Abstract

Cataract-induced by sodium selenite in suckling rats is one of the suitable animal models to study the basic mechanism of human cataracts formation. The aim of this present investigation is to study the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-mediated activation of unfolded protein response (UPR), overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and suppression of Nrf2/Keap1-dependent antioxidant protection through endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway and Keap1 promoter DNA demethylation in human lens epithelial cells (HLECs) treated with sodium selenite. Lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected rats generated overproduction of ROS in lens epithelial cells and newly formed lens fiber cells resulting in massive lens epithelial cells death after 1–5 days. All these lenses developed nuclear cataracts after 4–5 days. Sodium selenite treated HLECs induced ER stress and activated the UPR leading to release of Ca2+ from ER, ROS overproduction and finally HLECs death. Sodium selenite also activated the mRNA expressions of passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes such as Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b, and active DNA demethylation pathway enzyme, Tet1 leading to DNA demethylation in the Keap1 promoter of HLECs. This demethylated Keap1 promoter results in overexpression of Keap1 mRNA and protein. Overexpression Keap1 protein suppresses the Nrf2 protein through ERAD leading to suppression of Nrf2/Keap1 dependent antioxidant protection in the HLECs treated with sodium selenite. As an outcome, the cellular redox status is altered towards lens oxidation and results in cataract formation.

Keywords: cataracts, ER stress, sodium selenite, unfolded protein response, Keap1 promoter demethylation, human lens epithelial cells

1. Introduction

Age-related cataract (ARC) is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. The prevalence of ARCs is increasing rapidly with the global aging of population. The incidence of cataract is known to increase with age, and no region of the world is immune to the age-related onset and development of cataract [1]. Cataract surgery is the only available and effective means of treatment. But it should be provided to all those in need as there are no known effective means of preventing the ARCs. Further, prevention of ARCs by attenuating the key cataractogenic risk factors seems to be a best way for the development of nonsurgical approaches. These strategies not only enhance the quality of life but also suppress the public health burden [2]. Further, animal model of cataracts are essential to develop these strategies. Even though, there are several animal model of cataracts available, sodium selenite-induced cataract is well-accepted and studied model.

Selenium is an indispensable micronutrient that exerts various vital biological functions [3]. However, supranutritional levels of selenium (>1 μM) acts as a highly toxic pro-oxidant, and promote the reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by its metabolites through redox catalysis [4, 5] and possibly by mitochondrial membrane dysfunction [6]. Selenite is also well-known to induce nuclear cataract within 4–6 days before the completion of critical lens maturation period in neonatal rats [7, 8]. Further, selenite-induced cortical cataracts principally involved in protein degradation, liquefaction, and abnormal fibrogenesis, and are histologically well described [8].

Selenite-induced cataractous lenses are reported to have altered lenticular Ca2+ homeostasis [9, 10], decreased ATP content [11], loss of reduced glutathione (GSH), elevated NADP/NADPH ratio [10, 12], increased glycerol-3-phosphate level [13], and DNA double strand breaks at initial days [14]. Also, an elevated level of Ca2+ is known to activate m-calpain and significant proteolysis of β-crystallin and α-spectrin [15], instigating their insolubility [16, 17], and finally development of lens opacity by phase separation in selenite-induced cortical and nuclear cataractous lenses [18, 19].

Supranutritional doses of selenite is known to change the conformational structure of Bax protein [20], and an anion exchanger 1 (AE1) protein by binding with its sulfhydryl groups in the cytoplasmic domain [21]. Selenite also binds with microtubule proteins and tubulin by means of disulfide bridges between tubulin sulfhydryl groups inducing a large conformational change of the protein [22]. It is recognized that protein conformational changes induce the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the lens, which is one of central pathway for cataract formation. If proteins conformation is changed or misfolded, they are retained in the ER for additional processing by ER protein chaperones, especially immunoglobulin heavy-chain binding protein (BiP), and targeting the misfolded proteins terminally for degradation by the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway [23–25]. If the accumulated misfolded proteins are failed to eliminate by the cell, cell death pathways, i.e. chronic unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated. We found that almost all cataractogenic stresses induce ER stress, which triggers all these events [26–30]. We further found a significant loss of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) promoter DNA methylation in diabetic cataractous lenses, which was not significant in clear lenses and in cultured human lens epithelial cells (HLECs; SRA01/04) [31]. Keap1 is an oxidative stress-sensing protein and is a negative regulator of nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2).

Nrf2 is a central nuclear transcriptional factor, which controls more than 200 stress-associated genes, including 20 antioxidant genes [32]. Moreover, UPR upregulates intracellular ROS production [33] and activates Nrf2 to maintain the cellular redox homeostasis from oxidative damage by controlling the inducible expression of many cytoprotective genes [34–36]. Under terminal UPR, the level of Nrf2 decreases due to proteasomal degradation and proteolysis by m-calpain and caspase-3 and caspase-1 [37, 38]. Recently, Liu and his colleagues demonstrated Nrf2 translocation into the nucleus in response to sulforaphane in HLECs, which coincides with lenticular protection against oxidative stress [39].

Previously, we established the association of unfolded protein response with various cataractogenic stressors, such as valproic acid [30], low glucose with hypoxic conditions [26], high glucose [28], homocystine [26] in HLECs as well as in lenses enucleated from galactose fed rats [29]. This results in the overproduction of ROS and ER-Ca2+ release leading to HLECs death [30]. These studies demonstrated the associations of unfolded protein response activation, Nrf2 dependent antioxidant system failure and loss of Keap1 promoter DNA methylation because of altered active and passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs. As an outcome, cellular redox balance is altered towards lens oxidation and cataract formation.

The present study is hypothesized to study the cataractogenic mechanisms of sodium selenite in LECs, since supranutritional level of sodium selenite alters the conformations of various proteins by oxidizing SH-group in the cysteine residues of several proteins. Our findings highlight the associations between induction of ER stress and UPR activation, ROS overproduction, Nrf2 dependent antioxidant system failure and loss of Keap1 promoter methylation because of altered active and passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs by sodium selenite.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

13-days-old Sprague-Dawley suckling rats were used in this study. The suckling rats were housed with their parents in the clean, sterile, polypropylene cages under standard vivarium conditions (12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to water and food. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Nebraska Animal Care and Use Committee and were in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act (Public Law 91–579) as mandated by the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the procedures recommended by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology resolution on the use and treatment of animals in ophthalmic and vision research were followed. Selenite cataract was induced in the suckling rats by subcutaneously injecting sodium selenite (20 μmol/kg body weight) on postpartum day 14. However, control suckling rats were subcutaneously injected only with saline. The opacity distribution (by surface plot and plot profile) of the control and cataractous lenses were determined from the captured images by ImageJ analysis software [40].

2.2. Cell culture

HLECs (SRA01/04) were cultured overnight in DMEM, High glucose (Life Technologies) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products) under 20% atmospheric oxygen at 37°C. Cells were plated 24 h prior to experiment in DMEM, Low glucose (Life Technologies) under 4% atmospheric oxygen and cultured with 10 μM sodium selenite (Sigma) for the indicated time. At the end of the experiment, the cells were harvested and used for Western blotting, intracellular ROS production and cell death assays, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), and bisulfite genomic DNA sequencing.

2.3. Cell viability/death staining

Rat lenses (4 animals per each group, i.e. 8 lenses in each point) or HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite were stained for cell viability and cell death using viability/cytotoxicity assay kits (Biotium Inc.). After 30 min incubation, cells were washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and subjected to fluorescent microscopic imaging (Nikon, Eclipse TE2000-U) with a green filter (450–490 nm) for viable cells and with a red filter (510–560 nm) for dead cells, respectively [26, 30, 31]. This viability/cytotoxicity assay kit is consisted of calcein AM and ethidium homodimer-III (EthD). Calcein AM is a non-fluorescent substrate that freely passes through the cell membrane and is cleaved by intracellular esterases to form highly fluorescent calcein, which is retained in the live cells and imparts intense green color fluorescence. EthD, a membrane-impermeable fluorescent dye, undergoes a fluorescence enhancement upon binding with nucleic acids and imparts red color fluorescence. EthD is only able to enter into the dead cells, because the plasma membranes of those cells are compromised.

2.4. Intracellular ROS staining

Rat lenses (4 animals per each group, i.e. 8 lenses in each point) or HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite were stained by adding 1 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2-DCFH-DA) (Invitrogen) in PBS for 30 min. Then the cells were washed twice with PBS, and examined under a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Eclipse TE2000-U) with a green filter (450–490 nm) [26, 30, 31].

2.5. TUNEL staining

TUNEL staining was performed with an in situ fluorescent cell death detection kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s protocol using a fluorescent microscope(Nikon, Eclipse TE2000-U) with a green filter (450–490 nm) [28].

