Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Tolerance to the behavioural effects of morphine is blunted in β-arrestin-2 knockout mice, but opioid withdrawal is largely unaffected. The cellular mechanisms of tolerance have been studied in some neurons from β-arrestin-2 knockouts, but tolerance and withdrawal mechanisms have not been examined at the cellular level in periaqueductal grey (PAG) neurons, which are crucial for central tolerance and withdrawal phenomena.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

μ-Opioid receptor (MOPr) inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channel currents (ICa) was examined by patch-clamp recordings from acutely dissociated PAG neurons from wild-type and β-arrestin-2 knockout mice treated chronically with morphine (CMT) or vehicle. Opioid withdrawal-induced activation of GABA transporter type 1 (GAT-1) currents was determined using perforated patch recordings from PAG neurons in brain slices.

KEY RESULTS

MOPr inhibition of ICa in PAG neurons was unaffected by β-arrestin-2 deletion. CMT impaired coupling of MOPrs to ICa in PAG neurons from wild-type mice, but this cellular tolerance was not observed in neurons from CMT β-arrestin-2 knockouts. However, β-arrestin-2 knockouts displayed similar opioid-withdrawal-induced activation of GAT-1 currents as wild-type PAG neurons.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In β-arrestin-2 knockout mice, the central neurons involved in the anti-nociceptive actions of opioids also fail to develop cellular tolerance to opioids following chronic morphine. The results also provide the first cellular physiological evidence that opioid withdrawal is not disrupted by β-arrestin-2 deletion. However, the unaffected basal sensitivity to opioids in PAG neurons provides further evidence that changes in basal MOPr sensitivity cannot account for the enhanced acute nociceptive response to morphine reported in β-arrestin-2 knockouts.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed section on Opioids: New Pathways to Functional Selectivity. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2015.172.issue-2

Keywords: arrestins, morphine, μ-opioid receptor, opioid tolerance, opioid withdrawal, periaqueductal grey

Introduction

Chronic morphine administration leads both to alterations in μ-opioid receptor (MOPs; Alexander et al., 2013, Cox et al., 2015) signalling and the development of complex adaptations in the neuronal circuitry involved in the characteristic responses to opioids to produce opioid tolerance, dependence and withdrawal (Williams et al., 2001; Christie, 2008). However, it is unclear whether common molecular mechanisms are involved in both tolerance and dependence. β-Arrestin-2 (βarr-2, arrestin3) is a multifunctional protein that participates in GPCR signalling and is involved in the rapid attenuation of GPCR signalling and mechanisms of opioid tolerance (Williams et al., 2013). It has been reported that mice lacking βarr-2 have an exaggerated acute antinociceptive response to morphine and display reduced tolerance to these antinociceptive effects (Bohn et al., 1999; 2000; 2002; Raehal et al., 2011). βarr-2 knockout mice display an unchanged (Bohn et al., 2000) or slightly reduced sensitivity (Raehal and Bohn, 2011) to naloxone-precipitated withdrawal after chronic morphine treatment (CMT). Physiological and biochemical studies of MOPr sensitivity in untreated βarr-2 knockout mice have yielded conflicting results. Studies using guanosine 5-3-O-(thio)triphosphate (GTPγS) assays have generally reported enhanced basal MOPr sensitivity in βarr-2 knockouts (Bohn et al., 1999; 2000; 2002), but electrophysiological studies have found reduced sensitivity (Walwyn et al., 2007; Dang et al., 2009; 2011). Consistent with behavioural studies, electrophysiological studies have confirmed blunted cellular tolerance in locus coeruleus neurons from βarr-2 knockout mice, but whether these neurons are involved in analgesic tolerance is unclear (Dang et al., 2011).

The midbrain periaqueductal grey (PAG) mediates important aspects of opioid anti-nociception, tolerance and withdrawal, although adaptations to CMT are diverse and not restricted to this region (Williams et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2006; Christie, 2008). We have previously described a series of cellular adaptations in the PAG following CMT with a sustained release morphine preparation. These include enhanced release of GABA driven by increased activity of the GABA transporter type 1 (GAT-1) (Bagley et al., 2005b; 2011), a switch in the mechanism by which μ-opioids inhibit GABA release in the PAG (Ingram et al., 1998; Hack et al., 2003) and a decrease in the efficacy of μ-opioids to inhibit voltage-gated calcium channel currents (ICa; Bagley et al., 2005a). We have shown that increased GAT-1 activity in the PAG is largely responsible for centrally mediated opioid withdrawal behaviours (Bagley et al., 2011). The role of other adaptations in withdrawal is less clear. In this study, we examined whether the presence of βarr-2 was important for chronic morphine-induced changes to MOPr coupling and GAT-1 activity. We found that untreated mice lacking βarr-2 respond to morphine indistinguishably from wild-type animals, and that while changes in GAT-1 activity are maintained in βarr-2 knockout animals, the reduced inhibition of ICa seen in chronic morphine-treated wild-type mice is not seen in βarr-2 knockout animals. Thus, cellular tolerance is abolished, but an important cellular adaptation responsible for opioid withdrawal, opioid modulation of the enhanced GAT-1 transporter current, is maintained.

