Abstract

Objectives

Although critically ill children are at increased risk for developing deep venous thrombosis, there are few pediatric studies establishing the prevalence of thrombosis or the efficacy of thromboprophylaxis. We tested the hypothesis that thromboprophylaxis is infrequently used in critically ill children even for those in whom it is indicated.

Design

Prospective multinational cross-sectional study over four study dates in 2012.

Setting

Fifty-nine PICUs in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, and the United States.

Patients

All patients less than 18 years old in the PICU during the study dates and times were included in the study, unless the patients were 1) boarding in the unit waiting for a bed outside the PICU or 2) receiving therapeutic anticoagulation.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Of 2,484 children in the study, 2,159 (86.9%) had greater than or equal to 1 risk factor for thrombosis. Only 308 children (12.4%) were receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (e.g., aspirin, low-molecular-weight heparin, or unfractionated heparin). Of 430 children indicated to receive pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis based on consensus recommendations, only 149 (34.7%) were receiving it. Mechanical thromboprophylaxis was used in 156 of 655 children (23.8%) 8 years old or older, the youngest age for that device. Using nonlinear mixed effects model, presence of cyanotic congenital heart disease (odds ratio, 7.35; p < 0.001) and spinal cord injury (odds ratio, 8.85; p = 0.008) strongly predicted the use of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis, respectively.

Conclusions

Thromboprophylaxis is infrequently used in critically ill children. This is true even for children at high risk of thrombosis where consensus guidelines recommend pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.

Keywords: anticoagulants, deep venous thrombosis, heparin, pediatric intensive care unit, pulmonary embolism, venous thromboembolism

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are important but underappreciated problems in critically ill children. In adults admitted in the ICU, the prevalence of clinically apparent DVT and PE is at least 20 per 1,000 patients with a frequency of at least 14.5 per 1,000 patients despite pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis (pTP) (1). Critically ill adults with no contraindication to anticoagulation are strongly recommended to receive pTP based on strong evidence that pTP decreases the prevalence of DVT and PE in this population (2). In children admitted in the PICU, the prevalence of clinically apparent DVT and PE is at least 9.3 per 1,000 patients with a frequency of at least 7.4 per 1,000 patients (3). There are no recommendations on pTP specific to critically ill children because of paucity of data (4). Thromboprophylaxis guidelines for children with other conditions are mainly based on expert opinion (4).

It is unclear which groups of children should be targeted for thromboprophylaxis. In our survey of clinician leaders from North American PICUs, respondents report that they are likely to prescribe pTP for mechanically ventilated adolescents but not for younger patients (5). Presence of hypercoagulability, prior DVT, or cavopulmonary anastomosis also increased the self-reported likelihood of pTP. Although our survey provided clinician leaders' opinions regarding thromboprophylaxis practice, reported practice often overestimates actual practice (5, 6). It also did not estimate the use of mechanical thromboprophylaxis (mTP), which may be more commonly used in older children (6).

In the present study, we hypothesized that this lack of evidence would result in infrequent and highly variable use of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children. We estimated the frequency of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children and identified patient, physician, and PICU characteristics associated with thromboprophylaxis. We wanted to understand the process of care variables surrounding the provision of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a prospective multinational cross-sectional observational study on four study dates (February 1, May 1, August 1, and November 1, 2012). PICUs from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, Sociedad Espanola de Cuidados Intensivos Pediatricos, and selected PICUs in Asia were invited to participate. All PICUs collected data in each of the study dates. The institutional review boards of each PICU approved the study, including waiver of signed consent.

All patients less than 18 years old hospitalized in the PICU during the study dates and times were included in the study, unless they were 1) boarding in the unit waiting for non-PICU beds or 2) receiving therapeutic anticoagulation.

At 9 am, local time of each study date, demographics, preadmission history, and data from current admission were collected from each eligible patient. Data were abstracted from the medical records into standardized case report forms by trained abstractors who were typically physicians or nurses. Site investigators and data abstractors (Appendix 1) were provided a manual containing detailed descriptions of each data point. Each abstractor was required to enter data from standardized sample patients into the database prior to the first study date. Feedback was provided to ensure accurate data collection and entry. Data included patient characteristics known to be associated with DVT or PE (4, 7–10), indications and contraindications for pTP based on the American College of Chest Physicians' (ACCP) guidelines for pediatric patients (4), and use of thromboprophylaxis. We also collected characteristics of central venous catheters (CVCs) because the presence of CVC is the most significant risk factor for DVT in children (11, 12). Selected characteristics of the patient's attending physician and PICU were also collected. Data were managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at Washington University at St. Louis School of Medicine (13).