2.6. DNA fragmentation

Genomic DNA was isolated from HLECs treated with/without 10 μM sodium selenite using Quick-gDNA™ MicroPrep (Zymo Research) and was separated by electrophoresis in 2% (w/v) agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). After separation, the gel was visualized under UV light using ChemiDoc™ XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad) and analyzed with Image Lab 3.0 software (Bio-Rad).

2.7. Calcium imaging

HLECs were loaded with 5 μM Fluo-3, AM with Pluronic® F-127 (Invitrogen) in DMEM containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice with Ca2+-free DMEM before imaging. 1 μM sodium selenite was added to the cells in Ca2+-free DMEM and time-lapse confocal live imaging was conducted to assess the intracellular Ca2+ changes. Cells earlier exposed to sodium selenite were then challenged with 10 mM caffeine to assess the intracellular Ca2+ changes, if any, for 2 min. Experiments were performed in line-scan mode by using a Zeiss 410 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc.) and field-stimulating cells at 0.25 Hz (10 V for 10 ms), as described previously [30, 41]. Fluo-3 AM was excited by light at 488 nm, and fluorescence was measured at wavelengths of >515 nm.

2.8. Western blotting

HLECs were lysed with RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Western blotting was performed with antibodies specific to Bip (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), p-PERK, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), p-eIF2α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), ER oxidoreductin 1 (Ero1)- Lα, Ero1-Lβ, protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium-transporting ATPase (SERCA), Nrf2, Keap1, glutathione reductase (GR), catalase, ten-eleven translocation 1 protein (TET1), DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) 1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and GAPDH (Novus Biologicals) as described elsewhere [26, 30, 31]. The specificity of each antibody was validated in HLECs prior to conduct experiments. The intensity of each band was normalized to that of GAPDH, and the data were presented as a relative intensity using the ImageJ analysis software [40].

2.9. RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from the HLECs with Quick-RNA™ MicroPrep solution (Zymo Research). The column purified total RNA was reverse transcribed by iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for real-time PCR (Bio-Rad) and was analyzed by MiniOpticon™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) using the SsoFast™ EvaGreen® supermix (Bio-Rad) as described elsewhere [26, 30, 31]. The primer sequences were designed using the ProbeFinder software (Roche) and were synthesized commercially. Primers used for RT-qPCR are listed in Table S1. The specificity of the listed primers was verified by using the in silico PCR (http://insilico.ehu.es/) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information primer blast tool. The PCR products of those primers also visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and verified by DNA sequencing. In addition, the Validated All-in-One™ qPCR primers for Nrf2-target genes such as, glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (Gclc), glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (Gclm), quinone reductase (Nqo1), thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1) and sulfiredoxin-1 (Srxn1) were purchased from GeneCopoeia and catalogs numbers are listed in the Table S2. Briefly, each reaction was carried out in triplicate and three independent experiments were run. Standard curves were prepared to determine individual PCR amplification efficiencies by using a serial dilution of a reference sample and was included in each real-time run to correct for possible variations in product amplification. The relative copy numbers were obtained from the standard curve and were normalized to the values obtained for Gapdh, the internal control. Data acquisition, analysis and PCR efficiencies were done using CFX manager 3.1 software (Bio-Rad).

2.10. Bisulfite genomic DNA sequencing

The genomic DNA from cultured HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h was subjected to bisulfite conversion by EZ DNA Methylation-Direct™ kit (Zymo Research). The bisulfite-modified DNA was amplified by bisulfite sequencing PCR using Platinum® PCR SuperMix High Fidelity (Invitrogen) with primers specific to human Keap1 promoter (Table S3). Then, the amplified PCR products were cleaned by gel extraction with Zymoclean™ Gel DNA recovery kit (Zymo Research), then cloned into pCR® 4-TOPO vectors using TOPO TA Cloning® kit (Invitrogen). The recombinant plasmids were transformed into One Shot® TOP10 chemically competent E. coli (Invitrogen) using the regular chemical transformation method. Plasmid DNA were isolated from about 10 independent clones of each amplicon with PureLink™ Quick Plasmid Miniprep kit (Invitrogen) and then sequenced (High-Throughput DNA Sequencing and Genotyping Core Facility, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE) to determine the status of CpG methylation. Clones with an insert with >99.5% bisulfite conversion, i.e., non-methylated cytosine residues to thymine were included in this study, and the remaining was excluded. Then the sequenced data of each clone was analyzed for DNA methylation in the Keap1 promoter by BISMA software (http://biochem.jacobs-university.de/BDPC/BISMA/) using default filtering threshold settings [42].

2.11. Proteasomal degradation studies

HLECs were precultured with 2.5 μM and 5 μM MG-132 (Selleck Chemicals), a proteasome protease inhibitor for 4 h, then, followed by a washout in regular medium, with or without 2 μM sodium selenite for 24 h. The harvested cells were lysed using RIPA buffer and the proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using the antibodies specific to Keap1 and Nrf2.

2.12. Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± SD, and statistical significance was determined by student’s t test or one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc test, least significant difference using the SPSS (version 15.0) software (SPSS Inc.). Values were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

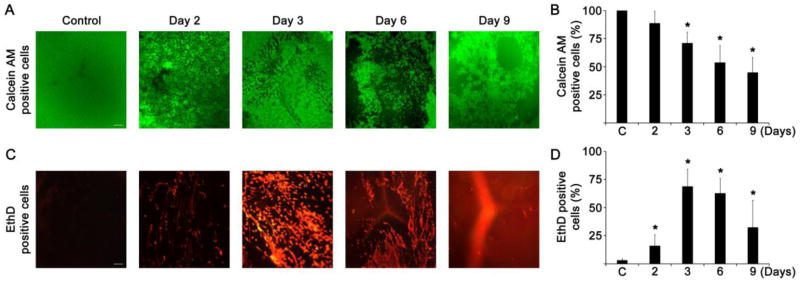

3.1. Selenite induces LECs death and nuclear cataract in 13-days-old suckling rats

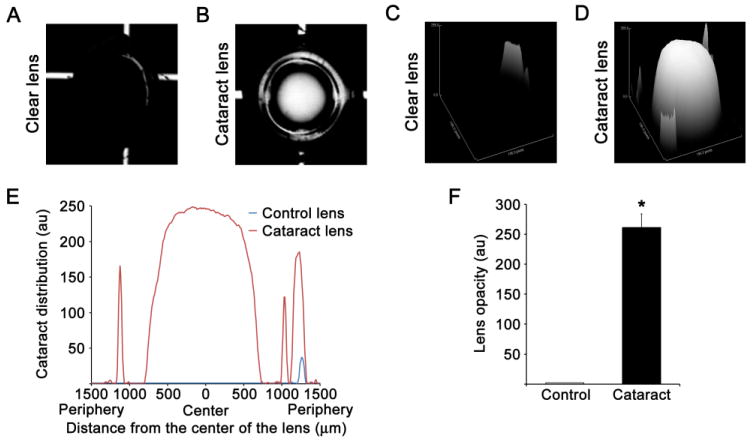

Single subcutaneous injection of sodium selenite (20 μmol/kg body weight) to 13-days-old Sprague-Dawley suckling rats developed cortical opacities and nuclear cataract within 4–6 days. The cell viability/death staining revealed that most of the LECs were alive (Fig. 1A and 1B), and no LECs death (EthD positive cells) were found in the control suckling rats (Fig. 1C and 1D). However, the lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected suckling rats by day 2 and 3 shown various sizes of dark holes all over the LECs with significant amounts of LECs death just under the lens capsule. Further the number of live LECs was decreased significantly, and more than half of the LECs were EthD positive cells by day 6. By day 9, there were not many dead cells seen but the most LECs of equatorial region became like normal LECs. The apparent nuclear cataract was found at day 6 in rats administered with sodium selenite, however, control rats shown clear lens (Fig. 2A and 2B). As shown by densitometry surface plot (Fig. 2C and 2D) and linear plot profiles (Fig. 2E), the lens opacity at day 6 is evident in rats administered with sodium selenite (Fig. 2F). These results suggest that selenite toxicity killed the LECs and possibly fiber cells in first few days and then new LECs are generated in the mitotic zone to recover from the loss of LECs in equatorial region of the lenses.

Fig. 1.

Cell viability and cell death in the lenses enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats. A. Representative photomicrographs of calcein AM stained viable live cells in lenses (n=8) enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for various time course. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. B. Bar graph shows the percentage of live cells measured from the lenses (n=8) enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for various time course. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p<0.05, vs control group. C. Representative photomicrographs of EthD stained dead cells in lenses (n=8) enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for various time course. Significant level of cell death was found in rat lenses injected with sodium selenite between 2 and 6 days. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. D. Bar graph shows the percentage of cell death measured from the lenses (n=8) enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for various time course. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p<0.05, vs control group.

