Abstract

Applying the thermoacoustic (TA) effect to diagnostic imaging was first proposed in the 1980s. The object under test is irradiated by high-power pulses of electromagnetic energy, which heat tissue and cause thermal expansion. Outgoing TA pressure pulses are detected by ultrasound transducers and reconstructed to provide images of the object. The TA contrast mechanism is strongly dependent upon the frequency of the irradiating electromagnetic pulse.

When very high frequency (VHF) electromagnetic irradiation is utilized, TA signal production is driven by ionic content. Prostatic fluids contain high levels of ionic metabolites, including citrate, zinc, calcium, and magnesium. Healthy prostate glands produce more ionic metabolites than diseased glands. VHF pulses are therefore expected to generate stronger TA signal in healthy prostate glands than in diseased glands.

A benchtop system for performing ex vivo thermoacoustic computed tomography with VHF energy is described and images are presented. The system utilizes irradiation pulses of 700 ns duration exceeding 20 kW power. Reconstructions frequently visualize anatomic landmarks such as the urethra and verumontanum. TA reconstructions from three freshly excised human prostate glands with little, moderate, and severe cancerous involvement are compared with histology. TA signal strength is negatively correlated with percent cancerous involvement in this small sample size. For the 45 regions of interest analyzed, a reconstruction value of 0.4 mV provides 100% sensitivity but only 29% specificity. This sample size is far too small to draw sweeping conclusions, but the results warrant a larger volume study including comparison of TA images to the gold standard, histology.

Keywords: thermoacoustics, nondestructive (ultrasound/photoacoustic) testing, radiofrequency fields effects, biomedical imaging, cancer, ultrasound imaging

Introduction

AG Bell observed the thermoacoustic (TA) effect over a century ago, and application to diagnostic imaging was proposed in the 1980s (Bowen et al., 1981, Caspers and Conway, 1982, Nasoni et al., 1984). Thermoacoustic imaging is a hybrid technique that relies upon conversion of electromagnetic energy into mechanical energy via thermal expansion to create TA pressure pulses. TA imaging combines the high contrast of dielectric properties with the resolution of ultrasound, providing superior reconstruction stability and resolution over electromagnetic imaging and electric impedance tomography techniques. We have developed a benchtop thermoacoustic computed tomography (TCT) system for studying the clinical utility of thermoacoustic contrast mechanism generated by very high frequency electromagnetic irradiation. This system is optimized for imaging small tissue specimens with diameter 6 cm or less, such as the human prostate.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most challenging cancers for clinical diagnostic imaging techniques. Currently, PCa detection begins with a prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test and digital rectal examination of the prostate. Current imaging modalities have insufficient sensitivity and specificity to support image guidance for targeted biopsy and focal treatment of PCa (NCCN, 2014a). Systematic biopsy (Zukotynski and Haider, 2013) and surgical resection of the entire prostate are current standards of care. In contrast, breast cancer biopsies and lumpectomies based upon mammography images are focal and spare healthy tissue. In summary, neither PCa staging, treatment response nor active surveillance can currently be performed by current diagnostic imaging techniques alone (Outwater and Montilla-Soler, 2013).

Unfortunately, these deficiencies in diagnostic imaging affect a large volume of PCa patients. Current annual expectations are for nearly a quarter of a million PCa diagnoses in the U.S. alone (Society, 2013) and over 300,000 deaths worldwide (Ferlay et al., 2012).

Diagnostic techniques are not limited to imaging. Until the advent of the PSA test the primary method of diagnosis was palpation, to qualitatively assess tissue stiffness. PSA testing was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1994 but received a “D” rating from the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force in 2012 (Moyer, 2012). For several decades it has been understood that prostatic fluids contain high levels of citrate, zinc, calcium, magnesium, and other metabolites which are positively correlated to each other (Kavanagh, 1985). Healthy prostate glands produce fluid with threefold higher ionic content than blood and plasma, whereas diseased glands produce prostatic fluid that is similar in conductivity to blood. In particular, numerous studies have established that PCa suppresses citrate and zinc in the peripheral zone as reported in the review article (Costello and Franklin, 2009). PCa detection by in vitro nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy of expressed prostatic fluid yielded an area under the receiver operator characteristic curve of 0.89 (Serkova et al., 2008). Unfortunately, neither PSA nor in vitro spectroscopic metabolite detection provides spatial localization of tumors within the prostate.

Current PCa imaging techniques

B-mode ultrasound imaging is typically relegated to merely defining the prostate boundary because acoustic properties of healthy and cancerous prostate tissue are well matched, so image contrast between them is poor. Biopsy of the prostate is required for histologic verification of the PCa diagnosis as well as assessment of disease aggressiveness. Ultrasound is used for systematic biopsy needle placement rather than cancer detection. Imaging to identify disease extent is typically performed only after histologic confirmation, and in most cases is limited to patients whose PCa is suspected to extend beyond the prostate gland but is not yet metastatic. Contrast enhanced ultrasound and manual compression ultrasound elastography used together increased the positive predictive value of cancer detection from 65.1% to 89.7% (Brock et al., 2012). Elastography visualizes tissue stiffness and can be implemented via many methods reviewed in (Parker et al., 2011). Operator dependence has limited clinical utility of manual compression elastography, however. Mechanical production of shear waves minimizes operator dependence of shear wave elastography. Good sensitivity and specificity have been reported (Ahmad et al., 2013), although false positives were found in regions of calcification (Barr et al., 2012).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results vary wildly, based upon MRI technique, magnet field strength, choice of receive coils and reader experience (Rooij et al., 2014). Magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) provides spatial localization of citrate and other metabolites. Two decades have past since MRSI was first applied to prostate cancer imaging (Narayan and Kurhanewicz, 1992) and scores of prostate MRSI papers have followed. Unlike in vitro spectroscopy, MRSI only provides only relative levels of metabolites and cannot quantify metabolite concentrations. Additionally, crosstalk between spectral peaks is problematic. A meta-analysis performed in 2008 found little evidence to recommend clinical adoption of MRSI for diagnosis or targeted biopsy (Umbehr et al., 2009), and more recently a cost-benefit meta-analysis performed in the United Kingdom found expected incremental life years of no more than 0.006 years due to any type of MR-guided biopsy over ultrasound guidance (Mowatt et al., 2013). More recently, good sensitivity (96.4%) but terrible specificity (7.6%) were reported in a MRI-ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy study (Salami et al., 2014) fraught with selection and detection bias (Warlick, 2014). Clinical practice guidelines issued by both the European Association of Urology and the USA's National Comprehensive Cancer Network withhold recommendation pending validation in clinical trials for image guided biopsy (NCCN, 2014b, EAU, 2014, Eberhardt et al., 2013). Multi-parametric MRI has also been proposed for confirming eligibility for active surveillance (Stamatakis et al., 2013) but the American College of Radiology withholds recommendation (Eberhardt et al., 2013).

