Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Substantial evidence shows that negative reinforcement resulting from the aversive affective consequences of opiate withdrawal may play a crucial role in drug relapse. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the loss (extinction) of conditioned aversion of drug withdrawal could facilitate the treatment of drug addiction.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Naloxone-induced conditioned place aversion (CPA) of Sprague-Dawley rats was used to measure conditioned aversion. An NMDA receptor antagonist and MAPK kinase inhibitor were applied through intracranial injections. The phosphorylation of ERK and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) was detected using Western blot.

KEY RESULTS

The extinction of CPA behaviour increased the phosphorylation of ERK and CREB in the dorsal hippocampus (DH) and basolateral amygdala (BLA), but not in the central amygdala (CeA). Intra-DH injection of AP5 or intra-BLA injection of AP-5 or U0126 before extinction training significantly attenuated ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA and impaired the extinction of CPA behaviour. Although intra-DH injections of AP-5 attenuated extinction training-induced activation of the ERK-CREB pathway in the BLA, intra-BLA injection of AP5 had no effect on extinction training-induced activation of the ERK-CREB pathway in the DH.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

These results suggest that activation of ERK and CREB in the BLA and DH is involved in the extinction of CPA behaviour and that the DH, via a direct or indirect pathway, modulates the activity of ERK and CREB in the BLA through activation of NMDA receptors after extinction training. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the extinction of conditioned aversion could facilitate the treatment of drug addiction.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed section on Opioids: New Pathways to Functional Selectivity. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2015.172.issue-2

Keywords: drug withdrawal, extinction, amygdala, hippocampal

Introduction

Opiate addiction is the chronic relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug taking (Milton and Everitt, 2012). Substantial evidence shows that negative reinforcement resulting from the aversive affective consequences of withdrawal may play a crucial role in loss of control over drug seeking (Koob, 2009; Ungless et al., 2010). Extinction therapy has been proposed as a method to reduce the motivational impact of drug-associated cues to prevent relapse (Taylor et al., 2009). However, the mechanisms underlying the extinction of conditioned aversion are not fully understood.

Extinction is a form of new learning that requires synaptic plasticity. It has been established that extinction learning and memory involves the interaction of the amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the hippocampus (Quirk and Mueller, 2008). Reciprocal anatomical projections between the mPFC, amygdala and the hippocampus appear to utilize glutamate as a primary neurotransmitter (Del Arco and Mora, 2009; Peters and De Vries, 2012). NMDA receptors (see Alexander et al., 2013) have been shown to be involved in extinction learning and memory (Myers et al., 2011). ERK is an important downstream target molecule regulated by NMDA receptors and plays an important role in synaptic plasticity (Thomas and Huganir, 2004). Its activation has been demonstrated in different brain regions with several learning paradigms (Eckel-Mahan et al., 2008; Fan et al., 2010; Lyons et al., 2013) and it is involved in activity-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity in various brain areas (Shiflett and Balleine, 2011; Zhai et al., 2013).

Conditioned place aversion (CPA) is the most sensitive measurement for the negative motivational state and can be used to explore the neurobiological mechanisms underlying the aversive memories of opioid withdrawal in opiate-dependent animals (Azar et al., 2003). Our recent study shows that extinction of CPA behaviour requires NMDA receptor-mediated activation of the ERK-CREB signalling pathway in the rat ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Wang et al., 2012). We also demonstrated that the acquisition of aversive memories requires functional interactions between the amygdala and the dorsal hippocampus (DH) (Hou et al., 2009a; b). However, it is unclear whether NMDA receptor-mediated activation of the ERK-CREB signalling pathway in the amygdala and the DH are also necessary for the extinction of CPA behaviour and whether there are functionally reciprocal modulations between the amygdala and the hippocampus in the activation of the ERK-CREB signalling pathway. Here, we address these issues using the CPA paradigm. The results from the present study demonstrated that extinction training results in the activation of ERK and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) and the DH through NMDA receptors, which are necessary for the extinction of conditioned aversion associated with morphine withdrawal and that DH modulates the activity of ERK and CREB in the BLA during extinction training through activation of NMDA receptors.

Methods

Animals

Adult Sprague-Dawley male rats (Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) weighing 220–250 g were housed three per cage under conditions of constant temperature (23 ± 2°C) and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. The total number of animals used in these studies was 195. All procedures used were as humane as possible. All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication 80-23, revised 1996). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Surgery and drug microinjection

Animals were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (55 mg·kg−1, i.p.) and the depth of anaesthesia was checked by testing for lack of a pain response to gentle pressure on the hind paws. Then, the animals were placed in the stereotaxic apparatus (Narishige, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, Japan) and were implanted with guide cannulae 2 mm above the BLA (AP, −2.9 mm; ML, ±5.0 mm; DV, −8.5 mm) or the DH (AP, −3.8 mm; ML, ±2.5 mm; DV, −2.5 mm). A stainless steel blocker was inserted into each cannula to keep them patent and prevent infection. The rats were allowed to recover from surgery for 5 days.