Data Definitions and Outcome Measures

We defined patient qualification for pTP as 1) any patient admitted to the PICU and 2) based on the ACCP pediatric guidelines, any patient with dilated cardiomyopathy, cavopulmonary anastomosis, cyanotic congenital heart disease, end-stage renal disease, or pulmonary hypertension who had no contraindication to anticoagulation. Presence of anticipated surgery, confirmed and suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, intracranial hemorrhage documented radiologically, or nonintracranial hemorrhage requiring blood product transfusion contraindicated anticoagulation (4, 14). A patient who was administered a pTP agent or used an mTP device within 24 hours prior to the study date and time was considered to be receiving thromboprophylaxis. Aspirin, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), IV unfractionated heparin (UFH), subcutaneous UFH, warfarin, and clopidogrel constituted pTP. In the absence of a standard definition, we defined greater than 10 U/hr of UFH infused through the CVC as thromboprophylactic dose and less than or equal to 10 U/hr of UFH as dose for CVC patency (11).

The primary outcome measure was the frequency of pTP defined as the proportion of all patients in the PICU receiving pTP. Our secondary objective was to identify factors associated with prescribing thromboprophylaxis. We included all children 8 years old or older in the analyses on mTP because mTP could only be used in this age group (11).

Statistical Analyses

Patients were divided into three age strata: infants less than 1 year old, children 1–13 years old, and adolescents more than 13 years old to reflect the bimodal distribution of pediatric DVT (11, 12). Data from the four study dates were combined. Continuous and categorical variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and absolute counts and percentages, respectively.

We had reasonable expectation that clinical practice and types of patients varied between PICUs. We also wanted to make inferences for an average patient seen at any of the PICUs, which in turn were a sample and not a census of all representative PICUs. We used a nonlinear mixed effect model with logistic linkage with the probability of pTP as outcome, given certain predictors treated as fixed effects factors (i.e., patient, physician, and PICU characteristics) and PICUs treated as random effects factor. We conducted bivariate logistic regression analyses for each characteristic and included characteristics with p value less than 0.20 in the final model. We used the Akaike information criterion to find the final parsimonious model. We used this model to determine center effect. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were reported. A similar approach was used for mTP.

Analyses were performed using Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Assuming that the frequency of pTP was 16% (15), a total of 2,360 patients from the four study dates were needed to achieve a 95% CI of ±1.5% around the mean. If each PICU had on average 10 patients per study date (16), a minimum of 59 PICUs was needed to complete enrollment.

Results

Patient, Physician, and PICU Characteristics

A total of 2,484 of 2,909 patients (85.4%) hospitalized in 59 PICUs from seven countries (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, and the United States) were included. Patients were equally distributed during the four study dates with 674, 609, 587, and 614 patients for study dates 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Patient, physician, and PICU characteristics are presented in Table 1. The attending physicians analyzed might not represent unique physicians, as some might have been the attending physicians during prior study dates. Of the 59 PICUs, 19 (32.2%) had some form of protocol to guide thromboprophylaxis practice.

Table 1. Patient, Physician, and PICU Characteristics of Eligible Patients.

| Patient Characteristics | Number (%) | Physician Characteristics | Number (%) | PICU Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2,484 | n | 468 | n | 59 |

|

| |||||

| Age group | Age group | Location | |||

| < 1 year old | 1,025 (41.3) | ≤ 40 years old | 209 (44.7) | Australia and New Zealand | 8 (13.6) |

| 1–13 years old | 1,191 (48.0) | 41–50 years old | 160 (34.2) | Canada | 5 (8.5) |

| > 13 years old | 268 (10.8) | > 50 years old | 90 (19.2) | Singapore | 1 (1.7) |

| Unknowna | 9 (1.9) | Spain and Portugal | 15 (25.4) | ||

| United States | 31 (52.5) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Male | 1,389 (55.9) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Race | Gender | Hospital type | |||

| White | 1,697 (68.3) | Male | 248 (53.0) | Academic | 44 (74.6) |

| Black | 369 (14.9) | Female | 211 (45.1) | Community | 15 (25.4) |

| Asian | 134 (5.4) | Unknowna | 9 (1.9) | ||

| Others | 44 (1.8) | ||||

| Unknown | 240 (9.7) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity | Additional specialty | Type | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 416 (16.8) | Pediatrics | 346 (73.9) | Cardiac | 4 (6.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1,843 (74.2) | Others | 99 (21.2) | Medical or surgical | 22 (37.3) |

| Unknown | 225 (9.1) | No other specialty | 23 (4.9) | Mixed | 33 (55.9) |

| Years in practice | Free-standing children's hospital | 41 (69.5) | |||

| ≤ 10 yr | 259 (55.3) | Size | |||

| 11–20 yr | 140 (29.9) | ≤ 10 beds | 14 (23.7) | ||

| > 30 yr | 69 (14.8) | 11–20 beds | 27 (45.8) | ||

| 21–30 beds | 14 (23.7) | ||||

| > 30 beds | 4 (6.8) | ||||

An institutional review board limited some of the data collected from the physicians.

