Abstract

Severe maternal morbidity and mortality have been rising in the United States. To begin a national effort to reduce morbidity, a specific call to identify all pregnant and postpartum women experiencing admission to an intensive care unit or receipt of 4 or more units of blood for routine review has been made. While advocating for review of these cases, no specific guidance for the review process was provided. Therefore, the aim of this expert opinion is to present guidelines for a standardized severe maternal morbidity interdisciplinary review process to identify systems, professional, and facility factors that can be ameliorated, with the overall goal of improving institutional obstetric safety and reducing severe morbidity and mortality among pregnant and recently pregnant women. This opinion was developed by a multidisciplinary working group that included general obstetrician–gynecologists, maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, certified nurse–midwives, and registered nurses all with experience in maternal mortality reviews. A process for standardized review of severe maternal morbidity addressing committee organization, review process, medical record abstraction and assessment, review culture, data management, review timing, and review confidentiality is presented. Reference is made to a sample severe maternal morbidity abstraction and assessment form.

To begin a national effort to reduce maternal morbidity, a specific call to identify all pregnant and postpartum women experiencing admission to an intensive care unit or receipt of 4 or more units of blood for routine review has been made.1 The increasing rates of maternal mortality and severe morbidity in the United States have been well-documented in recent publications.2–5 It is therefore appropriate that efforts should be focused on reducing maternal severe morbidity and death.6–8 Reviews of maternal deaths in order to identify likely preventable deaths and interventions to reduce preventable deaths have been widespread for years.9,10 However, the call to similarly implement routine standardized identification and evaluation of severe maternal morbidity cases by every birthing facility in the United States has only recently been highlighted.1

Although several methods have been proposed to identify women with severe maternal morbidity, the criteria proposed by Callaghan et al were admission of the mother to an intensive care unit (ICU) or receipt of 4 or more units of blood.1,11 These criteria were chosen because they are simple and have high sensitivity and specificity for identifying pregnant and recently postpartum women with severe morbidity.12,13 The sensitivities were 63% to 86% when each was used individually, but up to 100% if combined.12,13 It should be emphasized that while these criteria are reliable markers of potential severe maternal morbidity, the fact that a patient was admitted to an ICU or received 4 or more units of blood alone do not imply that care and systems were substandard. In fact, it is the review of the case that ultimately determines 1) if the case is a severe maternal morbidity and 2) whether there were improvements in processes or care necessary. While advocating for review of these cases, no specific guidance for the review process were provided.1

The aim of this document is to present a suggested standardized severe maternal morbidity review process to identify systems, professional, and facility factors that could be ameliorated, with the overall goal of improving institutional obstetric safety and reducing severe morbidity and mortality among pregnant and recently pregnant women. This opinion was developed by a multidisciplinary working group that included general obstetrician–gynecologists, maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, certified nurse–midwives, and registered nurses. These individuals were appointed by their respective organizations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN), American College of Nurse-Midwives, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and all authors have state or national experience with maternal mortality review. The review process, organization, and forms were modeled after Illinois and California maternal mortality review processes and forms9 (personal communication, Elizabeth Lawton, CA Department of Public Health, Maternal Child and Adolescent Health Division, and Elliot Main, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, California Pacific Hospital; 2013).

The following recommendations for the development and maintenance of a severe maternal morbidity review process are intended as guidelines and could be modified at individual centers. This process is consistent with The Joint Commission’s template for root cause analysis to be employed for sentinel events.14 Of note, maternal deaths are considered sentinel events and thus reviewed by root cause analysis. We suggest that the morbidity review process herein described could be modified and used for maternal death review if appropriate for local process.

1. Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Committee Organization

Hospital or birth facility leadership appoints a standing Severe Maternal Morbidity Committee. This may require new bylaws.