U0126 (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 25% DMSO and diluted in PBS to a final concentration of 200 ng·μL−1 (Li et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2012). AP-5 (10 μg·μL−1; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in PBS (Hou et al., 2009a; Myskiw et al., 2010). The rats were randomly assigned to vehicle infusion group or drug infusion group; each infusion volume was 0.5 μL per side. Bilateral microinfusions were made through 31 gauge injection cannulae (2.0 mm beyond the tip of guide cannulae) that was connected to a 10 μL microsyringe mounted in the microinfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA), and the drugs were infused over 2 min and given an additional 2 min for drug diffusion.

Histology

After behavioural testing, rats were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with saline, followed by 4% formalin. The brains were removed and stored in a 30% sucrose solution for 2–3 days. Coronal sections (30 mm thick) were cut on a cryostat (Leica, Leider Lane Buffalo Grove, IL, USA), stained with cresyl violet and then examined by light microscopy to determine the injection sites. In all experiments, animals were only kept for analyses if their cannulae were placed in the right sites.

Conditioned place aversion

Apparatus

The CPA apparatus made of Plexiglas was divided into two equal-sized compartments by a removable partition with an opening at one end, which allowed the rat free access to each compartment. The two compartments were distinguished by visual (white or black) and tactile cues (bar or slick) and provided the distinct contexts. The apparatus were equipped with an infrared photobeam connected to a computer that recorded the rat's location in the chambers.

Procedures

The experiments were performed as previously described (Hou et al., 2009b; Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, the rats were initially placed in the apparatus with the doors removed for 15 min (pre-conditioning test) to determine baseline place preference. Rats that showed a strong unconditioned aversion (<180 s in any chamber) were excluded from this study. Conditioning took place over the next 2 days. On the first day, the rats were injected with saline (1 mL·kg−1, s.c.) and then returned to home cages. Four hours later, they were again given saline and then confined to either compartment in a counterbalanced manner for 30 min. On the second day, the rats were injected with morphine (10 mg·kg−1, s.c.) and then returned to their home cages. Four hours later, they were injected with naloxone (0.3 mg·kg−1, s.c.) and then confined to the compartment opposite to that on the first day for 30 min. This compartment will be referred to as the ‘drug treatment-paired compartment’. In the post-training testing phase (24 h after the conditioning trial), all rats were allowed to freely explore the entire apparatus for 15 min. CPA score represents the time in the drug treatment-paired compartment during the testing phase minus that during the pre-conditioning phase.

Extinction

The experiments were performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, extinction training began 24 h after the post-training test and consisted of 30 min confinements in the previously naloxone-paired compartment. Three confinement days were conducted and a 15 min extinction test was performed 24 h after each confinement day.

Western blot

Most rats were decapitated under sodium pentobarbital anaesthesia 30 min after the last test. Rats in the control conditions (Ext 0 h) were decapitated at the corresponding time, but had not received extinction training. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA). Membranes were incubated in primary antibodies, including anti-pERK and anti-ERK antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-pCREB and anti-CREB (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) at a dilution of 1:2000, overnight at 4°C and in secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2.5 h at room temperature. Visualization was performed using an ECL (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Band intensities were quantified using Quantity One software from Bio-Rad. The mean of the phosphorylation level (the ratio of phosphorylated protein to total protein) of the control group was set as 100%, and the relative phosphorylation level of individual subjects was calculated relative to the mean of the control group.

Data analysis

The data were analysed with one- or two-way anova, followed by Bonferroni's post hoc tests when appropriate. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

The CPA scores induced by morphine withdrawal were significantly decreased after extinction training

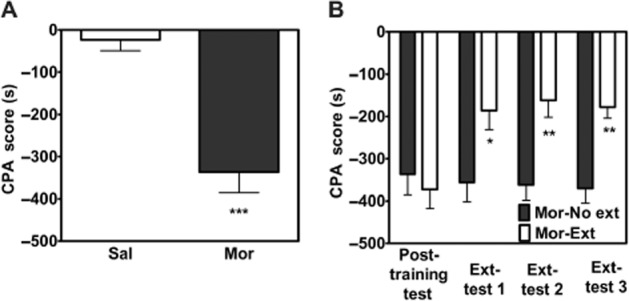

Consistent with our previous study (Hou et al., 2009b), we found that rats pretreated with a single dose of morphine, followed by one pairing with naloxone, spent significantly less time in the compartment paired with morphine withdrawal compared with rats pretreated with saline, followed by a pairing with saline (aversion score: saline/saline: −23.7 ± 75.9 s, n = 9; morphine/naloxone: −336.3 ± 49.32 s, n = 20; t = 6.35, P < 0.001; Figure 1A), indicating that naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal produced significant aversion for the environment paired with naloxone precipitation in rats exposed to a single dose of morphine. Next, the rats in the morphine group were randomly divided into two groups. The rats in the morphine-extinction group (n = 10) were repeatedly confined to the previously drug treatment-paired compartment in the absence of withdrawal, whereas the rats in the morphine-no extinction group (n = 10) were kept in their home cage. As shown in Figure 1B, after extinction training, there was a significant difference in the CPA scores between the morphine group and the morphine-extinction group. Two-way anova assays revealed the significant main effect of time (F3,54 = 3.83, P < 0.05) and extinction training (F1,54 = 9.06, P < 0.01), as well as a significant interaction between these two factors (F3,54 = 6.56, P < 0.001). The results demonstrated that naloxone-induced CPA scores in rats treated with a single dose of morphine were diminished following exposure to the previously naloxone paired environment in the absence of acute withdrawal.