The majority of patients were at risk for DVT. The list of risk factors considered is presented in Figure 1. The median number of risk factors was 2 (IQR, 1–4). A total of 2,159 patients (86.9%) had ≥ 1 risk factor, 1,712 patients (68.9%) ≥ 2 risk factors, and 1,217 patients (49.0%) ≥ 3 risk factors. The most common risk factor was the presence of CVC. More than half of the patients (1,312, 52.8%) had at least 1 CVC (median, 1; IQR, 0–1) with the nontunneled (667 of 1,498 CVC, 44.5%), peripherally inserted (i.e., peripherally inserted central catheter: 563, 37.6%), and tunneled (189, 12.6%) types being most common. CVCs were most often placed peripherally (479, 32.0%), in the femoral vein (355, 23.7%) or in the internal jugular vein (348, 23.2%).

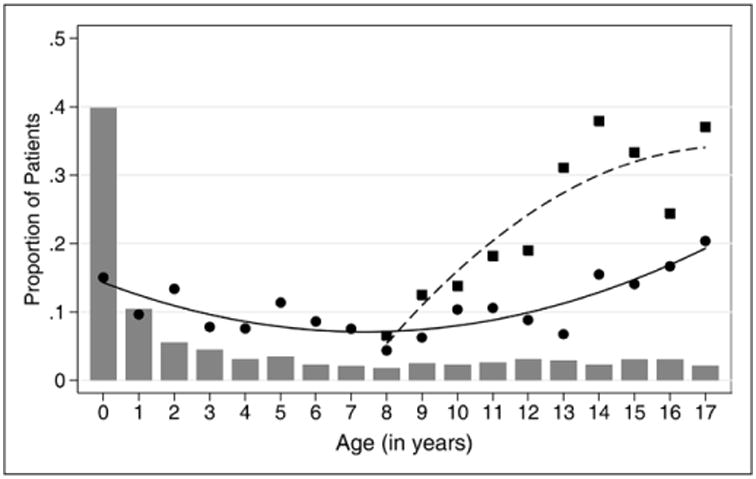

Figure 1.

The frequency of pharmacologic (A) and mechanical (B) thromboprophylaxis was highly variable depending on the presence of risk factor. Each bar represents the proportion of patients with the risk factor. The denominator is the total number of patients in the study. The circles represent the proportion of patients at risk receiving thromboprophylaxis. The denominator is the total number of patient with the risk factor. Because mechanical thromboprophylaxis can only be used in children 8 years old or older, the proportion of patients at risk in (B) represents only the subset of patients in this age group. CHD = congenital heart disease.