Methods

All experiments were performed on male mice (n = 40) according to protocols approved by the RNSH Animal Ethics Committee, which complies with the National Health and Medical Research Council Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. All experiments were performed on routinely genotyped, 4–8 weeks old βarr-2 knockout mice and wild-type controls on a C57Bl6 background provided by Drs Lefkowitz and Caron (Duke University, see Bohn et al., 2000). We maintained the colony as heterozygote –x-heterozygote crosses for at least eight generations prior to commencement of this study. βarr-2 knockout and wild-type animals used in the present study were genotyped offspring from these multiple heterozygote –x-heterozygote crosses. Mice were kept in 12 h day–night cycle in a low background noise room ventilated at constant temperature of 21–22°C. Animals were housed in groups of up to six with environmental enrichment. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Chronic morphine treatment

CMT was performed as previously described (Bagley et al., 2005a; b). Briefly, mice were administered a series of three s.c. injections of morphine base (300 mg·kg−1) in a sustained release emulsion on alternate days over a 5 day period. The sustained release preparation consisted of 50 mg of morphine base suspended in 1 mL of emulsion [0.1 mL of Arlacel A (mannide monooleate), 0.4 mL of light liquid paraffin and 0.5 mL of 0.9% (w v−1) NaCl]. Injections of warmed suspension were made under light isoflurane (4% in air) anaesthesia. Vehicle mice were injected with suspension lacking morphine. Vehicle and morphine treatments were performed in parallel. Animals were used on day 6 or day 7.

Tissue preparation

Mice (at least 6 weeks old for dissociated cells, 4–6 weeks old for slice recordings) were anaesthetized with isoflurane and killed by decapitation. Coronal midbrain slices (220–250 μm thick for slice recording, 350 μm thick for dissociation) containing the PAG were cut with a vibratome in ice-cold physiological saline [artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF)] of composition (mM) NaCl 126, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2.4, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 24 and glucose 11; gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2 and stored for 30 min at 35oC. Cells were dissociated as previously described (Connor et al., 1999b). Briefly, slices were transferred to a dissociation buffer of composition (mM) Na2SO4 82, K2SO4 30, HEPES 10, MgCl2 5, glucose 10, containing 20 u·mL−1 papain (pH 7.3) and incubated for 2 min at 35°C. The slices were then placed in fresh dissociation buffer containing 1 mg·mL−1 BSA and 1 mg·mL−1 trypsin inhibitor and the PAG region was sub-dissected from each slice with a fine tungsten wire. Cells were dissociated from the slices by gentle trituration, plated onto plastic culture dishes and kept at room temperature in dissociation buffer. Buffers for cell dissociation did not contain morphine, so isolated cells were in a withdrawn state for the duration of the experiments.

Brain slice electrophysiology

After being cut, PAG slices were maintained at 34°C in a submerged chamber containing ACSF and were later transferred to a chamber superfused at 2 mL·min−1 with ACSF (34°C) for recording. Brain slices from both morphine-dependent and vehicle-treated mice were maintained in vitro in ACSF containing 5 μM morphine. Slices were spontaneously withdrawn by incubation in morphine-free ACSF for at least 1 h before an experiment. PAG neurons were visualized using infrared Nomarski optics and recordings were made from neurons in the ventrolateral region of the PAG (Bagley et al., 2005b). Perforated patch-clamp recordings were made using electrodes (4–5 MΩ) filled with (mM) K acetate 120; HEPES 40; EGTA 10; MgCl2 5; with Pluronic F-127 0.25 mg·mL−1; amphotericin B 0.12 mg·mL−1 (pH 7.2, 290 mOsmol·L−1). A liquid junction potential for K acetate internal solution of −8 mV was corrected. Series resistance (<25 MΩ) was compensated by 80% and continuously monitored. During perforated patch recordings, currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City CA, USA), digitized, filtered (at 2 kHz) and then acquired (sampling at 10 kHz) in pClamp (Axon Instruments) or using Axograph Acquisition software (Axon Instruments). Drugs were added directly to the ACSF and applied by switching the bath superfusion to the ACSF containing the drugs.

Dissociated PAG neuron electrophysiology

Recordings of currents through Ca2+ channels (ICa) were made using standard whole-cell patch-clamp techniques (Hamill et al., 1981) at room temperature (20–24°C), as previously described (Connor et al., 1999b). Dishes of cells were superfused with a HBS of composition (mM): NaCl 140, KCl 2.5, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1.2, HEPES 10 and glucose 10 (pH 7.3). For ICa recordings, cells were perfused with solution containing (mM) tetraethylammonium chloride 140, BaCl2 4, CsCl 2.5, HEPES 10, glucose 10 and BSA 0.05% (pH 7.3). Recordings were made with fire-polished borosilicate pipettes of 2–4 MΩ resistance when filled with intracellular solution comprising (mM) CsCl 120, MgATP 5, NaCl 5, Na2GTP 0.2, EGTA 10, CaCl2 2 and HEPES 10 (pH 7.3). The peak ICa in each cell was determined by stepping the membrane potential from a holding potential of −90 mV to potentials between −60 and + 60 mV, in 10 mV increments. Cells were repetitively stepped to 0 mV and drugs were applied via an array of sewer pipes positioned about 200 μm from the cell. Neurons in which ICa declined in the absence of drug treatment were discarded. The inhibition by drugs was quantified by measuring the current amplitude isochronically with the peak of the control ICa. Whole-cell capacitance and series resistance were compensated manually by nulling the capacitive transient evoked by a 20 mV pulse from −90 mV. Series resistance compensation of at least 80% was used in all experiments. An approximate value of whole cell capacitance was read from the amplifier capacitance compensation circuit (Axopatch 1D; Axon Instruments). Leak current was subtracted on line using a P/8 protocol. Cells with an initial holding current of >20 pA at −90 mV were discarded; most cells had holding currents at −90 mV of <5 pA. Evoked ICa were filtered at 2 kHz, sampled at 5–10 kHz and recorded on hard disk for later analysis. Data were collected and analysed offline with the PCLAMP (version 5) and Axograph (version 4) suite of programs (Axon Instruments). Recordings were made between 30 min and up to 6 h after dissociation. ICa amplitude was similar in cells recorded first (191 ± 14 pA·pF−1) and last (184 ± 12 pA, P = 0.74, n = 33 each) on any day.