Figure 1.

CPA extinction training decreased aversion scores. Rats pretreated with morphine exhibit CPA to an environment previously paired with a low dose of naloxone, whereas animals pretreated with saline do not (A). n = 10–20 per group. ***P < 0.001, t-test. The CPA scores are decreased after extinction training (B). n = 10 per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, two-way anova. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Sal, saline + saline; Mor, morphine + naloxone; Ext, extinction.

Extinction training induced activation of ERK and CREB in the BLA, but not in the central amygdala (CeA)

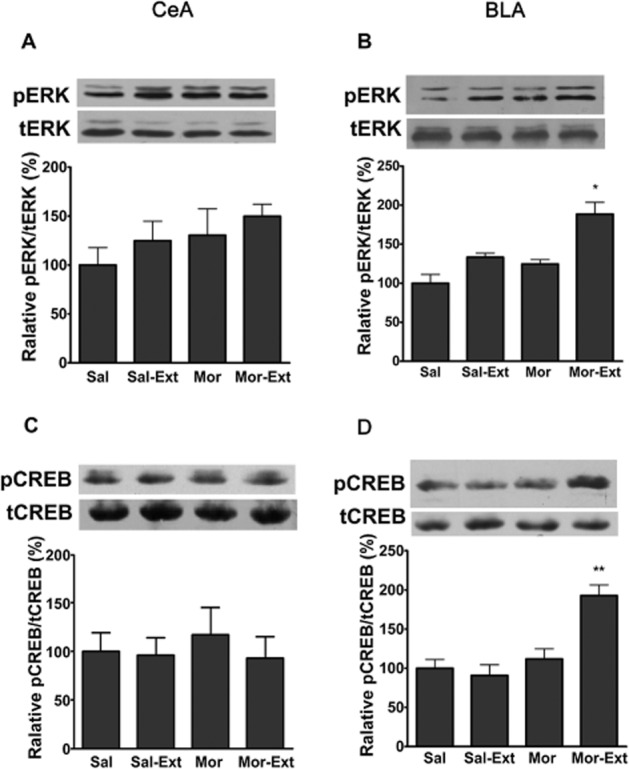

ERK activation is involved in activity-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity in various brain areas (Huang et al., 2000) and in a variety of learning paradigms, including extinction (Lu et al., 2001). Next, we determined whether ERK activation in the BLA was involved in the extinction of aversive memories associated with drug withdrawal. For this purpose, rats were randomly divided into four groups, including the CPA conditioning (saline/saline and morphine/naloxone) and extinction training (no and yes). Rats were decapitated 30 min after the last test and brains were extracted for determination of pERK in the CeA and BLA by Western blotting (n = 6–7 in each group). As shown in Figure 2A and B, increased pERK in the BLA, but not the CeA, was observed only in CPA rats that underwent extinction training. The statistical analysis included the factors of extinction training (yes and no) and CPA conditioning. One-way anova assays (F3,24 = 6.39, P < 0.01)and the following post hoc test (P < 0.05) revealed a significant effect of CPA extinction training on pERK levels in the BLA, but not the CeA.

Figure 2.

Phosphorylated ERK and CREB in the BLA, but not CeA, increased after extinction training. The level of pERK in the CeA was not changed after extinction training (A). n = 6 per group. P > 0.05, one-way anova. An increase in pERK in the BLA could be detected only in the extinction of CPA rats but not in other controls (B). n = 7 per group. *P < 0.05, one-way anova. The level of pCREB in the CeA was not changed after extinction training (C). n = 6 per group. P > 0.05, one-way anova. An increase in pCREB in the BLA could be detected only in the extinction of CPA rats but not in other controls (D). n = 6 per group. **P < 0.01, one-way anova. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Sal, saline + saline; Mor, morphine + naloxone; Ext, extinction.

The transcription factor CREB, as a target for ERK during plasticity, is perhaps the most intensively studied kinase substrate in the field of learning and memory (West et al., 2002). We subsequently assessed the effect of extinction training on pCREB activation in the CeA and the BLA. As shown in Figure 2C and D, a significant increase in pCREB in the BLA, but not in the CeA, was detected 30 min after the last test. One-way anova assays revealed a significant main effect of extinction training (morphine vs. morphine extinction: F3,20 = 13.26, P < 0.001). The following Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference between treatments for pCREB (P < 0.01, n = 6). These results suggest that activation of the ERK/CREB signalling pathway in the BLA, but not the CeA, may be involved in the extinction of CPA behaviour.