Pharmacologic Thromboprophylaxis

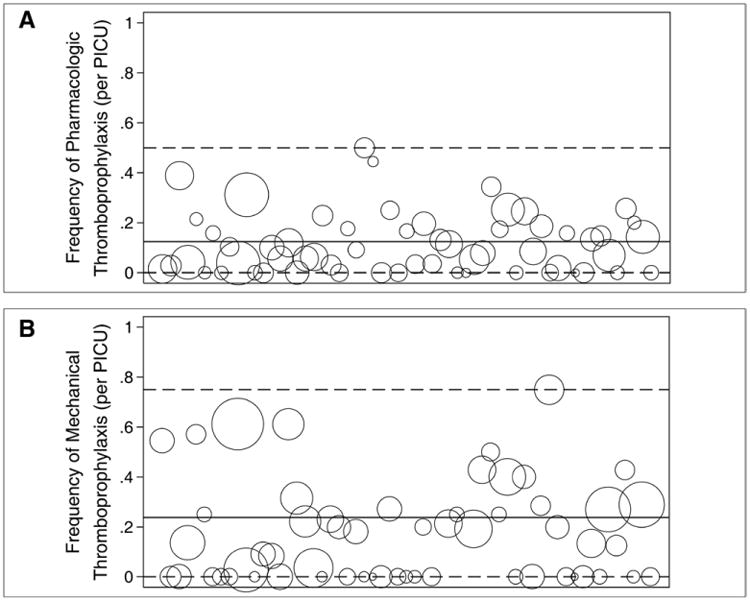

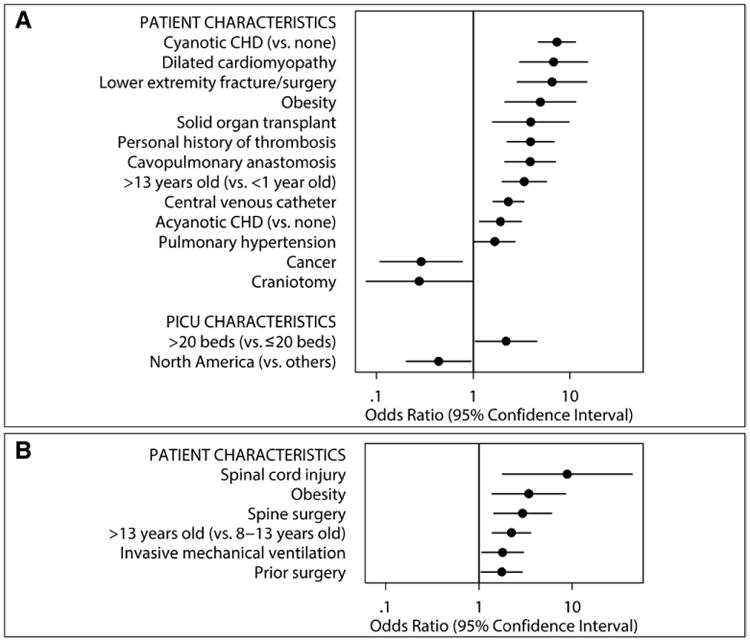

A total of 308 of 2,484 patients (12.4%) in the PICU were receiving pTP. Of 146 neonates less than 1 month old, 30 (20.6%) were on pTP. The frequencies of pTP during the four study dates were 11.6%, 12.2%, 12.4%, and 13.5%. Of 430 patients indicated to receive pTP based on the ACCP guidelines, 149 (34.7%) were receiving pTP. The frequency of pTP was highest in adolescents and in infants (Fig. 2). Of 57 neonates indicated to receive pTP, 16 (28.1%) were on pTP. pTP varied depending on the risk factor present and ranged from 0% to 60.2% (Fig. 1A). The frequency of pTP for each of the indications in the ACCP guidelines were as follows: cavopulmonary anastomosis, 60.2%; cyanotic congenital heart disease, 42.6%; dilated cardiomyopathy, 42.5%; pulmonary hypertension, 26.1%; and end-stage renal disease, 4.0%. Use of pTP increased as the number of risk factors increased—14.0% in patients with ≥ 1 risk factor, 16.0% with ≥ 2 risk factors, and 18.5% with ≥ 3 risk factors (p < 0.001). After adjusting for surrogates of severity of illness (i.e., patient diagnoses and interventions), there was a center effect with the frequency of pTP across PICUs ranging from 0% to 50.0% (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). Patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease were most likely to receive pTP (OR, 7.35; 95% CI, 4.75–11.37; p < 0.001) (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/A827). Although the presence of CVC was independently associated with pTP (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.60–3.35; p < 0.001), it was prescribed in only 17.0% of patients with CVC. No physician characteristics were associated with pTP.

Figure 2.

The frequency of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis was highest at the extremes of age while the frequency of mechanical thromboprophylaxis initially increased but seemed to plateau at 13 years old or older. Filled circles represent pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis; filled squares represent mechanical thromboprophylaxis; gray bars represent proportion of patients per year; solid line represents fitted values (pharmacologic); and dashed line represents fitted values (mechanical).

Figure 3.

The frequency of pharmacologic (A) and mechanical (B) thromboprophylaxis was highly variable across PICUs. Each bubble represents a PICU. The size of the bubble represents the relative number of patients in the PICU during the study dates. The x-axis represents the identification number assigned to each PICU. The solid line represents the mean frequency of thromboprophylaxis for the entire patient cohort while the dashed lines represent the range.

Figure 4.

Different patient and PICU characteristics were independently associated with pharmacologic (A) and mechanical (B) thromboprophylaxis. The x-axes are in the logarithmic scale. Only the risk factors with p values less than 0.05 in the multivariable model are presented. CHD = congenital heart disease.

Aspirin was the most commonly used agent (143 of 308 patients on pTP, 46.4%), primarily because of patients with congenital heart disease. Of the 143 patients on aspirin, 105 (73.4%) had congenital heart disease. LMWH was the next most commonly used agent (113 of 308 patients, 36.7%), most of which were enoxaparin (110 of 113 patients, 97.4%).

Mechanical Thromboprophylaxis

A total of 156 of 655 (23.8%) patients 8 years old or older received mTP. Of these, 21 patients were also on pTP. Pneumatic/sequential compression device was used in 134 of 156 patients (85.9%) and graduated compression stockings were used in 35 of 156 patients (22.4%).

The frequencies of mTP over the four study dates were 22.5%, 24.0%, 28.7%, and 19.3%. The prevalence of mTP varied depending on patient's age, the risk factor present, and PICU. mTP increased with age up to about 13 years old (Fig. 2). The frequency of mTP ranged mostly from 0% to 50.0% depending on which risk factor was present (Fig. 1B) and from 0% to 75.0% per PICU (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). The presence of spinal cord injury had the highest likelihood of mTP (OR, 8.85; 95% CI, 1.79–43.82; p = 0.008) (Fig. 4B; Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/A828). Age more than 13 years old and obesity were both independently associated with pTP and mTP. No physician characteristics were associated with mTP.