Statistical analysis

Concentration–response data from different days were pooled and data from each condition were compared with a two-way anova. Where there was a significant variation produced by treatment, the responses at each concentration were compared using a Bonferroni post hoc test corrected for multiple comparisons. The proportion of DAMGO (Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-N-Me-Phe-Gly-ol enkephalin)-responding cells in each group of cells was compared using a chi-squared test. Other comparisons were made using Student's unpaired t-test. Statistical tests were performed in Graphpad Prism (http://www.graphpad.com).

Drugs and chemicals

Buffer salts were from BDH Australia or Sigma Australia. Papain was from Worthington Biochemical Corporation (Freehold, NJ, USA). All other chemicals were from Sigma Australia, except the following: Met-enkephalin and DAMGO were from Auspep (Melbourne, Australia). Baclofen was from Research Biochemicals International (Natick, MA, USA). CNQX was from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). Tetrodotoxin was from Alomone (Jerusalem, Israel). Morphine base and morphine hydrochloride were from GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, Middlesex, UK). CGP55845 was a gift from Ciba Ltd (Basel, Switzerland).

Results

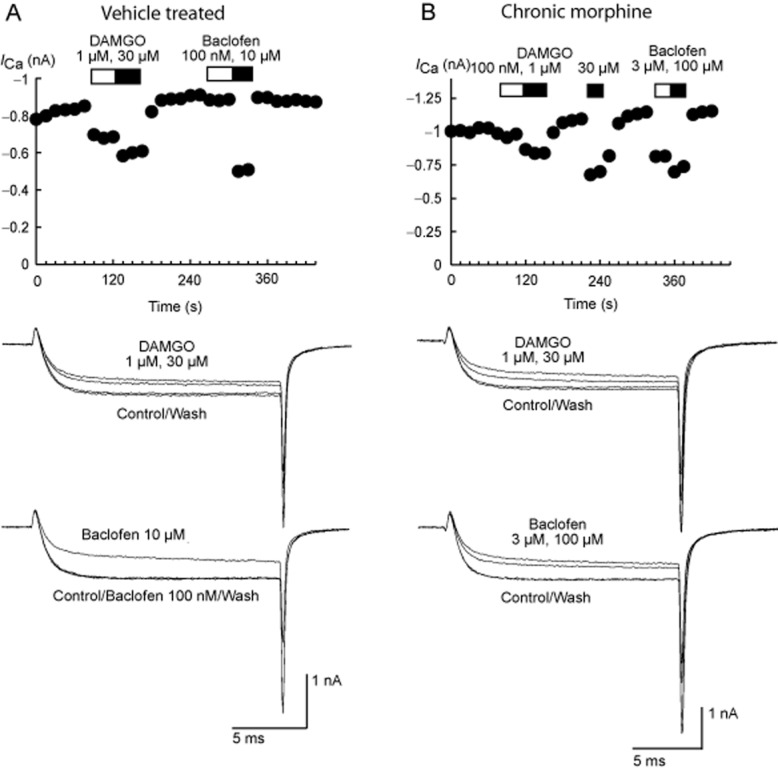

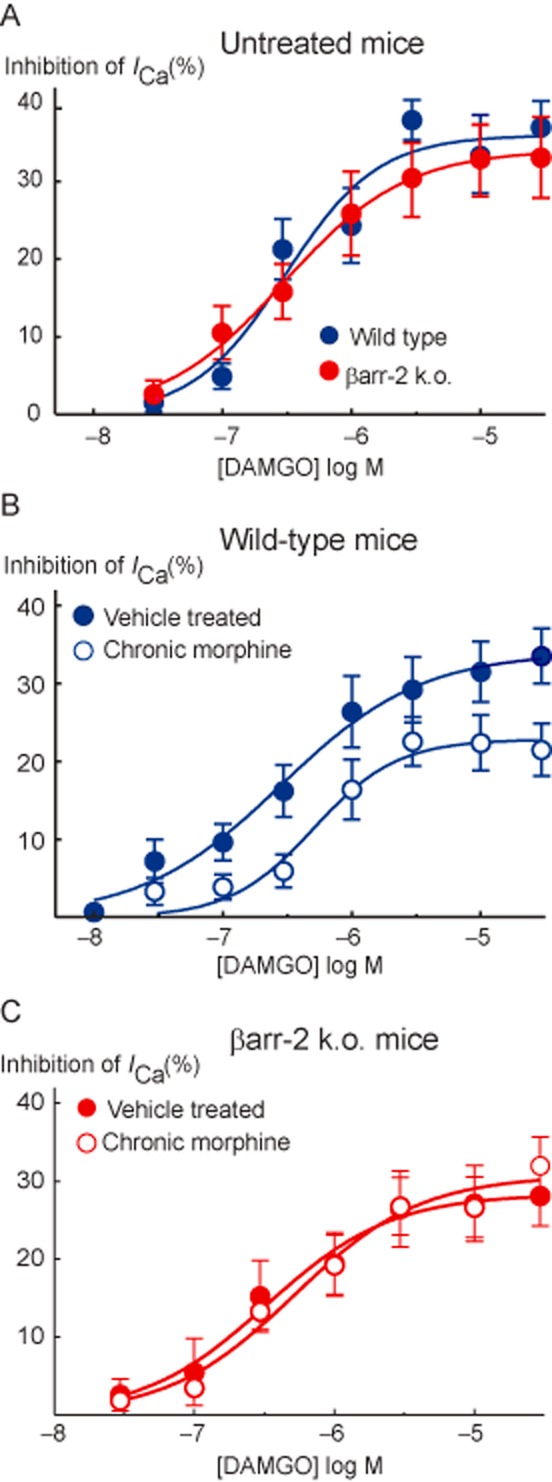

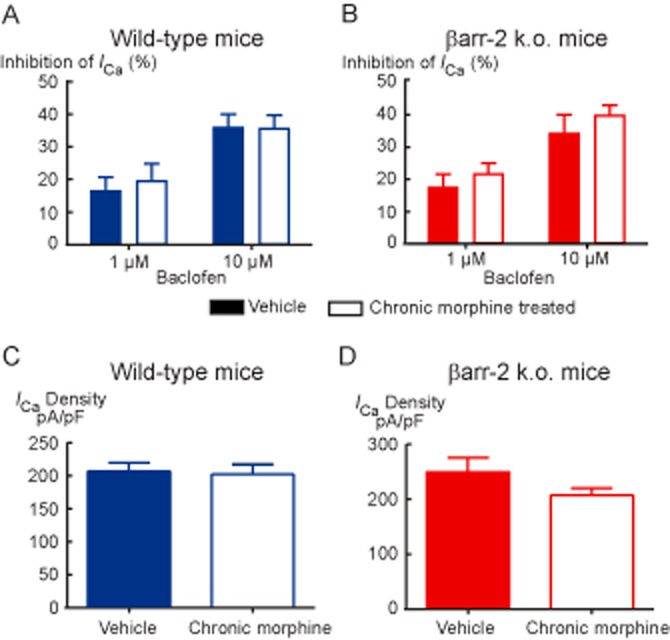

The μ-opioid agonist DAMGO rapidly and reversibly inhibits ICa in most mouse PAG neurons; examples of this inhibition in neurons from vehicle-treated and chronic morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout mice are shown in Figure 1. There was no difference in the potency or efficacy of the μ-opioid agonist DAMGO to inhibit ICa in PAG neurons between untreated wild-type and βarr-2 knockout mice [Figure 2A; two-way anova comparing DAMGO inhibition in cells from naïve animals of either genotype showed a significant interaction for concentration (P < 0.001), but no significant interaction for genotype (P = 0.60)]. DAMGO inhibited ICa in cells from