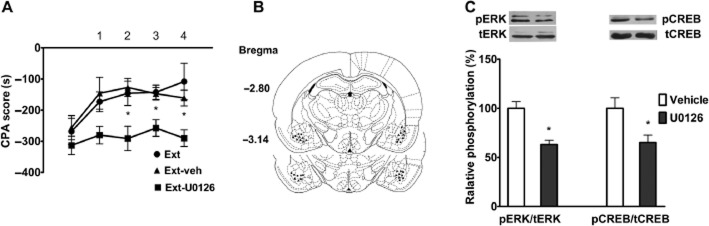

Intra-BLA injection of the MEK inhibitor U0126 suppressed extinction of CPA behaviour and activation of the ERK-CREB signalling pathway in the BLA induced by extinction training

To address the question whether ERK/CREB signalling pathway is required for the acquisition of extinction, U0126 was injected bilaterally into the BLA 20 min before extinction training. As shown in Figure 3A, intra-BLA injection of U0126 before extinction training impaired extinction of CPA behaviour. Two-way anova assays revealed the significant main effect of extinction training (F4,100 = 7.31, P < 0.01) and drug treatment (F2,100 = 15.82, P < 0.01). The following post hoc test showed a significant decrease in CPA scores in the vehicle group after extinction training (P < 0.01), but not in the U0126 group, which is significantly increased compared with the vehicle group (P < 0.05). The placement of the cannulae for the animals is shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

The ERK pathway was required for the acquisition of contextual memory extinction in the BLA. Rats infused with U0126 in the BLA before exposure to the withdrawal-paired environment showed less extinction behaviour than did vehicle-infused rats (A). n = 9–10 per group. *P < 0.05, two-way anova. Representative schematic drawing of cannulae tip positions in the BLA (▴, Ext + veh; ▪, Ext + U0126) (B). Intra-BLA injections of U0126 before extinction training suppressed extinction-induced pERK and pCREB (C). n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05, t-test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Ext, extinction; veh, vehicle.

To determine whether blockade of extinction of CPA behaviour by U0126 was induced by it preventing the activation of ERK and CREB, we examined the effects of intra-BLA injections of the same dose of U0126 on ERK and CREB phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 3C, intra-BLA injection of U0126 before extinction training attenuated extinction training-induced phosphorylation of both ERK (t = 3.24, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test) and CREB (t = 3.25, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test). These data support the idea that extinction of CPA behaviour is dependent upon the activation of ERK/CREB signalling in the BLA.

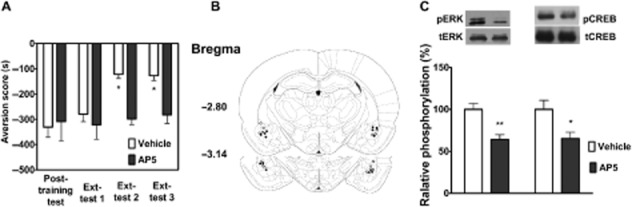

Intra-BLA injections of AP5 disrupted CPA extinction and prevented activation of ERK and CREB

Previous studies have demonstrated that NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in amygdala neurons plays a critical role in the extinction of aversion memory (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2007). Next, we determined whether the NMDA receptor in the BLA was involved in CPA extinction. As shown in Figure 4A, bilateral injection of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 into the BLA 10 min before extinction training significantly blocked the extinction of CPA behaviour. Two-way anova assays revealed a significant main effect of extinction training (F3,36 = 5.12, P < 0.01) and drug treatment (F1,36 = 5.67, P < 0.05), as well as a significant interaction between these two factors (F3,36 = 3.15, P < 0.05). The following Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant increase in CPA scores compared with the vehicle-injected control group (P < 0.05). Figure 4B illustrates the microinjection tips located in the BLA.

Figure 4.

Pre-training AP5 infusion in the BLA blocked the extinction of CPA behaviour and suppressed extinction-induced ERK and CREB phosphorylation. Intra-BLA injections of AP-5 before extinction training blocked the extinction of CPA behaviour (A). n = 7 per group. *P < 0.05, two-way anova. Schematic representation of injection sites in the BLA for rats used in the experiments (○, Vehicle; •, AP-5) (B). Intra-BLA injections of AP-5 attenuated pERK and pCREB (C). n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, t-test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Next, we assessed whether the NMDA receptor was involved in the acquisition of CPA extinction through activation of the ERK/CREB pathway in the BLA. To do this, we examined the effect of a microinjection of AP-5 into the BLA on activation of the ERK/CREB pathway. Injections of AP-5 before extinction training significantly decreased extinction-induced increases in the levels of pERK (t = 3.21, n = 6, P < 0.01, Student's t-test) and pCREB (t = 2.92, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test) (Figure 4C). These results suggest that NMDA receptor signalling in BLA is important for the extinction of CPA behaviour.