Committee membership is multidisciplinary and reflects the professional make-up of clinicians and staff who provide or support maternity services institutionally. Example members are: obstetricians, family physicians, certified nurse–midwives, and advanced-practice nurses; anesthesia personnel; registered nurses providing antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum care; and members of the hospital Quality Improvement team and administration. A public member or patient advocate could be considered. Ad-hoc members representing other expertise can be invited as deemed necessary. If there are learners such as residents or fellows, they should be represented as well.

The Committee has a chairperson, an individual responsible for minutes, and an individual responsible for data management.

2. Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Process

At a minimum, the Committee will review all pregnant or postpartum women receiving 4 or more units of blood or admitted to an ICU. These criteria may be expanded as needed by an individual center.

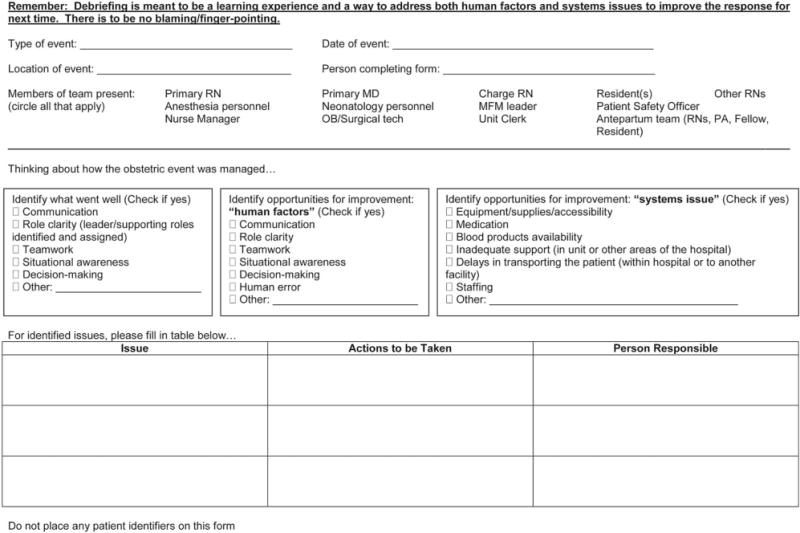

For each case of severe maternal morbidity, a debriefing with involved care providers, which does not replace the standardized review, is suggested and ideally occurs proximate to the severe maternal morbidity. Information obtained from the debriefing can be retained for the standardized review process. There are several debrief tools available (https://www.cmqcc.org/resources/1533/download and http://www.med.unc.edu/ticker/toolkit/teamwork/brief-debrief-form). Another example is a debrief tool developed by C. Lee and D. Goffman, who gave permission for its inclusion in this article (Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) (Fig. 1).

The severe maternal morbidity review should be conducted at each facility, if possible.

Centers with a low volume of deliveries or obstetric providers may opt to partner with centers within their perinatal region, or outsource their reviews to a center with sufficient staff and providers to conduct the reviews.

Leaders from regional perinatal centers, state maternal and child health departments, state medical and nursing societies, and ACOG districts could identify experts who will be available to assist local committees.

Chart abstraction for patients whose care is being reviewed will be done by an individual trained in the abstraction and review process.

Data abstraction and review should follow a specific format to facilitate consistent collection of meaningful information that can be adequately evaluated. One method of achieving this is to use a specific form for data abstraction and review. A good example of such a form is the Severe Maternal Morbidity Abstraction and Assessment Form (www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org). This form is consistent with the root cause analysis and action framework as it applies to obstetric sentinel events.14 Other tools such as the fishbone diagram for root cause analysis or sentinel event could also be used. The goals of the abstraction are to capture specific data as well as the essence of the severe morbidity, including a narrative with a detailed time line of the pertinent events. To aid the abstractor in identifying key issues, a sample list of disease-specific questions associated with severe maternal morbidity are included (Appendix). These types of questions can be used for any morbidity and are meant only as a guide.

The abstracted data should be presented to the Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Committee for their review and assessment.

The assessment portion of the Severe Maternal Morbidity Abstraction and Assessment Form is completed based on the results of the Committee’s review of the case. Each review should conclude with an assessment of whether there were opportunities to improve outcome. If identified, these opportunities are enumerated, and specific recommendations for potential alterations in outcome should be suggested to the appropriate responsible institutional person or department.