wild-type mice with an EC50 of 310 nM (pEC50 6.51 ± 0.15), and maximum inhibition of 36 ± 3%, in cells from βarr-2 knockout animals, the EC50 was 300 nM (pEC50 6.52 ± 0.05), the maximum inhibition was 34 ± 1%. We previously reported that CMT produces a decrease in the effectiveness of μ-opioids to inhibit ICa in mouse PAG neurons (Bagley et al., 2005a) and these effects were reproduced in the βarr-2 wild-type mice [Figure 2B; two-way anova comparing DAMGO inhibition in cells from wild-type vehicle and CMT animals showed a significant interaction for concentration (P < 0.001), and treatment (P < 0.001)]. As previously reported (Bagley et al., 2005a), the MOPr agonist DAMGO was also less effective at inhibiting ICa in PAG neurons from chronic morphine-treated wild-type (wt) mice than in neurons from vehicle-treated animals, with the maximum inhibition of ICa reduced from 34 ± 2% in cells from vehicle-treated mice to 23 ± 2% in chronic morphine-treated cells [P = 0.009, Bonferroni post hoc test corrected for multiple comparisons (Figure 2B)]. However, the reduction in the maximal effect of DAMGO produced by CMT was not observed in PAG neurons from βarr-2 knockout mice [Figure 2C; two-way anova comparing DAMGO inhibition in cells from βarr-2 knockout vehicle and CMT animals showed a significant interaction for concentration (P < 0.001), but not treatment (P = 0.571)]. DAMGO inhibited ICa in vehicle-treated βarr-2 knockout mice by a maximum of 28 ± 1% and in neurons from chronic morphine-treated mice to 31 ± 2%. DAMGO inhibited ICa in a similar proportion of PAG neurons from untreated or vehicle-treated mice in each genotype (70%, χ2, P = 0.8) and this proportion was not significantly changed by CMT (χ2, P = 0.53 in wild-type mice, χ2, P = 0.49 in βarr-2 knockouts). ICa density did not differ between naïve animals of either genotype (wt, 196 ± 12 pA/pF, n = 30; βarr-2 knockouts 174 ± 16 pA/pF, n = 19, P = 0.29), nor did it differ between cells from treated animals (Figure 3C,D). The inhibition of ICa by the GABAB agonist baclofen was also similar in each treatment group (Figures 1 and 3A, B).