Discussion

This is the first multinational study to describe thromboprophylaxis practice in a broad group of PICU patients. We found that 86.9% of children in the PICU had greater than or equal to 1 risk factor for DVT. Overall, use of thromboprophylaxis was low. The frequency of pTP use in all children was 12.4%. Only 34.7% of patients indicated to receive pTP based on the ACCP pediatric guidelines were on pTP. mTP was used in only 23.8% of all children 8 years old or older. Thromboprophylaxis was also highly variable depending on the patient's age, risk factor present, and PICU where the patient was admitted.

Comparing our results to our survey on stated use of thromboprophylaxis (5), surveyed clinicians overestimated the use of pTP in adolescents and underestimated pTP use in younger patients. In contrast to our survey where LMWH was thought to be the most commonly used agent (5), aspirin was the most commonly used agent in actual practice. Although aspirin is not recommended to prevent thrombosis aside from some children with cardiac problems (4), it was recommended as a thromboprophylactic agent for a select group of adults with cancer (17) and those undergoing total joint arthroplasty (18).

Although this is the first multinational study of pediatric thromboprophylaxis, prior single-center studies reported that 10–22% of selected patients in the PICU were on pTP (15, 19, 20). The use of pTP in our study was lower than in critically ill adults where a multinational observational study found that 85% of them were receiving pTP (21). The frequency of mTP use in our study was similar to the 23% use reported in adults with contraindication to pTP (21, 22). Similar data on mTP use in children are not available.

Our study shows that 86.9% of children have greater than or equal to 1 risk factor for DVT (3, 4, 12, 23, 24). The lack of evidence on the efficacy of thromboprophylaxis in children and underestimation of the risk of DVT may explain the infrequent use of pTP. The low compliance with the ACCP guidelines may be because the evidence is weak (4). It is possible that the use of normal saline, heparin flushes, or intermittent urokinase suggested by ACCP to maintain line patency (4) may be misconstrued as adequate thromboprophylaxis (25). The risk of DVT in critically ill children is likely underappreciated as reported incidences of clinically apparent cases significantly underestimate the overall incidence of DVT (11, 26). Pediatric intensivists often do not consider clinically silent DVT to require treatment (27) despite evidence to the contrary (28–30). The nonuse of pTP may be appropriate. The weak evidence for the ACCP recommendations implies that not giving pTP may be a reasonable option. Despite the grade of evidence, we compared pTP utilization to expected utilization as suggested by the ACCP guidelines to provide a point of comparison. The higher frequency of mTP compared with pTP suggests that clinicians may be unwilling to accept the risk of bleeding (5) even though it appears to be low (20). Only 1.7% of patients in our study were at high risk of bleeding (31). There are no studies demonstrating the efficacy of mTP in children despite its widespread use.

The high variability in the use of thromboprophylaxis is concerning and has been reported in hospitalized adults (22). Unwarranted variations in clinical practice can lead to worse outcomes and higher cost of care (32). In contrast to adults where problems implementing the available evidence likely cause practice variations (22), the lack of evidence to guide practice in children likely contributes to this practice variability. It is challenging to determine whether the variability is acceptable or unwarranted without any sense on what practice should be.

We identified patient characteristics that predicted thromboprophylaxis. Consistent with our survey (5), cyanotic congenital heart disease, immobility, obesity, prior DVT, cavopulmonary anastomosis, and adolescence were independent predictors of pTP. Spinal cord injury increased the likelihood of pTP in our survey but not in the current study. This may reflect the perceived complications from bleeding in this population because spinal cord injury strongly predicted mTP in our study. Acquired hypercoagulability and major bleeding, which affected the likelihood of pTP in our prior survey, were not associated with pTP in our current study. The wide CI around the ORs for these predictors likely reflects the low number of events per predictor variable (33) and may partly explain the discrepancy. Presence of CVC, a predictor of pTP in our current study, did not increase the likelihood of pTP in our survey. The discrepancy may be related to our definition of UFH doses as some clinicians use higher doses to maintain line patency (25). We were unable to capture the clinicians' intent for heparin dosing in patients with CVC. The ACCP pediatric guidelines recommend against systemic anticoagulation to prevent CVC-related DVT based on inadequately powered trials (4).

The major strengths of our study are its multinational design and the large sample size. Inclusion of a number of countries increased the generalizability of our results. The large sample size allowed us to obtain more precise estimates of the frequency of thromboprophylaxis and to concurrently evaluate predictors of thromboprophylaxis. This is the first multinational study to describe the use of mTP in children. The use of thromboprophylaxis in children is a topic of confusion and controversy. Our study compared practice with guidelines, even though they are limited.