Fig. 2.

Cataract formation in the lenses enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats A. Clear lens enucleated from control rats and photographed in a PBS buffer without background light. B. Cataractous lens enucleated from rats injected with sodium selenite after 6 days, and photographed in a PBS buffer without background light. C. Surface plot of opacity distribution in clear lenses enucleated from saline injected suckling rats at day 6 using ImageJ software. D. Surface plot of opacity distribution in cataractous lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected suckling rats at day 6 using ImageJ software. These surface plots shown that lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected suckling rats at day 6 have compact nuclear opacity in center of the lens. E. Plot profiles made by ImageJ software revealed cataract distribution (y axis) relative to the distance from the center of the lens (x axis). F. Bar graph shows the lens opacity (in terms of arbitrary units) in clear and cataractous lenses. The data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p<0.05, vs control group.

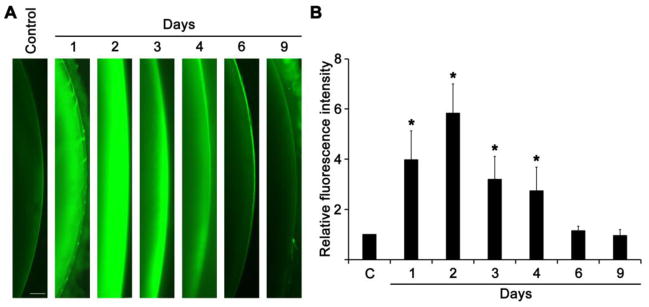

3.2. Selenite induces intracellular ROS overproduction in 13-days-old suckling rat lenses

We enucleated the rat lenses on day 1, day 2, day 3, day 4, day 6, and day 9, after the selenite injection, and stained those lenses for intracellular ROS levels (Fig. 3A and 3B). Overall, the indicative fluorescence of dichlorofluorescein (oxidized form of H2-DCFH-DA) was increased within 24 h, however, the fluorescence was appeared to be high in LECs as well as in lens fiber cells by day 2. But, the fluorescence levels were decreased notably between day 3 and day 4, and nearly undetectable by day 6 and day 9. These results are consistent with others that a 60% decrease of lens free glutathione within 24 h of post-selenite treatment [4, 5, 43, 44]. Further, we found significantly elevated intracellular ROS production by day 2 in the cortical lens fiber cells of lenses enucleated from selenite injected suckling rats than that of other ER stressors such as low glucose with hypoxia [26, 45], homocysteine [26], and tunicamycin [28]. These results suggest that sodium selenite induces exaggerated production of intracellular ROS in the LECs as well as in the newly differentiated lens fiber cells, which can induce the ER stress response, subsequently.

Fig. 3.

ROS production in the lenses (n=8) enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats. A. The representative fluorescent photomicrographs of H2-DCFH-DA staining for ROS production in lenses enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for varying time course. B. Bar graph shows the total fluorescence intensity measured from the images of the lenses enucleated for sodium selenite injected suckling rats for various time course. Background fluorescence level was corrected. The data are presented as mean ± SD. *p<0.05, vs control group. The scale bar indicates 0.25 mm.

3.3. Selenite induces intracellular ROS overproduction and cell death in cultured HLECs

Next, we tried to analyze the ER stress specific proteins in the LECs of lenses enucleated from selenite injected rats by Western blot analysis. Due to detachment of LECs from the capsule, and liquefaction of young lens fiber cells, we could not obtain LECs without significant contaminations with lens fiber proteins. We also could not visualize intracellular Ca2+ release from the ER in the rat lenses treated with sodium selenite. Hence, we decided to study those experiments by using cultured HLECs (SRA01/04) treated with sodium selenite.

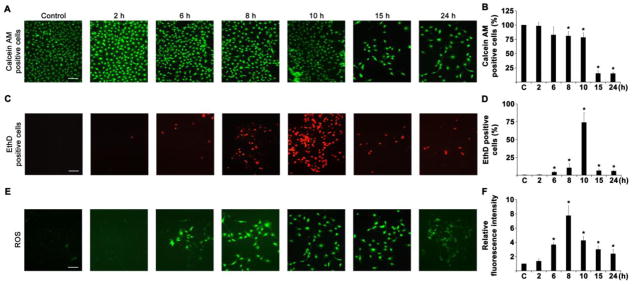

At first step, HLECs were cultured with 10 μM sodium selenite for varying time course and stained for live and dead cells using calcein AM (Fig. 4A and 4B), and EthD staining (Fig. 4C and 4D), respectively. The intracellular ROS production also stained by H2-DCFH-DA staining (Fig. 4E and 4F). The cell death was initiated after 2 h, and reached to a plateau by 10 h in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite. Then, the cell death was decreased significantly after 15 h to 24 h (Fig. 4C and 4D). This decrease is due to washing of floating death cells during washing process, so that the number of live cells also significantly decreased in HLECs treated with μM sodium selenite for 15 h to 24 h (Fig. 4A and 4B). Interestingly, cell death was increased about 2 h after ROS production. Further, ROS production and cell death were occurred much earlier than that of lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected suckling rats. This discrepancy can be generated by the lag times of sodium selenite delivery into the rat lenses.

Fig. 4.

Cell viability, cell death and ROS production in HLECs treated with sodium selenite for varying time course. A. Representative photomicrographs of calcein AM staining for viable live HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. B. Graph shows the percentage of live cells measured from the images of the HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, vs control group. C. Representative photomicrographs of EthD staining for cell death in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. D. Graph shows the percentage of cell death measured from the images of the HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, vs control group. E. Representative fluorescence photomicrographs of H2-DCFH-DA staining for ROS production in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. F. Graph shows the total fluorescence intensity measured from the images of the HLECs (n = 30 in each group) treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 2, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 24 h. Background fluorescence level was corrected. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, vs control group.

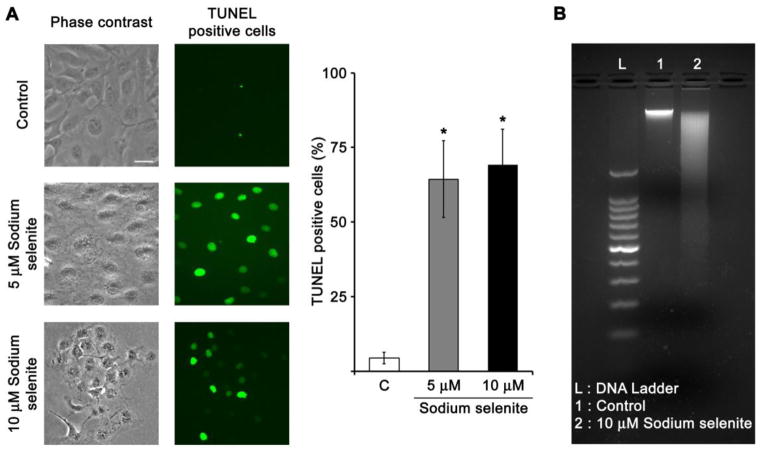

Further, HLECs treated with 5 and 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h showed the TUNEL-positive cells indicating that the cell death was indeed apoptosis (Fig. 5A). In addition, HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h showed significant DNA fragmentation (Fig. 5B), which are consistent with the results of earlier reports [8, 46]. Even though sodium selenite treatment produces significant TUNEL positive HLECs in dose dependent manner, the DNA fragmentation is smear instead of discreet multiple fragments.

Fig. 5.

TUNEL staining and DNA fragmentation assay in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. A. Representative photomicrographs of the TUNEL staining of cultured HLECs treated with 5 and 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h. The scale bar indicates 100 μm. The percentage of TUNEL positive cells was significantly increased compared to that of control HLECs as indicated in the bar diagram. B. DNA fragmentation in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h.