Figure 1.

Time plots and current traces illustrating the effects of the MOPr agonist DAMGO and the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen on voltage-dependent calcium channel currents (ICa) in PAG neurons from βarr-2 knockout mice treated with vehicle (A) or chronic morphine (B). Currents were elicited by depolarizing the cells from −90 to 0 mV, and were recorded as described in the Methods section. The time plots represent the amplitude of the inward currents measured at the same time as the peak of the control current. Drugs were added for the duration of the bars. Example traces are of at least six similar experiments for each concentration of drug illustrate the reversible inhibition of ICa by various concentrations of DAMGO and baclofen. The effects of these drugs did not differ significantly in cells isolated from vehicle- and morphine-treated mice.

Figure 2.

Concentration–response relationships for DAMGO inhibition of ICa in PAG neurons from (A) untreated wild-type and βarr-2 knockout mice, (B) vehicle and chronically morphine-treated wild-type mice and (C) βarr-2 knockout mice. Each point represents the mean ± SEM of at least 6 cells, curves were fitted to the pooled data. DAMGO potency and maximal effect did not differ between untreated mice of either genotype, while the maximum effect of DAMGO was reduced in neurons from chronically morphine-treated wild-type but nor βarr-2 knockout animals (P < 0.05, two-way anova followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test).

Figure 3.

Baclofen inhibition of ICa and amount of ICa in PAG neurons is not altered by chronic morphine treatment in (A) wild-type or (B) βarr-2 knockout mice. The inhibition of ICa by submaximally effective concentrations of the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen was tested by applying the drug to opioid-sensitive neurons repetitively stepped from −90 to 0 mV. Bars represent the mean ± SEM. of 6–10 cells. Current density in opioid sensitive cells (C) in cells from wild-type mice and (D) in βarr-2 knockout mice. Currents represent the peak inward current elicited by a step from −90 to 0 mV normalized to the cell capacitance. Bars represent the mean ± SEM of 22–30 cells.