In summary, no imaging method has gained widespread acceptance for PCa imaging.

TA contrast mechanism as a function of electromagnetic irradiation frequency

The TA contrast mechanism is a complicated function of thermal, mechanical, and dielectric tissue properties. It relies upon conversion of electromagnetic (EM) energy into mechanical energy. First, EM energy must penetrate into tissue so that absorption of EM energy causes sufficient tissue heating and thermal expansion to generate an outgoing pressure pulse. Therefore, both EM and acoustic attenuation limit depth penetration. Neglecting acoustic attenuation, TA signals are governed by the acoustic wave equation

| (1) |

where vs represents sound speed and S(x, t) is the thermoacoustic source.

The TA contrast mechanism driven by VHF irradiation differs from that of photo- and microwave-induced contrast. Optical pulses used for photoacoustics heat proportionally to haemoglobin content and have the ability to discriminate between oxy- and de-oxy haemoglobin. Microwaves heat pure water efficiently, whereas VHF irradiation heats proportionally to ionic content. In the VHF regime, the source term is driven by electrical conductivity. VHF heating with good spatial uniformity permits simplification of the source term in Eq. 1 to

| (2) |

where Eo represents the known amplitude of the electric field, I(t) is the temporal envelope of the irradiation pulse. σ(x) is electrical conductivity, is the dimensionless Grueneisen where β and C represent thermal expansion coefficient and specific heat capacity, respectively. An ideal system would irradiate impulsively so that I(t) = δ(t), making the source term a function of x alone,

| (3) |

The TA source term is therefore the product of applied electric field strength with two tissue parameters, the Gruneisen and electrical conductivity. TA pressures can be written in terms of spherical means of S

| (4) |

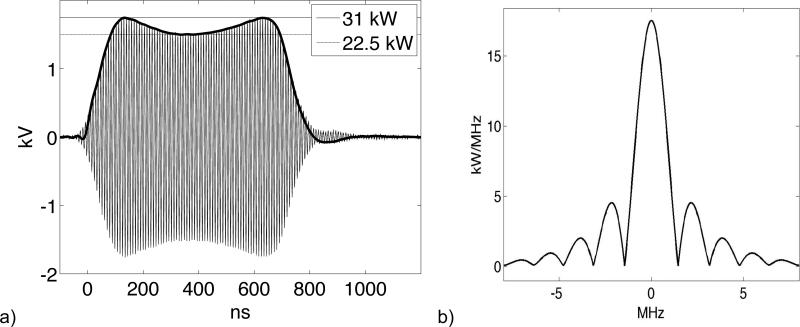

where M is the mean value operator, taking the spherical mean of S over a sphere of radius vs t centered at point x. TCT images of the source term, S, are reconstructed tomographically from measurements of the pressure at points x on a measurement aperture surrounding the region of interest. Bandlimiting of the TA pulses by the irradiation pulse envelope, I, can be analyzed analytically (John, 1981) or numerically (Lou et al., 2011). Ultrasound receivers further bandlimit measurements. These effects bandlimit tomographically reconstructed images commensurately (Anastasio et al., 2007). The pulse envelope and power spectral density which bandlimits TA pulses generated in our experimental system are shown in Figure 1. Voltages are measured using a line section (Bird 4715) outfitted with 50 dB attenuating slugs (Bird 4274). The voltage plotted in Figure 1(a) accounts for attenuation. This data is used to compute the power spectral density plotted in Figure 1(b).

Figure 1.

(a) 700 ns AC irradiation pulse (thin) and pulse envelope, I (thick). (b) Power spectral density (PSD).

TA bandwidth and depth penetration as a function of EM irradiation frequency

In practice, irradiation pulsewidth tends to decrease with irradiation frequency because ultrawideband irradiation is difficult to achieve and efficiently utilize. Short pulses used in photoacoustics approximate a δ-function well, as do ultrawideband pulses. 10 ns pulsewidths with VHF (Razansky et al., 2010) and microwave (Lou et al., 2012) center frequencies correspond to a power spectral density with essential bandlimit of 100 MHz. Numerical investigation of even shorter UWB pulses indicates poor depth penetration of the EM field and initial pressure distribution (Tao et al., 2006). Even if extremely broadband TA pulses can be generated deep in soft tissue, acoustic attenuation will suppress high frequencies in the TA pulses. Clinical ultrasound systems are therefore optimized over the 1-15 MHz regime. Ideally, TA pulse generation would match the clinical regime by irradiating with pulse widths of approximately 65 ns. Unfortunately, current state of the art in TA imaging pulse widths are either below 10 ns or else exceed 300 ns in the microwave regime, 500 ns in the ultra high frequency (UHF) regime, and 700 ns VHF pulses as utilized below. Even the 300 ns microwave pulse widths bandlimit TA pulses to 3.3 MHz, which is at the low end of the clinical US frequency range.

EM frequency affects the source term in many ways including depth penetration and uniformity of EM deposition. Optical depth penetration is only 5.7 mm (Wang and Wu, 2007), whereas microwave depth penetration extends to a few cm (Tao et al., 2006, Yan et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2012). Optical fluence decreases smoothly with distance from the laser source, whereas microwaves suffer diffraction and develop standing waves which can cause signal drop-out in microwave induced TCT systems (Li et al., 2008). 9.4 GHz irradiation has produced A-line TA imaging of thin specimens (Wang et al., 1999) and 5.66 GHz irradiation has produced a projection image (Olsen and Lin, 1983). Nevertheless, foreign objects with low ultrasound contrast were detected in vivo in a mouse model using both 6 GHz and 1.2 GHz (Nie et al., 2009), although the 6 GHz irradiation provided less depth penetration that 1.2 GHz. 6 GHz irradiation was used to study samples of dimension no more than 15 mm (Lou and Xing, 2010). Promising images of specimens less than 5 cm in diameter have been obtained using 3 GHz microwave radiation (Ku and Wang, 2001, Jin et al., 2005, Xu and Wang, 2002). 1.2 GHz irradiation has produced encouraging ex vivo results for detecting breast tumors (Nie et al., 2008) and renal calculi (Cao et al., 2010). Ultra high frequency radiation at 434 MHz provides sufficient penetration depth to penetrate adipose breast tissue with adequate uniformity for in vivo TCT (Kruger et al., 2000). However, imaging large internal organs may require irradiating with frequencies in the VHF regime of 30 – 300 MHz, which provides superior depth penetration and uniformity. 7.0 Tesla MRI systems that propagate 300 MHz successfully image the adult head but struggle to provide adequate field uniformity in the abdomen. Body coils in 1.5 Tesla and 3.0 Tesla MRI scanners propagate circularly polarized EM energy with carrier frequencies 64 MHz and 128 MHz into large patients with excellent homogeneity and depth penetration. The price exacted for large field of view TA imaging by VHF irradiation is weak TA signal generation.