Our results should be viewed in light of some limitations. The focus of our study was to understand the process of care variables surrounding the use of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children. Although important, we did not collect clinical outcomes, that is, DVT, PE, or bleeding, because of our cross-sectional study design. Use of thromboprophylaxis was defined as receipt of thromboprophylaxis within 24 hours prior to the study date and time. It is possible that the thromboprophylaxis status of some patients may have been different at other times during their PICU stay potentially leading to inaccuracies in the frequency of thromboprophylaxis use. It is unlikely that the frequency of pTP is significantly different from what we report based on prior single-center studies (15, 19, 20). We are unable to determine the number of PICU days that a patient was on thromboprophylaxis because of our study design. PICUs were not randomly selected and developing countries were not represented. Although the majority of the participating PICUs had cardiac patients, only four (6.8%) were cardiac PICUs. We may have underestimated the number of cardiac patients on pTP. The primary data source was the medical record, which may have some error introduced during interview and documentation. We used standardized case report forms with operational definitions to maximize data consistency. It is possible that the attending physician was not solely responsible for the decision for thromboprophylaxis. This may partly explain the lack of correlation between the attending physicians' characteristics and thromboprophylaxis.

Conclusions

The low frequency and high variability in thromboprophylaxis practice highlight the need for well-designed studies to inform practitioners of the appropriateness of pTP in critically ill children. Variability around thromboprophylaxis should be reduced. However, in the absence of evidence, it is hard to know the optimal practice to improve care. We have identified risk factors that are important to practitioners and should be prioritized for future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) BloodNet (http://www.bloodnetresearch.org) and the PALISI (http://www.palisi.org) Scientific Steering Committee for their assistance during the design and completion of the study and their insightful reviews of the article.

This work was performed at Akron Children's Hospital; Alberta Children's Hospital; Baylor College of Medicine; Baystate Medical Center; Boston Children's Hospital; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke; Centre mere-enfant Soleil du CHU de Quebec; Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte; Children's Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha and Nebraska Medical Center; Children's Hospital and Research Center Oakland; Children's Hospital at Westmead; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Children's Hospital of Wisconsin; Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota; CHU Sainte-Justine University of Montreal; Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York; Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruna; Connecticut Children's Medical Center; Dell Children's Medical Center of Central Texas; Doernbecher Children's Hospital; Duke University Medical Center; Gregorio Maranon General University Hospital; Helen DeVos Children's Hospital; Hospital Clinico Universitario de Santiago; Hospital Dona Estefania; Hospital Infantil Universitario Miguel Servet; Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesus; Hospital Pediatrico Coimbra; Hospital Regional Universitario Materno Infantil Carlos Haya; Hospital Sao Joao; Hospital Universitario Materno Infantil Las Palmas de Gran Canaria; Joseph M Sanzani Children's Hospital at Hackensack University Medical Center; KK Women's and Children's Hospital; Mater Children's Hospital; Montreal Children's Hospital; Nationwide Children's Hospital; Nuestra Senora de Candelaria Hospital; Penn State Children's Hospital; Princess Margaret Hospital; Riley Hospital for Children; Royal Children's Hospital Brisbane; Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne; Sant Joan de Deu Hospital; St. Louis Children's Hospital; Starship Children's Hospital; Stony Brook University Medical Center; Sydney Children's Hospital; University Hospital of Salamanca; University of California at San Francisco; University of Rochester Medical Center; University of Virginia; Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide; and Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital.

Dr. Faustino received funding from Clinical and Transitional Science Award (CTSA) (grant numbers UL1 TR000142 and KL2 TR000140) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). His institution received grant support from the NIH. Dr. Spinella is a consultant of TerumoBCT and is employed by Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. O'Brien is a consultant of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. O'Brien served as a board member for American Thrombosis and Hemostasis Network, consulted for Bristol Myers (Venous Thromboembolism in Peds: Apixaban), and provided expert testimony for Katie Crott Walsh (for trial). Her institution received grant support from Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society and American Diabetes Association. Dr. Yung is employed by the Women's and Children's Hospital. Dr. Truemper is employed by Children's Specialty Physicians. Dr. Qin received funding from CTSA (grant number UL1 TR000142). Dr. Marohn is employed by the Yale New Haven Hospital. REDCap from Washington University at St. Louis School of Medicine, which was used as the study's data collection tool, was funded through CTSA (grant number UL1 TR000448).

Appendix 1. Prophylaxis Against Hrombosis Practice (Protract) Study Investigators