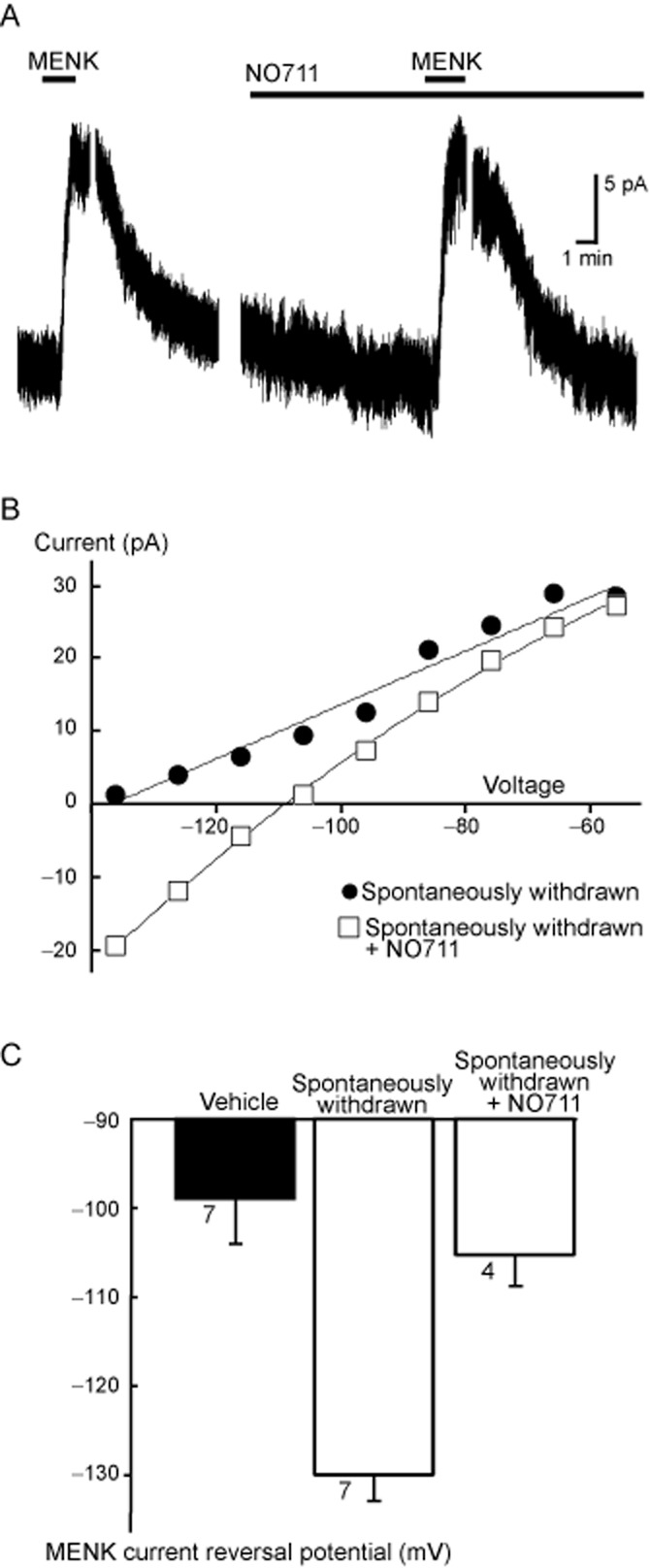

In PAG neurons, withdrawal from CMT stimulates a PKA-dependent increase of the GAT-1 cation conductance. The increased GAT-1 activity is sensitive to opioid inhibition, and therefore during opioid withdrawal, it can be detected by changes in the MENK ([Met]5enkephalin) current reversal potential. When MENK is reducing the GAT-1 cation conductance and increasing the G-protein coupled, inwardly rectifying K channel (GIRK) conductance, the MENK reversal potential will be much more negative than Ek (Bagley et al., 2005b). Superfusion of MENK produced an outward current in PAG neurons voltage clamped at −56 mV in slices from both vehicle- and chronic morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout mice (Figure 4). In neurons from vehicle-treated mice, the ME current reversed polarity at a potential of −100 ± 5 mV, close to the K equilibrium potential in these conditions (−103 mV), as we have previously reported in wild-type mice (Bagley et al., 2005b; 2011). In neurons from chronic morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout mice, the MENK-induced current reversed in only 3 of 7 cells. In the neurons where the MENK current did not reverse polarity at the most negative potential tested, the reversal potentials was assigned a value of −136 mV, a conservative approach we adopted in previous studies to deal with technical inability to determine extremely negative reversal potentials (Bagley et al., 2005b; 2011). The nominal reversal potential for the 7 cells was −130 ± 3 mV. Subsequent superfusion of MENK in the presence of the GAT-1 inhibitor, NO-711, resulted in currents that reversed polarity at significantly more positive potentials than in the absence of NO-711 (P < 0.05), and close to the value for MENK currents in neurons from vehicle-treated mice (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Morphine withdrawal-induced activation of GABA transporter 1 (GAT-1) currents is preserved in βarr-2 knockout mice. (A) A continuous recording of the membrane current of a PAG neuron taken from a chronically morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout mouse. The neuron was voltage clamped at −56 mV. Breaks in the current trace occur when step current–voltage relationships were examined. Met-enkephalin (MENK, 10 μM) was applied twice, the second time in the presence of the GAT-1 inhibitor NO-711. (B) The current-voltage relationship was generated by stepping to the potentials indicated in the same cell as shown in (A). In this cell, the control MENK current did not reverse at the most negative potential tested (−136 mV), but the current reversed close to the calculated EK (−103 mV) in the presence of the NO-711. This cell is representative of four similar experiments. (C) A summary of the reversal potentials of MENK-induced currents in PAG neurons from βarr-2 knockout mice treated with vehicle or chronic morphine. The bars represent the mean ± SEM of the number of cells indicated next to the bars. Cells where the current did not reverse at the most negative potential (3 of 7 cells for spontaneously withdrawn condition) tested were nominally assigned a reversal potential of −136 mV.

Discussion

In this study, we have found that the presence of βarr-2 is required for the reduction in acute MOPr signalling seen in PAG neurons following CMT, but it is not required for the expression of increased GAT-1 activity during withdrawal. These results in single neurons relevant for the anti-nociceptive actions of morphine are consistent with previous findings of lack of cellular tolerance in locus coeruleus neurons from βarr-2 knockout mice (Dang et al., 2011; Quillinan et al., 2011) and establish for the first time that a cellular adaptation in PAG neurons that contributes to opioid withdrawal behaviour (Bagley et al., 2005b; 2011) is not disrupted by the knockout. The findings are consistent with behavioural studies in βarr-2 knockout mice, which reported reduced tolerance to morphine (Bohn et al., 2000; 2002) but a normal (Bohn et al., 2000) or partially blunted (Raehal et al., 2011) naloxone-precipitated withdrawal response. It remains possible that βarr-2-related adaptations in populations of neurons other than PAG contributing to opioid withdrawal contribute to the blunted withdrawal response reported by Raehal et al. (2011).

Inhibition of ICa in PAG neurons by activation of MOPrs is mediated via βγ subunits of the Gi/Go proteins activated by the receptor (Williams et al., 2001) and represents a direct and rapid measure of receptor/G-protein coupling in an intact cell. A reduction in G-protein βγ subunit-mediated MOPr coupling in animals treated with sustained release morphine has been reported in locus coeruleus (Christie et al., 1987; Connor et al., 1999a; Dang et al., 2011), sensory neurons (Johnson et al., 2006) as well as PAG (Bagley et al., 2005a), so it appears to be a common cellular response to continuous morphine treatment. The maintenance of unperturbed MOPr signalling in single PAG neurons from chronically morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout animals is also consistent with data showing absence of morphine tolerance to the reduction in MOPr-stimulated GTPγS binding to membranes from the brainstem of βarr-2 knockout mice (Bohn et al., 2000).