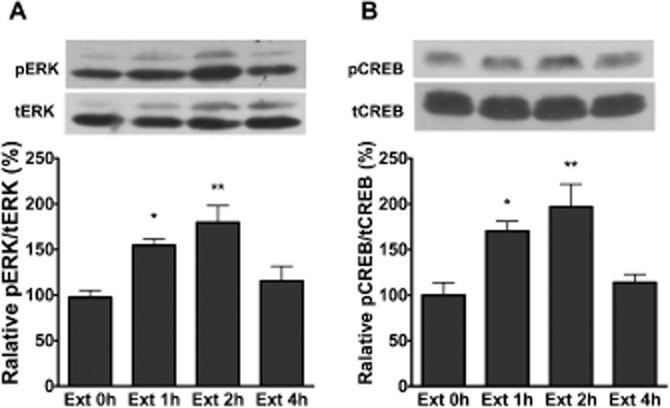

Extinction training also induced activation of ERK and CREB in the DH

Given a growing body of evidence that the hippocampus plays an important role in using contextual cues during the encoding of memory (Fischer et al., 2004), we thus investigated whether activation of the ERK/CREB pathway in the DH was involved in the extinction of CPA behaviour. For this purpose, the levels of pERK and pCREB in the DH were measured by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 5A and B, we found that pERK and pCREB levels in the DH were increased after the extinction training session. The statistical analyses included the factor of different groups and revealed a significant effect of this factor for pERK (F3,20 = 7.78, P < 0.01) and pCREB (F3,20 = 7.33, P < 0.01) in the DH. These results suggest that activation of ERK/CREB in the DH may also be involved in the extinction of CPA behaviour.

Figure 5.

CPA extinction training increased ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the DH. Extinction training induced an increase in pERK (A) and pCREB (B) in the DH. n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, one-way anova. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

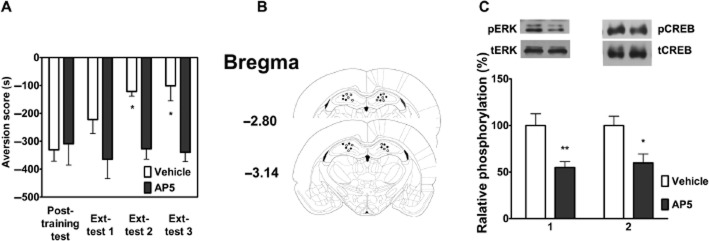

Intra-DH injections of AP-5 prevented both the extinction of CPA behaviour and activation of the ERK-CREB signalling pathway

Substantial evidence indicates that extinction depends on the glutamate NMDA receptor-linked signalling pathway, gene expression and protein synthesis in the hippocampus (Myers and Davis, 2002; Szapiro et al., 2003; Vianna et al., 2003). To determine whether NMDA receptors in the DH are involved in CPA extinction, we examined the effect of a microinjection of AP-5 into the DH on the CPA extinction. As shown in Figure 6A, bilateral injection of AP-5 into the DH 10 min before extinction training significantly blocked the extinction of CPA behaviour. Two-way anova assays revealed a significant main effect of extinction training (F3,36 = 3.25, P < 0.05) and drug treatment (F1,36 = 7.11, P < 0.05), as well as a significant interaction between these two factors (F3,36 = 4.36, P < 0.05). The following Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant increase in CPA scores compared with the vehicle-injected control group (P < 0.05). Figure 6B illustrates the microinjection tips located in the DH.

Figure 6.

Effects of intra-DH injection of AP-5 on the ERK/CREB pathway in the DH and the extinction of CPA behaviour. Intra-DH injections of AP-5 before extinction training blocked the extinction of CPA behaviour (A). n = 7 per group. *P < 0.05, two-way anova. Schematic representation of injection sites in the DH for rats used in the experiments (○, Vehicle; •, AP-5) (B). Intra-DH injections of AP-5 attenuated pERK and pCREB (C). n = 6 per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01, t-test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Next, we assessed whether NMDA receptors were involved in the acquisition of CPA extinction through activation of the ERK/CREB pathway in the DH, by examining the effects of microinjection of AP-5 into the DH on activation of the ERK/CREB pathway. As shown in Figure 6C, intra-DH injections of AP-5 before extinction training significantly decreased extinction-induced increases in the levels of pERK (t = 4.26, n = 6, P < 0.01, Student's t-test) and pCREB (t = 2.82, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test). These results support the notion that the glutamatergic system within the DH participates in the extinction of CPA behaviour.

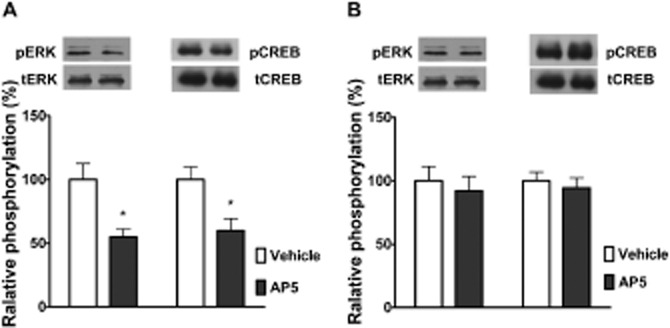

Intra-DH injections of AP-5 attenuated extinction training-induced activation of the ERK-CREB pathway in the BLA, whereas intra-BLA injection of AP5 had no effect on extinction training-induced activation of the ERK-CREB pathway in the DH

Many studies suggest that the influence of the glutamatergic system within the DH on amygdala plasticity has a critical role in spatial and contextual learning (Akirav and Richter-Levin, 2002). Moreover, considerable evidence has shown that the amygdala is functionally and anatomically connected to the hippocampus (McIntyre et al., 2005; Huff et al., 2006; Hou et al., 2009b). We hypothesized that the DH might exert a regulatory effect on synaptic plasticity in the BLA. To test this, we examined the effect of intra-DH injections of AP-5 on the phosphorylation of ERK and CREB. As shown in Figure 7A, intra-DH injections of AP-5 before extinction training significantly decreased extinction-induced increases in the levels of pERK (t = 2.87, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test) and pCREB (t = 2.34, n = 6, P < 0.05, Student's t-test) in the BLA.