Akron Children's Hospital—Ann-Marie Brown, MSN; Alberta Children's Hospital—Leena Desai, MSc, Elaine Gilfoyle, MD, MMEd; Baylor College of Medicine—Michelle Goldsworthy, BN, Nancy Jaimon, BSN, MSN, Laura Loftis, MD; Baystate Medical Center—Michael Canarie, MD; Boston Children's Hospital—Daniel Kelly, MD, Adrienne Randolph, MD, MSc; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke—Miriam Santschi, MD, MSc; Centre mere-enfant Soleil du CHU de Quebec—Marc-Andre Dugas, MD, MSc, Louise Gosselin, BN; Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte—Joana Rios, MD; Children's Hospital and Medical Center, Omaha and Nebraska Medical Center—Edward Truemper, MD, MS, Brenda Weidner, BSN; Children's Hospital and Research Center Oakland—Heidi Flori, MD, Julie Simon, RN; Children's Hospital at West-mead—Marino Festa, MD, Karen Walker, PhD, Nicola Watts, PhD; Children's Hospital of Philadelphia—Daniela Davis, MD, MSCE, Mary Ann DiLiberto, BS, William Kamens, BA, Rebecca McIntosh, BA, Brooke Park, BSN, Janice Prodell, RN; Children's Hospital of Wisconsin—Sheila Hanson, MD, MS, Kathleen Murkowski, BS, David Triscari, BS; Children's Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota—Chris Leonard, BA, Jeffrey Nowak, MD, Alison Overman, BA; CHU Sainte-Justine University of Montreal—Mariana Dumitrascu, MD, Jacques Lacroix, MD, Marisa Tucci, MD; Cohen Children's Medical Center of New York—Aaron Kessel, MD, James Schneider, MD, Todd Sweberg, MD; Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruna—Angela Ferrer Barba, MD, Carmen Ramil, MD; Connecticut Children's Medical Center—Christopher Carroll, MD, MS; Dell Children's Medical Center of Central Texas—LeeAnn Christie, MSN, Renee Higgerson, MD; Doernbecher Children's Hospital—Aileen Kirby, MD; Duke University Medical Center—Ira Cheifetz, MD, Kyle Rehder, MD, Samantha Wrenn, BS; Gregorio Maranon General University Hospital—Jesus Lopez-Herce, MD, PhD; Helen DeVos Children's Hospital—Nabil Hassan, MD, Akunne Ndika, MBBS, MPH; Hospital Clinico Universitario de Santiago—Antonio Rodriguez-Nunez, MD, PhD, Sara Trabazo-Rodriguez, MD; Hospital Dona Estefania—Maria Ventura, MD; Hospital Infantil Universitario Miguel Servet—Juan Pablo Garcia Íñiguez, MD, Paula Madurga Revilla, MD; Hospital Infantil Universitario Niño Jesus—Maria Isabel Iglesias Bouzas, MD; Hospital Pediatrico Coimbra—Maria Dionisio, MD; Hospital Regional Universitario Materno Infantil Carlos Haya—Patricia García Soler, MD; Hospital Sao Joao—Miguel Fonte, MD; Hospital Universitario Materno Infantil Las Palmas de Gran Canaria— Antonio Jimenez, MD, Joseph M. Sanzani; Children's Hospital at Hackensack University Medical Center—Shira Gertz, MD; KK Women's and Children's Hospital—Loh Tsee Foong, MBBS, MMed, Anuradha Menon, MBBS; Maria Fareri Children's Hospital—Simon Li, MD, MPH; Mater Children's Hospital—Sara Mayfield, BHSc, Andreas Schibler, MD; Montreal Children's Hospital—Yasser Kazzaz, MBBS, Samara Zavalkoff, MDCM; Nationwide Children's Hospital—Sue Cunningham, BSN, Kristin Greathouse, MS, BSN, Dianna Hidalgo, BS, Sarah O'Brien, MD, MSc, Kami Perdue, BS, Lisa Steele, BSN; Nuestra Senora de Candelaria Hospital—Jose Sebastian Leon Gonzalez, MD; Penn State Children's Hospital—Debra Spear, RN, Robert Tamburro, MD; Princess Margaret Hospital—Simon Erickson, MBBS; Riley Hospital for Children—Stephanie Fritz, RN, Christi Rider, LPN, Mark Rigby, MD, PhD; Royal Children's Hospital Brisbane—Debbie Long, PhD, Anthony Slater, MBBS, Tara Williams, BSN; Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne— Warwick Butt, MBBS, Carmel Delzoppo, BSc, Sophie Syddall, PhD; Sant Joan de Deu Hospital—Iolanda Jordan, PhD, Lluisa Hernandez, MD; St. Louis Children's Hospital—Rachel Jacobs, BA, Philip C. Spinella, MD, Cindy Terrill, CCRP; Starship Children's Hospital—John Beca, MBChB, Tracey Bushell, BA, Miriam Rea, BN, Claire Sherring, RN; Stony Brook University Medical Center—Kathleen Culver, DNP, Margaret Parker, MD; Sydney Children's Hospital—Gary Williams, MBBS, Janelle Young, MApSc, MPH; University Hospital of Salamanca— Mirella Gaboli, MD, PhD, Pedro Gomez de Quero, MD; University of California at San Francisco—Victoria Lo, BS, Anil Sapru, MD, MAS; University of Rochester Medical Center—Jill M. Cholette, MD, L. Eugene Daugherty, MD; University of Virginia—Robin Kelly, RN, Douglas Willson, MD; Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide—Georgia Letton, BA, Michael Yung, MD; and Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital— Edward Vincent S. Faustino, MD, Kim Marohn, MD, Veronika Northrup, MPH, Li Qin, PhD, Sree Pemira, MD, Joana Tala, MD, Elyor Vidal, MPH.