The present finding that the sensitivity of inhibition of ICa by a MOPr agonist was not affected by βarr-2 knockout in PAG neurons is comparable to the modestly blunted coupling to inwardly rectifying K-currents in locus coeruleus neurons (Dang et al., 2009; 2011) and inhibition of ICa in sensory neurons (Walwyn et al., 2007). By contrast, using GTPγS assays to assess agonist activated MOPr function in untreated βarr-2 knockouts, opioid sensitivity was reported to be profoundly enhanced in PAG (Bohn et al., 1999) and brainstem (Bohn et al., 2000), and less so in the spinal cord (Bohn et al., 2002) membranes. There is no obvious explanation for the differences between the data obtained with electrophysiology and GTPγS binding, particularly in PAG, other than the very different nature of the assays. Which assay is a more faithful reflection of MOPr function is uncertain; however, electrophysiological assays are carried out in relatively intact cells in real time and so any issues of acute receptor desensitization or re-organization of signalling complexes during membrane preparation are minimized. It is also possible that the results differ because the experimental approaches reflect MOPr activity in different cellular compartments. Modulation of ICa by MOPr is assayed, of course, only in the cell body, whereas the GTPγS assay reflects a composite of membranes from cell body, dendritic and nerve terminal compartments. The possibility that regulation of MOPr function differs between soma/dendrites and nerve terminals, in neurons, including PAG neurons, has been raised by several studies (Haberstock-Debic et al., 2005; Fyfe et al., 2010; Pennock et al., 2012).

A cellular hallmark of withdrawal in PAG is PKA-dependent increases in GAT-1 currents (Bagley et al., 2005b; 2011). PAG neurons recorded in brain slices from chronically morphine-treated βarr-2 knockout mice display increased GAT-1 currents during withdrawal as previously reported. These results are consistent with those of Bohn et al. (2000), who showed that the characteristic withdrawal-induced elevations in cAMP observed in chronically morphine-treated brain tissue was preserved in βarr-2 knockouts.

In the present study, we found no difference in the potency of DAMGO to inhibit ICa in PAG neurons from untreated animals. Similarly, MOPr coupling to ion channels in neurons from βarr-2 knockout animals has consistently been found to be similar to or even somewhat reduced from that of wild types (Walwyn et al., 2007; Dang et al., 2009). By contrast, behavioural studies of βarr-2 knockout animals observed enhanced anti-nociceptive responses to morphine (Bohn et al., 1999; Mittal et al., 2012).

The role of βarr-2 in acute MOPr regulation has been established most firmly in vitro, with many studies reporting that altering βarr-2 levels promoted or inhibited MOPr trafficking and signalling. In general, morphine was less effective at mediating arrestin-dependent processes than more efficacious agonists such as met-enkephalin, DAMGO or etorphine, although this does not mean that morphine is ineffective at producing reductions in receptor signalling (e.g. Borgland et al., 2003; Dang and Williams, 2005; Arttamangkul et al., 2008). Recent results indicate that MOPr interactions with βarr-2 are not required for desensitization of signalling or internalization of MOPrs in response to opioid ligands in locus coeruleus neurons, and in vivo studies show that anti-nociception produced by efficacious opioids such as fentanyl and etorphine is also unaffected in βarr-2 knockout mice. Several possible explanations have been advanced for why morphine actions in vivo are most sensitive to βarr-2 deletion, despite the in vitro evidence suggesting that the interaction is weak. These explanations include cell-type specific interactions between morphine-activated MOPrs and βarr-2 (Haberstock-Debic et al., 2005), redundant pathways for the attenuation of signalling induced by high efficacy agonists but not by morphine or perhaps that acute receptor desensitization in response to efficacious agonists does not diminish their signalling to a degree observable in behavioural assays. Recent data have demonstrated a GPCR kinase 2/βarr-2-mediated pathway for MOPr desensitization in locus coeruleus (Dang et al., 2009), but this pathway is only unmasked when a parallel ERK pathway is concomitantly blocked. Bailey et al. (2009) used in vivo viral-mediated gene transfer to transfect locus coeruleus neurons with dominant negative mutants to show that GRK2 is required for desensitization induced by DAMGO. The preservation of the modest amounts of morphine-induced receptor desensitization and internalization in the locus coeruleus of βarr-2 knockout mice suggests that morphine may also recruit the ERK pathway (Arttamangkul et al., 2008).

Studying morphine-induced adaptations is important because morphine and closely related analogues are the still among the most widely prescribed opioid analgesics and the morphine pro-drug heroin is also one of the most widely abused opioids. However, it should be borne in mind that βarr-2 is likely to interact with many different GPCRs and ion channels whose activity also modifies the functional outputs of opioid-sensitive neurons and circuits. Thus, any changes in mouse behaviour associated with morphine exposure are likely to also reflect contributions from these other systems. Deletion of βarr-2 can, in some circumstances, modulate the cellular response to acute and chronic morphine (this study, Dang et al., 2011; Walwyn et al., 2007), but the maintenance of crucial cellular adaptations in morphine-tolerant βarr-2 knockout animals indicates that βarr-2 interactions with MOPrs are not crucial for the development of morphine dependence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (project grant 1011979 to M. J. C. and M. C., fellowship 1045964 to M. J. C.). We thank Drs Lefkowitz and Caron for generously providing the β-arr2 knockout mice.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- CMT