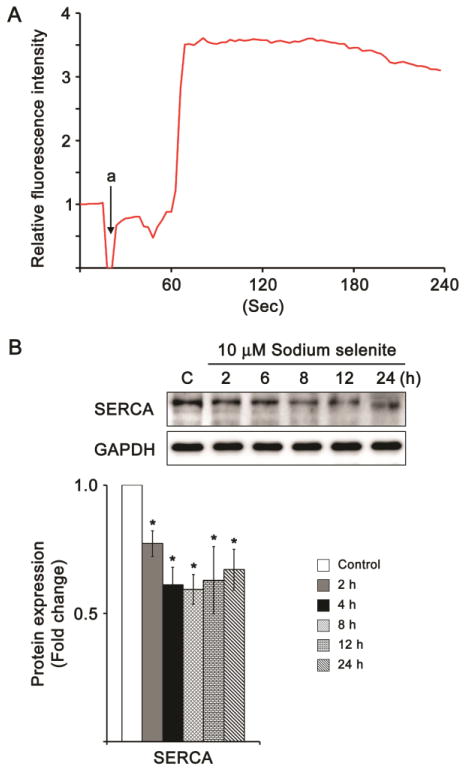

3.4. Selenite releases ER-Ca2+ in HLECs

Next, we studied the selenite-induced ER-Ca2+-release in HLECs by time-lapse confocal laser scanning microscopy, because ER is a major Ca2+-storage organelle in the cell as well as both protein-folding reactions and protein chaperone functions necessitate higher levels of ER-Ca2+. If there is any perturbations in the ER-Ca2+ distribution and regulation, that eventually alters the vital cellular functions leading to apoptosis through terminal UPR [30, 47]. Upon addition of 1 μM sodium selenite, we found spontaneous release of Ca2+ at random locations within HLECs until 50 s (Fig. 6A). After that the Ca2+ release was significantly increased around 62 s and was slowly continue to decrease about 240 s (Fig. 6A). Similarly, we did not find any visible alterations in the selenite-induced spontaneous Ca2+ release by using Ca2+ containing culture medium (data not shown). This result suggests that selenite was eliciting Ca2+ release from the ER. In addition, we found decreased expression levels of SERCA protein, an ER-specific Ca2+ pump, in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h (Fig. 6B) suggesting that selenite treatment induced the variations of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis by releasing ER-Ca2+ as well as decreased the SERCA level in HLECs leading to ER stress activation.

Fig. 6.

Mobilization of Ca2+ from ER and protein expression level of SERCA in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. A. Graph shows the mobilization of Ca2+ from ER, when challenged with 1 μM sodium selenite for about 4 min. In graph, “a” denotes the time at which 1st dose of 1 μM sodium selenite was added to study the ER-Ca2+ release in HLECs. Three independent experiments were performed and all of which were exhibited similar pattern of Ca2+ release from ER when challenged with sodium selenite. B. Protein blot analysis of SERCA in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for various times. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test least significant difference was used to determine the statistical significance: *p < 0.05.

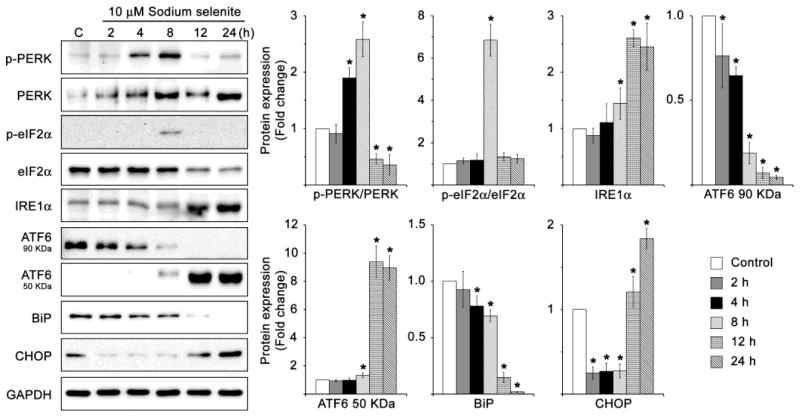

3.5. Selenite induces ER stress and chronic UPR in HLECs

The activation of UPR depends on the concentration and duration of exposure to the ER stressors. But chronic UPR ultimately results in the inability to restore cellular homeostasis, eventually triggering apoptosis [26, 27, 30]. We next examined the sodium selenite mediated induction of ER stress and activation of UPR in HLECs. The expression levels of UPR specific proteins were analyzed in cultured HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for varying time course (Fig. 7). Sodium selenite activates ER stress by phosphorylating PERK by 4–8 h and IRE1α by 12 and 24 h. It is clear that the protein expression of ATF6 (90 kDa) was decreased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite by 2, 4 and 8 h. However, the cleaved active protein expression of ATF6 (50 kDa) was significantly increased, which suggesting that ER stress signaling was apparently activated. Interestingly, the ratios between p-eIF2α/eIF2α were increased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 8 h. By contrast, the protein expression level of BiP was particularly decreased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h. Further, the death factor, CHOP protein expression was significantly decreased at 2–8 h, but it was notably elevated at 12–24 h suggesting the increased cell death (Fig. 7). These results suggest the induction of ER stress and strong activation of UPR within 24 h by 10 μM sodium selenite in HLECs.

Fig. 7.

Activation of ER stress-mediated UPR signaling proteins in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. Immunoblot of p-PERK, PERK, p-elF2α, elF2α, IRE1α, 90 kDa-ATF6, 50 kDa-ATF6, BiP and CHOP in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for various times. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test least significant difference was used to determine the statistical significance: *p < 0.05.

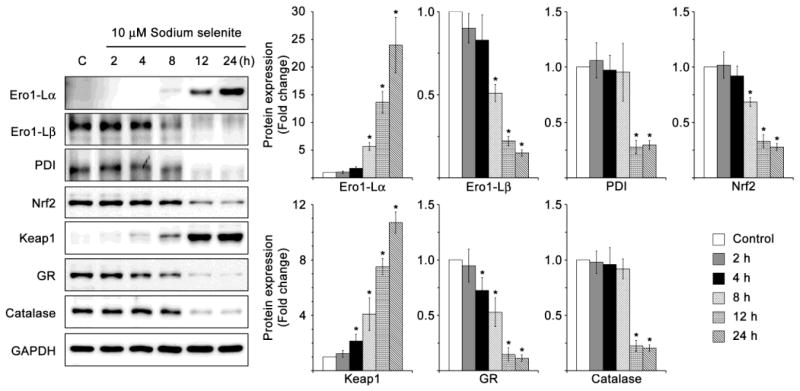

3.6. Selenite alters ER localized oxidative enzymes in HLECs

Then, we investigated the protein expression profiles of ER localized oxidative enzymes such as Ero1-Lα, and Ero1-Lβ, and PDI in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for varying time course. Since, ER is the major site of calcium storage and protein folding with a unique oxidizing-folding machinery, any alterations in the oxidative environment of the ER and also ER Ca2+ cause the production of ER stress-mediated ROS. The ER redox homeostasis is routinely accomplished by a protein relay between ER localized oxidative enzymes Ero1-Lα, and Ero1-Lβ, and PDI [48, 49]. Oxidized Ero1-Lα first transfers its disulfide bond to PDI, which in turn oxidizes substrates, with the backward flow of electrons. The terminal electron acceptor is molecular oxygen. In the UPR, the level of Ero1-Lβ is increased and Ero1-Lα is decreased [50]. Gess and his colleagues also reported that activation of UPR by tunicamycin, a known ER stressor, strongly induced Ero1-Lβ and more moderately Ero1-Lα expression in rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells [51]. In our study, the level of Ero1-Lα was increased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 8, 12 and 24 h compared to that of control HLECs (Fig. 8). Conversely, the protein expression level of Ero1-Lβ was significantly decreased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 8, 12 and 24 h (Fig. 8). But, the protein expression level of PDI was decreased only in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 12 and 24 h (Fig. 8). Since the ROS production in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite was plateau at 8 h and the after that the levels of ROS was declined significantly suggesting that ROS production and ER localized oxidative enzymes have good agreement.

Fig. 8.

Altered protein expressions of ER localized oxidative enzymes and suppression of Nrf2 dependent antioxidant protection in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. Immunoblot of Ero1-Lα, Ero1-Lβ, PDI, Nrf2, Keap1, GR and catalase in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for various times. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test least significant difference was used to determine the statistical significance: *p < 0.05.

3.7. Selenite suppresses the Nrf2 dependent antioxidant protection in HLECs

Next, we studied the protein expression levels of Nrf2 dependent protection proteins in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for different time course. Because, Nrf2 dependent antioxidant protection system plays a crucial role in scavenging ROS generated during various biochemical reactions. We found that the protein expression levels of Nrf2, and Nrf2-target genes, GR, and catalase were significantly decreased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite with time dependent manner when compared to control HLECs (Fig. 8). However, the protein expression level of Keap1, a negative regulator of Nrf2, was significantly increased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h (Fig. 8). These results suggest that Nrf2 dependent antioxidant protection was suppressed upon stress in HLECs.