Footnotes

See also p. 1317.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

For information regarding this article, vince.faustino@yale.edu

References

- 1.Patel R, Cook DJ, Meade MO, et al. Burden of Illness in venous ThromboEmbolism in Critical care (BITEC) Study Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Burden of illness in venous thromboembolism in critical care: A multicenter observational study. J Crit Care. 2005;20:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alhazzani W, Lim W, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Heparin thromboprophylaxis in medical-surgical critically ill patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2088–2098. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828cf104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgerson RA, Lawson KA, Christie LM, et al. National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institution's Pediatric Intensive Care Unit FOCUS group. Incidence and risk factors associated with venous thrombotic events in pediatric intensive care unit patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:628–634. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318207124a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monagle P, Chan AK, Goldenberg NA, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e737S–e801S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faustino EV, Patel S, Thiagarajan RR, et al. Survey of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1773–1778. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182186ec0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Brien SH, Haley K, Kelleher KJ, et al. Variation in DVT prophylaxis for adolescent trauma patients: A survey of the Society of Trauma Nurses. J Trauma Nurs. 2008;15:53–57. doi: 10.1097/01.JTN.0000327327.83276.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrory MC, Brady KM, Takemoto C, et al. Thrombotic disease in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12:80–89. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181ce7644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortel TL. Acquired thrombotic risk factors in the critical care setting. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S43–S50. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9ccc8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parker RI. Thrombosis in the pediatric population. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S71–S75. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c9cce9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenberg NA, Bernard TJ. Venous thromboembolism in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:305–322. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faustino EV, Spinella PC, Li S, et al. Incidence and acute complications of asymptomatic central venous catheter-related deep venous thrombosis in critically ill children. J Pediatr. 2013;162:387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faustino EV, Lawson KA, Northrup V, et al. Mortality-adjusted duration of mechanical ventilation in critically ill children with symptomatic central venous line-related deep venous thrombosis. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1151–1156. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820eb8a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e195S–e226S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harney KM, McCabe M, Branowicki P, et al. Observational cohort study of pediatric inpatients with central venous catheters at “intermediate risk” of thrombosis and eligible for anticoagulant prophylaxis. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2010;27:325–329. doi: 10.1177/1043454210369895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santschi M, Jouvet P, Leclerc F, et al. PALIVE Investigators; Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network (PALISI); European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC) Acute lung injury in children: Therapeutic practice and feasibility of international clinical trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:681–689. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d904c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2189–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johanson NA, Lachiewicz PF, Lieberman JR, et al. American academy of orthopaedic surgeons clinical practice guideline on: Prevention of symptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1756–1757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Arca MJ, et al. Effectiveness of clinical guidelines for deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of venous thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1292–1297. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824964d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, et al. Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital: A patient-safety and quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1326–e1332. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh KC, Oh D, Sittipunt C, et al. VOICE Asia Investigators. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in medical ICU patients in Asia (VOICE Asia): A multicenter, observational, cross-sectional study. Thromb Res. 2012;129:e152–e158. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen AT, Tapson VF, Bergmann JF, et al. ENDORSE Investigators. Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): A multinational cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2008;371:387–394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Journeycake JM, Buchanan GR. Catheter-related deep venous thrombosis and other catheter complications in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulet SL, Amendah D, Grosse SD, et al. Health care expenditures associated with venous thromboembolism among children. Thromb Res. 2012;129:583–587. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke M, Cruz ED, Koehler J, et al. A multicenter survey of heparin prophylaxis practice in pediatric critical care. J Intensive Care Med. 2011;26:314–317. doi: 10.1177/0885066610392501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raffini L, Huang YS, Witmer C, et al. Dramatic increase in venous thromboembolism in children's hospitals in the United States from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1001–1008. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotsakis A, Cook D, Griffith L, et al. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Clinically important venous thromboembolism in pediatric critical care: A Canadian survey. J Crit Care. 2005;20:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biss TT, Brandão LR, Kahr WH, et al. Clinical features and outcome of pulmonary embolism in children. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:808–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Derish MT, Smith DW, Frankel LR. Venous catheter thrombus formation and pulmonary embolism in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1995;20:349–354. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950200603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck JR, Connors RH, Coon WW, et al. Pulmonary embolism in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(81)80700-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massicotte P, Julian JA, Gent M, et al. PROTEKT Study Group. An open-label randomized controlled trial of low molecular weight heparin for the prevention of central venous line-related thrombotic complications in children: The PROTEKT trial. Thromb Res. 2003;109:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wennberg J. Time to tackle unwarranted variations in practice. BMJ. 2011;342:687–690. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.