Application to Prostate Cancer Imaging

PCa is a compelling application for TA imaging. The well-matched mechanical properties that hinder B-mode ultrasonic imaging of PCa simplifies image reconstruction because we can safely assume constant sound speed. Additionally, preliminary measurements of specific heat capacity, C, did not differentiate healthy from diseased prostatic tissue at body temperature (Patch et al., 2011). Therefore, we assume that only the thermal expansion coefficient, β, and EM energy loss drive the TA contrast mechanism in the prostate. Several groups have applied photoacoustic imaging to studies of brachytherapy seeds in tissue phantoms (Harrison and Zemp, 2011, Kuo et al., 2012, Su et al., 2011). Poor depth penetration of optical radiation may require transurethral light delivery and highly optimized reconstruction (Lediju Bell et al., 2013), however. In vivo studies of the canine prostate have also been performed (Wang et al., 2010, Patterson et al., 2010). Multispectral ex vivo photoacoustic images of 3-5 mm thick fresh human prostatic tissue performed immediately after gross sectioning could discriminate PCa from healthy prostatic tissue and also from benign prostatic hyperplasia based upon deoxyhaemoglobin content (Dogra et al., 2013).

Prostate cancer may be particularly well suited to TA imaging using VHF heating which is driven by ionic content. Extremely high levels of citrate in prostatic fluid cause other ions to accommodate and restore electrochemical balance (Kavanagh et al., 1982). Ionic content of prostatic fluids produced in a healthy gland is approximately three times that of plasma and blood. PCa suppresses citrate, and therefore overall ionic content of prostatic fluids. This relationship applies also to tissue in the peripheral zone (PZ) where most prostatic fluid is produced and most PCa tumors develop (Costello and Franklin, 2009). The central zone is neither a site of significant prostatic fluid production nor high incidence of PCa. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) frequently arises in the central zone, and elevates citrate and zinc levels to that found in healthy peripheral zone tissue. In vitro assays of expressed prostatic fluids can therefore differentiate between the presence of BPH and PCa (Kumar et al., 2013), but cannot localize tumors within the prostate. TA imaging offers the possibility of localizing tumors, as well as differentiating BPH from cancer. TA image values in the central zone exceeding that expected from normal plasma should indicate the presence of BPH, whereas in the peripheral zone thermoacoustic image values comparable to plasma are expected to indicate PCa.

To study the TA contrast mechanism in specimens with diameter less than 6 cm, a benchtop imaging system has been optimized for ex vivo imaging. We present preliminary results comparing TCT images to the gold standard, histology slides.

Materials and Methods

Ex vivo TCT was performed much as described in (Roggenbuck et al., 2013b, Eckhart et al., 2011), but in a benchtop imaging system optimized for imaging smaller tissue specimens (Figure 2). The testbed has dimensions of a TE103 cavity, but with well-matched coupling irises at input and output ports, allowing efficient transmission of a TE10 pulse through the testbed to a load (Fallon et al., 2009). The system operates in transmission mode, with EM propagation direction perpendicular to the axial direction of the receive transducers as depicted in Figure 3. For imaging small specimens, such as human prostates, the testbed cross section was reduced to 6 cm x 19 cm, concentrating the electric field and generating stronger TA pulses. Additionally, reducing the testbed width from 10 cm to 6 cm allowed the transducers to be positioned closer to the specimen, increasing SNR of the TA measurements. EM parameters were optimized for this smaller benchtop system. The EM irradiation pulse width was reduced to 700 ns, increasing the essential band-limit of TA pressures to 1.4 MHz. Incident and reflected voltages were measured at both input and output ports of the testbed to monitor EM performance of the system. The custom EM amplifier (QEI, VHF50KP), line sections and rigid copper coaxial connections (EIA 1 5/8”) remained unchanged from our previous work. A digital oscilloscope (Tektronix DPO7104) with onboard personal computer acquired both EM and TCT data. The scan process was driven by LabView software running on the oscilloscope. The EM amplifier and testbed were enclosed in a 100 dB Faraday cage (ETS Lindgren) outfitted with a penetration panel containing coaxial connectors for data lines as well as one USB connector for a communication line as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Aerial view of benchtop imaging testbed. “×” indicates the gantry axis of rotation and translation.

Figure 3.

TCT data acquisition geometry. Black solid circle indicates the ultrasound receiver trajectory relative to the specimen. VHF irradiation pulse propagates perpendicular to the axes of the transducers. Thin white circles indicate the surface of spherical integrals measured by upper (solid) and lower (dashed) transducers.

Figure 4.

Schematic of TCT system. Thick solid indicates TA data lines. Thin solid indicates low power VHF data lines. Hollow arrows indicate high-power VHF pulse. Thick dashed indicates communication lines between LabView, signal generator, and stepper motor.

EM Power Measurements

To control for systematic variations in TA signal strength due to amplifier power output, incident and reflected power at both input and output ports of the testbed was monitored by recording voltages on a 4-channel digital oscilloscope set to 1 GHz bandwidth and 200 ps sampling rate. A pulse incident upon the input port is shown in Figure 1 (left). 4-channel control data taken immediately before and/or after loading the testbed with a prostate recorded both incident and reflected voltages at each port. During TA data acquisition, however, two channels were used to record TA pulses. The remaining two channels were used to monitor incident power at input and output ports. Voltages were measured between acquisitions of single-slice TA sinograms. 24 realizations were acquired for each control measurement, and six realizations were acquired between TA sinograms.

TCT Data Acquisition

To improve stability of the tomographic gantry the testbed design was rotated from that described in (Eckhart et al., 2011). Specimens were suspended below a dual motion stepper motor (Haydon Kerk) by a stiff monofilament surgical suture, ensuring a stable vertical axis of rotation and translation. Spatial encoding was obtained by rotating and translating the specimen in step-and-shoot mode. The translation increment was 3 mm, consistent with the 3 mm distance between histology levels. Image planes were acquired from apex to base. The rotation increment was 1.8° between tomographic views. To avoid “jerking” the specimen, 64 subrotations were each followed by a 25 ms delay. After rotating the full 1.8° increment another 500 ms delay allowed the specimen to come to rest before data acquisition commenced. The EM pulse repetition frequency was 100 Hz and 64 TA pulses were averaged to suppress noise as depicted in Figure 5. For each tomographic view, more than 2 seconds were required for specimen repositioning, whereas data acquisition required less than 1 second. Saving data to disk and communication within LabView required additional time, so total dwell time at each tomographic view was approximately 5 seconds. Partial-scan TCT sinograms, typically containing only 140 of 200 views, were acquired by each transducer over a period of approximately 12 minutes per acquisition slice. To minimize specimen heating, duty cycle was minimized by irradiating only during data acquisition. EM irradiation was not applied during specimen positioning, LabView communication, and saving data to disk.