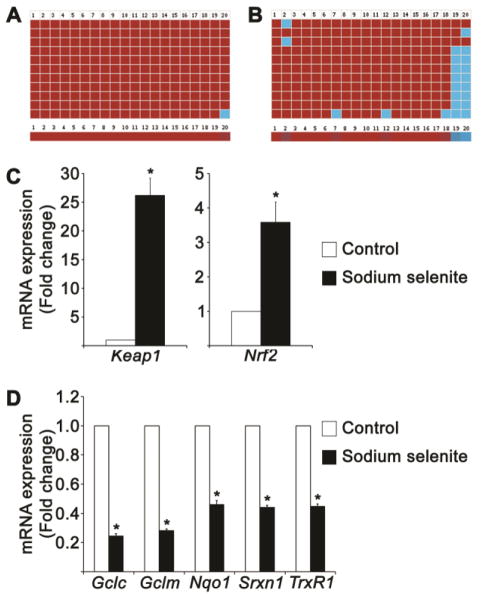

3.8. Selenite induces loss of Keap1 promoter DNA methylation thereby suppressing the Nrf2-target genes in HLECs

We recently reported the promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene in diabetic cataractous lenses as well as in HLECs treated with valproic acid (an antiepileptic drug), tunicamycin (an ER stressor), and 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (an irreversible inhibitor of Dnmts) and this promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene results in overexpression of Keap1 protein [30, 31]. Being a negative regulator of Nrf2, overexpressed Keap1 protein suppresses the Nrf2 protein level. As an outcome, cellular redox balance is altered towards lens oxidation and cataract formation. Hence, we set to study the promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite. We already reported the CpG island status of human Keap1 gene in our previous reports [30, 31]. Human Keap1 gene contains a predominant CpG island located between −460 and +341 with a total number of 68 CpG dinucleotides [31]. We found that the CpG dinucleotides found in the human Keap1 promoter region (20 CpGs between −433 and −96) have predominantly undergone loss of methylation by epigenetic means [30, 31]. Interestingly, bisulfite genomic DNA sequencing studies reveled 10% loss of 5-methylcytosine in the Keap1 promoter of HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h (Fig. 9B) than that of control HLECs (Fig. 9A). It is well-known that the promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene ultimately results in overexpression of Keap1 protein leading to proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 protein, because Keap1 is a negative regulatory protein for Nrf2. To test this, we investigated the mRNA expression profiles of Keap1 and Nrf2 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h by RT-qPCR. Excitingly, we found increased mRNA levels of Keap1 as well as Nrf2 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite (Fig. 9C). These results suggest that sodium selenite-mediated promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene significantly increases the Keap1 transcription in HLECs.

Fig. 9.

Loss of Keap1 promoter DNA methylation and suppression of Nrf2-target genes in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. A. Bisulphite genomic DNA sequencing of control HLECs showing highly methylated CpG dinucleotides. B. Bisulphite genomic DNA sequencing of HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h showing notably demethylated CpG dinucleotides in the region between −433 and −96 of Keap1 promoter. Eleven individual clones of the bisulfite converted DNA sequences of HLECs were analyzed for DNA methylation (contains 20 CpG dinucleotides) of the Keap1 promoter by BISMA software using default filtering threshold settings (http://biochem.jacobs-university.de/BDPC/BISMA/). Each column represents a CpG dinucleotide site and each square indicates a CpG dinucleotide. Red squares represents methylated CpG dinucleotides. Blue squares represent unmethylated CpG dinucleotides, and white-square represents CpG status not determined. The color gradient bar shows that red region contains more methylated CpG dinucleotides and blue region contains more unmethylated CpG dinucleotides. C. RT-qPCR analyses of HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h showing the increased expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 mRNAs. D. RT-qPCR analyses of HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h showing the decreased expression of Nrf2-target genes, such as Gclc, Gclm, Nqo1, Srxn1, and TxrR1 mRNAs. Fold change in the gene expressions were normalized with the internal control, Gapdh. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p<0.05, vs control group.

Next, we studied the mRNA expression profiles of Nrf2-target genes such as, Gclc, Gclm, Nqo1, TrxR1 and Srxn1 in HLECs treated with sodium selenite for 24 h, because the Nrf2 protein is suppressed by higher levels of Keap1 protein leading to suppress the availability of Nrf2 for these transcription of Nrf2-target genes [52–54]. As we expected, the mRNA expression profiles of these Nrf2-target genes were significantly decreased in HLECs treated with sodium selenite for 24 h (Fig. 9D). This results strongly support that sodium selenite suppresses the Nrf2/Keap1 dependent antioxidant protection in HLECs.

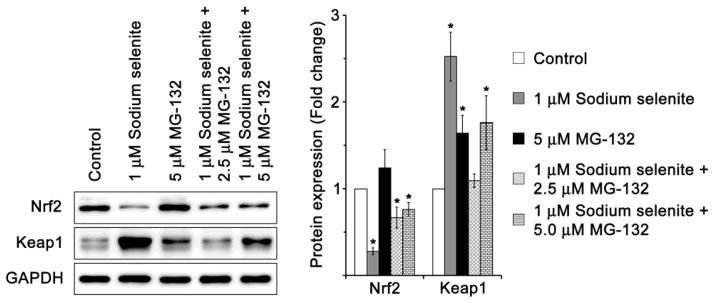

3.9. Selenite extends proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 protein in HLECs

From the Fig. 9C, we can understand that the mRNA expression profile of Nrf2 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite also increased significantly when compared to control HLECs. However, the protein expression profile of Nrf2 was decreased significantly in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite also increased significantly when compared to control HLECs (Fig. 8). We expect that this discrepancy is due to proteasomal degradation (ERAD) of Nrf2. To conform this, HLECs were pretreated with 2.5 and 5 μM MG-132, an inhibitor of proteasome protease, for 4 h. Then, the pretreated HLECs were treated with 1 μM sodium selenite for another 24 h. The protein expression profile revealed that sodium selenite treatment to HLECs augments significant proteasomal degradation of Nrf2, but not the Keap1 protein (Fig. 10). However, MG-132 pretreated HLECs then cultured with 1 μM sodium selenite for 24 h revealed significant increase in the protein expressions of Nrf2 and Keap1 than that of HLECs treated with 1 μM sodium selenite alone. These results further suggest that sodium selenite augments degradation of Nrf2 and Keap1 proteins through activation of proteasomal degradation. However, it is unclear to us about the significant reduction in the Keap1 protein expression after MG-132 treatment, which requires further detailed study. Conversely, HLECs treated with methylglyoxal showed significantly increased expression of Keap1 protein after pretreatment with MG-132 [55].

Fig. 10.

Prevention of sodium selenite-mediated protein degradation in HLECs by MG-132, a proteasome protease inhibitor. Immunoblot of Nrf2, and Keap1 in HLECs precultured with 2.5 and 5 μM MG-132 for 4 h, followed by a washout in regular medium, with or without 1 μM sodium selenite for 24 h. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test least significant difference was used to determine the statistical significance: *p < 0.05.

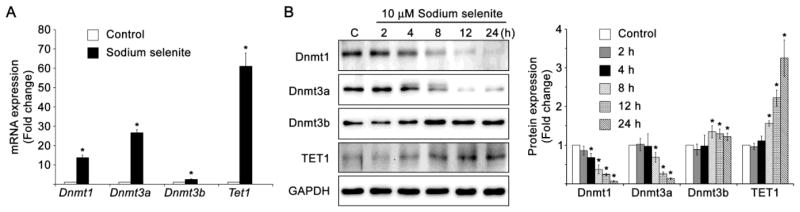

3.10. Selenite modifies DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs

Next, we analyzed the protein expression profiles of active and passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h, since sodium selenite induces the promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene in HLECs. The RT-qPCR studies reveal the significantly increased expressions of mRNAs of passive DNA demethylation pathways enzymes such as, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b, as well as active DNA demethylation pathway enzyme, Tet1 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h (Fig. 11A). Further, we found that the protein expression profiles of passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes such as Dnmt1, and Dnmt3a were significantly decreased (rather Dnmt3b was increased) in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for variable times than that of control HLECs (Fig. 11B). Further, the protein expression of active DNA demethylation enzyme, TET1 was significantly increased in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 8, 12 and 24 h when compare to control HLECs (Fig. 11B). These results suggest the involvement DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in the promoter DNA demethylation of Keap1 gene in HLECs treated to 10 μM sodium selenite.

Fig. 11.

Altered expressions of passive and active DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs treated with sodium selenite. A. RT-qPCR of passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes, such as Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b, and active DNA demethylation pathway enzyme, Tet1 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 h. Fold change in the gene expressions were normalized with the internal control, Gapdh. B. Immunoblot of passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b, and active DNA demethylation pathway enzyme, TET1 in HLECs treated with 10 μM sodium selenite for 24 oh. GAPDH was probed as a loading control. The data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA followed by post hoc test least significant difference was used to determine the statistical significance: *p < 0.05.

4. Discussion

The selenite-induced cataract formed in young suckling rats is one of the most commonly used animal models for nuclear cataract [8]. The single subcutaneous injection of sodium selenite into young suckling rats results in cortical opacities and nuclear cataract within 4–6 days [56]. This model holds various advantages like early cataract formation, convenience, and reproducibility. Further, selenite-induced cortical cataracts principally involved in protein degradation, liquefaction, and abnormal fibrogenesis.