Each institution should have agreed-upon mechanisms in place to implement any recommendations and to evaluate the effects of the suggested changes.

Fig. 1.

Sample debrief tool for maternal severe morbidity or death—Montefiore Medical Center. Figure courtesy of C. Lee and D. Goffman. Used with permission.

Kilpatrick. Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Process. Obstet Gyncol 2014.

3. Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Culture

Reviews are not conducted as peer review, which addresses credentialing and formal discipline issues, but rather as expert review focused broadly on improving systems and care provision. If a case has peer-review issues, then these should have been identified and handled in the existing institutional peer-review process. Expert review may be anonymous and has no authority to discipline individuals, but rather looks for opportunities to reduce preventable morbidity and mortality. State laws often protect expert review from discovery, but this must be determined on a state-by-state basis. The culture and tone of the review process must be nonjudgmental, and the final assessment, with respect to potential improvements in care, rendered as dispassionately as possible. One example of such an approach is the “Just Culture,” whose key principles include educating caregivers about risk, holding them responsible for following best practices, creating a safe haven around reporting, and recognizing what can and cannot be controlled.15

4. Data Management

Data, including outcome data, are trended. The identification of potentially improvable measures as the primary goal of these reviews is to recognize systems, provider, and patient factors that are amenable to alterations that could improve outcomes in future cases. Using a consistent data form, such as the Severe Maternal Abstraction and Assessment Form, will facilitate acquisition of analyzable data.

Each facility will determine the best method to disseminate important recommendations for improvement in outcomes locally and more broadly.

Data from internal facility reviews could be aggregated at regional levels (ie, perinatal regional, state, and ACOG districts, and AWHONN sections and chapters). De-identified aggregate data reviewed at regional and national levels could help to identify trends and, more importantly, opportunities for improvement in the delivery of obstetric health care. ACOG districts may accumulate reports and share trend and action data with others.

Consideration could be given to utilizing Patient Safety Organizations in this national effort to consolidate and disseminate appropriate findings. Patient Safety Organizations were developed by the Patient Safety Improvement Act of 2005 (www.pso.ahrq.gov) and provide privilege and confidentiality to clinicians and health care organizations to collect and analyze data to improve quality by reducing risks associated with patient care.

5. Review Timing

Depending on the severity of the event, reviews should occur soon after the event and include obtaining information from the debriefing. The more severe the event, the more proximate the review should be to the event. Hospitals that wish to review a broader list of morbidities or that have a large number of cases may choose to have the Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Committee meet regularly.

6. Confidentiality and Protection from Discovery

The Severe Maternal Morbidity Review Committee should be sanctioned by the hospital and protected from discovery. State codes and relevant statutes must be reviewed to determine if protection or authority exists for maternal morbidity review. State ACOG sections and hospital associations may be helpful in identifying statutes and lobbying state legislative bodies for appropriate changes if needed.

All Committee members sign affidavits of confidentially.

CONCLUSIONS

Severe maternal morbidity in the United States has significantly increased since the late 1990s, affecting at least 50,000 women per year.3 Without efforts to systematically identify and evaluate cases of severe maternal morbidity in a multidisciplinary format, effective and sustained morbidity reduction would seem unlikely. We conclude that every U.S. birthing facility should implement a standardized review process for cases of severe maternal morbidity in order to identify system and caregiver improvement opportunities that may prevent future instances of serious maternal morbidity and mortality. Our recommendations are intended to be guidelines for review, and the Severe Maternal Morbidity Abstraction and Assessment Form is one example of a format to review severe maternal morbidity. Because of the proven high sensitivity and specificity for severe maternal morbidity and the relative ease of use, we strongly recommend utilizing the criteria of ICU admission or receipt of 4 or more units of blood to identify women with severe maternal morbidity.1,11–13 These criteria may be modified or expanded as needed by an individual center. It should be emphasized that these criteria, in and of themselves, do not convey a judgment about the care of the patient. Only review of the case can provide such insight. Therefore, neither ICU admission nor transfusion of 4 or more units of blood should be used as quality measures.