Figure 7.

The DH regulates ERK/CREB activation in the BLA associated with the extinction of CPA behaviour. Intra-DH injection of AP-5 before extinction training prevented the activation of ERK and CREB in the BLA induced by extinction training (A). Intra-BLA injections of AP-5 had no effect on the level of pERK and pCREB in the DH (B); n = 6 per group, P > 0.05, t-test. (A) *P < 0.05, t-test; n = 6 per group. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Next, we also assessed the effects of microinjection of AP-5 into the BLA on extinction-induced increases in pERK and pCREB in the DH. As shown in Figure 7B, intra-BLA injections of AP-5 before extinction training failed to attenuate extinction-induced increases in the levels of pERK (t = 0.87, n = 6, P > 0.05, Student's t-test) and pCREB (t = 0.47, n = 6, P > 0.05, Student's t-test) in the DH. These results support the notion that the glutamatergic system within the DH can modulate activation of the ERK/CREB pathway in the BLA, and this contributes to the extinction of CPA behaviour.

Discussion

The two main findings of this study are that: (i) extinction of CPA behaviour induces an increase in NMDA receptor-dependent ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA, but not in the CeA, as intra-BLA injection of AP-5 or U0126 before extinction training significantly attenuated ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA and impaired the extinction of CPA behaviour. (ii) NMDA receptor signalling in the DH can modulate ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA via a direct or indirect pathway, because intra-DH injection of AP-5 before extinction training significantly attenuated ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA, whereas intra-BLA injection of AP-5 failed to diminish activation of ERK and CREB in the DH. Thus, our results demonstrate that interactions occurring in the DH and the BLA are essential for the extinction of conditioned aversion of drug withdrawal, and reveal a role for the direct or indirect neural circuit between the DH and BLA in regulating the extinction of CPA behaviour.

The amygdala is one of the key brain structures for emotional memory acquisition and storage (LeDoux, 2000). The amygdala is composed of several distinct nuclei, including the basolateral complex of the amygdala and the central nucleus. It is well established that glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in the BLA is crucial for extinguishing conditioned fear (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2007; Zimmerman and Maren, 2010). Substantial evidence demonstrates that local interference with glutamatergic synaptic plasticity in the BLA, such as infusion of NMDA receptor antagonists or ERK/MAPK inhibitor into the BLA, prevents or attenuates extinction (Lu et al., 2001; Herry et al., 2006; Zimmerman and Maren, 2010). Likewise, the present study demonstrated that extinction of CPA behaviour results in the activation of ERK and CREB in the BLA and that intra-BLA injection of AP-5 or U0126 before extinction training suppressed the activation of ERK and CREB induced by extinction training and impaired the extinction of CPA behaviour. Our findings support an important role for NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity in the BLA in extinction learning.

Intriguingly, the present study also demonstrated that NMDA receptor-dependent activation of ERK and CREB only occurs in the BLA, but not in the CeA, in response to extinction training. Consistent with our findings, a recent study showed that infusion of AP-5 into the CeA does not impair extinction of conditioned fear (Zimmerman and Maren, 2010). Our results, together with the results from Zimmerman and Maren (2010), suggest that NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity in the CeA may not be required for extinction learning, although there is evidence that NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity in the CeA is involved in the acquisition of conditioned fear (Wilensky et al., 2006). The functional dissociation between the BLA and the CeA has also been reported by several previous studies (Bahar et al., 2003; Goosens and Maren, 2003; Zimmerman and Maren, 2010).

In addition to the BLA, there is substantial evidence to support an important role for the DH in contextual fear conditioning (Phillips and LeDoux, 1992; Anagnostaras et al., 2001; Matus-Amat et al., 2004). Also, it is increasingly recognized that the DH contributes to the extinction of contextual freezing (Chen et al., 2005; Corcoran et al., 2005). Furthermore, up-regulation of ERK activity in the DH is required for the extinction of contextual fear (Fischer et al., 2007; Tronson et al., 2008). In line with these findings, in the present study it was demonstrated that training for extinction of CPA behaviour enhances ERK and CREB phosphorylation in the DH, and intra-DH injection of AP-5 impairs the extinction of CPA behaviour, supporting the crucial role of the DH in extinction learning. More importantly, we found that intra-DH injection of AP-5 before extinction training also significantly attenuated the activation of ERK and CREB in the BLA.

There is considerable evidence that the amygdala and hippocampus are anatomically connected to each other (Pitkanen et al., 2000) and functionally interact during encoding of emotional memory (Richardson et al., 2004; Calandreau et al., 2006). It has been shown that intra-DH infusion of muscarinic antagonists or NMDA receptor antagonists diminishes contextual fear conditioning-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 or CREB in the BLA (Calandreau et al., 2006; de Oliveira Coelho et al., 2013). It has also been shown that a lesion in the DH disrupts the context specificity of extinction and impairs the context dependence of amygdala neuronal activity evoked by an extinguished conditioned stimulus (Ji and Maren, 2005). Consistent with these findings, in the present study it was shown that training for extinction of CPA behaviour increases both the ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation in the DH and the BLA and that intra-DH infusion of AP5 before extinction training prevents ERK1/2 and CREB phosphorylation in the BLA and impairs the extinction of CPA behaviour. These results indicate that the DH can modulate the extinction of CPA behaviour by directly or indirectly influencing learning-related plasticity in the BLA and support a role for the direct or indirect neural circuit between the DH and the BLA in regulating the contextual control of extinction.