Selenite potentially oxidizes various cellular components, principally all proteins by forming a covalent linkage with protein sulfhydryl groups [8]. There are several reports indicating the loss of thiol groups in the LECs exposed to sodium selenite [57]. Sodium selenite also reported to change the conformational structure by oxidizing –SH group in the cysteine residues of Bax, tubulin and AE1 proteins to form a disulfide bridges (protein-S-Se-S-protein) in the ER leading to ER stress and apoptosis [20–22]. Our results also consistent with these reports and infer the misfolded proteins-mediated ER stress. These results further suggest that selenite can interact with membrane and secretory lens proteins leading to protein conformational change, which is a crucial factor for severe ER stress.

Recent reports have connected the ER stress with ROS overproduction through oxidative protein folding [49, 50, 58]. Further, UPR also mainly involved in the regulation of ER components coupled in ROS production [59]. Similarly, Wang and his colleagues recently reported the influence of Sigma-1 receptor, an ER stress regulator, against oxidative damage through suppression of the ER stress responses in the human lens [60]. Continuous supply of disulfide bonds is an essential component of protein folding process and is introduced into the client proteins by the enzyme, Ero1. Ero1 generally donates a disulfide bond to PDI and transfers the electrons from PDI to molecular oxygen leading to ROS production [61]. Due to its toxicity, sodium selenite stimulates exaggerated production of ROS prior to death of LECs. Our results showed that Ero1-Lα was significantly increased and PDI and Ero1-Lβ was significantly decreased in HLECs treated with sodium selenite for 24 h. It is well-known that ER stress mediated apoptosis can be triggered by a robust ER stress stimulus or through the combination of low level of ER stress with prolonged time duration. Li and his colleagues also reported that increased Ero1-Lα is responsible for triggering CHOP-mediated apoptosis [62]. These findings differ from other cataractogenic stressors such as valproic acid [30], low glucose and hypoxia [26], homocysteine [26], calcium ionophore (A23178), tunicamycin [28], and galactose [29]. These stressors maintain higher levels of PDI, and Ero1-Lβ in HLECs, with decreased Ero1-Lα. Further loss of PDI also inhibits the ROS production relay during oxidative protein folding [63]. These observations suggest that selenite did not produce the ROS by PDI/Ero1-Lβ pathway in HLECs but produce from mitochondrial dysfunction as reported [6]. Other reports also supported the notion about superoxide production through the mitochondria-dependent pathway in human prostate cancer cells [64] as well as in A549 human lung carcinoma cells treated with selenite [65]. Further the lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected suckling rats by day 2 appeared to produce higher levels of ROS in LECs as well as the superficial lens fiber cells. Also, immature lens fiber cells are relatively abundant in the lenses of 16-days old rats and these lens fiber cells retain the cellular organelles such as mitochondria, and ER, which could have release the ROS upon selenite exposure. This induces significant damages in the cortical region of the lens fiber cells leading to lens liquefaction.

In addition with ER oxidizing environment, high ER-Ca2+ is critical for proper protein folding. Depletion of ER-Ca2+ eventually results in protein misfolding and decreases chaperone function thereby activating ER stress [66]. SERCA is a major regulator of ER stress, which actively pumps the cytosolic Ca2+ into the ER store. It is reported that thapsigargin, an inhibitor of SERCA, blocked the cytosolic Ca2+ uptake and created a chaotic environment in the ER lumen leading to ER stress with subsequent activation of UPR [67, 68]. Similarly, the Ca2+ ionophore, A23187, also reported to disrupt ER-Ca2+ homeostasis thereby triggering severe ER stress [69, 70]. Likewise, arsenic trioxide also induces the ER stress by disturbing calcium signaling thereby stimulating apoptosis in HLECs [71]. The decreased protein expression of SERCA in HLECs treated with sodium selenite suggests that the Ca2+ released from ER remains in the cytosol and activates m-calpain.

Activated m-calpain, a Ca2+-dependent cysteine protease, in turn translocated from cytosol to ER to cleave off the CARD pro-domain of caspase-12 leading to activation of caspase-12, caspase-9, caspase-3, and caspase-1 [25, 72, 73]. There are several reports that provide convincing evidence that sodium selenite activates m-calpain activity in the lenses of human as well as other animals [74]. Further, activated m-calpain and caspases are reported to cleave off lens crystallin proteins [7, 17, 46] leading to cataract formation [75]. Similarly, Nrf2 is also one of the substrates for caspase-3, because Nrf2 has two caspase-3 cleavage consensus sites at D208 and D366 of its aminoacid sequence [26, 76]. This cleavage of Nrf2 results in 30 kDa and 50kDa peptides and are detected in HLECs treated with homocysteine, a well-known ER stressor [26]. Thus elevated level of cytosolic Ca2+ activates multiple dysfunctional machineries by sodium selenite-mediated ER stress.

Selenite also known to accelerate loss of various cytoskeletal proteins such as actin, tubulin/vimentin, and spectrin, as well as unidentified nuclear proteins of 49, 60 and 90 kDa and these cytoskeletal proteins are mainly involved in the stabilization of transparent cell structure [8, 15]. Thus, degradation of cytoskeletal proteins and various crystallin proteins are the crucial factors during early stages of selenite-induced nuclear cataract formation. Further, clearance of sodium selenite by the injected animals leads to normal LECs growing over the damaged lens fiber cells after 9–10 days.

Further, it is well documented that LECs are known to induce ER stress by various cataractogenic stressors. However, there is no information about ER stress activation in the lens fiber cells, i.e. in immature lens fiber cells which are losing cellular organelles or in differentiating lens fiber cells. We found significant level of ROS production in the cortical immature lens fiber cells in which cortical cataract to be appeared due to extensive liquefaction, protein degradation, and abnormal fibrogenesis [77]. Also, selenite is cataractogenic when only administered to young rats [8], because large amount of immature lens fiber cells are present in the cortical region at this time. Interestingly, Firtina and his colleagues reported that the ER stress associated proteins such as BiP, PDI, X-box binding protein 1, ATF4, ATF6, and p-PERK are expressed during normal lens fiber cell differentiation [78]. In addition, we also reported the expression of Ero1-lβ in the cortical lens fiber cells of age-related cataractous lenses from a 57-year-old individual [26]. Further, the EthD staining (cell death staining) of lenses enucleated from sodium selenite injected rats by day 2 and day 3 revealed disturbed lens fiber cells or artefact of premature lens fiber cells that has increased autofluorescence in the red channel. Similar results were found in rat lenses treated with various ER stressors, such as homocysteine [26], low glucose with hypoxic conditions [26], galactose [29], tunicamycin, and calcium ionophore [28]. But we couldn’t found this pattern of staining in cultured HLECs and control rats lenses. These results suggest that differentiating immature lens fiber cells are highly susceptible to the ER stressors including sodium selenite leading to DNA degeneration in lens fiber cells. However, this requires further detailed studies.

Sodium selenite treatment to HLECs results in significantly increased mRNA expressions of Nrf2, Keap1, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Tet1. Ma and his colleagues also reported the overexpression of m-calpain and calpastatin mRNA in selenite-induced cataractous lenses [79]. The possible notions for the elevated mRNA expression levels are formation of stress granules and loss of promoter DNA methylation. Stress granules are large cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein complexes that are accumulated when cells are exposed to stress. Upon ER stress, p-PERK activates the phosphorylation of eIF2α, which is essential for stress granules formation [80]. Stress granules promote the survival of the stressed cells by contributing to the reprogramming of protein translations as well as by blocking pro-apoptotic signaling cascades [81]. This translational repression results in storing mRNAs into the stress granules [80]. Some RNAs are remained stored in the granules while some RNAs are degraded and some others are returned to the cytoplasm for translation [82]. It is possible that Keap1 and Nrf2 mRNAs are stored and some of them are in part degraded by the selection of the stress granules.

Further, Fujimura and his colleagues proposed that selenite-induced stress granules formations differ from canonical mammalian stress granules in respect of their morphology, composition, and mechanism of assembly [81]. Their assembly is induced primarily by eTF4E-binding protein 1-mediated inhibition of translation initiation, which is reinforced by concurrent phosphorylation of eIF2α. Further, selenite-induced stress granules lack various classical stress granules components, including proteins involved in prosurvival functions of canonical stress granules [81]. Our results also consistent with these findings and provide an insights how does selenite stress work during cataractogenesis. In addition, the mutations in the Tudor domain RNA binding protein, one of the component of stress granules is reported to induce glaucoma and cataract formation suggesting the vital role of stress granules in cataract formation during lens development [83]. Due to lack of methodology to isolate these stress granules, we could not quantify the mRNAs of Nrf2, Keap1, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Tet1 stored in the stress granules.