Figure 5.

TA pulses as displayed on and recorded by oscilloscope. Single realization in thin black, average of 64 pulses in thick yellow.

Two identical 2.25 MHz focused single-element transducers with 0.5” diameter and 0.8” distance to focus (Olympus V306) were positioned on opposite sides of the specimen. The acoustic couplant was deionized water mixed with a concentration of 15 g/L glycine powder. Glycine powder was added to minimize water absorption by the tissue, which would impair histologic analysis. Glycine powder did not affect speed of sound or attenuation as measured during system validation. TA pulses were amplified 54 dB by a low noise preamplifier (Olympus 5662) positioned outside of the Faraday cage to shield it from electromagnetic interference (EMI). Sensitivity of similar transducers amplified by only 40 dB was approximately 1 mV/Pa (Pachauri et al., 2008), corresponding to 5 mV/Pa when amplified by 54 dB. Averaged TA pulses like that plotted with the thick line in Figure 5 were written to disk by the digital oscilloscope. Bandwidth and sampling rate were lowered to the lowest available settings compatible with both LabView and TekTronix software, 20 MHz and 10 ns.

The focus of each transducer was treated as a point receiver (Li et al., 2006), acquiring circular integrals of the source term, S(x), as depicted by thin white lines in Figure 3. Data from the transducers was carried by doubly-shielded coaxial cables, which were additionally shielded using commercial aluminum ductwork. Coaxial cables and aluminum ductwork were grounded at the penetration panel.

This acquisition system is less costly and more sensitive than clinical ultrasound transducers with element diameter less than 1 mm, but suffers from two drawbacks. It is sensitive to EMI and acquisition using only two single element transducers requires lengthy scan times. To shield the transducers from the EM irradiation pulse, transducers were recessed 1 cm inside cutoff chimneys, so that the focus protruded approximately 5 mm into the testbed volume, as depicted in Figure 3. Prostate tissue degrades slowly after excision and is therefore suitable for studies of the fundamental contrast mechanism in benchtop systems with lengthy scan times, in particular when the specimens remain chilled (one method to reduce autolysis). Autolysis, readily recognized by light microscopy, was not observed in any of the specimens upon light microscopic examination. It is therefore evident that the cell membranes remained intact. Should the contrast mechanism prove clinically useful in large volume ex vivo studies, development of sophisticated clinical prototypes will be warranted.

TCT Image Reconstruction

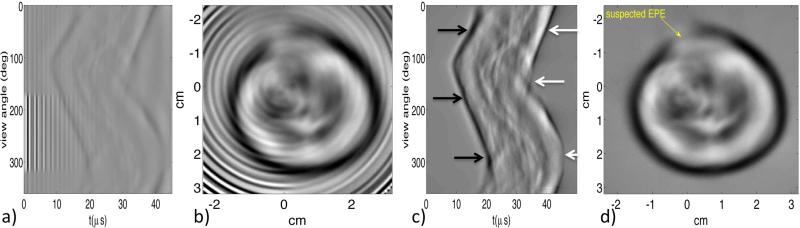

Image reconstruction was performed by filtered back projection, with significant data correction applied prior to back projection (Roggenbuck et al., 2013a). Each TA projection was bandpass filtered with a bandpass of 100 kHz to 5 MHz and then Hilbert transformed. Sinogram-space “ringfix” correction was applied to remove signal due to EMI as shown in Figure 6. Acoustic scattering within the prostate is minimal and care was taken to remove signal due to acoustic reflections at the prostate/couplant boundary. EMI causes high-frequency vertical streaks in sinograms and rings in reconstructed images, whereas multiple reflections at the prostate-couplant interface typically create a low frequency “halo-effect” around the boundary of the specimen. Corrected measurements are referred to as pcorr.Finally, partial-scan TA sinograms were smoothly combined to simulate complete 360-degree acquisitions by a single transducer. Because the transducers are directional, backprojection was performed in plane, yielding the approximate reconstruction formula

| (1 |

Here y(θ) = (R cosθ, R sinθ, z) are detector trajectory points where reconstruction point x = (x, y, z), R is the radius of the acquisition trajectory and n is the inward pointing unit normal. In this system R ~ 25 mm because the transducer focus protrudes beyond the sidewall of a 6 cm wide testbed.

Figure 6.

Single-element transducer measurements and reconstructions, before and after EMI and multiple reflection corrections. Bandpass filtered sinogram (a) and reconstructed image (b) without correction. (c) Sinogram corrected for EMI and multiple acoustic reflections. Leading compressional edge of the pulse and primary rarefactional region indicated with black and white arrows, respectively. (d) Image reconstructed from corrected sinogram, with site of suspected extraprostatic extension (EPE) indicated by yellow arrow.

Specimen Acquisition and Handling

All specimens were from biopsy-confirmed PCa patients who received radical prostatectomy as part of their normal care. Inclusion criteria were preoperative stage T2a, b, c or PSA>9 or primary Gleason>3. An additional requirement that the prostate diameter be limited to 6 cm in left-right (LR) and anterior-posterior (AP) directions ensured that each specimen would fit inside the benchtop imaging system. The Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin approved this prospective study. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

More than three-dozen specimens were scanned and most were removed by robotic surgical technique. All three of the specimens sent for thorough histologic comparison were removed robotically. During robotic surgery, 3 mm surgical staples were affixed along a “staple line” on the anterior portion of the prostate to control bleeding. After the vascular attachments of the prostate were divided, the prostate and attached seminal vesicles were placed in a plastic bag and remained unperfused inside the warm abdomen for approximately one hour until completion of the surgical reconstruction. The prostate was then removed from the body and the staple line was removed from the prostate. The remaining specimen was placed in a biohazard bag and packed in wet ice for transport to the benchtop imaging system. Deviations from this procedure included: failure to completely remove the staple line, imaging with 3.5 MHz transducers rather than 2.25 MHz, EM amplifier malfunction, templogger failure and oversized specimen (greater than 6 cm in left-right or anterior-posterior dimension). Although these data sets cannot be included in statistical analysis comparing TA signal production the surgical staples and higher-frequency transducer demonstrate good in-plane resolution.

Care was taken to preserve the fresh prostate tissue specimens for histologic analysis required for patient care. Imaging commenced within 60-90 minutes and data acquisition was limited to four hours. Specimens were immersed in acoustic couplant that was chilled to prevent autolysis (cell breakdown occurring after cell death). Temperatures were recorded by a templogger every minute during data acquisition and varied from 3 °C to 13 °C. Prostate tissue is denser than water, but vesicles are often buoyant. Therefore, the vesicles were bundled together using small rubber bands as shown in Figure 4. A glass bead was often attached to ensure that they would hang directly below the prostate. Immediately after data acquisition specimens were formalin-fixed. The entire prostate was sliced at 3 mm intervals and submitted for diagnostic histological processing.