In a previous study we demonstrated that lesions of the amygdala abolishe synaptic actin rearrangements in the DH induced by place aversion conditioning and impair CPA formation, which suggests that the amygdala may control synaptic plasticity in the DH during the acquisition of aversive memory (Hou et al., 2009a; b). In addition, a large amount of data support the idea that the amygdala exerts a modulatory influence on hippocampal functions during fear conditioning (Kim et al., 2005; McIntyre et al., 2005; Huff et al., 2006). Specifically, the BLA is likely to be the principal region that modulates hippocampal consolidation processes. Taken together, these data suggest a dynamic interaction occurs between the amygdala and hippocampus, in which both regions mutually influence the plasticity processes.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that interactions between the DH and the BLA, through mechanisms involving the NMDA receptor-mediated ERK-CREB signalling pathway, are necessary for the extinction of CPA behaviour and suggest a similarity between neural mechanisms mediating extinction of conditioning to interoceptive (and presumably affective) withdrawal cues and mechanisms underlying the extinction of conditioned fear to nociceptive cues (usually footshock). The present findings provide further evidence for a critical role of NMDA receptor-mediated plasticity, via the ERK/CREB pathway in the BLA and DH, in the extinction of negative affective memories.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants 2013CB835100, 2009CB522005, 2012ZX09301001-005 and 2012BAI01B00 (to J-G. L.) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China and by grants 81130087 and 91232716 (to J-G. L.) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and by grant 13JC140680 (to J-G. L.) from the Committee of Science and Technology of Shanghai.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CeA