Individual facility review and assessment, with implementation of recommendations, are expected to improve local care. However, also important is the potential to aggregate de-identified data at regional and national levels to allow sufficient numbers for statistical analysis, which may lead to significant systems improvement in care for all pregnant and postpartum women.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anna Santa-Donato, MSN, RN, for her significant contribution to the severe maternal morbidity abstraction and assessment form.

Jeanne Mahoney RN, BSN, is an employee of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College). All opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the policies and views of the College. Any remuneration that the authors receive from the College is unrelated to the content of this article.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Appendix: Sample Disease-Specific Questions to Guide Abstraction

Hemorrhage

Was the hemorrhage recognized in a timely fashion?

Were signs of hypovolemia recognized in a timely fashion?

Were transfusions administered in a timely fashion?

Were appropriate interventions (eg, medications, balloons, sutures) used?

Were modifiable risk factors (eg, oxytocin, induction, chorioamnionitis, delay in delivery) managed appropriately?

Was sufficient assistance (eg, additional doctors, nurses, or others) requested and received?

Hypertensive disease

Was hypertension recognized appropriately?

Did the woman appropriately receive magnesium sulfate?

Was severe hypertension treated in a timely fashion?

Was the woman delivered at the appropriate time relative to her hypertensive disease?

Were any complications related to hypertensive disease managed appropriately?

Infectious disease, sepsis

Was the diagnosis of sepsis or infectious disease made in a timely fashion?

Were appropriate antibiotics used after diagnosis? How long to treatment?

Did the woman receive appropriate volume of intravenous fluids?

Were significant modifiable risk factors for infectious complications identified?

Other diseases as necessary

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Callaghan WM, Grobman WA, Kilpatrick SJ, Main EK, D’Alton M. Facility-based identification of women with severe maternal morbidity: it is time to start. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:978–81. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan WM, MacKay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 2001–2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:133.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1029–36. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, Dahhou M, Rouleau J, Mehrabadi A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:449–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuklina EV, Meikle SF, Jamieson DJ, Whiteman MK, Barfield WD, Hillis SD, et al. Severe obstetric morbidity in the United States: 1998–2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:293–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181954e5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark SL, Meyers JA, Frye DR, McManus K, Perlin JB. A systematic approach to the identification and classification of near-miss events on labor and delivery in a large, national health care system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:441–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Alton ME, Bonanno CA. Putting the “M” back in maternal-fetal medicine. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;207:442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, Kilpatrick S. Defining a conceptual framework for near-miss maternal morbidity. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2002;57:135–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kilpatrick SJ, Prentice P, Jones RL, Geller S. Reducing maternal deaths through state maternal mortality review. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1–5. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis G. Saving mothers’ lives: the continuing benefits for maternal health from the United Kingdom (UK) confidential enquiries into maternal deaths. Semin Perinatol. 2012;36:19–26. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senanayake H, Dias T, Jayawardena A. Maternal mortality and morbidity: epidemiology of intensive care admissions in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;27:811–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox S, Brown M, Simonson L, Kilpatrick S. A scoring system identified near-miss maternal morbidity during pregnancy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:716–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You WB, Chandrasekaran S, Sullivan J, Grobman W. Validation of a scoring system to identify women with near-miss maternal morbidity. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:21–4. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Joint Commission. Framework for conducting root cause analysis and action plan. 2013 Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/Framework_for_Conducting_a_Root_Cause_Analysis_and_Action_Plan/. Retrieved May 16, 2014.

- 15.Marx D. Patient safety and the “just culture”: a primer for health care executives. New York (NY): Columbia University; 2001. Available at: http://www.safer.healthcare.ucla.edu/safer/archive/ahrq/FinalPrimerDoc.pdf. Retrieved May 16, 2014. [Google Scholar]