Histology

Diagnostic pathology reports were available for all specimens. These diagnostic reports provide only percent cancerous involvement averaged throughout the entire gland, largest dimension of largest tumor, and Gleason grade. Diagnostic reports also indicate whether tumor extended beyond the capsule of the prostate (extraprostatic extension, EPE) or the presence of a positive surgical margin, but do not typically specify location or dimension of the interruption of the prostate capsule. Unfortunately, none of these diagnostic metrics provide spatial information that can be directly correlated to axial TCT reconstructions.

Histology slides from three prostate specimens that generated clear anatomical markers in TCT images were selected for labor-intensive reading and annotation by a fellowship-trained genitourinary pathologist with greater than 6-years experience (DH). The specimens selected contained little, moderate, and extensive disease, respectively. Additionally, TCT images of each clearly display the verumontanum. Each cancerous region in histology was assigned a Gleason score, which is the sum of primary and secondary Gleason grades, ranging from 1 (least aggressive) to 5 (most aggressive). The primary Gleason grade represents the Gleason pattern that constitutes the greatest volume of cancer. The secondary Gleason grade corresponds to the second most prevalent Gleason pattern. Primary and secondary Gleason grades in the specimens examined ranged from 3 (least aggressive) to 5 (most aggressive). Due to the variety of PCa treatment options, patients referred for surgery typically present with Gleason scores of 6 or 7. All specimens examined in this study were Gleason score 6 or 7. Regions of inflammation (INFL), atrophy, nodular hyperplasia, high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGpin) and extraprostatic extension (EPE) were also noted. The type of tissue was annotated directly on histology slides as well as on a detailed report form. Descriptions of cancerous regions included percentage of cancer within the region (Table 1, 3rd column) and Gleason grade of cancer within the region (column 4). Additionally, the percentage of each Gleason grade contained within the region was provided (columns 5-6).

Table 1.

TCT reconstruction value vs. Gleason Scores

| specimen | ROI | % cancer | GL score | % Gl 3 | % Gl 4 | μ (mV) | σ (mV) | T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 80 | 3+4 | 90 | 10 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 6.7 |

| 2 | 100 | 4+3 | 40 | 60 | 0.13 | 0.12 | ||

| 3 | 10 | * | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 90 | 3+4 | 90 | 10 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 7.6 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.09 | |||||

| 3 | 100 | 4+3 | 20 | 80 | 0.27 | 0.08 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 0.24 | 0.14 | |||||

| 3 | 1 | 30 | 3+3 ** | 100 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 11.6 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0.49 | 0.13 | |||||

| 3 | 0 | cystic | 0.52 | 0.14 | ||||

| 4 | 0 | 0.49 | 0.18 | |||||

less than 10% HGpin, many foci of cystic change associated with acute and chronic inflammation

also significant inflammation

TCT reconstruction slices were correlated to histology levels using the wedge-shaped verumontanum as the primary anatomical landmark. Although the step size between histology and TCT reconstruction slices were both 3 mm, the offset between histology and TCT is unknown. Additionally, the fixation process deforms tissue, further confounding correlation between histology and reconstruction slices.

Two types of regions of interest (ROIs) were assigned for two different purposes. The posterior region approximating the entire PZ was annotated as one large ROI on each TCT image slice as shown in Figure 7(a). This was performed for specimens for which temperature data was available. All prostates in this study contained biopsy-confirmed cancer, but we have access to detailed histologic analysis for only a few specimens. The 25 “controls” are simply specimens for which detailed histology is unavailable. This was done to determine whether temperature fluctuations during the 4-hour scan process affect TA signal production.

Figure 7.

Designation of regions of interest. (a) Control specimen marked with single ROI approximating the posterior PZ. (b) Overlay of histology slides onto the corresponding thermoacoustic image of specimen #3.

To determine whether thermoacoustic signal strength is correlated to disease state, the peripheral zone was divided into regions corresponding to different tissue types noted by the pathologist. TCT imaging of the whole fresh prostate was performed prior to formalin fixation, which can deform tissue. Therefore, TCT images represent the “true” morphology. Regions marked on histology slides were registered to corresponding regions on TCT images using anatomical landmarks as control points. A piecewise linear scheme was used to overlay histology slides upon the TCT reconstructions as shown in Figure 7(b). TCT image resolution is low, so only coarse subdivision was performed as shown in Figure 8(d-f).

Figure 8.

TCT reconstructions vs. histology slides. ROIs segment the posterior PZ. Display window of TCT images is [-0.7 0.7] mV. Arrows indicate the verumontanum. (a,d) Specimen #1 suffered approximately 80% involvement. (b,e) Specimen #2 had less than 50% involvement. (c,f) Specimen #3 had minimal cancerous involvement.

Electric field strength is proportional to voltage and power is proportional to voltage squared. Because the rigid coaxial connections to the testbed were standard 50 Ohm, power was computed simply by correcting measured voltages for attenuation and then dividing the time averaged voltage squared during each pulse by 50 Ohms.

Results

Thermoacoustic image values in select regions of the PZ were correlated to disease state for three histology specimens. Image values averaged throughout the PZ were independent of temperature but weakly dependent on overall cancerous involvement throughout the entire prostate.

TA reconstruction values – correlation with disease status

In reconstructions from specimens 1-3 thermoacoustic signal strength decreases with tumor involvement. Reconstruction slices that clearly show the verumontanum are compared to histology in Figure 8. Regions marked with yellow approximate regions of involvement as annotated on the corresponding histology slide. Results are quantified in Table 1. Gleason grade and percent involvement of each grade are listed in columns 4-6. Columns 7 and 8 contain mean (μ) and standard deviation (σ) of TCT reconstruction values. Because glycine solution has very low electrical conductivity, reconstruction values in the background region outside the prostate should be zero. Large ROIs placed in the background regions have mean reconstruction values of 5e-3 mV or less. The least diseased specimen, #3, generated mean reconstruction values of 0.49 mV throughout most of the PZ except for a small region of low-grade cancer, which corresponds to slightly suppressed mean reconstruction value of 0.34 mV. Strongest average reconstruction values from the PZ of the most diseased specimen, #1, were very nearly within one standard deviation of zero at 0.13 ± 0.12 mV.

Average reconstruction values for healthy regions in specimen #3 are four-fold greater than the values for cancerous regions in specimen #1. 45 ROIs were analyzed from these three specimens. Within this small sample, using a cut-off value of 0.4 mV would yield perfect sensitivity of 24/(24+0) = 100% but poor specificity of 6/(6+15) = 6/21 = 29% for PCa detection.