chronic morphine treatment

- GAT-1

GABA transporter type 1

- GIRK

G-protein-coupled, inwardly rectifying K channel

- GTPγS

guanosine 5-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- ICa

voltage-gated calcium channel

- MENK

[Met]5enkephalin

- MOPr

µ-opioid receptor

- PAG

periaqueductal grey

- βarr-2

β-arrestin-2

Author contributions

M. C., E. E. B. and B. C. C. designed, conducted and analysed experiments. M. C. and M. J. C. conceived the study and wrote the article. All authors have seen the final article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander SP, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The concise guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arttamangkul S, Quillinan N, Low MJ, von Zastrow M, Pintar J, Williams JT. Differential activation and trafficking of μ-opioid receptors in brain slices. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:972–979. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley EE, Chieng B, Christie MJ, Connor M. Opioid tolerance in periaqueductal grey neurons isolated from mice chronically treated with morphine. Br J Pharmacol. 2005a;146:68–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley EE, Gerke MB, Vaughan CW, Hack SP, Christie MJ. GABA transporter currents activated by protein kinase A excite midbrain neurons during opioid withdrawal. Neuron. 2005b;45:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley EE, Hacker J, Chefer VI, Mallet C, McNally GP, Chieng BC, et al. Drug-induced GABA transporter currents enhance GABA release to induce opioid withdrawal behaviours. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1548–1554. doi: 10.1038/nn.2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CP, Oldfield S, Llorente J, Caunt CJ, Teschemacher AG, Roberts L, et al. Involvement of PKCα and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 in agonist-selective desensitization of μ-opioid receptors in mature brain neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking β-arrestin 2. Science. 1999;286:2495–2498. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin F, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Opioid receptor desensitization by β-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–723. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Differential mechanisms of morphine antinociceptive tolerance revealed in arrestin-2 knockout mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10494–10500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10494.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Connor M, Osbourne PB, Christie MJ. Opioid agonists have different efficacy profiles for G protein activation, rapid desensitization, and endocytosis of μ-opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18776–18784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:384–396. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Williams JT, North RA. Cellular mechanisms of opioid tolerance: studies in ingle brain neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;32:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Borgland S, Christie MJ. Continued morphine modulation of calcium channel currents in acutely isolated locus coeruleus neurons from morphine-dependent rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1999a;128:1561–1569. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Schuller A, Pintar JE, Christie MJ. Opioid receptor modulation of calcium channel current in periaqueductal grey neurons from C57B16/J mice and mutant mice lacking MOR-1. Br J Pharmacol. 1999b;126:1553–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BM, Christie MJ, Devi L, Toll L, Traynor JR. Challenges for opioid receptor nomenclature: IUPHAR Review 9. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:317–323. doi: 10.1111/bph.12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang VC, Williams JT. Morphine-induced μ-opioid receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1127–1132. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang VC, Napier IA, Christie MJ. Two distinct mechanisms mediate acute μ-opioid receptor desensitization in native neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3322–3327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4749-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang VC, Chieng B, Azriel Y, Christie MJ. Cellular morphine tolerance produced by βarrestin-2-dependent impairment of μ-opioid receptor resensitization. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7122–7130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5999-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe LW, Cleary DR, Macey TA, Morgan MM, Ingram SL. Tolerance to the antinociceptive effect of morphine in the absence of short-term presynaptic desensitization in rat periaqueductal grey neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:674–680. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.172643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberstock-Debic H, Kim KA, Yu YJ, von Zastrow M. Morphine promotes rapid, arrestin-dependent endocytosis of μ-opioid receptors in striatal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7847–7857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5045-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack SP, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Modulation of GABA release during morphine withdrawal in midbrain neurons in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram SL, Vaughan CW, Bagley EE, Connor M, Christie MJ. Enhanced opioid efficacy in opioid dependence is caused by an altered signal transduction pathway. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10269–10276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10269.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EE, Chieng B, Napier I, Connor M. Decreased μ-opioid receptor signaling and a reduction in calcium current density in sensory neurons from chronically morphine treated mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:947–955. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal N, Tam M, Egbuta O, Desai N, Crawford C, Xie C-W, et al. Evidence that behavioural phenotypes of morphine in βarr2-/- mice are due to the unmasking of JNK signalling. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1953–1962. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Fossum EN, Levine CS, Ingram SL. Antinociceptive tolerance revealed by cumulative intracranial microinjections of morphine into the periaqueductal gray in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennock RL, Dicken MS, Hentges ST. Multiple inhibitory G-protein-coupled receptors resist acute desensitization in the presynaptic but not postsynaptic compartments of neurons. J Neurosci. 2012;32:10192–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1227-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillinan N, Lau EK, Virk M, von Zastrow M, Williams JT. Recovery from μ-opioid receptor desensitization after chronic treatment with morphine and methadone. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4434–4434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4874-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raehal KM, Bohn LM. The role of β-arrestin2 in the severity of antinociceptive tolerance and physical dependence induced by different opioid pain therapeutics. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raehal KM, Schmid CL, Groer CE, Bohn LM. Functional selectivity at the μ-opioid receptor: implications for understanding opioid analgesia and tolerance. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:1001–1019. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walwyn W, Evans CJ, Hales TG. β-Arrestin2 and c-Src regulate the constitutive activity and recycling of μ-opioid receptors in dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5092–5104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1157-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Ingram SL, Henderson G, Chavkin C, von Zastrow M, Schulz S, et al. Regulation of μ-opioid receptors: desensitization, phosphorylation, internalization, and tolerance. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:223–254. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]