Selenite also induces general DNA degradation as described in various reports [7, 84], and the fragmented DNA significantly suppresses the transcription of various genes. However, we don’t know whether Tet1 and Keap1 genes are degraded in HLECs shortly after treated with sodium selenite. Though the expression levels of these mRNAs are regulated by multiple factors as well as multiple levels, we are anticipating to investigate these aspects in the near future.

Additionally, loss of DNA methylation in the promoter region of a gene activates its transcription whereas DNA methylation inhibits the gene transcription. The loss of DNA methylation in the Keap1 promoter of HLECs treated with sodium selenite activates the transcription of Keap1 and results in significantly higher levels of its mRNA and protein. Sodium selenite also reported to induce hypomethylation in the hemoglobin gene in Friend erythroleukemic cells [85]. Xiang and his colleagues also reported that sodium selenite treatment epigenetically modulate DNA and histones to activate methylation-silenced genes in prostate cancer cells [86]. These results indicate that transcriptional activation by the loss of the DNA methylation in part play a significant role in the overexpression of their mRNAs. In addition, sodium selenite reduces the levels of Nrf2 thereby suppresses the transcripts of Nrf2-target genes in HLECs. This suppression of the Nrf2-target genes was much greater than we expected.

In summary, our studies indicate the induction of ER stress mediated activation of UPR, release of ER-Ca2+, overproduction of ROS and cell death, and loss of Keap1 promoter DNA methylation through the altered expressions of active and passive DNA demethylation pathway enzymes in HLECs treated with sodium selenite for 24 h. These sequential events can be responsible for the failure of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant protection in HLECs thereby the lens redox system is altered towards lens oxidation leading to cataract formation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Selenite induces cataract in suckling rats through ROS production and cell death

Selenite induces ER-Ca2+ release in human lens epithelial cells (HLECs)

Selenite induces ER stress and unfolded protein response in HLECs

Selenite suppresses Nrf2/Keap1 dependent antioxidant protection in HLECs

Selenite induces loss of promoter DNA methylation in human Keap1 gene

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the RPB and EY0180172. We thank Janice A. Taylor and James R. Talaska of the Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center for providing assistance with confocal microscopy and the Nebraska Research Initiative and the Eppley Cancer Center for their support of the Core Facility, and the UNMC DNA Sequencing Core Facility (supported by P20 RR016469 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources) for sequencing analysis.

Abbreviations

- AE1

anion exchanger 1

- ATF6

activating transcription factor 6

- BiP

immunoglobulin heavy-chain binding protein

- CHOP

C/EBP-homologous protein

- Dnmt

DNA methyltransferase

- eIF2α

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- Ero1

ER oxidoreductin 1

- EthD

ethidium homodimer-III

- Gclc

glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit

- Gclm

glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit

- GR

glutathione reductase

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- H2-DCFH-DA

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- HLECs

human lens epithelial cells

- IRE1α

inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- Nqo1

quinone reductase

- Nrf2

nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- PERK

PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-qPCR

real-time quantitative PCR

- SERCA

sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium-transporting ATPase

- Srxn1

sulfiredoxin-1

- TET1

ten-eleven translocation 1 protein

- TrxR1

thioredoxin reductase 1

- UPR

unfolded protein response

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Periyasamy Palsamy, Email: palsamy.periyasamy@unmc.edu.

Toshimichi Shinohara, Email: tshinohara@unmc.edu.