TA reconstruction values – temperature dependence

Maintaining thermal control during data acquisition was difficult, not only due to thermal heating of the specimen but also heat emitted by the VHF amplifier. Temperatures fluctuated over a range of 10 °C, but were concentrated generally in the 5-8 °C range. Temperatures were recorded during acquisition and correlated to image slice using time stamps on data files (Table 1, column 9). Mean reconstruction values from posterior regions approximating the peripheral zones are plotted with respect to testbed temperature during acquisition in Figure 9(a). Each different symbol-color combination represents a different prostate. Solid red symbols represent the three prostates selected for thorough histologic annotation. Hollow symbols (black, blue and magenta) represent controls. Linear least squares fits for the three prostates selected for detailed histology (solid red line) as well as the 25 control specimens are plotted (dashed black line). Temperature dependence of the large group of 308 slices from 27 prostates is nearly zero, as the dashed black line is nearly horizontal. Therefore, we conclude that the apparent temperature dependence within the small set of only 37 slices from three specimens is spurious.

Figure 9.

Average reconstruction values in posterior PZ. Solid symbols for three selected prostates with extensive, moderate, and minimal disease are diamond, triangle, and circle. Hollow symbols represent 25 control specimens. (a) Thermoacoustic average value versus temperature. (b) Thermoacoustic average value versus overall cancerous involvement.

TA reconstruction values – dependence upon percent overall cancerous involvement

The same reconstruction values are plotted against overall percent involvement throughout the entire prostate as stated in the clinical pathology report. Therefore, several symbols representing the mean reconstruction values in each of several histology levels are plotted in a vertical line above the overall percent involvement in Figure 9(b). A linear fit to these data shows weak dependence on overall percent cancer throughout the prostate.

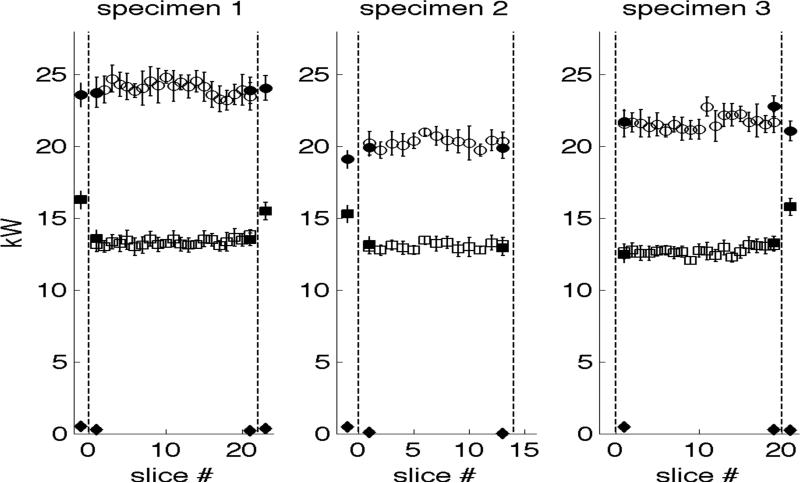

TA reconstruction values – dependence upon incident EM power

EM power levels computed from measured voltages ranged from 20-25 kW as plotted in Figure 10. Error bars represent one standard deviation above and below the mean. Measurements taken when the testbed was loaded with the prostate are plotted between the vertical dashed lines. Measurements taken before or after loading the testbed are plotted to the left and right, respectively. Circles and squares represent incident power at input and output ports, respectively. Diamonds represent reflected power at the input port. Hollow symbols represent 2-channel data acquired during TA data acquisition; solid symbols represent 4-channel control measurements, which include reflected power. Note that these values represent power incident and reflected upon the entire system, glycine dielectric and prostate, rather than an individual reconstruction slice.

Figure 10.

EM power measurements. Circles and squares represent incident power at input and output ports, respectively. Diamonds represent reflected power at the input port. Hollow symbols represent 2-channel data acquired during TA acquisition; solid symbols represent 4-channel control measurements acquired before and after imaging.

Discussion

The low-resolution reconstructions presented here hold promise that the contrast mechanism may provide clinically useful information. In the specimens selected for detailed histology, TA signal strength is suppressed in cancerous regions, corroborating conventional wisdom that metabolite production by cancerous glands is suppressed. Reconstructions routinely visualize structures such as the verumontanum mid-gland, as well as the urethra near the apex and base. Despite band-limitations induced by a 700 ns EM irradiation pulse, small ducts were sometimes visible.

Besides the small sample size there are several limitations to this preliminary ex vivo study. The 6 cm testbed width restricted our study to prostates of dimension 6 cm or less in both L/R and A/P directions. This may have skewed our pool of specimens, but VHF excitation can easily provide depth penetration sufficient for imaging larger prostates. Loss of prostatic fluid during specimen procurement and imaging is expected to be low. Because specimens were removed robotically, a small amount of prostatic fluid may have been expressed as the prostate was extracted through a small incision. The capsule is designed to protect an organ, and mitigate fluid transport across its boundary. Ionic loss at sites of EPE and positive margins could artificially suppress TA signal generation and future work with a large number of samples should exclude these regions. A lesser concern is lack of blood flow during ex vivo imaging. Although the prostate is highly vascular, flow rates are relatively slow and radical prostatectomy specimens retain ‘steady state’ blood volume within the prostate microvasculature. Finally, we were forced to keep the specimen chilled to minimize autolysis. Temperature dependence of the parameters comprising the Gruneisen and dielectric properties of water is well understood. Temperature dependence of these parameters for blood and soft tissue is less well understood, but is unlikely to account for the 400% increase in signal generated by specimen #3 over #1. Furthermore, signal produced in the PZ of 25 control specimens was nearly independent of temperature, increasing by less than 20% from 3 °C to 13 °C. In vivo scanning at body temperature should increase TA signal strength somewhat over that generated by the chilled specimens imaged in this study.

The weak dependence of TA reconstruction values upon percent overall cancerous involvement shown in Figure 9b is encouraging. A correlation is expected, based upon the hypothesis that PCa suppresses ionic content of prostatic fluid. Perfect correlation, however, would indicate that TCT could only identify overall cancerous involvement, but not localize individual tumors.

Although high-power measurements are difficult to make accurately, the results in Figure 10 give confidence that weak signal generation by specimen #1 was due to the specimen itself rather than experimental factors. Incident power measurements varied by approximately 20% between the specimens and were greatest for specimen #1, although specimen #1 generated the weakest TA signal. Additionally, these measurements verify good EM system performance. Reflected power was extremely low in all control measurements. Furthermore, loading the testbed with a lossy tissue specimen decreases power transmitted through the testbed, and the power lost within the specimen gives rise to TA signal. Reflected power at the input port often decreases when the testbed is loaded with a specimen. Although some EM power may be reflected at the couplant-tissue interface, lossy specimens often act as power sinks, reducing overall reflected power.

Unlike microwave and optical heating, VHF radiation provides excellent depth penetration. The rarefaction portion of each TA pulse was clearly visible throughout most sinograms, demonstrating that the TA pressures produced were sufficiently strong to propagate through the entire gland.

