VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(6):915–920. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Shabrawey M, Mussell R, Kahook K, et al. Increased expression and activity of 12-lipoxygenase in oxygen-induced ischemic retinopathy and proliferative diabetic retinopathy: implications in retinal neovascularization. Diabetes. 60(2):614–624. doi: 10.2337/db10-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang DG, Renaud C, Stojakovic S, Diglio CA, Porter A, Honn KV. 12(S)-HETE is a mitogenic factor for microvascular endothelial cells: its potential role in angiogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211(2):462–468. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Donnell VB, Murphy RC. New families of bioactive oxidized phospholipids generated by immune cells: identification and signaling actions. Blood. 2012;120(10):1985–1992. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-402826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feletou M, Kohler R, Vanhoutte PM. Endothelium-derived vasoactive factors and hypertension: possible roles in pathogenesis and as treatment targets. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12(4):267–275. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abraham NG, Feldman E, Falck JR, Lutton JD, Schwartzman ML. Modulation of erythropoiesis by novel human bone marrow cytochrome P450-dependent metabolites of arachidonic acid. Blood. 1991;78:1461–1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo AM, Janic B, Sheng J, et al. The cytochrome P450 4A/F-20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid system: a regulator of endothelial precursor cells derived from human umbilical cord blood. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338(2):421–429. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.179036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Powell PK, Wolf I, Jin R, Lasker JM. Metabolism of arachidonic acid to 20-hydroxy-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid by P450 enzymes in human liver: involvement of CYP4F2 and CYP4A11. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:1327–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill E, Murphy RC. Quantitation of 20-hydroxy-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) produced by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes using electron capture ionization gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1992;21:249–253. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200210505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duh E, Aiello LP. Vascular endothelial growth factor and diabetes: the agonist versus antagonist paradox. Diabetes. 1999;48(10):1899–1906. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie D, Hillman GG, Geddes T, et al. Platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase in a human prostate carcinoma stimulates angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1998;58(18):4047–4051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bajpai AK, Blaskova E, Pakala SB, et al. 15(S)-HETE production in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells by hypoxia: Novel role for MEK1 in 15(S)-HETE induced angiogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(11):4930–4938. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks PC, Clark RA, Cheresh DA. Requirement of vascular integrin alpha v beta 3 for angiogenesis. Science. 1994;264(5158):569–571. doi: 10.1126/science.7512751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang DG, Chen YQ, Diglio CA, Honn KV. Protein kinase C-dependent effects of 12(S)-HETE on endothelial cell vitronectin receptor and fibronectin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1993;121(3):689–704. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang DG, Diglio CA, Honn KV. 12(S)-HETE-induced microvascular endothelial cell retraction results from PKC-dependent rearrangement of cytoskeletal elements and alpha V beta 3 integrins. Prostaglandins. 1993;45(3):249–267. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(93)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonipillai I, Nadler J, Vu EJ, Bughi S, Natarajan R, Horton R. A 12-lipoxygenase product, 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, is increased in diabetics with incipient and early renal disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(5):1940–1945. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.5.8626861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma K, Nunemaker CS, Wu R, Chakrabarti SK, Taylor-Fishwick DA, Nadler JL. 12-Lipoxygenase Products Reduce Insulin Secretion and {beta}-Cell Viability in Human Islets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 95(2):887–893. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki N, Hishinuma T, Saga T, et al. Determination of urinary 12(S)-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with column-switching technique: sex difference in healthy volunteers and patients with diabetes mellitus. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2003;783(2):383–389. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki N. Mass spectrometry-based quantitative analysis and biomarker discovery. Yakugaku Zasshi. 131(9):1305–1309. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.131.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steiner DR, Gonzalez NC, Wood JG. Leukotriene B(4) promotes reactive oxidant generation and leukocyte adherence during acute hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91(3):1160–1167. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walenta KL, Bettink S, Bohm M, Friedrich EB. Differential chemokine receptor expression regulates functional specialization of endothelial progenitor cell subpopulations. Basic Res Cardiol. 106(2):299–305. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0142-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Finkensieper A, Kieser S, Bekhite MM, et al. The 5-lipoxygenase pathway regulates vasculogenesis in differentiating mouse embryonic stem cells. Cardiovasc Res. 86(1):37–44. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gubitosi-Klug RA, Talahalli R, Du Y, Nadler JL, Kern TS. 5-Lipoxygenase, but not 12/15-lipoxygenase, contributes to degeneration of retinal capillaries in a mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2008;57(5):1387–1393. doi: 10.2337/db07-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartzman ML, Iserovich P, Gotlinger K, et al. Profile of lipid and protein autacoids in diabetic vitreous correlates with the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 59(7):1780–1788. doi: 10.2337/db10-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mezentsev A, Seta F, Dunn MW, Ono N, Falck JR, Laniado-Schwartzman M. Eicosanoid regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis in microvessel endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18670–18676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng J, Wu CC, Gotlinger KH, et al. 20-hydroxy-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid mediates endothelial dysfunction via IkappaB kinase-dependent endothelial nitric-oxide synthase uncoupling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 332(1):57–65. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.159863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishizuka T, Cheng J, Singh H, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid stimulates nuclear factor-kappaB activation and the production of inflammatory cytokines in human endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(1):103–110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.130336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo AM, Scicli G, Sheng J, Falck JC, Edwards PA, Scicli AG. 20-HETE can act as a nonhypoxic regulator of HIF-1alpha in human microvascular endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(2):H602–H613. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00874.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ward NC, Hodgson JM, Puddey IB, Beilin LJ, Croft KD. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is not associated with circulating insulin in lean to overweight humans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;74(2):197–200. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yousif MH, Benter IF, Roman RJ. Cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid play a role in the enhanced cardiac dysfunction in diabetic rats following ischaemic reperfusion injury. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2009;29(1–2):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2009.00429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theken KN, Deng Y, Schuck RN, et al. Enalapril reverses high-fat diet-induced alterations in cytochrome P450-mediated eicosanoid metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 302(5):E500–E509. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00370.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Theken KN, Schuck RN, Edin ML, et al. Evaluation of cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids in humans with stable atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 222(2):530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tepper OM, Galiano RD, Capla JM, et al. Human endothelial progenitor cells from type II diabetics exhibit impaired proliferation, adhesion, and incorporation into vascular structures. Circulation. 2002;106(22):2781–2786. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039526.42991.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sorrentino SA, Bahlmann FH, Besler C, et al. Oxidant stress impairs in vivo reendothelialization capacity of endothelial progenitor cells from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: restoration by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist rosiglitazone. Circulation. 2007;116(2):163–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.684381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]