central amygdala

- CPA

conditioned place aversion

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding protein

- DH

dorsal hippocampus

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Akirav I, Richter-Levin G. Mechanisms of amygdala modulation of hippocampal plasticity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9912–9921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09912.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH. Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ CGTP Collaborators. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: Ligand gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras SG, Gale GD, Fanselow MS. Hippocampus and contextual fear conditioning: recent controversies and advances. Hippocampus. 2001;11:8–17. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2001)11:1<8::AID-HIPO1015>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar MR, Jones BC, Schulteis G. Conditioned place aversion is a highly sensitive index of acute opioid dependence and withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;170:42–50. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1514-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar A, Samuel A, Hazvi S, Dudai Y. The amygdalar circuit that acquires taste aversion memory differs from the circuit that extinguishes it. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1527–1530. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calandreau L, Trifilieff P, Mons N, Costes L, Marien M, Marighetto A, et al. Extracellular hippocampal acetylcholine level controls amygdala function and promotes adaptive conditioned emotional response. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13556–13566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3713-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Garelick MG, Wang H, Lil V, Athos J, Storm DR. PI3 kinase signaling is required for retrieval and extinction of contextual memory. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:925–931. doi: 10.1038/nn1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran KA, Desmond TJ, Frey KA, Maren S. Hippocampal inactivation disrupts the acquisition and contextual encoding of fear extinction. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8978–8987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2246-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Arco A, Mora F. Neurotransmitters and prefrontal cortex-limbic system interactions: implications for plasticity and psychiatric disorders. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:941–952. doi: 10.1007/s00702-009-0243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan KL, Phan T, Han S, Wang H, Chan GC, Scheiner ZS, et al. Circadian oscillation of hippocampal MAPK activity and cAmp: implications for memory persistence. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1074–1082. doi: 10.1038/nn.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Zhao Z, Orr PT, Chambers CH, Lewis MC, Frick KM. Estradiol-induced object memory consolidation in middle-aged female mice requires dorsal hippocampal extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4390–4400. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4333-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Schrick C, Spiess J, Radulovic J. Distinct roles of hippocampal de novo protein synthesis and actin rearrangement in extinction of contextual fear. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1962–1966. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5112-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A, Radulovic M, Schrick C, Sananbenesi F, Godovac-Zimmermann J, Radulovic J. Hippocampal Mek/Erk signaling mediates extinction of contextual freezing behavior. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goosens KA, Maren S. Pretraining NMDA receptor blockade in the basolateral complex, but not the central nucleus, of the amygdala prevents savings of conditional fear. Behav Neurosci. 2003;117:738–750. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.117.4.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, Trifilieff P, Micheau J, Luthi A, Mons N. Extinction of auditory fear conditioning requires MAPK/ERK activation in the basolateral amygdala. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YY, Liu Y, Kang S, Yu C, Chi ZQ, Liu JG. Glutamate receptors in the dorsal hippocampus mediate the acquisition, but not the expression, of conditioned place aversion induced by acute morphine withdrawal in rats. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2009a;30:1385–1391. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou YY, Lu B, Li M, Liu Y, Chen J, Chi ZQ, et al. Involvement of actin rearrangements within the amygdala and the dorsal hippocampus in aversive memories of drug withdrawal in acute morphine-dependent rats. J Neurosci. 2009b;29:12244–12254. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1970-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Martin KC, Kandel ER. Both protein kinase A and mitogen-activated protein kinase are required in the amygdala for the macromolecular synthesis-dependent late phase of long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6317–6325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06317.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huff NC, Frank M, Wright-Hardesty K, Sprunger D, Matus-Amat P, Higgins E, et al. Amygdala regulation of immediate-early gene expression in the hippocampus induced by contextual fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1616–1623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4964-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Maren S. Electrolytic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus disrupt renewal of conditional fear after extinction. Learn Mem. 2005;12:270–276. doi: 10.1101/lm.91705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Koo JW, Lee HJ, Han JS. Amygdalar inactivation blocks stress-induced impairments in hippocampal long-term potentiation and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1532–1539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4623-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl. 1):18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux JE. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:155–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Li FQ, Wang XY, Wu P, Zhao M, Xu CM, et al. Central amygdala extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathway is critical to incubation of opiate craving. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13248–13257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3027-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu KT, Walker DL, Davis M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in the basolateral nucleus of amygdala is involved in extinction of fear-potentiated startle. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-j0005.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons D, de Jaeger X, Rosen LG, Ahmad T, Lauzon NM, Zunder J, et al. Opiate exposure and withdrawal induces a molecular memory switch in the basolateral amygdala between ERK1/2 and CaMKIIα-dependent signaling substrates. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14693–14704. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1226-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus-Amat P, Higgins EA, Barrientos RM, Rudy JW. The role of the dorsal hippocampus in the acquisition and retrieval of context memory representations. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2431–2439. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1598-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre CK, Miyashita T, Setlow B, Marjon KD, Steward O, Guzowski JF, et al. Memory-influencing intra-basolateral amygdala drug infusions modulate expression of Arc protein in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10718–10723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504436102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton AL, Everitt BJ. The persistence of maladaptive memory: addiction, drug memories and anti-relapse treatments. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1119–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Behavioral and neural analysis of extinction. Neuron. 2002;36:567–584. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Carlezon WA, Jr, Davis M. Glutamate receptors in extinction and extinction-based therapies for psychiatric illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:274–293. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myskiw JC, Fiorenza NG, Izquierdo LA, Izquierdo I. Molecular mechanisms in hippocampus and basolateral amygdala but not in parietal or cingulate cortex are involved in extinction of one-trial avoidance learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Coelho CA, Ferreira TL, Soares JC, Oliveira MG. Hippocampal NMDA receptor blockade impairs CREB phosphorylation in amygdala after contextual fear conditioning. Hippocampus. 2013;23:545–551. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, De Vries TJ. Glutamate mechanisms underlying opiate memories. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a012088. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Pikkarainen M, Nurminen N, Ylinen A. Reciprocal connections between the amygdala and the hippocampal formation, perirhinal cortex, and postrhinal cortex in rat. A review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;911:369–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Mueller D. Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:56–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson MP, Strange BA, Dolan RJ. Encoding of emotional memories depends on amygdala and hippocampus and their interactions. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:278–285. doi: 10.1038/nn1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiflett MW, Balleine BW. Contributions of ERK signaling in the striatum to instrumental learning and performance. Behav Brain Res. 2011;218:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, Bush DE, LeDoux JE. Acquisition of fear extinction requires activation of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in the lateral amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1929–1940. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapiro G, Vianna MR, McGaugh JL, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. The role of NMDA glutamate receptors, PKA, MAPK, and CAMKII in the hippocampus in extinction of conditioned fear. Hippocampus. 2003;13:53–58. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JR, Olausson P, Quinn JJ, Torregrossa MM. Targeting extinction and reconsolidation mechanisms to combat the impact of drug cues on addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl. 1):186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronson NC, Schrick C, Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Pages G, Pouyssegur J, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of fear extinction and depression-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1570–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Argilli E, Bonci A. Effects of stress and aversion on dopamine neurons: implications for addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vianna MR, Igaz LM, Coitinho AS, Medina JH, Izquierdo I. Memory extinction requires gene expression in rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;79:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7427(03)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WS, Kang S, Liu WT, Li M, Liu Y, Yu C, et al. Extinction of aversive memories associated with morphine withdrawal requires ERK-mediated epigenetic regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor transcription in the rat ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13763–13775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. Regulation of transcription factors by neuronal activity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:921–931. doi: 10.1038/nrn987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky AE, Schafe GE, Kristensen MP, LeDoux JE. Rethinking the fear circuit: the central nucleus of the amygdala is required for the acquisition, consolidation, and expression of Pavlovian fear conditioning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12387–12396. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4316-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai S, Ark ED, Parra-Bueno P, Yasuda R. Long-distance integration of nuclear ERK signaling triggered by activation of a few dendritic spines. Science. 2013;342:1107–1111. doi: 10.1126/science.1245622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman JM, Maren S. NMDA receptor antagonism in the basolateral but not central amygdala blocks the extinction of Pavlovian fear conditioning in rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1664–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]