If more these preliminary results are corroborated by larger studies then development of a working clinical prototype will be warranted.

Acknowledgements

This project was partially supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number 8UL1TR000055. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

SKG was supported by UW-Milwaukee's Office of Undergraduate Research.

List of Acronyms

- BPH

benign prostatic hyperplasia

- EPE

extraprostatic extension

- EM

electromagnetic imaging

- EMI

electromagnetic interference

- HGpin

high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia

- INFL

inflammation

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MRSI

magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging

- PCa

prostate cancer

- PSA

prostate-specific antigen

- PZ

peripheral zone

- ROI

region of interest

- TA

thermoacoustic

- TCT

thermoacoustic computerized tomography

- VHF

very high frequency

REFERENCES

- AHMAD S, CAO R, VARGHESE T, BIDAUT L, NABI G. Transrectal Quantitative Shear Wave Elastography in the Detection and Characterisation of Prostate Cancer. Surgical Endoscopy. 2013;27:3280–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2906-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANASTASIO M, ZHANG J, MODGIL D, LA RIVIÈRE PJ. Application of inverse source concepts to photoacoustic tomography. Inverse Problems. 2007;23:S21–36. [Google Scholar]

- BARR R, MEMO R, SHAUB C. Shear Wave Ultrasound Elastography of the Prostate Initial Results. Ultrasound Quarterly. 2012;28:13–20. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e318249f594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWEN T, NASONI L, PIFER AE, SEMBROSK GH. IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. Vol. 2. Chicago, IL.: 1981. Some Experimental Results on the Thermoacoustic Imaging of Tissue Equivalent Phantom Materials. [Google Scholar]

- BROCK M, EGGERT T, PALISAAR R, ROGHMANN F, BRAUN K, LÖPPENBERG B, SOMMERER F, NOLDUS J, VON BODMAN C. Multiparametric Ultrasound of the Prostate: Adding Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound to Real-Time Elastography to Detect Histopathologically Confirmed Cancer. Journal of Urology. 2012;189:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAO C, NIE L, LOU C, XING D. The feasibility of using microwave-induced thermoacoustic tomography for detection and evaluation of renal calculi. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2010;55:5203–5212. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/17/020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASPERS F, CONWAY J. Measurement of Power Density in a Lossy Material by means of Electromagnetically induced acoustic signals for non-invasive determination of spatial thermal absorption in connection with pulsed hyperthermia. 12th European Microwave Conference Helsinki. 1982 [Google Scholar]

- COSTELLO LC, FRANKLIN RB. Prostatic fluid electrolyte composition for the screening of prostate cancer: a potential solution to a major problem. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:17–24. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOGRA VS, CHINNI BK, VALLURU KS, JOSEPH JV, GHAZI A, YAO JL, EVANS K, MESSING EM, RAO NA. Multispectral Photoacoustic Imaging of Prostate Cancer: Preliminary Ex-vivo Results. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:41. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.119139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EAU EAOU. Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. The role of imaging. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- EBERHARDT S, CARTER S, CASALINO D, MERRICK G, FRANK S, GOTTSCHALK A, LEYENDECKER J, NGUYEN P, OTO A, PORTER C, REMER E, ROSENTHAL S. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Prostate Cancer—Pretreatment Detection, Staging, and Surveillance. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2013;10:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECKHART A, BALMER R, SEE W, PATCH S. Ex Vivo Thermoacoustic Imaging over Large Fields of View with 108 MHz Irradiation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2011;58:2238–2246. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2128319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FALLON D, YAN L, HANSON GW, PATCH SK. RF testbed for thermoacoustic tomography. Review of Scientific Instruments. 2009;80:064301. doi: 10.1063/1.3133802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERLAY J, SOERJOMATARAM I, ERVIK M, DIKSHIT R, ESER S, MATHERS C, REBELO M, PARKIN D, FORMAN D, BRAY F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRISON T, ZEMP RJ. Coregistered photoacoustic-ultrasound imaging applied to brachytherapy. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:080502. doi: 10.1117/1.3606566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIN X, XU Y, WANG LV, FANG YR, ZANELLI CI, HOWARD SM. Imaging of high-intensity focused ultrasound-induced lesions in soft biological tissue using thermoacoustic tomography. Med Phys. 2005;32:5–11. doi: 10.1118/1.1829403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHN F. Partial Differential Equations. Springer; New York, NY: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- KAVANAGH JP. Sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, zinc, citrate and chloride content of human prostatic and seminal fluid. J Reprod Fertil. 1985;75:35–41. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0750035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAVANAGH JP, DARBY C, COSTELLO CB. The response of seven prostatic fluid components to prostatic disease. Int J Androl. 1982;5:487–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1982.tb00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUGER RA, MILLER KD, REYNOLDS HE, KISER WL, JR., REINECKE DR, KRUGER GA. Contrast enhancement of breast cancer in vivo using thermoacoustic CT at 434 MHz. Radiology. 2000;216:279–283. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.1.r00jl30279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KU G, WANG LV. Scanning microwave-induced thermoacoustic tomography: signal, resolution, and contrast. Medical Physics. 2001;28:4–10. doi: 10.1118/1.1333409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUMAR V, DWIVEDI DK, JAGANNATHAN NR. High-resolution NMR spectroscopy of human body fluids and tissues in relation to prostate cancer. NMR Biomed. 2013 doi: 10.1002/nbm.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUO N, KANG HJ, SONG DY, KANG JU, BOCTOR EM. Real-time photoacoustic imaging of prostate brachytherapy seeds using a clinical ultrasound system. J Biomed Opt. 2012;17:066005. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.066005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEDIJU BELL MA, KUO N, SONG DY, BOCTOR EM. Short-lag spatial coherence beamforming of photoacoustic images for enhanced visualization of prostate brachytherapy seeds. Biomed Opt Express. 2013;4:1964–77. doi: 10.1364/BOE.4.001964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI C, PRAMANIK M, KU G, WANG L. Image distortion in thermoacoustic tomography caused by microwave diffraction. Physical Review E. 2008;77:031923. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.031923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI M-L, ZHANG HF, MASLOV K, STOICA G, WANG LV. Improved in vivo photoacoustic microscopy based on a virtual-detector concept. Optics Letters. 2006;31:474–476. doi: 10.1364/ol.31.000474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOU C, NIE L, XU D. Effect of excitation pulse width on thermoacoustic signal characteristics and the corresponding algorithm for optimization of imaging resolution. Journal of Applied Physics. 2011;110:083101. [Google Scholar]