References

- 1.Petrash JM. Aging and age-related diseases of the ocular lens and vitreous body. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54 doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12940. ORSF54-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu H, Zhang H, Li P, Gao T, Lin J, Yang J, Wu Y, Ye J. Association between dietary carbohydrate intake and dietary glycemic index and risk of age-related cataract: A meta-analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014 doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13695. IOVS-13-13695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selenius M, Rundlof AK, Olm E, Fernandes AP, Bjornstedt M. Selenium and the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase in the prevention, treatment and diagnostics of cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:867–880. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husbeck B, Nonn L, Peehl DM, Knox SJ. Tumor-selective killing by selenite in patient-matched pairs of normal and malignant prostate cells. Prostate. 2006;66:218–225. doi: 10.1002/pros.20337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selvaraj V, Tomblin J, Yeager Armistead M, Murray E. Selenium (sodium selenite) causes cytotoxicity and apoptotic mediated cell death in PLHC-1 fish cell line through DNA and mitochondrial membrane potential damage. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;87:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan L, Han B, Li Z, Hua F, Huang F, Wei W, Yang Y, Xu C. Sodium selenite induces apoptosis by ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in human acute promyelocytic leukemia NB4 cells. Apoptosis. 2009;14:218–225. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shearer TR, David LL, Anderson RS. Selenite cataract: a review. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6:289–300. doi: 10.3109/02713688709025181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shearer TR, Ma H, Fukiage C, Azuma M. Selenite nuclear cataract: review of the model. Mol Vis. 1997;3:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Bunce GE, Hess JL. Selenite and Ca2+ homeostasis in the rat lens: effect on Ca-ATPase and passive Ca2+ transport. Curr Eye Res. 1993;12:213–218. doi: 10.3109/02713689308999466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Hess JL, Bunce GE. Calcium efflux in rat lens: Na/Ca-exchange related to cataract induced by selenite. Curr Eye Res. 1992;11:625–632. doi: 10.3109/02713689209000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess JL, Mitton KP, Bunce GE. Precataractous changes affect lens transparency in the selenite cataract. Ophthalmic Res. 1996;28(Suppl 2):45–53. doi: 10.1159/000267956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Hess JL, Bunce GE. Deferoxamine effect on selenite-induced cataract formation in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:2511–2519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunce GE, Hess JL. Biochemical changes associated with selenite-induced cataract in the rat. Exp Eye Res. 1981;33:505–514. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(81)80125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang LL, Hess JL, Bunce GE. DNA damage, repair, and replication in selenite-induced cataract in rat lens. Curr Eye Res. 1990;9:1041–1050. doi: 10.3109/02713689008997578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushima H, David LL, Hiraoka T, Clark JI. Loss of cytoskeletal proteins and lens cell opacification in the selenite cataract model. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:387–395. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelley MJ, David LL, Iwasaki N, Wright J, Shearer TR. alpha-Crystallin chaperone activity is reduced by calpain II in vitro and in selenite cataract. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18844–18849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shearer TR, David LL, Anderson RS, Azuma M. Review of selenite cataract. Curr Eye Res. 1992;11:357–369. doi: 10.3109/02713689209001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark JI, Steele JE. Phase-separation inhibitors and prevention of selenite cataract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1720–1724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitton KP, Hess JL, Bunce GE. Causes of decreased phase transition temperature in selenite cataract model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:914–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang F, Nie C, Yang Y, Yue W, Ren Y, Shang Y, Wang X, Jin H, Xu C, Chen Q. Selenite induces redox-dependent Bax activation and apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:1186–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang FY, Fen C, Tu YP. Se-mediated domain-domain communication in band 3 of human erythrocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;55:279–295. doi: 10.1007/BF02785286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leynadier D, Peyrot V, Codaccioni F, Briand C. Selenium: inhibition of microtubule formation and interaction with tubulin. Chem Biol Interact. 1991;79:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90055-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozutsumi Y, Segal M, Normington K, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. The presence of malfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum signals the induction of glucose-regulated proteins. Nature. 1988;332:462–464. doi: 10.1038/332462a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schroder M. The unfolded protein response. Mol Biotechnol. 2006;34:279–290. doi: 10.1385/MB:34:2:279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szegezdi E, Fitzgerald U, Samali A. Caspase-12 and ER-stress-mediated apoptosis: the story so far. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1010:186–194. doi: 10.1196/annals.1299.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elanchezhian R, Palsamy P, Madson CJ, Lynch DW, Shinohara T. Age-related cataracts: homocysteine coupled endoplasmic reticulum stress and suppression of Nrf2-dependent antioxidant protection. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;200:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elanchezhian R, Palsamy P, Madson CJ, Mulhern ML, Lynch DW, Troia AM, Usukura J, Shinohara T. Low glucose under hypoxic conditions induces unfolded protein response and produces reactive oxygen species in lens epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e301. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ikesugi K, Yamamoto R, Mulhern ML, Shinohara T. Role of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in cataract formation. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulhern ML, Madson CJ, Danford A, Ikesugi K, Kador PF, Shinohara T. The unfolded protein response in lens epithelial cells from galactosemic rat lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3951–3959. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palsamy P, Bidasee KR, Shinohara T. Valproic acid suppresses Nrf2/Keap1 dependent antioxidant protection through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and Keap1 promoter DNA demethylation in human lens epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palsamy P, Ayaki M, Elanchezhian R, Shinohara T. Promoter demethylation of Keap1 gene in human diabetic cataractous lenses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:11632–11639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Santos CX, Tanaka LY, Wosniak J, Laurindo FR. Mechanisms and implications of reactive oxygen species generation during the unfolded protein response: roles of endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductases, mitochondrial electron transport, and NADPH oxidase. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2409–2427. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cullinan SB, Diehl JA. PERK-dependent activation of Nrf2 contributes to redox homeostasis and cell survival following endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20108–20117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cullinan SB, Diehl JA. Coordination of ER and oxidative stress signaling: the PERK/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7198–7209. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayes JD, McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.So HS, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Park SY, Park C, Kim YH, Kim JK, Lee KM, Kim KS, Chung SY, Jang WC, Moon SK, Chung HT, Park RK. Flunarizine induces Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activation of heme oxygenase-1 in protection of auditory cells from cisplatin. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1763–1775. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Smith AJ, Lott MC, Bao Y, Bowater RP, Reddan JR, Wormstone IM. Sulforaphane can protect lens cells against oxidative stress: implications for cataract prevention. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:5236–5248. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abramoff MD, Magelhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao CH, Wehrens XH, Wyatt TA, Parbhu S, Rozanski GJ, Patel KP, Bidasee KR. Exercise training during diabetes attenuates cardiac ryanodine receptor dysregulation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;106:1280–1292. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91280.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rohde C, Zhang Y, Reinhardt R, Jeltsch A. BISMA--fast and accurate bisulfite sequencing data analysis of individual clones from unique and repetitive sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:230. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higa A, Chevet E. Redox signaling loops in the unfolded protein response. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1548–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Yang X, Zhang Z, Xu H. Both calcium and ROS as common signals mediate Na(2)SeO(3)-induced apoptosis in SW480 human colonic carcinoma cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2003;97:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(03)00284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aaltonen P, Amory JK, Anderson RA, Behre HM, Bialy G, Blithe D, Bone W, Bremner WJ, Colvard D, Cooper TG, Elliesen J, Gabelnick HL, Gu YQ, Handelsman DJ, Johansson EA, Kersemaekers W, Liu P, MacKay T, Matlin S, Mbizvo M, McLachlan RI, Meriggiola MC, Mletzko S, Mommers E, Muermans H, Nieschlag E, Odlind V, Page ST, Radlmaier A, Sitruk-Ware R, Swerdloff R, Wang C, Wu F, Zitzmann M. 10th Summit Meeting consensus: recommendations for regulatory approval for hormonal male contraception. J Androl. 2007;28:362–363. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azuma M, Fukiage C, David LL, Shearer TR. Activation of calpain in lens: a review and proposed mechanism. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:529–538. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hetz C, Chevet E, Harding HP. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:703–719. doi: 10.1038/nrd3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pagani M, Fabbri M, Benedetti C, Fassio A, Pilati S, Bulleid NJ, Cabibbo A, Sitia R. Endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1-lbeta (ERO1-Lbeta), a human gene induced in the course of the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23685–23692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003061200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tu BP, Weissman JS. The FAD- and O(2)-dependent reaction cycle of Ero1-mediated oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell. 2002;10:983–994. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tu BP, Weissman JS. Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:341–346. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gess B, Hofbauer KH, Wenger RH, Lohaus C, Meyer HE, Kurtz A. The cellular oxygen tension regulates expression of the endoplasmic oxidoreductase ERO1-Lalpha. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2228–2235. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hirotsu Y, Katsuoka F, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Nishida Y, Nakayama K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M. Nrf2-MafG heterodimers contribute globally to antioxidant and metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10228–10239. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muller M, Banning A, Brigelius-Flohe R, Kipp A. Nrf2 target genes are induced under marginal selenium-deficiency. Genes Nutr. 2010;5:297–307. doi: 10.1007/s12263-010-0168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs L, Gautam T, Jimenez R, Losonczy G, Zhang C, Ballabh P, Recchia FA, Wilkerson DC, Sonntag WE, Pearson K, de Cabo R, Csiszar A. Adaptive induction of NF-E2-related factor-2-driven antioxidant genes in endothelial cells in response to hyperglycemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H1133–1140. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00402.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palsamy P, Bidasee KR, Ayaki M, Augusteyn RC, Chan JY, Shinohara T. Methylglyoxal induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and DNA demethylation in the Keap1 promoter of human lens epithelial cells and age-related cataracts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72C:134–148. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ostadalova I, Babicky A, Obenberger J. Cataract induced by administration of a single dose of sodium selenite to suckling rats. Experientia. 1978;34:222–223. doi: 10.1007/BF01944690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hightower KR, McCready JP. Effect of selenite on epithelium of cultured rabbit lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:406–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Novoa I, Lu PD, Calfon M, Sadri N, Yun C, Popko B, Paules R, Stojdl DF, Bell JC, Hettmann T, Leiden JM, Ron D. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell. 2003;11:619–633. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Eldred JA, Sidaway P, Sanderson J, Smith AJ, Bowater RP, Reddan JR, Wormstone IM. Sigma 1 receptor stimulation protects against oxidative damage through suppression of the ER stress responses in the human lens. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benham AM, van Lith M, Sitia R, Braakman I. Ero1-PDI interactions, the response to redox flux and the implications for disulfide bond formation in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20110403. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li G, Mongillo M, Chin KT, Harding H, Ron D, Marks AR, Tabas I. Role of ERO1-alpha-mediated stimulation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor activity in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:783–792. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arap MA, Lahdenranta J, Mintz PJ, Hajitou A, Sarkis AS, Arap W, Pasqualini R. Cell surface expression of the stress response chaperone GRP78 enables tumor targeting by circulating ligands. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:275–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiang N, Zhao R, Zhong W. Sodium selenite induces apoptosis by generation of superoxide via the mitochondrial-dependent pathway in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;63:351–362. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park SH, Kim JH, Chi GY, Kim GY, Chang YC, Moon SK, Nam SW, Kim WJ, Yoo YH, Choi YH. Induction of apoptosis and autophagy by sodium selenite in A549 human lung carcinoma cells through generation of reactive oxygen species. Toxicol Lett. 2012;212:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mekahli D, Bultynck G, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Missiaen L. Endoplasmic-reticulum calcium depletion and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lytton J, Westlin M, Hanley MR. Thapsigargin inhibits the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum Ca-ATPase family of calcium pumps. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17067–17071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas GR, Sanderson J, Duncan G. Thapsigargin inhibits a potassium conductance and stimulates calcium influx in the intact rat lens. J Physiol. 1999;516(Pt 1):191–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.191ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duncan G, Wormstone IM. Calcium cell signalling and cataract: role of the endoplasmic reticulum. Eye. 1999;13(Pt 3b):480–483. doi: 10.1038/eye.1999.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vangheluwe P, Raeymaekers L, Dode L, Wuytack F. Modulating sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase 2 (SERCA2) activity: cell biological implications. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang H, Duncan G, Wang L, Liu P, Cui H, Reddan JR, Yang BF, Wormstone IM. Arsenic trioxide initiates ER stress responses, perturbs calcium signalling and promotes apoptosis in human lens epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:825–835. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morishima N, Nakanishi K, Takenouchi H, Shibata T, Yasuhiko Y. An endoplasmic reticulum stress-specific caspase cascade in apoptosis. Cytochrome c-independent activation of caspase-9 by caspase-12. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34287–34294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rao RV, Hermel E, Castro-Obregon S, del Rio G, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Mechanism of caspase activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33869–33874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.David LL, Shearer TR. Role of proteolysis in lenses: a review. Lens Eye Toxic Res. 1989;6:725–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shih M, David LL, Lampi KJ, Ma H, Fukiage C, Azuma M, Shearer TR. Proteolysis by m-calpain enhances in vitro light scattering by crystallins from human and bovine lenses. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:458–469. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.6.458.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ohtsubo T, Kamada S, Mikami T, Murakami H, Tsujimoto Y. Identification of NRF2, a member of the NF-E2 family of transcription factors, as a substrate for caspase-3(-like) proteases. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:865–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson RS, Trune DR, Shearer TR. Histologic changes in selenite cortical cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1418–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Firtina Z, Duncan MK. Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) is activated during normal lens development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2011;11:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma H, Shih M, Throneberg DB, David LL, Shearer TR. Changes in calpain II mRNA in young rat lens during maturation and cataract formation. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:437–445. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fujimura K, Sasaki AT, Anderson P. Selenite targets eIF4E-binding protein-1 to inhibit translation initiation and induce the assembly of non-canonical stress granules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8099–8110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]