- LOU C, XING D. Temperature monitoring utilising thermoacoustic signals during pulsed microwave thermotherapy: a feasibility study. Int J Hyperthermia. 2010;26:338–46. doi: 10.3109/02656731003592035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOU C, YANG S, JI Z, CHEN Q, XING D. Ultrashort microwave-induced thermoacoustic imaging: a breakthrough in excitation efficiency and spatial resolution. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109:218101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.218101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOWATT G, SCOTLAND G, BOACHIE C, CRUICKSHANK M, FORD JA, FRASER C, KURBAN L, LAM TB, PADHANI AR, ROYLE J, SCHEENEN TW, TASSIE E. The diagnostic accuracy and cost-effectiveness of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and enhanced magnetic resonance imaging techniques in aiding the localisation of prostate abnormalities for biopsy: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:vii–xix. 1–281. doi: 10.3310/hta17200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOYER VA. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:120–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NARAYAN P, KURHANEWICZ J. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in prostate disease: diagnostic possibilities and future developments. The Prostate. Supplement. 1992;4:43–50. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990210507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASONI RL, EVANOFF GA, HALVERSON PG, BOWEN T. Thermoacoustic Emission by Deeply Penetrating Microwave Radiation. In: MCAVOY BR, editor. IEEE 1984 Ultrasonics Symposium. Dallas, TX.: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- NCCN, N. C. C. N. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2014a. http://www.nccn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCCN, N. C. C. N. Biopsy Technique. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2014b. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Prostate Cancer Early Detection. http://www.nccn. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIE L, XING D, YANG S. In vivo detection and imaging of low-density foreign body with microwave-induced thermoacoustic tomography. Medical Physics. 2009;36:3429–3437. doi: 10.1118/1.3157204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIE L, XING D, ZHOU Q, YANG D, GUO H. Microwave-induced thermoacoustic scanning CT for high-contrast and noninvasive breast cancer imaging. Medical Physics. 2008;35:4026–4032. doi: 10.1118/1.2966345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLSEN R, LIN J. Acoustical Imaging of a model of a Human Hand Using Pulsed Microwave Irradiation. Bioelectromagnetics. 1983;4:397–400. doi: 10.1002/bem.2250040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OUTWATER EK, MONTILLA-SOLER JL. Imaging of Prostate Carcinoma. Cancer Control. 2013;20:161–176. doi: 10.1177/107327481302000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PACHAURI D, STILES T, PURWAR N, DEY P, PATCH S. Transducer frequency response and impact on TPOAT signal. In: SPIE, editor. SPIE BIOS; San Jose: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- PARKER K, DOYLEY M, RUBENS D. Imaging the elastic properties of tissue: the 20 year perspective. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2011;56:R1–R29. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/1/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATCH S, RAO N, KELLY H, JACOBSOHN K, SEE W. Specific Heat Capacity of Freshly Excised Prostate Specimens. Physiological Measurement. 2011;32:N55–64. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/32/11/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PATTERSON M, ARSENAULT M, RILEY C, KOLIOS M, WHELAN W. Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing. SPIE; San Francisco: 2010. Optoacoustic imaging of an animal model of prostate cancer. p. 75641B. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- RAZANSKY D, KELLNBERGER S, NTZIACHRISTOS V. Near-field radiofrequency thermoacoustic tomography with impulse excitation. Medical Physics. 2010;37 doi: 10.1118/1.3467756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROGGENBUCK M, CATENACCI J, WALKER R, HANSON E, HSIEH J, PATCH S. Thermoacoustic Imaging With VHF Signal Generation – A New Contrast Mechanism for Cancer Imaging over Large Fields of View. In: EL-BAZ A, SABA L, SURI J, editors. Abdomen and Thoracic Imaging: An Engineering & Clinical Perspective. Springer; New York: 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- ROGGENBUCK M, WALKER R, CATENACCI J, PATCH S. Volumetric Thermoacoustic Imaging over Large Fields of View. Ultrasonic Imaging. 2013b;35:57–67. doi: 10.1177/0161734612471664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROOIJ MD, HAMOEN E, FÜTTERER J, BARENTSZ J, ROVERS M. Accuracy of Multiparametric MRI for Prostate Cancer Detection: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Radiology. 2014;202:343–351. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALAMI S, VIRA M, TURKBEY B, FAKHOURY M, YASKIV O, VILLANI R, BEN-LEVI E, RASTINEHAD A. Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging Outperforms the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk Calculator in Predicting Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28790. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SERKOVA NJ, GAMITO EJ, JONES RH, O'DONNELL C, BROWN JL, GREEN S, SULLIVAN H, HEDLUND T, CRAWFORD ED. The metabolites citrate, myo-inositol, and spermine are potential age-independent markers of prostate cancer in human expressed prostatic secretions. Prostate. 2008;68:620–8. doi: 10.1002/pros.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOCIETY AC. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta: 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- STAMATAKIS L, SIDDIQUI M, NIX J, LOGAN J, RAIS-BAHRAMI S, WALTON-DIAZ A, HOANG A, VOURGANTI S, TRUONG H, SHUCH B, PARNES H, TURKBEY B, CHOYKE P, WOOD B, SIMON R, PINTO P. Accuracy of Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Confirming Eligibility for Active Surveillance for Men With Prostate Cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:3359–3366. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SU JL, BOUCHARD RR, KARPIOUK AB, HAZLE JD, EMELIANOV SY. Photoacoustic imaging of prostate brachytherapy seeds. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:2243–54. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAO C, SONG T, YANG W, WU S. Ultra-wideband Microwave-Induced Thermoacoustic Tomography of Human Tissues IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium. IEEE. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- UMBEHR M, BACHMANN LM, HELD U, KESSLER TM, SULSER T, WEISHAUPT D, KURHANEWICZ J, STEURER J. Combined magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging in the diagnosis of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2009;55:575–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG LV, WU H-I. Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WANG LV, ZHAO X, SUN H, KU G. Microwave-induced acoustic imaging of biological tissues. Review of Scientific Instruments. 1999;70:3744–3748. [Google Scholar]

- WANG X, BAUER DR, WITTE R, XIN H. Microwave-induced thermoacoustic imaging model for potential breast cancer detection. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2012;59:2782–91. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2012.2210218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG X, ROBERTS W, CARSON P, WOOD D, FOWLKES B. Photoacoustic tomography: a potential new tool for prostate cancer. Biomedical Optics Express. 2010;1:1117–1126. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.001117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARLICK C. Multiparametric MRI for prostate cancer: Seeing is believing Cancer. Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/cncr.28787. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- XU M, WANG L. Pulsed-microwave-induced thermoacoustic tomography: Filtered backprojection in a circular measurement configuration. Medical Physics. 2002;29:1661–1669. doi: 10.1118/1.1493778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAN J, TAO C, WU S. Energy Transform and Initial Acoustic Pressure Distribution in Microwave-induced Thermoacoustic Tomography.. EMBS 27th Annual Conference; Shanghai, China. 2005; IEEE; 2005. pp. 1521–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZUKOTYNSKI K, HAIDER MA. Imaging in Prostate Carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2013;27:1163–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]